Abstract

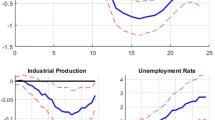

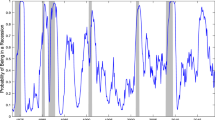

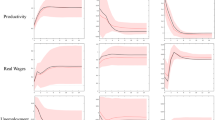

This paper examines how structural oil price shocks affect the US unemployment at the aggregate level and across the duration of unemployment spells. I find that adverse oil supply shocks produce a recessionary effect by significantly increasing the aggregate unemployment measures and the number of persons unemployed for 5 weeks or more. Aggregate demand shocks increase unemployment with a lag of a year and show a short-run fall in the number of unemployed between 5 and 26 weeks. While precautionary demand shocks have a muted effect on the unemployment rate, they temporarily raise short-term spells of unemployment but drop the number of unemployed between 5 and 26 weeks. Additionally, aggregate demand shocks are essential in explaining the duration of unemployment during the oil price surge of 2003–2008, the Great Recession, and the 2010–2014 period of stable oil prices. The findings also reflect that supply-driven shocks played a more important role in long-term unemployment during the 1970s–1980s period, whereas demand-driven shocks dominated the labor market during later periods of the 2000s.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Kilian (2009) denotes those shifts in the demand for crude oil associated with unexpected fluctuations in global real economic activity as “aggregate demand shocks.”

The monthly index is now published by the FRED at: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/IGREA

For a detailed analysis of the Kilian index advantages over other measures and some possible limitations, see Kilian and Zhou (2018), Kilian (2019), Funashima (2020), Nonejad (2020), and Kilian (2022a). Funashima (2020), for instance, shows that the Kilian index is a leading indicator for the world industrial production index.

Throughout the text and figures “aggregate unemployment” refers to “total number of unemployed”

I de-trend the \(U_{<5}\) and \(U_{>26}\) measures.

Finding opposite responses for different unemployment spells is not surprising. In times of economic crisis, unemployed take longer to find a new job and thus move along the spell ladder from shorter to longer spells.

As a robustness check, I reconsider the transformation of the real price of crude oil from log difference to log deviation from the sample mean as in Kilian (2009). I also experiment expressing the duration variables as a fraction of the total number of unemployed persons rather than the log difference of the number of persons unemployed for a certain duration. I find that all the results are robust to the transformation choices.

Following the literature in the global oil market, I include 24 monthly lags which is appropriate to remove serial correlation by giving a sufficient delay in the response of the economy to structural shocks in the crude oil market (see, among others, Kilian 2009; Kilian and Lütkepohl 2017). I also estimate the model using 12 monthly lags and find that the results are robust to this change in lag length.

I specify the block-recursive VAR model with the global oil market block ordered first and the domestic variable on unemployment ordered last.

Oil-specific demand shocks, also referred to as precautionary demand shocks, represent changes in oil demand, as a precaution, due to concerns about future oil supply availability.

To preserve space, I only include the responses of the real price of oil and the unemployment measures. The responses of world oil production and real economic activity are available upon request.

Note the methodological differences in both studies in terms of the choice of data and the questions tackled (global versus the USA).

To preserve space, I only include the responses of \(U_{<5}\) and \(U_{>26}\). The responses of the unemployment rate, aggregate unemployment duration, and unemployment spells of \(U_{5-14}\) and \(U_{15-26}\) are available upon request.

In this paper, I use “OECD index” and “World Industrial Production Index (WIP)” interchangeably.

The index is available at: https://sites.google.com/site/cjsbaumeister/datasets.

Funashima (2020) and Herrera and Rangaraju (2020) use log-linearly detrended series of WIP when comparing with the Kilian’s index. I use growth rate given that all the variables in the model are included in growth rates. I also run the model using the log-linearly detrended WIP, the results are unaffected by this change.

Alternatively, one can estimate the oil market shocks using the global oil market model first developed by Kilian and Murphy (2014). Since both models generate close results after conditioning on a range of prior distribution supported by micro econometric verification (see, Herrera and Rangaraju 2020, I use the off-the-shelf structural oil market shocks from Baumeister and Hamilton 2019.

The time series for the oil market structural shocks are available from Baumeister’s website starting from 1975.2 and updated regularly at: https://sites.google.com/site/cjsbaumeister/research.

See Känzig (2021) for a detailed construction of the oil supply surprise series and identification of oil supply news shock.

OSNS is available at: https://github.com/dkaenzig/oilsupplynews.

The series is available at Güntner’s website from 1973.1 onward at: https://sites.google.com/site/econjochen/research.

References

Alsalman Z (2021) Does the source of oil supply shock matter in explaining the behavior of us consumer spending and sentiment? Empir Econ 61:1491–1518

Alsalman ZN, Karaki MB (2019) Oil prices and personal consumption expenditures: does the source of the shock matter? Oxford Bull Econ Stat 81:250–270

Anderson ST, Kellogg R, Salant SW (2018) Hotelling under pressure. J Polit Econ 126:984–1026

Baumeister C, Hamilton JD (2019) Structural interpretation of vector autoregressions with incomplete identification: revisiting the role of oil supply and demand shocks. Am Econ Rev 109:1873–1910

Baumeister C, Kilian L (2014) What central bankers need to know about forecasting oil prices. Int Econ Rev 55:869–889

Baumeister C, Kilian L (2016) Lower oil prices and the us economy: is this time different? Brook Pap Econ Act 2016:287–357

Baumeister C, Kilian L (2016) Understanding the decline in the price of oil since June 2014. J Assoc Environ Resour Econ 3:131–158

Baumeister C, Kilian L, Zhou X (2018) Is the discretionary income effect of oil price shocks a hoax?, Energy J, 39

Bell DN, Blanchflower DG (2018) The lack of wage growth and the falling nairu. Natl Inst Econ Rev 245:R40–R55

Belz S, Wessel D, Yellen J (2020) What’s (not) up with inflation. The Brookings Institution, Washington, DC

Borenstein S, Kellogg R (2012) The incidence of an oil glut: Who benefits from cheap crude oil in the midwest?, Tech Rep, National Bureau of Economic Research

Caffarra C (1990) The role and behaviour of oil inventories, Oxford Institute for Energy Studies

Caldara D, Cavallo M, Iacoviello M (2019) Oil price elasticities and oil price fluctuations. J Monet Econ 103:1–20

Cashin P, Mohaddes K, Raissi M, Raissi M (2014) The differential effects of oil demand and supply shocks on the global economy. Energy Econ 44:113–134

Davis SJ, Haltiwanger J (2001) Sectoral job creation and destruction responses to oil price changes. J Monet Econ 48:465–512

Edelstein P, Kilian L (2009) How sensitive are consumer expenditures to retail energy prices? J Monet Econ 56:766–779

Feng S, Hu Y (2013) Misclassification errors and the underestimation of the us unemployment rate. Am Econ Rev 103:1054–70

Funashima Y (2020) Global economic activity indexes revisited. Econ Lett 193:109269

Gonçalves S, Kilian L (2004) Bootstrapping autoregressions with conditional heteroskedasticity of unknown form. J Econ 123:89–120

Guentner J, Henßler J (2021) Exogenous oil supply shocks in opec and non-opec countries, Energy J 42

Güntner JH (2014) How do international stock markets respond to oil demand and supply shocks? Macroecon Dyn 18:1657–1682

Güntner JH, Linsbauer K (2018) The effects of oil supply and demand shocks on us consumer sentiment. J Money Credit Bank 50:1617–1644

Hamilton JD (1983) Oil and the macroeconomy since world war II. J Polit Econ 91:228–248

Hamilton JD (2009) Causes and consequences of the oil shock of 2007-08, Tech Rep, National Bureau of Economic Research

Hamilton JD (2011) Nonlinearities and the macroeconomic effects of oil prices. Macroecon Dyn 15:364–378

Herrera AM, Karaki MB (2015) The effects of oil price shocks on job reallocation. J Econ Dyn Control 61:95–113

Herrera AM, Karaki MB, Rangaraju SK (2017) Where do jobs go when oil prices drop? Energy Econ 64:469–482

Herrera AM, Rangaraju SK (2020) The effect of oil supply shocks on us economic activity: What have we learned? J Appl Economet 35:141–159

Känzig DR (2021) The macroeconomic effects of oil supply news: evidence from opec announcements. Am Econ Rev 111:1092–1125

Karaki MB (2018) Asymmetries in the responses of regional job flows to oil price shocks. Econ Inq 56:1827–1845

Karaki MB (2018b) Oil prices and state unemployment rates, Energy J 39

Kilian L (2008) The economic effects of energy price shocks. J Econ Literature 46:871–909

Kilian L (2008) Exogenous oil supply shocks: how big are they and how much do they matter for the us economy? Rev Econ Stat 90:216–240

Kilian L (2009) Not all oil price shocks are alike: disentangling demand and supply shocks in the crude oil market. Am Econ Rev 99:1053–69

Kilian L (2014) Oil price shocks: causes and consequences. Annu Rev Resour Econ 6:133–154

Kilian L (2017) The impact of the fracking boom on arab oil producers, Energy J 38

Kilian L (2019) Measuring global real economic activity: Do recent critiques hold up to scrutiny? Econ Lett 178:106–110

Kilian L (2022) Facts and fiction in oil market modeling. Energy Econ 110:105973

Kilian L (2022b) Understanding the estimation of oil demand and oil supply elasticities, Energy Econ p 105844

Kilian L, Hicks B (2013) Did unexpectedly strong economic growth cause the oil price shock of 2003–2008? J Forecast 32:385–394

Kilian L, Lee TK (2014) Quantifying the speculative component in the real price of oil: the role of global oil inventories. J Int Money Financ 42:71–87

Kilian L, Lütkepohl H (2017) Structural vector autoregressive analysis. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Kilian L, Murphy DP (2014) The role of inventories and speculative trading in the global market for crude oil. J Appl Economet 29:454–478

Kilian L, Park C (2009) The impact of oil price shocks on the US stock market. Int Econ Rev 50:1267–1287

Kilian L, Zhou X (2018) Modeling fluctuations in the global demand for commodities. J Int Money Financ 88:54–78

Kilian L, Zhou X (2020) The econometrics of oil market var models, FRB of Dallas Working Paper

Lee K, Ni S, Ratti RA (1995) Oil shocks and the macroeconomy: the role of price variability, Energy J 16

Loungani P (1986) Oil price shocks and the dispersion hypothesis, Rev Econ Statistics, pp 536–539

Nonejad N (2020) An observation regarding hamilton’s recent criticisms of kilian’s global real economic activity index. Econ Lett 196:109582

Ramey VA, Vine DJ (2011) Oil, automobiles, and the us economy: How much have things really changed? NBER Macroecon Annu 25:333–368

Romer CD, Romer DH (2010) The macroeconomic effects of tax changes: estimates based on a new measure of fiscal shocks. Am Econ Rev 100:763–801

Shank SE, Haugen SE (1987) The employment situation during 1986: job gains continue, unemployment dips. Monthly Lab Rev 110:3

WashingtonPost N (1986) Oil falls below \$10 a barrel, rebounds on bush remarks

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Zeina Alsalman declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by the author.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

I am thankful to Ana Maria Herrera, Jochen Güntner, and Lutz Kilian for helpful comments and suggestions.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Alsalman, Z. Oil price shocks and US unemployment: evidence from disentangling the duration of unemployment spells in the labor market. Empir Econ 65, 479–511 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-022-02351-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-022-02351-0