Abstract

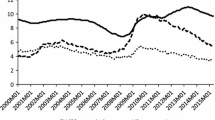

Major economic events, such as the global financial crisis, are episodes of identifiable duration that differ from other time periods. Using monthly data on the unemployment rate, labour force participation rate and employment for Australia for the period from 1978 to 2012, we estimate a Markov-switching SVAR model to examine the relationship between unemployment and labour force participation and the performance of the Australian labour market. Three distinct labour market regimes are identified. We find that the labour market switches between periods of low unemployment and high participation, prolonged periods of relative stability and short, sharp periods of high unemployment and low participation. A key finding is that, due to the behaviour of workers not in the labour force, the long-term effect of an upswing in labour hiring results in a lower unemployment rate and a lower labour force participation rate.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Claessens et al. (2009) identify the quarter in which OECD countries entered recession. The USA, along with Ireland and Iceland, entered recession in the first quarter of 2008. Australia had just one quarter of negative output growth (the fourth quarter of 2008).

The job finding probability is closely (and positively) related to matching market tightness (Shimer 2005).

Monthly labour market gross flows data (for the period October 1997 to April 2013) reveal that the average values for \(f^{U}\) and \(f^{H}\) are 0.215 and 0.045, respectively. The fact that the two job finding rates for the USA are so different forms the basis for Flinn and Heckman’s (1983) observation that being unemployed and not in the labour force are behaviourally distinct labour market states. See also Hall (2006), who attributes the procyclicality of the job finding rate in large measure to the behaviour of those out of the labour force finding employment.

The ratio of job losers to job leavers among the ranks of the unemployed from the second quarter of 2001 to the second quarter of 2013 averages about 1.55. See the following footnote for the data source and definitions.

The data are from the SuperTable files (UQ1) in Labour Force, Australia, Detailed, Quarterly (ABS cat. 6291.0.55.003) and for the second quarter of 2001 to the second quarter of 2013. Job losers are unemployed people who have worked for 2 weeks or more in the past 2 years and left that job involuntarily: that is, they were laid off or retrenched from that job; left that job because of their own ill-health or injury; the job was seasonal or temporary; or their last job was running their own business and the business closed down because of financial difficulties. Job leavers are unemployed people who have worked for 2 weeks or more in the past 2 years and left that job voluntarily—that is, because (for example) of unsatisfactory work arrangements/pay/hours; the job was a holiday job or they left the job to return to studies; or their last job was running their own business, and they closed down or sold that business for reasons other than financial difficulties. As in Davis et al. (2006), a quadratic polynomial is fitted to the data in both figures.

The use of seasonally adjusted data is standard in this literature (see, e.g. Schwartz 2012). The data used are for the period February 1978 to October 2012 and available from the Australian Bureau of Statistics at: http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/DetailsPage/6202.0Jul%202012?OpenDocument.

We also considered other specifications that allow the autoregressive parameters to switch between regimes. However, these parameters were not significantly different from each other across the regimes for each of the variables. This subsequently reduced the univariate models to only switching between the regimes defined by differences in the intercept and variance of the residuals. Justification for a changing intercept for each regime is provided by Bianchi and Zoega (1998). For 17 OECD countries, they find shifts in the mean of the unemployment rate after large shocks and that the effects persist (measured as the sum of coefficients in the autoregressive process). Small shocks have no such effects. They argue that their findings are consistent with hysteresis models of unemployment.

See Psaradakis and Spagnolo (2003), Psaradakis and Spagnolo (2006), Herwartz and Lütkepohl (2011) and Lütkepohl and Netšunajev (2014) for the selection of the number of regimes. The tests for the number of regimes for each of the variables are not reported for the sake of brevity. We find that all three criteria suggest that the optimal number of regimes for all variables is three. We discuss this procedure in more depth in the next section, where we report the results for the multivariate model.

As for the univariate models, we also considered other specifications to allow the autoregressive parameters to switch between regimes. However, these autoregressive parameters were not significantly different from each other across the regimes in each equation. Thus, the models only switch between the regimes as defined by differences in the intercept and the variance–covariance matrices of the residuals.

For all the SVAR models (two regimes, three regimes and four regimes), the AR parameters are not statistically different from each other across regimes. The only difference observed is through the switching in intercept and covariances of the residuals across the equations. We report the results for the model with three regimes (which is statistically optimal) for the sake of brevity. We have also estimated each equations of the system independently to establish the number of regimes for each equation and find that the optimal number of regimes to be three. The results are not reported for the sake of brevity.

For details of the algorithm, see Krolzig (1997).

The equality of regime means is tested for each equation separately. The results are reported in Table 7 of Appendix. The results show that intercepts for the regimes are different from each other at a 5 % level of significance for all three equations. The equality of means is also examined pairwise and further confirms that there are at least three regimes for our analysis. In addition, the equality of regime variances was also tested for each equation separately to make sure that the covariance matrices are different between the regimes. The results are reported in Table 8 of Appendix. The results show that the variances for the regimes are different from each other at a 5 % level of significance for all three equations. Similar testing conducted on a model with four regimes found that the intercept and variances for the fourth regime are not statistically different from the third regime at a 5 % level of significance for all three equations, confirming that three regimes are the optimal number for our analysis.

As we shall see below, the moderate regime could also be classified as a moderate to mild recessionary regime.

The results from estimating a two equation model with UR and LFPR reveal that the same relationship exists between those variables. These results are available in a separate “Appendix” available from the authors.

The expected length of remaining in a particular regime is calculated as \(1/(1 - p_\mathrm{ii})\).

Job losses are countercyclical, and job finding rates are procyclical, i.e. when economic activity contracts and employment falls, job losses increase and job finding decreases. From the perspective of gross flows, the pool of the unemployed shrinks. Fujita and Ramey (2009) show that this “pool size effect” outweighs the effect of increases in the job finding rate. This effect is further reinforced because while the job loss rate reacts almost simultaneously with respect to movements in the cycle, the impact of the job finding rate and gross hiring reacts with some lag. This is a possible explanation for the ‘jobless recoveries’ phenomenon. Similarly, Shimer (2013) shows that the share of inactive workers rises during recessions as some of the large pool of unemployed workers drop out of the labour force. The underlying developments are subject to debate in the USA and Australia. In Australia’s case, Dixon et al. (2005) argue that increases in unemployment are driven by job separations (with greater flows from employment to both unemployment and not in the labour force), while Ponomareva and Sheen (2010) argue that increases in the unemployment rate are driven by lower job finding rates and diminished flows from unemployment to employment.

See Krolzig (1997) for a detailed discussion of impulse response functions for MS-VAR models with regime-invariant VAR matrices. Since the final model switches between the three regimes for the intercept and variances of the residuals, the impulse responses are similar across the three regimes.

References

Autor DH (2011) The unsustainable rise of the disability rolls in the United States: causes, consequences, and policy options. Working paper no. 17697, National Bureau of Economic Research

Bianchi M, Zoega G (1998) Unemployment persistence: Does the size of the shock matter? J Appl Econom 13(3):283–304

Billio M, Di Sanzo S (2006) Granger-causality in Markov switching models. Department of Economics Research Paper Series 20WP, University Ca’Foscari of Venice

Blanchard OJ, Katz LF (1992) Regional evolutions. Brook Pap Econ Act 1:1–75

Brückner M, Pappa E (2012) Fiscal expansions, unemployment and labor force participation: theory and evidence. Int Econ Rev 53(4):1205–1228

Burns AF, Mitchell WC (1946) Measuring business cycles. National Bureau of Economic Research, New York

Cai L (2010) The relationship between health and labour force participation: evidence from a panel data simultaneous equation model. Labour Econ 17(1):77–90

Cai L, Gregory RG (2003) Inflows, outflows and the growth of the disability support pension (DSP) program. Aust Soc Policy 2002(03):121–143

Claessens S, Kose MA, Terrones ME (2009) What happens during recessions, crunches and busts? Econ Policy 24(60):653–700

Clements MP, Krolzig H-M (1998) A comparison of the forecast performance of Markov-switching and threshold autoregressive models of US GNP. Econom J 1:C47–C75

Davis SJ, Faberman RJ, Haltiwanger J (2006) The flow approach to labor markets: new data sources and micro-macro links. J Econ Perspect 20(3):3–26

Debelle G, Vickery J (1999) Labour market adjustment: evidence on interstate labour mobility. Aust Econ Rev 32(3):249–263

Dellas H, Sakellaris P (2003) On the cyclicality of schooling: theory and evidence. Oxf Econ Pap 55(1):148–172

Dixon R, Freebairn J, Lim GC (2005) An examination of net flows in the Australian labour market. Aust J Lab Econ 8(1):25–42

Elsby MWL, Hobijn B, Şahin A (2010) The labor market in the Great Recession. Brook Pap Econ Act Spring, 1–48

Elsby MWL, Michaels R, Solon G (2009) The ins and outs of cyclical unemployment. Am Econ J Macroecon 1(1):84–110

Fujita S, Ramey G (2009) The cyclicality of separation and job finding rates. Int Econ Rev 50(2):415–430

Furceri D, Mourougane A (2009) Financial crises: past lessons and policy implications. OECD Economics Department working paper no. 668

Gaston N, Rajaguru G (2013) How an export boom affects unemployment. Econ Model 30(1):343–355

Gong X (2011) The added worker effect for married women in Australia. Econ Rec 87(278):414–426

Hall RE (2006) Job loss, job finding and unemployment in the U.S. economy over the past 50 years. NBER Macroecon Annu 2005 20:57–101

Hall SG, Psaradakis Z, Sola M (1999) Detecting periodically collapsing bubbles: a Markov-switching unit root test. J Appl Econom 14(2):143–154

Hamilton JD (1989) A new approach to the economic analysis of nonstationary time series and the business cycle. Econometrica 57(2):357–384

Hamilton JD (2005) What’s real about the business cycle? Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review, July/August, pp 435–452

Herwartz H, Lütkepohl H (2011) Structural vector autoregressions with Markov switching: combining conventional with statistical identification of shocks. Economics Working Papers ECO2011/11, European University Institute

Kendig H, Wells Y, O’Loughlin K, Heese K (2013) Australian baby boomers face retirement during the global financial crisis. J Aging Soc Policy 25(3):264–280

Kilian L, Park C (2009) The impact of oil price shocks on the U.S. stock market. Int Econ Rev 50(4):1267–1287

Krolzig H-M (1997) Markov-switching vector autoregressions: modelling, statistical inference, and application to business cycle analysis. Lecture notes in economics and mathematical systems, issue 454. Springer, Berlin

Lanne M, Lütkepohl H, Maciejowska K (2010) Structural vector autoregressions with Markov switching. J Econ Dyn Control 34(2):121–131

Lazear EP, Spletzer JR (2012) The United States labor market: Status quo or a new normal? Working paper no. 18386, National Bureau of Economic Research

Lundberg S (1985) The added worker effect. J Labor Econ 3(1):11–37

Lütkepohl H, Netšunajev A (2014) Disentangling demand and supply shocks in the crude oil market: how to check sign restrictions in structural VARs. J Appl Econom 29:479–496

Miller P, Volker P (1989) Socioeconomic influences on educational attainment: evidence and implications for the tertiary education finance debate. Aust J Stat 31(1):47–70

Netsunajev A (2013) Reaction to technology shocks in Markov-switching structural VARs: identification via heteroskedasticity. J Macroecon 36:51–62

Nickell S, Nunziata L, Ochel W, Quintini G (2003) The Beveridge curve, unemployment and wages in the OECD from the 1960s to the 1990s. In: Aghion P, Frydman R, Stiglitz J, Woodford M (eds) Knowledge, information, and expectations in modern macroeconomics: in honour of Edmund S. Phelps. Princeton University Press, Princeton, pp 394–431

O’Loughlin K, Humpel N, Kendig H (2010) Impact of the global financial crisis on employed Australian baby boomers: a national survey. Aust J Ageing 29(2):88–91

Ponomareva N, Sheen J (2010) Cyclical flows in Australian labour markets. Econ Rec 86(Special Issue):35–48

Psaradakis Z, Spagnolo N (2003) On the determination of the number of regimes in Markov-switching autoregressive models. J Time Ser Anal 24(2):237–252

Psaradakis Z, Spagnolo N (2006) Joint determination of the state dimension and autoregressive order for models with Markov regime switching. J Time Ser Anal 27(5):753–766

Reinhart CM, Rogoff KS (2009) The aftermath of financial crises. Am Econ Rev 99(2):466–472

Schwartz J (2012) Labor market dynamics over the business cycle: evidence from Markov switching models. Empir Econ 43(1):271–289

Shimer R (2004) Search intensity. Unpublished manuscript, University of Chicago

Shimer R (2005) The cyclical behavior of equilibrium unemployment and vacancies. Am Econ Rev 95(1):25–49

Shimer R (2012) Reassessing the ins and outs of unemployment. Rev Econ Dyn 15(2):127–148

Shimer R (2013) Job search, labor force participation, and wage rigidities. In: Acemoglu D, Arellano M, Dekel E (eds) Advances in economics and econometrics: Tenth World Congress, Vol 2, Econometric Society Monographs (Book 50). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 197–234

Wasmer E (2009) Links between labor supply and unemployment: theory and empirics. J Popul Econ 22(3):773–802

Yashiv E (2007) US labor market dynamics revisited. Scand J Econ 109(4):779–806

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Noel Gaston and Gulasekaran Rajaguru: The comments of Felix Chan, Phillip Chindamo and two anonymous referees are gratefully acknowledged. The authors are also grateful to Lance Fisher and Jan-Egbert Sturm for feedback on an earlier version of the paper. As customary, the authors bear the responsibility for all errors and omissions.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gaston, N., Rajaguru, G. A Markov-switching structural vector autoregressive model of boom and bust in the Australian labour market. Empir Econ 49, 1271–1299 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-015-0920-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-015-0920-4