Abstract

Revealed preference tests are frequently used to check data on the behavior of agents for consistency with economic theory. Unfortunately these tests lack a stochastic element and thus one violation of revealed preference causes a rejection of the behavior being tested. To remedy this lack of a stochastic element in revealed preference analysis, we suggest a general, simple, and intuitive statistical procedure to test whether the observed number of violations is more consistent with a pre-specified type of non-degenerate behavior than with rational behavior. We illustrate this general procedure with an example using uniform random behavior that allows researchers to test whether the actual number of violations of revealed preference is more consistent with uniform random behavior than rational behavior. This statistical test takes advantage of the fact that nonparametric revealed preference tests involve known prices and expenditures. Our illustrative example is accompanied by some Monte Carlo exercises showing that the uniform test performs very well. We implement our test using datasets from two well-known economic experiments. One is a dataset on altruistic choices from Andreoni and Miller (Econometrica 70:737–753, 2002). The second is a dataset on the choices made by subjects who act within a token economy from Battalio et al. (West Econ J 11:411–428, 1973) and Cox (Econ J 107:1054–1078, 1997). We find that for a majority of subjects in one altruistic behavior sub-experiment uniform random behavior can be rejected in favor of rational behavior at the 10 % level of significance. For all but one subject, living in the token economy, uniform random behavior cannot be rejected. For that one subject in the token experiment uniform random behavior is rejected in favor of perverse economic behavior.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

This discussion is closely related to the power of static revealed preference tests, see Andreoni and Harbaugh (2006). Blundell et al. (2003) suggested one possible solution to this problem by combining non-parametric revealed preference procedures with parametric methods over regions of the data where the non-parametric tests may lack power. The quite different procedure proposed in this paper derives and specifies the statistical properties over a set of revealed preference violations without having to impose any distributional assumptions.

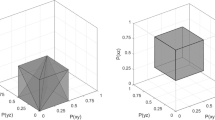

All other combinations of observed behavior lead to zero violations in Fig. 1. Thus, the random probability of their occurrences does not affect the expected number of violations.

Since our graphical examples are two good and two budget constraint examples, a violation of revealed preference in our examples is a violation of WARP, SARP, or GARP.

Some notation: We denote \(\mathbb R _{+}^{K}=\left\{ \mathbf x \in \mathbb R ^{K}:\mathbf x >\mathbf 0 \right\} \) and \(\mathbb R _{++}^{K}=\left\{ \mathbf x \in \mathbb R ^{K}:\mathbf x >>\mathbf 0 \right\} \), where the notation \(\mathbf x >\mathbf y \) refer to \(x_{k}>y_{k}\), but not \(x_{k}=y_{k}\) for all \(k=1,\ldots ,K\) (i.e., \(\mathbf x \ne \mathbf y \)). Also, \(\mathbf x >>\mathbf y \) means \(x_{k}>y_{k}\) for all \(k=1,\ldots ,K\).

The reason for us focusing on this sub-experiment is simply because the subjects were allowed to conduct their choices over more budgets. The subjects in one of Andreoni and Miller’s (2002) sets of experiments faced 8 budgets while the subjects in the other faced 11 budgets. Now, since the power of a test increases with the number of sample observations, we expect to be able to draw sharper conclusions from the experiments with 11 observations. Of course, the results from Andreoni and Miller’s (2002) experiments with 8 observations are available upon request.

Similar to the previous alturistic experiments, we should also keep in mind the relatively low sample size of 8 observations, which may affect the power of the test.

References

Afriat SN (1967) The construction of utility functions from expenditure data. Int Econ Rev 8:67–77

Aizcorbe A (1991) A lower bound for the power of nonparametric tests. J Bus Econ Stat 9:463–467

Andreoni J, Harbaugh WT (2006) Power indices for revealed preference tests. University of Wisconsin-Madison, Department of Economics Working paper 2005–10

Andreoni J, Miller J (2002) Giving according to GARP: an experimental test of the consistency of preferences for altruism. Econometrica 70:737–753

Battalio RC, Kagel JH, Winkler RC, Fisher EB, Basmann RL, Krasner L (1973) A test of consumer demand theory using observations of individual consumer purchases. West Econ J 11:411–428

Beatty T, Crawford I (2011) How demanding is the revealed preference approach to demand. Am Econ Rev 101:2782–2795

Becker GS (1962) Irrational behavior and economic theory. J Political Econ 70:1–13

Blundell RW, Browning M, Crawford IA (2003) Nonparametric Engel curves and revealed preference. Econometrica 71:205–240

Bronars SG (1987) The power of nonparametric tests of preference maximization. Econometrica 55:693–698

Cox JC (1997) On testing the utility hypothesis. Econ J 107:1054–1078

de Perreti P (2005) Testing the significance of the departures from utility maximization. Macroecon Dyn 9:372–397

Dean M, Martin D (2011) Testing for rationality with consumption data: Demographics and heterogeneity. Brown University Working paper 2011–11

Epstein LG, Yatchew AJ (1985) Non-parametric hypothesis testing procedures and applications to demand analysis. J Econ 30:149–169

Fleissig AR, Whitney GA (2005) Testing for the significance of violations of Afriat’s inequalities. J Bus Econ Stat 23:355–362

Gross J (1995) Testing data for consistency with revealed preference. Rev Econ Stat 78:701–710

Harbaugh WT, Krause K, Berry TR (2001) GARP for kids: on the development of rational choice behavior. Am Econ Rev 91:1539–1545

Houthakker HS (1950) Revealed preference and the utility function. Economica 17:159–174

Leroux A, Leroux J (2004) Fair division with no information. Econ Theory 24:351–371

McCausland WJ (2009) Random consumer demand. Economica 76:89–107

Samuelson PA (1938) A note on the pure theory of consumer’s behaviour. Economica 5:61–71

Swofford JL, Whitney GA (1986) Flexible functional forms and the utility approach to the demand for money: a nonparametric analysis. J Money Credit Banking 18:383–389

Varian HR (1982) The nonparametric approach to demand analysis. Econometrica 50:945–973

Varian HR (1985) Nonparametric analysis of optimizing behavior with measurement error. J Econ 30:445–458

Varian HR (2006) Revealed preference. In: Szenburg M, Ramrattan L, Gottesman AA (eds) Samuelsonian economics and the twenty-first century. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Woronow A (1993) Generating random numbers on a simplex. Comput Geosci 19:81–88

Ziegler G (1998) Lectures on polytopes. Springer, Berlin

Acknowledgments

We thank David Edgerton, Barry Jones, and seminar participants at the “Measurement Error: Econometrics and Practice” conference in Birmingham, UK in July 2007 and at the School of Economics at University College, Dublin for comments on earlier versions of the paper. We also thank James Andreoni and James Cox for providing the data. Hjertstrand thanks the Department of Economics and Finance, University of South Alabama for hospitality during a visit, and the Jan Wallander and Tom Hedelius Foundation for research support. Swofford would like to thank the Department of Economics at Lund University for their hospitality during a visit.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hjertstrand, P., Swofford, J.L. Are the choices of people stochastically rational? A stochastic test of the number of revealed preference violations. Empir Econ 46, 1495–1519 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-013-0724-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-013-0724-3