Abstract

Purpose

The evaluation of measurement properties such as reliability, measurement error, construct validity, and responsiveness provides information on the quality of the scale as a whole, rather than on an item level. We aimed to synthesize the measurement properties referring to reliability, measurement error, construct validity, and responsiveness of the Victorian Institute of Sport Assessment questionnaires (Achilles tendon—VISA-A, greater trochanteric pain syndrome—VISA-G, proximal hamstring tendinopathy—VISA-H, patellar tendon—VISA-P).

Methods

A systematic review was conducted according to Consensus-based Standards for the Selection of Health Measurement Instruments methodology (COSMIN). PubMed, Cochrane, CINAHL, EMBASE, Web of Science, SportsDiscus, grey literature, and reference lists were searched. Studies assessing the measurement properties concerning reliability, validity, and responsiveness of the VISA questionnaires in patients with lower limb tendinopathies were included. Two reviewers assessed the methodological quality of studies assessing reliability, validity, and responsiveness using the COSMIN guidelines and the evidence for these measurement properties. A modified Grading of Recommendations Assessment Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach was applied to the evidence synthesis.

Results

There is moderate-quality evidence for sufficient VISA-A, VISA-G, and VISA-P reliability. There is moderate-quality evidence for sufficient VISA-G and VISA-P measurement error, and high-quality evidence for sufficient construct validity for all the VISA questionnaires. Furthermore, high-quality evidence exists with regard to VISA-A for sufficient responsiveness in patients with insertional Achilles tendinopathy following conservative interventions.

Conclusions

Sufficient reliability, measurement error, construct validity and responsiveness were found for the VISA questionnaires with variable quality of evidence except for VISA-A which displayed insufficient measurement error.

Level of evidence

IV.

Registration details

Prospero (CRD42018107671); PROSPERO reference—CRD42019126595.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The impact of lower limb tendinopathies on the patient, according to the International Scientific Tendinopathy Symposium Consensus from 2019, should be measured using validated outcome measures that can capture the core domains of the condition such as: functional testing, participation in life activities, psychological factors, physical function capacity, and most importantly disability via condition-specific patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) [37, 59]. The Victorian Institute of Sport Assessment (VISA) questionnaires [4, 14, 51, 61] have been recommended by the consensus statement from 2019 [59] and are used globally in many different cultures, in research and clinical practice to assess the severity of symptoms and functional disability of patients with lower limb tendinopathies [30, 37, 58]. All four VISA are self-administered questionnaires, developed in English language, consisting of eight items, and assessing the severity of symptoms in patients with Achilles tendinopathy (VISA-A), greater trochanteric pain syndrome (VISA-G), proximal hamstring tendinopathy (VISA-H), and patellar tendinopathy (VISA-P) [4, 14, 51, 61]. Six out of eight items rate pain level during daily activities and functional tests, and two items provide information on the impact of tendinopathy in physical activity or sports participation. Scores are summed up with a score approaching 100 points representing a fully functional asymptomatic individual. The last item of the PROM (item 8) contributes significantly on the total score (may range from 0 to 30 out of 100 points), is divided into three parts, and inquires about sports participation or weight bearing activities (for patients with greater trochanteric pain syndrome). The participant must answer only one part depending on their symptom level and their interference with sports participation or weight-bearing activities.

In the first part of this systematic review [27], we evaluated the content and structural validity of all patient-reported VISA questionnaires (VISA-A, VISA-G, VISA-H, and VISA P). This systematic review showed variable results and that only very-low-quality evidence exists for the content validity and unidimensionality of VISA questionnaires when assessing the severity of symptoms and disability in patients with lower limb tendinopathies. In the second part of this systematic review, we aim to evaluate the rest of the measurement properties of patient-reported VISA questionnaires. This is important as VISA measurement properties, such as reliability, measurement error, construct validity, and responsiveness have been extensively evaluated in individual studies, since their development and publication without a systematic review, to our knowledge, to provide a comprehensive overview of the quality of these measurement properties. Unlike content and structural validity, the evaluation of these measurement properties provides information on the quality of the scale as a whole, rather than on an item level [48].

The foundation of evidence-based practice and thorough research is the use of outcome measures that are psychometrically sound. The validity and reliability, as well as the responsiveness of these measurement tools, is a prerequisite in making meaningful patient-centred clinical inferences. Thus, the aim of the present systematic review was to appraise and summarize the quality of the remaining measurement properties of VISA questionnaires: reliability, measurement error, construct validity, and responsiveness.

Materials and methods

Protocol registration

The search strategy and reporting of this systematic review followed the COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments (COSMIN) methodology for systematic reviews of PROMs [48], the Cochrane group’s recommendations [20], and adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [42]. The protocol was prospectively registered in PROSPERO (CRD42019126595).

Information sources and search methods

PubMed, Cochrane, CINAHL, EMBASE, Web of Science, and SportsDiscus databases were independently searched by two reviewers (AK and MS) from database inception to 19 May 2020 without language restriction.

Grey literature was searched via OpenGrey.eu, and the following registries: Clinical Trials.gov and EU clinical trials register. Reference lists, citation tracking results, and systematic reviews were also manually searched.

The search strategy included a comprehensive PROM filter developed by the COSMIN group [9, 56] and two basic strings of key terms (names of instruments and population of interest) (Online Resource 1).

Study selection

The title and abstract of search results were independently screened by two authors (AK and MS) and full text of the remaining studies was checked against the criteria for eligibility. The reference lists of the included articles were also searched for additional potentially relevant studies [48]. A third author (VK) resolved disputes between the reviewers [31].

Eligibility criteria

Studies were eligible if they were full-text articles in peer-reviewed journals, including patients with Achilles tendinopathy, greater trochanteric pain syndrome, proximal hamstring tendinopathy, or patellar tendinopathy and evaluating at least one of the measurement properties as defined by COSMIN taxonomy [44]: reliability, measurement error, construct validity (convergent and/or known groups), responsiveness, as well as interpretability and feasibility.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The general inclusion criteria were: (a) all the types of studies assessing at least one measurement property of the VISA questionnaires (including development and not limited to validity, reliability, responsiveness, and interpretability); (b) including patients with Achilles tendinopathy, greater trochanteric pain syndrome, proximal hamstring tendinopathy, or patellar tendinopathy, as well as other groups of asymptomatic/injured individuals that were used in measurement properties assessment; and (c) only full-text articles in peer-reviewed journals. Following recommendations [48], we excluded studies that only used a VISA questionnaire as an outcome measurement instrument, for instance, randomized controlled trials, or studies in which a VISA was used in a validation study of another instrument; and criterion validity only was not an eligibility criterion due to the lack of an established gold standard for lower limb tendinopathies.

Data extraction

Data from studies meeting the inclusion criteria were extracted by two reviewers (VK and AK) independently using standardized extraction forms and cross-checked. Any disagreements were resolved by consensus. We extracted publication details, sample size, patient and condition characteristics, details on PROM administration (setting, country, language, missing items, floor and ceiling effects, and completion time), data and indices for reliability, measurement error, convergent and divergent validity, and responsiveness. Furthermore, we extracted VISA scores of groups of individuals included in each study.

Assessment of the methodological quality of single studies and evaluation of results against criteria for good measurement properties

The methodological quality of each eligible study on a measurement property was assessed separately using the COSMIN Risk of Bias checklist [43] and pre-formulated hypotheses as indicated by the COSMIN guidelines [9]. The development studies and the studies on measurement properties were assessed using COSMIN standards; boxes 6–10, including 8 items for reliability, 6 items for measurement error, 7 items for construct validity, and 13 items for responsiveness. Interpretability and feasibility (including ceiling and floor effects) are not formal measurement properties, because they do not refer to the quality of the PROM; thus, they were not evaluated; however, given that they are considered important aspects for the selection of a PROM, they were described in the systematic review [43].

Each standard and subsequently each study were rated as “very good”, “adequate”, “doubtful”, or “inadequate” quality. The methodological study quality score per measurement property was determined by the item with the lowest score (worse score counts) [48].

Subsequently, the results on each measurement property were rated against the updated criteria for good measurement properties [48, 55]. Each result was rated as “sufficient” (+), “insufficient” (−), or “indeterminate” (?). Two reviewers (AK and MS) independently rated the quality of measurement properties, while discrepancies were resolved by discussion with a third reviewer (VK).

Rating the quality of evidence

Two reviewers (AK and MS) independently rated and summarized the quality of evidence for each measurement property using a modified GRADE approach, as suggested by the Cosmin guidelines [48]. Evidence was started at high quality and downgraded according to the presence and extent of specific dimensions recommended for the quality of evidence in PROM measurement properties studies: risk of bias (methodological quality), inconsistency (unexplained inconsistency of results across studies), imprecision (total sample size), and indirectness (evidence from population different than that of interest). The results were qualitatively summarized or quantitatively pooled (where applicable) and compared against the criteria for good measurement properties to determine whether the “overall” measurement property of the PROM is sufficient (+), insufficient (−), inconsistent (±), or indeterminate (?) [48]. To rate the pooled or qualitatively summarized results as sufficient or insufficient, the criterion of at least 75% consistent results had to be met [48].

Statistical analysis

To our knowledge, there is no procedure yet defined for formal meta-analysis of intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) values. To allow for description of an interpretable value of the pooled ICC coefficients, these raw values were pooled using the R statistical platform [49] (metafor package) [60] with the variance approximated as described in Noble et al. [46] using a random effects model. The uninterpretable Fisher z-transformed values are provided (Online Resource 2). Given the statistical heterogeneity observed (Cochrane’s Q statistic and I2), moderator analysis was conducted using subject groups (i.e., patients, asymptomatic subjects, mixed groups, and at-risk subjects). Values were presented as pooled mean estimate and 95% confidence intervals (CI).

For interpretability of sub-group (i.e., patients, at-risk, asymptomatic) VISA scores, standardized mean differences (SMD) and 95% CI were calculated from pooled weighted group scores to determine the magnitude of difference of the total score (Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software).

Results

Study characteristics

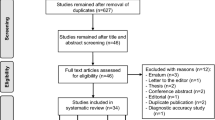

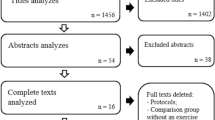

Of the original 1511 studies, 34 remained after duplicate removal. Of these, 33 met the eligibility criteria appraising measurement properties of interest of this review (Fig. 1): VISA-A [10,11,12, 19, 21, 25, 26, 33, 35, 38, 40, 51, 53, 54], VISA-G [2, 13, 14, 22], VISA-H [4, 32], and VISA-P [1, 5, 15,16,17,18, 24, 28, 34, 39, 47, 61, 62, 64].

The review team decided that there is no gold standard for measuring pain, function, and sports participation in patients with lower limb tendinopathy; hence, the criterion validity was not evaluated in this review.

Characteristics of the included study populations

Characteristics of the study population, condition, and details on instrument administration are presented in Table 1.

Quality, results, and evidence synthesis of studies evaluating reliability

VISA-A

Thirteen studies [10,11,12, 19, 21, 25, 26, 33, 35, 38, 51, 53, 54] assessed the reliability of the VISA-A in 907 patients and asymptomatic individuals. All summarized studies presented results of sufficient reliability ranging from 0.79 to 0.993 except two studies, where the reliability coefficients did not meet the criteria of ICC > 0.70. The treatment provided in Achilles tendinopathy patients [10] and the continuation of running in the “at-risk” group [33] during the test–retest period may explain these inconsistencies (Table 2).

The pooled ICC coefficient was 0.918 (Fig. 2a). By subgrouping the studies that included patients (only, or mixed group of patients and asymptomatic individuals), the pooled estimate for ICC was 0.911 (Fig. 2b). Moderator analysis did not meaningfully alter the pooled estimate (ICC = 0.914, 95% CI 0.809–1.00, I2 = 95.79%).

Forest plots of pooled ICC coefficients for the Victorian Institute of Sport Assessment scale—Achilles (VISA-A) and Patella (VISA-P). a Pooled ICC coefficients from all studies evaluated VISA-A, b pooled ICC coefficients for VISA-A studies including patients in the sample (only patients or mixed with asymptomatic individuals), c pooled ICC coefficients from all studies evaluated VISA-P, d pooled ICC coefficients for VISA-P studies including patients in the sample (only patients or mixed with asymptomatic individuals), and e pooled ICC coefficients for VISA-P studies including only patients in the sample. CI confidence intervals, ICC intraclass correlation coefficient, mixed mixed sample of participants and asymptomatic individuals

There are very-low- and moderate-quality evidences for sufficient reliability of VISA-A in a mixed population of patients, asymptomatic and at-risk individuals and in patients with Achilles tendinopathy, respectively (Table 3).

VISA-G

Three studies [2, 14, 22] assessed the reliability of the VISA-G in 239 patients and asymptomatic individuals (Table 2).

There is moderate-quality evidence for sufficient reliability of VISA-G with ICC values ranging from 0.827 to 0.99 (Table 3).

VISA-H

Two studies [4, 32] assessed the reliability of the VISA-H in 106 patients and asymptomatic individuals (Table 2).

There is low-quality evidence for sufficient reliability of VISA-G ranging from 0.90 to 0.993 (Table 3).

VISA-P

Thirteen studies [1, 5, 15, 17, 18, 24, 28, 34, 39, 47, 61, 62, 64] assessed the reliability of the VISA-P in 930 patients with patellar tendinopathy and asymptomatic individuals. All summarized studies presented results of sufficient reliability ranging from 0.74 to 0.994 except two studies that the reliability coefficients did not meet the criteria of an ICC > 0.70 (Table 2).

The pooled ICC coefficient was 0.964 (Fig. 2c). By subgrouping the studies that included only patients with patellar tendinopathy or a mixed group of individuals including patients the pooled estimates for ICC were 0.970 and 0.961, respectively (Fig. 2d, e). Moderator analysis did not meaningfully alter the pooled estimate (ICC = 0.979, 95% CI 0.931–1.00, I2 = 66.89%).

There is low- and moderate-quality evidence for sufficient reliability of VISA-P in mixed populations and in patients with patellar tendinopathy only, respectively (Table 3).

Quality, results, and evidence synthesis of studies evaluating measurement error

VISA-A

Four cross-cultural adaptations [10, 11, 19, 53] assessed the measurement error of the VISA-A in 318 patients and asymptomatic individuals (Table 2).

There is moderate-quality evidence for insufficient measurement error of the VISA-A with standard error of measurement (SEM) and smallest detectable change (SDC) values ranging from 2.53 to 7.0 and 7.0 to 19.0 points, respectively (Table 3).

VISA-G

Three studies [2, 14, 22] assessed the measurement error of the VISA-G in 239 patients and asymptomatic individuals (Table 2).

There is moderate-quality evidence for sufficient measurement error of VISA-G with SEM and SDC values ranging from 0.6 to 1.883 and 3.17 to 5.2 points, respectively (Table 3).

VISA-H

Only the development study [4] assessed the measurement error of the VISA-H in 55 patients with proximal hamstring tendinopathy and asymptomatic individuals (Table 2).

There is very-low-quality evidence for sufficient measurement error of VISA-H with SEM and SDC values ranging from 0.25 to 1.56 and 0.7 to 4.3 points, respectively (Table 3).

VISA-P

Eight studies [15, 17, 18, 24, 28, 34, 62, 64] assessed the measurement error of the VISA-P in 587 patients with patellar tendinopathy and asymptomatic individuals (Table 2).

There is moderate-quality evidence for sufficient measurement error of the VISA-P with SEM and SDC values ranging from 0.522 to 5.2 and 1.446 to 14.4 points, respectively (Table 3).

Quality, results, and evidence synthesis of studies evaluating hypotheses for construct validity

VISA-A

Eleven studies [10,11,12, 19, 21, 25, 26, 35, 51, 53, 54] assessed construct validity using as comparators generic tendon grading systems, valid and reliable lower limb PROMs (i.e., Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society, Foot and Ankle Outcome Score questionnaire), or generic measures of health status (i.e., the Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey—SF36). In addition, assessed known group’s validity by comparing the scores of patients, asymptomatic, or “at-risk” for tendinopathy individuals (Table 2).

There is high-quality evidence for sufficient hypotheses testing for construct validity of the VISA-A from consistent findings (Table 3).

VISA-G

Two studies [2, 14] assessed known groups and convergent validity using as comparator instruments the Harris Hip Score, the Oswestry Disability Index, and the Short Form 36 or comparing the VISA-G scores between patients and asymptomatic individuals (Table 2).

There is high-quality evidence for sufficient hypotheses testing for construct validity (convergent and known groups) of VISA-G from consistent findings (Table 3).

VISA-H

Two studies [4, 32] assessed construct and known group’s validity of the VISA-H in 106 patients and asymptomatic individuals (Table 2).

There is moderate- and high-quality evidence for sufficient hypotheses testing of VISA-H for convergent and known group’s validity, respectively (Table 3).

VISA-P

Eleven studies [1, 5, 15, 17, 24, 28, 34, 47, 61, 62, 64] assessed construct validity using as comparators generic tendon grading systems (i.e., Nirchl pain scale, Blazina classification system), valid and reliable lower limb PROMs (i.e., Lysholm questionnaire, Cincinnati knee scale, and Kujala scoring questionnaire), or generic measures of health status (i.e., SF36), as well as assessed known group’s validity by comparing the scores of patients, asymptomatic, or “at-risk” for tendinopathy individuals (Table 2).

There is high-quality evidence for sufficient hypotheses testing for construct validity (convergent and known groups) of the VISA-P from consistent findings (Table 3).

Quality, results, and evidence synthesis of studies evaluating responsiveness

VISA-A

Three studies using the construct approach tested hypotheses for responsiveness by comparing the VISA-A change scores with the SF-36 [19] or by assessing the effect magnitude of an intervention in patients with Achilles tendinopathy [19, 21, 40] (Table 2).

There is low-quality evidence for sufficient responsiveness of the VISA-A as compared with SF-36, and high-quality evidence for sufficient responsiveness following rehabilitation with a minimally important change (MIC) of 6.5 points (Table 3).

VISA-G

One study [13] tested hypotheses for responsiveness by comparing the VISA-G change scores with the Oxford Hip Score and the Harris Hip Score, or by assessing the magnitude of an intervention in patients with symptomatic partial or full thickness tendon tears (Table 2).

There are very-low and low-quality evidences of the VISA-G, for sufficient responsiveness as compared with other PROMs and before and after surgery and rehabilitation with an MIC of 29.0 points (Table 3).

VISA-H

Only the development study [4] tested hypotheses for responsiveness by comparing the VISA-H change scores with the Nirschl phase rating scale and a generic tendon grading system or by assessing the magnitude of a conservative intervention in patients with proximal hamstring tendinopathy (Table 2).

There is very-low-quality evidence for sufficient responsiveness of the VISA-H as compared with other outcome measures with no information regarding their measurement properties. There is moderate-quality evidence for sufficient responsiveness following rehabilitation with an MIC of 22.0 points (Table 3).

VISA-P

Four studies tested hypotheses for responsiveness by comparing the VISA-P change scores with the Nirchl score [61] and the global rating of change scale [18], or by assessing the magnitude of a surgical or a conservative intervention in patients with patellar tendinopathy (Table 2) [17, 18, 61, 62].

There is high-quality evidence for sufficient responsiveness of the VISA-P as compared with other outcome measures, and low-quality evidence for sufficient responsiveness following physiotherapy with an MIC of 16.0 points (Table 3).

Interpretability and feasibility

The distribution of the VISA scores and the group differences for patients and other groups of individuals according to each lower limb tendinopathy are depicted in Fig. 3.

Upper portion shows mean values and normalised distribution (violin) of the VISA scores according to lower limb tendinopathy and groups of individuals included in each study. Lower portion shows the standardized mean differences in group comparisons with effect sizes in standardized mean differences. Data are depicted according to age groups and the size of each circle is proportional to the sample size. In studies reporting median and interquartile range we calculated the mean [36] and standard deviation [63] from relevant equations. For standardized mean difference calculations, we used the pooled weighted values for each comparison

One study per VISA calculated the MIC using anchor-based methods. The MIC in 15 patients with insertional Achilles tendinopathy [40] was 6.5, in 56 patients with symptomatic partial or full thickness gluteal tendon tears [13] was 29.0, in 16 patients with proximal hamstring tendinopathy [4] was 22.0, and in 90 patients with patellar tendinopathy [18] was 16.0 points.

Most of the studies did not report on missing items. Three studies reported no missing items [2, 4, 14], while in one study [53] described that 10.6% of the administered questionnaires were incomplete or erroneously filled. No study identified floor and ceiling effects of the scores of patients with tendinopathy; however, a group ceiling effect in studies was seen in asymptomatic individuals [14, 22].

The VISA questionnaires are free to use, self-administered, require no equipment, no specialized training, minimum of communication between administrator and patient, and they are not diagnostic tools. Average completion time for VISA-A and VISA-P was less than 5 min, while for VISA-G ranged from 1.2 to 8.5 min and 2.1 min to 10 min in asymptomatic individuals and patients, respectively. No information was reported for VISA-H completion time.

Discussion

The most important finding of this study was that the VISA questionnaires presented sufficient reliability, measurement error, construct validity, and responsiveness with variable quality of evidence. Only the VISA-A displayed insufficient measurement error.

There is moderate-quality evidence for sufficient VISA-A, VISA-G, and VISA-P reliability, moderate-quality evidence for sufficient VISA-G and VISA-P measurement error, high-quality evidence for sufficient VISA construct validity, as well as high-quality evidence for sufficient responsiveness only for VISA-A in patients with insertional Achilles tendinopathy following conservative interventions. The evidence for the rest of the measurement properties in VISA questionnaires was sufficient and of low and very-low qualities.

Test–retest reliability, stability of the condition, and recall bias

An important assumption made in reliability evaluation is that patients are stable on the construct to be measured between the repeated measurements [48]. The selection of an appropriate time interval for test and retest depends on the interplay of two inversely related domains: recall bias and stability of the clinical condition. The time interval should be short enough to ensure that patients are stable and at the same time long enough to prevent recall bias [48]. The quality evaluation of the reliability and measurement error in all included studies was substantially affected (all downgraded for risk of bias) by these two domains. Most studies failed to provide evidence that patients were stable at the second administration of the PROM, or provided evidence of significant differences between test and retest in patients with chronic Achilles tendinopathy [10, 21, 54]. Methods to measure the stability of the condition have been proposed, such as asking the patients to self-rate their condition as unchanged at the second administration of the PROM or using a global rating of change scale [29, 48]. Instead, most studies attempted to ensure stability of the condition by decreasing the time between the repeated administrations and consequently increasing the risk of recall bias. It can be assumed that the symptoms of a chronic lower limb tendinopathy would not change within a week; however, 72% of the included studies did not report the duration of symptoms of the included tendinopathy sample making this assumption unsafe. The possibility of recruitment of patients with ongoing tendinopathy could not be excluded, where a significant improvement or deterioration can be experienced in a short period of time with decreased or continued activity and tendon load [41]. We suggest future studies assessing PROMs’ reliability and measurement error to carefully define an adequate time interval between repeated measurements by avoiding treatment or consultation with a health care provider, asking the patients to confirm that their clinical condition has not changed, ensuring similar conditions in PROMs administration, and following the recommended standards for reporting participant characteristics in tendinopathy research (i.e., symptoms duration) [48, 50].

The pooled or summarized reliability coefficients for the VISA questionnaires displayed sufficient reliability with values greater than 0.82. The pooled ICC estimates presented substantial heterogeneity despite the subgroup analyses; thus, these results should be interpreted with caution. Exploratory inclusion of ICC moderators did not: (a) substantially affect the pooled estimate; (b) decrease the heterogeneity; or (c) suggest moderation by the subgroup of participants.

Although measurement error (SDC) of the VISA questionnaires requires further evaluation; VISA-G, VISA-H, and VISA-P displayed moderate quality of sufficient measurement error not exceeding the MIC. A change in VISA score greater than 4.0, 4.0, and 11.0 points represents a true change for VISA-G, VISA-H, and VISA-P; respectively. The VISA-A only displayed insufficient measurement error; however, larger scale responsiveness studies are required to assess the MIC in other subgroups except insertional Achilles tendinopathy patients. Despite that SDC has significant clinical utility, 53% of the included studies did not report values for measurement error suggesting the need for future studies to evaluate measurement error in patients of different ages and levels of physical activity, or different subgroups of patients within the clinical spectrum of tendinopathy. Moreover, it is suggested that future studies present the differences between test and retest using Bland–Altman methods as this method shows a relationship between the plotted differences and the magnitude of measurements (i.e., proportional error), depicting any systematic bias (i.e., absolute systematic error) and identifies possible outliers allowing meaningful clinical inferences [3].

Construct validity and hypotheses testing of the VISA questionnaires

The extent to which the results of hypotheses testing for construct validity are consistent with the predefined hypotheses will be evidence supporting validity of the PROM [23]. The VISA questionnaires exhibited high-quality evidence for sufficient known group’s validity, demonstrating that the VISA total score can validly discriminate patients from asymptomatic or at-risk individuals. Pooled weighted VISA scores of patients as compared to asymptomatic and at-risk individuals presented very large effect sizes, in contrast to the significant, but small effect size, differences between groups without tendinopathy (Fig. 3).

Construct validity of a PROM is preferably tested against a “gold standard” [48]. To our knowledge, a gold standard outcome measure does not exist in tendinopathy, as well as for many musculoskeletal conditions which are accompanied with functional disability and pain [23, 45]. Hence, construct validity can be assessed by comparing the PROM of interest with other PROMs that measure a similar construct. In our review, 50% of the included studies used as comparator scales PROMs without information about their reliability and validity, while 32% used SF-36 and 27% region-specific valid and reliable PROMs. Despite that tendinopathy has a unique clinical presentation that significantly differs from other lower limb musculoskeletal conditions [41], region-specific PROMs would be more appropriate for future studies assessing construct validity of the VISA questionnaires (i.e., Lower Extremity Functional Scale, Foot and Ankle Outcome Score), rather than generic or non-validated scales and PROMs.

Responsiveness and interpretation of the VISA scores

For a PROM to be clinically useful, it must first be psychometrically sound in terms of reliability and validity, but also must be able to detect real change in health status (sensitivity to change) and display the ability to detect absence of change when there is no real change (specificity to change) [7, 8]. From a clinical perspective, the MIC score can be used in establishing a therapeutic threshold in lower limb tendinopathy through the VISA questionnaires. However, beyond inherent methodological limitations in MIC calculation [7, 8], such as the use of distribution or anchor-based methods, or the use of “a little better” or “much better” as the cut-off value from a global rating of change scale, several other factors seem to influence the stability and mediate the variability of MIC score. The potential usefulness of the MIC as a single point estimate for both researchers and clinicians, contrasts with evidence suggesting that the stability of a single MIC score remains an elusive notion in the area of interpretability [6,7,8].

Moreover, the MIC is context-specific, is not a fixed property of a PROM, and is dependent on characteristics of the population, condition severity, chronicity, intervention, and period of follow-up [7, 57]. To illustrate: a 6.5-point improvement which exceeds the MIC for insertional Achilles tendinopathy following a 12-week conservative intervention has a different meaning for patients with higher levels of disability (i.e., baseline VISA-A score of 38 points—self-rated significant improvement reported by 80% of the patients) [40] compared to lower levels of disability (i.e., baseline VISA-A score of 53 points—self-rated significant improvement by 46% of the patients) [52].

Strengths and weaknesses of the review, and future study recommendations

Despite the limitations in reliability evaluation, the VISA questionnaires displayed consistently sufficient reliability across studies and groups, suggesting that test–retest reliability should not be a priority when developing new language versions. Rather, resources should be directed towards assessment of other clinimetric properties, such as content and construct validity, measurement error, and responsiveness.

All VISA questionnaires have been categorized as “B” PROMs, meaning that may have the potential to be recommended, but further content and structural validation studies are needed to assess their quality [27]. Clinicians and researchers should interpret the measurement error of the PROMs with caution, given its dependence on MIC, and remain mindful that these scores are patient-population-specific (not generalizable). With regard to responsiveness, future studies should: elucidate how the baseline characteristics can be separated from regression to the mean, standardize methods of assessment, evaluate the MIC scores in subgroups of tendinopathy across the spectrum of the condition, and establish a range of values (instead of a single point estimate) for intervention outcomes.

A degree of subjectivity was necessary in the rating of the standards of the criteria of these newly formed guidelines, though the involvement of three reviewers and the pre-specified criteria helped to minimize the possibility of bias.

The post hoc decision for statistical analyses is acknowledged as a limitation. In addition, given the lack of guidelines performing meta-analyses using the ICC, the robustness of the assumptions we made for estimating the group effect remains to be investigated.

Finally, the exclusion of studies that only used a VISA questionnaire as an outcome measurement instrument (i.e., randomized controlled trials) following COSMIN suggestions can be considered as a limitation. It can be suggested to the COSMIN developers to consider this especially with regard to the clinimetric domains of construct validity and responsiveness in future guideline updates.

Conclusion

The VISA questionnaires seem to have sufficient clinimetric evidence for reliability, measurement error, construct validity, and responsiveness, except VISA-A that displayed insufficient clinimetric evidence for measurement error. Lack of adherence to guidelines significantly affected the quality of evidence for VISA reliability and measurement error. In construct validity (convergent) evaluation, the majority of the comparator instruments were non condition specific or lacked sufficient psychometric properties. Updating and modifications of the VISAs are required to reflect the needs across the spectrum of age, activity, and functional capacity of patients with lower limb tendinopathies.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- COSMIN:

-

Consensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement Instruments

- ICC:

-

Intraclass correlation coefficient

- MIC:

-

Minimally important change

- PROM:

-

Patient-reported outcome measures

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- SF36:

-

Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey

- SDC:

-

Smallest detectable change

- SEM:

-

Standard error of measurement

- SMD:

-

Standardized mean differences

- VISA:

-

Victorian Institute of Sport Assessment

- VISA-A:

-

Victorian Institute of Sport Assessment Achilles tendinopathy

- VISA-G:

-

Victorian Institute of Sport Assessment greater trochanteric pain syndrome

- VISA-H:

-

Victorian Institute of Sport Assessment proximal hamstring tendinopathy

- VISA-P:

-

Victorian Institute of Sport Assessment patellar tendinopathy

References

Acharya GU, Kumar A, Rajasekar S, Samuel AJ (2019) Reliability and validity of Kannada version of Victorian Institute of Sports Assessment for patellar tendinopathy (VISA-P-K) questionnaire. J Clin Orthop Trauma 10:S189–S192

Beaudart C, Gillier M, Bornheim S, Van Beveren J, Bruyère O, Kaux JF (2020) French translation and validation of the “Victorian Institute of Sports Assessment for Gluteal Tendinopathy” questionnaire. PM R 5:454. https://doi.org/10.1002/pmrj.12391

Bland JM, Altman DG (1986) Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet 1:307–310

Cacchio A, De Paulis F, Maffulli N (2014) Development and validation of a new visa questionnaire (VISA-H) for patients with proximal hamstring tendinopathy. Br J Sports Med 4848:39–44

Celebi MM, Kose SK, Akkaya Z, Zergeroglu AM (2016) Cross-cultural adaptation of VISA-P score for patellar tendinopathy in Turkish population. Springerplus 5:1453

Cook CE (2008) Clinimetrics corner: the minimal clinically Important Change Score (MCID): a necessary pretense. J Man Manip Ther 16:E82-83

Copay AG, Chung AS, Eyberg B, Olmscheid N, Chutkan N, Spangehl MJ (2018) Minimum clinically important difference: current trends in the orthopaedic literature, part I: upper extremity: a systematic review. JBJS Rev 6:e1

Copay AG, Eyberg B, Chung AS, Zurcher KS, Chutkan N, Spangehl MJ (2018) Minimum clinically important difference: current trends in the orthopaedic literature, part II: lower extremity: a systematic review. JBJS Rev 6:e2

COSMIN. COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments (COSMIN) http://www.cosmin.nl. Accessed 18 May 2020

de Knikker R, El Hadouchi M, Velthuis M, Wittink H (2008) The Dutch version of the Victoria Institute of Sports Assessment—Achilles (VISA-A) questionnaire: cross-cultural adaptation and validation in Dutch patients with Achilles tendinopathy, Nederlands. Tijdschrift Voor Fysiotherapie 118:34–41

de Mesquita GN, de Oliveira MNM, Matoso AER, de Moura AG, de Oliveira RR (2018) Cross-cultural adaptation and measurement properties of the Brazilian Portuguese Version of the Victorian Institute of Sport Assessment-Achilles (VISA-A) Questionnaire. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 48:567–573

Dogramaci Y, Kalaci A, Kucukkubas N, Inandi T, Esen E, Yanat AN (2011) Validation of the VISA-A questionnaire for Turkish language: the VISA-A-Tr study. Br J Sports Med 45:453–455

Ebert JR, Fearon AM, Smith A, Janes GC (2019) Responsiveness of the Victorian Institute for Sport Assessment for Gluteal Tendinopathy (VISA-G), modified Harris hip and Oxford hip scores in patients undergoing hip abductor tendon repair. Musculoskelet Sci Pract 43:1–5

Fearon AM, Ganderton C, Scarvell JM, Smith PN, Neeman T, Nash C et al (2015) Development and validation of a VISA tendinopathy questionnaire for greater trochanteric pain syndrome, the VISA-G. Man Ther 20:805–813

Frohm A, Saartok T, Edman G, Renström P (2004) Psychometric properties of a Swedish translation of the VISA-P outcome score for patellar tendinopathy. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 5:49

Hernandez-Sanchez S, Abat F, Hidalgo MD, Cuesta-Vargas AI, Segarra V, Sanchez-Ibañez JM et al (2017) Confirmatory factor analysis of VISA-P scale and measurement invariance across sexes in athletes with patellar tendinopathy. J Sport Health Sci 6:365–371

Hernandez-Sanchez S, Hidalgo MD, Gomez A (2011) Cross-cultural adaptation of VISA-P score for patellar tendinopathy in Spanish population. J Orthop Sports Phys 41:581–591

Hernandez-Sanchez S, Hidalgo MD, Gomez A (2014) Responsiveness of the VISA-P scale for patellar tendinopathy in athletes. Br J Sports Med 48:32–38

Hernandez-Sanchez S, Poveda-Pagan EJ, Alakhdar-Mohmara Y, Hidalgo MD, Fernandez-De-Las-Penas C, Arias-Buria JL (2018) Cross-cultural Adaptation of the Victorian Institute of Sport Assessment-Achilles (VISA-A) Questionnaire for Spanish Athletes with Achilles Tendinopathy. J Orthop Sports Phys 48:111–120

Higgins JPT, Green S (2011) Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions, version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration

Iversen JV, Bartels EM, Jørgensen JE, Nielsen TG, Ginnerup C, Lind MC et al (2016) Danish VISA-A questionnaire with validation and reliability testing for Danish-speaking Achilles tendinopathy patients. Scand J Med Sci Sports 26:1423–1427

Jorgensen JE, Fearon AM, Molgaard CM, Kristinsson J, Andreasen J (2020) Translation, validation and test-retest reliability of the VISA-G patient-reported outcome tool into Danish (VISA-G.DK). PeerJ 8:14

Kamper SJ (2019) Reliability and validity: linking evidence to practice. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 49:286–287

Kaux JF, Delvaux F, Oppong-Kyei J, Beaudart C, Buckinx F, Croisier JL et al (2016) Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Victorian Institute of Sport Assessment-Patella Questionnaire for French-speaking patients with patellar tendinopathy. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 46:384–390

Kaux JF, Delvaux F, Oppong-Kyei J, Dardenne N, Beaudart C, Buckinx F et al (2016) Validity and reliability of the French translation of the VISA-A questionnaire for Achilles tendinopathy. Disabil Rehabil 38:2593–2599

Keller A, Wagner P, Izquierdo G, Cabrolier J, Caicedo N, Wagner E et al (2018) Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the VISA-A questionnaire for Chilean Spanish-speaking patients. J Orthop Surg Res 13:177

Korakakis V, Kotsifaki A, Stefanakis M, Sotiralis Y, Whiteley R, Thorborg K (2021) Evaluating lower limb tendinopathy with Victorian Institute of Sport Assessment (VISA) questionnaires. A systematic review shows very-low quality evidence for their content and structural validity—part I. (Personal communication)

Korakakis V, Patsiaouras A, Malliaropoulos N (2014) Cross-cultural adaptation of the VISA-P questionnaire for Greek-speaking patients with patellar tendinopathy. Br J Sports Med 48:1647–1652

Korakakis V, Saretsky M, Whiteley R, Azzopardi MC, Klauznicer J, Itani A et al (2019) Translation into modern standard Arabic, cross-cultural adaptation and psychometric properties’ evaluation of the Lower Extremity Functional Scale (LEFS) in Arabic-speaking athletes with Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) injury. PLoS ONE 14:e0217791

Korakakis V, Whiteley R, Tzavara A, Malliaropoulos N (2018) The effectiveness of extracorporeal shockwave therapy in common lower limb conditions: a systematic review including quantification of patient-rated pain reduction. Br J Sports Med 52:387–407

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA et al (2009) The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ 339:b2700

Locquet M, Bornheim S, Colas L, Van Beveren J, Bruyère O, Reginster JY et al (2019) French translation of the Victorian Institute of Sport Assessment Scale for proximal hamstring tendinopathy (VISA-H). Journal de Traumatologie du Sport 36:217–221

Lohrer H, Nauck T (2009) Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the VISA-A questionnaire for German-speaking achilles tendinopathy patients. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 10:134–134

Lohrer H, Nauck T (2011) Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the VISA-P Questionnaire for German-speaking patients with patellar tendinopathy. J Orthop Sports Phys 41:180–190

Lohrer H, Nauck T (2010) Validation of the VISA-A-G Questionnaire for German-speaking patients suffering from Haglund’s Disease. Sportverletz Sportschaden 24:98–106

Luo D, Wan X, Liu J, Tong T (2018) Optimally estimating the sample mean from the sample size, median, mid-range, and/or mid-quartile range. Stat Methods Med Res 27:1785–1805

Macdermid JC, Silbernagel KG (2015) Outcome evaluation in tendinopathy: foundations of assessment and a summary of selected measures. J Orthop Sports Phys 45:950–964

Maffulli N, Longo UG, Testa V, Oliva F, Capasso G, Denaro V (2008) Italian translation of the VISA-A score for tendinopathy of the main body of the Achilles tendon. Disabil Rehabil 30:1635–1639

Maffulli N, Longo UG, Testa V, Oliva F, Capasso G, Denaro V (2008) VISA-P score for patellar tendinopathy in males: adaptation to Italian. Disabil Rehabil 30:1621–1624

McCormack J, Underwood F, Slaven E, Cappaert T (2015) The minimum clinically important difference on the VISA-A and LEFS for patients with insertional Achilles tendinopathy. Int J Sports Phys Ther 10:639–644

Millar NL, Silbernagel KG, Thorborg K, Kirwan PD, Galatz LM, Abrams GD et al (2021) Tendinopathy. Nat Rev Dis Primers 7:1

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 339:332–336

Mokkink LB, de Vet HCW, Prinsen CAC, Patrick DL, Alonso J, Bouter LM et al (2018) COSMIN risk of bias checklist for systematic reviews of patient-reported outcome measures. Qual Life Res 27:1171–1179

Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, Alonso J, Stratford PW, Knol DL et al (2010) The COSMIN study reached international consensus on taxonomy, terminology, and definitions of measurement properties for health-related patient-reported outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol 63:737–745

Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, Alonso J, Stratford PW, Knol DL et al (2010) The COSMIN checklist for assessing the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties of health status measurement instruments: an international Delphi study. Qual Life Res 19:539–549

Noble S, Scheinost D, Constable RT (2019) A decade of test-retest reliability of functional connectivity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroimage 203:116157

Park BH, Seo JH, Ko MH, Park SH (2013) Reliability and validity of the Korean version VISA-P Questionnaire for patellar tendinopathy in adolescent elite volleyball athletes. Ann Rehabil Med 37:698–705

Prinsen CAC, Mokkink LB, Bouter LM, Alonso J, Patrick DL, de Vet HCW et al (2018) COSMIN guideline for systematic reviews of patient-reported outcome measures. Qual Life Res 27:1147–1157

R Core Team (2020) A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna

Rio EK, Mc Auliffe S, Kuipers I, Girdwood M, Alfredson H, Bahr R et al (2020) ICON PART-T 2019-International Scientific Tendinopathy Symposium Consensus: recommended standards for reporting participant characteristics in tendinopathy research (PART-T). Br J Sports Med 54:627–630

Robinson JM, Cook JL, Purdam C, Visentini PJ, Ross J, Maffulli N et al (2001) The VISA-A questionnaire: a valid and reliable index of the clinical severity of Achilles tendinopathy. Br J Sports Med 35:335–341

Rompe JD, Furia J, Maffulli N (2008) Eccentric loading compared with shock wave treatment for chronic insertional Achilles tendinopathy. J Bone Jt Surg Am 90:52–61

Sierevelt I, van Sterkenburg M, Tol H, van Dalen B, van Dijk N, Haverkamp D (2018) Dutch version of the Victorian Institute of Sports Assessment-Achilles questionnaire for Achilles tendinopathy: reliability, validity and applicability to non-athletes. World J Orthop 9:1–6

Silbernagel KG, Thomee R, Karlsson J (2005) Cross-cultural adaptation of the VISA-A Questionnaire, an index of clinical severity for patients with Achilles tendinopathy, with reliability, validity and structure evaluations. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 6:12

Terwee CB, Bot SDM, de Boer MR, van der Windt DAWM, Knol DL, Dekker J et al (2007) Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol 60:34–42

Terwee CB, Jansma EP, Riphagen II, de Vet HC (2009) Development of a methodological PubMed search filter for finding studies on measurement properties of measurement instruments. Qual Life Res 18:1115–1123

Terwee CB, Roorda LD, Dekker J, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, Peat G, Jordan KP et al (2010) Mind the MIC: large variation among populations and methods. J Clin Epidemiol 63:524–534

van der Vlist AC, Winters M, Weir A, Ardern CL, Welton NJ, Caldwell DM et al (2020) Which treatment is most effective for patients with Achilles tendinopathy? A living systematic review with network meta-analysis of 29 randomised controlled trials. Br J Sports Med. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2019-101872

Vicenzino B, de Vos RJ, Alfredson H, Bahr R, Cook JL, Coombes BK et al (2020) ICON 2019-International Scientific Tendinopathy Symposium Consensus: there are nine core health-related domains for tendinopathy (CORE DOMAINS): Delphi study of healthcare professionals and patients. Br J Sports Med 54:444–451

Viechtbauer W (2010) Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J Stat Softw 36:1–48

Visentini PJ, Khan KM, Cook JL, Kiss ZS, Harcourt PR, Wark JD (1998) The VISA score: an index of severity of symptoms in patients with jumper’s knee (patellar tendinosis). J Sci Med Sport 1:22–28

Wageck BB, De Noronha MA, Lopes AD, Da Cunha RA, Takahashi RH, Costa LOP (2013) Cross-cultural adaptation and measurement properties of the Brazilian Portuguese version of the Victorian Institute of Sport Assessment-Patella (VISA-P) scale. J Orthop Sports Phys 43:163–171

Wan X, Wang W, Liu J, Tong T (2014) Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med Res Methodol 14:135

Zwerver J, Kramer T, van den Akker-Scheek I (2009) Validity and reliability of the Dutch translation of the VISA-P questionnaire for patellar tendinopathy. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 10:102

Funding

Open access funding provided by the Qatar National Library. No funding was received for conducting this review.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to this work and the authorship of this manuscript. VK planned, coordinated the idea, conducted the search, analyzed results, wrote and reviewed the manuscript; AK, MS, and RW coordinated the idea, analyzed the results, provided writing content and reviewed; YS conducted the search, wrote and reviewed the manuscript; and KT provided writing, editing, and review support.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Informed consent

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Korakakis, V., Whiteley, R., Kotsifaki, A. et al. A systematic review evaluating the clinimetric properties of the Victorian Institute of Sport Assessment (VISA) questionnaires for lower limb tendinopathy shows moderate to high-quality evidence for sufficient reliability, validity and responsiveness—part II. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 29, 2765–2788 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-021-06557-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-021-06557-0