Abstract

In this study, the optimal layout of the principal structural members forming a building frame are sought, considering both gravity and lateral loads. The plastic design layout optimization formulation is used, considering the multiple load cases arising from the requirements of a well-known structural design code. The superposition approach is shown to be applicable to the three primary load case problems involved. It is found that the optimal layouts identified differ from those obtained when bracing is sought for a pre-existing frame, already designed to resist gravity loads. A significant finding is that a parameter related to the difference in vertical and lateral loads to be applied in the applicable load cases is a key factor determining the optimal layout of frame members. Since applicable load cases are design code dependent, this also indicates that optimal layout will be strongly influenced by choice of design code. Simple benchmark problems and a practical building design example are used to illustrate the concepts explored.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Ensuring adequate resistance to lateral loads is central to the design of any building. When designing a building, structural engineers normally rely on codes of practice, which generally require that several separate load cases are considered. Often the load case which involves application of the maximum lateral load includes design gravity loads which are not at their maximum value. This is because it is considered improbable that maximum gravity loads will coincide with, say, maximum wind loads. As a result, in many bracing optimization studies, it is first assumed that the sizes of the main columns and beams in a structural frame are determined by consideration of gravity load cases (only), and that these members will have sufficient strength to play their required roles in resisting lateral loads without needing to be resized; this scenario has been considered by various workers (e.g. Kim et al. 1998; Liang et al. 2000; Terán-Gilmore and Coeto 2011; Stromberg et al. 2012), and was recently considered in more detail by Lu et al. (2018). There are in contrast relatively few examples of what may be termed ‘holistic’ optimization of the structural frame, in which all load cases are considered when identifying the locations and sizes of members forming the frame of a building. This runs contrary to recent practice in the field of structural engineering, where, for example, diagrid exoskeleton frames are increasingly being used to resist both vertical and lateral loads.

Considering previous research involving the holistic optimization of building frames, Chan et al. (1995) considered multiple gravity and wind load combinations from the American Institute of Steel Construction standard when performing the size optimization of members forming a 50-storey building frame. Burry et al. (2005) simultaneously applied lateral and gravity loading in a shape optimization problem for a pre-defined structure, whilst Moon et al. (2007) considered diagrid bracing systems, using the angles between bracing members as parameters to be varied in order to optimize the lateral stiffness of the structure. In addition to these academic studies, optimization has been used in the practical design of landmark structures. For example in the design of the diagrid structure for the Swiss Re (‘Gherkin’) building in London, a parametric optimization scheme was used to design the external form to resist gravity and wind loading. Instead of using prescribed joint positions, the external form was defined by a small number of parameters, enabling a complex geometric model to be manipulated rapidly (Foster and Partners 2005). For the design of the visually striking CCTV headquarters building in Beijing, an iterative optimization process was used in the design of the bracing, adding or removing diagonals to meet the strength and stiffness requirements associated with a Level 1 earthquake (Carroll et al. 2008).

Whilst these studies have yielded interesting findings, it appears that no rigorous academic studies of the holistic frame layout design problem have been conducted to date, in which the locations and sizes of principal members forming a building frame are sought. Addressing this is the main driver for the present study. Both theoretical and numerical layout optimization approaches are used to identify optimal framing systems capable of withstanding gravity loads only and also combined gravity plus lateral loading scenarios.

The paper is organized as follows: Section 2 describes the design optimization problem that will be considered and identifies a key parameter related to the load cases which turns out to greatly influence the layouts of the optimal building frames identified; Section 3 describes application of the techniques described to single and multi-storey building design examples; Section 4 describes application to the design of a small office building; finally, conclusions from the study are drawn in Section 5.

2 Holistic design optimization problem

2.1 Layout optimization

The optimal layouts of discrete members in a framework can be identified using the layout optimization procedure, originally described by Dorn et al. (1964). In this procedure, nodes are laid out in a grid across the design domain, with all possible interconnections between nodes forming a ‘ground structure’. The basic single load case ‘plastic’ layout optimization formulation for a two-dimensional truss problem can be stated as follows:

where there are m members and n nodes in the problem, and where V represents the volume of the structure, \(\mathbf {q}^{T}=\{q^{+}_{1},q^{-}_{1},q^{+}_{2},q^{-}_{2},...,q^{+}_{m},q^{-}_{m} \}\), \(\mathbf {c}^{T}=\{l_{1}/\sigma ^{+}_{1},l_{1}/\sigma ^{-}_{1},l_{2}/\sigma ^{+}_{2},l_{2}/\sigma ^{-}_{2},...,l_{m}/\sigma ^{+}_{m},l_{m}/\sigma ^{-}_{m}\}\), where and \(l_{i},q^{+}_{i},q^{-}_{i},\sigma ^{+}_{i},\sigma ^{-}_{i}\) represent, respectively, the length, tensile member force, compressive member force, tensile stress capacity and compressive stress capacity of member i. B is a 2n × 2m equilibrium matrix and \(\mathbf {f}=\left \{f^{x}_{1},f^{y}_{1},f^{x}_{2},f^{y}_{2},...,f^{x}_{{\kern 1.7pt}n\phantom {D\!\!\!\!}},f^{y}_{{\kern 1.7pt}n\phantom {D\!\!\!\!}}\right \}\), where \(f^{x}_{j}\) and \(f^{y}_{j}\) represent the component of load applied to node j in the x and y directions respectively. This problem is in a form suitable for solution using linear programming (LP); the adaptive ‘member adding’ solution procedure proposed by Gilbert and Tyas (2003) can be used to reduce the cost of the computations involved.

2.2 Practical design considerations

Although it is common when designing a building frame manually to first design members to resist gravity loads (i.e. the constituent beams and columns), and to then design bracing elements, this may not lead to the best design. For example, it is possible that in the case of a tall, slender, frame that the design of the columns may be partly determined by the loads induced in them by the lateral load. Additionally, decoupling the different load cases in this way may mean that more optimal ‘holistic’ designs are missed. Therefore in this paper, all principal load cases are considered in the optimization.

As stated by Lu et al. (2018), for the design of steel framed buildings, British Standard 5950-1:2000 suggests the following load combinations:

where Gk is the characteristic permanent load, Qk is the characteristic imposed load and Wk is the characteristic wind load. (For sake of simplicity notional horizontal forces are neglected.)

To tackle the resulting design problem, three assumptions were introduced by Lu et al. (2018):

-

Assumption 1: The loads generated in the columns in load case (2b) and (2c) are always less than those resulting from load case (2a).

-

Assumption 2: Vertical gravity loads are only carried by the columns in all load cases.

-

Assumption 3: The sizes of pre-existing horizontal members (i.e. floor beams and/or slabs) are dominated by the gravity load case, (2a), and the axial loads induced in them by lateral load cases (2b) and (2c) are small in comparison.

Here all of these assumptions are removed. This means that vertical loads can be resisted by any frame member, and the sizes of the column members may be partly governed by the lateral load cases.

2.3 Parameter governing the optimal layout, r VH

Using the British Standard load cases (2a–2c), and with Assumptions 1, 2 and 3 removed, a parameter governing the optimal layout can be identified. To establish this, Rozvany’s work on optimization with multiple load cases (Rozvany et al. 2014) and the superposition method of Rozvany and Hill (1978) will be used.

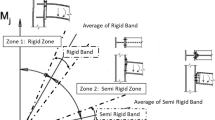

Figure 1a shows a graphical depiction of the load cases in (2a–2c). Here V is the vertical load in load cases (2b) and (2c) (i.e. 1.0Gk + 1.2Qk) and ΔV is the additional vertical load in load case (1) (i.e. 0.4Gk + 0.4Qk). Here, ΔH is used to represent the difference in horizontal (lateral) load between the gravity and lateral load cases; since the horizontal loads in the first load case are equal to zero, ΔH = H.

Use of superposition approach to derive the optimization result of multiple load cases: a three load cases based on British Standard load case combination, where V = 1.0Gk + 1.2Qk, ΔV = 0.4Gk + 0.4Qk, ΔH = 1.2Wk, where Gk, Qk and Wk are, respectively, characteristic permanent, imposed and wind loads; b as a but with additional dummy load case added to enable the superposition principle to be applied; c using superposition, the solution to b can be obtained by superimposing the individual results from four single load case problems, \(\overline {p}_{1}\) to \(\overline {p}_{4}\)

The optimized solution to the problem shown in Fig. 1a can be obtained using the superposition approach put forward by Rozvany and Hill (1978). However, this approach requires there to be 2n load cases, with n being a positive integer. Following Rozvany et al. (2014), a fourth, dummy load case p4 can be introduced, comprising vertical loads V −ΔV. According to Property 3 in Rozvany et al. (2014), since ΔV > 0, the optimized result for the problems shown in Fig. 1a and b must be identical. Providing the problem shown in Fig. 1b satisfies the specific conditions of the superposition approach, then the optimized solution can be obtained by superimposing the optimized results of four single component load cases \(\overline {p}_{1}\) to \(\overline {p}_{4}\); see Fig. 1c. Derivation of the component load cases \(\overline {p}_{1}\) to \(\overline {p}_{4}\) is presented in Appendix 1.

Using the superposition approach, the optimum structure for all four load cases can be obtained by superimposing the optimal layouts for each of the four individual component load cases. Referring to Fig. 1c, it is obvious that the optimal layout for load case \(\overline {p}_{1}\) will be vertical columns running along the outer edges of the domain. Also, it is obvious that the optimal layout for load case \(\overline {p}_{4}\) will comprise no members at all (since there are no applied loads). Therefore, the optimal bracing layout can be obtained simply by superimposing the optimal layouts arising from load cases \(\overline {p_{2}}\) and \(\overline {p_{3}}\), each obtained using the basic single load case layout optimization formulation, Eq. (1). As these latter layouts depend only on ΔV and ΔH, a new parameter rVH = ΔV/ΔH can be introduced as the parameter that controls the form of the optimal layout. Table 1 shows a sample calculation of rVH. To verify the correctness of the superposition approach described, solutions were also obtained for sample problems using the standard multiple load case LP formulation, as shown in Fig. 2 (details of the formulation are given in Appendix 2).

Numerical verification of superposition approach: a example with rVH = 3; b example with rVH = 6, where rVH is the parameter governing layout for multiple load case problems. On the left hand side are optimized results from single component load cases \(\overline {p}_{2}\) and \(\overline {p}_{3}\), see Fig. 1c, and on the right hand side are multiple load case results. Red and blue bars represent, respectively, members taking tensile and compressive forces. For the multiple load case results, the force distribution shown corresponds to the load case with horizontal (lateral) loads acting from left to right

The finding that there is a parameter rVH which governs the optimal layout is significant. Since different design codes stipulate that different combinations of loads are involved in the various load cases to be considered, this indicates that the optimal layout will be strongly influenced by the choice of design code. This fact is unlikely to have been anticipated by the code writers.

3 Examples: simple single and multi-storey braced frames

In this section, examples of the relationships between rVH and the optimal layout are presented for two types of braced bay, one with loading applied only at the top corners of the design domain, and the other with the frame split into square vertical bays with loading at each ‘floor’ level. The numerical multiple loading layout optimization approach described in Appendix 2 is used.

3.1 Problem definition

Figure 3 shows the design domain and load and support conditions for the cases considered in this study. For sake of simplicity, the aspect ratio of the design domain of all cases has been fixed to 4:1. Table 2 presents the values of the load parameter V and H in Fig. 3. In the study, V is kept constant but the horizontal load H is varied, replicating a changing external environment. For the vertical load V defined by the British Standard the ratio of the vertical load in the gravity and wind load cases can be denoted c, where:

Therefore, from (3), it is clear that cmin = 1.33 when Gk = 0 and cmax = 1.40 when Qk = 0. This means that the horizontal load H equals \(\frac {(c-1)P}{r_{\text {VH}}}\) and \(-\frac {(c-1)P}{r_{\text {VH}}}\) in load cases p2 and p3 respectively, where P is a reference load (see Table 2). For the examples documented, c has been taken as 1.35, though with checks later undertaken using c = 1.33 and c = 1.40 to verify that the main findings were largely unaffected by this choice.

Loads for single- and multi-storey bracing layout optimization study: a single-storey cases; b multi-storey cases; values of V and H are given in Table 2

The volumes of the optimized layouts are compared with two other layouts: standard cross bracing and the modified layout identified by Stromberg et al. (2012). Note that Stromberg et al. (2012) studied both problems involving multiple horizontal loads applied through the height of a building and problems involving only a single horizontal load applied to the top of a building, the latter resembling the cantilever problem considered in Section 4.8 of Hemp (1973). Since the structures obtained in both cases were found to be similar, the same Stromberg module layout is used here for both single- and multi-storey problems. (Note that members are re-sized for each specific case.)

3.2 Optimal layout results

Figures 4 and 5 show the optimal layouts and corresponding normalized volumes for the single and multi-storey frames described in Section 3.1. Note that simple (pinned) frame connections have been assumed in the models.

Single-storey frame example: comparison of volumes and optimized layouts based on British Standard loading with c = 1.35 and rVH = (0.4Gk + 0.4Qk)/(1.2Wk), where c is the ratio of the vertical load between load cases (i.e. (1.4Gk + 1.6Qk)/(1.0Gk + 1.2Qk)); all volumes are normalized against the volumes of standard cross bracing systems; red and blue bars represent, respectively, members taking tensile and compressive forces when lateral loads are applied from left to right

Multi-storey frame example: comparison of volumes and optimized layouts based on British Standard loading with c = 1.35 and rVH = (0.4Gk + 0.4Qk)/(1.2Wk), where c is the ratio in vertical load between load cases (e.g. (1.4Gk + 1.6Qk)/(1.0Gk + 1.2Qk)); all volumes are normalized against the volumes of standard cross bracing systems; red and blue bars represent, respectively, members taking tensile and compressive forces when lateral loads are applied from left to right

Firstly, as expected, the optimized bracing can be observed to always be more efficient (i.e. to consume less material) than both standard cross bracing and Stromberg bracing. However, the differences between the normalized volumes of the different layouts are comparatively small (maximum difference is 7%). This is partly because the normalized volume includes both the volume of vertical columns and the volume of interconnecting bracing elements.

Secondly, it is clear that as rVH increases, the optimized layouts tend to include highly inclined members to transmit the applied vertical loading more directly towards the supports. This is at variance with the finding by Lu et al. (2018), who suggest that there should be a 45∘ intersection angle between columns and bracing member pairs; however, this observation only applies if the columns are assumed to have infinite reserves of strength, which is not the case here.

Thirdly, it is clear that whilst Stromberg bracing is more efficient than standard cross bracing when rVH is low, the situation is reversed when rVH is high. This is a result of the fact that the shallow inclined members of the Stromberg bracing layout are most suitable for cases when horizontal (lateral) loads are significant. In such cases it can be observed that Stromberg bracing has a much simpler layout than the optimized layouts, but the associated volume is only slightly higher. This suggests that Stromberg bracing provides a very practical solution for cases when horizontal (lateral) loads are significant.

4 Bracing design of a small office building

Here, the optimization of a four-storey steel frame structure for a small office building is considered. In this case rVH was calculated to be 0.68 and 2.33 for the major and minor wind directions respectively.

Lateral stability of the frame is provided by the presence of braced bays through the full height of the frame (Fig. 6 shows a typical plan above ground floor level; the height between floors was 4.5m). Actions applied to this structure are shown in Table 3. Load cases for a braced bay are here assumed to be based on British Standard loads, defined in Eq. (2a–2c). For the sake of simplicity only the wind load case acting normal to the long side of the building, and the design of the bracing resisting this load is considered in the design. The steel has a yield stress of 355MPa in both tension and compression and an elastic modulus of 205 GPa.

Small office building: plan, after Brettle and Brown (2009)

The optimized bracing design is shown in Fig. 7a. To permit comparison, a conventional design is shown in Fig. 7c, depicting the bracing layout presented for the same building by Brettle and Brown (2009). Since the structure shown Fig. 7a is too complex to be fabricated using conventional approaches, a more practical alternative design was also sought. To achieve this the horizontal beams used in the conventional design (Fig. 7c) were used as pre-existing members, and a new optimization run. This yielded the intermediate optimized design shown in Fig. 7b.

To achieve the conventional design shown in Fig. 7c, Brettle and Brown (2009) kept the sizes of all columns and bracing members constant throughout the height of the frame, even though the forces in the members reduce significantly from ground to top floor. This kind of rationalization is common in practice. However, to remove the associated inefficiency, and hence to provide a fair comparison with the optimized layouts, here the members were resized, with the chosen sections being the most efficient H-section column and circular hollow sections available in the UK (Tata Steel Europe Limited 2016).

To realize the optimized designs shown in Fig. 7a and b a two-stage process was adopted. Firstly, layout optimization and geometry optimization were used to find the optimal layout of the braced bay (the 6m wide four-storey right hand bay shown in Fig. 6) and associated volume of required material (these were 0.0900m3 and 0.0976m3 for the layouts shown in Fig. 7a and b respectively, compared with 0.1032m3 for the layout shown in Fig. 7c). Secondly, in a post-optimization rationalization step the column and inclined bracing members were each assigned the most efficient Tata Steel section to transmit the required load, taking account of member buckling effects in compression members as necessary. The total steel masses of the resulting optimized bracing systems are shown in Fig. 7. The structure shown in Fig. 7a has the lowest mass, representing a 35% material saving compared to the conventional design shown in Fig. 7c (this is greater than the reduction prior to the post-optimization rationalization, of 13%, which in turn exceeds the reductions found previously due to the comparative inefficiency of the layout shown in Fig. 7c).

In addition to the strength of the bracing system, the stiffness of the frame is also checked. Linear elastic static analyses were conducted as a post-processing step for the three cases, considering load case (2b). The tip displacements for the designs shown in Fig. 7a, b and c were found to be 55.1 mm, 44.5 mm and 57.7 mm respectively, which all satisfy the design code requirements (for details see Appendix 3).

The optimized structure shown in Fig. 7b has a much simpler layout than the optimized benchmark structure (Fig. 7a) and is more structurally efficient than the original design proposed by Brettle and Brown (2009). Therefore, the structure shown in Fig. 7b may provide a fair compromise between efficiency and practicality in this case. Figure 8 shows a visualization of how this could look in reality.

Small office building: visualization of building incorporating optimized braced bay shown in Fig. 7b

5 Conclusions

Layout optimization has been used to identify optimal layouts for building frames. The following conclusions can be drawn:

-

1.

The optimal layouts obtained using the ‘holistic’ strategy adopted differ from those obtained when seeking to brace a frame comprising pre-existing members (e.g. as considered by Lu et al. 2018).

-

2.

For the simple holistic design problems involving square bays considered, the optimal layouts obtained were only slightly more efficient than the layouts incorporating 45∘ cross-bracing or Stromberg bracing (max. difference = 7%).

-

3.

When one of the applied load cases involves no lateral load, the optimal layout was found to be controlled by a parameter rVH, where rVH = ΔV/ΔH and ΔV and ΔH represent respectively the differences in vertical and horizontal load between the load cases.

-

4.

Since different design codes stipulate different combinations of loads are present in the load cases to be considered, this indicates that the optimal layout will be influenced by the choice of design code. This outcome is unlikely to have been anticipated by the code writers.

-

5.

The bracing layout presented by Stromberg et al. (2012) has been found to be very efficient in cases where the horizontal load dominates (e.g. rVH < 3). However, standard cross bracing becomes more efficient when the vertical load dominates (e.g. rVH ≥ 3).

-

6.

Adopting a holistic design strategy, in which non-vertical members are allowed to carry gravity loads as well as act as bracing members, appears to be most worthwhile in cases where the vertical load dominates (e.g. rVH ≥ 5).

-

7.

Layout optimization has been applied to the design of the frame of a small four storey office building comprising rectangular bays. This led to an unconventional frame layout and a reduction in the volume of material required compared with the conventional layout considered (13% prior to the post-optimization rationalization).

6 Replication of results

The main findings from this work can be reproduced by using numerical layout optimization to solve the example problems described.

References

Brettle ME, Brown DG (2009) Steel building design: worked examples for students. The Steel Construction Institute

BSEN 1993-1-1 (2006) Eurocode 3: Design of steel structures. Part1-1: General rules and rules for buildings

Burry J, Felicetti P, Tang J, Burry M, Xie M (2005) Dynamical structural modeling: a collaborative design exploration. Int J Archit Comput 3(1):27–42

Carroll C, Cross P, Duan X, Gibbons C, Ho G, Kwok M, Li R, Lee A, Li R, Luong A, Pope C (2008) Case Study: CCTV Building- Headquarters & Cultural Center. CTBUH Journal, Issue III

Chan CM, Grierson DE, Sherbourne AN (1995) Automatic optimal design of tall steel building frameworks. J Struct Eng 121(5):838–847

Dorn WS, Gomory RE, Greenberg HJ (1964) Automatic design of optimal structures. Journal de Mecanique 3:25–52

Foster and Partners (2005) Modeling the Swiss Re Tower. Architecture Week, 4 May

Gilbert M, Tyas A (2003) Layout optimization of large-scale pin-jointed frames. Eng Comput 20(8):1044–1064

He L, Gilbert M (2015) Rationalization of trusses generated via layout optimization. Struct Multidiscip Optim 52(4):677–694

Hemp WS (1973) Optimum structures. Oxford Engineering Science Series. Clarendon Press

Kim C, Kim H, Hwang J, Hong S (1998) Stiffness-based optimal design of tall steel frameworks subject to lateral loading. Struct Optim 15(3-4):180–186

Liang QQ, Xie YM, Steven GP (2000) Optimal topology design of bracing systems for multistory steel frames. J Struct Eng 126(7):823–829

Lu H, Gilbert M, Tyas A (2018) Theoretically optimal bracing for pre-existing building frames. Struct Multidiscip Optim 58(2):677–686

Moon KS, Connor JJ, Fernandez JE (2007) Diagrid structural systems for tall buildings: characteristics and methodology for preliminary design. Struct Des Tall Spec Build 16(2):205–230

Pritchard T, Gilbert M, Tyas A (2005) Plastic layout optimization of large-scale frameworks subject to multiple load cases, member self-weight and with joint length penalties. In: 6th World Congress of Structural and Multidisciplinary Optimization, CD-ROM proceedings, 10 pages

Rozvany G, Hill R (1978) Optimal plastic design: superposition principles and bounds on the minimum cost. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng 13(2):151–173

Rozvany GI, Sokół T, Pomezanski V (2014) Fundamentals of exact multi-load topology optimization–stress-based least-volume trusses (generalized Michell structures) - Part I: Plastic design. Struct Multidiscip Optim 50(6):1051–1078

Stromberg LL, Beghini A, Baker WF, Paulino GH (2012) Topology optimization for braced frames: combining continuum and beam/column elements. Eng Struct 37:106–124

Tata Steel Europe Limited (2016) Tata Steel sections interactive ‘Blue Book’. The Steel Construction Institute

Terán-Gilmore A, Coeto G (2011) Displacement-based preliminary design of tall buildings stiffened with a system of buckling-restrained braces. Earthq Spectra 27(1):153–182

Acknowledgements

The second and third authors acknowledge the support of EPSRC, under grant reference EP/N023471/1. The authors are also grateful to an anonymous reviewer for making a suggestion that enabled Appendix 1 to be greatly simplified.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Responsible Editor: YoonYoung Kim

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Application of principle of superposition

A superposition approach can be used to obtain the optimization solution for multiple load cases via superimposing the optimization solutions of certain single component load cases. Hemp (1973) first demonstrated that this approach could be applied with two arbitrary load cases and it was later expanded by Rozvany and Hill (1978) to be suitable for problems with more than two load cases for materials with equal permissible stresses in tension and compression. Nevertheless, in situations with more than two load cases, certain conditions need to be fulfilled for the superposition approach of Rozvany and Hill (1978) to be valid. Rozvany and Hill’s method involves the replacement of the actual load cases with associated ‘component’ load cases. In a situation with four alternative load cases (e.g. p1, p2, p3 and p4), there exist four component load cases according to the superposition approach (e.g. \(\overline {p}_{1}\), \(\overline {p}_{2}\), \(\overline {p}_{3}\) and \(\overline {p}_{4}\)) and each of them could be obtained based on the original four alternative load cases using (4).

where \(\overline {\mathbf {p}}=\{\overline {p_1}, \overline {p_2}, \overline {p_3}, \overline {p_4}\}\) is the vector of component load cases; p = {p1,p2,p3,p4} is the vector of alternative load cases.

Rozvany and Hill (1978) demonstrated that, if one of several specific conditions is met at every point in the design domain, then the superposition approach can be applied. For the current problem, which has four load cases, Condition 1 is relevant (referred to as Condition (10c) in Rozvany and Hill 1978).

Condition 1

requires, at any arbitrary point in the design domain, the stress generated by at least one of the component load cases to be zero.

Here, since every point in component load case \(\overline {p}_{4}\) has zero stress (e.g. see Fig. 1c), and given the the method used to obtain component load cases, the superposition principle is applicable. Thus, the superposition approach has been used to derive the optimized result in the case considered in Fig. 1b.

Appendix 2: Multiple load case plastic layout optimization formulation

The LP plastic truss layout optimization problem formulation for problems involving multiple load cases can be written as:

where α = 1, 2,...,M and i = 1, 2,...,m; and M, m, n represent, respectively, the number of load cases, members and nodes of the design problem; V represents total structure volume, a = {a1,a2,...,ai}, l = {l1,l2,...,li}, B is a suitable (2n × 2m) equilibrium matrix, \(\mathbf {q}^{\mathbf {T}}=\{q^{+}_{1},-q^{-}_{1},...,q^{+}_{m},-q^{-}_{m} \}\), fα is the load case vector, where \(\mathbf {f}^{\alpha }=\{{f_{1}^{x}},{f_{1}^{y}},...,{f_{n}^{x}},{f_{n}^{y}}\}^{\alpha }\); and \(a_{i},l_{i},q^{+}_{i},q^{-}_{i},\sigma ^{+}_{i},\sigma ^{-}_{i}\) represent, respectively, the cross section area, length, tensile force, compressive force, tensile stress capacity and compressive stress capacity of member i and also \(\{{f^{x}_{j}}\}^{\alpha }\) and \(\{{f^{y}_{j}}\}^{\alpha }\) represent, respectively, the x and y direction component load applied on node j in load case α.

In the resent contribution, the adaptive member adding method for multiple load case problems proposed by Pritchard et al. (2005) has been employed to reduce computational cost and the geometry optimization rationalization scheme proposed by He and Gilbert (2015) has been used to simplify the resulting layouts.

Appendix 3: Influence of second order effects

One main function of bracing is to control the second order effects induced by lateral displacements. Here, the practical design example described in Section 4 will be considered.

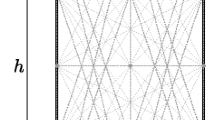

Eurocode 3 (2006) uses a parameter αcr to account for second order effects. An approximate formula for αcr is shown in (6). Eurocode 3 stipulates that, using an elastic analysis, if αcr > 10, then second order effects can be neglected. If 3 > αcr > 10, then the amplification factor given in (7) must be applied to the horizontal load. If αcr < 3, then a global second order effect analysis must be carried out.

where HEd is the total horizontal reaction at the bottom of the storey, VEd is the total design vertical load applied on the storey, h is storey height and δH,Ed is the horizontal displacement at the top of the storey, relative to the bottom, calculated using an elastic analysis.

For each structure shown in Fig. 7 values for αcr can be obtained for each storey and the minimum of these found. The minimum αcr values for Fig. 7a, b and c were found to be 19.20, 27.55 and 23.47 respectively. Since all these values are larger than 10, then, according to Eurocode 3, second order effects can be neglected.

In some circumstances αcr may drop below 10. In this case the amplification factor shown in (7) can potentially be employed during the layout optimization process to obtain an acceptable design.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Lu, H., Gilbert, M. & Tyas, A. Layout optimization of building frames subject to gravity and lateral load cases. Struct Multidisc Optim 60, 1561–1570 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00158-019-02283-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00158-019-02283-x