Abstract

This paper examines how changes in household-level risk sharing affect the marriage market. We use as our laboratory a German unemployment insurance (UI) reform that tightened means-testing based on the partner’s income. The reduced generosity of UI increased the demand for household-level risk sharing, which lowered the attractiveness of individuals exposed to unemployment risk. Because unemployment risk correlates with non-German nationality, our main finding is that the UI reform led to a decrease in intermarriage. The 2004 expansion of the European Union had a comparable effect on intermarriage for the affected nationalities. Both reforms increased marital stability, which is consistent with better selection by couples.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Living in a union with another individual is beneficial for many reasons. Besides the emotional value of companionship and love, economic motives matter for partner choice, too. First, economies of scale and household specialization increase joint consumption and utility (Muellbauer 1977; Becker 1981; Grossbard-Shechtman 1984). Second, the family facilitates risk sharing: a working spouse provides insurance against income shocks, e.g., due to unemployment or sickness (Lundberg 1985; Cullen and Gruber 2000; Shore 2010; Chiappori and Reny 2016). Under the assumption that utility is transferable within the household (Becker 1973), these economic rents generate a marital surplus that is shared between the spouses and governs marriage and divorce decisions.

A thriving literature analyzes household consumption choices, sharing rules, and welfare empirically.Footnote 1 However, relatively little is known about the quantitative importance of household-level risk sharing.Footnote 2 Existing studies either focus on time-series correlations between marriage, divorce, and unemployment rates at the macro level or on associations between unemployment and marital stability at the micro level.Footnote 3 We provide a complementary study that exploits variation in the exposure to unemployment risk and a social security reform to identify the effect of within-household insurance on marital surplus.

The idea underlying our identification strategy is that insurance against income shocks is not exclusively provided at the household level. Social insurance is a substitute. The value of this substitute varies over time as policies change, altering the demand for within-household insurance and marital surplus. Consequently, social insurance reforms can affect marital surplus and influence marriage and divorce decisions.

Our laboratory to test this hypothesis is the German unemployment insurance (UI) system. UI is a substitute for spousal insurance because unemployment benefits reduce dependence on the partner upon job loss. In January 2003, the Hartz I reform—the first of four labor market reform packages implemented in Germany between 2003 and 2005—sharply tightened the means testing of long-term unemployment assistance against the partner’s income. This increased the demand for within-household insurance and, thus, made individuals who are exposed to unemployment risk less attractive in the marriage market. We study the variation in unemployment risk at the individual level and estimate how labor market transition probabilities correlate with different observable characteristics. Using social security data from the Federal Employment Agency, we find that nationality is a quantitatively important determinant of unemployment risk, even conditional on age, education, gender, time, and region.

We compute marital surplus, our primary outcome variable, based on the Choo and Siow (2006) model of marriage market matching. In this model, agents have unobserved and heterogeneous tastes for different partner types. A key advantage of the model-based estimator is that both time-varying numbers of men and women and permanent differences between types, e.g., culture and language, are explicitly taken into account. We compute the surplus based on the flow of new marriages recorded in the German marriage register, which contains information on all legal marriages between 1997 and 2013. The stocks (numbers) of single individuals are extracted from the German Microcensus. Moreover, we use the German divorce register to study reform effects on marital stability. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first paper in the family economics literature that uses the German marriage and divorce registers.

We estimate effects of the Hartz I labor market reform on both marital surplus and marital stability in a differences-in-differences framework. Based on our finding that non-German nationality increases unemployment risk, we define as the treatment group intermarriages between German citizens and spouses of foreign nationality.Footnote 4 The idea is that intermarriages are on average more exposed to unemployment risk. We verify the composition of the treatment/control groups based on language ability (proxied by linguistic distance to German) and labor market access (proxied by European Union (EU) membership of the non-German spouse’s home country).

Our main finding is that the labor market reform had a sizable negative effect on the marital surplus of intermarriages in Germany. According to our preferred specification, the marital surplus of all treated marriages decreased by 0.410 log-points. Compared to the pre-reform marital surplus, this is equivalent to a reduction of 5.2% for marriages between Germans and citizens from the eastern European states that joined the EU in 2004 and 6.6% for marriages between Germans and citizens from countries outside the EU.Footnote 5 Regarding marital stability, we find that intermarriages formed after the reform were significantly less likely to divorce. We argue that this effect is due to positive selection. Moreover, we directly take into account the effect that the EU expansion had in 2004. It also had a sizable negative effect on the surplus of intermarriages with citizens of the new member states because the right to live and work in Germany was no longer part of the surplus. This finding is in line with Adda et al. (2022) for Italy.

The effect of the Hartz I labor market reform on the marriage market, and on intermarriages in particular, is a finding of high policy relevance. For one thing, the marriage market ramifications of a reform that was designed to reduce unemployment were most likely not intended by the policy-maker. Apart from that, intermarriages are an important vehicle for the integration of migrants (Azzolini and Guetto 2017; Adda et al. 2022). Social insurance reforms that make intermarriages less attractive may therefore conflict with a successful migration policy.

Other papers in the related literature share with ours the focus on interactions between social policy and the marriage market. Ortigueira and Siassi (2013) assess the quantitative effects of within-household risk sharing on savings and labor supply in a model with idiosyncratic income risk (Aiyagari 1994) and two decision makers within the household. Among other findings, their model matches well the elasticity of spousal labor supply with respect to UI estimated by Cullen and Gruber (2000). Low et al. (2018) find that a US welfare reform that introduced lifecycle time limits on the receipt of welfare led, inter alia, to higher marital stability. Persson (2020) argues that the elimination of survivor insurance in Sweden had effects on marriage formation decades before expected payout and, additionally, raised the divorce rate and the degree of assortative matching in the marriage market. Anderberg et al. (2020) study how raising the school-leaving age in the UK in 1972 affected partner choices both in terms of (unobserved) ability and qualification. Chen et al. (2021) study the elimination of the Social Security Student Benefit Program in the USA and show that it had implications for education-based marital sorting. Finally, our study is related to a number of papers with mixed results that study intermarriage in relation to labor market outcomes.Footnote 6

The remainder of our paper is structured as follows: Section 2 describes how marriage and unemployment rates are associated in aggregate data and studies unemployment risk at the individual level. Section 3 introduces our estimator for marital surplus. Section 4 introduces the marriage market data. Section 5 presents our empirical design, estimation results for marital surplus, and robustness checks. Section 6 contains the estimation results for marital stability and Section 7 concludes.

2 Marriage and unemployment risk

Figure 1 shows time series of the unemployment and (inter)marriage rates in Germany between 1997 and 2013. Starting from a relatively high level, the unemployment rate increased during and after the recession of the early 2000s and reached a peak of 11.2% in 2005. Thereafter, the unemployment rate decreased and reached 5.2% in 2013. Hartung et al. (2022) calculate that absent the Hartz reforms the unemployment rate in Germany would have been 50% higher at the end of this period.

Marriage and unemployment rates in Germany. Notes: The black dashed vertical line indicates the year in which the Hartz I Reform became effective (2003), the red dashed vertical line marks the year in which the EU expansion took place (2004), the blue dashed vertical line marks the year in which citizens of the 2004 EU expansion countries gained full legal EU privileges in Germany. Data source: RDC of the Federal Statistical Office and Statistical Offices of the Federal States, Marriage Register, 1997–2013, own calculations. The unemployment rate is extracted from OECD data

The number of marriages per 1000 inhabitants remained flat during the period we consider. Using the marriage register, we zoom in on the flow of new marriages and calculate the intermarriage rate, i.e., the share of all new marriages between Germans and partners with non-German citizenship. Figure 1 depicts the intermarriage rate of German males and females, respectively. The rates evolve in parallel, and intermarriage is more common for German men. In the late 1990s, intermarriage became more common while unemployment fell. Then, the rates flattened out during the recession and started to decrease markedly after 2003. Notably, this was the year in which the Hartz I reform was implemented (black dashed line). The downward trend was not affected by the EU expansion (red dashed line) and did not revert before the year 2011 when the unemployment rate approached a historical low.

The Hartz I reform is primarily known for policies designed to increase labor demand by deregulating temporary employment and subcontracted labor. A lesser-known reform element is a sharp tightening of household-level means testing of, at that time, long-term unemployment benefits. Before the reform, a maximum of 33,800 Euros of annual income of the partner was exempt from means testing, i.e., not counted against the unemployed person’s benefit entitlements. This threshold decreased by more than 60% to 13,000 Euros.Footnote 7 Because means testing is only relevant for individuals who share their household with a partner, this UI reform element specifically affected couples but not singles. This feature sets the means testing reform apart from other policy changes that affected both couples and singles. Thus, we focus on the means testing reform.Footnote 8 In Section 3, we discuss in more detail how the different reform elements affected the marriage market through the lens of the Choo and Siow (2006) model.

The temporal coincidence of decreasing intermarriage rates and the means testing reform suggests that the tightening had a specific effect on couples in which one individual is not a German national. A plausible explanation is that such couples are on average more exposed to unemployment risk. We test whether foreign nationals face a higher risk of job loss in Germany using process-generated micro data from the UI system. We rely on the Sample of Integrated Labour Market Biographies (SIAB).Footnote 9 The SIAB is a 2% random sample drawn from social security registers. We use data for the years 1997–2002.Footnote 10

One observation corresponds to an (un)employment spell with at least one of the following characteristics: (i) employment subject to social security, (ii) marginal or part-time employment, (iii) UI benefit receipt, (iv) officially registered job-seekers. We observe the precise start and end date of each spell. To identify the rate of job loss, we count transitions from employment to unemployment and from employment to inactivity. We also estimate job-finding rates based on transitions from unemployment to employment.

The covariates we consider are age, gender, nationality (German, non-German), region (municipality), and education.Footnote 11 Note that German social security records do not generally track marital status or information about the partner. We estimate Cox (1972) proportional hazard models, including nationality, gender, and education group dummies. All specifications include region and time effects but show specifications with and without age effects separately.Footnote 12 Table 1 presents the results. Columns (1) and (2) show estimated job-loss hazard rates; columns (3) and (4) show estimated job-finding rates.

Column (1) suggests that German nationals have a job loss hazard rate that is 24% lower than the rate for workers without German citizenship. However, this big difference can partly be attributed to age differences between German and foreign workers. Including age effects in column (2) reduces the hazard rate difference to 5.5% because foreign workers are on average younger. This effect is highly significant, so foreign workers are indeed more likely to lose their job. Crucially, this difference is not driven by the gender or educational composition in the respective groups because education and gender are controlled for in the regression. For transitions into employment, the hazard rate of Germans is 11% lower than the rate for foreigners without age group dummies, see column (3). Conditional on age, however, this difference is insignificant. In column (4), the hazard rate difference implies that Germans only have a 0.6% higher rate of transitioning into employment. We conclude that, conditional on age, the higher exposure of foreigners to unemployment risk is driven by an elevated job-loss hazard and not by a longer average unemployment duration.

It is worth noting that education has a non-linear effect on the hazard rates. Specifically, compared to an individual with lower secondary education and no vocational training (the reference category), basic secondary education and vocational training do not reduce the job loss risk. Individuals with a higher secondary degree even face higher job loss risks. Only university education is associated with an average job loss risk below the level of individuals with basic secondary education.

Women are roughly 7% less likely to become unemployed and about 11% less likely to move into employment compared to men in the specifications that include age effects. That is, women have on average longer employment durations, but it also takes them longer to find new jobs out of unemployment. From the estimated labor market hazard rates alone, it is therefore not clear whether intermarriages in which the female is non-native are more exposed to unemployment risk than couples in which the male is non-native. We will get back to this question below.

Based on the evidence presented in this section, we focus our analysis on intermarriages. Exposure to unemployment risk clearly differs between native and non-native workers in the German labor market, even conditional on age, education, gender, region, and time effects. Despite the non-linear effect of education on the job-loss hazard rate, an alternative strategy would be to use education as a proxy for unemployment risk. Education often plays a prominent role in studies of marriage market matching (e.g., Greenwood et al. 2016; Chiappori et al. 2017). However, while the marriage register has the big advantage of completely covering the flow of new marriages, it does not contain information on the spouses’ education, and it is legally prohibited to merge it with information from different sources at the individual level. This prevents us from using education to define partner types. Alternative German micro data sources that include education are not well-suited to study reform effects on marriage markets. The German Microcensus, which we use to calculate the single populations, does not include the year of marriage after 2004 and does not follow individuals over time. The German Socio-Economic Panel Study (GSOEP) follows households over time but attrition is likely as households form or dissolve. Thus, the marriage register is the best available data source to study the association of marriage and unemployment risk in the German context.

3 Marital surplus

To investigate how changes of unemployment insurance generosity affect the gains from marriage across heterogeneous couples, we need to measure marital surplus. We rely on a non-parametric estimator that is based on the frictionless marriage market matching model with transferable utility of Choo and Siow (2006), a workhorse model in family economics.Footnote 13 In this model, marital surplus reflects the gains from marriage for both partners, which depend on their observable types. These types are age and nationality in our application.Footnote 14

A single cross section of data on the married and single populations suffices to compute marital surplus according to the static Choo and Siow (2006) model. In our empirical application, we study reform effects on marital surplus and are interested in changes of surplus over time. Therefore, we calculate marital surplus based on the flow of new marriages in every age-nationality cell relative to the respective single stocks (details in Section 4). Essentially, we measure the flow out of singlehood. This approach is well-suited to study reform effects on the marriage market, which are hard to detect based on the slow-moving stock of married couples.Footnote 15

Formally, the types are combinations of age (a) and nationality (n). We denote the type of males and females \(m_{a, n}\) and \(f_{a, n}\), respectively. The model yields the following non-parametric estimator for type-dependent marital surplus, which we derive in Online Appendix A:

Marital surplus \(\Phi \left( f_{a, n}, m_{a, n}\right) _t\) is determined by (the log of) the ratio of new marriages between type (a, n) males and females in year t and the geometric average of the respective single populations in the same year. Thus, \(\mu (f_{a, n}, m_{a, n})_t\ge 0\), \(\mu (m_{a, n}, 0)_t \ge 0\), and \(\mu (0, f_{a, n})_t \ge 0\) denote the masses (numbers) of new marriages, single men, and single women. \(\mu (f_{a, n}, m_{a, n})_t\) is also known as the marriage matching function in the literature.Footnote 16

Intuitively, the denominator captures the number of potential matches. Thus, if the number of (new) marriages in the numerator is high relative to the denominator, estimated marital surplus will be high. Note that changes in the number of potential matches, i.e., changes in the underlying single populations are also taken into account through the denominator. For example, constant marital surplus implies that the number of new marriages adjusts proportionately to the underlying single populations, which may change over time.

Consider how the labor market reform we are interested in affects marital surplus in this model. The means-testing reform, Hartz I, affected couples but not singles. The reason is that singles do not have a partner whose income could be counted against benefit entitlements, so means testing does not affect the value of singlehood. For couples, stricter means testing reduces the gains from marriage, and the extent of this reduction depends on couples’ heterogeneous exposure to unemployment risk, which we proxy by nationality (Section 2). Therefore, the model predicts a substitution towards partners with lower exposure to unemployment risk, but, because singles are unaffected, not necessarily a change in the number of marriages.Footnote 17 This is consistent with the development depicted in Fig. 1, which shows that the overall marriage rate has been constant between 1997 and 2013. However, intermarriage rates plummet during times of high unemployment, suggesting that foreign partners are substituted with German partners when concerns about unemployment rise. The model rationalizes this development through a falling marital surplus of intermarriages relative to marriages among Germans.

Other elements of the Hartz reforms that affected, e.g., labor demand (Hartz I/II) and matching efficiency (Hartz III) treated, in principle, both couples and singles equally. The reason is that these policy changes applied to all individuals irrespective of their marital status. What we cannot rule out, however, is that, say, married individuals are over-represented in the treatment groups of certain reform elements, which could imply that these policy changes are more relevant for couples than for singles. We abstract from this possibility in the present paper because we do not observe the employment status in our primary data source, the marriage register, so we cannot condition marital surplus on the employment status.

The Hartz IV reform, which further reduced the generosity of the UI system and specifically the level of long-term benefits, potentially changed marital surplus. On the one hand, the insurance value of the partner’s income rises if expected transfer income falls, so surplus could rise. On the other hand, only the gains of marriage for the spouse with the higher unemployment risk increase. The gains for the less-at-risk spouse, who has to insure a more volatile income stream, fall, and this is reinforced by means testing.Footnote 18 Figure 1 suggests that the overall marriage rate has not changed around Hartz IV. Moreover, as we show below, the estimated marital surplus in the groups we consider either falls or stays flat. Thus, the theoretically possible positive effect of a UI generosity reduction on marital surplus appears negligible in our setting.

Note also that in the empirical model developed below, any reform effect on selection into marriage that effects all nationalities will be captured by time fixed effects. Similarly, time-constant differences between natives and non-natives are captured by nationality fixed effects. Thus, our empirical model captures all reform effects on intermarriages. Accordingly, a conservative interpretation of our results would be that we capture the total reform effect, and not just the effect of the Hartz I means testing reform, for which the matching model’s predictions are clear-cut.

The EU expansion in 2004 is another event that potentially affected the marriage market. Before the expansion, marriage was one way to obtain the right to live and work in Germany. After the EU expansion, EU10 citizens obtained these right automatically (with initial restrictions). Thus, intermarriage became less attractive for EU10 citizens due to lower gains from marrying Germans. Additionally, their value of singlehood increased because the new rights were granted independently of marital status. Thus, through the lens of the model, the EU expansion also implies lower surplus and falling intermarriage rates, but this effect is reinforced by an increasing value of singlehood. Thus, we expect a bigger effect on marital surplus compared to the labor market reform, and potentially also an increase in the affected single population.

To sum up, the theory suggests that both the Hartz I labor market reform and the EU expansion had a negative effect on the surplus of intermarriages, and additionally, the EU expansion increased the value of singlehood for affected individuals. We test these implications empirically in Section 5, along with a number of robustness checks related to the construction of marital surplus, our model-based outcome variable.

4 Data

4.1 Marriage and divorce registers

The marriage and divorce registers, referred to as MR and DR in the following, cover all marriages and divorces in Germany. These registers originate from the German civil registry offices and divorce courts, respectively.Footnote 19 Both data sources contain information on legally registered marriages of different-sex couples. We have access to the registers for the periods 1991–2013 (MR) and 1995–2013 (DR). A few federal states did not report data prior to 1997, so we discard earlier years. We clean the data by removing duplicates, observations where important variables are missing, and marriages formed outside Germany.Footnote 20 Moreover, we exclude marriages in which one of the individuals’ birth date implies an age below 18. Both data sets are organized at the couple level and contain information on the birth dates of both spouses, the date of marriage, and, in the DR, the date of divorce. Additionally, the data contain various covariates including citizenship of both spouses, religion, place of residence, number of children (before marriage and at the time of divorce), who filed for divorce, and the ruling of the court. We do not observe education, income, or other indicators of socio-economic status.

To estimate marital surplus based on the Choo and Siow (2006) model, we combine the flow of new marriages from the MR data with single stocks by nationality and age group from the German Microcensus (described below). We can merge these single stocks with the MR data only for cells in which the number of observations is sufficiently large. Thus, we use seven (groups of) nationalities: Germany, EU15 (excluding Germany), Poland, Turkey, EU10 (excluding Poland), former Yugoslavia, and “Rest of the World” (residual category). We use six age groups: 18–25, 26–32, 33–39, 40–46, 47–54, and 55–68.

German data protection legislation forbids merging the MR and DR registers at the level of the individual couple. To study marital stability in Section 6, we link both registers by counting observations in cells formed by the quarter of marriage and both spouses’ nationalities. We merge both data sets at this level and “unpack” the linked data-set into individual marriage spells. This allows us to estimate the divorce hazard for different types of marriages formed before and after the law changes.

4.2 The German Microcensus

The German Microcensus (MC) is an annual representative survey that samples 1% of all persons legally residing in Germany.Footnote 21 We select all individuals between 18 and 68 years of age who live in private households. For the period after German reunification (1993–2013), this sample represents a roughly constant population of about 53 million individuals, of which 47% are male.Footnote 22 72% of men and 64% of women are married. To calculate the single stocks by age and nationality, we include all non-married individuals (never-married, divorced, widowed). The MC allows us to distinguish between non-married individuals with and without cohabiting partners, and we exclude cohabiting individuals from the analysis.

The implementation of the MC survey changed from a fixed reference week to continuous interviews over the course of the year in 2005. For the first couple of years, this led to irregularities in the sampling procedure. To make sure that our findings are not affected by this change, we interpolate single stocks for the years 2005–2009. Our findings do neither depend on whether or not we interpolate, nor on the specific technique used.Footnote 23

We interpret Germany as one big marriage market and, thus, compute the single stocks at the national level. While there is substantial variation in the foreign population share across German regions, this strategy has two advantages. First, the sampling error in the MC is not amplified by extrapolating very small numbers of foreign individuals in some regions to the population level using weights. Second, we ensure that we have large enough numbers of observations to merge the MC and MR data without violating German data protection regulation.

4.3 Descriptive evidence

Table 2 presents the distribution of nationalities in all new marriages between 1997 and 2013 for men and women, respectively. We observe a total of 6,626,086 marriages. Roughly 6 million of these marriages have at least one spouse with German nationality. The largest groups of non-Germans who get married in Germany are citizens of the other EU15 member states, Turkish men, and Polish women. Interestingly, the numbers of Turkish women and Polish men, respectively, are much smaller. For most nationalities, the foreign spouse is more often the wife. Exceptions are the EU15 countries and Turkey, for which the number of foreign husbands is higher. Marriages in which at least one spouse is from a different country (“Rest of the World”) also make up a significant share of all observed marriages in Germany.

Table 3 provides a closer look by showing numbers of observations, mean ages, and the mean age difference for all combinations of the four big (groups of) nationalities: German, EU15, Polish, and Turkish. Marriages in which both spouses are foreign citizens are relatively rare. They constitute less than 1% of the total number of marriages for the subsample in Table 3. 0.36% are marriages among Turks and 0.37% are marriages among EU15 citizens (not necessarily the same nationality).Footnote 24

In 8.2% of all marriages, one spouse is German and the other spouse is a foreign citizen. This is the time average of the intermarriage rate in our sample. There are more marriages between German women and foreign men than there are between German men and foreign women. To accommodate the gender asymmetry in our empirical analysis, we later present results for marriages in which the German spouse is either the man or the woman separately, along with a pooled baseline sample.

Age differences between men and women are almost always positive, that is, the husband is usually older. Compared to German-German couples, the age difference is bigger when German men marry non-German women. In case the wife is Turkish, both spouses are significantly younger. Conversely, German women who marry non-German men are on average younger compared to German-German couples, and again much younger if the husband is Turkish. The only case with a (slightly) negative average age difference is couples of EU15 women and Polish men, but this is a very small group. The largest average age differences exist between Polish women and German or EU15 men. In these marriages, the woman is on average more than 6 years younger than the man. This is more than twice the average age gap in German-German couples. To take into account the differences in the age structure across different couple types, our regression models include fixed effects for both the wife’s and the husband’s age group.

5 Reform effects on marital surplus

5.1 (Pre-)trends of marital surplus

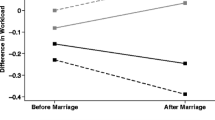

Figure 2 depicts how the estimated marital surplus according to equation (1), denoted \(\hat{\Phi }\), changes over time. We plot the surplus for marriages where at least one spouse, either the wife or the husband, is German, and aggregate nationalities into four groups: German-German marriages (black), German-EU15 marriages (blue), German-EU10 marriages (orange), and German-Other marriages (gray) in which the non-German spouse has any of the remaining nationalities (Turkey, former Yugoslavia, Rest of the World). Figure C.1 in the Online Appendix shows two versions of the same plot in which we condition on the gender of the German spouse.

The visible ranking of marital surplus for different couples reflects, according to the model, differences in the gains from marriage. On the one hand, factors like cultural distance or (gender-specific) preferences tend to lower marital surplus relative to German-German couples.Footnote 25 On the other hand, if access to the labor market is gained by marrying a German citizen, marital surplus tends to be higher, see the surplus difference between German-EU15 and German-EU10 marriages before the EU expansion. Interestingly, this is driven by German husbands with EU-10/other wives, see Fig. C.1. Over time, as EU10 citizens earned the right to live and (later) work in Germany, the surplus converged and eventually the ranking even changed.Footnote 26 Although the surplus falls for marriages with both EU10 and “other” spouses after 2003—according to our main hypothesis as a result of the labor market reform—the “other” line remains above the EU15 line. This is consistent with the idea that spouses from non-EU countries still earn labor market access by marrying a German citizen and thus enjoy higher gains from marriage.

Development of marital surplus (\(\hat{\Phi }\)) over time. Notes: Marriage surplus for marriages where at least one spouse is German by nationality of the non-German spouse. Single stocks based on piecewise cubic Hermite interpolation. The black dashed vertical line indicated the year in which the Hartz I and IV reforms became effective, the red dashed vertical line marks the year 2004 in which the EU expansion took place. Data source: RDC of the Federal Statistical Office and Statistical Offices of the Federal States, Marriage Register and Microcensus, 1997–2013, own calculations

From 1997 until the implementation of the Hartz I labor market reform (black dashed line), the marital surplus evolves in parallel for all nationality combinations and is essentially flat. After 2003, the trends notably diverge. While the surplus for German-German and German-EU15 marriages remains flat, we observe a decline for marriages in which one spouse has EU10 or “other” citizenship. Recall that according to our model, changes in marital surplus reflect deviations from a constant relationship between the single populations and the flow of new marriages. The falling surplus we observe for German-EU10 and German-Other marriages therefore reflects “too few” new marriages relative to the single stocks in the respective groups, which is consistent with the falling intermarriage rates shown in Fig. 1.Footnote 27

The lack of new marriages in these groups after the reform is, according to our main hypothesis, due to the relatively high unemployment risk that these households face. Following the tightening of the means-testing regulations, marriages in which one spouse had a foreign nationality and, thus, on average a higher unemployment risk (see Section 2), required more insurance from the partner and, thus, became less attractive.

In the aftermath of the Hartz I reform, the negative trend in marital surplus for German-EU10 and German-Other marriages appears to be unaffected by the EU expansion (red dashed line) and the Hartz IV reform (blue dashed line). The surplus of German-German and German-EU15 marriages remains flat around the same two law changes. After 2008, the German-Other surplus stabilizes while the German-EU10 continues to fall. This divergence can be explained by the fact that EU10 citizens gradually gained labor market access in Germany while citizens from “other” (i.e., third) countries still needed a German spouse to be allowed to work.

5.2 Empirical setup

We are now in a position to estimate the effect of the Hartz I labor market reform on marital surplus. We use a differences-in-differences specification to identify the effect of the reform on the treated population. We restrict attention to marriages in which at least one spouse is German and define treatment and control groups as illustrated in Table 4. In line with the trends presented in Fig. 2, German-German and German-EU15 marriages are the control group. We verify the composition of the control group in Section 5.4. All other intermarriages form the treatment group for estimating the labor market reform effect. We are able to separately identify the effects of the labor market reform and the EU expansion because couples with an EU10-spouse were treated by both reforms while couples in which the spouse has another foreign nationality (i.e., not EU10 or EU15) were treated by the labor market reform only.

To capture the labor market reform effect, we define a dummy variable \(Treat_{Hartz I}\) that takes on the value 1 for marriages where the non-native partner has one of the following citizenships: EU10, Turkish, former Yugoslavia, Rest of the World. The indicator function \(\mathbbm {1}\{t\ge 2003\}\) returns the value 1 for marriages formed after January 1, 2003, the enactment date of the reform. It follows that our empirical specification to estimate the effect of the labor market reform has the following form:

where one coefficient of interest is \(\beta _3\). It represents the treatment effect on the treated of the Hartz I labor market reform. \(n_m\) and \(n_f\) are the nationality of the male (husband) and female (wife). \(a_m\) and \(a_f\) are the age of the male (husband) and female (wife). The year fixed effect, \(\eta _t\), controls for time trends. The fixed effect for the foreign spouse’s nationality, \(\delta _c\), controls for any confounding factors specific to intermarriages with particular nationalities. This takes care of any unobserved time-invariant determinants of marital surplus. The outcome, \(\hat{\Phi }_t(n_m, n_f, a_m, a_f)\), is the marital surplus for a particular combination of age and country of origin for both partners in year t. In all regressions, we also include the effect of the EU expansion in 2004. The treatment dummy \(Treat_{EU}(n_m, n_f)\) takes on the value 1 for marriages in which the non-native partner has EU10 citizenship. The interaction \(Treat_{EU}(n_m, n_f) \cdot \mathbbm {1}\{t\ge 2004\}\) captures the treatment effect on the treated of the EU expansion and \(\beta _6\) is the respective coefficient of interest.Footnote 28 Lastly, \(u_t(n_m, n_f, a_m, a_f)\) is the residual. We estimate equation (2) by weighted least squares (WLS) and use the observation numbers per age-nationality cells as weights.

5.3 Main results

We present estimation results for multiple specifications in Table 5. Columns (1) and (2) include all marriages where at least one spouse is German. Columns (3) and (4) condition on the husband being German and columns (5) and (6) condition on the wife being German, respectively. Columns (1), (3), and (5) include fixed effects for the year and the nationality of the non-German spouse, so these specifications correspond exactly to equation (2). The specifications that lead to the results shown in columns (2), (4), and (6) additionally include fixed effects for the age (group) of both spouses.

Overall, the labor market reform had a significant and sizable negative effect on the surplus of intermarriages in which the foreign spouse has a non-EU15 citizenship. The estimated coefficient \(\hat{\beta }_3\) is negative and highly significant in all specifications. Robust standard errors are reported in parentheses.Footnote 29 Specification (1) finds a 0.323 log point decrease in the surplus of treated marriages. That is, relative to the 1997–2002 average for marriages between a German and a EU10 (other) spouse, marital surplus decreased by 4.2% (5.2%). Including age fixed effects for husband and wife in specification (2) leads to a slightly larger decrease of 0.410 log points or 5.2% (EU10) and 6.6% (other).

When we condition the estimation on either the wife or the husband being German, we see that the negative effects are bigger for marriages with German wives as compared to German husbands. We find a maximum decline of 0.459 log points in specification (6), which corresponds to a surplus reduction of 7.6% (EU10) or 7.3% (other). In specification (4), the negative impact is 0.398 log-points or 6.4% (EU10) and 8.0% (other). One possible explanation for the asymmetric impact across genders could be that marriages in which the husband is more exposed to labor market risk are generally more vulnerable. Labor force participation and income is on average lower for women in Germany, which is at least partly due to strong and persistent gender norms (Bauernschuster and Rainer 2012; Lippmann et al. 2020).

Overall, we find that the Hartz I reform significantly reduced the surplus, and, thus, the relative attractiveness of intermarriage in Germany. Under the assumptions of the Choo and Siow (2006) model, our estimates represent causal effects. Our hypothesis that the Hartz I labor market reform had significant repercussions in the marriage market is confirmed, and this is of interest for at least two reasons. First, it is conceivable that policy-makers did not intend to affect the marriage market with a reform that was primarily designed to reduce unemployment. Second, intermarriages are often viewed as a vehicle for the integration of ethnic minorities and immigrants (Azzolini and Guetto 2017; Adda et al. 2022). Living with natives can improve labor market access, e.g., by providing additional incentives to learn the language or through access to labor market networks. By negatively affecting intermarriage rates, the labor market reform potentially hampered the integration of the foreign-born population in Germany.

Next, we turn to the effect of the EU expansion on marital surplus. To see how we capture it, recall Table 4 and Equation (2): we compare intermarriages in which the non-native spouse is from a country that joined the EU in 2004 (EU10) with intermarriages in which the non-native spouse is from a country unaffected by the EU expansion (Turkey, former Yugoslavia, Rest of the World). Thus, the treatment dummy \(Treat_{EU}(n_m, n_f)\) takes on the value 1 for marriages in which the non-native partner has EU10 citizenship. The interaction \(Treat_{EU}(n_m, n_f) \cdot \mathbbm {1}\{t\ge 2004\}\) captures the treatment effect on the treated of the EU expansion and \(\beta _6\) is the respective coefficient of interest.Footnote 30

Our estimates of \(\beta _6\) are included in Table 5, again separately for all marriages, marriages with German husbands, and marriages with German wives. In line with our theoretical prediction and similar to the Italian case discussed in Adda et al. (2022), we find negative and significant effects of the EU expansion on the marital surplus of German-EU10 marriages. Similar to the labor market reform, the effect is larger for intermarriages with German wives. This suggests that the right to live and work in Germany was valued more highly by males from EU10 countries than by females from the same countries prior to the expansion. The point estimates are larger than those for the labor market reform. This confirms our conjecture that the EU expansion had a larger negative effect on the marital surplus because the value of singlehood increased. Recall that the means testing reform did not affect the value of singlehood.

Our finding that the EU expansion affected the German marriage market corroborates the results of Adda et al. (2022) for Italy because Germany has a different institutional background and migration history. First, Germany initially restricted labor market access for citizens of the new member states. Second, Germany has been receiving migrants longer than Italy and intermarriage is relatively common.Footnote 31 Still, the EU expansion has affected the marriage market in similar ways in both countries.

5.4 Robustness checks

We argue that the reduction of marital surplus reflects fewer marriages between Germans and foreigners (recall Fig. 1). We ascribe this trend to, on the one hand, higher exposure to unemployment risk when faced with stricter means testing and, on the other hand, more rights for EU10 citizens after the expansion. However, according to the Choo and Siow (2006) model, the flow of marriages can only be interpreted relative to the number of available singles.Footnote 32 Therefore, we scrutinize further the role that the single stocks play for our findings. First, we check how restrictive it is to compute the marital surplus based on the contemporaneous single stocks, which is what the static Choo and Siow (2006) model suggests. Second, we analyze to what extent the single stocks have changed over time. Third, we revisit the composition of our treatment and control groups.

In the static Choo and Siow (2006) model, only the contemporaneous single stocks matter for the marital surplus. In reality, however, partnership formation takes time. Individuals often live together for years before getting formally married. Moreover, we use the flow of new marriages to construct marital surplus, which could in principle depend on the available singles in previous periods. Thus, an observed marriage in a given period could depend on decisions made earlier, and at this earlier point in time the availability of potential partners may have been different. To evaluate whether our results are sensitive to the way the marital surplus is specified, we recalculate the surplus based on single stocks from up to 3 years earlier, and then re-estimate our main specifications. The results are presented in Table 6.

Panels A, B, and C show results where we replace the year t single stocks \(\mu (m_{a, n}, 0)_t\) and \(\mu (0,f_{a, n})_t\) with the respective values for \(t-1\), \(t-2\), and \(t-3\). Columns (1), (4), and (7) are directly comparable to our baseline specification with age dummies in Table 5. Reassuringly, effect sizes and significance levels remain fairly unaffected by the change. The gender differences discussed in the context of Table 5 are no longer visible, but overall none of our substantive conclusions changes when using lagged single stocks. In columns (2), (5), and (8), we additionally add the contemporaneous single stock for both genders as a control. In this case, the effect is again larger for intermarriages with German wives. Adding the lagged single stock (same lag as used for the construction of the marital surplus) as a control instead does not change the picture, see columns (3), (6), and (9). Overall, these alternative specifications do not challenge our results. We find these consistent and significant patterns reassuring with respect to the conclusions we have drawn so far.

Next, we consider the time dynamics of the single stocks. Our main finding, the reduced marital surplus for intermarriages, would also be consistent with an increasing number of singles in the same groups and a constant flow of (inter)marriages. The EU expansion is one reason to expect increased migration flows into Germany, that is, the number of non-German singles could have increased. We check whether the single stocks responded to either the EU expansion or the labor market reform by repeating our regression analysis with the single stocks instead of the marital surplus as the outcome variable. The results are presented in Online Appendix Table C.2, along with further details on these specifications.

Reassuringly, the single stocks have not changed systematically in response to either of the reforms. Specifically, the EU expansion did not lead to more singles in the EU10 group relative to the untreated nationalities. The point estimate for the labor market reform is larger and, as one might expect, negative. But statistically it is indistinguishable from zero. Moreover, the included time dummies do not suggest a general trend in the single stocks. Overall, these results are consistent with the flat overall marriage rate (recall Fig. 1) and the aforementioned fact that Germany had a sizable but stable migrant population during the period we consider. We conclude that our main results are not driven by the time dynamics of the single stocks.

As a final robustness check, we revisit the composition of our treatment and control groups. In the main analysis, we use marriages formed between two Germans and Germans with members of an EU15 country as the control group. This choice is supported by the trends in Fig. 2. Moreover, from a legal perspective, employers are not allowed to discriminate between native Germans and members of the EU15 countries, which might explain why the attractiveness of EU15 partners has not been negatively affected by the labor market reform. Still, the EU15 group includes a diverse group of foreigners and, thus, could mask important heterogeneity.

To open this black box, we exploit differences between the German language and the languages spoken in the remaining EU15 countries. The idea is that speaking a Germanic language facilitates labor market access for foreign-born individuals (Dustmann 2003; Aldashev et al. 2009; Wong 2023). Thus, it could lower the exposure to unemployment risk and make individuals from countries with Germanic languages more attractive from the risk-sharing perspective. To operationalize this idea in the data, we separate the EU15 countries into “linguistically close” (Belgium, Denmark, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Austria, Sweden) and “linguistically distant” (Finland, France, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal, Spain, the UK) countries relative to Germany.

Figure C.2 in the Online Appendix shows the development of marital surplus between Germans and EU15 nationals when the EU15 group is separated by linguistic distance.Footnote 33 As before, German-EU10 and German-Other marriages experience a fall in surplus after 2003 but the surplus of German-German, German-EU15 (close), and German-EU15 (distant) marriages remains stable over time. One could have suspected that marriages in which the non-German spouse is from a EU15 (distant) country are also (partly) treated due to, on average, lower language skills and labor market attachment. This does not appear to be the case, and this validates our decision to include both German-German and all German-EU15 marriages in the control group.

To further investigate the language channel, we repeat our main analysis with four different sets of treatment and control groups. First, we re-estimate our baseline model using EU15 (close) and EU15 (distant) as two separate control groups. Given that we use weighted (by the number of marriages per cell) OLS, the results should be unaffected by this. Indeed, the results reported in panel A of Table 7 are virtually identical to our baseline results. Next, we estimate the model using German-German and German-EU15 (close) marriages as the only control group.Footnote 34 The coefficients for the labor market reform effect are reported in panel B of Table 7. They decrease in size but remain significant and quantitatively important throughout all but one specification. We also test the counterintuitive case in which only German-German and German-EU15 (distant) marriages are the control group (panel C). Again, we get very similar and significant estimates. Lastly, we restrict the sample to include German-German, German-EU15 (close), and German-EU15 (distant) marriages only. We estimate the effect of interest using German-German marriages as the only control group. Essentially, this is a falsification test. If we did find significant effects, there would be significant treatment differences within the control group of the baseline specification. Reassuringly, the estimated coefficients become small and insignificant, see panel D of Table 7.

6 Reform effects on marital stability

In the final step of the analysis, we use the German divorce register (DR) to compare the stability of marriages formed before and after the two law changes. As explained in Section 4, we combine the marriage and divorce registers at the quarter of marriage-nationality-nationality level to study the survival of different types of marriages.

Our results so far show that the declining marital surplus after the labor market reform is a reflection of fewer new intermarriages. We conjecture that the remaining intermarriages—the ones that are formed after 2003 despite the reforms—are positively selected compared to intermarriages formed before the reform. The reason is that these couples were aware of the reduced generosity of the unemployment insurance system when they got married, while pre-reform couples based their decision to get married on a more generous UI system. Thus, we expect that post-reform marriages are more stable, i.e., have a lower divorce probability. One reason could be a higher ability to absorb economic shocks—precisely because post-reform couples expected to insure each other against income shocks at the time of marriage.

For the EU expansion, the expected effect on marital stability goes in the same direction but the mechanism is different. For German-EU10 marriages formed after the expansion, gaining the right to live and work in Germany is no longer part of the surplus. Couples that form despite this negative surplus change are likely positively selected. This effect is reinforced by the increased value of singlehood for EU10 citizens in Germany.

To test these conjectures, we re-apply our differences-in-differences estimation strategy in a Cox proportional-hazard framework (Cox 1972). In our application, the baseline hazard is that of a marriage of two individuals who are both neither affected by the labor market reform, nor the EU expansion. As before, this applies to marriages between natives and citizens of EU15 member states. The coefficients of interest are again the ones associated with the treatment dummy interactions \(Treat_{Hartz I}(n_m, n_f) \cdot \mathbbm {1}\{t\ge 2003\}\) for the labor market reform and \(Treat_{EU}(n_m, n_f) \cdot \mathbbm {1}\{t\ge 2004\}\) for the EU expansion. That is, we compare the stability of marriages in which one partner is of a treated nationality before and after the respective law change.

We either stratify by divorce year or include fixed effects to control for influences specific to the year of divorce. When stratifying by divorce year, one allows for different baseline hazards for every single divorce year. This is tantamount to assuming that all divorcing couples in a given year are exposed to the same environment, e.g., the same aggregate labor market situation and legal framework.Footnote 35

The results are presented in Table 8, separately for all marriages, marriages with German husbands, and marriages with German wives. Column (1) shows the results in the full sample without taking divorce year effects into account. The estimated coefficient of \(Treat_{Hartz I}(c_h, c_w) \cdot \mathbbm {1}\{t\ge 2003\}\) indicates that the divorce hazard increased by 9.3% for marriages treated by the labor market reform. This would suggest that the labor market reform lowered marital stability, which is not in line with the expected selection effect. However, the sign of the effect flips in columns (2) and (3) where divorce year effects are taken into account. In both specifications, we find significant and sizable negative effects of the labor market reform on the divorce hazard that range from 26.4 to 36.6% relative to the baseline. In other words, marriages with one spouse from a non-EU15 country became more stable after the reform, in line with positive selection. We confirm the same trends for the sub-samples of marriages where the husband is German and where the wife is German. There is always a large reduction of the divorce hazards once we control for year fixed effects or stratify by divorce year. We see no clear difference in the effect sizes for couples with German husbands and wives in this case.

The EU expansion had a further stabilizing effect on the (remaining) marriages between Germans and citizens of the new member states. The effect is slightly larger than the effect of the Hartz I labor market reform, which is again in line with the additional effect through the value of singlehood. The effect of the EU expansion is larger for marriages with German husbands as compared to German wives. This might be due to the fact that marriages between German women and EU10 men are relatively rare. Interestingly, the effect of the labor market reform is substantially larger than the effect of the EU expansion for intermarriages with German wives. This can be rationalized with a male-breadwinner norm. In this case, the labor market reform should have a stronger effect on the partner selection of women. Thus, intermarriages with German wives that formed despite the labor market reform are likely to be particularly well-selected.

7 Conclusion

In this paper, we empirically investigate the importance of within-household insurance for marriage formation and stability. Exploiting a sharp generosity reduction in the German unemployment insurance system—stricter means testing, which started with the Hartz I reform in 2003—we find that marriages in which one partner had an elevated unemployment risk, proxied by nationality, became significantly less attractive. Provided that both our identifying assumption linking unemployment risk to nationality and the assumptions underlying the Choo and Siow (2006) model hold, the estimated reform effect on marital surplus can be interpreted as causal.

Furthermore, we provide external validity to the study by Adda et al. (2022), who investigate the effect of the EU expansion in Italy. Even in a different institutional setting and conditional on the earlier labor market reform, we find a significant negative effect of the EU expansion on marital surplus for the affected nationalities. However, the EU expansion only affected a fraction of Germany’s relatively large and diverse migrant population. Overall, the labor market reform had a larger impact. Moreover, we find that intermarriages formed after the two reforms are significantly more stable than those formed before. Our interpretation is that the law changes resulted in fewer, but better selected intermarriages.

The significant and quantitatively important negative effect on the marital surplus of intermarriages in Germany is a finding of high policy relevance. The marriage market ramifications of the labor market reform were probably not intended by the policy-maker. Moreover, intermarriage is often seen as an indicator for the successful integration of migrants. Social security reforms that make intermarriage less attractive may therefore interfere with the integration of migrants and have negative long-run effects.

Availability of data and materials

The empirical analysis in this paper is based on German register data, which are not publicly available. Interested researchers can get access to the data used in this paper through the Research Data Centres of the German Federal States and the German Federal Employment Agency. The paper includes a detailed description of the data and our cleaning procedures. Programs are available upon request.

Change history

24 July 2023

Missing Electronic Supplementary Material has been added.

Notes

In a recent paper, Wang (2019) studies joint job search decisions of couples in a life-cycle model with risk sharing. Using US micro data, she finds that gender differences in the cyclicality of unemployment can be explained by household-level risk sharing.

At the macro level, a common finding is that marriage and divorce rates are pro-cyclical, that is, they decrease in recessions. Correlations with the unemployment rate are typically negative (Amato and Beattie 2011; Hellerstein and Morrill 2011; Schaller 2013; González-Val and Marcén 2017a, b). At the micro level, Jensen and Smith (1990) and Hansen (2005) find that unemployment affects marital stability using Danish and Norwegian register data.

Note that our definition is based on citizenship and not ethnicity. In related research, Caucutt et al. (2018) use a comparable empirical design to investigate to what extent racial differences in marriage market outcomes in the USA are explained by high unemployment and incarceration rates of black men.

In 2004, Cyprus, Malta, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia, and Slovenia joined the EU. We refer to this group of countries as EU10. Before the expansion, the EU had 15 member states referred to as EU15: Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, the UK.

The exemption was proportional to the partner’s age. Before the reform, the amount was 520 Euros per year of the partner’s age (maximum of 33,800 Euros at age 65). This amount decreased to 200 Euros per year of the partner’s age.

We cannot rule out that other reform elements also affected couples and singles differentially because either married or single individuals could be over-represented in the treatment groups of specific reform elements. If these effects are quantitatively important, our estimator will capture the total reform effect.

We use the factually anonymous Sample of Integrated Labor Market Biographies (File: SIAB_7514) Data access is provided by the Research Data Center (RDC) of the German Federal Employment Agency (BA) at the IAB, project no. 101693. See Ganzer et al. (2016) for more details on the data set.

1997 is the first year for which the marriage and divorce registers are available. To avoid capturing reform effects on unemployment risk, we exclude all years after 2002.

The education variable in German social security data suffers from missing values and inconsistencies because misreporting has no negative consequences. We impute missing and inconsistent observations following Fitzenberger et al. (2006). We use five levels of education: lower secondary education without/with vocational training, higher secondary education without/with vocational training, and tertiary education (University, University of Applied Sciences). The distribution of German and foreign men and women across educational categories is shown in Online Appendix Table C.1.

We use six age groups: 18–25, 26–32, 33–39, 40–46, 47–54, and 55–68.

The model also incorporates unobserved heterogeneity, which affects marital surplus quasi-additively and is i.i.d. following a standard type I extreme value distribution. See Online Appendix A for details.

Through the lens of the model, only the relative attractiveness of different partner types changes. See Online Appendix equation (A.3): after the reform, a different \(V_{ijg}\) delivers the highest attainable utility, but \(V_{i0g}\) and \(V_{0jg}\) remain unchanged.

Note that Hartz IV tightened means testing further because long-term unemployment benefits were abolished and the lower social benefits do not have a means testing exemption.

Data access is provided through the statistical offices of the German federal states.

Marriages formed outside Germany were not recorded before 2008 and represent only 0.15% of all marriages thereafter.

Data access is provided by the research data centers of the statistical offices of the German federal states. The survey program of the MC consists of a set of core questions that remains the same in each wave, covering general demographic and socioeconomic characteristics like marital status, education, employment status, individual and household income, among many other things.

Extrapolated from information on 8,426,756 surveyed individuals using sample weights. The average number of observations per wave is 443,513.

See Online Appendix B and Statistisches Bundesamt (2012) for details. For our baseline results, we rely on a piecewise cubic Hermite interpolation. Results for different interpolations are available upon request.

Due to the small number of marriages without any German spouse, and because marriages among foreign nationals may not show up in the German marriage registers (married abroad), we restrict our main analysis to marriages where at least one spouse is German.

In Section 5.3, we control for such time-invariant differences by using nationality fixed effects.

Again, this is driven by marriages between German men and EU-10 women. The marital surplus for German women and EU-10 men is the lowest overall, see Fig. C.1a.

Fewer new marriages in the respective groups could reflect a substitution of marriage with cohabitation. To check this, we calculate the cohabitation rate, which we define as the population share of individuals who are unmarried and cohabit with their partner (with or without children), using MC data. The slow but steady trend towards more cohabitation is in fact interrupted in 2004 and 2005 and the rate even falls by 0.1 percentage points in 2006. Thus, the missing marriages are not replaced by more cohabiting couples.

We focus on the 2004 EU expansion. Romania joined the EU later and is thus not in the treatment group but in the “Rest of World”-category.

Clustered standard errors (by year, unreported) do not affect the significance of our estimated coefficients. To interpret our findings conservatively, we report the larger robust standard errors throughout the paper.

Note that we define the indicator function \(\mathbbm {1}\{t\ge 2004\}\) such that it returns 1 for all marriages formed after January 1 2004 although the new member states joined the EU only on May 1, 2004. This is necessary because MC single stocks are only available on an annual basis.

According to Adda et al. (2022), the share of foreign residents in Italy was below 2% during the 1990s and only started to increase in the 2000s. It reached around 9% in 2013. In contrast, migrants have been flowing into Germany since the 1950s/1960s. The share of residents without German citizenship was stable at around 8–9% of the population during the period we study (Federal Statistical Office). In 1997, about 10% of all marriages in Germany were intermarriages. In contrast, Adda et al. (2022) report 3% intermarriages for Italian men and around 1% for Italian women in 1996.

Ceteris paribus, an increase in the number of available singles implies a proportionate increase in the number of marriages. A lack of new marriages for a given single stock implies a deviation from the constant relationship and, therefore, falling marital surplus.

Interestingly, the marriage surplus of DE-EU10 marriages converges to the surplus of DE-EU15 (close) marriages over time (as the initial labor market restrictions for EU10 citizens become less binding). Thus, in terms of marital surplus with a German citizen, EU10 nationals are more comparable to EU15 (close) than to EU-15 (distant) citizens. This can be explained with the close historic ties between Germany and the Eastern European EU10 countries, for example due to the influence of the Prussian and Austro-Hungarian Empires in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

A detailed overview over the treatment and control groups we use for this exercise is provided in Table C.3 in the Online Appendix.

In contrast, stratification by marriage year would assume that all couples married in a given year face the same baseline hazard, which seems hard to defend.

References

Adda J, Pinotti P, Tura G (2022) There’s more to marriage than love: the effect of legal status and cultural distance on intermarriages and separations. unpublished

Aiyagari SR (1994) Uninsured idiosyncratic risk and aggregate saving. Q J Econ 109(3):659–684

Aldashev A, Gernandt J, Thomsen SL (2009) Language usage, participation, employment and earnings: evidence for foreigners in West Germany with multiple sources of selection. Labour Econ 16(3):330–341

Amato PR, Beattie B (2011) Does the unemployment rate affect the divorce rate? An analysis of state data 1960–2005. Soc Sci Res 40(3):705–715

Anderberg D, Bagger J, Bhaskar V, et al (2020) Marriage market equilibrium with matching on latent ability: identification using a compulsory schooling expansion. unpublished

Azzolini D, Guetto R (2017) The impact of citizenship on intermarriage: quasi-experimental evidence from two European Union Eastern enlargements. Demogr Res 36:1299–1336

Basu S (2015) Intermarriage and the labor market outcomes of Asian women. Econ Inq 53(4):1718–1734

Bauernschuster S, Rainer H (2012) Political regimes and the family: how sex-role attitudes continue to differ in reunified Germany. J Popul Econ 25(1):5–27

Becker GS (1973) A theory of marriage: part I. J Polit Econ 81(4):813–846

Becker GS (1981) A treatise on the family. Harvard University Press

Blundell RW, Preston I, Walker I et al (1994) The measurement of household welfare. Cambridge University Press

Browning M, Chiappori PA, Lewbel A (2013) Estimating consumption economies of scale, adult equivalence scales, and household bargaining power. Rev Econ Stud 80(4):1267–1303

Caucutt E, Guner N, Rauh C (2018) Is marriage for white people? Incarceration, unemployment, and the racial marriage divide. HCEO Working Paper 2018-074, Human Capital and Economic Opportunity Global Working Group

Chen L, Choo E, Galichon A, et al (2021) Matching function equilibria with partial assignment: existence, uniqueness and estimation

Cherchye L, De Rock B, Lewbel A et al (2015) Sharing rule identification for general collective consumption models. Econometrica 83(5):2001–2041

Chiappori PA, Mazzocco M (2017) Static and intertemporal household decisions. J Econ Lit 55(3):985–1045

Chiappori PA, Reny PJ (2016) Matching to share risk. Theor Econ 11(1):227–251

Chiappori PA, Salanié B, Weiss Y (2017) Partner choice, investment in children, and the marital college premium. Am Econ Rev 107(8):2109–2167

Choo E (2015) Dynamic marriage matching: an empirical framework. Econometrica 83(4):1373–1423

Choo E, Siow A (2006) Who marries whom and why. J Polit Econ 114(1):175–201

Cox DR (1972) Regression models and life-tables. J R Stat Soc Ser B (Methodol) 34(2):187–220

Cullen JB, Gruber J (2000) Does unemployment insurance crowd out spousal labor supply? J Labor Econ 18(3):546–572

Dribe M, Nystedt P (2015) Is there an intermarriage premium for male immigrants? Exogamy and earnings in Sweden 1990–2009. Int Migr Rev 49(1):3–35

Dustmann FChristian; Fabbri (2003) Language proficiency and labour market performance of immigrants in the UK. Econ J 113(489):695–717

Fitzenberger B, Osikominu A, Völter R (2006) Imputation rules to improve the education variable in the IAB employment subsample. Schmollers Jahrbuch J Appl Soc Sci Stud / Z Wirtschafts-und Sozialwissenschaften 126(3):405–436

Furtado D, Theodoropoulos N (2009) I’ll marry you if you get me a job: marital assimilation and immigrant employment rates. Int J Manpow 30(1–2):116–126

Galichon A, Salanié B (2021) Cupid’s invisible hand: social surplus and identification in matching models. Rev Econ Stud 89(5):2600–2629

Ganzer A, Schmucker A, vom Berge P, et al (2016) Sample of integrated labour market biographies regional file 1975-2014 (SIAB-R 7514). FDZ Data report 01/2017, The Research Data Centre (FDZ) at the Institute for Employment Research (IAB), Nürnberg

Gayle GL, Shephard A (2019) Optimal taxation, marriage, home production, and family labor supply. Econometrica 87(1):291–326

González-Val R, Marcén M (2017) Divorce and the business cycle: a cross-country analysis. Rev Econ Househ 15(3):879–904

González-Val R, Marcén M (2017) Unemployment, marriage and divorce. Appl Econ 50(13):1–14

Greenwood J, Guner N, Kocharkov G et al (2016) Technology and the changing family: a unified model of marriage, divorce, educational attainment, and married female labor-force participation. Am Econ J Macroecon 8(1):1–41

Grossbard-Shechtman A (1984) A theory of allocation of time in markets for labour and marriage. Econ J 94(376):863–882

Hansen HT (2005) Unemployment and marital dissolution: a panel data study of Norway. Eur Sociol Rev 21(2):135–148

Hartung B, Jung P, Kuhn M (2022) Unemployment insurance reforms and labor market dynamics. Unpublished

Hellerstein JK, Morrill MS (2011) Booms, busts, and divorce. BE J Econ Anal Policy 11(1)

Jensen P, Smith N (1990) Unemployment and marital dissolution. J Popul Econ 3(3):215–229

Kantarevic J (2005) Interethnic marriages and economic assimilation of immigrants. Discussion Paper 1142, IZA Institute of Labor Economics

Lippmann Q, Georgieff A, Senik C (2020) Undoing gender with institutions: lessons from the German division and reunification. Econ J 130(629):1445–1470

Lise J, Seitz S (2011) Consumption inequality and intra-household allocations. Rev Econ Stud 78(1):328–355

Low H, Meghir C, Pistaferri L, et al (2018) Marriage, labor supply and the dynamics of the social safety net. Working Paper 24356, National Bureau of Economic Research

Lundberg S (1985) The added worker effect. J Labor Econ 3(1, Part 1):11–37

Meng X, Gregory RG (2005) Intermarriage and the economic assimilation of immigrants. J Labor Econ 23(1):135–175

Meng X, Meurs D (2009) Intermarriage, language, and economic assimilation process: a case study of France. Int J Manpow 30(1–2):127–144

Mourifié I (2019) A marriage matching function with flexible spillover and substitution patterns. Econ Theory 67(2):421–461

Muellbauer J (1977) Testing the Barten model of household composition effects and the cost of children. Econ J 87(347):460–487

Ortigueira S, Siassi N (2013) How important is intra-household risk sharing for savings and labor supply? J Monet Econ 60(6):650–666

Persson P (2020) Social insurance and the marriage market. J Polit Econ 128(1):252–300

Pesaran MH, Wickens MR (1999) Handbook of applied econometrics volume I: macroeconomics, vol 1. Blackwell Publishing

Schaller J (2013) For richer, if not for poorer? Marriage and divorce over the business cycle. J Popul Econ 26(3):1007–1033

Shore SH (2010) For better, for worse: intrahousehold risk-sharing over the business cycle. Rev Econ Stat 92(3):536–548

Statistisches Bundesamt (2012) Mikrozensus: Haushaltszahlen ab 2005

Wang H (2019) Intra-household risk sharing and job search over the business cycle. Rev Econ Dyn 34:165–182

Wong L (2023) The effect of linguistic proximity on the labour market outcomes of the asylum population. J Popul Econ 36:609–652

Acknowledgements

This paper supersedes an earlier draft circulated under the title “Marriage and Divorce: The Role of Labor Market Institutions” (CESifo Working Paper No. 8058, August 2020). We thank Natalia Danzer, Timo Hener, Helmut Rainer, Uwe Sunde, editor Terra McKinnish, four anonymous referees, and conference participants at the IZA Workshop on Labor Market Institutions, the EALE/SOLE/ASSLE World Conference, and the DFG SPP 1764 conference on “The German Labor Market in a Globalized World: Trade, Technology, and Demographics” for helpful comments and suggestions. The paper presents results of the ifo Institute’s research project “Economic Uncertainty and the Family” (EcUFam). Both authors gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Leibniz Association (Grant No. SAW-2015-ifo-4). In addition, Bastian Schulz thanks the Aarhus University Research Foundation (Grant No. AUFF-F-2018-7-6), and the Dale T. Mortensen Centre at the Department of Economics and Business Economics, Aarhus University, for funding. Patrick Schulze provided excellent research assistance. We also thank Heiko Bergmann and Karen Meyer, Research Data Centre of the Statistical Offices of the Federal States, for help with data access.

Funding

This work was supported by the Leibniz Association (Grant No. SAW-2015-ifo-4) and the Aarhus University Research Foundation (Grant No. AUFF-F-2018-7-6). Open access funding provided by Vienna University of Economics and Business (WU).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Disclaimer

The content of this paper is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the views of the institutions providing funding or data access.

Additional information

Responsible editor: Terra McKinnish.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Schulz, B., Siuda, F. Marriage and divorce: the role of unemployment insurance. J Popul Econ 36, 2277–2308 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-023-00961-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-023-00961-1

Keywords

- Marriage

- Divorce

- Household risk sharing

- Unemployment insurance

- Labor market reform

- Intermarriage

- EU expansion