Abstract

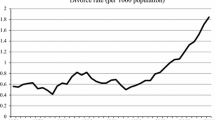

In this paper, we examine the role of the business cycle in divorce. To do so, we use a panel of 29 European countries covering the period from 1991 to 2012. We find the unemployment rate negatively affects the divorce rate, pointing to a pro-cyclical evolution of the divorce rate, even after controlling for socio-economic variables and unobservable characteristics that can vary by country, and/or over time. Results indicate that a one-percentage-point increase in the unemployment rate involves almost 0.025 fewer divorces per thousand inhabitants. The impact is small, representing around 1.2 % of the average divorce rate in Europe during the period considered. Supplementary analysis, developed to explore a possible non-linear pattern, confirms a negative relationship between unemployment and divorce in European countries, with the inverse relationship being more pronounced in those countries with higher divorce rates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

“Hard Times in Spain Force Feuding Couples to Delay Divorce,” The New York Times, http://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/18/world/europe/hard-times-in-spain-force-feuding-couples-to-delay-divorce.html?pagewanted=all&_r=1&.

Due to problems with the availability of data on the divorce rate, we could not include in the analysis the following European countries: Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Georgia, Kosovo, Liechtenstein, Malta, Moldova, Monaco, Montenegro, Russia, San Marino, Serbia, Turkey, and Ukraine. The FYR of Macedonia was also excluded from the analysis, following the suggestions of two anonymous referees, as Macedonia can be considered to be an outlier in this analysis. The unemployment rate of Macedonia is considerably higher (more than twice) than that of the other European countries, with a rate near 30 % in all periods considered, and the divorce rate is half of that in the other countries. In any case, we also repeated the analysis including the FYR of Macedonia, and the results did not change substantially.

Although there may be some concerns about the use of the crude divorce rate, it is worth noting that other papers that contain information about both the crude divorce rate and the total divorce rate did not find differences in their results (see González-Val and Marcén 2012a and Marcén 2015). Those authors showed that both rates behave in the same manner.

The Ireland divorce rate was excluded from that figure because divorce was not allowed in that country until the 1990s. The Family Law Act that regulates divorce was passed in 1996, although the act was not in force until 1997. The rest of the countries introduced divorce many years earlier. All of the analysis presented in this work was repeated without Ireland, and the results did not change.

Robust standard errors clustered by country. All specifications include country fixed effects, year fixed effects, and country-specific linear and quadratic time trends. We repeated all of the analysis with/without all these controls, with/without population weights and with/without clustering the standard errors, and the results did not vary.

In the case of Ireland, data on divorce is only available since 1997 because divorce was not allowed before that date. As mentioned above, our findings do not change when Ireland is excluded from the sample.

It is also arguable that if the number of divorced individuals increases, the demand for housing could also increase when divorcees do not move in with a new partner. In this setting, a rise in the number of divorced individuals could drive changes in unemployment rates through an increase in the number of workers in the building sector. However, changes in the building sector take time because it is not easy to build a new house or building in a few days (projects, licenses are hard to obtain, etc.); thus, an impact of the divorce rate on the contemporaneous unemployment rate would be unlikely. It would be more likely to detect changes in the renting of houses, which normally demands fewer workers than the construction sector. From those arguments, it would be unlikely to observe variations in the contemporaneous unemployment rate caused by changes in the divorce rates, mitigating previous concerns.

We have tested the robustness of all our results to the inclusion of the male unemployment rate and our results are not affected.

We re-ran all of the analysis excluding each country, one at a time, and excluding those countries that exhibit the highest and the lowest unemployment and divorce rates. The results did not change substantially.

No data were available for the whole period in the cases of Croatia, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Slovakia, and Slovenia. For consistency, we repeated the analysis without those countries. The results did not vary.

We recognize that changes in these variables may drive unemployment and divorce rates. Although this issue can be problematic, it is comforting that adding or deleting all of these variables does not affect our conclusions concerning the relationship between divorce and unemployment rates.

Observations are not available for the whole sample. For this reason, we repeated the analysis with only that sample (column (4) of Table 5), and our results are the same.

We have repeated the estimates by including/excluding those countries that introduced reforms related to the separation period during the period considered, and the results are maintained.

We take into account the divorce law reforms that occurred during the period considered to calculate our estimates.

The magnitude of the effect varies a little, especially in the case of joint custody reform, but this result should be interpreted with caution because we are considering all reforms pertaining to joint custody, not only those related to joint physical custody.

This analysis was repeated including more lags. We obtained the same results.

The local polynomial provides a smoother fit for the divorce rate to a polynomial form of the unemployment rate, via locally-weighted least squares. We used the lpolyci command in STATA with the following options: local mean smoothing, a Gaussian kernel function to calculate the locally-weighted polynomial regression, and a bandwidth determined by Silverman’s rule-of-thumb.

Moreover, quantile regressions are invariant to monotonic transformations of the dependent variable, such as logarithms.

References

Alesina, A., Glaeser, E. L., & Sacerdote, B. (2001). Why doesn’t the United States have a European-style welfare state? Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 2001(2), 187–277.

Allen, D. W. (1998). No-fault divorce in Canada: Its cause and effect. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 37, 129–149.

Amato, P. R., & Beattie, B. (2011). Does the unemployment rate affect the divorce rate? An analysis of state data 1960–2005. Social Science Research, 40, 705–715.

Ariizumi, H., Hu, Y., & Schirle, T. (2015). Stand together or alone? Family structure and the business cycle in Canada. Review of Economics of the Household, 13, 135–161.

Baghestani, H., & Malcolm, M. (2014). Marriage, divorce and economic activity in the US: 1960–2008. Applied Economics Letters, 21(8), 528–532.

Bahr, Howard M., & Chadwick, Bruce A. (1985). Religion and family in middletown, USA. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 47(2), 407–414.

Becker, G. S., Landes, E. M., & Michael, R. T. (1977). An economic analysis of marital instability. Journal of Political Economy, 85(6), 1141–1187.

Eckstein, Z., & Lifshitz, O. (2011). Dynamic female labor supply. Econometrica, 79(6), 1675–1726.

Eeckhout, J. (2004). Gibrat’s law for (all) cities. American Economic Review, 94(5), 1429–1451.

Fernández, R., & Wong, J. C. (2014a). Divorce risk, wages and working wives: A quantitative life-cycle analysis of female labour force participation. The Economic Journal, 124(576), 319–358.

Fernández, R., & Wong, J. C. (2014b). Unilateral divorce, the decreasing gender gap, and married women’s labor force participation. American Economic Review, 104(5), 342–347.

Fischer, T., & Liefbroer, A. C. (2006). For richer, for poorer: The impact of macroeconomic conditions on union dissolution rates in the Netherlands 1972–1996. European Sociological Review, 22(5), 519–532.

Friedberg, L. (1998). Did unilateral divorce raise divorce rates? Evidence from panel data. American Economic Review, 88(3), 608–627.

Furtado, D., Marcen, M., & Sevilla-Sanz, A. (2013). Does culture affect divorce? Evidence from European immigrants in the US. Demography, 50(3), 1013–1038.

González, L., & Viitanen, T. K. (2009). The effect of divorce laws on divorce rates in Europe. European Economic Review, 53, 127–138.

González-Val, R., & Marcén, M. (2012a). Unilateral divorce versus child custody and child support in the U.S. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 81(2), 613–643.

González-Val, R., & Marcén, M. (2012b). Breaks in the breaks: An analysis of divorce rates in Europe. International Review of Law and Economics, 32(2), 242–255.

Hellerstein, J. K., & Morrill, M. S. (2011). Booms, busts, and divorce. The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis and Policy, 11(1) (Contributions), Article 54.

Hellerstein, J. K., Morrill, M. S., & Zou, B. (2013). Business cycles and divorce: Evidence from microdata. Economics Letters, 118, 68–70.

Hoynes, H. W., Miller, D. L., & Schaller, J. (2012). Who suffers in recessions and jobless recoveries. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 26(3), 27–48.

Ioannides, Y. M., & Overman, H. G. (2004). Spatial evolution of the US urban system. Journal of Economic Geography, 4(2), 131–156.

Jensen, P., & Smith, N. (1990). Unemployment and marital dissolution. Journal of Population Economics, 3(3), 215–229.

Kirk, D. (1960). The influence of business cycles on marriage and birth rates. In Demographic and economic change in developed countries (pp. 241–260). Columbia University Press. http://www.nber.org/chapters/c2388.pdf.

Koenker, R., & Bassett, G. (1978). Regression quantiles. Econometrica, 46(1), 33–50.

Marcén, M. (2015). Divorce and the birth-control pill in the US, 1950–85. Feminist Economics, 21(4), 151–174.

Nunley, J. M. (2010). Inflation and other aggregate determinants of the trend in US divorce rates since the 1960s. Applied Economics, 42(26), 3367–3381.

Nunley, J. M., & Zietz, J. (2008). The U.S. divorce rate: The 1960s surge versus its long-run determinants. MPRA Working Paper 16317.

Ogburn, W. F., & Thomas, D. S. (1922). The influence of the business cycle on certain social conditions. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 18, 324–340.

Schaller, J. (2013). For richer, if not for poorer? Marriage and divorce over the business cycle. Journal of Population Economics, 26, 1007–1033.

Shore, S. H. (2009). For better, for worse: intra-household risk-sharing over the business cycle. Review of Economics and Statistics, 92(3), 536–548.

South, S. J. (1985). Economic conditions and the divorce rate: A time-series analysis of the postwar United States. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 47, 31–41.

Stevenson, B., & Wolfers, J. (2007). Marriage and divorce: changes and their driving forces. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 21(2), 27–52.

Stouffer, S. A., & Spencer, L. M. (1936). Marriage and divorce in recent years. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 188, 56–69.

Wolfers, J. (2006). Did unilateral divorce laws raise divorce rates? A reconciliation and new results. American Economic Review, 96(5), 1802–1820.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge financial support from the Spanish Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (ECO2012-34828, ECO2013-45969-P and ECO2013-41310-R projects), the DGA (ADETRE research group), and FEDER. This paper was partly written while the authors were visiting the Department of Economics, ISEG-Universidade de Lisboa, whose support and hospitality are gratefully acknowledged. The visits were funded by Santander Universidades (Becas Iberoamérica Jóvenes Profesores e Investigadores y Alumnos de Doctorado 2015). Earlier versions of this paper were presented at the 55th Congress of the European Regional Science Association (Lisbon, 2015) and at the 55th Annual Meeting of the Western Regional Science Association (Big Island, 2016), with all the comments made by participants being highly appreciated. Finally, suggestions and observations received from two anonymous referees and the editor (Prof. Shoshana Grossbard) have also significantly improved the version originally submitted. All remaining errors are ours.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

González-Val, R., Marcén, M. Divorce and the business cycle: a cross-country analysis. Rev Econ Household 15, 879–904 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-016-9329-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-016-9329-x