Abstract

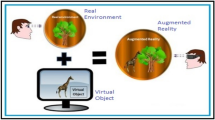

The aim of this paper was to highlight the augmented reality’s potentialities, depicting its main characteristics and focusing attention on what its goal should be in order to have a new technology completely different from those that already exist. From a technological point of view, augmented reality is still in its infancy and so even the general idea of what a good augmented reality should be is still uncertain. Commonly, augmented reality is identified as opposed to the virtual reality because augmented reality merges digital information with the real environment. However, there is another technology, with a different history, which has this same basic goal: ubiquitous computing. The absence of a clear distinction between ubiquitous computing and augmented reality makes it difficult to identify what these two technologies should pursue. I will analyse the main aspects of ubiquitous computing and augmented reality from a phenomenological point of view in order to highlight the main differences and to shed light on the real potentialities of augmented reality, focusing attention on what its goal should be.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

This year is significant because it is the first time the term “augmented reality” was used. However, it is possible even to date back the concept to 1966 when Ivan Sutherland created the first head-mounted display.

AR being a technology that merges reality and virtuality, even the simple connection between the person who is calling (reality) and his name (virtuality) on a mobile phone could be conceived an AR.

Even in his first article, published in 1991, he had already developed prototypes (see Weiser 1991).

“Cyberspace—the world that lies beyond our computer screens in the vast network of computers” (Dodge 1999, p. 1).

For example, in the case of a subject moving on a computer desktop, thanks to the mouse in their hand, we could think the cursor on the screen is the actual body image of the subject, while the whole body schema is related to the mouse and the subject’s hand. On the distinction between body schema and body image (see Gallagher 1995, 2005; Poeck and Orgass 1971).

The term “embodied” is related to the action in the everyday world and the term “virtuality” is related to its computing power.

“Ubiquitous computing will require a new approach to fitting technology to our lives, an approach we call “calm technology” [my emphasis]” (Weiser 1996).

We had an increasing growth of computing power. This is also one of the reasons why “Moore’s law” was coined (see Kuniavsky 2010, chap. 1).

“My colleagues and I at the Xerox Palo Alto Research Center think that the idea of a “personal” computer itself is misplaced and that the vision of laptop machines, dynabooks and “knowledge navigators” is only a transitional step towards achieving the real potential of information technology” (Weiser 1991, p. 1).

As the article “A taxonomy of ubiquitous computing applications” shows (see Jeon et al. 2007).

This case is similar to the case of a black box. It is important to the subject without considering what is actually inside this box. The box has some properties, and we are going to study these properties no matter what makes them.

“The perceived object, the box before me, is more than its momentary appearance” (Kuhn 1968, p. 112).

Dahlstrom identifies these two different positions (see Dahlstrom 2006).

See also (Geniusas (2012), p. 12) in order to hava a wide panorama on the topic

Passive in the Husserlian sense. Passivity in phenomenology is not related to the absence of actions, but to the activities out of the ego’s activity. Therefore, to be passive does not mean to be inert as dead matter, but only to act without the direct action of a subject. See also at page 3.

Using the example we have previously given (see at page 4).

Obviously, the action of the subject is not related to the perception of the technological device in itself, but to the perception of the production of such technology. The subject perceives the text and not the device that produced the text. This is important because it helps to identify this technology as something hidden to the subject even if its production needs attention.

See the Fig. 2 at page 3.

“Ubiquitous computing takes place primarily in the background” (Weiser 1993a, p. 71). Moreover, “We are therefore trying to conceive a new way of thinking about computers, one that takes into account the human world and allows the computers themselves to vanish into the background” (Weiser 1993a, p. 71).

See the outer horizon in Husserl’s phenomenology at page 4.

Weiser clearly explains this point saying that the “old” technology related to the personal computer could not become part of the environment, while he was looking for it. “Silicon-based information technology, in contrast, is far from having become part of the environment” (Weiser 1991, p. 1), “Such machines cannot truly make computing an integral, invisible part of people’s lives” (Weiser 1991, p. 1).

“The most profound technologies are those that disappear” (Weiser 1991).

“Certainly, this collective envisioning of a future saturated technology has been a defining characteristic of ubicomp research” (Dourish and Bell 2011, p. 34).

Where Tech product is the displayed “product” of the technology such as the label.

We still have

$$\begin{aligned} (Subject-Technology)\rightarrow (\{Tech\, product\}-Original\, Object) \end{aligned}$$and not

$$\begin{aligned} (Subject-Technology)\rightarrow Original\, Object. \end{aligned}$$We have this kind of substitution in the case of a radio-telescope where the subject looks at the image in the monitor and not at the original celestial object up in the sky.

See at page 4.

See at page 7.

Embodiment relations are identified by the incorporation of the technology into the perceiving pole of the subject

$$\begin{aligned} (Subject - Technology) \rightarrow Object \end{aligned}$$For example we have this relation in the case of glasses because they withdraw and allow the subject to perceive the external object directly without posing themselves as perceived. On embodiment relations (see Ihde 1990; Verbeek 2005).

See Sect. 3.3.

Another important subject is if there was a human support. On this subject (see Jayanti 2003).

On this feeling and his psychological break down (see Jayanti 2003).

“Yes, Kasparov lost the series, but it was not human versus machine; it was human versus humans-plus-machine, a rather unequal contest to say at least!” (Ihde and Selinger 2004, p. 372).

He trained the computer giving a value to each possible position on the chessboard in order to make the computer move to get a better score.

Deep Blue, the second version of 1997, was created to play chess only and it could evaluate 200 million positions per second (Litch 2002, p. 91).

See at page 8.

Using the curly brackets in order to identify where the attention falls, we have

$$\begin{aligned} (Subject-Technology)\rightarrow \{Digital\, object\} \end{aligned}$$This is the main difference between this schema (\((Subject-Technology)\rightarrow Digital\, object\)) and the previous one related to ubicomp (see at page 7):

$$\begin{aligned} Subject\rightarrow \mathop {(\overbrace{\{Original\, object\}-Tech\, product})}\limits ^{Technology} \end{aligned}$$or

$$\begin{aligned} Subject\rightarrow \mathop {(\overbrace{Original\, object-\{Tech\, product\}}}\limits ^{Technology}). \end{aligned}$$In order to have an example of a technology which will be in the market soon, we can refer to META Glasses (see the website https://www.spaceglasses.com/ or the video on youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b7I7JuQXttw). This technology can provide textual information about the surrounding and the visualisation of digital 3D objects in our world as objects among other objects. Therefore, it provides a “bad” AR and a “bad” AR at the same time.

We can see this particular case in the anime Dennō Coil by Mitsuo Iso. Densuke, a small dog, is created by AR. He barks, runs and he gets ill as common dogs do. Children play with him as if he were a common dog made of flesh.

It is possible to provide an example of an existing technology which produces an “augmented pet”. Georgia tech developed an application for the iPhone which visualises a small dog in front of the subject. See the project “ARf: an Augmented Reality Virtual Pet on the iPhone” (http://ael.gatech.edu/lab/research/art-and-expression/arf-iphone/).

References

Benko H, Jota R, Wilson A (2012) Miragetable: freehand interaction on a projected augmented reality tabletop. In: Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing systems (CHI ’12), ACM, New York, NY, USA, pp 99–208. doi:10.1145/2207676.2207704

Biceaga V (2010) The concept of passivity in Husserl’s phenomenology, contributions to phenomenology, vol 60. Springer, New York

Brainard M (2002) Belief and its neutralization: Husserl’s system of phenomenology in ideas I. Religions of mankind. State University of New York Press, Albany

Carroll L (1869) Alice’s adventures in wonderland. Mac Millan, New York

Cho KK (2007) History and substance of Husserl’s logical investigations, Contributions to Phenomenology, Vol. 55, chap 1, Springer, Netherlands, pp 1–20

Dahlstrom D (2006) Lost horizons: an appreciative critique of enactive externalism. Edizioni ETS, Pisa, pp 211–231

Dodge M (1999) The geographies of cyberspace. http://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/266/1/cyberspace.pdf

Dourish P, Bell G (2011) Divining a digital future. MIT Press, Cambridge

Føllesdal D (1969) Husserl’s notion of noema. J Philos 66:680–687

Gallagher S (1995) Body schema and intentionality. MIT Press, Cambridge, pp 225–244

Gallagher S (2005) Dynamic models of body schematic processes. John Benjamins, Amsterdam, pp 233–250

Geniusas S (2012) Origins of the horizon in Husserl’s phenomenology, contributions to phenomenology, vol 67. Springer London, London

Gibson W (1982) Burning chrome. Omni, New York

Gibson W (1984) Neuromancer. HarperCollins, New York

Hsu FH (2002) Behind Deep Blue: building the computer that defeated the world chess champion. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Husserl E (1939) Erfahrung und Urteil: Untersuchungen zur Genealogie der Logik. Allen and Unwin, London

Husserl E (1950) Ideen zu einer reinen Phänomenologie und phänomenologischen Philosophie. Erstes Buch: Allgemeine Einführung in die reine Phänomenologie, Husserliana, vol III. Martinus Nijhoff, Den Haag

Husserl E (1966) Analysen zur passiven Synthesis aus Vorlesungs- und Forschungsmanuskripten, 1918–1926, Husserliana, vol XI. M. Nijhoff, Den Haag

Ihde D (1990) Technology and the lifeworld. From garden to earth. Indiana University, Bloomington

Ihde D (2004) A phenomenology of technics. Rowman & Littlefield, Lanham, pp 137–160

Ihde D (2009) Postphenomenology and technoscience. The Peking University lectures. State University of New York Press, Albany

Ihde D (2010) Stretching the in-between: embodiment and beyond. Foundations of science. http://www.springerlink.com/content/24r1t57p7w252862

Ihde D, Selinger E (2004) Merleau–Ponty and epistemology engines. Hum Stud 27(4):361–376

Irion R (1997) “Deep blue” inspires deep thinking about artificial intelligence. http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/1997/05/970501194114.htm

Jayanti V (2003) Game over: Kasparov and the machine (film)

Jeon NJ, Leem CS, Kim MH, Shin HG (2007) A taxonomy of ubiquitous computing applications. Wirel Pers Commun 43(4):1229–1239. doi:10.1007/s11277-007-9297-9

Korf RE (1997) Does Deep Blue use AI? In: Collected papers from the 1997 AAAI workshop in Deep Blue versus Kasparov: the significance for artificial intelligence. AAAI Press, pp 1–2. http://www.aaai.org/Papers/Workshops/1997/WS-97-04/WS97-04-001.pdf

Kuhn H (1968) The phenomenological concept of “horizon”. Greenwood Press, Westport, pp 106–123

Kuniavsky M (2010) Smart things: ubiquitous computing user experience design. Morgan Kaufmann, Amsterdam. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/book/9780123748997

Litch M (2002) Philosophy through film. Routledge, London

McDermott D (1997) How intelligent is Deep Blue? http://www.psych.utoronto.ca/users/reingold/courses/ai/cache/mcdermott.html

Milgram P (1994) Augmented reality: a class of displays on the reality–virtuality continuum. SPIE Telemanip Telepresence Technol 2351:282–292

Nagataki S, Hirose S (2007) Phenomenology and the third generation of cognitive science: towards a cognitive phenomenology of the body. Hum Stud 30:219–232. doi:10.1007/s10746-007-9060-y

Newborn M (2011) Beyond Deep Blue: chess in the stratosphere. Springer, New York

Poeck K, Orgass B (1971) The concept of the body schema: a critical review and some experimental results. Cortex 7(3):254–277

Schueler G (1996) How could a computer beat Kasparov fairly? http://www.cis.umassd.edu/~ivalova/Spring08/cis412/Papers/CBTKAS-F.PDF

Selinger E (2006) Normative phenomenology: reflections on Ihde’s significant nudging, chap 6. State University of New York Press, Albany, pp 89–107

Sokolowski R (2000) Introduction to phenomenology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Theodorou P (2006) Perception and action: on the praxial structure of intentional consciousness. Phenomenol Cogn Sci 5(3–4):303–320

Verbeek PP (2005) What things do. Philosophical reflections on technology, agency, and design. Penn State University Press, University Park

Vinge V (2006) Rainbow’s end. Tor Books, New York City

Walton RJ (2002) The horizons of cultural objects. In: Cheung CF, Chvatik I, Copoeru I, Embree L, Iribarne J, W HRS (eds) Essays in celebration of the founding of the organization of phenomenological organizations. http://www.o-p-o.net/essays/WaltonArticle.pdf

Weiser M (1991) The computer for the 21st century. Sci Am 265(3):66–75. http://www.ubiq.com/hypertext/weiser/SciAmDraft3.html

Weiser M (1993a) Hot topics—ubiquitous computing. Computer 26(10):71–72. doi:10.1109/2.237456

Weiser M (1993b) Some computer science issues in ubiquitous computing. Commun ACM 36(7):75–84. doi:10.1145/159544.159617

Weiser M (1996) Open house. Review, the web magazine of the interactive telecommunications program of New York University (film). http://www.ubiq.com/hypertext/weiser/WeiserPapers.html

Weiser M, Brown JS (1996a) The coming age of calm technology

Weiser M, Brown JS (1996b) Designing calm technology. PowerGrid J 1. http://www.ubiq.com/hypertext/weiser/calmtech/calmtech.htm

Zahavi D (2004) Husserl’s noema and the internalism–externalism debate. Inquiry 47(1):42–66

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Liberati, N. Augmented reality and ubiquitous computing: the hidden potentialities of augmented reality. AI & Soc 31, 17–28 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-014-0543-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-014-0543-x