Abstract

Introduction

Minimally invasive calcaneal osteotomy (MICO) is already an established surgical procedure for correcting hindfoot deformities using a lateral approach. So far, no description of a medial approach for MICO has been published.

Material and methods

Between August 2022 and March 2023, 32 consecutive patients (MICO with medial approach, MMICO: n = 15; MICO with lateral approach, LMICO: n = 17) underwent MICO as part of complex reconstructive surgery of the foot and ankle with concomitant procedures. The amount of correction in the axial view of the calcaneus and consolidation rates were evaluated radiographically. Subjective satisfaction, stiffness of the subtalar joint, and pain level (numeric rating scale, NRS) at the level of the heel were assessed clinically. The last follow-up was at 6 months.

Results

All osteotomies consolidated within 6 months after surgery. Displacement of the tuber was 9 mm on average in either group. Relevant subtalar joint stiffness was detected in 5 MMICO and 6 LMICO patients. No relevant differences between the groups were detected for wound healing problems, nerve damage, heel pain or patient satisfaction.

Conclusion

In this study lateral and medial approaches for MICO were performed. Similar degrees of correction and low complication rates were found in both groups. The medial approach for MICO is safe and can be beneficial regarding patient positioning and arrangement of the C‑arm.

Graphic abstract

Zusammenfassung

Einleitung

Die minimal-invasive Kalkaneusosteotomie (MICO) ist bereits ein etabliertes chirurgisches Verfahren zur Korrektur von Rückfußdeformitäten über einen lateralen Zugang. Ein medialer Zugang für die MICO ist bisher nicht beschrieben worden.

Material und Methoden

Zwischen August 2022 und März 2023 wurde bei 32 konsekutiven Patienten (MICO mit medialem Zugang, MMICO: n = 15; MICO mit lateralem Zugang, LMICO: n = 17) im Rahmen einer komplexen rekonstruktiven Fuß- und Sprunggelenkoperation mit begleitenden Eingriffen eine MICO durchgeführt. Das Ausmaß der Korrektur in der axialen Ansicht des Fersenbeins und die Konsolidierungsraten wurden radiologisch ausgewertet. Die subjektive Zufriedenheit, die Steifheit des Subtalargelenks und das Schmerzniveau (numerische Ratingskala, NRS) auf Höhe der Ferse wurden klinisch beurteilt. Die letzte Follow-up-Untersuchung fand nach 6 Monaten statt.

Ergebnisse

Alle Osteotomien konsolidierten innerhalb von 6 Monaten nach dem Eingriff. Die Verschiebung des Tuber calcanei betrug in beiden Gruppen im Durchschnitt 9 mm. Eine relevante Steifigkeit des Subtalargelenks wurde bei 5 MMICO- und bei 6 LMICO-Patienten festgestellt. Hinsichtlich Wundheilungsproblemen, Nervenschäden, Fersenschmerzen oder Patientenzufriedenheit wurden keine relevanten Unterschiede zwischen den Gruppen festgestellt.

Schlussfolgerung

In dieser Studie wurden laterale und mediale Zugänge für die MICO untersucht. In beiden Gruppen wurden ähnliche Korrekturgrade und niedrige Komplikationsraten festgestellt. Der mediale Zugang für die MICO ist sicher und kann hinsichtlich der Patientenpositionierung und der Anordnung des C‑Bogens von Vorteil sein.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Gleich was the first to explain the idea of an osteotomy to change the axis of the calcaneus in 1893 [1]. Since then, several techniques regarding the exact placement of the osteotomy with different fixation devices and varying indications have been described [12, 15]. Nowadays, calcaneal osteotomy can be safely performed through minimally invasive (MI) incisions and are used for varying hindfoot pathologies as displacement of the tuber in all directions can be performed. When comparing minimally invasive calcaneal osteotomy (MICO) to traditional open approaches, the literature shows that MICO causes fewer complications, especially regarding wound healing [10, 23]. Whether an open or MI technique is used, the lateral approach is traditionally preferred for the osteotomy [9, 11, 18, 23, 25]. The patient is usually positioned in a lateral or supine decubitus position to allow access to the lateral heel [5, 18]. Depending on the surgeon’s dominant hand or the image intensifier’s position, this can sometimes be challenging as the foot has to be positioned close to the input window of the C‑arm. Additionally, if the hip is stiff and the leg cannot be rotated in the desired position, it can be a struggle to obtain a clear lateral view of the heel. To avoid these difficulties, we started using a medial incision for the calcaneal osteotomy in patients placed in the supine position during surgery and the leg could easily be externally rotated. In this setting, the calcaneus can be osteotomized under fluoroscopic guidance independent of the surgeon’s dominant hand. Therefore, the present study aimed to evaluate the radiographic results of the MICO via a medial approach and compare it to a control group of patients with an MI osteotomy through a lateral approach. Furthermore, complications should be reported. We hypothesized that neither group had any relevant differences regarding complications and radiographic outcome.

Material and methods

This retrospective study includes 32 consecutive patients (MICO with medial approach, MMICO: n = 15; MICO with lateral approach, LMICO: n = 17) who underwent MICO between September 2022 and March 2023 at 3 institutions (Klinikum rechts der Isar, ATOS Klinik and Schön Klinik MHA). The study was conducted as a proof-of-principle in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the local ethics review board (Technische Universität München, 2022-503-S-KH). Exclusion criteria were lost to follow-up and a patient age < 18 years. Demographic data of included patients are given in Table 1. All MICOs were part of complex reconstructive foot and ankle surgeries with concomitant procedures (Table 2). Preoperatively and 6 months postoperatively, various clinical and radiographic data were collected. Clinically, patients were asked if they would opt for the surgery again (answers: yes/unsure/no). Mobility of the operated and nonoperated subtalar joint was documented and the difference was calculated. This was determined semi-quantitatively: difference < 10°: no significant limitation, > 10°: significant limitation. Additionally, the pain level regarding heel pain (numeric rating scale NRS, 0 no pain–10 worst possible pain) was recorded postoperatively. This modification was applied because multiple other procedures that could interfere with general foot pain were necessary in these patients. Complications (nerve damage, wound healing) were documented. Radiographically, images were taken in a standardized fashion (foot under full weight bearing in dorsoplantar and lateral views, Harris view of the calcaneus), and translation of the tuber was measured. Additionally, a possible loss of correction and the osseous consolidation of the osteotomy were documented. The last follow-up was 6 months on average (5–8 months).

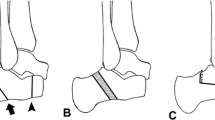

Surgical technique of the MMICO

All operations were performed by two fellowship-trained foot and ankle surgeons with more than 5 years of experience with MI techniques (NH performed all MMICO and 7 LMICO, HH performed 10 LMICO). The MICO was performed first or later during foot reconstruction depending on the concomitant procedures. For the lateral approach, the patient was positioned on the side with the operated foot up or in a supine position with an internally rotated leg. For the MMICO, the patient was supine with the operated leg in 90° external rotation to allow a clear lateral view of the calcaneus. A tourniquet was always applied but not inflated if the MICO was performed first; if the MICO was performed later, the tourniquet was inflated and not routinely opened for the MICO. The osteotomy cuts were V‑shaped if no cranial or caudal translation was desired. Under fluoroscopic guidance, a short incision was centered in the safe zone described by Talusan et al. ([21]; Figs. 1 and 2). A small hemostat and a periosteal elevator were used to remove the soft tissues from the bone. The 2 × 20 mm Shannon burr was inserted, and the osteotomy was performed (Fig. 3). During cutting, the burr was rotated with 6000–8000 revolutions per minute under permanent irrigation with saline. After completion of the osteotomy, the tuber was shifted in the desired direction with the use of an elevator that was introduced through the incision. The tuber was fixed with two K‑wires inserted from posterior. Following a fluoroscopic control via axial and lateral views of the calcaneus, the K‑wires were replaced with one or two cannulated screws (Fig. 4).

Statistical analysis

Normal distribution was verified using D’Agostino-Pearson testing. An independent t‑test and a Mann-Whitney U‑test were performed for normal and non-normal distributed data to describe significant differences between the groups. Statistical significance was assumed for all p-values < 0.05 [23]. All analyses were performed with Python 3.9.6 (https://www.python.org/) and the scipy-library (https://scipy.org/).

Results

Clinical results

Overall, we found comparable satisfaction rates regarding surgical outcomes in both groups. Pain levels (NRS) at the heel were comparable between the groups (MMICO: 10 patients 0, 4 patients 1, 1 patient 2; LMICO: 8 patients 0, 7 patients 1, 2 patients 2). Regarding patient satisfaction 12 of 15 patients after MMICO (80%) and 12 of 17 patients after LMICO (70%) would opt for the surgery again. The rest were unsure but no patient would not opt for the surgery again. Complications are given in Table 3. We found delayed wound healing in one case in both groups. In both cases, the wound healed with conservative measures within 4 weeks of surgery. There was temporary dysesthesia in 4 cases (2 in each group), no relevant nerve damage persisted over 6 weeks. Regarding significant subtalar joint stiffness, we found five patients in the MMICO and six patients in the LMICO group.

Radiographic results

All osteotomies achieved radiological consolidation within 6 months of surgery, and no signs of loosened screws were documented. The displacement of the tuber was, on average 9.3 mm (range 5.7–11 mm) in MMICO, and 9.1 mm (range 6.3–12 mm) in LMICO.

Discussion

The main findings of the present study are that no differences regarding the amount of displacement of the tuber and risk of nerve damage were found, independent of whether a medial or lateral incision for the MICO was chosen. Moreover, complete consolidation of all osteotomies was achieved within 6 months of surgery. The safety of the medial incision, in conjunction with its simplicity regarding placement of the foot and C‑arm offers some advantages in the setting of complex reconstructive procedures in which the MICO usually represents only a small step [3, 17,18,19].

Minimally invasive calcaneal osteotomies offer the same excellent clinical results and mechanical correction with a lower complication rate as open techniques [9, 11]. Therefore, these techniques are gaining more and more acceptance among foot surgeons, and multiple studies confirm these findings (Table 4). Traditionally, calcaneal slide osteotomies are performed through a lateral approach. Here, the medial neurovascular bundle is not at direct risk; therefore, this approach is safe. Nevertheless, the neurovascular bundle can be at risk even if a lateral approach is used and the cut is too distal (Fig. 5). In this context, a safe zone of the skin incision and osteotomy cut have been defined [21]. To our knowledge, no medial incision for a MICO has been described. In our patients treated with MMICO, we could not observe any permanent damage to the neurovascular bundle medially or cutaneous nerves laterally, suggesting this procedure is safe. One might suppose that a medial incision places the medial structures at risk of damage due to its anatomical proximity. We believe the contrary occurs. After medially incising the skin, the soft tissue containing nerves can easily be protected with the nick-and-spread technique. Once the burr is inserted into the bone (safe hole technique), the medial structures cannot be damaged. Another advantage of the medial approach is that if the leg is externally rotated by 90°, the C‑arm can be entered from both sides and positioned independently of either the surgeon’s preferred hand or the patient’s operated foot side.

In our study, 28.1% of osteotomies were lateralizing. It is described that this shift can be somewhat more troublesome because the medial nerves are set under compression. To avoid this complication, some authors recommend protective tarsal tunnel release when performing lateralizing calcaneal osteotomies [2, 13, 24], especially when lateralization of the calcaneal tuberosity of more than 8 mm is performed [6]. Other authors state no beneficial effect with the tarsal tunnel release [20, 22].

One study showed that a lateralizing calcaneal osteotomy performed via an open medial approach had a clinically negligible incidence of neurologic injury while adequate translation was achieved to obtain correction of varus hindfoot deformity. The authors believed there is a less direct and less percussive injury to branches of the tibial nerve when performing the osteotomy from medial to lateral [8]. In our study, we could not find any signs of permanent paresthesia at the level of medial or lateral plantar nerves suggestive of nerve compression in the tarsal tunnel. This can be explained by the fact that we did not perform the MICO on patients with neurological diseases such as hereditary motor sensory neuropathy (HMSN) as, in these patients, the risk of tarsal tunnel syndrome in conjunction with lateral sliding calcaneal osteotomies is thought to be higher [4, 13, 14, 16]. Additionally, we performed a lateral sliding of the tuber not exceeding 15 mm. Furthermore, we agree with other authors that if the medial approach is used the periosteum of the medial calcaneus is routinely elevated or perforated with the Freer before the burr is entered into the bone [8]. This release might also put less stress on the tarsal tunnel if the tuber is slid.

Our study has some limitations. First, it is a retrospective case series with a relatively small sample size, although the number of patients is comparable to other studies dealing with MICO through a lateral approach [9, 11]. Second, the follow-up of 6 months is short. Nevertheless, after 6 months, all osteotomies were consolidated; therefore, the study’s main question regarding the safety of the MMICO could be answered. Third, we did not use a clinically established patient-reported outcome measure (PROM) to evaluate clinical satisfaction after MICO. Therefore, we were not able to objectively compare the results of both groups. On the other hand, this is not possible in our study as MICO was only one part of other procedures (Table 2), and therefore, it cannot be stated which amount of the whole clinical outcome is the result of the MICO. Additionally, although PROMs may be valuable in comparison of various surgical treatments and differences between distinct population groups, clinical interpretation of these differences can sometimes be misleading [7]. Nonetheless, these limitations must be considered before conclusions about daily practical actions are drawn.

Conclusion

This study proves that MICO through a medial incision is as safe and powerful as through a lateral incision. The medial incision does not need the lateral decubitus position, and the C‑arm can be entered from both sides without disturbing the operating field. This allows the surgeon to perform the MICO without changing the patient’s supine position in the setting of complex reconstructive procedures of the foot.

Abbreviations

- MICO:

-

minimally invasive calcaneal osteotomy

- MMICO:

-

medial incision for MICO

- LMICO:

-

lateral incision for MICO

- MI:

-

minimally invasive

References

Gleitch A (1893) Beitrag zur operativen plattfussbehandlung. Arch Klin Chir 46:358–362 (1893)

Bruce BG, Bariteau JT, Evangelista PE et al (2014) The effect of medial and lateral calcaneal osteotomies on the tarsal tunnel. Foot Ankle Int 35(4):383–388

Chadwick C, Whitehouse SL, Saxby TS (2015) Long-term follow-up of flexor digitorum longus transfer and calcaneal osteotomy for stage II posterior tibial tendon dysfunction. Bone Joint J 97-b(3):346–352

Gutteck N, Zeh A, Wohlrab D et al (2019) Comparative results of percutaneous calcaneal osteotomy in correction of Hindfoot deformities. Foot Ankle Int 40(3):276–281

Guyton GP (2016) Minimally invasive osteotomies of the calcaneus. Foot Ankle Clin 21(3):551–566

Halm S, Fairhurst PG, Tschanz S et al (2020) Effect of lateral sliding calcaneus osteotomy on tarsal tunnel pressure. Foot Ankle Orthop 5(3):2473011420931015

Harrasser N, Hinterwimmer F, Baumbach SF et al (2023) The distal metatarsal screw is not always necessary in third-generation MICA: a case-control study. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 143(8):4633–4639 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36577799)

Jaffe D, Vier D, Kane J et al (2017) Rate of neurologic injury following lateralizing calcaneal osteotomy performed through a medial approach. Foot Ankle Int 38(12):1367–1373

Jowett CR, Rodda D, Amin A et al (2016) Minimally invasive calcaneal osteotomy: A cadaveric and clinical evaluation. Foot Ankle Surg 22(4):244–247

Kendal AR, Khalid A, Ball T et al (2015) Complications of minimally invasive calcaneal osteotomy versus open osteotomy. Foot Ankle Int 36(6):685–690

Kheir E, Borse V, Sharpe J et al (2015) Medial displacement calcaneal osteotomy using minimally invasive technique. Foot Ankle Int 36(3):248–252

Koutsogiannis E (1971) Treatment of mobile flat foot by displacement osteotomy of the calcaneus. J Bone Joint Surg Br 53(1):96–100

Krause FG, Pohl MJ, Penner MJ et al (2009) Tibial nerve palsy associated with lateralizing calcaneal osteotomy: case reviews and technical tip. Foot Ankle Int 30(3):258–261

Mittendorf KF, Marinko JT, Hampton CM et al (2017) Peripheral myelin protein 22 alters membrane architecture. Sci Adv 3(7):e1700220

Miyamoto W, Takao M, Uchio Y (2010) Calcaneal osteotomy for the treatment of plantar fasciitis. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 130(2):151–154 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19381659)

Mondelli M, Giannini F, Reale F (1998) Clinical and electrophysiological findings and follow-up in tarsal tunnel syndrome. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 109(5):418–425

Sammarco GJ, Hockenbury RT (2001) Treatment of stage II posterior tibial tendon dysfunction with flexor hallucis longus transfer and medial displacement calcaneal osteotomy. Foot Ankle Int 22(4):305–312

Sherman TI, Guyton GP (2018) Minimal incision/minimally invasive medializing displacement calcaneal osteotomy. Foot Ankle Int 39(1):119–128

Silva MG, Tan SH, Chong HC et al (2015) Results of operative correction of grade IIB tibialis posterior tendon dysfunction. Foot Ankle Int 36(2):165–171

Stødle AH, Molund M, Nilsen F et al (2019) Tibial nerve palsy after lateralizing calcaneal osteotomy. Foot Ankle Spec 12(5):426–431

Talusan PG, Cata E, Tan EW et al (2015) Safe zone for neural structures in medial displacement calcaneal osteotomy: a cadaveric and radiographic investigation. Foot Ankle Int 36(12):1493–1498

VanValkenburg S, Hsu RY, Palmer DS et al (2016) Neurologic deficit associated with lateralizing calcaneal osteotomy for cavovarus foot correction. Foot Ankle Int 37(10):1106–1112

Waizy H, Jowett C, Andric V (2018) Minimally invasive versus open calcaneal osteotomies—Comparing the intraoperative parameters. Foot (Edinb) 37:113–118

Walls RJ, Chan JY, Ellis SJ (2015) A case of acute tarsal tunnel syndrome following lateralizing calcaneal osteotomy. Foot Ankle Surg 21(1):e1–e5

Walther M, Kriegelstein S, Altenberger S et al (2016) Percutaneous calcaneal sliding osteotomy. Oper Orthop Traumatol 28(4):309–320

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. SB and NH performed data collection. RSS performed statistical analyses. NH, HH, and SB wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

S. Beischl, N. Harrasser, A. Toepfer, C. Scheele, R. Smits Sererna, M. Walther, F. Lenze and H. Hörterer declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical standards

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants or on human tissue were granted by the Ethics Committee of the TU Munich (Registration Number 2022-503-S-KH) and with the 1975 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Scan QR code & read article online

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Beischl, S., Harrasser, N., Toepfer, A. et al. Feasibility and safety of minimally invasive calcaneal osteotomy (MICO) through a medial approach: a case-control study. Orthopädie 53, 39–46 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00132-023-04460-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00132-023-04460-9