Abstract

Purpose

There are elevated mental health concerns in paramedic students, but estimates vary between studies and countries, and no review has established the overall prevalence. This systematic review addressed this by estimating the global prevalence of common mental health disorders, namely anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), in paramedic students internationally.

Methods

A systematic search of six databases, including MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, Scopus, and medRxiv, was conducted to identify studies relating to mental health among paramedicine students. The search encompassed studies from inception until February 2023. To be considered for inclusion in the review, the studies had to report prevalence data on at least one symptom of anxiety, depression, or PTSD in paramedicine students, using quantitative validated scales. The quality of the studies was assessed using Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Checklist, which is a specific methodological tool for assessing prevalence studies. Subgroup analyses were not conducted due to insufficient data.

Results

1638 articles were identified from the searches, and 193 full texts were screened, resulting in 13 papers for the systematic review and meta-analysis. The total number of participants was 1064 from 10 countries. The pooled prevalence of moderate PTSD was 17.9% (95% CI 14.8–21.6%), anxiety was 56.4% (95% CI 35,9–75%), and depression was at 34.7% (95% CI 23.4–48.1%).

Conclusion

This systematic review and meta-analysis has found that paramedicine students globally exhibit a high prevalence of moderate PTSD, anxiety, and depression. The prevalence of these mental health conditions surpasses those among paramedic providers and the general population, as indicated by previous reviews. Further research is therefore warranted to determine appropriate support and interventions for this group.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Mental health disorders are common in the general population, with anxiety affecting around 301 million (4% of the global population) according to the Global Burden of Disease Study in 2019 [18]. Similarly, depression affecting around 280 million [52]. The underlying causes of mental health disorders are complex, but evidence suggests that risk of these is elevated in occupational groups who experience potentially stressful events in the course of their work [57, 59, 57]. One such high-risk group is paramedics [20]. Several studies have found a higher rate of mental health issues (e.g., depression, PTSD, stress) among paramedics than in the general population [4, 5, 29, 36, 47]. For example, in Saudi Arabia, the prevalence of anxiety and depression among the general population is between 12.4% and 12.7% respectively [1, 2]. However, for paramedics and paramedic students, the rates of anxiety are 19.3% [3] and 24.3% [6].

Paramedics are a fundamental part of the healthcare system, enacting clinical and non-clinical roles in a variety of unscheduled and dynamic settings (e.g., prehospital; [13, 54]). Thus, they face innumerable challenges as they must handle different cases in unpredictable contexts [10, 26] and be ready to make life-or-death decisions in a limited time frame. Some of the greatest burdens to paramedics’ mental health are found in their daily tasks and work environments, including attending to traumatic cases (e.g., death, severe trauma), lack of resources, and long shifts [4, 5], 58, 20] [33]. These burdens pose significant challenges, including related physical and mental demands, and so it is unsurprising that the risk of common mental health disorders is elevated in this group [4, 5, 24, 40].

Internationally, the training for paramedics involves practical clinical placements [14]. As such, paramedic students also face similar challenges to qualified paramedics [16]. Furthermore, paramedic students encounter additional challenges related to academic requirements and training placements [7, 16, 26]. A limited number of studies have examined the mental wellbeing of paramedic students and their findings have suggested that mental health disorders are more prevalent among paramedic students than the general population [6, 16, 36]. However, the global prevalence of mental health problems among paramedic students is unclear. Compared to pharmacy, medicine, and nursing students [27, 46, 48], respectively), paramedicine is an understudied major health speciality in tertiary education, with no current systematic review investigating the prevalence of mental health issues among the paramedic student population [19]. Quantifying the global rate of mental health disorders among paramedic students could highlight the extent to which addressing this should be prioritised by policymakers, researchers, clinicians, and tertiary academicians to understand the mental health needs of paramedic students [19].

Accordingly, this systematic review aimed to estimate the prevalence of common mental health disorders (i.e., anxiety, depression, PTSD) among paramedic students internationally [30, 53].

Methods

The current systematic review followed the PRISMA statement and the Institute of Medicine’s Standards for Systematic Reviews [42, 34]. A protocol was registered in the PROSPERO International Register of Systematic Reviews (Registration No: CRD42022303570). To identify relevant studies of mental health issues among paramedic students and associated variables, major health databases were searched from inception to January 30, 2022, with the search updated on February 12, 2023.

Search strategy

To identify relevant citations for inclusion, six databases were searched: CINAHL (EBSCOhost), EMBASE (ELSEVIER), Medline (Ovid), PsycINFO, Scopus, medRxiv (grey literature and pre-prints from bioRxiv and medRxiv). To identify relevant studies with data on mental health disorders among paramedic students and associated variables, the databases were searched from inception to January 30, 2022, with the search updated on February 12, 2023. The search strategy included Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms and keywords/phrases describing the population and the outcome; a language restriction was also placed on potentially relevant records. Further, the researchers manually searched reference lists and citation chaining of the included articles, which helped identify additional relevant articles. The search results from each database were exported, and the duplicates were removed. Only articles in the English language were included. All searches employed two main search blocks: mental health (anxiety, depression, and PTSD) and paramedic students.

Eligibility criteria

The criteria for studies to be eligible for inclusion regarding population were if they only included participants enrolled in a paramedicine academic training programme and if they excluded qualified paramedics and volunteers. No interventions or comparators were applied in the review, and all quantitative study designs were included. Where studies reported more than one measurement of the outcome variables of interest (i.e., in the case of cohort/intervention studies), we included baseline measurements in our analysis. Additionally, mixed-method studies with quantitative data were also considered. The inclusion criteria included studies that measured anxiety, depression, or PTSD symptoms using any type of quantitative design, including grey literature. The exclusion criteria included qualitative studies without any quantitative element and studies that did not use validated questionnaires to measure outcome variables. The review’s primary outcomes were the prevalence of anxiety, depression, and PTSD among paramedic students, and there were no secondary outcomes.

Study selection

The search results from each database were exported to Endnote X8.2 (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, United States), and all duplicates were removed. The study selections were completed in two stages: in the first stage, the titles and abstracts of the identified studies were screened; in the second stage, the full texts of the retained studies were accessed and further screened according to the eligibility criteria. A percentage of titles/abstracts (10%) was screened independently by two reviewers to check for agreement (KA and RA). To estimate the level of agreement, we calculated the Kappa score, which indicated good agreement (k = 0.739). The remaining screening of titles/abstracts against the selection criteria was undertaken by two reviewers (AA and RA). Three independent reviewers each undertook the full-text screening (AA, KA, and RA). All disagreements were resolved through discussion; there was 100% agreement between reviewers on the second review.

Data extraction

A data extraction form was devised in Excel 2016 16.7 (Microsoft Inc.) and piloted with five randomly selected studies. The quantitative data for the meta-analysis were extracted in a separate Excel file. The following descriptive information was extracted from the eligible studies: (1) study (country, recruitment methods, research design), (2) participants (age, gender, sample size, setting), (3) outcome variables (assessments to measure anxiety, depression, and/or PTSD and the reported prevalence of each outcome). The data were extracted by AA and reviewed by CK, JJ, KA, and RA.

Quality assessment

The quality of the studies was assessed independently by two reviewers using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal Checklist for Studies Reporting Prevalence Data [60]. Through this instrument, study quality was assessed across nine domains: the suitability of the sample to represent the target population, the recruitment methods, the sample size, the identification of the sample and the subjects, the data analysis approach used for the sample, the methods chosen to identify the outcome, the measurement of the condition, the appropriateness of the statistical findings, and the adequacy of the response rate. The nine items can be answered with ‘Yes’, ‘No’, ‘Unclear’, or ‘Not Applicable’. All disagreements between authors were resolved through discussion.

Data analysis

All studies included in this project are described in a narrative review, including a table that quantifies our primary outcomes, design, and participant characteristics (see Table 1). The methods of the included studies varied, with different scales and cut-off scores implemented to identify the prevalence of anxiety, depression, and PTSD. To ensure an accurate interpretation, the prevalence of the selected mental health disorders was estimated using the moderate and above cut-off levels recommended on each of the scales.

PTSD, anxiety and depression studies included in the meta-analysis were examined using comprehensive meta-analysis (CMA) software. A random-effects meta-analysis was conducted using pooled mean prevalence estimates and expressed as an event rate. The results were calculated using a 95% confidence interval (CI) and p-value. A high heterogeneity was expected, given the probable levels of heterogeneity. The random effect is preferred in such cases; however, the fixed model is favoured for prevalence studies to maintain the weight of studies. Therefore, both the random and fixed effects were displayed in the results (M. [12, 35]). Where appropriate, heterogeneity factors were assessed using the Higgins inconsistency test (I2) and p-value. A p-value below 0.05 was considered statistically significant [25]. The risk of publication bias was examined through Egger’s test and Begg’s funnel plot, which were prepared using CMA software [9, 15]. See Appendix 1, 2, and 3C. No subgroup analyses were performed due to insufficient data available for analysis.

Results

Study characteristics

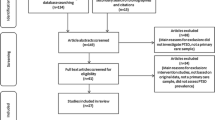

A total of 1638 articles from six databases were identified (See Fig. 1). After removing duplicates, 1,081 studies remained. During the title and abstract screening phase, 850 studies were excluded as they did not match the current systematic review criteria; 193 studies were screened fully. Only 38 studies met the inclusion criteria, and a further 23 of these were excluded as the researchers could not obtain the relevant data, even after contacting the study authors. Thus, 13 studies were included in the systematic review [6, 8, 13, 16, 21, 22, 32, 34, 37,38,39, 51, 55, 56], and met the criteria for meta-analysis. Of these 13 studies, six were included in the final set for PTSD, seven for anxiety, and six for depression. Please refer to Fig. 1 for the PRISMA diagram.

“PRISMA 2020 Flow Diagram” [42]

Articles were primarily excluded in the first and second screening stages due to the study population (n = 626), outcomes (n = 234), design (n = 137), and publication type (n = 10). During the eligibility stage, articles were primarily excluded because the rate of each disorder of interest among paramedic students could not be identified, a lack of detailed results provided for each scale, and reporting of the mean results only.

A total of 1623 participants were included in the review; from this sample, 1064 paramedic students from 13 studies conducted across 10 countries were included in the meta-analyses. The included studies were published between 1996 and 2022, with the number of studies increasing with time.

Six studies were cross-sectional, including a prevalence-based study; two were mixed methods; two were longitudinal, including a study that provided outcomes from two different collection points as well as baseline prevalence data for the second dataset; three were cohort studies; and two used alternative study designs. Regarding the sampling techniques, 12 studies used non-random methods (purposeful sampling and convenience sampling), while the remaining three used random or census methods. If the sample methods were not mentioned, they were listed as non-random methods.

Regarding gender, 56% of the participants were male and 43% were female. In two studies, no gender information was listed. All the studies used self-report scales to identify the prevalence of mental health conditions, and no study used a clinical diagnostic interview. For further information, see Appendix 2, 3, 4B.

Mental health outcomes

Prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder

Six studies reported symptoms of PTSD among paramedic students. These symptoms were assessed using the following four scales: the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5), the Posttraumatic Stress Diagnostic Scale (PDS), the Davidson Trauma Scale (DTS), and Keane’s MMPI scale (PK) for PTSD. The pooled prevalence estimate of moderate PTSD was 17.9% (95% CI, 14.8–21.6%; see Appendix Table E), with a range of 5–22%. The heterogeneity was low (I2 = 1%, p < 0.001), reflecting variance in true effects rather than sampling error. This was evidenced through the Q-value, which was 6.055 with six degrees of freedom and p 0.417. The pooled estimate of mild PTSD was not presented due to a lack of available data for four studies.

Prevalence of anxiety

Seven studies reported symptoms of anxiety among paramedic students. Five scales were used in these studies, including the seven-item Generalised Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7), Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21), Westside Test Anxiety Scale (WTA), Trait Anxiety Inventory (TAI), and State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI). The pooled estimated prevalence of moderate anxiety was found to be 56.4% (95% CI 35.9%, 75%). While the prevalence of mild anxiety, according to the analysis of four studies, was estimated at 27.1% (95% CI 15.8%, 42.4%). The estimated range of moderate anxiety on each study varied between 24.3 and 94%. The statistical analysis revealed high heterogeneity (I2 = 96%, p < 0.001) among the studies, indicating a difference in true effects rather than sampling error. The Q-value was 155.907 with seven degrees of freedom and p < 0.001. Subgroup analyses were not conducted due to insufficient studies for comparison.

Prevalence of depression

Six studies reported symptoms of depression among paramedic students. These studies used six scales: the Beck Depression Inventory and Revised Beck Depression Inventory (BDI & BDI-II), the DASS-21, the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), the nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), and the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10). Based on six scales, the prevalence of moderate depression was estimated at 34.7% (95% CI 0.234–0.481). The range of prevalence estimates across the studies was between 8 and 56.2%. However, there was a high level of heterogeneity between the studies, with an I2 of 83%, indicating a difference in true effects rather than sampling error. The Q-value is 28.616 with 5 degrees of freedom and p < 0.001. Unfortunately, the pooled estimate of mild depression could not be presented due to the lack of available data. Further, subgroup analyses were not conducted as there was insufficient data to make comparisons.

Publication bias

Various methods were used to evaluate publication bias. For PTSD, Begg’s funnel plot indicated symmetry (see graph 1c), while Egger’s test showed non-significance with an intercept (B0) of – 1.685 and a 95% confidence interval ( – 3.99623, 0.62586) and a p-value of 0.0598. The null hypothesis was not rejected with a criterion alpha of 0.100, as the actual effect size varied among the studies. The prediction interval was estimated to be between 13.8 and 23%, with the true effect size falling within this range for 95% of similar populations. For anxiety, Begg’s funnel plot suggested publication bias (see graph 2c). Still, Egger’s test did not provide any significant evidence, with an intercept (B0) of 5.71895, a 95% confidence interval ( – 3.22881, 14.66671), and a p-value of 0.08443. The null hypothesis was rejected with a criterion alpha of 0.100, as the true effect size differed in all studies. The prediction interval was estimated to be between 6.3 and 96.1%, with the true effect size in 95% of all comparable populations falling in this range. For depression, while there was possible publication bias due to a slightly asymmetric Begg’s funnel plot, Egger’s test (p = 0.18) found no significant evidence of bias, with an intercept (B0) of – 2.19777, a 95% confidence interval (-8.28963, 3.89409), and a p-value of 0.18659. The null hypothesis was rejected with a criterion alpha of 0.100, as the true effect size differed in all studies. The prediction interval was estimated to be between 8.2 and 75.9%, with the true effect size in 95% of all comparable populations falling within this range.

Sensitivity analyses

In order to test sensitivity, the leave-one-out method was used, as described by Higgins et al. [61]. The prevalence of PTSD remained unchanged as a result of the application, with minor changes ranging from 0.06% to 13.5% in six studies and remaining significant. This suggests that a single study did not influence the findings, as two studies showed an increase of 2.3% and a decrease of 5.3%, respectively. For anxiety, the prevalence changed in three studies, while it increased from 5.4% to 10% in four studies. The remaining three studies showed an increase of 3.9–5.6%, although the relative weight remained almost the same in five studies. Regarding depression, the prevalence remained unchanged as a result of the application, with slight changes ranging from 0.07% to 3% in four studies. However, in only two studies, the difference was between 3 and 7%, indicating that two to four studies influenced the results for anxiety and depression.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review and meta-analysis examining the prevalence of anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder among the paramedic student population. Accordingly, the current project presents a major contribution to the literature as it illustrates the prevalence of mental health conditions using 15 studies from 10 countries examining a total of 1,392 paramedic students. The prevalence demonstrated high rates of moderate-to-high anxiety (56%), depression (34%), and PTSD (17.9%). These findings are consistent with a systematic review of paramedics, which reported lower rates of PTSD than other mental health conditions [43].

The pooled estimate for mental health disorders among paramedicine students was higher than those found in similar reviews of qualified paramedics [17, 28, 41, 43]. It is possible that this is due to stressors related to the experiences involved in paramedicine training programmes. The clinical training for paramedicine varies by country and university,some students are sent to prehospital providers and different hospital departments, while others receive further training facilities. This diversity of experiences adds to the complexity of their training and the challenges they face. Furthermore, some programs send students for clinical training as early as their first month of the program. The training focuses on monitoring the field and caring for patients in time-sensitive situations, in a limited space, and with several cases and challenges encountered. It is also worth noting that the current prevalence of mental health conditions among paramedic students is higher than in other student populations, indicating the need for collective attention and action to prevent adverse effects on paramedicine student wellbeing [7, 23, 44] and educational outcomes [31].

The results of our systematic review have shown that paramedic students are more likely to experience anxiety than other mental health conditions. This is consistent with wider trends in mental health disorder occurrence, which highlight anxiety as the most common mental health disorder [18]. This could also be attributed to the COVID-19 pandemic, which was initially associated with an increase in anxiety worldwide [56]. However, more recent meta-analyses comparing mental health symptoms before and after the COVID-19 pandemic suggests any initial differences in mental health symptoms in the general population have since reduced to pre-pandemic levels, with only a slight maintained increase in healthcare providers [45, 49, 50].

The findings revealed substantial heterogeneity among all the mental health outcomes. It was particularly important to consider the high heterogeneity between anxiety, depression, and PTSD when interpreting the estimated pooled prevalence in our meta-analysis of the percentage of variability (I2). Each disorder had between six and six to seven studies with eight intakes, such as PTSD. Generally, estimates of heterogeneity based on fewer than 10 studies are unreliable [11]. As a result of the limited data available, a subgroup analysis could not be performed to test for evidence related to content or screening tools. Furthermore, we could not fully explain the high heterogeneity, particularly given the limited number of studies and the different scales used.

Regarding PTSD, studies that used the PCL-5 showed a similar prevalence rate (i.e., between 16 and 17%). However, the sample size and the date of the study showed no significance. Regarding depression, no scales showed any similar patterns to anxiety and PTSD. The studies published since the COVID-19 pandemic reported higher rates of depression than those published before, but it should be noted that all included studies were conducted during earlier phases of the pandemic and wider trends suggest that rates of depression have since returned to pre-pandemic levels [45, 49, 50].

Strengths and limitations

The primary strength of this systematic review is that it focuses on an international population with no limits to specific geographic areas or academic systems. Further, the study was registered on Prospero and followed the PRISMA guidelines to ensure methodological rigour. Two reviewers screened all the studies in the title and abstract stages, with a third reviewer conducting a full review for the data extraction.

However, there are several limitations to the employed methodology. The majority of the studies in the review used non-random sampling methods, which could generate selection bias. Some studies may have been missed as only articles written in English were included in the systematic review. Additionally, while preprint study was included to gather as much data as possible, the results of such studies could change from preprint to publication but that was not the case in the studies included.

The findings revealed substantial heterogeneity among all the mental health outcomes. It was particularly important to consider the high heterogeneity between anxiety, depression, and PTSD when interpreting the estimated pooled prevalence in our meta-analysis of the percentage of variability (I2). Each disorder had between six to seven studies with eight intakes, such as anxiety. Generally, estimates of heterogeneity based on fewer than 10 studies are unreliable [11]. As a result of the limited number of studies available to be included in the review, it was not possible to conduct subgroup analyses or meta-regression to investigate moderating effects or to compare for differences according to factors such as screening tools used [64, 65]. Furthermore, we could not fully explain the high heterogeneity, particularly given the limited number of studies and the different scales used. This issue was particularly evident in studies from countries with unconventional paramedicine training systems, such as India and Iran. Further, although the researchers attempted to contact study authors who did not list their full outcomes, many did not respond, despite being contacted over three times in a six-month period.

Further, the samples used in the studies were limited, with some being from one setting and one university only. Thus, the approach lacked randomisation. Begg’s funnel plots revealed signs of slight-to-high publication bias, but Egger’s test results did not reflect the same bias. The limited sample and lack of available data undoubtedly contributed to these discrepancies.

Conclusion

The present systematic review and meta-analyses provide the most comprehensive information on the prevalence of anxiety, depression, and PTSD among international paramedic students to date. Results suggest that paramedic students are at risk for common mental health conditions, particularly anxiety. This review can guide future research on the mental health of paramedic students internationally, a population that faces numerous and varied challenges and stressors with long-term negative effects. All parties involved, from academic administrators to service providers, need to take decisive action to meet the needs and address the concerns of paramedic students before they enter the field. Globally, universities must implement more support initiatives and improve existing mental health interventions in paramedicine programmes, particularly in collaboration with paramedic students.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are publicly available in published studies.

References

Ahn E, Kang H (2018) Introduction to systematic review and meta-analysis. Korean J Anesthesiol 71(2):103–112. https://doi.org/10.4097/kjae.2018.71.2.103

Alhabeeb AA, Al-Duraihem RA, Alasmary S, Alkhamaali Z, Althumiri NA, BinDhim NF (2023) National screening for anxiety and depression in Saudi Arabia 2022. Front Public Health 11:1213851. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1213851

Almutairi I, Al-Rashdi M, Almutairi A (2020) Prevalence and predictors of depression, anxiety and stress symptoms in paramedics at Saudi Red Crescent Authority. Saudi J Med Med Sci 8(2):105. https://doi.org/10.4103/sjmms.sjmms_227_18

Alshahrani K, Johnson J, O’Connor DB (2022) Coping strategies and social support are associated with post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms in Saudi paramedics. Int J Emerg Serv 11(2):361–373. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJES-08-2021-0056

Alshahrani KM, Johnson J, Hill L, Alghunaim TA, Sattar R, O’Connor DB (2022) A qualitative, cross-cultural investigation into the impact of potentially traumatic work events on Saudi and UK ambulance personnel and how they cope. BMC Emerg Med 22(1):116. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12873-022-00666-w

Alzahrani A, Alzahrani A (2021) Abdulrahman Bayazeed Department of Family Medicine, King Abdulaziz Medical City Ministry of the National Guard-Health Affairs. Medicine https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-956849/v1

Alzahrani A, Keyworth C, Wilson C, Johnson J (2023) Causes of stress and poor wellbeing among paramedic students in Saudi Arabia and the United Kingdom: a cross-cultural qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res 23(1):444. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-023-09374-y

Bazrafshan M-R, Jokar M, Rahmati M, Ahmadi S, Kavi E, Sookhak F, Aliabadi SH (2019) The Relationship between Depression and Internet Addiction among Paramedical Students in Larestan, Iran. J Clin Diagnost Res. https://doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/2019/36363.12742

Begg CB, Mazumdar M (1994) Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics 50(4):1088. https://doi.org/10.2307/2533446

Birtill M, King J, Jones D, Thyer L, Pap R, Simpson P (2021) The use of immersive simulation in paramedicine education: a scoping review. Interact Learn Environ https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2021.1889607

Biondi-Zoccai G, Lotrionte M, Landoni G, Modena MG (2011) The rough guide to systematic reviews andmeta-analyses. HSR Proceedings in Intensive Care & Cardiovascular Anesthesia 3(3):161–173

Bonde JPE (2008) Psychosocial factors at work and risk of depression: a systematic review of the epidemiological evidence. Occupational and Environmental Medicine 65(7):438. https://doi.org/10.1136/oem.2007.038430

Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR (2021) Introduction to Meta-Analysis ((Second ed.)). Wiley

Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR (2010) A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Res Synthesis Methods 1(2):97–111. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.12

Byrne A, Barber R, Lim CH (2021) Impact of the <scp>COVID</scp> -19 pandemic – a mental health service perspective. Prog Neurol Psychiatry 25(2):27. https://doi.org/10.1002/pnp.708

Debray TPA, Moons KGM, Riley RD (2018) Detecting small-study effects and funnel plot asymmetry in meta-analysis of survival data: a comparison of new and existing tests. Res Synth Methods 9(1):41–50. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1266

Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, Minder C (1997) Papers Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629

Fjeldheim CB, Nöthling J, Pretorius K, Basson M, Ganasen K, Heneke R, Cloete KJ, Seedat S (2014) Trauma exposure, posttraumatic stress disorder and the effect of explanatory variables in paramedic trainees. BMC Emerg Med 14(1):11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-227X-14-11

Frajerman A, Chaumette B, Krebs M-O, Morvan Y (2022) Mental health in medical, dental and pharmacy students: a cross-sectional study. J Affect Disord Rep 10:100404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadr.2022.100404

Fullerton CS, Ursano RJ, Wang L (2004) Acute stress disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, and depression in disaster or rescue workers. Am J Psych 161(8):1370–1376. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.161.8.1370

GBD Results Tool. In: Global Health Data Exchange [website]. Seattle: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (2019) (https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results?params=gbd-api-2019-permalink/716f37e05d94046d6a06c1194a8eb0c9, accessed 29 April 2024).

Geissbühler M, Hincapié CA, Aghlmandi S et al (2021) Most published meta-regression analyses based on aggregate data suffer from methodological pitfalls: a meta-epidemiological study. BMC Med Res Methodol 21:123. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-021-01310-0

Gilroy R (2018). Mental health: caring for the paramedic workforce. J Paramed Pract 10(5):192–193. https://doi.org/10.12968/jpar.2018.10.5.192

Grevin F (1996) Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, Ego Defense Mechanisms, and Empathy among Urban Paramedics. Psychol Rep https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1996.79.2.483

Guadagni V, Cook E, Hart C, Burles F, Iaria G (2018) Poor sleep quality affects empathic responses in experienced paramedics. Sleep Biol Rhythms 16(3):365–368. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41105-018-0156-8

Hansen CD, Rasmussen K, Kyed M, Nielsen KJ, Andersen JH (2012) Physical and psychosocial work environment factors and their association with health outcomes in Danish ambulance personnel – a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 12(1):534. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-534

Harvey SB, Modini M, Joyce S, Milligan-Saville JS, Tan L, Mykletun A, Bryant RA, Christensen H, Mitchell PB (2017) Can work make you mentally ill? a systematic meta-review of work-related risk factors for common mental health problems. Occupat Environ Med 74(4):301–310. https://doi.org/10.1136/oemed-2016-104015

Hegg-Deloye S, Brassard P, Jauvin N, Prairie J, Larouche D, Poirier P, Tremblay A, Corbeil P (2014) Current state of knowledge of post-traumatic stress, sleeping problems, obesity and cardiovascular disease in paramedics. Emerg Med J 31(3):242–247. https://doi.org/10.1136/emermed-2012-201672

Higgins JPT (2003) Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 327(7414):557–560. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557

Higgins JP (2008) Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions (version 5.0. 1)

Holmes L, Jones R, Brightwell R, Cohen L (2017) Student paramedic anticipation, confidence and fears: Do undergraduate courses prepare student paramedics for the mental health challenges of the profession? Australasian J Paramed https://doi.org/10.33151/ajp.14.4.545

Huang YQG (2022) Prevalence of Anxiety and Depression Among Pharmacy Students: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Ibrahim AK, Kelly SJ, Adams CE, Glazebrook C (2013) A systematic review of studies of depression prevalence in university students. J Psychiatr Res 47(3):391–400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.11.015

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Standards for Systematic Reviews of Comparative Effectiveness Research. In: Eden J, Levit L, Berg A, Morton S(Eds.). (2011). Finding What Works in Health Care: Standards for Systematic Reviews. National Academies Press (US)

Khan WAA, Conduit R, Kennedy GA, Jackson ML (2020) The relationship between shift-work, sleep, and mental health among paramedics in Australia. Sleep Health 6(3):330–337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleh.2019.12.002

Kirby R, Shakespeare-Finch J, Palk G (2011) Adaptive and maladaptive coping strategies predict posttrauma outcomes in ambulance personnel. Traumatol 17(4):25–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534765610395623

Kola L, Kohrt BA, Hanlon C, Naslund JA, Sikander S, Balaji M, Patel V (2021) Correction to Lancet Psychiatry 2021; Published online Feb 24. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00025-0. The Lancet Psychiatry 8(5):e13. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00090-0

Kondirolli F, Sunder N (2022) Mental health effects of education. Health Econ 31(S2):22–39. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.4565

Krifa I, van Zyl LE, Braham A, Ben Nasr S, Shankland R (2022) Mental health during COVID-19 Pandemic: the role of optimism and emotional regulation. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(3):1413. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031413

Lawn S, Roberts L, Willis E, Couzner L, Mohammadi L, Goble E (2020) The effects of emergency medical service work on the psychological, physical, and social well-being of ambulance personnel: a systematic review of qualitative research. BMC Psychiatry 20(1):348. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02752-4

Lowery K, Stokes MA (2005) Role of peer support and emotional expression on posttraumatic stress disorder in student paramedics. J Traum Stress. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20016

Lucchetta RC, Lemos IH, Gini ALR, de Cavicchioli SA, Forgerini M, Varallo FR, de Nadai MN, Fernandez-Llimos F, Mastroianni PC (2022) Deficiency and insufficiency of vitamin d in women of childbearing age: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Revista Brasileira de Ginecologia e Obstetrícia/RBGO Gynecology and Obstetrics 44(04):409–424. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0042-1742409

Mackinnon K, Everett T, Holmes L, Smith E, Mills B (2020) Risk of psychological distress, pervasiveness of stigma and utilisation of support services: Exploring paramedic perceptions. Australasian J Paramed https://doi.org/10.33151/ajp.17.764

McKinnon A, Lorenz H, Salkovskis P, Wild J (2021) Abstract thinking as a risk factor for the development of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in student paramedics. J Trauma Stress. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22749

Mehta D, Bruenig D, Pierce J, Sathyanarayanan A, Stringfellow R, Miller O, Mullens AB, Shakespeare-Finch J (2022) Recalibrating the epigenetic clock after exposure to trauma: The role of risk and protective psychosocial factors. J Psychiatr Res 149:374–381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.11.026

Miller O, Shakespeare-Finch J, Bruenig D, Mehta D (2020) DNA methylation of NR3C1 and FKBP5 is associated with posttraumatic stress disorder, posttraumatic growth, and resilience. Psychol Trauma Theory Res Pract Policy 12(7):750–755. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000574

Munn Z, Moola S, Lisy K, Riitano D, Tufanaru C (2015) Methodological guidance for systematic reviews of observational epidemiological studies reporting prevalence and cumulative incidence data. Int J Evidence-Based Healthcare 13(3):147–153. https://doi.org/10.1097/XEB.0000000000000054

O’Hara R, Johnson M, Siriwardena AN, Weyman A, Turner J, Shaw D, Mortimer P, Newman C, Hirst E, Storey M, Mason S, Quinn T, Shewan J (2015) A qualitative study of systemic influences on paramedic decision making: care transitions and patient safety. J Health Services Res Policy 20(1_suppl): 45–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/1355819614558472

Pacheco JP, Giacomin HT, Tam WW, Ribeiro TB, Arab C, Bezerra IM, Pinasco GC (2017) Mental health problems among medical students in Brazil: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Bras Psiquiatr 39(4):369–378. https://doi.org/10.1590/1516-4446-2017-2223

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, Moher D (2021) The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Petrie K, Milligan-Saville J, Gayed A, Deady M, Phelps A, Dell L, Forbes D, Bryant RA, Calvo RA, Glozier N, Harvey SB (2018) Prevalence of PTSD and common mental disorders amongst ambulance personnel: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 53(9):897–909. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-018-1539-5

Proctor EK, Landsverk J, Aarons G, Chambers D, Glisson C, Mittman B (2009) Implementation Research in Mental Health Services: an Emerging Science with Conceptual, Methodological, and Training challenges. Administration and Policy Mental Health Mental Health Servic Res 36(1):24–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-008-0197-4

Robinson E, Sutin AR, Daly M, Jones A (2022) A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies comparing mental health before versus during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. J Affect Disord 296:567–576. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.09.098

Rotenstein LS, Ramos MA, Torre M, Segal JB, Peluso MJ, Guille C, Sen S, Mata DA (2016) Prevalence of depression, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation among medical students. JAMA 316(21):2214. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.17324

Rybojad B, Aftyka A, Baran M, Rzońca P (2016) Risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in polish paramedics: a pilot study. J Emerg Med 50(2):270–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2015.06.030

Sarokhani D, Delpisheh A, Veisani Y, Sarokhani MT, Manesh RE, Sayehmiri K (2013) Prevalence of depression among University Students: a systematic review and meta-analysis study. Depress Res Treat 2013:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/373857

Stansfeld SA, Shipley MJ, Head J, Fuhrer R, Kivimaki M (2013) Work Characteristics and personal social support as determinants of subjective well-being. PLoS ONE 8(11):e81115. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0081115

Steeg S, John A, Gunnell DJ, Kapur N, Dekel D, Schmidt L, Webb RT (2022) The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on presentations to health services following self-harm: systematic review. British J Psychiatry 221(4):603–612

Sun Y, Wu Y, Fan S, Dal Santo T, Li L, Jiang X, Thombs BD (2023) Comparison of mental health symptoms before and during the covid-19 pandemic: evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis of 134 cohorts. BMJ. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2022-074224

Uzuntarla Y (2018) Learning Approach and Trait Anxiety on Paramedic and Nursing Students. Australasian J Paramed 15:1–6. https://doi.org/10.33151/ajp.15.4.569

World Health Organization (2023) Depression. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression (Accessed April 28, 2024)

World Health Organization (2020) World Mental Health Day: an opportunity to kick-start a massive scale-up in investment in mental health. https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/27-08-2020-world mental-health-day-an-opportunity-to-kick-start-a-massive-scale-up-in-investment-in-mental-health

Williams B, King C, Shannon B, Gosling C (2021) Impact of COVID-19 on paramedicine students: a mixed methods study. Int Emerg Nurs 56:100996. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ienj.2021.100996

Williams B, Beovich B, Olaussen A (2021) The definition of paramedicine: an international delphi study. J Multidiscip Healthc 14:3561–3570. https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S347811

Wills HL, Asbury EA (2019) The incidence of anxiety among paramedic students. Australasian J Paramed 16:1–6. https://doi.org/10.33151/ajp.16.649

Wu T, Jia X, Shi H, Niu J, Yin X, Xie J, Wang X (2021) Prevalence of mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 281:91–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.11.117

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate all the respected researchers whose work was included in our reviews.

Funding

This research was funded by King Saud University in Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Adnan Alzahrani (A.A.), Chris Keyworth (C.K.), and Judith Johnson (J.J.) were responsible for designing and implementing the research, analysing the results, and writing the manuscript. Khalid Mufleh Alshahrani(K.A.) and Rayan Alkhelaifi(R.A.) assisted in study design, screening and data extractions and critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study as a review had no participants. Yet the review as a protocol was registered in the PROSPERO International Register of Systematic Reviews (Registration No: CRD42022303570).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendices

Appendix

Appendix: 1E Meta-analysis table for PTSD studies

Appendix: 1C Funnel plot for PTSD studies

Appendix: 1F Data extraction PTSD

SN | Study/Year | Country | Scalea | Research design | Sample size all/Paramedic students | Sampling method | Gender/mean Age | Prevalence rate (%) | Mean | SD | SE | Effect size weighted average prevalence (%) | CI | Q between subgroup tests p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1 | [16] | South Africa | Davidson trauma scale (DTS) | Cross-sectional | 130 | Non random | M.84(63.6) F.48(36.4) /22 | 16% | 1.18 | N/A | 0.11 | Unavailable | 95% 0.93–1.43 | N/A |

2 | McKinnon et al [37] | United Kingdom | Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) | Mix method longitudinal | 89 | Opportunistic sampling method | M.33(38.2%) F.55(61.8%) /26 | 16.8%(N = 15)–20.2%(N = 18) | B15.52/ F15.39 | B16.1/ F15.8 | B. 0.08 | 0.45*** | [0.48–0.81[ | p < 0.001 |

3 | [34] | Australia | Posttraumatic Stress Diagnostic Scale (PDS) | Cross-sectional | 42 | Non random | M.35 F. 7/ 35 | 5% 17% mild | 3.81 | 4.41 | (0.08) | Unavailable | Unavailable | N/A |

4 | Mehta et al. 2021 | Australia | Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) | longitudinal | 80 | Non random | M.15(38.5) F.48(61.5) /23 | N/A | B16.82/ F12.82 | N/A | 2.28/2.27 | Unavailable | Unavailable | N/A |

5 | [39] | Australia | 1- The Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5(PCL-5) 2- The Posttraumatic Growth Inventory X | Pilot study | 47 | Non random | M.28 (59.6) F.18 (38.3) Intersex 1 (2.1)/ 23 | 1. 17.02% | 1–16.81 2- 72.4 | n/a | 1- 2.14 2- 4.28 | Unavailable | Unavailable | N/A |

6 | [22] | Canada | Davidson trauma scale(DTS) | Cohort | 13(6 done PTSD) | Convenience sample | M.8(38.5) F.5(61.5)/25 | 16.6% | 7.77 | 11.35 | N/A | Unavailable | unavailable | n/a |

7 | [21] | USA | The Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PK) scale | Cohort/ Dissertation | 225/105 | Convenience sample | M.93 F.12/27 | 21.9% | N/A | N/A | N/A | Unavailable | Unavailable | ps < 0.0001 |

Appendix 2E Meta-analysis table for anxiety studies

Appendix: 2C Funnel plot for anxiety studies

Appendix: 2F Data extraction anxiety

SN | Study/Year | Country | Research design | Scalea | Sample size all/Paramedic students | Sampling method | Gender/Mean Age | Prevalence rate (%) | Mean | SD | SE | Effect size weighted average prevalence (%) | CI | Q between subgroup tests p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1 | McKinnon et al. [37] | UK | Mix methods Longitude | GAD7 | 89 | Opportunistic sampling method | M.33(38.2%) F.55(61.8%) /26.36 | Mild:30% 27% | B.6.25 f.6.12 | 5.23 5.2 | 0 | n/a | Unavailable | N/A |

2 | Williams et al. [13] | AU | Mix methods | GAD7 | 151 | Convenience sample | M: 36 (23.8) F: 113 (74.8) Prefer NTS: 2 (1.3) /n/a | 35% mild 27% | 7.67 | 4.85 | Unavailable | Unavailable | Between gender 95% CI: (1.02, 4.12) | Between gender p = 0.045 |

3 | [56] | New Zealand | Mix methods | WTA | 117 | All students/ census method | M.43 F. 82 gender diverse. 1/ 20–29 | 70% | 33.76 | ± 7.23 | Unavailable | N/A | Unavailable | N/A |

4 | [22] | Canada | Cohort | STAI & TAI | 13 | Convenience sample | M.8(38.5) F.5(61.5)/25 | 13/16 = 81% 15/16 = 94% Moderate and higher Sever 19% 31% | 44.77 49.54 | 8.08 7.29 | Unavailable | N/A | Unavailable | N/A |

5 | [6] | KSA | Cross-sectional | GAD7 | 181 | All students/ census method | M. 133 (79.2%) F. 48 (75%) /22 | 21%m 33%f Both = 24.3% | Unavailable | N/A | Unavailable | N/A | ||

6 | [51] | Turkey | Cross-sectional | TAI | 185/108 | Random sampling | M. 108 (100%) F. 0(0%)/ 20y/o | 37.1% | 34.02 | 5.45 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.07 |

7 | [32] | Tunisia | Cross-sectional | DASS21 | 366/114 | Convenience sample | M. 22 (6%) F. 344 (94%) / n/a | 91.2% | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Appendix 3E Meta-analysis table for Depression studies

Appendix: 3C Funnel plot for depression studies

Appendix: 3F Data extraction depression

SN | Study/Year | Country | Research design | Scale | Sample size all/Paramedic students | Sampling method | Gender/Mean Age | Prevalence rate (%) | Mean | SD | SE | Effect size weighted average prevalence (%) | CI | Q between subgroup tests p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1 | [16] | South Africa | Cross-sectional | CES-D | 130 | Non random | M.84(63.6) F.48(36.4) /22 | 28% | 1.245 Odds ration.1.23 | Unavailable | 0.07 | Unavailable | 1.07–1.42 | N/A |

2 | McKinnon etal. 2021 | UK | Mix methods Longitudinal | PHQ-9 | 89 | Opportunistic sampling method | M.33(38.2%) F.55(61.8%) /26 | 30%(32% mild) | B. 6.73 F.6.39 | B. 5.76 F.5.23 | Unavailable | Unavailable | N/A | N/A |

3 | Mehta et al. 2021 | AU | Longitudinal | K10(for distress) | 78 39 b + f | Non random | M.15(38.5) F.48(61.5) /23 | 43.6% | B.18.77 F.18.69 | Unavailable | 1.1 1.05 | Unavailable | N/A | N/A |

4 | [8] | Iran | Descriptive-correlative study | (BDI-II) | 119/9 | Convenient sampling | n/a | 22% | Unavailable` | Unavailable | Unavailable | N/A | N/A | |

5 | [22] | Canada | Cohort | BDI | 41/13 | Convenience sample | M.8(38.5) F.5(61.5)/25 | 8% | 4.46 | 3.4 | Unavailable | Unavailable | N/A | N/A |

6 | [32] | Tunisia | Cross-sectional | DASS21 | 366/114 | Convenience sample | M. 22 (6%) F. 344 (94%)/ n/a | 56.2% | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alzahrani, A., Keyworth, C., Alshahrani, K.M. et al. Prevalence of anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder among paramedic students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-024-02755-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-024-02755-6