Abstract

Associative learning is key to how bees recognize and return to rewarding floral resources. It thus plays a major role in pollinator floral constancy and plant gene flow. Honeybees are the primary model for pollinator associative learning, but bumblebees play an important ecological role in a wider range of habitats, and their associative learning abilities are less well understood. We assayed learning with the proboscis extension reflex (PER), using a novel method for restraining bees (capsules) designed to improve bumblebee learning. We present the first results demonstrating that bumblebees exhibit the memory spacing effect. They improve their associative learning of odor and nectar reward by exhibiting increased memory acquisition, a component of long-term memory formation, when the time interval between rewarding trials is increased. Bombus impatiens forager memory acquisition (average discrimination index values) improved by 129% and 65% at inter-trial intervals (ITI) of 5 and 3 min, respectively, as compared to an ITI of 1 min. Memory acquisition rate also increased with increasing ITI. Encapsulation significantly increases olfactory memory acquisition. Ten times more foragers exhibited at least one PER response during training in capsules as compared to traditional PER harnesses. Thus, a novel conditioning assay, encapsulation, enabled us to improve bumblebee-learning acquisition and demonstrate that spaced learning results in better memory consolidation. Such spaced learning likely plays a role in forming long-term memories of rewarding floral resources.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The ability of bumblebees (Hymenoptera, Apidae, Bombini) to associatively learn that certain flowers provide nectar rewards is essential to their role as keystone pollinators in a wide variety of ecosystems ranging from the Arctic to the tropics (Goulson 2003). Raine and Chittka (2008) demonstrated that learning speed is correlated with foraging success: colonies that learn faster achieve greater fitness. Bumblebees are therefore adept at learning cues such as color (Dukas 1995; Gumbert 2000), floral morphology (Chittka et al. 1999; Laverty 1994), and odor (Spaethe et al. 2007), an ability which they share with pollinators like honeybees (Menzel et al. 2001) and stingless bees (McCabe et al. 2007).

Honeybees are the main model for pollinator associative learning (Dukas 2008) but have a different foraging biology, relying more upon group foraging than individual discovery (Dornhaus and Chittka 2004). They also occupy more restricted habitats than bumblebees (temperate to tropical, Michener 2000). Thus, understanding bumblebee associative learning will allow us to apply a comparative approach to understand how evolution has shaped pollinator learning in animals with different life histories in a broad range of ecosystems.

Honeybee memory acquisition and retention are strongly influenced by the spacing effect (Menzel et al. 2001), a phenomenon in which longer delays between learning bouts result in stronger associative learning (Ebbinghaus 1885, Dempster 1989). This is also known as the trial spacing effect (Deisig et al. 2007), or distributed learning (Litman and Davachi 2008), and has been observed in a wide range of species, including pigeons (Bizo and White 1994), monkeys (Riopelle and Addison 1962), humans (Grant et al. 1952), and moths (Fan et al. 1997). To date, no studies have determined whether bumblebees exhibit the memory spacing effect.

Studies of honeybee and bumblebee associative learning generally employ a standard learning assay, the proboscis extension reflex (PER, Bhagavan and Smith 1997; Erber et al. 1998; Laloi and Pham-Delegue 2004; Laloi et al. 1999; Menzel et al. 2001; Riddell and Mallon 2006). In this assay, bees are restrained inside holders and presented with sugar solution (unconditioned stimulus, US) which elicits proboscis extension (unconditioned response) that can be paired with a cue such as odor (conditioned stimulus, CS+, Bitterman et al. 1983). Following successful conditioning, subsequent presentations of the CS+ will elicit the PER in the absence of the US. The time between CS+ presentations is the inter-trial interval (ITI). However, the classic PER assay, originally designed for honeybees, has not led to high rates of learning (maximum of 44% and 27.8% correct PER responses, respectively) in the pioneering bumblebee studies of Laloi et al. (1999) and Laloi and Pham-Delegue (2004). For comparison, honeybee olfactory PER increases to ≥60% correct responses after a single learning trial and ≥80% after multiple trials (Menzel and Müller 1996). This may be due to inherent differences in honeybee and bumblebee-learning ability. It is also possible that a modified assay, tailored to bumblebees, could improve learning. We therefore designed a novel conditioning bioassay to determine if the memory spacing effect occurs in the acquisition of bumblebee associative learning.

Materials and methods

Colonies and study site

We sequentially used five lab-reared colonies of Bombus impatiens Cresson obtained from Biobest Biological Systems (Ontario, Canada) in a temperature-controlled room (21°C) at the University of California San Diego, La Jolla, California, USA (32°52.690′N, 117°14.464′W). Each colony contained approximately 100–200 individuals. This species is found in the Eastern United States and Canada, ranging from Ontario and Maine to Florida and west to Michigan, Illinois, Kansas, and Mississippi (Heinrich 1979). We housed the bees in a wood nest box (32.5 × 28.4 × 15 cm with an opaque cover) and allowed them to feed in a foraging arena in which foragers could also fly. The arena consisted of a clear plastic box (32 × 54 × 27 cm) with a clear plastic lid and one mesh panel (25.5 × 21 cm) on top to allow ventilation. Colonies were exposed to a 12-h light cycle (20-W halogen bulb). We fed the colonies in the foraging arena with 0.5 M sucrose solution and fresh pollen provided ad libitum in small plastic dishes. We individually marked each forager (defined in our study as a bee that fed twice in the foraging arenas within 15 min) on the thorax with different colors of acrylic paint.

Harnesses versus capsules

We used bees from two growing colonies (c1 and c2) and individually captured bees with plastic vials as they collected 0.5 M sucrose solution. After capture, we chilled foragers on ice until movement had significantly decreased (approximately 3 min), then weighed, and placed each bee in a harness or capsule (described below). We incubated restrained bees for 5 h at 37°C and 57% humidity to increase their receptiveness to sugar solution. The conditioning environment was inside a fume hood to quickly remove odors and in a room maintained at 20°C and 60% humidity. We returned bees back to the foraging arena after the experiment to avoid depleting the colony of foragers. We did not reuse the same foragers in subsequent trials.

In pilot trials, harnessed B. impatiens foragers exhibited minimal PER responses. Our harnesses followed the design for honeybee PER experiments but were larger to accommodate bumblebees (Laloi et al. 1999). We placed each bee inside a 1.3-cm diameter stainless steel tube and restrained her with a strip of cloth tape (Fig. 1a). In this harness, foragers spent most of their time struggling to escape, and few responded with proboscis extension when we tapped their antennae with sucrose solution.

a Diagrams of the traditional proboscis extension reflex harness and (b–f) photos of the capsule conditioning apparatus (medium-sized capsules shown, some capsules were slightly longer or shorter to fit larger and smaller bees). A vertical bar indicates 1 cm in each image. The capsule images show (b) a chilled, inactive bee placed inside one half of the capsule with the cap ready for attachment (note the Petri dish stand), (c) a front view with the bee after she has been trained to the CS+ and is extending her proboscis in response to the CS+, (d) a side view showing the proboscis extension and illustrating how the cloth tape holds both sides of the capsule together, (e) a close-up view of the capsule with the bee’s head partially extended through the front hole and proboscis extended, and (f) a close-up view of the capsule rear section showing the hole through which odors exited the capsule (the dark mass of the bee’s abdomen is partially visible)

We therefore designed a new type of restraint (capsules) and compared the efficacy of associative learning in harnesses and in capsules. Each capsule was made from two 1.8-ml plastic test tubes (12.4 mm outer diameter, 10.5 mm inner diameter, NUNC cryotube, Waltham, MA, USA, Fig. 1b). We made half of the capsule by cutting the cryotube to an average length of 2.0 cm (some lengths were longer or shorter as necessary to insure a good fit between bee and capsule) and drilling a 0.5-cm diameter hole into the base. This hole size allowed us to insert a pipette tip to contact the bee’s antennae but did not allow her to escape. The second cryotube served as a cap and was cut to a length of 0.75 cm with a 0.5-cm diameter hole drilled into its base (Fig. 1b). These holes allowed odor to flow through the assembled capsule. We placed the bee inside half of the capsule and held both halves together with a strip (3 mm wide) of cloth tape (Fig. 1c, d). The assembled capsule was then placed on a stand, a small plastic Petri dish lid (4.5 cm diameter, Fig. 1c). Once conditioned, a forager would extend her proboscis through a capsule hole in response to the CS+ (Fig. 1e).

We tested the effect of restraint type on memory acquisition by randomly assigning foragers to conditioning in harnesses or capsules. To generate odor, we pipetted 20 ml of lemon odor (McCormick, Hunt Valley, MD, USA) onto Whatman filter paper and delivered the odor using an Eppendorf syringe (model number 0030 048.024, Hamburg, Germany) at a rate of 1.25 ml/s. In the conditioned odor trials, we delivered lemon-scented air for 10 s and then presented lemon-scented air for another 10 s while simultaneously feeding the bee 1 µl of 2.5 M sucrose solution after tapping her on the antennae to elicit proboscis extension (Fig. 2a). In unconditioned trials, we controlled for the mechanosensory effect of the CS+ airstream by presenting odorless air (clean syringe, 1.25 ml/s) for 10 s and then simultaneously presented odorless air and a sham touch to the antenna with a clean pipette tip for 10 s. We recorded the bee’s response during each 10-s period, scoring a complete proboscis extension as a one and no proboscis extension as a zero (protocol adapted from Laloi et al. 1999).

Timeline and results of conditioning with different restraint types. a The timeline shows how a bee was treated during a CS+ followed by a CS− trial (ITI = inter-trial intervals of 7.5 min). We plot results on the same graph to facilitate comparisons of responses to CS+ and CS−. Results of conditioning with (b) traditional proboscis extension reflex (PER) harnesses (n = 40 bees, no bees responded to the CS− during the first eight trials) and (c) capsules (n = 24 bees). The percentage PER response shows the proportion of bees that responded in each trial with proboscis extension during the first 10 s of odor presentation. d Comparison of average discrimination index (DI) responses to different restraint types with bars indicating standard errors. We calculated the DI for each bee by subtracting the number of responses to the CS− from the number of responses to the CS+ over all trials (Pelz et al. 1997). Different letters indicate significantly different responses (p < 0.05)

Bombus impatiens foragers can learn the timing of nectar availability in flowers offering high quality artificial nectar (Boisvert et al. 2007). To remove the potential timing effect and study olfactory learning alone, we ran rewarded and unrewarded trials in the pseudorandom order ABBABAABABBABAABABBA (20 trials per bee) with A being an conditioned trial (CS+) and B being a unconditioned trial (CS−, Bitterman et al. 1983) and with an ITI of 7.5 min (to facilitate data comparison with Laloi et al. 1999).

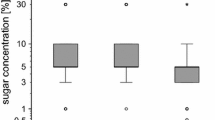

Testing the effect of ITI

To test the memory spacing effect, we used four growing bumblebee colonies (c2–c5) in the same environment, capturing and conditioning foragers as previously described. We only used capsules to condition bees. Two odors, lemon or anise, were used to ensure the response was not odor-specific. One odor was randomly assigned to be the conditioned odor (CS+) while the other was used as the unconditioned odor (CS−) in same trial order as the first experiment. For half of the bees, lemon odor was the CS+. For the other half, anise odor was the CS+. Honeybee studies on the memory spacing effect examine memory consolidation on a time scale of 30 s to 10 min (Deisig et al. 2007; Menzel et al. 2001). We used delays within this range (1, 3, and 5 min) to study the effect of ITI in bumblebees. In our experiment, each individual was only rewarded after exposure to a single “floral type” (one floral odor). We therefore examined how memory of a flower type can be enhanced, not how delays between rewards affect forager choice among different rewarding flower types.

Statistics

To ensure that we analyzed responses due to learning the conditioned odor, we used a discrimination index (DI, Pelz et al. 1997) calculated as the difference, per bee, between the sum of her responses to the CS+ and CS− over all trials. Thus, a forager displaying a PER response in seven CS+ trials and in two CS− trials would have a DI of five, and a forager who responded to all CS+ and CS− trials would have a DI of zero. The null hypothesis is that the bee does not preferentially extend her proboscis to CS+ over CS− (DI = 0). In general, we scored very few responses to the CS− (Figs. 2 and 3) but use the DI to provide a standardized measure of learning. Our data met all criteria for analysis of variance (ANOVA) on dichotomous data (0 or 1 PER scoring, Lunney 1970). We therefore ran one-tailed t tests (t) to determine if the DI is significantly greater than zero (JMP v5.1, SAS Software, Cary, NC, USA). We performed ANOVA and mixed-model analysis (using expected mean squares analysis to estimate the proportion of model variance explained by colony as a random effect). To determine if the slopes of the learning curves (as modeled by standard least squares regression) for the different ITI are unequal, we tested for a significant interaction of ITI and trial number (Sokal and Rohlf 1981). Effects of different ITI treatments were compared using post hoc Tukey–Kramer honestly significant difference tests (Q). We report averages as mean ± 1 standard error.

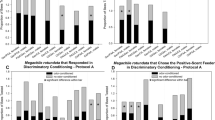

Results of conditioning with different inter-trial intervals (ITI) durations. a The percentage proboscis extension reflex response shows the proportion of bees that responded in each CS+ trial and each CS− with proboscis extension during the first 10 s of odor presentation for ITI treatments of 1 min (n = 27), 3 min (n = 27), and 5 min (n = 28). Odorant type had no effect and, thus, the CS+ and CS− responses to both odors were pooled and shown. b Comparison of average responses to different ITI treatments with bars indicating standard errors. We calculated the discrimination index for each bee by subtracting the number of responses to the CS− from the number of responses to the CS+ over all trials (Pelz et al. 1997). Different letters indicate significantly different responses (p < 0.05)

Results

Harnesses versus capsules

There is a significant effect of restraint type on learning (effect test F 1,60 = 95.28, p < 0.0001), but no effect of colony (effect test F 1,60 = 0.70, p = 0.41; full model F 2,60 = 12.01, p < 0.0001). We therefore pooled data from both colonies in subsequent analyses. Bees conditioned using harnesses showed relatively little learning (Fig. 2b, d). The majority of harnessed bees continually struggle to escape even after the 5-h incubation period, and only 5% exhibited the PER to the CS+ in the tenth trial. The mean DI (0.13 ± 0.11) was not significantly greater than zero (t 23 = 1.14, p = 0.133).

In contrast, bees within capsules (Fig. 1c) rapidly acclimated and extended their proboscises when tapped on the antennae with sugar solution. Bees conditioned inside capsules showed a higher level of odor learning: the response plateau was 51% (Fig. 2c, d). Encapsulated bees had a mean DI (2.93 ± 0.44) that was significantly greater than zero (t 39 = 2.93, p < 0.0001). We therefore used capsules to test the effect of ITI.

Effect of ITI

We first analyzed the effect of rewarded odor type, ITI duration, and colony identity (a random effect) on DI. There is no significant interaction of rewarded odor type and ITI duration (interaction effect test: F 1,77 = 0.10, p = 0.75) and we therefore ran a three-factor EMS model (F 5,78 = 2.80, p = 0.02) in which the only significant factor was ITI duration (ITI effect test: F 1,78 = 7.34, p = 0.008). There is no significant effect of rewarded odor type (effect test F 1,78 = 0.67, p = 0.41) or colony identity (effect test F 3,78 = 2.24, p = 0.09). Thus, there is a significant memory spacing effect, and it is not affected by the colony or type of rewarded odor used.

We therefore pooled the results for different odors and colonies in subsequent analyses. Bees in the 1-min ITI treatment group learned to associate odor with the reward, reaching a response plateau of 32% (Fig. 3a). They showed a mean DI (1.36 ± 0.43) that is significantly greater than zero (t 27 = 3.17, p = 0.002). Bees in the 3-min ITI treatment group were also able to successfully associate the conditioned odor with the reward, reaching a response plateau of 50%. These bees showed a higher mean DI (2.25 ± 0.45) that is significantly greater than zero (t 27 = 5.03, p < 0.0001, Fig. 3b). Finally, bees in the 5-min ITI had the highest mean DI (3.11 ± 0.513, significantly greater than zero t 26 = 6.07, p < 0.0001, Fig. 3c), reaching a response plateau of 59%. Post hoc analysis shows that the 1-min ITI results in significantly less associative learning than the 5-min ITI (Q = 2.39, p < 0.05, Fig. 3d).

There is an effect of ITI on learning rate. The learning slopes for different ITI treatments are significantly different: CS+ responses pooled by ITI (Fig. 3a) show a significant interaction between trial number and ITI (interaction effect test: F 2,24 = 4.01, P = 0.03). The learning curve slopes (Fig. 3a) are, respectively, 3.2, 5.3, and 6.7 CS+ PER responses per learning trial for 1, 3, and 5 min ITI (linear regressions: R 2 ≥ 0.70, F 1,8 ≥ 18.4, P ≤ 0.003).

Discussion

These data provide the first strong evidence for the memory spacing effect in bumblebees. With increasing ITI from 1 to 5 min, learning acquisition in B. impatiens significantly improved. Thus, bumblebees share a memory spacing effect similar to that exhibited by honeybees and a wide variety of vertebrate species (Bizo and White 1994; Riopelle and Addison 1962; Menzel et al. 2001). To test the memory spacing effect, we developed a method of containing bees (capsules) that facilitates a significantly higher rate of learning in bumblebees than classical harness restraints. Such capsules could be useful for species that do not respond well to harnesses developed for honeybee PER experiments. We did not find significant intercolony variation in the olfactory learning acquisition of B. impatiens, although Bombus terrestris audax Linnaeus foragers from different colonies exhibited significant variation in their visual learning abilities (Raine et al. 2006).

Effect of harness type

Honeybee-type harnesses (Fig. 1a) resulted in very low PER responses to the conditioned odor (a maximum of 5% of foragers responded with PER at least once after nine training trials). Most harnessed B. impatiens foragers constantly struggled to escape and may thus have been distracted from learning or have been too stressed to learn. This could result from tube harnesses (Fig. 1a) whose diameters were too large. However, we observed the same struggling in all tube harnesses, even those that provided a snug fit. Moreover, all capsules had the same diameter (Fig. 1b), differed only in length, and yet resulted in much higher levels of learning acquisition. Boisvert and Sherry (2006) allowed a B. impatiens forager to enter a foraging chamber in which she was further confined within a small space near the food source. Under these conditions, bumblebees also exhibited high levels of proboscis extension, with 35% of bees responding to the CS+ after only one learning trial (Fig. 2c). Foragers may respond well to such confinement because it simulates the natural situation of being partially enclosed by floral structures while collecting nectar.

Associative learning assays can be quite sensitive to the precise methodologies used (Menzel and Müller 1996). With this caveat in mind, it is still interesting to compare our results with those obtained from other bumblebee studies. B. impatiens foragers conditioned in our capsules exhibited a percent PER plateau of 39–63% as compared to 16.7–44% (B. terrestris, Laloi and Pham-Delegue 2004; Laloi et al. 1999) or 20–27% (PER response of B. terrestris control bees injected with a control Ringer solution, Riddell and Mallon 2006). We suggest that encapsulation may therefore provide a useful technique to explore associative learning in bumblebees.

Effect of ITI

Forager memory acquisition (average DI) improved by 129% and 65% at ITI of 5 and 3 min, respectively, as compared to an ITI of 1 min. This increase in short-term learning from increased ITI may plateau after 5 min. The maximum percentage conditioned PER response was slightly higher in the 5-min ITI (63%) than in the 7.5-min ITI (54%), although intervals come from experiments in which different types of CS− stimuli were used and are thus difficult to compare. Lower memory acquisition for shorter ITI (Fig. 3a, b) may reflect a lack of memory consolidation between trials, perhaps due to interference between consecutive consolidation processes (Menzel et al. 2001).

Bumblebee foraging can likewise be examined at different time scales. Flight times between flowers ranged from 2–6 s in four species of European bumblebees in a natural reserve near Berlin, Germany (Raine and Chittka 2007). At this time scale, delays between floral rewards influence floral constancy. However, there is a longer time period during which bees travel to the nest, deposit food, and return to the food patch. We call this the inter-foraging bout delay, a larger-scale time delay that is in the range of the memory spacing effect.

Inter-foraging bout delays could be subject to a broad variety of seasonal and habitat-specific intra- and extranidal factors that make bumblebees, with their extensive geographic and climate range, particularly interesting. Could their memory consolidation rates (and thus optimum ITI) be tuned, within certain restrictions, to different environments? It is also relevant to determine if long-term memories can be activated by floral odors brought back to the nest or if odor-rewarded experiences gained in the nest during recruitment can facilitate subsequent learning (Mc Cabe and Farina 2009). Honeybee foragers can retrieve long-term olfactory memories of rewarding food (formed at least 2 h previously) and leave the nest to find this food when the rewarding odor is introduced in the nest (Reinhard et al. 2004). B. terrestris foragers can be activated to forage for the odor brought back by a successful forager when the colony is tested with the same rewarding odor over multiple trials (Dornhaus 1999; Dornhaus and Chittka 1999). In B. impatiens, Renner and Nieh (2008) tested the effect of short-term changes in rewarding odors. They exposed each colony to three different reward odors randomly presented over multiple trials, with only one reward odor per trial. Activated nestmates preferred the odor brought back by a successful forager for only one of the three odor types, perhaps because the rewarded odor changed on a near-daily basis. Recently, Molet et al. (2009) demonstrated that releasing floral scent inside a B. terrestris colony was sufficient to trigger learning. This learning is further enhanced if learned odors are contained in stored food. Thus, intra- or extranidal experiences with the same rewarding food type could play a role in foraging activation, particularly if foraging experiences spread out over time contain more reliable information (Menzel et al. 2001) worth storing in long-term memory.

References

Bhagavan S, Smith BH (1997) Olfactory conditioning in the honey bee, Apis mellifera: effects of odor intensity. Physiol Behav 61:107–117

Bitterman ME, Menzel R, Fietz A, Schafer S (1983) Classical conditioning of proboscis extension in honeybees (Apis mellifera). J Comp Psychol 97:107–119

Bizo LA, White KG (1994) Pacemaker rate in the behavioral theory of timing. J Exp Psychol Anim Behav Processes 20:308–321

Boisvert MJ, Sherry DF (2006) Interval timing by an invertebrate, the bumble bee Bombus impatiens. Curr Biol 16:1636–1640

Boisvert MJ, Veal AJ, Sherry DF (2007) Floral reward production is timed by an insect pollinator. Proc Biol Sci 274:1831–1837

Chittka L, Thomson JD, Waser NM (1999) Flower constancy, insect psychology, and plant evolution. Naturwissenschaften 86:361–377

Deisig N, Sandoz JC, Giurfa M, Lachnit H (2007) The trial-spacing effect in olfactory patterning discriminations in honeybees. Behav Brain Res 176:314–322

Dempster FN (1989) Spacing effects and their implications for theory and practice. Educ Psychol Rev 1:309–330

Dornhaus, A (1999) Communication about food sources in bumble bees—do bumble bees show a behavior that is ancestral to the honeybees’ dance? Diploma Thesis, University of Würzburg, Würzburg

Dornhaus A, Chittka L (1999) Evolutionary origins of bee dances. Nature 401:38

Dornhaus A, Chittka L (2004) Information flow and foraging decisions in bumble bees (Bombus spp.). Apidologie 35:183–192

Dukas R (1995) Transfer and interference in bumblebee learning. Anim Behav 49:1481–1490

Dukas R (2008) Evolutionary biology of insect learning. Annu Rev Entomol 53:145–160

Ebbinghaus H (1885) Memory. Teacher’s College, New York

Erber J, Kierzek S, Sander E, Grandy K (1998) Tactile learning in the honeybee. J Comp Physiol A 183:737–744

Fan RJ, Anderson P, Hansson B (1997) Behavioural analysis of olfactory conditioning in the moth Spodoptera littoralis (Boisd.) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). J Exp Biol 200:2969–2976

Goulson D (2003) Effects of introduced bees on native ecosystems. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst 34:1–26

Grant DA, Schipper LM, Ross BM (1952) Effect of intertrial interval during acquisition on extinction of the conditioned eyelid response following partial reinforcement. J Exp Psychol 44:203–210

Gumbert A (2000) Color choices by bumble bees (Bombus terrestris): innate preferences and generalization after learning. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 48:36–43

Heinrich B (1979) Bumblebee economics. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Laloi D, Pham-Delegue MH (2004) Bumble bees show asymmetrical discrimination between two odors in a classical conditioning procedure. J Insect Behav 17:385–396

Laloi D, Sandoz JC, Picard-Nizou AL, Marchesi A, Pouvreau A, Tasei JN, Poppy G, Pham-Delegue MH (1999) Olfactory conditioning of the proboscis extension in bumble bees. Entomol Exp Appl 90:123–129

Laverty TM (1994) Bumble bee learning and flower morphology. Anim Behav 47:531–545

Litman L, Davachi L (2008) Distributed learning enhances relational memory consolidation. Learn Mem 15:711–716

Lunney GH (1970) Using analysis of variance with dichotomous dependent variables: an empirical study. J Educ Meas 7:263–269

Mc Cabe SI, Farina WM (2009) Odor information transfer in the stingless bee Melipona quadrifasciata: effect of in-hive experiences on classical conditioning of proboscis extension. J Comp Phys A 195:113–122

McCabe SI, Hartfelder K, Santana WC, Farina WM (2007) Odor discrimination in classical conditioning of proboscis extension in two stingless bee species in comparison to Africanized honeybees. J Comp Physiol A 193:1089–1099

Menzel R, Müller U (1996) Learning and memory in honeybees: from behavior to neural substrates. Annu Rev Neurosci 19:379–404

Menzel R, Manz G, Menzel R, Greggers U (2001) Massed and spaced learning in honeybees: the role of CS, US, the intertrial interval, and the test interval. Learn Mem 8:198–208

Michener CD (2000) The bees of the world. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore

Molet M, Chittka L, Raine NE (2009) How floral odours are learned inside the bumblebee (Bombus terrestris) nest. Naturwissenschaften 96:213–219

Pelz C, Gerber B, Menzel R (1997) Odorant intensity as a determinant for olfactory conditioning in honeybees: roles in discrimination, overshadowing and memory consolidation. J Exp Biol 200:837–847

Raine NE, Chittka L (2007) Flower constancy and memory dynamics in bumblebees (Hymenoptera: Apidae: Bombus). Entomol Gen 29:179–199

Raine NE, Chittka L (2008) The correlation of learning speed and natural foraging success in bumble-bees. Proc Biol Sci 275:803–808

Raine NE, Ings TC, Ramos-Rodriguez O, Chittka L (2006) Intercolony variation in learning performance of a wild British bumblebee population (Hymenoptera: Apidae: Bombus terrestris audax). Entomol Gen 28:241–256

Reinhard J, Srinivasan MV, Guez D, Zhang SW (2004) Floral scents induce recall of navigational and visual memories in honeybees. J Exp Biol 207:4371–4381

Renner M, Nieh JC (2008) Bumble bee olfactory information flow and contact-based foraging activation. Insectes Soc 55:417–424

Riddell CE, Mallon EB (2006) Insect psychoneuroimmunology: immune response reduces learning in protein starved bumblebees (Bombus terrestris). Brain Behav Immun 20:135–138

Riopelle AJ, Addison RG (1962) Temporal factors in pattern discrimination by monkeys. J Comp Physiol Psychol 55:926–930

Sokal RR, Rohlf FJ (1981) Biometry, 2nd edn. W. H Freeman and Company, New York

Spaethe J, Brockmann A, Halbig C, Tautz J (2007) Size determines antennal sensitivity and behavioral threshold to odors in bumblebee workers. Naturwissenschaften 94:733–739

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Elinor Lichtenberg for her comments and help with data analysis and the anonymous reviewers whose comments have substantially improved this paper. This research was supported by the UCSD Chancellor’s Research Scholarship and by the ORBS (Opportunities for Research in the Behavioral Sciences) Program sponsored by NSF Grants IBN 0503468 and IBN 0545856.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Toda, N.R.T., Song, J. & Nieh, J.C. Bumblebees exhibit the memory spacing effect. Naturwissenschaften 96, 1185–1191 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00114-009-0582-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00114-009-0582-1