Abstract

Purpose

Trauma team activation (TTA) is thought to be essential for advanced and specialized care of very severely injured patients. However, non-specific TTA criteria may result in overtriage that consumes valuable resources or endanger patients in need of TTA secondary to undertriage. Consequently, criterion standard definitions to calculate the accuracy of the various TTA protocols are required for research and quality assurance purposes. Recently, several groups suggested a list of conditions when a trauma team is considered to be essential in the initial care in the emergency room. The objective of the survey was to post hoc identify trauma-related conditions that are thought to require a specialized trauma team that may be widely accepted, independent from the country’s income level.

Methods

A set of questions was developed, centered around the level of agreement with the proposed post hoc criteria to define adequate trauma team activation. The participants gave feedback before they answered the survey to improve the quality of the questions. The finalized survey was conducted using an online tool and a word form. The income per capita of a country was rated according to the World Bank Country and Lending groups.

Results

The return rate was 76% with a total of 37 countries participating. The agreement with the proposed criteria to define post hoc correct requirements for trauma team activation was more than 75% for 12 of the 20 criteria. The rate of disagreement was low and varied between zero and 13%. The level of agreement was independent from the country’s level of income.

Conclusions

The agreement on criteria to post hoc define correct requirements for trauma team activation appears high and it may be concluded that the proposed criteria could be useful for most countries, independent from their level of income. Nevertheless, more discussions on an international level appear to be warranted to achieve a full consensus to define a universal set of criteria that will allow for quality assessment of over- and undertriage of trauma team activation as well as for the validation of field triage criteria for the most severely injured patients worldwide.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Major trauma is one of the leading causes of death all over the world [1]. To improve basic trauma care worldwide, a trauma checklist has been suggested by the WHO [2]. Advanced trauma care requires a pre-hospital rescue system and a network of trauma centers so that the right patient will be brought to the right initial medical care or can be transferred to the right hospital in the least possible time.

Trauma team activation (TTA) is thought to be essential for the delivery of advanced and specialized care to very severely injured patients. Field triage is intended to allow pre-hospital emergency medical care providers to identify such patients and to trigger TTA at an early time point to get personal and equipment at the resuscitation room ready—at best before the arrival of the patient at the hospital [3].

However, these instruments have been the focus of an ongoing debate regarding over- and under-utilization of hospital resources [4,5,6], because the more sensitive the TTA criteria are, the more overtriage (i.e. number of patients that fulfill TTA criteria without having a true medical need) results and the higher the likelihood that the trauma team is activated for patients that neither require nor benefit from the activation. On the other hand, triage criteria with low sensitivity and low specificity may produce considerable undertriage by missing patients who urgently require being treated by a trauma team, but who were not identified [7,8,9,10,11]. Undertriage is undesirable because it may result in avoidable death and morbidity. Thus, it seems sensible to monitor the accuracy of TTA criteria [6]. Up to the present, a wide and largely varying composition of criteria and definitions have been used to describe correct TTA between studies or to calculate undertriage [12,13,14,15,16]. To suggest a generally acceptable standard to identify patients who, in retrospect, will have or would have correctly benefited from TTA a list of 20 items has been proposed by traumatologists in Germany and Switzerland in a previous publication [17]. They could be used as a gold standard by which to establish the ‘accuracy’ of field triage criteria in identifying patients who benefitted from highest level trauma team activation. It has to be emphasized that these criteria are intended as an academic study tool to retrospectively classify patients into those who may have benefitted from TTA and those who may not have. At this stage, this is not an attempt to modify field triage criteria.

These criteria have been developed from the viewpoint of countries with highly developed pre-hospital and hospital trauma systems and the universal validity of these parameters has been challenged by the argument that highly developed trauma systems may not be available in middle- and low-income countries [18, 19]. As a matter of fact, there may be significant differences between countries with different income levels as well as within such countries. These may comprise the availability and organization of a pre-hospital rescue system, the possibility and organization of prenotification of a patient to a hospital, the comprehensive coverage by trauma teams within a hospital and the composition of such a trauma team.

Thus, the suggested list of 20 items may not be generally valid in a more global context. To validate these criteria, we initiated an international survey in high-, middle- and low-income countries. The objective of the survey was to identify trauma-related conditions that are thought to require a specialized trauma team in the different settings that may be widely accepted independent of the country’s income level.

Material and methods

The research question was addressed with a cross-sectional survey design using a web-based and paper-based questionnaire. Potential participants were first contacted by email and asked whether they would agree to participate in the survey. The link to the web-based form as well as a print-out form were sent by email to only those participants who had agreed to participate. By answering the questionnaire, participants gave their consent for further use of the assessed data. The survey responses were not anonymized in the data bank. However, every effort was made not to allow the identification of a participant from the information given in the manuscript. Since the survey did not involve interventions or clinical or patient data, no institutional review board approval was required. The survey was conducted from December 2018 to March 2019. Participating countries/physicians were selected on the basis of personal acquaintances of core group members with physicians entrusted with the care of the seriously injured in these countries as well as personal recommendations of other participants in the survey. The survey participants could be surgeons, trauma surgeons, anesthetists or other specialists involved in the acute care of severely injured patients. For some countries, it could be more than one participant per country. We aimed at a similar distribution between high-, upper-middle-, lower-middle- and low-income countries. Our primary intention was to achieve a high rate of responses rather than as many responders as possible. If we received more than one answer from the same country, we chose to keep all responses in the analysis. The variety of the answers from one country was usually so large that it appeared to reflect different local experiences indicating that in those countries there may not be one universal system in the care of the severely injured.

The questionnaire was constructed based around the proposed 20 standard criteria of correct TTA as suggested in the previous work of the authors [17] (question 12 of the questionnaire, see additional electronic material). Each item could be graded using a three-level rating scale (I agree—I partly agree—I disagree) or denoted as not to be relevant or applicable to one’s setting.

Since the availability, resources and organization of trauma care may significantly differ in the participating countries, additional questions were included in the questionnaire relating to the composition and the availability of trauma teams, the number and qualifications of the trauma team members and data on the equipment in the trauma bay (questions 1, 3–11). Furthermore, information was gathered about the pre-hospital rescue system and the selection of patients due to insurance status within the respective countries (questions 2–2E). Lastly, we assumed that many of the participants of the survey would work predominately in high-level institutions within their countries. Therefore, we also aimed at information regarding the structural facilities in (presumably) lower levels of trauma hospitals within their respective countries (questions 13–20).

The survey was first developed and discussed in two Delphi rounds by the core group of the study. Then, this version of the survey was sent to the participants and they were asked to give feedback on the questionnaire of the survey (e.g. are the questions understandable, are they adequate for the respective setting, are important aspects missing, etc.) and to suggest modifications, improvements or additions. The incoming suggestions for improvement and amendments have been then implemented to finalize the survey questions. Most of the questions and definitions appeared to be self-explanatory and generally applicable. However, two definitions require some explanation. First, the level of a trauma hospital may be denominated differently in different countries. To overcome this, we offered alternative terms that we thought will allow for a comparable classification in the participating countries (e.g. “tertiary or major trauma center/supraregional/highest level” versus “regional trauma center/intermediate level” versus “local or district trauma center/basic level”).

Concerning the type of surgeon who may be part of the trauma team, there may be considerable differences, particularly with respect how to define a trauma surgeon. Therefore, we offered several possibilities to cover the different definitions: Two types of “trauma surgeons”: a general surgeon with extra training in trauma, similar to USA or an orthopedic surgeon with extra training in trauma, like in some European countries. Furthermore, it was possible to choose emergency physician, general or visceral surgeon or orthopedic surgeon.

The online version of the questionnaire was programmed in Google Forms, the print-out form was created in Microsoft Word®. The answers were exported to an Excel® (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, USA) sheet via a CSV file (from the online survey) or manually filled into the Excel® file (from the Word questionnaires). The figures were created using Excel®.

The classification of the country income level followed the World Bank Country and Lending Groups based on the 2017 data [20]. Low-income countries were defined as countries with a gross national income (GNI) per capita, calculated using the World Bank Atlas method, of $995 or less. Lower-middle-income economies was assumed with a GNI per capita of $996 and $3895. Upper-middle-income economies are those with a GNI per capita between $3896 and $12,055. High-income economies are those with a GNI per capita of $12,056 or more.

Results

The survey was sent to physicians in 49 countries with a return rate of 76% (N = 37). Overall, 69 colleagues have been contacted and 51 eventually participated in the survey (74%). The distribution of their country’s income level is detailed in Table 1.

The description of the participating trauma hospitals and the setting in which they work are shown in Table 2. At least two-thirds of the participants classified themselves as of the highest level of care or tertiary care centers, irrespective of the country’s income level. Several regional trauma hospitals and a few local trauma hospitals also participated. The population they served covered the whole range from less than 500,000 to more than 5 million inhabitants. Sixty percent of participating hospitals reported to be the only hospital of this level in their area or city, while 18% were the only hospital of this level within their country. The higher the country’s income level was, the more hospitals were served by an organized pre-hospital rescue system and also more of the severely injured were brought to the hospital by professional ambulances. The vast majority of hospitals had a specially equipped trauma room available and provided a trauma team with the lower-middle-income countries displaying somewhat lower counts. The rate of countries having adopted a system of trauma centers was highest in the middle-income countries.

The agreement with the proposed parameters and conditions for post hoc identification of a situation that would have required a trauma team for the initial care of patients is shown in Table 3. The highest rate of full agreement was observed for “Glasgow coma scale < 9″ (90%) and “respiratory rate < 9 or > 29/min” (90%). The rate of full agreement was more than 75% for “pericardiocentesis”, “advanced airway management”, “pulse oximetry (SpO2) < 90%”, “emergency surgery”, “systolic blood pressure < 90 mmHg”, “shock index > 0.9”, “cardiopulmonary resuscitation”, “deterioration of GCS ≥ 2 points before admission”,” chest tube or needle decompression” and “catecholamine administration”. Eight conditions did not achieve the 75% full agreement level, although their rate of partial agreement was high (12–31%). Overall, the highest rate of agreement was found for abnormal vital functions (respiratory, cardio-circulatory and cerebral dysfunction) and for a number of invasive life-saving procedures to counteract such disturbances. Outcome-related criteria (ICU treatment, death) were rated as less relevant.

Generally speaking, the rate of disagreement with the proposed criteria was very low. In particular, the rate of disagreement was zero for “Glasgow coma scale < 9”, “respiratory rate < 9 or > 29/min”, “advanced airway management”, “pulse oximetry (SpO2) < 90%”, “systolic blood pressure < 90 mmHg” and “shock index > 0.9”. Disagreement was also low (below 5%) for most of the other criteria, except for “transfusion” (6%), “pre-hospital use of a tourniquet” (6%), “radiological therapeutic intervention” (6%), “ICU length of stay > 24 h” (8%) and “death within 24 h” (13%). There was no difference between participants with disagreement with respect to income level (5 low- and lower-middle- vs. 5 upper-middle- and high-income countries), with a trend towards more regional trauma hospitals (6 tertiary vs. 4 regional hospitals) and those without a trauma team (7 with vs. 3 without trauma team).

Only very few respondents indicated that a specific criterion was not relevant to their setting. These participants originated from high-income countries (N = 1), upper-middle-income countries (N = 3), lower-middle-income countries (N = 2) or low-income countries (N = 1) and reported for tertiary care hospitals (N = 6) or regional hospitals (N = 2).

This leaves a rate of partial agreement for the criteria ranging from 6 to 31%. “Abbreviated injury scale (AIS) ≥ 4”, “ICU length of stay > 24 h”, “Transfusion”, “Tourniquet (pre-hospital)” and “Radiological therapeutic intervention” showed the highest rate of partial agreement of more than 25% of participants.

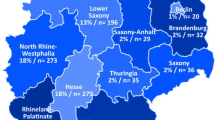

The level of full agreement and of disagreement in the different income levels is shown in Figs. 1 and 2, respectively. The level of full agreement (Fig. 1) was highest in the high and upper-middle-income countries with the majority of criteria reaching 75% or more of full agreement. Some observations deserve mentioning. In high-income countries “shock index > 0.9”, “abbreviated injury scale ≥ 4”, “hypothermia < 35°” and “ICU length of stay > 24 h” displayed a lower rate of full agreement, lower than in the upper-middle-income countries and in the same range as the lower-middle-income countries. “Pleural decompression”, “transfusion”, “tourniquet use” and “radiological therapeutic intervention” received less full agreement in the upper-middle-, lower-middle- and low-income countries as compared to high-income countries. In general, the rate of full agreement was lowest in the lower-middle-income countries with the exception of “catecholamine administration” and “transfusion” and the low-income countries. It is of note that all three participants of low-income countries fully agreed on all of the criteria of abnormal vital signs (cerebral, respiratory, cardiocirculatory, hypothermia).

The rate of disagreement (Fig. 2) was below 10% independent of the countries’ income level with a few exceptions: “death within 24 h” (12%) and “ICU length of stay > 24 h” (13%) in high-income countries and “death within 24 h” (16%) in lower-middle-income countries.

For seven criteria, one or two (out of three) participants of the low-income countries disagreed. In the upper-middle-income countries, the rate of disagreement was 10% or lower with all criteria.

Discussion

There was a high rate of full agreement with the suggested criteria to be used for the post hoc definition of the requirement for trauma team activation of at least 75% with 12 of the proposed criteria. These included “Glasgow coma scale < 9”, “respiratory rate < 9 or > 29/min”, “pericardiocentesis”, “advanced airway management”, “pulse oximetry (SpO2) < 90%”, “emergency surgery”, “systolic blood pressure < 90 mmHg”, “shock index > 0.9”, “cardiopulmonary resuscitation”, “deterioration of GCS ≥ 2 points before admission”,” chest tube or needle decompression” and “catecholamine administration”. They comprised nearly all of the criteria of abnormal vital signs and most of the criteria of life-saving interventions. This level of agreement was similar to the threshold of agreement of 75% and 80%, respectively, that had to be achieved in two different consensus statements for a criterion to be included [15, 17]

Looking at the level of full agreement, however, revealed some potential differences in the evaluation of some of the criteria with respect to a country’s income level. Interestingly, some of the criteria reached a lower level of full agreement in the high-income countries than in the upper-middle-income counties. The level of full agreement tended to be lower in the lower-middle- as compared to the upper-middle-income countries. The number of participants in the low-income countries was low so that the results could be highly variable. The rate of full agreement for criteria of abnormal vital signs (cerebral, respiratory, cardio-circulatory, hypothermia) as well as of advanced airway management tended to highest in the low-, upper-middle- and high-income countries in contrast to the lower-middle-income countries.

On the other hand, the level of disagreement was rather low, mostly expressed by single participants. The highest rate of disagreement (> 5%) was observed for “death within 24 h”. This leaves a number of the proposed criteria with partial agreement, i.e. a level of less than 75% of full agreement but less than 5% disagreement (“hypothermia < 35°”, “ > 2 external fixators (humerus, femur, pelvis), “abbreviated injury scale (AIS) ≥ 4”, “ICU length of stay > 24 h”, “transfusion”, “tourniquet (pre-hospital)” and “radiological therapeutic intervention”.

Although the general full agreement for the proposed criteria of post hoc trauma team requirement is very high irrespective of the country’s income level, some of the criteria may deserve some more discussion before they may reach a higher level of agreement (or are being rejected). There is no uniform pattern of different levels of agreement in the order of a country’s income. There is less full agreement for some of the criteria in high- versus upper-middle-income countries.

The survey was like a single-point vote without the possibility of discussing the different items with the other participants. Therefore, partial agreements might be “upgraded” to full agreement (or disagreed) after the exchange of arguments and rationales. This would be the normal process of achieving consensus. In the cited consensus statements, up to five voting rounds were required to achieve agreement [15, 17]. Having this in mind, the agreement within this single survey voting appears high and it may be concluded that the proposed criteria may be useful for most countries independent of their level of income. Nevertheless, more discussions on an international level appear to be warranted to achieve a full consensus to define a universal set of criteria that will allow for quality assessment of over- and undertriage of trauma team activation for the most severely injured patients worldwide.

The major limitation of the study is the selection bias introduced by selecting the participants based on personal knowledge and recommendation. The participants were contacted based on the recommendation of 12 different members of the study group. They may lack the possible variability of opinions compared to a random sample. Therefore, the selection of participants appears arbitrary and not representative. For example, there is a preponderance of tertiary care hospitals and the low number of hospitals included from low-income countries may bias interpretation of this proportion of the study cohort. On the other hand, our participants represent different disciplines involved in trauma care such as trauma surgeons (general surgeons), trauma surgeons (orthopedic surgeons), anesthesiologists or emergency physicians thus representing a variety of different backgrounds. Also, a high rate of responders and the personal acquaintance may offer the chance to receive valid and thoughtful answers, particularly concerning the answers about the trauma team requirement, where some thorough thought on the side of the participants is essential. Other types of selection may introduce other biases. The variation of using an “official” mailing list from worldwide active organizations would have resulted in a more representative list of countries. However, it remains arbitrary who of the physicians contacted would actually answer, which may reduce the representativeness. The less personal character of the contact with the potential participant may also confound the thoughtfulness of some of the answers. Our return rate of 75.5% compares favorably to the return rate of a study using mailing lists from international societies and networks (54%) [21]. Including participants from one medical society (e.g. only surgeons) may also bias the results. In both approaches, it is not clear whether the answers would be representative for a whole country or would be more specific to the institution and the setting of the respondent. That this may be the case was shown by the quite differing answers from participants originating in the same country. Bearing this in mind, our results have to be interpreted with caution.

However, many of the answers received in the survey of Miclau et al. [21] and our study are quite comparable: There was a similar availability of designated trauma centers (33.3 vs. 27.8% in low-income countries and 68.8 vs. 71.0% in high-income countries). The availability of a formalized emergency medical service is in the same range for all levels of income in both studies, indicating that the participating countries in our survey may not substantially differ from a larger cohort of countries. In a systematic review about trauma systems around the world 32 countries have been evaluated [22]. The authors included fewer low- and middle-income countries (N = 9) compared to 23 countries of that type in our study. Therefore, their results with respect to tertiary care trauma centers and the availability of a trauma team may not be comparable to ours. Furthermore, 84% of the publications used in their study were older than 5 years and 50% older than 10 years, so that considerable improvements may have taken place since then in many countries.

There was a preponderance of participants from tertiary care hospitals in all country income levels. Their experience and rating may be different from physicians working in regional or local hospitals. It might be speculated that such differences could be more pronounced in countries with a lower per capita income [21]. However, the assessment from our participants from regional or local trauma hospitals did not differ substantially from those from tertiary care hospitals, although the numbers are too small to rule out this possibility. To get a definite answer, it would require interviewing physicians from hospitals from all levels of trauma care in each country. Nevertheless, it appears reasonable to assume that the participants of our study did not answer in complete contradiction to the general rating within their respective country.

The number of participating countries in our survey amounted to around 20% of all countries within the same income level, with a clear underrepresentation of low-income countries. Therefore, the high level of agreement shown in our survey may not be true for low-income countries. Indeed, Miclau et al. [21] have shown, that even in designated trauma centers in low-income countries, important musculoskeletal injury resources such as spine board, pelvic binder, computed tomography or post-anesthesia care unit are lacking to a much higher degree in comparison with countries with lower-middle-income or higher-income level.

Although we have gathered information about pre-hospital trauma care and facility-based trauma care, we cannot assign to our participants the WHO trauma maturity index [23], because we are lacking information about education and training and quality assurance. We did not explicitly assess whether our participants in low- and middle-income countries fulfill the Bellwether procedures for essential surgical care like cesarean delivery, laparotomy and treatment of open fractures [24]. Since all of them do have a general surgeon (100%), a trauma or orthopedic surgeon (100%) and a gynecologist (69%) as well as a specially equipped resuscitation area available, they could be classified as fulfilling the requirements of a high-level care.

Despite these limitations, it appears valid to assume that the proposed criteria for correct trauma team activation may be useful not only for high-income countries but at least also for lower-middle- and upper-middle-income countries. Although the requirements they pose may not be met in low-income countries and the entire territory of middle-income countries they appear to be recognized by many of the physicians practicing in these countries as well as in the high-income countries. They could be used for quality assurance in the care of severely or polytraumatized patients within trauma hospitals with benchmarks individualized by countries and dynamic over time. While there appears to be a large subset of criteria with high universal acceptance, some of the criteria with only partial agreement or even disagreement will have to be discussed in the future on a worldwide or a country-specific level to recommend which patient should or should not have received trauma team activation. A generally accepted or locally adapted criterion standard could be used to validate field triage criteria as well as to measure the performance of trauma systems in the different countries and adapt them to their specific conditions, circumstances and resources. It could further be used to compare the efficiency and capabilities of the initial care of severely injured patients worldwide.

References

World Health Organisation. Injuries and violence: the facts 2014. 2014. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/149798/9789241508018_eng.pdf;jsessionid=4504670A98DD3B2EF1122AB0DC881851?sequence=1. Accessed 18 Sep 2018.

Lashoher A, Schneider EB, Juillard C, Stevens K, Colantuoni E, Berry WR, et al. Implementation of the World Health Organization Trauma Care Checklist Program in 11 Centers Across Multiple Economic Strata: Effect on Care Process Measures. World J Surg. 2017;41:954–62.

Sasser SM, Hunt RC, Faul M, Sugerman D, Pearson WS, Dulski T, et al. Guidelines for field triage of injured patients: recommendations of the National Expert Panel on Field Triage, 2011. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2012;61:1–20.

Davis JW, Dirks RC, Sue LP, Kaups KL. Attempting to validate the overtriage/undertriage matrix at a Level I trauma center. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017;83:1173–8.

Jensen KO, Heyard R, Schmitt D, Mica L, Ossendorf C, Simmen HP, et al. Which pre-hospital triage parameters indicate a need for immediate evaluation and treatment of severely injured patients in the resuscitation area? Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2019;45:91–8.

Rotondo M, Cribari C, Smith R, editors. Resources for optimal care of the injured patient. Chicago: American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma; 2014.

van Laarhoven JJ, Lansink KW, van Heijl M, Lichtveld RA, Leenen LP. Accuracy of the field triage protocol in selecting severely injured patients after high energy trauma. Injury. 2014;45:869–73.

Rehn M, Eken T, Kruger AJ, Steen PA, Skaga NO, Lossius HM. Precision of field triage in patients brought to a trauma centre after introducing trauma team activation guidelines. Scand JTrauma Resuscitat Emerg Med. 2009;17:1.

Uleberg O, Vinjevoll OP, Eriksson U, Aadahl P, Skogvoll E. Overtriage in trauma—what are the causes? Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2007;51:1178–83.

Kane G, Engelhardt R, Celentano J, Koenig W, Yamanaka J, McKinney P, et al. Empirical development and evaluation of prehospital trauma triage instruments. J Trauma. 1985;25:482–9.

West JG, Murdock MA, Baldwin LC, Whalen E. A method for evaluating field triage criteria. J Trauma. 1986;26:655–9.

Najafi Z, Abbaszadeh A, Zakeri H, Mirhaghi A. Determination of mis-triage in trauma patients: a systematic review. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2019;45:821–39.

Bardes JM, Benjamin E, Schellenberg M, Inaba K, Demetriades D. Old age with a traumatic mechanism of injury should be a trauma team activation criterion. J Emerg Med. 2019;57:151–5.

Bieler D, Trentzsch H, Baacke M, Becker L, Dusing H, Heindl B, et al. Optimization of criteria for activation of trauma teams: avoidance of overtriage and undertriage. Unfallchirurg. 2018;121:788–93.

Lerner EB, Drendel AL, Falcone RA Jr, Weitze KC, Badawy MK, Cooper A, et al. A consensus-based criterion standard definition for pediatric patients who needed the highest-level trauma team activation. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;78:634–8.

Willenbring BD, Lerner EB, Brasel K, Cushman JT, Guse CE, Shah MN, et al. Evaluation of a consensus-based criterion standard definition of trauma center need for use in field triage research. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2016;20:1–5.

Waydhas C, Baake M, Becker L, Buck B, Düsing H, Heindl B, et al. A consensus-based criterion standard for the requirement of a trauma team. World J Surg. 2018;42:2800–9.

Civil I. Which end of the telescope brings trauma triage into true focus? World J Surg. 2018;42:2813–4.

Stewart BT. Commentary on 'A Consensus-Based Criterion Standard for the Requirement of a Trauma Team:' low-resource setting considerations. World J Surg. 2018;42:2810–2.

The World Bank. World Bank Country and Lending Groups. 2017. https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519. Accessed 18 Sep 2018.

Miclau T, Hoogervorst P, Shearer DW, El Naga AN, Working ZM, Martin C, et al. Current status of musculoskeletal trauma care systems worldwide. J Orthop Trauma. 2018;32(Suppl 7):S64–S70.

Dijkink S, Nederpelt CJ, Krijnen P, Velmahos GC, Schipper IB. Trauma systems around the world: a systematic overview. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017;83:917–25.

Organization WH. Trauma system maturity index. 2019. https://www.who.int/emergencycare/trauma/essential-care/maturity-index/en/. Accessed 15 Apr 2019

O’Neill KM, Greenberg SL, Cherian M, Gillies RD, Daniels KM, Roy N, et al. Bellwether procedures for monitoring and planning essential surgical care in low- and middle-income countries: caesarean delivery, laparotomy, and treatment of open fractures. World J Surg. 2016;40:2611–9.

Acknowledgements

Open Access funding provided by Projekt DEAL. The WORLD-Trauma TAcTIC Study Group: Khaled Tolba Younes Abdelmotaleb, MD. Department of Anesthesia and Intensive Care, Faculty of Medicine, Aswan University, Aswan 81528, Egypt; George Abi Saad, MD, Trauma Services and Surgical Critical Care, American University of Beirut, Riad El-Solh 1107 2020, PO Box 11–0236, Beirut, Lebanon; Markus Baacke, Krankenhaus der Barmherzigen Brüder, Nordallee 1, 54292 Trier, Germany; Nehat Baftiu MD, PhD, University Clinical Centre of Kosovo, QKUK, 10000 Pristine, Republic of Kosovo; Christos Bartsokas, MD, PhD, Hippokration General Hospital of Athens, Vas.Sofias 114 ave. Region of Attica, Athens, 11527, South Africa; Lars Becker, Dr., University Hospital Essen, Hufelandstraße 55, 45147 Essen, Germany; Marco Luigi Maria Berlusconi, Dr., Responsabile di Unità Operativa Traumatologia II, Istituto Clinico Humanitas, Via Alessandro Manzoni, 56, 20089 Rozzano MI, Italy; Artem Bespalenko, Dr., Traumatology Department, Military Medical Clinical Centre of Occupational Pathology of Personnel, Odynadtsyata Linia 1, 08200 Irpin, Ukraine; Dan Bieler, Dr., Bundeswehrkrankenhaus, Rübenacher Straße 170, 56072 Koblenz, Germany; Martin Brand, MD, Department of Surgery, University of Pretoria, Bridge E, Level 7; Surgery, Steve Biko Academic Hospital, Cnr Steve Biko Road & Malan Street; Prinshof, 349-Jr, Pretoria 0002, South Africa; Edilson Carvalho de Sousa Júnior, Dr., Departamento de Clínica Geral—Cirurgia II, Universidade Federal do Piauí, Hospital São Marco, R. Olávo Bilac, 2300, Teresina, Brazil; Narain Chotirosniramit, Prof. Dr. Bangkok Hospital Chiang Mai, Mueang Chiang Mai, Thailand; Yuhsuan Chung, MD, Show Chwan Memorial Hospital, No. 542, Sec 1, Zhongshan Rd., 50008 Changhua Changhua City, Taiwan; Lesley Crichton, Dr., Department of Anaesthesia, University Teaching Hospital, Lusaka, Private Bag RW1X Ridgeway, Nationalist Road, Zambia; Peter De Paepe, MD, PhD, Department of Emergency Medicine, Ghent University Hospital, C. Heymanslaan 10, 9000 Ghent, Belgium; Agron Dogjani, MD, PhD, University Hospital of Trauma, Str. Lord Bajron No 40, PC 1026, Tirana, Albania; Dietrich Doll, MD, PhD, Sankt Marienhospital, Marienstr. 6–8, D-49377 Vechta, Germany and Department of Surgery, School of Clinical Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Jubilee Road Parktown, Johannesburg, 2196, South Africa; Ayene Gebremicheal Molla, Aksum University College of Health Science and Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Aksum City, Tigray, Ethiopia; Timothy C. Hardcastle, MMed, FCS(SA), PhD, Inkosi Albert Luthuli Central Hospital, 800 Vusi Mzimela Rd, 4058 Mayville and University of Kwa Zulu Natal, Congella, South Africa; Kastriot Haxhirexha, Dr., MD, PhD—Clinical Hospital Tetove, 29 Noemvri NN, 4200 Tetove, Republic of the North Macedonia; Kajal Jain, MD, Department of Anesthesia & Intensive Care, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India; Kai Oliver Jensen, Dr., Klinik für Traumatologie, UniversitätsSpital Zürich, Rämistrasse 100, 8091 Zürich, Switzerland; Andrey Korolev, Dr., European Clinic of Sports Traumatology and Orthopaedics, Orlovsky pereulok 7, Moscow, Russia, 129110; Li Zhanfei, Dr., Tongji Trauma Center, Tongji Hospital, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, 1095 Jie Fang Da Dao, 430030 Wuhan, Hubei Province, P.R. China; Jerry K. T. Lim, Dr., Department of Anaesthesia and Surgical Intensive Care, Changi General Hospital, 2 Simei Street 3, Singapore 529889, Singapore; Fredrik Linder, Prof. Dr., Department of Surgical Sciences, Section of Radiology, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden; Nurhayati Lubis, MBBS, Bartshealth NHS Trust, Whipps Cross Hospital, London E11 1NR, Great Britain; Nina Magnitskaya, Dr., European Clinic of Sports Traumatology and Orthopaedics, Orlovsky pereulok 7, Moscow, Russia, 129110; Damian MacDonald, MD FRCPC FACEP EBCEM, Assistant Professor, Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Ottawa, Canada; Martin Mauser, MD Dr., Chris Hani Baragwanath Academic Hospital, Soweto, Johannesburg, South Africa; Gerrit Matthes, Dr., Klinikum Ernst von Bergmann, Charlottenstr. 72, 14467, Potsdam, Germany and Committee on Emergency Medicine, Intensive Care and Trauma Management (Sektion NIS) of the German Trauma Society; Kimani Mbugua, MD, Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital, Nandi road, 30100 Eldoret, Kenya; Sergey Mlyavykh, Dr., Trauma and Orthopedics Institute, Privolzhsky Research Medical University, 18, Verhne-Voljskaya naberejnaya, Nizhniy Novgorod, Russia, 603155; Barbaro Monzon, Dr. MD, Head Clinical Department of General Surgery, Pietersburg Hospital Polokwane 0700, South Africa, Department of Surgery, School of Medicine; Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Limpopo, South Africa; Munkhsaikhan Togtmol, Prof. Dr., General Director of National trauma and Orthopedic Research Center of Mongolia, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia; Khreshi Mustafa, Dr. Al-Zakat Hospital, Tulkarm, Palestine; Michael Mwandri, MD PhD, University of Kwazulu Natal, South Africa, Trauma system research Adjunct physician, Meru district government hospital, P O Box 135, Duluti, Arusha, Tanzania; Pradeep Navsaria, MD, Trauma Center, Groote Schuur Hospital, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town, Private Bag X4, Main Road, Observatory 7937, South Africa; Stefan Nijs, Prof. Dr., Medical Head of the Traumatology Department, University Hospital Leuven, Belgium; Francisco Olmedo, Dr., HELIOS Klinikum Pforzheim, Abteilung für Unfallchirurgie und Orthopädie, Kanzlerstr. 5–7, 75175 Pforzheim, Germany; Maria C. Ortega Gonzalez, Dr., Specialist Anaesthesiologist, Director of Trauma Anaesthesia Netcare Milpark Hospital, South Africa; Jesús Palacios Fantilli, Dr, Médico de Planta Hospital de Trauma, Avenida General Santos esquina Teodoro Mongelos, Asunción, Paraguay; Marinis Pirpiris, MD, Active Orthopaedic Centre, Epworth Hospital, Epworth Centre, Level 7 Suite 5 32 Erin Street, Richmond, Victoria 3121, Australia; Francois Pitance, Dr., Traumacenter Coordinator, CHR Liège, Boulevard XII eme de ligne, 4000 Liège, Belgium; Eoghan Pomeroy, Dr., Department of Trauma and Orthopaedics, University Hospital Waterford, Dunmore Road, County Waterford, Ireland.; M. A. Sadakah, MD, Orthopedic Surgery and Traumatology, Tanta University Hospital, Egypt,Present address: Langbürgnerstraße 7c, 81549 München, Germany; Tapas Kumar Sahoo, MD, Institute of Critical Care, Medanta Abdur Razzaque Ansari Memorial Weaver's Hospital, Ranchi, India; Iurie Saratila, MPH, University Center for Simulation in Medical Training, Nicolae Testemitanu State University of Medicine and Pharmacy of the Republic of Moldova, bd. Stefan cel Mare si Sfant 165, Chisinau, Moldava; Sandro Scarpelini, Dr., Faculdade de Medicina de Ribeirão Preto da Universidade de Sao Paulo, Rua Bernardino de Campos 1000, Higienopolis 14015130, Ribeirão Preto, Brazil; Uwe Schweigkofler, Dr., BG Unfallklinik Frankfurt am Main gGmbH, Friedberger Landstraße 430, 60389 Frankfurt, Germany; Edvin Selmani, MD., Orthopedic and Trauma, University Trauma Hospital, Qyteti i nxenesve, pranë Birra Tirana, Kutia postare 8174, Tirana, Albania; Tim Søderlund, Dr., Trauma unit, Töölö Hospital, Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, Helsinki University Hospital, Topeliuksenkatu 5, P.O.Box 266, FI-00029, Helsinki, Finland; Michael Stein MD, FACS, Director of Trauma, Department of Surgery, Rabin Medical Center—Beilinson Hospital, Petach-Tikva, 49100, Israel; Buland Thapa, MD, Nepal Orthopedic Association, Siddhi Charan Road 260/19 Swoyambhu- 15, Kathmandu, Nepal; Heiko Trentzsch, Dr., Institut für Notfallmedizin und Medizinmanagement (INM), Klinikum der Universität München, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, Schillerstr. 53, 80336 München, Germany and Committee on Emergency Medicine, Intensive Care and Trauma Management (Sektion NIS) of the German Trauma Society; Teodora Sorana Truta, MD, Emergency Department, Mures Emergency County Hospital, Gheorghe Marinescu street 50, 540136 Targu-Mures, Romania; Selman Uranues, MD Dr., Department of Surgery, Medical University of Graz, Auenbruggerplatz 29, 8036 Graz, Austria; Christian Waydhas, Dr., Berufsgenossenschaftliches Universitätsklinikum Bergmannsheil, Bürkle-de-la-Camp-Platz 1, 44789 Bochum, Germany and Medical Faculty of the University Duisburg-Essen, University Hospital, Hufelandstr. 55, 45147 Essen, Germany; Christoph G. Wölfl, Dr., Marienhausklinikum Hetzelstift Neustadt an der Weinstraße, Stiftstraße 10, 67434 Neustadt/Weinstraße, Germany; Sandar Thein Yi, MD, Department of Anaesthesia, University of Medicine, 30th Street, Between 73rd and 774th Streets Chanayetharsan Township, Mandalay, Myanmar.; Ihor Yovenko, MD, Intensive Care Unit, Medical House Odrex, Raskidaylovskaya St., Odessa 65110, Ukraine; Pablo Zapattini, Dr., Mariano Roque Alonso, Asuncion, Paraguay

Funding

There was no funding involved in the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

CW: Conception and designing the study, acquisition of participants, designing the survey questions, conducting the study (acquisition, analysis, or interpretation), drafting the manuscript. HT: Conception and designing the study, designing the survey questions, acquisition of participants, critically revising the manuscript. TCH: Designing the survey questions, supplying data, drafting the manuscript, critically revising the manuscript. KOJ: Conception and designing the study, acquisition of participants, designing the survey questions, supplying data, critically revising the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

There were no financial and personal relationships with other people or organizations to disclose by any of the authors.

Additional information

The members of the World-Trauma TAcTIC Study Group mentioned in Acknowledgements section.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Waydhas, C., Trentzsch, H., Hardcastle, T.C. et al. Survey on worldwide trauma team activation requirement. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 47, 1569–1580 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-020-01334-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-020-01334-z