Abstract

Stacking interactions play an important role in stabilizing DNA and RNA secondary structure. To select a computational level to study the stacking interactions, both energy and geometric criteria, as well as the time necessary to optimize the system, should be taken into account. In this work, an attempt was made to find the most optimal level of theory describing the stacking interactions in adenine dimers. The obtained results have shown that for this purpose, wB97XD/6-311G(p,d), wB97XD/aug-cc-pvdz, or B97D3/aug-cc-pvdz should be used. What is more, geometry of the most preferable arrangements of molecules was also pointed out, ensuring an optimal starting system for further analyses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

It is a trivial statement to say that DNA and RNA biopolymers are of fundamental importance for life. Ever since the Pauling [1] and Crick and Watson [2] discoveries, topology of covalently linked nucleic bases, via the connections by ribosome and phosphate anion, has been recognized as a leading concept to the helix. Next, the H-bond interactions were acknowledged for a certain stiffness of the helix-like strands. H-bonding is a well-recognized type of interaction [3,4,5,6] and—in principle—does not present any particular problem in computational descriptions of the interactions between pairs and other complexes of nucleic acids [7]. Much more complex is another very important interaction, although rather weak, known as the stacking. It takes place—in general—as an interaction between π-electron structures of two planar or close to planar molecules, often parallel one against another and having a rich π-electron population. There are many conformations of stacking pairs of nucleic bases [8], and hence any computational approach is a complex problem [9, 10]. There are many detailed works in this field of research (for reviews, see [11,12,13,14]). It should be emphasized that the evaluation of stacking interaction requires the use of accurate quantum-chemical methods, for example, MP2 or CCSD(T) [15, 16]. However, their use is limited to a rather small system (e.g., benzene dimer) [17]. In the case of larger systems, these calculations are considerably time and resource consuming [16]. For this reason, often, interactions are studied at higher computational level (e.g., MP2) for geometry optimized at DFT level [18, 19].

Summarizing, noncovalent interactions govern the structure and conformational dynamics of molecular systems, and hence they are crucial for their chemical properties. Therefore, the ability to understand and predict noncovalent interactions is very important. Computational studies are necessary for these purposes. Due to the size of the studied systems, it is very important to choose the appropriate level of calculation (methods and basis sets). Our research focuses on assessing the impact of a substitution on the structure and energy of stacking interactions of adenine dimers. Thus, the aim of this paper is to present the most effective computational approach which can reliably describe the abovementioned interactions. For this purpose, adenine dimers presenting a variety of mutual orientation of molecules, as well as variants of methods/basis sets, were selected.

Methodology

Choice of input structures

Adenine may participate in various stacking interactions that differ in the mutual orientation of molecules, a distance between them, a tilt, and a shift of individual adenine molecule. In order to determine an optimal method and basis set to describe such interactions, a set of most representative systems needs to be selected. Adenine can participate in amino-imino types of tautomeric equilibria leading to 12 possible tautomers [20]. A molecule of adenine can adopt four (stable) “amino” tautomers, from which the most stable and most occurring one in biological systems is conformer 9H [21]. Thus, this tautomer is the most often described. The Hobza group analyzed optimal arrangements of 9H adenine dimers using single-point calculations [22]. From this work, we have selected eight systems in their geometry corresponding to the minimum on the potential energy curve (A–H) and used them as input structures for systems modeling the most common adenine behavior (Fig. 1, for input data set, see S.I.).

Choice of methods and basis sets

Intermolecular stacking interactions, due to their nature, need to be described using diffusion corrections. Additionally, in a selection of level of theory, calculation speed and low computational cost play important roles. Therefore, DFT-D methods were used and, according to the suggestions from the Hobza group [11], the following functionals were chosen: B97D [14], B97D3 [23], wB97XD [24], M06-2X [25], and additionallyCAM-B3LYP [26]. Since the basis set selection may also play the important role in the resulting geometry and energy, geometry optimization computations were carried out in various basis sets: Pople’s [27] 6-311++G(d,p); Dunning’s [28] aug-cc-pvdz, aug-cc-pvtz, and daug-cc-pvdz; and Ahlrichs’ [29, 30] (def2tzvpp). The latter basis set gives results that DFT calculations can be regarded as close to the complete basis set limit, whereas cam-b3lyp/def2tzvpp calculations resulted in one of the best performance for optimizing molecular geometries [31]. All calculations with full geometry optimizations were performed using Gaussian 09 [32].

Results and discussion

The research focused on the selection of the most optimal computational level to study stacking interactions in 9H adenine dimers. To evaluate the final results, the energy criteria were taken into consideration. However, due to possible geometry changes during optimization, special attention was also paid to deviation between input and output structures. Additionally, since the carried calculations were devoted to a simple model system, underlying further modification in the future work, ease of converging was also an important factor for final selection of the optimum method/basis set. What is more, the selection of a relatively stable system and energy of stacking interactions within was also of our interest.

Assessment of energy values of interactions in output geometries

Interaction energy (Eint) between two fragments of A···B system was calculated according to Eq. (1):

where EA(basisA···B; optA···B) and EB(basisA···B; optA···B) are the energies of the A and B molecules, respectively, for its geometries obtained during the optimization of the A···B system and calculated using internal coordinates of the A and B molecules; basisA···B; EA···B(basisA···B; optA···B) means the energy of the optimal A···B complex.

So, all of the interaction energies have been corrected for the basis set superposition error (BSSE) using the counterpoise technique [33, 34]. BSSE is determined by the equation:

The total energy of interaction (Etot), also known as binding energy, is a sum of the interaction energy, Eq. (1), and deformation (Edef). The latter is the amount of energy-characterizing changes in geometries of A and B from the optimized ones to their geometry in the complex (A···B), and therefore is always positive. The deformation energy can be calculated as:

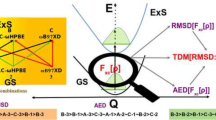

The obtained values of interaction energies are presented in Table 1 and Fig. 2, while BSSE values are also shown in Fig. S1 (Supplementary Information). In addition, energy values for the obtained optimal geometries of the studied systems and deformation energies are gathered in Tables S1and S2, respectively.

Although the values of the interaction energy differ depending on the used level of theory, the trends remain similar, except for the results obtained for CAM-B3LYP/def2tvzpp optimizations (presented below in a separate subsection). It appears that stacking interactions between parallel adenine molecules (system A) are weak and its mean value is − 2.44 ± 1.04 kcal mol−1. Moreover, in the case of this system as well as for B and C ones, the weakest interactions were predicted by the M06-2X functional. Interactions in geometries D, E, and G are described by similar energy values (− 8.73 ± 0.64, − 8.98 ± 0.50, and − 9.03 ± 0.56 kcal mol−1, respectively, without including CAM-B3LYP/def2tvzpp results), and what is not surprising is that after the optimization, the mutual orientation of adenine molecules in those systems is averaged (Fig. 3). The strongest stacking interactions were found for F system (Eint from − 9.41 up to − 11.36 kcal mol−1, see Table 1 and S1), and the largest geometry changes were also found in this case (see below).

BSSE values seem to be almost constant for each method/basis set used, and thus system A seems to be an exception, since obtained BSSE values for this geometry are lower in comparison to those of any other system (Fig. S1 in SI). The smallest BSSE values (ca. 0.5 kcal mol−1) are found in the case of the largest basis sets, i.e., the triple ζ type (aug-cc-pvtz and def2tzvpp), as expected. Furthermore, in most cases, BSSE values are greater than the calculated deformation energies (Table S2 in SI).

Assessment of output geometries

Bearing in mind the importance of changes in the geometry of the optimized systems, quantitative parameter, namely RMS (root mean square) indicating average distance between heavy atoms in systems before and after calculations, was introduced to the study. Table 2 contains obtained values of RMS parameter.

As mentioned above, the input geometries of studied systems were “artificial,” not optimized ones, and thus they should be treated only as reference, not as a goal configuration.

Systems A, D, E, and G were successfully optimized without significant geometry changes in all used methods and basis sets, apart from CAM-B3LYP/def2tzvpp (Figs. 3 and 4). In the case of the first two, optimized conformations showed higher raise [35], when compared to input geometries. A raise and a discrete shift [35] of adenine molecule was observed in the case of E and G systems. In both cases, changes lead to the final conformation close to D system. B and H were found to be the most unstable input configurations, what resulted in difficulties in converging as well as inconsistent optimal geometry throughout the applied level of theory (Fig. 4). Geometry changes in the system F lead unanimously to the tilt and the twist of adenine molecule (depicted in Fig. 4). Additionally, these geometry changes can be connected to the strongest stacking interactions (the highest absolute value of the stacking energy, Eint, see Fig. 2 and Table 1).

Optimization results with CAM-B3LYP/def2tzvpp

The most extreme geometry changes were observed using the CAM-B3LYP method. Although input structures consisted the systems exhibiting π···π interactions, in 4 out of 8 examples (systems A,B, C, F, and H), adenine molecules were shifted to be co-planar and further stabilized by hydrogen bonds. What is worth noticing, in structures B, C, F, and H, hydrogen bonds have been formed spontaneously (Fig. 5, Table 3). In the case of system A, molecules have shifted, destroying stacking interactions and trying to form H-bonds, yet optimal geometry has not been reached.

Centrosymmetric, hydrogen bond–stabilized dimers formed in systems C and H are also present in adenine crystal structure deposited in the crystallographic database CSD [36]. Experimental D···A distance lengths are significantly shorter; however, overall geometry is reasonably well predicted. The resulting dimers of B and F are not found in any crystal structures of adenine, probably due to their less preferable, asymmetric character, yet their geometry remains realizable. Estimated energy values of hydrogen bonds formed in the case of B and C systems are close to average stacking interaction energy for E and F systems obtained by different methods/basis sets, respectively. It can be concluded that although CAM-B3LYP/def2tvzpp level of theory provides well simulation of H-bond geometry, the energy of those interactions remains underestimated.

In the case of D, E, and G systems, stacking interactions are preserved, yet interaction energies were heavily underestimated. Thus, both energy and RMS values for optimization results visibly deviate from the ones obtained with a different level of theory. In Fig. 4, in yellow color, CAM-B3LYP/def2tvzpp output geometry was distinguished. It can be concluded that the overestimated distance between adenine molecules resulted in an understatement of energy of stacking interactions.

Conclusions

The clue of conducted research was to determine which method/basis set would be appropriate to analyze stacking interactions between adenine molecules, simulating aggregates present in secondary structure of DNA and RNA nucleic acids. In the course of the research, system A (presenting parallel orientation of adenine monomers) and system D (contained molecules twisted by 180°) appeared to be the easiest to converge and thus the most stable from this point of view. Twisted F geometry was exhibiting the strongest stacking interactions, i.e., the interaction energy equaled about − 10.7 kcal mol−1, meanwhile energy of A and D systems was determined as ca. − 2.4 kcal mol−1 and − 8.7 kcal mol−1, respectively.

Disproportionally long walltime was necessary to finalize optimization in the case of use aug-cc-pvtz and daug-cc-pvdz basis sets, and thus despite more accurate energy estimation for some systems, complete data in those cases was not obtained.

Taking into consideration the comparison of energy values for each system between all applied methods/data sets and the ease of converging, three of the most optimal methods/basis sets have been chosen to be the best in describing stacking interactions, namely wB97XD/6-311G(p,d), wB97XD/aug-cc-pvdz, and B97D3/aug-cc-pvdz.

Calculations performed with CAM-B3LYP/def2tvzpp in some cases unexpectedly resulted in formation of hydrogen bonds between adenine molecules. Although in the literature this method/basis set variant was successfully used to describe geometry and π-electron delocalization of hetero- and polycyclic molecules [31, 37], it is not appropriate in the case of stacking interactions in adenine dimers.

References

Pauling L, Corey RB (1953) A proposed structure for the nucleic acids. Proc Natl Acad Sci 39:84–97. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.39.2.84

Watson JD, Crick FHC (1953) Molecular structure of nucleic acids: a structure for deoxyribose nucleic acid. Nature 171:737–738. https://doi.org/10.1038/171737a0

Jeffrey GA, Saenger W (1991) Hydrogen bonding in biological structures. Springer-Verlag, Berlin Heidelberg

Jeffrey GA (1997) An introduction to hydrogen bonding. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Scheiner S (1997) Hydrogen bonding: a theoretical perspective. Oxford University Press on Demand, Oxford

Grabowski SJ (ed) (2006) Hydrogen bonding: new insights. Springer, Dordrecht

Hobza P, Šponer J (1999) Structure, energetics, and dynamics of the nucleic acid base pairs: nonempirical ab initio calculations. Chem Rev 99:3247–3276. https://doi.org/10.1021/cr9800255

Šponer J, Leszczyński J, Hobza P (1996) Nature of nucleic acid−base stacking: nonempirical ab initio and empirical potential characterization of 10 stacked base dimers. Comparison of stacked and H-bonded base pairs. J Phys Chem 100:5590–5596. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp953306e

Elstner M, Hobza P, Frauenheim T, Suhai S, Kaxiras E (2001) Hydrogen bonding and stacking interactions of nucleic acid base pairs: a density-functional-theory based treatment. J Chem Phys 114:5149–5155. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1329889

Poater J, Swart M, Bickelhaupt FM, Fonseca Guerra C (2014) B-DNA structure and stability: the role of hydrogen bonding, π–π stacking interactions, twist-angle, and solvation. Org Biomol Chem 12:4691–4700. https://doi.org/10.1039/C4OB00427B

Riley KE, Pitoňák M, Jurečka P, Hobza P (2010) Stabilization and structure calculations for noncovalent interactions in extended molecular systems based on wave function and density functional theories. Chem Rev 110:5023–5063. https://doi.org/10.1021/cr1000173

Riley KE, Hobza P (2011) Noncovalent interactions in biochemistry: noncovalent interactions in biochemistry. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Comput Mol Sci 1:3–17. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcms.8

Hobza P (2012) Calculations on noncovalent interactions and databases of benchmark interaction energies. Acc Chem Res 45:663–672. https://doi.org/10.1021/ar200255p

Christensen AS, Kubař T, Cui Q, Elstner M (2016) Semiempirical quantum mechanical methods for noncovalent interactions for chemical and biochemical applications. Chem Rev 116:5301–5337. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00584

Jurečka P, Šponer J, Černý J, Hobza P (2006) Benchmark database of accurate (MP2 and CCSD(T) complete basis set limit) interaction energies of small model complexes, DNA base pairs, and amino acid pairs. Phys Chem Chem Phys 8:1985–1993. https://doi.org/10.1039/B600027D

Řezáč J, Riley KE, Hobza P (2011) S66: a well-balanced database of benchmark interaction energies relevant to biomolecular structures. J Chem Theory Comput 7:2427–2438. https://doi.org/10.1021/ct2002946

Zhikol OA, Shishkin OV, Lyssenko KA, Leszczynski J (2005) Electron density distribution in stacked benzene dimers: a new approach towards the estimation of stacking interaction energies. J Chem Phys 122:144104. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1877092

Shishkin OV, Elstner M, Frauenheim T, Suhai S (2003) Structure of stacked dimers of N-methylated Watson–Crick adenine–thymine base pairs. Int J Mol Sci 4:537–547. https://doi.org/10.3390/i4100537

Gu J, Wang J, Leszczynski J (2011) Stacking and H-bonding patterns of dGpdC and dGpdCpdG: performance of the M05-2X and M06-2X Minnesota density functionals for the single strand DNA. Chem Phys Lett 512:108–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cplett.2011.06.085

Hanus M, Kabeláč M, Rejnek J, Ryjáček F, Hobza P (2004) Correlated ab initio study of nucleic acid bases and their tautomers in the gas phase, in a microhydrated environment, and in aqueous solution. Part 3. Adenine. J Phys Chem B 108:2087–2097. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp036090m

Stasyuk OA, Szatyłowicz H, Krygowski TM (2014) Effect of H-bonding and complexation with metal ions on the π-electron structure of adenine tautomers. Org Biomol Chem 12:456–466. https://doi.org/10.1039/C3OB41653D

Morgado CA, Jurečka P, Svozil D, Hobza P, Šponer J (2010) Reference MP2/CBS and CCSD(T) quantum-chemical calculations on stacked adenine dimers. Comparison with DFT-D, MP2.5, SCS(MI)-MP2, M06-2X, CBS(SCS-D) and force field descriptions. Phys Chem Chem Phys 12:3522–3534. https://doi.org/10.1039/b924461a

Grimme S, Ehrlich S, Goerigk L (2011) Effect of the damping function in dispersion corrected density functional theory. J Comput Chem 32:1456–1465. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcc.21759

Chai J-D, Head-Gordon M (2008) Long-range corrected hybrid density functionals with damped atom–atom dispersion corrections. Phys Chem Chem Phys 10:6615–6620. https://doi.org/10.1039/b810189b

Zhao Y, Truhlar DG (2008) The M06 suite of density functionals for main group thermochemistry, thermochemical kinetics, noncovalent interactions, excited states, and transition elements: two new functionals and systematic testing of four M06-class functionals and 12 other functionals. Theor Chem Accounts 120:215–241. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00214-007-0310-x

Yanai T, Tew DP, Handy NC (2004) A new hybrid exchange–correlation functional using the Coulomb-attenuating method (CAM-B3LYP). Chem Phys Lett 393:51–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cplett.2004.06.011

Krishnan R, Binkley JS, Seeger R, Pople JA (1980) Self-consistent molecular orbital methods. XX. A basis set for correlated wave functions. J Chem Phys 72:650–654. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.438955

Dunning TH (1989) Gaussian basis sets for use in correlated molecular calculations. I. the atoms boron through neon and hydrogen. J Chem Phys 90:1007–1023. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.456153

Weigend F, Ahlrichs R (2005) Balanced basis sets of split valence, triple zeta valence and quadruple zeta valence quality for H to Rn: design and assessment of accuracy. Phys Chem Chem Phys 7:3297–3305. https://doi.org/10.1039/b508541a

Weigend F (2006) Accurate Coulomb-fitting basis sets for H to Rn. Phys Chem Chem Phys 8:1057–1065. https://doi.org/10.1039/b515623h

Andrzejak M, Kubisiak P, Zborowski KK (2013) Avoiding pitfalls of a theoretical approach: the harmonic oscillator measure of aromaticity index from quantum chemistry calculations. Struct Chem 24:1171–1184. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11224-012-0148-2

Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Scalmani G, Barone V, Mennucci B, Petersson GA, Nakatsuji H, Caricato M, Li X, Hratchian HP, Izmaylov AF, Bloino J, Zheng G, Sonnenberg JL, Hada M, Ehara M, Toyota K, Fukuda R, Hasegawa J, Ishida M, Nakajima T, Honda Y, Kitao O, Nakai H, Vreven T, Montgomery Jr JA, Peralta JE, Ogliaro F, Bearpark MJ, Heyd J, Brothers EN, Kudin KN, Staroverov VN, Kobayashi R, Normand J, Raghavachari K, Rendell AP, Burant JC, Iyengar SS, Tomasi J, Cossi M, Rega N, Millam NJ, Klene M, Knox JE, Cross JB, Bakken V, Adamo C, Jaramillo J, Gomperts R, Stratmann RE, Yazyev O, Austin AJ, Cammi R, Pomelli C, Ochterski JW, Martin RL, Morokuma K, Zakrzewski VG, Voth GA, Salvador P, Dannenberg JJ, Dapprich S, Daniels AD, Farkas Ö, Foresman JB, Ortiz JV, Cioslowski J, Fox DJ (2009) Gaussian. Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford, CT, USA, p 09

Boys SF, Bernardi F (1970) The calculation of small molecular interactions by the differences of separate total energies. Some procedures with reduced errors. Mol Phys 19:553–566. https://doi.org/10.1080/00268977000101561

Simon S, Duran M, Dannenberg JJ (1996) How does basis set superposition error change the potential surfaces for hydrogen-bonded dimers? J Chem Phys 105:11024–11031. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.472902

Czyżnikowska Ż (2009) On the importance of electrostatics in stabilization of stacked guanine–adenine complexes appearing in B-DNA crystals. J Mol Struct THEOCHEM 895:161–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.theochem.2008.10.040

Stolar T, Lukin S, Požar J, Rubčić M, Day GM, Biljan I, Jung DŠ, Horvat G, Užarević K, Meštrović E, Halasz I (2016) Solid-state chemistry and polymorphism of the nucleobase adenine. Cryst Growth Des 16:3262–3270. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.cgd.6b00243

Szczepanik DW, Solà M, Andrzejak M, Pawełek B, Dominikowska J, Kukułka M, Dyduch K, Krygowski TM, Szatylowicz H (2017) The role of the long-range exchange corrections in the description of electron delocalization in aromatic species. J Comput Chem 38:1640–1654. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcc.24805

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the Interdisciplinary Center for Mathematical and Computational Modeling (Warsaw, Poland) for providing computer time and facilities.

Funding

H.S. and T.M.K. thank the National Science Centre and Ministry of Science and Higher Education of Poland for supporting this work under the grant no. UMO-2016/23/B/ST4/00082. P.H.M. would like to acknowledge Operational Project Knowledge Education Development 2014-2020 co-financed by European Social Fund.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Marek, P.H., Szatylowicz, H. & Krygowski, T.M. Stacking of nucleic acid bases: optimization of the computational approach—the case of adenine dimers. Struct Chem 30, 351–359 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11224-018-1253-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11224-018-1253-7