Abstract

Early age deformations, in concrete, may lead to cracking reducing its mechanical properties and service live. Cracking risk analysis is an essential part of a concrete design, and coefficient of thermal expansion of concrete is indispensable for this purpose. In this paper, an approach that utilizes ultrasonic pulse velocity measurements for assessment of thermal expansion coefficient of concrete at the early age is proposed. An expression for the calculation of the coefficient of thermal expansion was derived based on the theory of poromechanics. Free shrinkage and ultrasonic pulse velocity of cement paste with water to cement ratio of 0.33 were measured starting from the casting, in order to validate the formula. The calculated values were in an agreement with the data found in the literature, though the effect of self-desiccation was not captured. In addition, the calculated value of thermal expansion coefficient was used for decoupling of autogenous and thermal shrinkage of cement paste. Decoupled linear autogenous shrinkage was compared to the autogenous shrinkage measured by volumetric method.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Thermal deformations have substantial impact on early-age cracking sensitivity of concrete, particularly in high-performance concrete (HPC), for which a high content of cementitious materials is inherent [20]. Hence, determination of coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE) of concrete is a vital part of cracking risk analysis.

Another important type of deformations in HPC in the analysis of crack sensitivity is autogenous shrinkage. It is agreed among most researchers and practitioners that autogenous shrinkage is the Achilles’ heel of HPC [19]. In recent years, considerable study has been given to autogenous shrinkage, in view of the increased interest to the HPC. Autogenous shrinkage is defined as isothermal macroscopic volume reduction during hydration of cementitious materials after the initial setting. Autogenous shrinkage does not include the volume change due to loss or ingress of substances, temperature variation, and application of external force or restraint.

Decoupling of thermal and autogenous shrinkage is a considerable challenge in cracking risk analysis. While drying during shrinkage measurements can be prevented easily, there is no way to entirely exclude thermal gradients in a concrete cross-section and changes of concrete temperature in time. In addition, in the proximity of setting time, CTE of cement paste varies drastically. Therefore, for the evaluation of thermal deformations, CTE of concrete cannot be considered a constant. Due to considerable variation of CTE at early ages separation of autogenous and thermal strains is an intricate problem. For this reason, it is an important research task to develop a method for the evaluation of CTE of cement paste and concrete.

Direct measurement of CTE is a difficult task. The use of buoyancy method for effective measurement of volumetric CTE is reported by several researchers [21, 22, 28, 29]. However, for this purpose, advanced instrumentation, such as high-precision temperature controlled bath, is required. The thermal gradient across a sample of cement paste, temperature dependence of buoyancy liquid, and the effect of temperature on the reaction of cement hydration are additional complicating factors. Finally, the results of buoyancy method for CTE measurements cannot be directly extended to concrete, because this method utilizes small specimens of paste or mortar sealed in a condom.

Thus, monitoring of early-age changes of CTE is a complicated procedure, associated with a variety of technical problems. A simplified approach to assess CTE is required. In the present paper, an approach to estimate CTE, using poromechanics theory and non-destructive testing, is suggested.

Modern poromechanics takes its origin from the pioneering works of Terzaghi on soil mechanics and the theory of poroelasticity of Biot. Poromechanics allows predicting the behavior of porous body based on the properties of the solid phase, pore fluid and porosity similarly to a homogenization approach used in composite materials, e.g. by Hashin [13]. An introduction to poromechanics may be found elsewhere, for example in the textbook by Coussy [4]. Recently, a number of researchers successfully applied poromechanics to cementitious materials [6, 7]. Here, a formula for coefficient of thermal expansion based on the theory of poroelasticity is derived. This formula utilizes basic measurements of elastic properties of a porous material that may be obtained by non-destructive testing, such as ultrasonic pulse velocity measurements. This approach is similar to the approaches of Scherer and Grasley that utilize poroelasticity to extract permeability of cement paste from thermal expansion and dynamic pressurization, respectively [11, 26].

To validate the formula, ultrasonic pulse velocity and free shrinkage of cement paste with water to cement ratio of 0.33 were measured starting from the casting. Based on ultrasonic pulse velocity measurements, a dynamic bulk modulus was calculated and coefficient of thermal expansion was evaluated and compared to the literature data. An agreement was found between the calculated values and the literature data, though the effect of self-desiccation was not captured. The calculated coefficient of thermal expansion was applied for decoupling of thermal and autogenous shrinkage of cement paste. Finally, decoupled linear autogenous shrinkage was compared to the measured volumetric autogenous shrinkage. This paper is an extended and enhanced version of the work originally reported in the conference CONCREEP 10 [32].

2 Theoretical background

In the current paper, a novel approach to the evaluation of the linear CTE is proposed. This approach relies on the theory of poroelasticity and utilizes the measurements of dynamic bulk modulus by means of ultrasonic pulse velocity. It is based on the assumption that the CTE and dynamic bulk modulus of cement paste are the undrained values. Poroelastic properties are considered undrained when a porous body is treated as a closed system made of the porous solid and the saturating fluid, which means the fluid is not allowed to escape from the pores [4].

When a saturated cement paste is heated, due to high CTE of water, pore pressure is created contributing to the thermal expansion of cement paste. This pore pressure is released slowly because of low permeability of cement paste [27]. Poromechanics approach can be used to measure permeability in saturated cement pastes [1, 26]. Indeed, the permeability of cement paste is very low (coefficient of permeability may be as low as 1 ÷ 10 × 10−16 m/s), so the temperature change in cement paste causes immediate thermal expansion with subsequent slow outflow of pore liquid. The temperature change of 40 °C in the cement paste sample of just 2.5 mm thickness may cause a continuous pore liquid flow enduring 2–8 h [1]. The velocity of ultrasound waves in cement paste is usually between 3500 and 4800 m/s [2], which is many orders of magnitude higher than permeability of cement paste. Thus, dynamic properties of cement paste, including immediate response to the change of temperature, i.e. CTE, should be considered undrained.

Let us recall some fundamental relationships from the poroelasticity [4, 8]. It should be noted that the following relationships are based on the assumptions of small strains and saturated isotropic linearly elastic porous body. In poromechanics, Biot’s coefficient (b) is one of the most important characteristics of a porous body. It represents the portion of the volumetric deformation produced by the variation of porosity (ϕ) when fluid can freely escape from the pores, i.e. pore pressure is absent. It can be expressed using the ratio of the bulk modulus of the porous body and the bulk modulus of the solid phase:

Biot’s modulus (M) is another important property of porous body in poroelasticity. It takes into account the coupling effect between the filling fluid and the porous body:

where ϕ 0 is the undeformed porosity; K f and K s are the bulk moduli of fluid and solid phases, respectively. Thus, the undrained bulk modulus (K u) of a porous body can be calculated as follows:

Now let us consider in detail a porous body subjected to thermal changes. First, we focus on the drained state, when pore fluid can leave the pores fast enough. In this case fluid pressure does not have a significant contribution to the stress and strain fields in the porous body. Therefore, the value of CTE of a porous body (α), will be equal to that of the solid phase (α s):

However, pore fluid cannot easily escape from the pores in case of a porous body with vastly low permeability, such as cement paste. Because CTE of pore fluid is significantly higher than CTE of solid, pressure is built up in the pores and released very slowly - because of low permeability. In this case, the immediate response of the porous body to the temperature changes is governed by undrained CTE (α u ), which is calculated in the following way:

where α f is linear CTE of the pore fluid, and α ϕ is linear CTE related to the porosity and is defined as follows:

Substituting the expressions (1–3) and (6) into the Eq. (5) and assuming that porosity is invariant with pressure (ϕ ≈ ϕ 0), porosity (ϕ), Biot’s coefficient (b) and Biot’s modulus (M) can be eliminated, and the following expression for the undrained coefficient of linear thermal expansion can be obtained:

This new Eq. (7) can be used now to calculate the undrained CTE of cement paste, assuming that CTE and bulk modulus of fluid and solid phases, and the undrained bulk modulus of the porous body are known. Undrained bulk modulus is, in fact, equal to the dynamic bulk modulus, which can be obtained from the ultrasonic pulse velocity measurements.

3 Materials and methods

In this research, the ultrasonic pulse velocity in cement paste was measured starting from the casting. The measured ultrasonic pulse velocity was used to calculate CTE of cement paste using the derived Eq. (7). Calculated CTE was compared to the literature data. As well, the calculated value of CTE was used to decouple thermal and autogenous deformations. The linear autogenous shrinkage of large 70 × 70 × 1000 mm prism, obtained in this way, was compared to the autogenous shrinkage measured by volumetric method, where temperature changes were less than 1 °C.

Cement paste with water to cement ratio of 0.33 was prepared using a pan mixer. Cement type was CEM I 52.2 N Portland cement with the loss on ignition of 4.12 % by weight and the specific surface area of 421.7 ± 40 m2/kg. The ultrasonic pulse velocity was measured on the top surface of the beam specimens with dimensions of 70 × 70 × 280 mm. The measurements started immediately after casting. The resonance ultrasonic transducers of 60 kHz were used. The specimens were demolded at 1 day, and cured in sealed conditions at 30 ± 2 °C. Four replicate specimens for the testing of dynamic elasticity modulus were used. For ultrasonic pulse velocity, standard deviation reached a maximum of 5 % at the time of setting, though at later ages it did not exceed 1 %.

The dynamic bulk modulus (K) can be calculated from ultrasonic pulse velocity (V) using the following formula [2, 15]:

where ρ is density, and ν is Poisson’s ratio. The density was measured according to ASTM C-138, and Poisson’s ratio was taken as 0.22 for the paste in hardened state—after final set as 0.50 for the paste in the fresh state—before initial set, and as a linear interpolation between these two states.

Linear shrinkage tests were conducted using the testing apparatus similar to that described in [18]. This system is characterized by complete automation and high accuracy of measurement. It allows starting deformation measurement immediately after the casting. The apparatus consists of detachable steel molds mounted horizontally on laboratory tables, allowing carrying over the molds to a vibration table. Both ends of the 70 × 70 × 1000 mm beam specimen were free, and displacements in each end were measured independently by a linearly variable displacement transducer (LVDT) connected to the computerized measuring system. Each displacement measuring cycle consisted of 1000 measurements during 1 ms and the result was averaged. By this means, precision of not worse than 0.001 mm was achieved. A Teflon sheet was placed in between to minimize friction between the mold and the specimen. The specimens were cured in a room at a constant temperature of 30 ± 1 °C in sealed conditions. The sealing was provided with polyethylene sheets, which covered the concrete by at least five layers. Temperature development due to heat of hydration was measured by means of three thermocouples, which were imbedded into the concrete at the time of casting. The maximum temperature gradient across the section of concrete sample was about 3 °C.

The procedure of volumetric measurement of autogenous shrinkage involved monitoring the weight of the cement paste sample in elastic membrane submerged in paraffin oil. The test method for volumetric autogenous shrinkage used in current research was similar to the method described by Lura and Jensen [23]. The weight of the samples submerged in paraffin oil was measured by a balance connected to a logging device. The resolution of volumetric method in the linear strain measurements was about 3 microstrain considering the typical sample size of 130 ml and the weighing precision of 1 mg. The cement paste sample was suspended in a 7-L steel cylindrical container filled with paraffin oil. For temperature stability, the container was placed in a large water bath. The test was carried out in a temperature-controlled room at 30 ± 1 °C. A maximum temperature increase of 1.0 °C was measured in duplicate samples by means of thermocouples.

4 Results and discussion

The dynamic bulk modulus calculated using ultrasonic pulse velocity measurements for the cement paste with a w/c ratio of 0.33, is given in Fig. 1. The age of cement paste in this and further figures is shown starting from the time of addition of water to cement. A continuous function is required for the calculations of the linear thermal expansion coefficient and the corresponding thermal deformations. With this in mind, the following mathematical function was used for curve fitting of the dynamic bulk modulus, after setting:

where t is the age of the cement paste from the water addition, and a, b, c and d are fitting parameters. Ultrasonic pulse velocity stayed constant in the period before setting. The time of the first increase in ultrasonic pulse velocity was recognized as the setting time or “time zero” [25]. “Time zero” is crucial for the interpretation of shrinkage as a potential for the induction of stresses. In Fig. 1, the fitted curve of the dynamic bulk modulus is plotted by dotted line.

In Fig. 2, the values of linear CTE calculated with the formula (7) using the values of dynamic bulk modulus from Fig. 1, are shown. In these calculations, the volumetric CTE of pore liquid was considered as the volumetric thermal expansion coefficient of water at 30 °C, which was taken as 3α f = 302.6 × 10−6 (°C)−1 [9]. A characteristic value of silicates α s = 8 × 10−6 (°C)−1 was adopted as linear CTE for the solid matrix [16]. The bulk modulus of the liquid phase was taken as the inverse of water compressibility K f = 2.2 GPa [9]. The bulk modulus of the solid phase was assumed as K s = 44 GPa [14, 24].

The literature data on CTE of cement pastes and mortars are given in Fig. 2 for the comparison with the experimental values [21, 22, 28]. It can be seen that the kinetics of the CTE development is similar to the data available in the literature. The initial values are constant, because the ultrasonic pulse velocity before the setting of cement paste does not change.

The linear thermal expansion coefficient calculated by Eq. (7) agrees well with the literature data in the time range from casting until the age of approximately 12 h, and reflects well the hydration kinetic and setting time of the tested cement pastes. However, the CTE value calculated by the proposed model does not reflect the increase of CTE due to self-desiccation at a later age, such as seen in the measurements of Loser et al. [21]. Strictly speaking, the simplified two-phase model of fully saturated cement paste is not capable to simulate self-desiccation. It is valid only for fully saturated porous body.

The effect of relative humidity, i.e. self-desiccation, on CTE is complex. Besides pure thermal dilation, the effect of the temperature on shrinkage and on relative humidity need to be considered [10, 27, 30]. Furthermore, temperature affects solubility of air and dissolved minerals in pore water, surface tension, viscosity of pore liquid and hydration rate of cement. To model self-desiccation, a further development of the model is required in order to introduce the gaseous phase; see for example unsaturated poromechanics in [5]. However, the simplicity of the model in this case will be lost. Yet, the simple model presented by Eq. (7) gives a good estimation of CTE during the early age for the assessment of thermal deformations around the time of solidification. To extend this model for CTE of unsaturated cement paste (α cp), an empiric correction function can be introduced:

where \( {\rm A}({\text{RH}}) \) is the relative CTE of cement paste as a function of relative humidity, i.e. CTE of unsaturated cement paste relative to the saturated CTE (α u) that is determined according to the method suggested above.

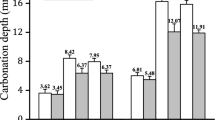

In Fig. 3, the comparison of the free shrinkage that was measured using linear and volumetric methods, is presented. The shrinkage values measured by volumetric method that are given in Fig. 3 were converted to linear deformations for proper comparison. The temperature measured in the linear shrinkage sample during the test is shown in Fig. 4. A temperature increase of approximately 15 °C was observed in the linear shrinkage sample, after casting. It can be seen in Fig. 3 that this temperature peak is also reflected in the measurements of linear shrinkage. Now, let us calculate the thermal deformations and subtract them from the linear shrinkage curves.

At this stage, we will not consider the coupling effect between autogenous shrinkage and temperature. However, the value of the coefficient of thermal expansion of water essentially depends on the temperature. Accordingly, in order to take into account this dependence in the Eq. (7), a polynomial fit was used. The polynomial fitting curve was calculated based on the data of Kell on the volumetric coefficient of thermal expansion of water at various temperatures [17]. The linear CTE calculated by this method, was used for assessment of the thermal deformations in the free linear shrinkage sample. The autogenous shrinkage deformations were calculated by subtracting the estimated thermal deformations from the total free shrinkage curve. The curves in Fig. 3 begin shortly after the casting, and, thus, include a part of the deformations preceding the setting time. However, for the analysis of the induced stresses in case of restrained deformations, the autogenous shrinkage has to be taken from the “time zero”. For this reason, the portion of the deformation prior to the “time zero” was removed. The resulting curves for autogenous shrinkage are shown in Fig. 5.

It can be seen from Fig. 5 that in general the final values of shrinkage after 3 days agree well between volumetric and linear measurements. Yet, there is a gap between volumetric and linear measurements at a very early age, since temperature changes not only lead to thermal deformations, but also affect the kinetics of hydration and autogenous shrinkage. The effect of temperature on the rate of hydration can be accounted using maturity approach [3], for example, applying the formula proposed by Hansen and Pedersen [12]. As can be seen in Fig. 5, the shrinkage curve measured by linear setup and corrected for thermal deformations and maturity lies very close to the shrinkage curve obtained by volumetric method. In maturity calculations activation energy of E a = 53 kJ/mol was used as measured by isothermal calorimetry [31].

We can see that the coefficient of thermal expansion estimated using ultrasonic pulse velocity allows us to evaluate successfully thermal deformations in the proximity of solidification time. This approach may be easily extended to concretes. The proposed formula, in conjunction with maturity concept, enables calculations to separate between thermal and autogenous deformations with a good approximation. Yet, it should be noted that maturity concept does not take into account the effect of temperature on autogenous shrinkage, for example temperature effect on the surface tension of water.

5 Conclusion

A novel approach to estimate the coefficient of thermal expansion of cementitious materials at early ages using ultrasonic pulse velocity measurements was proposed. The proposed approach gives results in the proximity of solidification time and can be successfully applied for decoupling of thermal and autogenous deformations. In order to predict the effect of self-desiccation, further development is required to include gaseous phase.

Change history

04 February 2019

The article Application of ultrasonic pulse velocity for assessment of thermal expansion coefficient of concrete at early age, written by Semion Zhutovsky, Konstantin Kovler, was originally published Online without Open Access.

References

Ai H, Young JF, Scherer GW (2001) Thermal expansion kinetics: Method to measure permeability of cementitious materials: II, application to hardened cement pastes. J Am Ceram Soc 84(2):385–391

Bungey JH, Millard SG (1995) Chapter 3. Ultrasonic pulse velocity methods. In: Testing of concrete in structures. Spon Press, London

Carino NJ, Lew HS (2001) The maturity method: from theory to application. In: Chang PC (ed) Proceedings of the 2001 structures congress, American Society of Civil Engineers, Washington, D.C.

Coussy O (2004) Poromechanics. Wiley, Chichester

Coussy O (2010) Mechanics and physics of porous solids. Wiley, Chichester

Coussy O, Brisard S (2009) Prediction of drying shrinkage beyond the pore isodeformation assumption. J Mech Mater Struct 4(2):263–279

Coussy O, Dangla P, Lassabatere T, Baroghel-Bouny V (2004) The equivalent pore pressure and the swelling and shrinkage of cement-based materials. Mater Struct 37(1):15–20

Detournay E, Cheng AD (1993) Fundamentals of poroelasticity. In: Fairhurst C (ed) Comprehensive rock engineering: principles, practice and projects, vol II, Analysis and Design Method, Pergamon Press, New York, pp 113–171

Eisenberg D, Kauzmann W (1969) The structure and properties of water. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Grasley ZC, Lange DA (2007) Thermal dilation and internal relative humidity of hardened cement paste. Mater Struct 40(3):311–317

Grasley ZC, Scherer GW, Lange DA, Valenza JJ (2007) Dynamic pressurization method for measuring permeability and modulus: II. Cementitious materials. Mater Struct 40(7):711–721

Hansen PF, Pedersen EJ (1977) Maturity computer for controlled curing and hardening of concrete. Nordisk Betong (In Danish) 1(19):21–25

Hashin Z (1969) Theory of composite materials in mechanics of composite materials. Pergamon Press, New York

Helmuth R, Turk D (1966) Elastic moduli of hardened Portland cement and tricalcium silicate pastes: effect of porosity. In: Symposium on structure of Portland cement paste and concrete (special report 90), Highway Research Board, Washington, DC, pp 135–144

Hueter TF, Bolt RH (1955) Sonics: techniques for the use of sound and ultrasound in engineering and science. Wiley, New York

Jahangirnejad S, Buch N, Kravchenko A (2009) Evaluation of coefficient of thermal expansion test protocol and its impact on jointed concrete pavement performance. ACI Mater J 106(1):64–71

Kell GS (1967) Precise representation of volume properties of water at one atmosphere. J Chem Eng Data 12(1):66–69

Kovler K (1994) Testing system for determining the mechanical behavior of early age concrete under restrained and free uniaxial shrinkage. Mater Struct 27:324–330

Kovler K, Jensen OM (2005) Novel technologies of concrete curing. Concrete Int 27(9):39–42

Kovler K, Zhutovsky S (2006) Overview and future trends of shrinkage research. Mater Struct 39(9):827–847

Loser R, Münch B, Lura P (2010) A volumetric technique for measuring the coefficient of thermal expansion of hardening cement paste and mortar. Cement Concrete Res 40(7):1138–1147

Loukili A, Chopin A, Khelidj A, Le Touzo J-Y (2000) A new approach to determine autogenous shrinkage of mortar at an early age considering temperature history. Cement Concrete Res 30(6):915–922

Lura P, Jensen O (2007) Measuring techniques for autogenous strain of cement paste. Mater Struct 40(4):431–440

Lura P, Jensen OM, van Breugel K (2003) Autogenous shrinkage in high-performance cement paste: an evaluation of basic mechanisms. Cement Concrete Res 33(2):223–232

Sant G, Dehadrai M, Bentz D, Lura P, Ferraris CF, Bullard JW, Weiss J (2009) Detecting the fluid-to-solid transition in cement pastes. Concrete Int 31(6):53–58

Scherer GW (2000) Thermal expansion kinetics: method to measure permeability of cementitious materials: I, theory. J Am Ceram Soc 83(11):2753–2761

Sellevold E, Bjøntegaard Ø (2006) Coefficient of thermal expansion of cement paste and concrete: mechanisms of moisture interaction. Mater Struct 39(9):809–815

Turcry P, Loukili A, Barcelo L, Casabonne JM (2002) Can the maturity concept be used to separate the autogenous shrinkage and thermal deformation of a cement paste at early age. Cement Concrete Res 32(9):1443–1450

Wyrzykowski M, Lura P (2013) Controlling the coefficient of thermal expansion of cementitious materials—a new application for superabsorbent polymers. Cement Concrete Compos 35(1):49–58

Wyrzykowski M, Lura P (2013) Moisture dependence of thermal expansion in cement-based materials at early ages. Cement Concrete Res 53:25–35

Zhutovsky S (2014) Mechanisms of internal curing of high-performance concrete, Ph.D. Thesis, Technion – Israel Institute of Technology, Haifa

Zhutovsky S, Kovler K (2015) Evaluation of the thermal expansion coefficient using non-destructive testing. In: Proceedings of 10th international conference on mechanics and physics of creep, shrinkage, and durability of concrete and concrete structures—CONCREEP 10, Vienna, pp 1137–1146

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhutovsky, S., Kovler, K. Application of ultrasonic pulse velocity for assessment of thermal expansion coefficient of concrete at early age. Mater Struct 50, 5 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1617/s11527-016-0866-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1617/s11527-016-0866-9