Abstract

Background

Ethiopian highland bamboo [Oldeania alpina (K. Schum) Stapleton] (Poaceae: Bambusoideae: Arundinarieae) is one of the economically and environmentally important plants in Ethiopia. Despite its wide presence in the country, nothing is known about genetic diversity and population structure of the species.

Methods

The study relied on 150 DNA samples representing 15 O.alpina populations collected across major O.alpina harboring forests of Ethiopia. Following total genomic DNA isolation SSR primer screening was conducted using PCR, gel electrophoreses, gel doc imaging, allele scoring, and statistical analysis. Accordingly nine SSR primers from Chinese Phyllostachys edulis and seven from Ethiopian Oxytenanthera abyssinica were found informative and used to investigate the extent of genetic diversity and structure of O.alpina populations.

Results

The study revealed the presence of moderate genetic diversity (Ho = 0.262; I = 0.639) within populations and very low genetic differentiation among populations (Fst = 0.019). Cluster (UPGMA), PCoA, and STRUCTURE analysis did not group the populations into clearly defined genetically distinct clusters according to their geographic origins, more likely due to the reproductive biology of the species since vegetative propagation is the main means of reproduction associated with 50–100 years of flowering and low viability of seeds.

Conclusions

Despite limitations connected with employing only 15 SSR markers, the study suggested the presence of moderate genetic diversity within populations and highly mixed population structure resulting in very low genetic differentiation among O. alpina populations. This information could serve as a basis for designing suitable conservation strategies and conducting further research using more SSRs and other sequences-based informative markers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bamboos are found in Asia, America, and Africa and belong to the family Poaceae and subfamily Bambusoideae. There are roughly 1670 species within 125 genera (Chaomao et al. 2006; Basak et al. 2021; Rohilla et al. 2023). Bamboos are one of the most versatile renewable resources in the plant kingdom. The majority of bamboos are distributed in tropical and subtropical climates around the world (Das et al. 2008; Qiao et al. 2014). In Africa, Madagascar is home to 43 bamboo species. Ethiopia, Tanzania, Malawi, Uganda, Sudan, and Zambia are among the African countries with bamboo resources. Only two species of bamboos are present in Ethiopia: Oldeania alpina (previously known as Arundinaria alpina or Yushania alpina) and Oxytenanthera abyssinica (Embaye 2003; Bekele 2007). Due to their excellent carbon fixation potential and high strength-to-weight ratio, bamboos are attracting more attention in the ecological and economic realms from time to time (Ohrnberger 1999; Fu 2001; Peng et al.2013). Furniture, fiber and textile poles, buildings, utensils, roofing material, food, pipes, animal fodder, ornamental, soil conservation, basketry and fence materials are a few of the bamboo uses. Because of easily splits, O. alpina is frequently used to make mats, chairs, sofas, and tables (Bekele 2007). Bamboo is an interesting model for addressing fundamental biological questions, due to its fastest-growing ability on earth, approximately two inches per hour and 60 feet in three months (Khalil et al. 2012), unique rhizome-dependent systems, expansion of gene families as a result of polyploidization, having both regular and irregular flowering habit followed by mass synchronous flowering and subsequent mass death (Tao et al. 2018; Guo et al. 2019; Zheng et al. 2020; Basak et al.2021).

Most of the woody bamboos studied are polyploids (Peng et al. 2013). Research indicated that the majority of woody bamboos have 12 (x = 12) chromosomes (Clark et al. 1995). Woody bamboos belong to two distinct polyploidy groups: temperate woody bamboos are primarily tetraploid (2n = 4x = 48) while tropical woody bamboos are primarily hexaploid (2n = 6x = 72). The findings by Gielis et al. (1997) confirmed that tropical woody bamboos have a higher genomic DNA content than temperate woody bamboos.

Plant genetic diversity, population genetic structure, genetic differentiation, cultivar identification, and evolutionary genetics all benefited from microsatellite markers, also known as simple sequence repeats (SSR). SSR are favored because they are polymorphic, co-dominant, have high information content, and are relatively abundant (Gui et al. 2007; Rohilla et al. 2023). SSR markers can be developed for plant species with entire genome sequences or by exploring existing SSRs from related species, as several plant species show sufficient homology between genomes in microsatellite-bearing regions (Kalia et al. 2011; Tu et al. 2011; Sataya et al. 2016). Despite losing the advantage of co-dominance in polyploid species, SSR markers remain a powerful tool for genotyping of polyploid species due to the vast number of reproducible alleles available per locus (Bhandawat et al. 2014, 2019; Meena et al. 2020). The distribution of SSR is determined by selection pressure during evolution, hence SSR markers from transcriptome data most likely offer a higher degree of resolution in population genetic studies (Du et al. 2013; Yang et al. 2022.) The flowering cycle of O. alpina is about 45–50 years, as a result, vegetative propagation is the most common means of reproduction. This tends to support the hypothesis that O. alpina populations reveal very low genetic differences among populations.

Appropriate conservation and exploitation strategies are devised based on the genetic diversity status of the species (Bhandawat et al. 2015). SSR markers have been developed for several bamboo species (Bhandawat et al. 2014; Zhao et al. 2015; Satya et al. 2016; Jiang et al. 2017) and have been used to determine genetic diversity; population differentiation and population structure of various bamboos species (Miyazaki et al.2009; Jiang et al.2013; Bhandawat et al. 2015; Rohilla et al. 2023). SSR markers developed from Phyllostachys edulis are highly conservative and transferrable to some closely related bamboo species (Liu et al. 2022). To examine the extent of genetic diversity, various statistical approaches including expected and observed heterozygosity, polymorphic information content and F statistics such as genetic differentiation, principal coordinate analysis, population structure, and analysis of molecular variance have been used. Despite conservation intervention of a species heavily relying on the knowledge of the genetic diversity status and the enormous ecological and economic importance of the species, the population genetic diversity status of O. alpina populations remains elusive. This research is conducted with the objective of investigating the degree of genetic diversity, population differentiation and structure of O. alpina populations, which could serve as an important input for conservation measures, utilization and further studies.

Materials and methods

Ethiopian highland bamboo (O. alpina) habitats and descriptions

Ethiopian highland bamboo (O. alpina) is a giant grass belonging to the tribe Arundinarieae, subfamily Bambusoideae, of the grass family Poaceae (Gramineae). O. alpina is harbored in the altitude range between 2200 and 3500 m above sea level, with temperatures ranging from 10 to 20 °C and annual rainfall ranging from 1500 to 2500 mm. It is common in Ethiopia’s moist agroclimatic zones, such as the Gojam, Shoa, Gedeo, Sidama, Awi, Illubabor, Gamo Gofa, Jima, Arsi and Bale zones (Liese 2008; Kidane et al. 2023). The woody grass according to (Bekele 2007) grows in dense stands with a leafy canopy and stems so close together that passing through is impossible. O. alpina is best described as a large hollow-stemmed grass that grows to a height of 6–8 m but can reach 12–25 m. The stems (culms) are smooth, woody, hollow, yellow-green to brown, growing from swollen underground stems (rhizomes). Stems can reach 7–10 cm in diameter (Liese 2008; Mulatu 2021). In various regions of Ethiopia, there is no well-documented information about the flowering cycle of O.alpina, however, it has been reported that in the Kosober/Injibara area of Northwest Ethiopia O. alpina has been flowering gregariously and intermittently in small patches without being recognized by the general public for three decades (Sertse et al. 2011).

Plant materials and sample collections

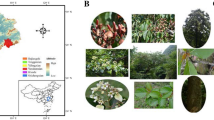

Young leaf samples from 150 Ethiopian O. alpina plants, representing 15 populations (10 samples from each population) were collected separately and gently dried using silica gel. The distance between the two samples was dependent on the width of the forest. Each sample was composed of ~ 12 leaves inserted with silica gel in the zipped plastic bag, which corresponds to 120 leaves from each locality/population. Samples were collected to cover the country’s major O. alpina growing areas (Table 1 and Fig. 1). The habitat and stand structure of O. alpina populations are displayed in (Fig. 2).

Genomic DNA extraction and SSR marker screening

Total genomic DNA was extracted from 50 mg silica gel dried young leaves using a modified CTAB protocol as described by Doyle and Doyle (1987). A Nanodrop spectrophotometer (ND-8000, Thermo Scientific) and 1% percent agarose gel electrophoresis were used to check the quantity and quality of the isolated DNA. After screening and procedure optimization a total of 16 SSRsprimer pairs (9 from Phyllostachys edulis and 7 from Oxytenanthera abyssinica (Zhao et al. 2015; Adem et al. 2019)) with clear and reproducible bands were selected and used to investigate the within and among the population genetic diversity and structure of O. alpina (Table 2).

PCR, agarose gel electrophoresis and SSR alleles scoring

PCR amplification was done in a 12.5 μl reaction, containing a mixture of 2 μl of genomic DNA,

1 μl of each of the two primers (at a concentration of 10 μM), 2.25 μl nuclease-free water and 6.25 remaining PCR components. The temperature profile used during the amplification consisted of 5 min of preheating at 94 °C followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 54 °C for 30 s, extension at 72 °C for 30 s, and a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. To observe DNA fragments, ten microliters of PCR amplified products were fractionated by 3% agarose gel electrophoresis using 1X TAE buffer at 130 V for 3 h. The gel was stained using gel red (2 μl). A 50/100 bp Biolabs DNA ladder was used to estimate the amplification size. The Altay UVP gel documentation system was then used to image the fragments. The clear bands were recognized as alleles for the SSR loci based on the expected PCR product size of each primer. Heterozygote alleles were scored as bands amplified with different PCR product sizes (bP), while homozygous alleles as bands produced with uniform size (Additional file 1).

Genotypic data analysis

The number of alleles per locus, expected and observed heterozygosity, Polymorphic Information Content (PIC) and F statistics such as genetic differentiation (Fst), Wrights fixation index (Fis), principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) for the 15 populations were conducted using GenAlEx 6.502 (Peakall and Smouse 2012). Analysis of Molecular Variance (AMOVA) was conducted using ARLEQUIN ver 3.5 (Excoffier and Lischer 2011). UPGMA for the 15 O. alpina groups was drawn using the Poptree2 (http://www.ualberta.ca/~fyeh/fyeh) program. Genetic distance and genetic identity between 15 O.alpina populations were computed using Darwin V6 software. Based on their computed pairwise genetic distance value, a dendrogram was drawn for the 15 O.alpina populations by using Darwin V6 software (Perrier and Jacquemoud-Collet, 2006).

A Bayesian model-based clustering algorithm in STRUCTURE ver. 2.3.4 (Pritchard et al. 2000; Falush et al. 2003) was employed to detect admixture and infer the pattern of population structure. To decide the most likely number of populations (K), a burn-in period of 50,000 was used in each run, and data were collected over 500,000 Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) replications for K = 1 to K = 15 using 20 iterations for each K. The optimum K value was predicted following the simulation method of (Evanno et al. 2005) using the web-based STRUCTURE HARVESTER ver. 0.6.92 (Earl and Holdt 2012).The bar plot for the optimum K was determined using Clumpak beta version (Kopelman et al. 2015). Gene flow of the populations (Nm) was calculated based on Fst, Nm = [(1/Fst)−1]/4.

Results

SSR genotyping and the extent of genetic diversity

A total of 49 alleles were detected in the 150 O. alpina individuals, ranging from 2 (primers Phe453 and Oxa5) and to 4 (primers Phe734, Phe317 and Oxa1), with an average of 3.06 alleles per locus with overall moderate genetic diversity (Ho = 0.262) as presented in (Table 3). Two-thirds of the major allele frequencies were covered by thirteen of the sixteen markers. The studied loci indicated significant differences between Ho and He, demonstrating a heterozygosity that differed significantly from Hardy Weinberg Equilibrium across populations. All of the employed markers have polymorphism information content scores greater than 0.5 (0.812–1).

The observed number of alleles (Na), effective number of alleles (Ne), observed heterozygosity (Ho) and expected heterozygosity (He) and Fixation index (F) are presented in (Table 4). Individual populations had Na values ranging from 2.063 (Agaro) to 2.563 (Debresina and Rira). The Ne value ranges from 1.587 (Agaro) to 2.046 (Debresina), with a mean Na of 2.366 and Ne of 0.179. The Ho values ranged from 0.198 (Kosober) to 0.353 (Masha). Masha possessed the highest genetic diversity (Ho = 0.353; I= 0.693).

Genetic distance and identity among the fifteen O.alpina populations of Ethiopia

For each pair of the fifteen highland bamboo populations, genetic identity was determined according to Nei (1972). The highest genetic identity (0.980) was observed between Agaro and Konta, while the highest genetic distance (0.091) was observed between Chencha and Debresina populations. Based on Nei-Li’s similarity index, a high similarity rate was observed suggesting a close relationship among populations.

Genetic differentiation, gene flow and variance analysis of O.alpina populations

Analysis of Molecular Variance (AMOVA) among 15 populations revealed that variations were highly distributed within populations (98%) rather than among populations (2%) (Table 5). O. alpina populations exhibited genetic differentiation (Fst = 0.019) and gene flow (Nm = 12.91) between populations. Paired comparisons among populations based on locus-by-locus analysis for the 16 microsatellite loci revealed that Fst ranged from 0.000 at locus Phe453 to 0.265 at locus Phe82. The highest genetic identity (0.980) was observed between Agaro and Konta, while the highest genetic distance (0.091) was observed between Chencha and Debresina populations.

Population structure, principal coordinate and cluster analysis

The Bayesian approach-based assignment of the 150 individual plants to different groups using STRUCTURE outputs, predicted (K = 6) to be the most likely number of clusters (Fig. 3a). Based on this value, Clum pak result (bar plot) shows the mixed genetic structure of populations (Fig. 3b).

Principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) bi-plot shows the highly intermixed pattern of 150 individuals representing 15 populations. In the PCoA, the first three principal coordinates accounted for 25.36% of the total variation. The first principalt coordinate accounted for 9.85% of the total variation, while the second and third principal coordinates accounted for 8.07% and 7.44% respectively of the total molecular variance (Fig. 4).

UPGMA-based population phylogeny clustered the 15 populations into 2 main clusters (1 and 2) followed by 5 sub-clusters (A, B, C, D, and E) (Fig. 5).

Discussion

SSR genotyping and extent of genetic diversity

The nature of their hypervariability, high abundance of information, and codominance make SSRs an interesting marker for population genetics and germplasm identification studies in plants (Yang et al.022; Liu et al. 2022; Rohilla et al. 2023). The geographic range of a species, the timing of its flowers, and its mating strategy are all factors that affect its genetic diversity (Hamrick and Godt 1996; Nyborn 2004). Other elements that may control the genetic diversity within a species include population size, gene flow, and genetic drift (George et al. 2009). The flowering of O. alpina is only once every 45–50 years, hence vegetative propagation is the most common form of reproduction. This tends to back a hypothesis that claims the occurrences of low genetic diversity within O. alpina populations. The study results, however, debunked the hypothesis by showing that O. alpina populations have exhibited moderate genetic diversity within populations.

For O. alpina populations, there is no prior information on the molecular marker-based genetic diversity in general and SSR marker analysis in particular. The total number of 49 alleles, 2–4 per loci from this study was better than 28 for Guadua inermis, 25 for G. amplexifolia and 13 G. tuxtlensis (Pérez-Alquicira et al. 2021), comparable with 64 alleles ranging from 2 to 5 per loci that were detected using 23 SSR primers in P. edulis (Zhao et al.2015). However, lower than, 89 alleles of 5.93 per loci (Sataya et al. 2016), 89 alleles within a range of 2–16 loci in P. edulis (Liu et al. 2022) and 169 alleles were detected across 20 SSRs in P. edulis (Jiang et al. 2017). Cai et al. (2019) found 3–12 alleles for P.violascens and 3–20 for Phyllostachys using EST-SSR primers. This reveals that the number of alleles to be detected significantly varies not only in different species but also within the same species due to the use of genetic materials from different sources (Zhao et al. 2015). This study found no appreciable polymorphism variations between the SSR markers transferred from the two species, even though transferability and polymorphism rely on the genomic position of the markers (Lin et al. 2014).

The genetic diversity expressed in terms of expected heterozygosity was high for both loci and population (He = 0.399 and 0.398) respectively. However, that of observed heterozygosity is a bit lower, 0.261 for populations and 0.262 for loci. As a species with odd reproductive biology, these values are taken as a good indicator of genetic diversity (Ramanayake 2006). Compared with other studies, the polymorphic information content (PIC = 0.92) shows the loci's high information content and polymorphism. For instance, Liu et al (2022) presented a PIC of 0.46, Silva et al. (2020) found a PIC of 0. 50. Jiang et al. (2017) found a PIC of 0.74. Several species of bamboos evaluated by Chen et al. (2010) showed a PIC that ranges from 0.48 to 0.987, these values are better close to this study. As PIC informs the polymorphic level of the markers, any marker (PIC > 0.50) is suitable for genetic diversity study (Lin et al. 2014; Satya 2016).

Despite agarose gel electrophoreses being used as a method for fractionation of SSR amplicons, the detected moderate genetic diversity from this study is higher than those reported in the genetic diversity analysis of saplings after a mass flowering of bamboo in the Brazilian Atlantic Forest (Ho = 0.191 for seedlings, Ho = 0.059 for saplings) based on nuclear SSR markers (Aberu et al. 2014). However, the result is consistent with the majority of the research findings. Using 42 SSR markers Sharma et al. (2008) found genetic variability (Ho = 0.250) in Dendrocalamus hamiltonii. Reyes et al. (2015) observed genetic variation (Ho = 0.253) in Bambusa blumeana and (Ho = 0.265) in Dendrocalamus hamiltonii (Meena et al. 2018). Similarly, moderate genetic diversity (Ho = 0.376) was detected in SSR analysis of P. edulis (Jiang et al. 2017) and Pérez-Alquicira et al. (2021) found (Ho = 0.330) in G. Tutlensis, (Ho = 0.210) in G. amplexifolia, (Ho = 0.200) in G. Inermis in three Mexican bamboos. Jiang et al. (2013) found (Ho = 0.500, I = 0.532) based on 20 SSR markers in P. edulis. Jiang et al. (2017) presented (Ho = 0.376, I = 0.500, PIC = 74.4%) for 34 P. edulis populations using 20 SSR markers. Genetic diversity study of Fargesia denudata using 15 SSR markers showed heterozygosity Ho = 0.420 (Lv et al. 2016). The analysis using 14 SSR markers showed (Ho = 0.461) for Fargesia spathacea (Huang et al. 2020). Genetic diversity showed (Ho = 0.567) within populations of Dendrocalamus sinicus using eight SSR markers (Yang et al. 2018). Analysis using 17 SSR markers resulted in (Ho = 0.430) for Guadua aff. chaparensis populations and (Ho = 0.39) for G. aff. lynnclarkiae populations in Brazil (Silva et al. 2020). As reported by Attigala et al. (2017) Srilanka’s Kurunadebilis showed (Ho = 0.758) using 12 SSR markers.

These differences may be more pronounced due to the homoplasy of SSR markers, sampling strategy, sample size, and sources of the genotyping material since materials of the same species collected in different areas and times have exhibited a significant difference in their genetic status (Zhao et al. 2015). This could occur after a lack of genetic variation (Wong 2004). Due to having reduced genetic differentiation among populations but moderate to higher genetic variations within populations of the same species, such genetic characteristics are attributed to self-incompatibility, outcrossing and long-lived plants (Hammrick et al. 1992; Zawko et al.2001; Rohilla et al. 2023). O. alpina is a long-lived woody bamboo species, with a long vegetative phase (Sertse et al. 2011; Isagi 2016) there is likely to be a moderate amount of genetic variation within the populations as shown in other bamboos (Jiang et al. 2013, 2017). Nybom (2004) found that the majority of the genetic variability was conserved within populations of long-lived and outcrossing plants using sequence-tagged microsatellite marker analyses.

Genetic differentiation,gene flow and analysis of variance

Analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) revealed that the highest genetic variability (62.98%) was accounted for within individuals than among populations (1.99%). The Nei-Li’s similarity index also revealed a high rate of similarity suggesting a close relationship among populations. This is not consistent with similar studies on bamboos that detected 14.55% among populations and 84.55% within populations (Jiang et al. 2017) and 71.74% among populations and 28.25% within populations (Pérez-Alquicira et al. 2021).

According to Wright (1978) Fst value classification, a very low level of genetic differentiation (Fst = 0.019) was obtained. Only one study shows lower Fst than the current study (Fst = 0.01) for Guadua amplexifolia (Pérez-Alquicira et al. 2021). This implies that genetic differentiation was poorly pronounced. In the SSR analysis of Mexican bamboos, Pérez-Alquicira et al. (2021) found genetic differentiation of (Fst = 0.04) for G. tuxtlensis and (Fst = 0.29) for G. Inermis. Kuruna debilis populations in Sri Lanka showed genetic differentiation (Fst = 0.113) using SSR Markers (Attigala et al. 2017). In the SSR study of Phyllostachys edulis, (Fst = 0.162) was found (Zhao et al. 2015). Very high genetic differentiation was found (Fst = 0.847) for Dendrocalamus giganteus (Tian et al. 2012), (Fst = 0.338) for Dendrocalamus hamiltonii (Nilkanta et al. 2017). According to Abreu et al. (2014), genetic differentiation among seedlings and saplings of Brazilian bamboo after a mass flowering was (Fst = 0.31) for the chloroplast SSR. Using eight SSR markers, Yang et al. (2022). Found (Fst = 0.306) in Dendrocalamus sinicus. According to Grant (1991), genetic differentiation and population gene flow are inversely correlated. The result supported the previous assertion of high gene flow (Nm = 12.91) despite the very poor or non-existent seed dispersal mechanism of O. alpina populations. SSR analysis of Melocanna baccifera populations reported gene flow (Nm = 2.545) (Zawko et al. 2001) and (Nm = 1.203) in Phyllostachys edulis (Zhao et al. 2015). Overall gene flow (Nm = 0.49) among all the populations of Indian Dendrocalamus hamiltonii populations (Nilkanta et al. 2017). However, the same study observed high gene flow (Nm = 1.73) between Kangra and Mandi populations of Indian localities, while Mandi and Mizoram recorded low gene flow (Nm = 0.26).

The ability of a species to develop genetic variation across its range depends in large part on the spatial organization of local populations and the associated patterns of gene flow (Ennos 1991). Pollen drift and seed dispersal could not be the most likely reason for gene exchange across populations over a great distance due to limited pollen dispersion brought on rare flowering, a naturally protracted vegetative phase and changes in flowering times (Sertse et al. 2011; Zhang and Ma 1990). However, such high value ofgene flow might be attributed to the fact that O. alpina populations have likely undergone massive distribution of vegetative parts to different areas probably many years ago. The population structure, principal coordinate and cluster analysis show the mixing and overlapping of O.alpina individuals from various populations. According to Chen et al. (2014) plants that are close to one another retain higher genetic identity than those far from each other. Similar to this, the highest genetic identity (0.980) was observed between Agaro and Konta (157 km), which are much closer geographically than those with the highest genetic distance (0.091) observed between Chencha and Debresina (632 km). This would have been more acceptable if the highest genetic identity occurred between Ankober and Debresina populations due to their very closer distance of 97 km than any other populations.

Population structure, principal coordinate and clustering

As shown from Delta K, for STRUCTURE analysis, the most likely cluster for 15 populations is (K = 6) with a high intermix of individuals. Little intermix (K = 2 and 3) clusters were found in G. amplexifolia, G. Inermis and G. tuxtlensis populations of Mexican bamboos (Pérez-Alquicira et al. 2021). The structure analysis of Brazilian 347 bamboo individuals formed (K = 5) distinct groups, showing little intermix among populations (Silva et al. 2020). The principal coordinate analysis shows that individuals from a single population were extensively dispersed and difficult to form groups as a result of significant genetic admixture, most likely due to sharing similar vegetative reproduction material probably many years back. Gene flow which relies on seed dispersal and pollen drift is the unlikely reason for such high genetic admixture since the flowering of O.alpina populations requires up to five decades and seed viability is very low (Shewaye et al. 2019). There is no well-documented information about the difference in flowering, pollen dispersal and seed flow between the sampled populations except that the O. alpina population of the Injibara area has been flowering every three- to five-year intervals (Sertse et al. 2011). Other sampled populations are thought to take decades to flower.

The Unweighted Pair Group with Arithmetic Mean (UPGMA) analysis of SSR data depicted that 15 populations were clustered into two main and five sub-clusters. However, the clustering does not coincide with their geographic origins. The UPGMA analysis by Liu et al. (2022) clustered 34 bamboo accessions into two groups using 15 SSR markers. The study showed that the majority of the accessions were grouped based on their taxonomic classifications. However, the used primer sets could not distinguish some accessions accordingly, pointing to the limitation of the employed SSR markers (Liu et al. 2022). Likewise, the SSR markers used in this study were not able to discriminate the populations according to their geographical origin or proximity to each other. This is in contrary to the prediction that plant populations often have a close genetic structure at short distances (Ennos 2001).

Limitations

The use of fewer SSRs and agarose gel, which might not be able to adequately distinguish the tiny changes between SSR amplicons, may be the cause of the populations’ relatively very low genetic differentiation but substantial genetic diversity within a population. Therefore, more research should concentrate on employing representative, distinct O. alpina populations, a greater number of SSRs that can capture the species' entire genetic diversity, and a capillary electrophoresis technique for improved SSR amplicon discrimination. Additionally, to better understand the genetic diversity and population dynamics of O. alpina populations, future research should develop the species' own SSR markers.

Conclusions

The study demonstrated the presence of moderate genetic diversity within populations and very low genetic differentiation among populations. Despite the Bayesian structure analysis forming six groups (K = 6) from 15 analyzed populations, distinct groups are not generated as also confirmed by UPGMA and PCoA analysis. Despite conservation measures being important for all populations this study suggests that Masha and Tikurcheni populations should be prioritized for in situ conservation. More detailed studies should focus on isolated populations that exhibit distinctive morphology may assist in knowing the assertions of morphological variations. This is important since molecular-based diversity analysis enables to re-evaluate traditional taxonomy that relies on vegetative features in bamboo.

Availability of data and materials

The raw SSR data is accompanied by the submission.

References

Abreu AG, Grombone-guaratini M, Val TM, Zucchi MI. Genetic diversity and age class structure of seedlings and saplings after a mast flowering of bamboo in the Brazilian atlantic forest. Int J Plant Sci. 2014;175:319–27.

Adem M, Beyene D, Feyissa T, Zhao K, Jiang T. De novo assembly and transcriptome profiling of Ethiopian lowland bamboo [Oxytenanthera abyssinica (A.Rich) Munro] under drought and salt stresses. Open Biotechnol J. 2019;13:6–17. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874070701913010006.

Attigala L, Gallaher T, Nason J, Clark LG. Genetic diversity and population structure of the threatened temperate woody bamboo Kuruna debilis (Poaceae: Bambusoideae Arundinarieae) from Sri Lanka based on microsatellite analysis. J National Sci Found Sri Lanka. 2017;45:53–65.

Basak M, Dutta S, Subhadee P, Biswas B, Sukanya CS, Sarka A, Rahaman T, Dey S, Biswas P, Das M. Genomic insights into growth and development of bamboos: what have we learnt and what more to discover? Trees. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00468-021-02197-6.

Bekele A. Useful Trees and Shrubs of Ethiopia: identification, propagation and management in 17 Agroecological Zones. Nairobi: RELMA in ICRAF Project; 2007.

Bhandawat A, Sharma V, Sharma H, Sood A, Sharma RK. Development and cross transferability of functionally relevant micro-satellite markers in Dendrocalamus latiflorus and related bamboo species. J Genet. 2014;93:e48-55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12041-014-0377-.

Bhandawat A, Singh G, Raina AS, Kaur J, Sharma RK. Development of genic SSR marker resource from RNASeq data in Dendrocalamus latiflorus. J Plant Biochem Biotechnol. 2015;25:179–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13562-015-0323-9.

Bhandawat A, Sharma V, Singh P, Seth R, Nag A, Kaur J, Sharma RK. Discovery and utilization of EST-SSR marker resource for genetic diversity and population structure analyses of a subtropical bamboo. Dendrocalamus Hamiltonii Biochem Genetics. 2019;57:652–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10528-019-09914-4.

Cai K, Zhu L, Zhang K, Li L, Zhao Z, Zeng W, Lin X. Development and characterization of EST-SSR Markers From RNA-Seq Data in Phyllostachys violascens. Front Plant Sci. 2019;10:50. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2019.00050.

Chaomao H, Weiyi L, Xiong Y, Yuming Y. Bamboo for the environment and trade: environmental benefits of bamboo forests and the sustainable development of bamboo industry in Western China. 2006.

Chen L, Chen F, He S, Ma L. High genetic diversity and small genetic variation among populations of Magnolia wufengensis (Magnoliaceae), revealed by ISSR and SRAP markers. Electron J Biotechnol. 2014;17:268–74.

Clark LG, Zhang W, Wendel JF. A phylogeny of the grass family (Poaceae) basedon ndhF sequence data. Syst Bot. 1995;20:436–60.

Das SM, Bhattacharya P, Singh S, Filgueiras P. Bamboo taxonomy and diversity in the era of molecular markers. Adv Bot Res. 2008;47:225–68.

Doyle JJ, Doyle JL. A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf tissue. Phytochem Bull. 1987;19:11–5.

Du Q, Pan W, Xu B, Li B, Zhang D. Polymorphic simple sequence repeat (SSR) loci within cellulose synthase (PtoCesA) genes are associated with growth and wood properties in Populus tomentosa. New Phytol. 2013;197:763–76.

Earl DA, Von Holdt BM. STRUCTURE HARVESTER: a website and program for visualizing STRUCTURE output and implementing the Evanno method. Conservat Genetic Resour. 2012;4:359–61.

Embaye K. Ecological aspects and resource management of bamboo forests in Ethiopia Doctoral dissertation, ISSN 1401–6230. Uppsala, Sweden: Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences; 2003.

Ennos R. Inference about spatial processes in plant populations from the analysis of molecular markers. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 2001.

Evanno G, Regnaut S, Goudet J. Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software STRUCTURE: a simulation study. Mol Ecol. 2005;14:2611–20.

Excoffier L, Lischer H. An Integrated Software Package for Population Genetics Data analysis. 2011.

Falush D, Stephens M, Pritchard JK. Inference of population structure using multi-locus genotype data: linked loci and correlated allele frequencies. Genetics. 2003;164:1567–87.

Fu H. Chinese Moso Bamboo: its importance. Bamboo. 2001;22:5–6.

George S, Sharma J, Yadon VL. Genetic diversity of the endangered and narrow endemic Piperia Yadonii (Orchidaceae) assessed with ISSR polymorphisms”. Am J Bot. 2009;96:2022–30.

Gielis J, Valente P, Bridts C, Verbelen P. Estimation of DNA content of bamboos using flow cytometry and confocal laser scanning. In: Chapman G, editor. Linnean Society Symposium Series 19. London: Academic press; 1997. p. 215–23.

Grant V. The evolutionary process: a critical study of evolutionary theory. NewYork: Columbia University Press; 1991.

Gui Y, Wang S, Quan L, Zhou C, Long S, Zheng H, Jin L, Ma N, Fan LJ. Genome size and sequence composition of moso bamboo: a comparative study. Sci China Life Sci. 2007;50:700–5.

Guo ZH, Ma PF, Yang GQ, Hu JY, Liu YL, Xia EH. Genome sequences provide insights into the reticulate origin and unique traits of woody bamboos. Mol Plant. 2019;12:1353–65.

Hamrick J, Godt M. Effects of life history traits on genetic diversity in plant species. Philoso Trans Royal Soc London Biol Sci. 1996;351:1291–8.

Hamrick JL, Godt M, Sherman-Broyles SL. Factors influencing levels of genetic diversity in woody plant species. In: population genetics of forest trees. New Forests. 1992;6:95–124.

Huang L, Xing XC, Li WW, Zhou Y, Zhang YQ, Xue C, Ren Y, Kang JQ. Population genetic structure of the giant panda staple food bamboo (Fargesia spathacea complex) and its taxonomic implications. J Syst Evol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1111/jse.12594.

Isagi Y, Oda T, Fukushima K, Lian C, Yokogawa M, Kaneko S. Predominance of a single clone of the most widely distributed bamboo species Phyllostachys edulis in East Asia. J Plant Res. 2016;129:21–7.

Jiang X, Zhang J, Ding L. Development of polymorphic microsatellite markers for Phyllostachys edulis (Poaceae), an important bamboo species in China. Appl Plant Sci. 2013. https://doi.org/10.3732/apps.1200012.

Jiang W, Bai T, Dai H, Wei Q, Zhang W. Microsatellite markers revealed moderate genetic diversity and population differentiation of Moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis) a primarily asexual reproduction species in China. Tree Genetics Genomics. 2017;13:130.

Kalia K, Rai K, Kalia S, Singh R, Dhawan K. Microsatellite markers: an overview of the recent progress in plants. Euphytica. 2011;177:309–34.

Khalil A, Bhat M, Jawaid MA, Hermawan MA, Hadi YS. Bamboo fibre reinforced biocomposites: a review. Mater Des. 2012;42:353–68.

Kidane B, Anjulo A, Mulatu Y, Reza S, Getahun A, Mulat S, Teshome U, Abere M. Species site matching of highland bamboo (Oldeania alpina) in Ethiopia. Heliyon. 2023;9(3):e13593. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e13593.

Kopelman NM, Mayzel J, Jakobsson M, Rosenberg NA, Mayrose I. CLUMPAK: a program for identifying clustering modes and packaging population structure inferences across K. Mol Ecol Res. 2015;15:1179–91.

Liese W. Bamboo plantations, the two Bamboos of Ethiopia. 2008.

Lin Y, Lu JJ, Wu D, Zhou B, Fang W, Ide Y, Tang DQ. Identification, cross-taxon transferability and application of full-length cDNA SSR markers in Phyllostachys pubescens. Springer plus. 2014;3:486.

Liu Y, Xiao X, Li G, Zhu C, Yang K, Feng X, Lou Y, Gao Z. Comprehensive analyses of simple sequence repeat (SSR) in bamboo genomes and development of SSR markers with peroxidase genes. Genes. 2022;13:1518. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes13091518.

Lv Y, Yu T, Lu S, Tian C, Li J, Du FK. Development of microsatellite markers for Fargesia denudata (Poaceae), the staple-food bamboo of the giant panda. Appl Plant Sci. 2016;4(6):1600005.

Meena K, Bhandari S, Kant BS, Ginwal S. Assessment of the genetic diversity of Dendrocalamus Hamiltonii along altitudinal gradient. Int J Genetics. 2018;10:501–6.

Meena K, Bhandari S, Ginwal S. Usage of microsatellite markers for characterization of polyploids: a case study in reference to hexaploid bamboo species. Silvae Genetica. 2020;69:94–7.

Miyazaki Y, Ohnishi N, Takafumi H, Hiura T. Genetics of dwarf bamboo do not die after one flowering event: evidence from genetic structure and flowering pattern. J Plant Res. 2009;122:523–8.

Mulatu Y. Bamboo seed sourcing and selection study in Ethiopia. INBAR Working Paper. Research program on Forests, Trees and Agroforestry. 2021.

Nilkanta H, Amom T, Tikendra L, Rahaman H, Nongdam P. ISSR marker based population genetic study of Melocanna baccifera (Roxb) Kurz: a commercially important bamboo of Manipur North-East India. Sci Africa. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/3757238.

Nybom H. Comparison of different nuclear DNA markers for estimating intraspecific genetic diversity in plants. Mol Ecol. 2004;13:1143–55.

Ohrnberger D. The bamboos of the world. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1999. p. 585.

Peakall R, Smouse PE. GenAlEx 6.5: genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research-an update. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:2537–9.

Peng Z, Lu Y, Li L, Zhao Q, Feng Q. The draft genome of the fast-growing non-timber forest species Moso bamboo (Phyllostachys heterocycla). Nat Genetics. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.2569.

Pérez-Alquicira J, Aguilera-López S, Rico Y, Ruiz-Sanchez E. A population genetics study of three native Mexican woody bamboo species of Guadua (Poaceae: Bambusoideae: Bambuseae: Guaduinae) using nuclear microsatellite markers. Bot Sci. 2021;99:542–59. https://doi.org/10.17129/botsci.2795.

Pritchard JK, Stephens M, Donnelly P. Inference of population structure using multi-locus genotype data. Genetics. 2000;155:945–59.

Qiao G, Yang H, Han X, Liu M, Jiang J, Jiang Y. Enhanced cold stress tolerance of transgenic Dendrocalamus latiflorus Munro (Ma bamboo) plants expressing a bacterial CodA gene. Vitro Cell Develop Biol Plant. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11627-013-9591-z.

Ramanayake S. Flowering in bamboo: an enigma! Ceylon J Sci. 2006;35:95–105.

Reyes A, Nocum L, Sumague V, Baja-Lapis B Assessment of Genetic Diversity of Kauayantinik (Bambusa blumeana Schultes f.) from Five Plantations in the Philippines through Transferability of SSR Markers. 10th World Bamboo Congress, Korea. 2015.

Rohilla S, Ginwal HS, Rana V. Genome-wide discovery of single- and multi-locus simple sequence repeat markers and their characterization in Dendrocalamus strictus: a commercial polyploid bamboo species of India. Genet Resour Crop Evol. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10722-023-01777-4.

Satya P, Paswan PK, Ghosh S, Majumdar S, Ali N. Co-familiar transferability of simple sequence repeat (SSR) markers from cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) and Jute (Corchorus olitorius.) to twenty-two Malvaceous species. 3 Biotech. 2016;6:65.

Sertse D, Disasa T, Bekele K, Alebachew M, Kebede Y. Mass flowering and death of bamboo: a potential threat to biodiversity and livelihoods in Ethiopia. J Biol Environ Sci. 2011;1:16–25.

Sharma K, Gupta P, Sharma V, Sood A, Mohapatra T. Evaluation of rice and sugarcane SSR markers for phylogenetic and genetic diversity analyses in bamboo. Genome. 2008;51:91–103.

Shewaye DA. Mass flowering and death of Arundinaria alpina (highland bamboo) impact on the livelihood of rural community: the case of Gedeo Zone, Southern Ethiopia. Ethiopian J Environ Develop. 2019;2(1):46–62.

Silva SMM, Martins K, Costa FHS, Campos TD, Scherwinski-Pereira JE. Genetic structure and diversity of native Guadua species (Poaceae: Bambusoideae) in natural populations of the Brazilian Amazon rainforest. Ann Brazilian Acad Sci. 2020;92:e20190083. https://doi.org/10.1590/0001-3765202020190083.

Sy C, Lin Y, Lin C, Chen W, Yang C, Ku H. Transferability of rice SSR markers to bamboo. Euphytica. 2010;175:23–33.

Tao G, Fu Y, Zhou M. Advances on molecular in studies mechanisms of rapid growth of bamboo species. Agric J Biotechnol. 2018;26:871–87.

Tian B, Yang HQ, Wong KM, Liu AZ, Ruan ZY. ISSR analysis shows low genetic diversity versus high genetic differentiation for giant bamboo, Dendrocalamus giganteus (Poaceae: Bambusoideae), in China populations. Genetic Resour Crop Evol. 2012;59:901–8.

Tu DP, Wei ZW, Wu ZN, Lei YF, Zhang D. Distribution characteristics and marker exploitation of EST-SSRs in Medicagom truncatula. Pratacult Sci. 2011;28:746–52.

Wong K. Bamboo the amazing grass. A guide to diversity and study of bamboo in Southeast Asia. Rimba Ilmu Botanic Garden. Kuala Lumpur: University of Malaya; 2004. p. 98.

Wright S. Evolution and the genetic of population, variability within and among natural populations, vol. 4. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1978.

Yang JB, Dong YR, Wong KM, Gu ZJ, Yang HQ, Li DZ. Genetic structure and differentiation in Dendrocalamus sinicus (Poaceae: Bambusoideae) populations provide insight into evolutionary history and speciation of woody bamboo. Sci Rep. 2018;8:16933. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-35269-8.

Yang Q, Jiang Y, Wang Y, Han R, Liang Z, He Q, Jia Q. SSR loci analysis in transcriptome and molecular Marker development in Polygonatum sibiricum. Biomed Res Int. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/4237913.

Zawko G, Krauss SL, Dixon KW, Sivasithamparam K. Conservation genetics of the rare and endangered Leucopogon obtectus (Ericaceae). Mol Ecol. 2001;10:2389–96.

Zhang W, Ma N. Vitality of bamboo pollens and natural pollination in bamboo plants. For Res. 1990;3:250–5.

Zhao H, Yang L, Peng Z. Developing genome-wide microsatellite markers of bamboo and their applications on molecular marker assisted taxonomy for accessions in the genus Phyllostachys. Sci Rep. 2015;5:8018. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep08018.

Zheng X, Lin S, Fu H, Wan Y, Ding Y. The Bamboo flowering cycle sheds light on flowering diversity. Front Plant Sci. 2020;11:381. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2020.00381.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Prof.Jiang Tingbo of the State Key Laboratory of Tree Genetics and Breeding, Northeast Forestry University for covering consumables and primer synthesis and screening expenses. It is much appreciated that the Ethiopian National Agricultural Biotechnology Research Institute helped us gain access to the molecular lab through Dr. Dejene Girma. The Ethiopian Environment and Forest Research Institute’s Drs. Wubalem Tadesse, Yigardu Mulatu, and Abeje Eshete are also to be thanked for helping to arrange the expenses used for DNA sample collection.

Funding

Expense for DNA sample collection was provided by The Ethiopian Environment and Forest Research Institute. Expenses for consumables used for primer screening and genotyping as well the primer synthesis were covered by the State Key Laboratory of Tree Genetics and Breeding, Northeast Forestry University, Harbin, China.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MA conceived the research work, collected the DNA samples, and carried out the Primer screening, genotyping and scoring SSR data. MA and OA data analysis. MA wrote the manuscript. DB and TF supervised the research.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Scored SSR raw data.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Adem, M., Abdie, O., Feyissa, T. et al. Genetic diversity assessed in Ethiopian highland bamboo [Oldeania alpina (K. Schum) Stapleton] populations revealed by microsatellite markers. CABI Agric Biosci 5, 20 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43170-024-00222-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43170-024-00222-5