Abstract

Background

Infections in communities and hospitals are mostly caused by Staphylococcus aureus strains. This study aimed to determine the prevalence of five genes (SEA, SEB, SEC, SED and SEE) encoding staphylococcal enterotoxins in S. aureus isolates from various clinical specimens, as well as to assess the relationship of these isolates with antibiotic susceptibility. Traditional PCR was used to detect enterotoxin genes, and the ability of isolates expressing these genes was determined using Q.RT-PCR.

Results

Overall; 61.3% (n = 46) of the samples were positive for S. aureus out of 75 clinical specimens, including urine, abscess, wounds, and nasal swabs. The prevalence of antibiotic resistance showed S. aureus isolates were resistant to Nalidixic acid, Ampicillin and Amoxicillin (100%), Cefuroxime (94%), Ceftriaxone (89%), Ciprofloxacin (87%), Erythromycin and Ceftaxime (85%), Cephalexin and Clarithromycin (83%), Cefaclor (81%), Gentamicin (74%), Ofloxacin (72%), Chloramphenicol(59%), Amoxicillin/Clavulanic acid (54%), while all isolates sensitive to Imipinem (100%). By employing specific PCR, about 39.1% of isolates were harbored enterotoxin genes, enterotoxin A was the most predominant toxin in 32.6% of isolates, enterotoxin B with 4.3% of isolates and enterotoxin A and B were detected jointly in 2.1% of isolates, while enterotoxin C, D and E weren’t detected in any isolate.

Conclusion

This study revealed a high prevalence of S. aureus among clinical specimens. The isolates were also multidrug resistant to several tested antibiotics. Enterotoxin A was the most prevalent gene among isolates. The presence of antibiotic resistance and enterotoxin genes may facilitate the spread of S. aureus strains and pose a potential threat to public health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Staphylococcus aureus is a commensal and opportunistic human pathogen that can be found all over the world [1]. It causes a variety of clinical infections, including impetigo, furunculosis, and abscesses on the skin and soft tissues, as well as systemic infections, including pneumonia, bacteremia, endocarditis, and toxin-mediated diseases [2]. It is one of the most common pathogens linked to nosocomial infections in hospitals [3]. S. aureus cause a large amount of morbidity and mortality in developing countries as opposed to other infectious diseases like malaria, tuberculosis, and HIV infections [4]. The fast expansion of drug resistance as well as prominent virulence factors, surface proteins, metabolites and enzymes have all contributed to S. aureus clinical significance [5]. Large numbers of toxins, including hemolysin (α, β, γ, δ) and leukocidin (PVL, Luk E/D) are the most commonly associated virulence factors with these microorganisms [6]. Other virulence factors that cause enterocolitis, scalded skin syndrome, and toxic shock include heat-stable staphylococcal enterotoxins (SEs), exfoliative toxins (ETA and ETB), the toxin of toxic shock syndrome-1(TSST-1) [7, 8]. S. aureus is a concern not only because of its widespread distribution and pathogenicity but also because of its ability to resist antimicrobials [9]. In addition to drug resistance, monitoring of S. aureus strains and determination of susceptibility patterns are critical [10]. Staphylococcal enterotoxins have been identified as etiologic agents of human food poisoning and as active immunologic superantigens that induce non-specific T cell proliferation [11]. Enterotoxins are emetic toxins linked to a broad family of pyrogenic exotoxins produced by staphylococci and streptococci, they are active in concentrations ranging from nanograms to micrograms and are resistant to heat and low pH, also have proteolytic enzymes allowing them to remain active in the digestive tract after ingestion [7]. There are 23 staphylococcal superantigens that have been described, enterotoxins A to E, G to J, R to T, and staphylococcal enterotoxin-like toxins (SE1) K, Q, U, and X (SElK-SElQ, SE1U-SElX) [12,13,14,15,16,17]. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR), DNA probes, and reverse-transcription RT-PCR were used to detect enterotoxins and their activity in S. aureus strains [18]. So the aim of this research is to use PCR to detect enterotoxins genes in S. aureus, assess their distribution through clinical sources, and quantify their prevalence. Furthermore, we looked for any possible connection between enterotoxin prevalence and expression on the one side and antimicrobial susceptibility on the other.

Methods

Collection of samples

The present descriptive study was carried out over a six-month period, between January and July 2015, the research was approved by the ethics committee of the Botany and Microbiology department- the College of Science (Al-Azhar University, Assiut). A total of 75 clinical specimens were collected under aseptic conditions from patients admitted to Assiut University hospital—Faculty of Medicine, Political hospital, Al-Eman hospital, and El-Shmla hospital in Assiut governorate, Egypt. All clinical specimens collected from diverse infections were received from both genders and all age groups. Urine from the infected urinary tract (n = 29; 38.6%), Pus swabs from an abscess (n = 20; 26.6%), Swabs from septic wounds (n = 15; 20%), and Nasal swabs from cases with respiratory symptoms (n = 11; 14.6%). The samples obtained from patients were transported directly to the laboratory in an icebox within 4 h of collection and were immediately processed according to standard microbiological procedures. The sampling swabs were inoculated into a 5 ml Staphylococcus enrichment broth medium [19], blended briefly as necessary, and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h.

Prevalence and characterization of S. aureus isolates

The bacterial culture was streaked on mannitol salt agar (MSA) (Oxoid, Basingstoke, Hampshire, England), with a loopful of enrichment broth and incubated aerobically at 37 °C for 24 to 48 h. Suspected colonies were picked up, sub-cultured once on MSA and twice on 5% defibrinated sheep blood agar medium (Oxoid, Basingstoke, Hampshire, England). Bacterial colonies showing typical characteristics of S. aureus (i.e., beta-hemolytic on blood agar and colonies with golden yellow pigmentation on MSA) were subjected to subculture on to basic media, Gram stain, and biochemical tests catalase and coagulase. Catalase positive and Gram-positive bacteria appearing in the grape-like cluster was spot inoculated to DNase agar (Oxoid, Basingstoke, Hampshire, England). Inoculated DNase agar plates were incubated at 37 °C overnight and flooded with 1 N HCl (Merk, Darmstadt, Germany). Isolates that hydrolyzed DNA in DNase agar were considered S. aureus. Purified colonies were selected, propagated on nutrient agar slope, and preserved at 4 °C.

Antibiotics susceptibility testing

The disc diffusion method was used to determine the antibiotic susceptibility of S. aureus isolates on Mueller Hinton Agar (Oxoid, Basingstoke, Hampshire, England) [20]. Sixteen antibiotics were tested, Imipinem (IPM:10 μg), Nalidixic acid (NA:30 μg), Cephalexin (CN:30 μg), Chloramphenicol (CM:30 μg), Ofloxacin (OFX:5 μg), Amoxicillin (AMX:25 μg), Amoxicillin/Clavulanic acid(AMC:30 μg), Ampicillin (Amp:10 μg), Cefaclor (CEC:30 μg), Gentamycin (GM:30 μg), Erythromycin (E:15 μg), Ciprofloxacin (CIP:5 μg), Ceftriaxone (CRO:30 μg), Clarithromycin (CLR: 15 μg), Ceftaxime (CTX: 30 μg), Cefuroxime (CXM: 30 μg).

DNA extraction and detection of staphylococcal enterotoxin genes

DNA was extracted using a genomic DNA isolation kit (QIAGEN, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Specific PCR using specific primers was used to detect genes encoding enterotoxin A (SEA), enterotoxin B (SEB), enterotoxin C (SEC), enterotoxin D (SED), and enterotoxin E (SEE) [21,22,23,24,25] (Table 1). PCR reaction was conducted in the final volume 25 µl using 2.5 µl Taq polymerase buffer 10X (Promega, Madison, USA) containing a final concentration of 1 mM MgCl2, 2 µl of 2.5 mM dNTPs, 1 µl DNA (50 ng), 1 µl of 10 pmol/µl each specific primer and 0.2 µl Taq polymerase (5 U/µl). The PCR program started with an initial denaturation of 94 °C for 5 min followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at (50 or 52 °C) for 30 s and extension at 72 °C for 1 min. Additional extension at 72 °C for 10 min was done. Aliquots of amplified products were loaded in 1.5% agarose gel, visualized, and photographed using a gel documentation system (Syngene, USA).

RNA extraction and expression of staphylococcal enterotoxin genes

Total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (QIAGEN, Germany). The first strand of cDNA synthesis was performed in a total reaction volume of 25 µl. The reaction mixture contained 2.5 µl of 5X Reverse Transcriptase buffer with 1 mM MgCl2 (Fermentas, USA), 2.5 µl of 2.5 mM dNTPs, 0.5 µl of oligo dT primer 10 pmol/µl, 1 µl RNA (50 ng), 0.2 µl of 200 U/µl Reverse Transcriptase Enzyme in a final reaction volume up to 25 µl by RNase free water. The reverse transcriptase reaction was performed in a thermal cycler (Eppendorf, Germany) run at 42 °C for 1 h and 72 °C for 10 min.

Quantitative PCR was performed using SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Fermentas, USA). Each reaction was performed in a 25 μl mixture, which contained 1 μl of 10 pmol/μl of each primer, 1 μl of cDNA (50 ng), 12.5 μl of 2X SYBR Green PCR Master and 9.5 μl of nuclease-free water. Samples were spin before loading in the rotor wells and each sample was run in triplicate. The amplification program proceeded at 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 15 s; annealing at 60 °C for 30 s and extension at 72 °C for 30 s, then followed by a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. The reaction was performed using a Rotor-Gene 6000 (QIAGEN, ABI System, USA).

Real-Time Q-PCR data analysis

The relative expression ratio was quantified and calculated accurately. Accordingly, for each biological sample, the difference (Δ) in quantification cycle value (CT) between the target (CT (target) averaged from three technical repeats) and the reference 16S rRNA was used as the reference gene (CT (reference), a fixed CT value was used for all samples). The CT (threshold of the cycle) value of each detected gene was determined by automated threshold analysis on ABI System [26]. The CT value of each target gene was normalized to CT (reference) to obtain ΔCT (target) where

The relative expression quantity of the target gene was indicated with

Sequencing, sequence analysis, and phylogenetic tree construction of highly expression isolates

Amplified products of (16S rRNA gene and specific enterotoxin genes) for high expression isolates were purified according to (Maxim biotech INC, USA) and subjected to DNA sequencing using a forward primer in the sequencing reaction [27]. Sequencing was performed using BigDye® Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and model 3130xl Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The obtained DNA nucleotide sequences were analyzed using NCBI-BLAST (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) for confirming the identity of the obtained sequences. Multiple sequence alignment of our sequences and the other published ones were performed using CLUSTLAW (1.83) [28] and a phylogenetic tree was analyzed and generated using MEGA 4 [29].

Statistical analysis

Correlations between data of antibiotic resistance and prevalence of enterotoxins were statistically analyzed using the Graphpad Instat 3. Fisher’s exact test was used to evaluate these correlations, where P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Isolation and identification of S. aureus isolates

In total, 46 S. aureus isolates were isolated from 75 patient samples (29 urine samples, 20 abscess samples, 15 wound samples, and 11 nasal swabs samples). Suspected colonies turned MSA medium yellow due to mannitol fermentation and were given a clear zone around colonies on blood agar because of β- hemolytic activity of isolates. S. aureus isolates were found most often in abscess swabs (15 isolates from 20 samples; 75%) and then wound swabs (9 isolates from 15 samples; 60%), urine samples (16 isolates from 29 samples; 55.1%), and lastly nasal swabs (6 isolates from 11 samples; 54.5%) (Table 2). Data are presented in Table 3 concluded that S. aureus isolates were positive for catalase, coagulase and, DNase, growth on crystal violet agar were purple, white and yellow colonies, also growth on Baird Parker agar medium were black and shiny with narrow white margins surrounded by clear zone, it also positive for Nitrate reduction, Methyl red test, Voges Prausker test and their ability for hydrolysis of Gelatin and Casein while negative for Indole production and Citrate utilization.

Susceptibility of S. aureus isolates to antibiotics

The disc diffusion method was used to screen all of the bacterial isolates on Muller–Hinton agar for sixteen antibiotics. The results revealed that all isolates were sensitive to imipinem (100%), 46% of isolates sensitive to amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, 41% sensitive to chloramphenicol, 28% sensitive to ofloxacin, 26% sensitive to gentamicin, 19% sensitive to Cefaclor, 17% sensitive to cephalexin and clarithromycin, 15% sensitive to erythromycin and ceftaxime, 13% sensitive to ciprofloxacin, 11% sensitive to ceftriaxone, 6% sensitive to cefuroxime, while current results demonstrated all isolates resistant to nalidixic acid, ampicillin, and amoxicillin (Fig. 1).

PCR amplification of enterotoxin genes

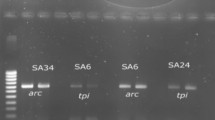

The prevalence of different five enterotoxin genes in S. aureus isolates was investigated using PCR, it was reported that 15 isolates (32.6%) were positive for the SEA gene, 2 isolates (4.3%) were positive for the SEB gene, and only one isolate (2.1%) was positive for both the SEA and SEB genes (Fig. 2), SEC, SED and SEE genes were not found in any of the tested isolates.

The amplified products for SEA gene (A) and SEB gene (B) on 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis which given positive with 16 isolates for SEA with 102 bp and positive with 3 isolates for SEB gene with 478 bp. A Lane M: DNA Ladder 100 bp (Thermo Scientific Fisher. USA), Lane 2 to Lane17: amplified products of 16 isolates for SEA gene. B Lane M: DNA Ladder 100 bp (Thermo Scientific Fisher, USA) lane 2 to Lane 4: amplified products of 3 isolates for SEB gene

Real-time PCR data analysis of S. aureus enterotoxins

The relative gene expression was examined of the tested harbored genes by isolation of RNA from the selected S. aureus isolates and gene expression was verified using a Reverse Transcription Real-time PCR, which enabled comparison of the target and reference genes, where the 16S rRNA was used as the reference gene and the enterotoxin genes as the target genes. The expression of the SEA and SEB genes were expressed to variable degrees in all isolates, it was revealed that isolate no: 10 had the highest SEA gene expression, followed by isolate no: 42 and isolate no: 37, while isolate no: 11 had the highest SEB gene expression, followed by isolate no: 8 and isolate no: 5, (Table 4, Fig. 3). The current report found that MDR of the tested isolates expressed SEA gene with (P value = 0.01) and SEB gene was expressed with (P value = 0.03).

Identification of highly expression isolates and phylogenetic analysis

Completely identification of S. aureus isolates exhibited high level of enterotoxin A and enterotoxin B expression; 16S rRNA gene and enterotoxin genes were amplified and sequenced. The annotated sequences were deposited in GenBank under accession number MF563554 Azhar1 strain for enterotoxin A producing strain and MF563555Azhar2 strain for enterotoxin B producing strain. Sequence alignment and phylogenetic tree analysis revealed that MF563554 given the similarity of about 96% with LT677428 and LT677437 human strains isolated from the head and neck tissue in the USA, while MF563555 had similar of about 90% with HM452073 isolated from bovine mastitis in India (Fig. 4). High expression isolates for SEA and SEB genes using specific primers were amplified and sequenced. The annotated sequence was deposited in GenBank under accession number LC315607 ELBAZ1 for enterotoxin A strain and MF621929 ELBAZ2 for the enterotoxin B strain. Sequence analysis revealed that LC315607 ELBAZ1 strain given 98% similarity with KX777250 which was a local isolate in Egypt while MF621929 ELBAZ2 strain given similar 99% with AB860415 strain isolated from Tokyo food poisoning outbreak and AB716349 isolated from a human nasal swab in Japan. The relationship between ELBAZ1 and ELBAZ2 among other standard strains available in GeneBank were assessed by constructing a neighboring-Joining tree (Figs. 5, 6).

Discussion

S. aureus is a widespread human pathogen that can be found in both hospitals and the public, it's an opportunistic pathogen that can cause several diseases in humans, both self-limiting and life-threatening [30, 31]. In the current investigation revealed high frequency of S. aureus in (61.3%) of isolates. This is higher isolation rate than seen in earlier research (28.1% and 24.5%, respectively) [31, 32]. The higher isolation of S. aureus was observed especially in children and neonates and this finding consistent with report [31], it is believed that their immunity is not properly developed at this phase to cope with bacterial illness hence they are vulnerable and easily infected especially when hospitalized. The older children have also been observed to be more active than adults during their interaction with their playmates and while playing for hours, come in contact with various objects. In this process, they become a target to ubiquitous bacteria such as S. aureus. On MSA and blood agar media, purified S. aureus colonies were smooth, circular, convex, entire, and given different pigments: yellow (47.8%), white (47.8%), and lemony yellow (4.3%), the present data supported through other investigations [32,33,34]. S. aureus isolates were found to have the highest occurrence rate in abscess specimens, which is consistent with previous results [32, 33, 35]. In contrast, the highest incidence rate of S. aureus was showed in urine specimens [36], wounds infections [37, 38] and nasal swabs specimens [39, 40]. The high occurrence of S. aureus was found in abscess specimens which could be attributed to poor personal hygiene and abscess exposure, making it more susceptible to contamination and infection. In addition, some people in the study region treat their abscesses with self-medication or by employment unqualified or poorly trained quacks before seeking proper medical attention, which might account for the level of settlement by S. aureus. Regarding antibiotic resistance, the current results were explained, all S. aureus isolates were resistant to ampicillin, amoxicillin, and nalidixic acid, these findings are consistent with those published in other studies [41, 42]; this suggests that these antibiotics are no longer successful against infections caused by S. aureus. The other studied antibiotics showed a wide range of resistance like Cefuroxime (94%), Ceftriaxone (89%), Ciprofloxacin (87%), Ceftaxime and Erythromycin (85%), Cephalexin and Clarithromycin (83%), Cefaclor (81%), Gentamicin (74%), Ofloxacin (72%), Chloramphenicol (59%). and Amoxicillin/Clavulanic acid (54%), these data were compatible with some reports [32, 43, 44]. The present data were revealed significantly higher resistance to the tested antibiotics than other studies [33, 34, 45]. As a result of the high prevalence of antibiotic resistance in strains, antibiotics commonly used to treat S. aureus infections may not be sufficient. So, physicians must take into account the care guidelines for MRSA infections. All isolates, on the other hand, were found to be susceptible to Imipinem; this finding was consistent with prior investigations [46, 47] that found 87% and 98% of isolates to be susceptible to Imipinem, respectively. So this medication is still successful and can be used as an additional treatment choice for S. aureus infections in the study area. It's possible that the great prevalence of resistance to the antibiotics mentioned is attributable to their widespread usage in the treatment of human diseases. This suggests that these antibiotics are no longer effective as an empirical treatment for S. aureus infections in the research field. The low activity of these antibiotics could be related to earlier exposure to these drugs that would have accelerated the development of resistance. The rise in antibiotic abuse in our region, which stems from self-medication, failure to react to care, and antibiotic-sale actions, can bolster this assertion.

A long history of effective SE determination in epidemiology is cited in both clinical and environmental settings [48]. Enterotoxin genes were discovered in 39.1% of the isolates. Some investigations [49,50,51] found lower levels of toxigenicity (36%; 43%, and 23%, respectively). However, several studies revealed greater levels of enterotoxigenicity (88%, 76.4%, and 93.5%, respectively) [46, 52, 53]. Only two distinct enterotoxin genes were revealed among five enterotoxin genes, which was consistent with the findings of a previous investigation [50]. The enterotoxin A gene was found in 32.6% of isolates, which was similar to other studies [51, 54,55,56] that showed roughly similar levels of enterotoxin A (41%, 42.9%, 44%, and 40%, respectively). Previous studies [46, 57, 58] reported a greater frequency of the SEA gene (66%, 65.2%, and 60.6%, respectively). In contrast, other reported data [59,60,61] found lower prevalence rates of the SEA gene (15%, 18.8%, and 17%). Enterotoxin B was discovered in 4.3% of testing isolates, which was corroborated by investigations [47, 60,61,62], which indicated that (2%, 5%, 5.1%, and 5%, respectively) of isolates carried the SEB gene. According to several investigations, the detection rate of the SEB gene was 44.3%, 38%, and 19.6%, respectively [6, 46, 51]. The SEB gene was found in 21.6% of bovine mastitis cases [63] and 24% of cutaneous infections [64]. SEA and SEB genes were discovered together in only one isolate (2.1%), which is lower than studies [46, 65], which detected SEA and SEB genes combined in 11% and 22% of isolates, respectively. SEC, SED, and SEE genes were not found in any of the examined isolates; nevertheless, additional findings revealed the existence of the SEC, SED, and SEE genes in isolates [46, 51, 56, 66].

It is well recognized that the presence of toxin genes does not imply the potential to produce toxin [46, 67]. As a result, we used the real-time PCR technique to demonstrate the ability of chosen isolates to express the examined enterotoxin genes. With 100% and 80.66%, respectively, two isolates (10 and 42) showed extraordinarily high levels of expression. Furthermore, the SEB gene expression levels were demonstrated in varied degrees in isolates (5, 8, and 11) with a percentage ranging from 66 to 100%. These findings revealed considerable heterogeneity in the expression of enterotoxins among isolates, which was consistent with prior findings [46]. The discrepancies in the prevalence of enterotoxin encoding genes between studies can be due to a variety of factors, including the origin of the isolates, research locations, hygiene restrictions in different countries, and assay methods. The correlation between enterotoxin and resistance to antibiotics is unknown, but the current study demonstrated a strong connection between the determined toxin pattern distribution and antibiotic resistance and that was statically significant with (P value = 0.01 and > 0.05) for SEA and SEB genes respectively, and this was consistent with prior investigations where more association between level of enterotoxins and resistance to antibiotics [46, 68, 69], although some studies suggested a negative correlation between antibiotic resistance and enterotoxin investigation [70, 71]. Also, one of the most important findings in the current investigation was the pigmentation of isolates; although, the relationship between pigment creation on MSA and enterotoxigencity remains unclear; however, there was a putative link between isolate pigmentation and enterotoxin generation. These findings corroborated those investigations that noticed that SEs genes were more correlated with antibiotic resistance and pigment development [69, 70].

Conclusion

The current research looks at the prevalence of enterotoxin genes in clinical samples, especially the SEA gene, which is followed by the SEB gene. The source of isolation was not related to the enterotoxin genes. On the other hand, the SEA gene was discovered to be closely linked to clinical isolates. The existence of toxin genes does not necessarily mean that the toxin can be produced. Our results suggest that assessing S. aureus potential to cause serious disease requires evaluating the degree of expression of certain toxins at mRNA level. Despite the fact that the genetic relationship between resistance and enterotoxins is poorly understood, evidence from our study indicates that enterotoxin and antibiotic resistance are linked in a significant way.

Abbreviations

- S. aureus :

-

Staphylococcus aureus

- SEs:

-

Staphylococcal enterotoxins

- SEA:

-

Staphylococcal enterotoxin A

- SEB:

-

Staphylococcal enterotoxin B

- SEC:

-

Staphylococcal enterotoxin C

- SED:

-

Staphylococcal enterotoxin D

- SEE:

-

Staphylococcal enterotoxin E

- MSA:

-

Mannitol salt agar

- CT:

-

Threshold of a cycle

- Q.RT-PCR:

-

Quantitative Real Time-PCR

References

Reddy PN, Srirama K, Dirisala VR (2017) An update on clinical burden, diagnostic tools, and therapeutic options of Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Dis Res Treat. https://doi.org/10.1177/1179916117703999

Marques SA, Abbade LPF (2020) Severe bacterial skin infections. An Bras Dermatol 95:407–417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abd.2020.04.003

Stryjewski M, Chambers HF (2008) Skin and soft-tissue infections caused by community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Clin Infect Dis 46(5):S368–S377. https://doi.org/10.1086/533593

Nickerson EK, West TE, Day NP, Peacock SJ (2009) Staphylococcus aureus disease and drug resistance in resource-limited countries in south and east Asia. Lancet Infect Dis 9:130–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70022-2

Guo Y, Song G, Sun M, Wang J, Wang Y (2020) Prevalence and therapies of antibiotic-resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 10:107. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2020.00107

Sina H, Ahoyo TA, Moussaoui W, Keller D, Bankolé HS, Barogui Y, Baba-Moussa L (2013) Variability of antibiotic susceptibility and toxin production of Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from skin, soft tissue, and bone related infections. BMC Microbiol 13(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2180-13-188

Larkin EA, Carman RJ, Krakauer T, Stiles BG (2009) Staphylococcus aureus: the toxic presence of a pathogen extraordinaire. Curr Med Chem 16(30):4003–4019. https://doi.org/10.2174/092986709789352321

Pereira V, Lopes C, Castro A, Silva J, Gibbs P, Teixeira P (2009) Characterization for enterotoxin production, virulence factors, and antibiotic susceptibility of Staphylococcus aureus isolates from various foods in Portugal. Food Microbiol 26(3):278–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fm.2008.12.008

Baba-Moussa L, Ahissou H, Azokpota P, Assogba B, Atindéhou MM, Anagonou S, Prévost G (2010) Toxins and adhesion factors associated with Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from diarrhoeal patients in Benin. Afr J Biotechnol. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJB09.1221

Lee AS, de Lencastre H, Garau J, Kluytmans J, Malhotra-Kumar S, Peschel A, Harbarth S (2018) Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Nat Rev Dis Primers 4(1):1–23. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2018.33

Ortega E, Abriouel H, Lucas R, Gálvez A (2010) Multiple roles of Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxins: pathogenicity, superantigenic activity, and correlation to antibiotic resistance. Toxins 2(8):2117–2131. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins2082117

Proft T, Fraser JD (2003) Bacterial superantigens. Clin Exp Immunol 133(3):299–306. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2249.2003.02203.x

Lina G, Bohach GA, Nair SP, Hiramatsu K, Jouvin-Marche E, Mariuzza R (2004) Standard nomenclature for the superantigens expressed by Staphylococcus. J Infect Dis 189(12):2334–2336. https://doi.org/10.1086/420852

Holtfreter S, Broker BM (2005) Staphylococcal superantigens: do they play a role in sepsis. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz) 53(1):13–27 (PMID: 15761373)

Thomas D, Chou S, Dauwalder O, Lina G (2007) Diversity in Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxins. Superantigens Superallergens 93:24–41. https://doi.org/10.1159/000100856

Ono HK, Omoe K, Imanishi KI, Iwakabe Y, Hu DL, Kato H, Shinagawa K (2008) Identification and characterization of two novel staphylococcal enterotoxins, types S and T. Infect Immun 76(11):4999–5005. https://doi.org/10.1128/IAI.00045-08

Wilson GJ, Seo KS, Cartwright RA, Connelley T, Chuang-Smith ON, Merriman JA, Fitzgerald JR (2011) A novel core genome-encoded superantigen contributes to lethality of community-associated MRSA necrotizing pneumonia. PLoS Pathog 7(10):e1002271. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1002271

Chiang YC, Liao WW, Fan CM, Pai WY, Chiou CS, Tsen HY (2008) PCR detection of Staphylococcal enterotoxins (SEs) N, O, P, Q, R, U, and survey of SE types in Staphylococcus aureus isolates from food-poisoning cases in Taiwan. Int J Food Microbiol 121(1):66–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2007.10.005

Mernelius S, Löfgren S, Lindgren PE, Matussek A (2013) The role of broth enrichment in Staphylococcus aureus cultivation and transmission from the throat to newborn infants: results from the Swedish hygiene intervention and transmission of S. aureus study. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 32(12):1593–1598. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-013-1917-6

Wayne, P. A. (2014). Clinical and laboratory standards institute. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. 34(1).

Marsha J, Betley MJ (1988) Nucleotide sequence of the Type A staphylococcal enterotoxin. Gene J Bacteriol 170(1):34–41. https://doi.org/10.1128/jb.170.1.34-41.1988

Jones CL, Khan SA (1986) Nucleotide sequence of the enterotoxin B gene from Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol 166(1):29–33. https://doi.org/10.1128/jb.166.1.29-33.1986

Bohach GA, Schlievert PM (1987) Nucleotide sequence of the staphylococcal enterotoxin C1 gene and relatedness to other pyrogenic toxins. Mol Gen Genet MGG 209(1):15–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00329830

Bayles KW, Iandolo JJ (1989) Genetic and molecular analyses of the gene encoding staphylococcal enterotoxin D. J Bacteriol 171(9):4799–4806. https://doi.org/10.1128/jb.171.9.4799-4806.1989

Couch JL, Soltis MT, Betley MJ (1988) Cloning and nucleotide sequence of the type E staphylococcal enterotoxin gene. J Bacteriol 170(7):2954–2960. https://doi.org/10.1128/jb.170.7.2954-2960.1988

Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD (2001) Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 25(4):402–408. https://doi.org/10.1006/meth.2001.1262

Turner S, Pryer KM, Miao VP, Palmer JD (1999) Investigating deep phylogenetic relationships among cyanobacteria and plastids by small subunit rRNA sequence analysis 1. J Eukaryot Microbiol 46(4):327–338. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1550-7408.1999.tb04612.x

Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ (1994) CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res 22(22):4673–4680. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/22.22.4673

Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S (2007) MEGA4: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol Biol Evol 24(8):1596–1599. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msm092

Landry ML, Garner R, Ferguson D (2003) Comparison of the NucliSens Basic kit (Nucleic Acid Sequence-Based Amplification) and the Argene Biosoft Enterovirus Consensus Reverse Transcription-PCR assays for rapid detection of enterovirus RNA in clinical specimens. J Clin Microbiol 41(11):5006–5010. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.41.11.5006-5010.2003

Eftekhar F, Rezaee R, Azad M, Azimi H, Goudarzi H, Goudarzi M (2017) Distribution of adhesion and toxin genes in staphylococcus aureus strains recovered from hospitalized patients admitted to the ICU. Arch Pediatr Infect Dis. https://doi.org/10.5812/pedinfect.39349

Nsofor CA, Nwokenkwo VN, Ohale CU (2016) Prevalence and antibiotic susceptibility pattern of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from various clinical specimens in south-East Nigeria. MOJ Cell Sci Rep 3(2):1–5. https://doi.org/10.15406/mojcsr.2016.03.00054

Rai S, Yadav UN, Pant ND, Yakha JK, Tripathi PP, Poudel A, Lekhak B (2017) Bacteriological profile and antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of bacteria isolated from pus/wound swab samples from children attending a tertiary care hospital in Kathmandu Nepal. International journal of microbiology. 1:20

Jaran AS (2017) Antimicrobial resistance patterns and plasmid profiles of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from different clinical specimens in Saudi Arabia. Eur Sci J 13(8):1857–7881. https://doi.org/10.19044/esj.2017.v13n9p1

Onanuga A, Awhowho GO (2012) Antimicrobial resistance of Staphylococcus aureus strains from patients with urinary tract infections in Yenagoa, Nigeria. J Pharm Bioallied Sci 4(3):226. https://doi.org/10.4103/0975-7406.99058

Chigbu CO, Ezeronye OU (2003) Antibiotic resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Abia state of Nigeria. Afr J Biotech 2(10):374–378. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJB2003.000-1077

Obiazi HAK, Ekundayo AO (2007) Prevalence and antibiotic susceptibility pattern of Staphylococcus aureus from clinical isolates grown at 37 and 44oC from Irrua, Nigeria. Afr J Microbiol Res 1(5):57–60. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJMR.9000570

Nwoire A, Madubuko E, Eze U, Oti-Wilberforce R, Azi S, Ibiam G, Obi IA (2013) Incidence of staphylococcus aureus in clinical specimens in Federal Teaching Hospital, Abakaliki, Ebonyi State. Merit Res J Med Med Sci 1(3):043–046

Alhashimi HMM, Ahmed MM, Mustafa JM (2017) Nasal carriage of enterotoxigenic Staphylococcus aureus among food handlers in Kerbala city. Karbala Int J Mod Sci 3(2):69–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kijoms.2017.02.003

Said MB, Abbassi MS, Gómez P, Ruiz-Ripa L, Sghaier S, El Fekih O, Torres C (2017) Genetic characterization of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from nasal samples of healthy ewes in Tunisia. High prevalence of CC130 and CC522 lineages. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis 51:37–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cimid.2017.03.002

Denton M, O’Connell B, Bernard P, Jarlier V, Williams Z, Henriksen AS (2008) The EPISA study: antimicrobial susceptibility of Staphylococcus aureus causing primary or secondary skin and soft tissue infections in the community in France, the UK and Ireland. J Antimicrob Chemother 61(3):586–588. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkm531

Elazhari M, Saile R, Dersi N, Timinouni M, Elmalki A, Zriouil SB, Zerouali K (2009) Activité de 16 Antibiotiques vis-à-vis des Staphylococcus aureus communautaires à Casablanca (Maroc) et Prévalence des Souches Résistantes à la Méthicilline. Eur J Sci Res 30:128–137

Tiwari HK, Sapkota D, Sen MR (2008) High prevalence of multidrug-resistant MRSA in a tertiary care hospital of northern India. Infect Drug Resist 1:57. https://doi.org/10.2147/IDR.S4105

Nsofor CA, Ohale CU, Nnamchi CI (2015) Distribution and antibiotics susceptibility pattern of Staphylococcus aureus isolates from health care workers in Owerri, Nigeria. Scholar J Biol Sci 4(4):29–32

Ebrahim-Saraie HS, Heidari H, Khashei R, Edalati F, Malekzadegan Y, Motamedifar M (2017) Trends of antibiotic resistance in Staphylococcus aureus isolates obtained from clinical specimens. J Krishna Inst Med Sci (JKIMSU) 6(3):19–30

Mohammed EY, Abdel-Rhman SH, Barwa R, El-Sokkary MA (2016) Studies on enterotoxins and antimicrobial resistance in Staphylococcus aureus isolated from various sources. Adv Microbiol 6(4):263. https://doi.org/10.4236/aim.2016.64026

Asadollahi P, Delpisheh A, Maleki MH, Jalilian FA, Alikhani MY, Asadollahi K, Taherikalani M (2014) Enterotoxin and exfoliative toxin genes among methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates recovered from Ilam, Iran. Avicenna J Clin Microbiol Infect. https://doi.org/10.17795/ajcmi-20208

Tkáčiková Ľ, Tesfaye A, Mikula I (2003) Detection of the Genes for Staphylococcus aureus Enterotoxins by PCR. Acta Vet Brno 72(4):627–630. https://doi.org/10.2754/avb200372040627

Becker K, Friedrich AW, Lubritz G, Weilert M, Peters G, Von Eiff C (2003) Prevalence of genes encoding pyrogenic toxin superantigens and exfoliative toxins among strains of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from blood and nasal specimens. J Clin Microbiol 41(4):1434–1439. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.41.4.1434-1439.2003

Naffa RG, Bdour SM, Migdadi HM, Shehabi AA (2006) Enterotoxicity and genetic variation among clinical Staphylococcus aureus isolates in Jordan. J Med Microbiol 55(2):183–187. https://doi.org/10.1099/jmm.0.46183-0

Sabouni F, Mahmoudi S, Bahador A, Pourakbari B, Sadeghi RH, Ashtiani MTH, Mamishi S (2014) Virulence factors of Staphylococcus aureus isolates in an Iranian referral children’s hospital. Osong Public Health Res Perspect 5(2):96–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phrp.2014.03.002

Elazhari M, Elhabchi D, Zerouali K, Dersi N, Elmalki A, Hassar M, Timinouni M (2011) Prevalence and distribution of Superantigen toxin genes in clinical community isolates of Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol Parasitol 2:107. https://doi.org/10.4172/2155-9597.1000107

Cao H, Wang M, Zheng R, Li X, Wang F, Jiang Y, Yang Y (2012) Investigation of enterotoxin gene in clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus. J Southern Med Univ 32(5):738–741

Adwan GM, Abu-Shanab BA, Adwan KM, Jarrar NR (2006) Toxigenicity of Staphylococcus aureus isolates from Northern Palestine. Emirates Med J 24(2):127–129

Xie Y, He Y, Gehring A, Hu Y, Li Q, Tu SI, Shi X (2011) Genotypes and toxin gene profiles of Staphylococcus aureus clinical isolates from China. PLoS ONE 6(12):e28276. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0028276

Yaslianifard S, Mirzaii MSM, Kermanian FF, Marashi SMA, Dehaghi NK, Alimorad S, Yaslianifard S (2017) Virulence genes in Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from different clinical specimens in an Iranian hospital. EC Microbiol 5:86–92. https://doi.org/10.5812/ircmj.15722

Bhatty M, Ray P, Singh R, Jain S, Sharma M (2013) Presence of virulence determinants amongst Staphylococcus aureus isolates from nasal colonization, superficial & invasive infections. Indian J Med Res 138(1):143

Kamarehei F, Ghaemi EA, Dadgar T (2013) Prevalence of enterotoxin A and B genes in Staphylococcus aureus isolated from clinical samples and healthy carriers in Gorgan City, North of Iran. Indian J Pathol Microbiol 56(3):265. https://doi.org/10.4103/0377-4929.120388

Tokajian S, Haddad D, Andraos R, Hashwa F, Araj G (2011) Toxins and antibiotic resistance in Staphylococcus aureus isolated from a major hospital in Lebanon. Int Scholar Res Not. https://doi.org/10.5402/2011/812049

Wang LX, Hu ZD, Hu YM, Tian B, Li J, Wang FX, Li J (2013) Molecular analysis and frequency of Staphylococcus aureus virulence genes isolated from bloodstream infections in a teaching hospital in Tianjin. China Genet Mol Res 12(1):646–654. https://doi.org/10.4238/2013.March.11.12

Sirehvand M, Zareh KS, Honarmand JS (2015) The prevalence of ses genes of staphylococcus aureus isolated from patients in ahwaz hospitals by multiplex pcr. 528–536. https://www.sid.ir/en/journal/ViewPaper.aspx?id=521759

Ataee RA, Karami A, Izadi M, Aghania A, Ataee MH (2011) Molecular screening of staphylococcal enterotoxin B gene in clinical isolates. Cell Journal (Yakhteh) 13(3):187–192

Al-Jumaily EF, Saeed NM, Hussain H, Khanaka HH (2014) Detection of enterotoxin types produce by coagulase positive Staphylococcus species isolated from mastitis in dairy cows in Sulaimaniyah region. Appl Sci Rep 2(1):19–26. https://doi.org/10.15192/PSCP.ASR.2014.2.1.1926

Fooladi AI, Tavakoli HR, Naderi A (2010) Detection of enterotoxigenic Staphylococcus aureus isolates in domestic dairy products. Iran J Microbiol 2(3):137

Jassim HA, Bakir SS, Alhamdi KI, Albadran AE (2013) Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for detection superantigenicity of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from psoriatic patients. Int J Microbiol Res Rev 1(1):022–027

Anvari SH, Sattari M, Forozandehe MM, Najar PS (2008) Detection of Staphylococcus aureus Enterotoxins A to E from clinical samples by PCR. 826–829. PMID: 22347562

Peters IR, Helps CR, Hall EJ, Day MJ (2004) Real-time RT-PCR: considerations for efficient and sensitive assay design. J Immunol Methods 286(1–2):203–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jim.2004.01.003

Pourmand MR, Memariani M, Hoseini M, Yazdchi SB (2009) High prevalence of sea gene among clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus in Tehran. Acta Med Iran 47(5):357–361

Indrawattana N, Sungkhachat O, Sookrung N, Chongsa-Nguan M, Tungtrongchitr A, Voravuthikunchai SP, Chaicumpa W (2013) Staphylococcus aureus clinical isolates: antibiotic susceptibility, molecular characteristics, and ability to form biofilm. Biomed Res Int. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/314654

Jiménez JN, Ocampo AM, Vanegas JM, Rodríguez EA, Garcés CG, Patiño LA, Correa MM (2011) Characterisation of virulence genes in methicillin susceptible and resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates from a paediatric population in a university hospital of Medellin, Colombia. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 106:980–985. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0074-02762011000800013

Sapri HF, Sani NAM, Neoh HM, Hussin S (2013) Epidemiological study on Staphylococcus aureus isolates reveals inverse relationship between antibiotic resistance and virulence repertoire. Indian J Microbiol 53(3):321. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12088-013-0357-4

Acknowledgements

All appreciation for workers in Plant Protection and Biomolecular Diagnosis Department, City of Scientific Research and Biotechnological Applications, Alexandria, Egypt, for their assistance during the study.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AB, EB, UA and AA study concept and design, development of the study, data interpretation and manuscript revision and drafting; AB, EB and UA contributed to sample collection, phenotypic studies; AB and AA contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools and molecular studies. All the authors have read and approved of the final version of the manuscript for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee, Botany and Microbiology department- the College of Science (Al-Azhar University, Assiut) obtained the approval of the Ethics Committees and the research was conducted following the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki but Ethical approval number: not available. All specimens were collected aseptically and transported to the microbiology laboratory, where they were immediately processed according to the standard microbiological procedures. We would like to confirm that this material is the authors’ own original work, which has not been previously published elsewhere. The paper is not currently being considered for publication elsewhere. The paper reflects the authors’ own research and analysis in a truthful and complete manner. The paper properly credits the meaningful contributions of co-authors and co researchers. The results are appropriately placed in the context of prior and existing research. All authors have been personally and actively involved in substantive work leading to the manuscript and will hold themselves jointly and individually responsible for its content.

Consent for publication

“Not applicable”.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Baz, A.A., Bakhiet, E.K., Abdul-Raouf, U. et al. Prevalence of enterotoxin genes (SEA to SEE) and antibacterial resistant pattern of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from clinical specimens in Assiut city of Egypt. Egypt J Med Hum Genet 22, 84 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43042-021-00199-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43042-021-00199-0