Abstract

Background

Bochdalek hernia in an adult is very rare and often needs an immediate surgical repair for the herniation. Although its etiology and surgical techniques have frequently been reported, perioperative complications, especially cardiopulmonary problems, remain unknown. We reported two adults with Bochdalek hernia and reviewed the published literatures with a focus on these issues.

Case presentation

We experienced two adult cases of Bochdalek hernia with gastrointestinal strangulation. One case had massive herniation of the stomach, colon, spleen, and pancreas in the left chest, causing repeated vomiting. The other had a right-side hernia with strangulation of the colon. We successfully performed emergency repairs of these diaphragmatic hernias without any postoperative complications.

Conclusions

Our literature review revealed that life-threatening cardiopulmonary complications, such as empyema or cardiac arrest caused by the tamponade effect of the herniated viscera, sometimes occurred in patients with Bochdalek hernia. These complications were found in Bochdalek hernia with gastrointestinal strangulation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Bochdalek hernia is a congenital diaphragmatic defect caused by a failure in posterolateral diaphragmatic formation and is associated with severe pulmonary complications during perinatal life. However, some patients with this hernia are asymptomatic and exhibit respiratory and/or abdominal symptoms caused by the herniation of abdominal viscera for the first time in adulthood [1,2,3].

In the last decade, there have been more than 50 cases of Bochdalek hernia in adults [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57]. Surgical approaches have varied between institutions: laparoscopy or thoracoscopy as well as primary closure or mesh repair. Although most cases had a favorable postoperative course, some developed severe cardiopulmonary complications and these risk factors remain unclear.

We encountered two adult cases of Bochdalek hernia. One case had massive herniation of the stomach, colon, spleen, and pancreas in the left chest with gastrointestinal obstructive symptoms, and the other had a right-side hernia with strangulation of the colon. We herein described these cases and reviewed previous case reports, particularly those with a focus on respiratory complications.

Case presentation

Case 1

A 43-year-old healthy male was admitted with abdominal pain and vomiting for 3 days. He had a previous history of a hemorrhagic gastric ulcer 10 years before and no trauma. X-ray and computed tomography (CT) revealed a left diaphragmatic hernia (Fig. 1a, b). CT showed that the entire stomach, spleen, pancreatic tail, and splenic flexure occupied two thirds of the left thoracic cavity. Upside-down stomach and gastric volvulus causing vomiting were detected. The patient was diagnosed with Bochdalek hernia based on the presence of a hernia orifice in the posterolateral aspect of the left diaphragm. When CT imaging performed 10 years before was retrospectively reviewed, a more modest degree of Bochdalek hernia was detected, which may have caused the gastric ulcer at that time (Fig. 2).

A nasogastric tube was inserted to decompress the stomach; however, the patient had persistent abdominal pain and incarcerated obstruction. He was referred to our hospital for a surgical intervention. The results of laboratory examinations were within normal ranges, and the respiratory function test showed a percentage of vital capacity of 93.9% and forced expiratory volume in 1 s of 106.2%. We preoperatively discussed with an anesthesiologist about perioperative administration of neutrophil elastase inhibitor or steroids for re-expansion pulmonary edema which we have expected to occur after restoring herniated viscera.

The patient underwent L-shaped laparotomy to surgically repair Bochdalek hernia. A 7-cm hernia orifice was observed in the left posterior diaphragm (Fig. 3). Herniated viscera were carefully returned back into the abdominal cavity, and a hernia sac was not detected. There were no adhesions between abdominal viscera and the thoracic cavity or left lung. The left diaphragmatic defect was repaired by primary closure with 0 absorbable thread without diaphragmatic tension. Chest X-ray immediately after surgery showed a fully expanded left lung and that 5 h after surgery showed no pleural effusion or re-expansion pulmonary edema (Fig. 4).

The postoperative course was uneventful, and diaphragmatic hernia has not recurred for 3 months.

Case 2

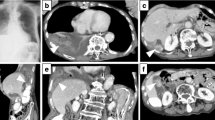

The patient was an 87-year-old female with a previous history of an asymptomatic diaphragmatic hernia. She was transferred to our hospital with sudden abdominal pain and vomiting. X-ray and CT imaging showed a right diaphragmatic hernia with a dilated transverse colon and modest ascites (Fig. 5a, b). Since the hernia orifice was located in the posterolateral aspect of the right diaphragm, she was diagnosed with Bochdalek hernia with incarceration of the transverse colon. The results of laboratory examinations and arterial blood gas measurements were within normal ranges, with the exception of a modest oxygen level (50.6 mmHg).

She underwent emergency reverse L-shaped laparotomy for strangulated Bochdalek hernia. A 4-cm hernia orifice was observed in the right posterior diaphragm. The right transverse colon was incarcerated into the right chest cavity, and the prolapsed colon was returned to the abdominal cavity. A hernia sac was detected as well as adhesions between the prolapsed colon and hernia sac. The hernia orifice was repaired by a primary suture with 0 absorbable thread. The necrotic colon was excised by right hemicolectomy, and a thoracostomy tube was inserted into the right chest. She recovered without any complications, and there was no recurrence in the month following surgery.

Discussion

Bochdalek hernia is a well-known congenital diaphragmatic disease due to life-threatening lung hypoplasia and pulmonary hypertension during perinatal life. It is caused by a diaphragmatic malformation in the posterolateral side. However, some cases of Bochdalek hernia remain asymptomatic until adulthood [1,2,3]. Previous reviews described Bochdalek hernia in adults, with the most common symptoms at presentation being chest and/or abdominal pain (66%) and symptoms of ileus (38%) [3]. Surgical repair for herniation by transthoracic or transabdominal approaches is recommended for symptomatic patients with prolapsed viscera. Although the etiology of Bochdalek hernia and surgical techniques have frequently been reported, perioperative cardiopulmonary pitfalls remain unknown.

Between 2010 and 2018, 55 operated case reports were obtained in PubMed/Medline with the keywords of “Bochdalek hernia” and “adult” [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57]. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of these reports and the present cases. The mean age of patients was 41 years, and left-side Bochdalek hernia was more common (n = 36, 65%). The majority of patients presented with chest and/or abdominal symptoms (n = 53, 96%), such as pain and dyspnea. A hernia sac was absent in 62% (present in 13 patients). Surgical approaches were as follows: thoracoscopy (n = 2), thoracostomy (n = 8), laparoscopy (n = 19), and laparotomy (n = 26).

In terms of preoperative cardiopulmonary problems, 3 patients were initially misdiagnosed with pneumothorax with air in the chest cavity on imaging tests [4, 32, 40]. A severely dilated stomach or colon in the chest mimicked a pneumothorax on chest X-rays, and 2 patients underwent thoracic drainage. Seventeen cases (31%) showed a mediastinal shift toward the opposite side on X-rays, and cardiac arrest occurred in one case, which may have been caused by the tamponade effect of the hugely dilated intrathoracic stomach [24]. Another patient with preoperative cardiac arrest caused by the hemorrhagic shock had herniation of the stomach and spleen [14]. The entire stomach was necrotic, and there was a large amount of bleeding from the spleen.

Intraoperatively, adhesions between the herniated viscera and a sac or the lungs were often observed (n = 6, 11%), and adhesiolysis was safely performed by both abdominal and thoracic approaches [8, 20, 21, 34, 55, 57]. Gastrointestinal strangulation was detected (stomach: n = 7; small intestine: n = 6; colon: n = 2), and their perforation frequently occurred (n = 5).

Postoperatively, some patients needed respiratory support, including mechanical ventilation or pleural effusion puncture (n = 7) [10, 11, 32, 37, 43, 50, 53]. The most severe respiratory complication was empyema (n = 4), which led to the death of one patient [8, 39, 42, 54]. Although most patients with Bochdalek hernia had an uneventful postoperative course, empyema occurred in patients with ischemic or necrotic changes in the herniated abdominal viscera (Table 1). A thoracostomy tube may need to be intraoperatively inserted in patients with gastrointestinal necrosis for prevention of these respiratory complications.

We had concerns about intra- and postoperative re-expansion pulmonary edema after reducing the herniation, which is often observed after thoracic drainage for a pneumothorax. And we were perioperatively ready to administer neutrophil elastase inhibitor or steroids for re-expansion pulmonary edema. However, it did not occur in either patient during their postoperative courses. To the best of our knowledge, there has been no report on re-expansion pulmonary edema after surgery for Bochdalek hernia. One of the possible explanations for this is that the lungs of patients with Bochdalek hernia are often hypoplastic and postoperative overexpansion of the remnant lung may fill in the gaps; however, the lungs of patients with a pneumothorax may suddenly collapse and re-expand after drainage.

Conclusions

Bochdalek hernia in adulthood is rare and has an acute course. Severe pulmonary complications are expected to occur especially in patients with gastrointestinal strangulation.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable

Abbreviations

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

References

Bujanda L, Larrucea I, Ramos F, Muñoz C, Sánchez A, Fernández I. Bochdalek’s hernia in adults. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;32:155–7.

Rout S, Foo FJ, Hayden JD, Guthrie A, Smith AM. Right-sided Bochdalek hernia obstructing in an adult: case report and review of the literature. Hernia. 2007;11:359–62.

Brown SR, Horton JD, Trivette E, Hofmann LJ, Johnson JM. Bochdalek hernia in the adult: demographics, presentation, and surgical management. Hernia. 2011;15:23–30.

Arya S, Shahab S, Kumar R, Garg PK. Adult Bochdalek hernia with organo-axial gastric volvulus: misdiagnosed as hydropneumothorax. Acta Medica (Hradec Kralove). 2018;61:108–10.

Kikuchi S, Nishizaki M, Kuroda S, Kagawa S, Fujiwara T. A case of right-sided Bochdalek hernia incidentally diagnosed in a gastric cancer patient. BMC Surg. 2016;16:34.

Shen YG, Jiao NN, Xiong W, Tang Q, Cai QY, Xu G, et al. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery for adult Bochdalek hernia: a case report. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2016;11:165.

Banchini F, Santoni R, Banchini A, Bodini FC, Capelli P. Right posterior diaphragmatic hernia (Bochdalek) with liver involvement and alteration of hepatic outflow in adult: a case report. Springerplus. 2016;5:1561.

Watanabe M, Ishibashi O, Watanabe M, Kondo T, Ohkohchi N. Complicated adult right-sided Bochdalek hernia with Chilaiditi’s syndrome: a case report. Surg Case Rep. 2015;1:95.

Moro K, Kawahara M, Muneoka Y, Sato Y, Kitami C, Makino S, et al. Right-sided Bochdalek hernia in an elderly adult: a case report with a review of surgical management. Surg Case Rep. 2017;3:109.

Ohtsuka Y, Suzuki TH. Right-sided Bochdalek hernia in an elderly patient: a case review of adult Bochdalek hernias from 1982 to 2015 in Japan. Acute Med Surg. 2016;4:209–12.

Sutedja B, Muliani Y. Laparoscopic repair of a Bochdalek hernia in an adult woman. Asian J Endosc Surg. 2015;8:354–6.

Kohli N, Mitreski G, Yap CH, Leong M. Massive symptomatic right-sided Bochdalek hernia in an adult man. BMJ Case Rep. 2016;2016. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2016-217432.

Tonini V, Gozzi G, Cervellera M. Acute pancreatitis due to a Bochdalek hernia in an adult patient. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;2:2018. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2017-223852.

Koca YS, Barut I, Yildiz İ, Yazkan R. The cause of unexpected acute abdomen and intra-abdominal hemorrhage in 24-week pregnant woman: Bochdalek hernia. Case Rep Surg. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/6591714.

Rehman A, Maliyakkal AM, Naushad VA, Allam H, Suliman AM. A lady with severe abdominal pain following a Zumba dance session: a rare presentation of Bochdalek hernia. Cureus. 2018;10:e2427.

Cindolo L, Berardinelli F, Manzi A, Spagnuolo F, Fabbri E, Castellan P, et al. Intraoperative presentation of Bochdalek’s hernia in an adult during robotic-assisted partial nephrectomy: an uncommon situation and literature review. Arch Ital Urol Androl. 2016;87:327–9.

Manipadam JM, Sebastian GM, Ambady V, Hariharan R. Perforated gastric gangrene without pneumothorax in an adult Bochdalek hernia due to volvulus. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10:PD09–10.

Amer K. Thoracoscopic approach to congenital diaphragmatic hernias in adults: Southampton approach and review of the literature. J Vis Surg. 2017;3:176.

Lee JS, Kim ES, Jung MK, Kim SK, Jin S, Lee DH, et al. An unexpected adverse event during colonoscopy screening: Bochdalek hernia. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2018;71:290–3.

Matsudera S, Nakajima M, Takahashi M, Muroi H, Kikuchi M, Shida Y, et al. Laparoscopic surgery for a Bochdalek hernia triggered by pregnancy in an adult woman: a case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2018;48:10–5.

Atef M, Emna T. Bochdalek hernia with gastric volvulus in an adult: common symptoms for an original diagnosis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e2197.

Yagmur Y, Yiğit E, Babur M, Gumuş S. Bochdalek hernia: a rare case report of adult age. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2015;5:72–5.

Ayane GN, Walsh M, Shifa J, Khutsafalo K. Right congenital diaphragmatic hernia associated with abnormality of the liver in adult. Pan Afr Med J. 2017;28:70.

Manson HJ, Goh YM, Goldsmith P, Scott P, Turner P. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia causing cardiac arrest in a 30-year-old woman. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2017;99:e75–7.

Ekanayake E, Fernando SA, Durairajah PL, Jayasundara J. Incarcerated Bochdalek hernia causing bowel obstruction in an adult male patient. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2017;99:e159–61.

Zhou Y, Du H, Che G. Giant congenital diaphragmatic hernia in an adult. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2014;9:31.

Deb SJ. Massive right-sided Bochdalek hernia with two unusual findings: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2011;5:519.

Salústio R, Nabais C, Paredes B, Sousa FV, Porto E, Fradique C. Association of intestinal malrotation and Bochdalek hernia in an adult: a case report. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7:296.

Fatimi SH, Sajjad N, Muzaffar M, Hanif HM. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia presenting in the sixth decade mimicking pneumonia. J Pak Med Assoc. 2011;61:600–1.

Venkatesh SP, Ravi MJ, Thrishuli PB, Sharath Chandra BJ. Asymptomatic presentation of Bochdalek’s hernia in an adult. Indian J Surg. 2011;73:382–3.

John PH, Thanakumar J, Krishnan A. Reduced port laparoscopic repair of Bochdalek hernia in an adult: a first report. J Minim Access Surg. 2012;8:158–60.

Mathai AS, Singh M. Peri-operative course of peritonitis following tube thoracostomy: a misdiagnosed case of congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Anesth Essays Res. 2011;5:92–4.

Ngai I, Sheen JJ, Govindappagari S, Garry DJ. Bochdalek hernia in pregnancy. BMJ Case Rep. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2012-006859.

Husain M, Hajini FF, Ganguly P, Bukhari S. Laparoscopic repair of adult Bochdalek’s hernia. BMJ Case Rep. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2013-009131.

Newman MJ. A mistaken case of tension pneumothorax. BMJ Case Rep. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2013-203435.

Carrascosa MF, Carrera IA, García JA, García MA, Tapia AD, Lavín AC, et al. Symptomatic Bochdalek hernia in an adult patient. BMJ Case Rep. 2010. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr.05.2010.2996.

Islah MA, Jiffre D. A rare case of incarcerated Bochdalek diaphragmatic hernia in a pregnant lady. Med J Malaysia. 2010;65:75–6.

Soylu E, Junnarkar S, Kocher HM. Recurrent indigestion in a young adult. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2010;4:518–23.

Granier V, Coche E, Hantson P, Thoma M. Intrathoracic caecal perforation presenting as dyspnea. Case Rep Med. 2010. https://doi.org/10.1155/2010/296730.

Choi YK, Ahn JH, Kim KC, Won TH. An adult right-sided Bochdalek hernia accompanied with hepatic hypoplasia and inguinal hernia. Korean J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012. https://doi.org/10.5090/kjtcs.2012.45.5.348.

Vega MT, Maldonado RH, Vega GT, Vega AT, Liévano EA, Velázquez PM. Late-onset congenital diaphragmatic hernia: a case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2013;4:952–4.

Suzuki T, Okamoto T, Hanyu K, Suwa K, Ashizuka S, Yanaga K. Repair of Bochdalek hernia in an adult complicated by abdominal compartment syndrome, gastropleural fistula and pleural empyema: report of a case. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2014;5:82–5.

Costa Almeida CE, Reis LS, Almeida CM. Adult right-sided Bochdalek hernia with ileo-cecal appendix: Almeida-Reis hernia. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2013;4:778–81.

Ayiomamitis GD, Stathakis PC, Kouroumpas E, Avraamidou A, Georgiades P. Laparoscopic repair of congenital diaphragmatic hernia complicated with sliding hiatal hernia with reflux in adult. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2012;3:597–600.

Herling A, Makhdom F, Al-Shehri A, Mulder DS. Bochdalek hernia in a symptomatic adult. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;98:701–4.

Somani SK, Gupta P, Tandon S, Sonkar D, Bhatnagar S, Saxena M. Bochdalek diaphragmatic hernia masquerading as tension hydropneumothorax in an adult. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;141:300–1.

Slesser AA, Ribbans H, Blunt D, Stanbridge R, Buchanan GN. A spontaneous adult right-sided Bochdalek hernia containing perforated colon. JRSM Short Rep. 2011;2:54.

Nishihara Y, Kawaguchi Y, Urakami H, Seki S, Ohishi T, Isobe Y, et al. Gastric volvulus with a large bochdalek hernia in an adult successfully treated with emergency endoscopic reduction followed by elective laparoscopic mesh repair: a case study. Asian J Endosc Surg. 2016;9:318–21.

Oguma J, Ozawa S, Kazuno A, Nitta M, Ninomiya Y. Laparoscopic mesh repair of adult diaphragmatic hernia: a report of two cases. Asian J Endosc Surg. 2017;10:179–82.

Chen B, Finnerty BM, Schamberg NJ, Watkins AC, DelPizzo J, Zarnegar R. Transabdominal robotic repair of a congenital right diaphragmatic hernia containing an intrathoracic kidney: a case report. J Robot Surg. 2015;9:357–60.

Jambhekar A, Robinson S, Housman B, Nguyen J, Gu K, Nakhamiyayev V. Robotic repair of a right-sided Bochdalek hernia: a case report and literature review. J Robot Surg. 2018;12:351–5.

Dente M, Bagarani M. Laparoscopic dual mesh repair of a diaphragmatic hernia of Bochdalek in a symptomatic elderly patient. Updates Surg. 2010;62:125–8.

Moser F, Signorini FJ, Maldonado PS, Gorodner V, Sivilat AL, Obeide LR. Laparoscopic repair of giant Bochdalek hernia in adults. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2016;26:911–5.

Wenzel-Smith G. Posterolateral diaphragmatic hernia with small-bowel incarceration in an adult. S Afr J Surg. 2013;51:73–4.

Jha A, Ahmad I, Naseem I. A rare case of partial diaphragmatic agenesis with thoracic liver herniation and anteriorly displaced intrathoracic kidney in an adult diagnosed by displaced diaphragmatic crus. Hernia. 2014;18:893–6.

Debergh I, Fierens K. Laparoscopic repair of a Bochdalek hernia with incarcerated bowel during pregnancy: report of a case. Surg Today. 2014;44:753–6.

Muhammad MI, Abdelrahman AI. A rare presentation of Bochdalek’s hernia containing duodenum and pancreas. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 2012;20:734–6.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Funding

None to declare

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors participated in the operations or postoperative management. All authors designed and drafted the manuscript. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval and consent to publish have been obtained from all participants.

Competing interests

None to declare

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Akita, M., Yamasaki, N., Miyake, T. et al. Bochdalek hernia in an adult: two case reports and a review of perioperative cardiopulmonary complications. surg case rep 6, 72 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-020-00833-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-020-00833-w