Abstract

Background

Bochdalek hernia (BH) is generally congenital, presenting with respiratory distress. However, this pathology is rarely detected in adults. Some adult cases of BH present with symptoms attributed to the hernia, but incidental detection of BH is increasing among asymptomatic adults due to advances in imaging modalities. This report presents the management of incidental BH patients detected in the preoperative period of gastric cancer.

Case presentation

An asymptomatic 76-year-old woman was diagnosed with advanced gastric cancer during follow-up after radiotherapy for uterine cervical cancer. Computed tomography (CT) was performed to exclude metastatic gastric cancer, incidentally detecting right-sided BH. We planned distal gastrectomy with lymph node dissection for gastric cancer and simultaneous repair of BH using a laparoscopic approach. We performed laparoscopic gastrectomy for gastric cancer and investigated the right-sided BH to assess whether repair during surgery was warranted. Herniation of the liver into the right hemithorax was observed, but was followed-up without surgical repair because the right hepatic lobe was adherent to the remnant right anterior hemidiaphragm and covered the huge defect in the right hemidiaphragm. No intra- or postoperative pneumothorax was observed during pneumoperitoneum.

Conclusion

Regardless of symptoms, repair of adult BH is generally recommended to prevent visceral incarceration. However, BH in asymptomatic adults appears to be more common than previously reported in the literature. Surgeons need to consider the management of incidental BH encountered during thoracic or abdominal surgery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Bochdalek hernia (BH) was first described in 1848 as a congenital hernia resulting from developmental failure of the posterolateral diaphragmatic formation to fuse properly [1]. Most BHs are diagnosed in the neonatal period with clinical symptoms caused by pulmonary insufficiency [2–4]. BH identified in adulthood is extremely rare and only around 100 cases of BH in adults have been reported. Moreover, only 35 cases of right-sided BH in adults have been reported [5, 6]. However, the prevalence of BH in adults has been estimated to range between 0.17 and 12.7 % [4, 7, 8]. Incidental identification of BH in asymptomatic adults is increasing due to advances in imaging modalities, and this pathology may be more common than previously reported. Adult BH patients are generally recommended to undergo surgical repair regardless of symptoms, to prevent the incarceration of viscera [9–11].

We report a case of gastric cancer with right-sided BH diagnosed incidentally on preoperative computed tomography (CT).

Case presentation

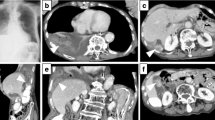

An asymptomatic 76-year-old woman underwent follow-up fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) after radiotherapy for uterine cervical cancer (T4N0M0 Stage IVA) and showed strong FDG accumulation in the stomach. She had no history of trauma. She had hypertension and cholangiectasis of unknown origin. Physical examination revealed nothing of note. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) showed an elevated lesion, 30 mm in diameter, at the lesser curvature in the antrum of the stomach, and biopsy indicated well-differentiated adenocarcinoma. Chest X-ray revealed that the right hemidiaphragm was exceptionally high (Fig. 1a, b). Preoperative CT performed to rule out metastatic disease showed protrusion of the right hepatic lobe into the right hemithorax, and right-sided BH was therefore diagnosed incidentally (Fig. 2a, b). We re-evaluated images from CT performed 5 months earlier for the staging of the cervical cancer, to compare the condition of BH. No differences were apparent in terms of sizes of the defect or herniated liver between preoperative CT for gastric cancer and the CT for staging cervical cancer (Fig. 1a–c). The patient was diagnosed with advanced gastric cancer without lymph nodes or distant metastases (T2N0M0 Stage IB), accompanied by right-sided BH. We planned to perform distal gastrectomy with lymph nodes dissection for gastric cancer and simultaneous repair of the right-sided BH using the laparoscopic approach. Laparoscopic distal gastrectomy with lymph nodes dissection and cholecystectomy was performed under 10 cmH2O pressure of pneumoperitoneum. Intraoperatively, laparoscopic evaluation revealed herniation of the right hepatic lobe into the right hemithorax. However, we did not perform surgical repair of the BH because the right hepatic lobe that had herniated into the thoracic cavity was adherent to the remnant right anterior hemidiaphragm and covered the huge defect in the right hemidiaphragm (Fig. 3a, b). No intra- or postoperative pneumothorax was observed accompanying the pneumoperitoneum. The postoperative course was uneventful and the patient was discharged 14 days postoperatively. On follow-up at 3 months postoperatively, the patient was well and remained asymptomatic.

a, b Findings from preoperative thoracic and abdominal computed tomography (CT) for gastric cancer. Transverse CT shows the right hepatic lobe in the right inferior intrathoracic area (a: asterisk). On coronal section, the asterisk indicates the right hepatic lobe herniating into the right hemithorax via a diaphragmatic defect (b). c Thoracic and abdominal CT before radiotherapy for cervical cancer. The right hepatic lobe has herniated into the right hemithorax (asterisk), and appears no different in terms of the size of herniated liver compared to the preoperative CT for gastric cancer

Discussion

BH is a congenital diaphragmatic anomaly that occurs in one in 2000–12,500 live births, but is extremely rare in adults [10, 12]. This defect is caused by incomplete closure of the pleuroperitoneal folds around the 8th week of gestation. BH is more common on the left side (80–85 %), because complete closure occurs on the right side before the left side and the liver usually barricades against herniation on the right side. Most BHs are diagnosed in the neonatal period after the neonate presents with life-threating acute respiratory distress [11, 13]. In contrast to the acute presentation in neonatal BH, most adult BH patients present with more chronic symptoms, such as chest or abdominal pain, and 14 % of adult BHs are asymptomatic. Only 35 cases of right-sided BH in adults have been reported [5]. Although the true prevalence of adult BH remains unclear, Mullins reported that the incidence of adult BH was 0.17 %, with 68 % being right-sided and 77 % of patients being female, based on a review of 13,138 abdominal CT reports performed to rule out metastatic disease in patients with known malignant disease [7]. Those findings suggest that right-sided BH is more common than previously reported, and that female or right-sided BH may yield clinically silent disease. Although some cases of adult BH might be missed or unreported, incidental findings of adult BH seem likely to increase with the widespread use of advanced imaging modalities such as multi-detector row CT (MDCT) [14].

Chest X-rays may show abnormal contents above the diaphragm, and an air meniscus sign indicates the presence of BH [15]. However, BH may be difficult to appreciate on chest X-ray. In the current case, chest X-ray showed only elevation of the right hemidiaphragm (Fig. 1). CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are the most useful examinations for the diagnosis of BH. These modalities are suitable for detecting fat or soft tissue on the upper surface of the diaphragm and sagittal and coronal reformatted images can show the diaphragmatic defect and hernia contents. Another characteristic of BH is the posterolateral location. These findings were detected in the current case.

Most authors have suggested that BH in adults generally warrants surgical repair regardless of symptoms, given the risk of visceral incarceration [9, 10, 16], with the resulting defects repaired by primary repair or interposition of a mesh graft. Under emergency conditions, laparotomy has been considered the best approach for both left- and right-sided BH [6, 17, 18]. Under elective conditions, laparotomy or thoracotomy is performed for left-sided BH. Right-sided BH is generally dealt with using a thoracic or thoracoabdominal approach, because the right hepatic lobe obstructs an appropriate view to repair the defect [6]. Successful laparoscopic repair has recently been increasing for both left- and right-sided BH, even under emergency conditions [19–24]. In the current case, we detected an incidental right-sided BH before surgery for gastric cancer and planned to repair the right-sided BH concurrently with gastrectomy using a laparoscopic approach. The laparoscopic approach is minimally invasive and provides certain advantages over an open approach in terms of the surgical view to repair the defect, especially with the right-sided pathology, because the right hepatic lobe obstructs the surgical view and working space during diaphragmatic repair [20, 24]. We started laparoscopic gastrectomy under 10 cmH2O pressure of pneumoperitoneum. After creating pneumoperitoneum, no rise in airway pressure or decrease in pulse oximetry was seen, which indicated there was no tension pneumothorax in anesthesia. The surgery was subsequently continued using the same pneumoperitoneum pressure. During surgery, we observed the right-sided BH, and judged that repair was not needed because the right hepatic lobe that had herniated into the thorax cavity was adherent to the remnant right anterior hemidiaphragm and covered the huge defect in the right hemidiaphragm. Furthermore, the patient was asymptomatic and no progression of BH was seen between the preoperative CT for gastric cancer and CT before cervical cancer treatment. While adult BH is considered extremely rare and warrants repair regardless of symptoms, asymptomatic adult BH appears to be more common than previously reported. Surgeons should be aware of the presence of adult BH and consider whether repair is needed in the management of individual cases. A laparoscopic approach is useful to evaluate and repair BH, although surgeons have to be aware that intra- or postoperative pneumothorax can occur with pneumoperitoneum in this approach [25]. In the current case, no changes were observed on the monitor and vital signs remained stable intra- and postoperatively. No pneumothorax was observed on postoperative chest X-ray.

Conclusion

In summary, BH in adults appears to be more common than previously thought, and incidental BHs are increasing due to advances in imaging modalities. Thoracic and abdominal surgeons should be aware of the potential presence of BH in adults, and consider the management of incidental BHs at the time of surgery in individual cases.

Abbreviations

- BH:

-

Bochdalek hernia

- CT:

-

computed tomography

References

Bochdalek VA. Einige Betrachtungen über die Entstehung des angeborenen Zwerchfellbruches. Als Beitrag zur Anatomie der Hernien. Vierteljahrschrift prakt Heilunde. 1848;5:89–97.

Losanoff JE, Sauter ER. Congenital posterolateral diaphragmatic hernia in an adult. Hernia. 2004;8:83–5.

Bétrémieux P, Dabadie A, Chapuis M, Pladys P, Tréguier C, Frémond B, et al. Late presenting Bochdalek hernia containing colon: misdiagnosis risk. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 1995;5:113–5.

Gale ME. Bochdalek hernia: prevalence and CT characteristics. Radiology. 1985;156:449–52.

Brown SR, Horton JD, Trivette E, Hofmann LJ, Johnson JM. Bochdalek hernia in the adult: demographics, presentation, and surgical management. Hernia. 2011;15:23–30.

Rout S, Foo FJ, Hayden JD, Guthrie A, Smith AM. Right-sided Bochdalek hernia obstructing in an adult: case report and review of the literature. Hernia. 2007;11:359–62.

Mullins ME, Stein J, Saini SS, Mueller PR. Prevalence of incidental Bochdalek’s hernia in a large adult population. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;177:363–6.

Kinoshita F, Ishiyama M, Honda S, Matsuzako M, Oikado K, Kinoshita T, et al. Late-presenting posterior transdiaphragmatic (Bochdalek) hernia in adults: prevalence and MDCT characteristics. J Thorac Imaging. 2009;24:17–22.

Kubota K, Yamaguchi H, Kawahara M, Kaminishi M. Bochodalek hernia in a young adult: report of a case. Surg Today. 2001;31:322–4.

Goh BK, Teo MC, Chng SP, Soo KC. Right-sided Bochdalek’s hernia in an adult. Am J Surg. 2007;194:390–1.

Swain JM, Klaus A, Achem SR, Hinder RA. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia in adults. Semin Laparosc Surg. 2001;8:246–55.

Yamaguchi M, Kuwano H, Hashizume M, Sugio K, Sugimachi K, Hyoudou Y. Thoracoscopic treatment of Bochdalek hernia in the adult: report of a case. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2002;8:106–8.

Puri P, Wester T. Historical aspects of congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Pediatr Surg Int. 1997;12:95–100.

Temizöz O, Gençhellaç H, Yekeler E, Umit H, Unlü E, Ozdemir H, Demir MK, et al. Prevalence and MDCT characteristics of asymptomatic Bochdalek hernia in adult population. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2010;16:52–5.

Katz AS, Naidech HJ, Malhotra P. The air meniscus as a radiographic finding: a review of the literature and presentation of nine unusual cases. CRC Crit Rev Diagn Imaging. 1978;11:167–83.

Mullins ME, Saini S. Imaging of incidental Bochdalek hernia. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2005;26:28–36.

Soylu E, Junnarkar S, Kocher HM. Recurrent indigestion in a young adult. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2010;17:1497–8.

Kanazawa A, Yoshioka Y, Inoi O, Murase J, Kinoshita H. Acute respiratory failure caused by an incarcerated right-sided adult bochdalek hernia: report of a case. Surg Today. 2002;32:812–5.

Wadhwa A, Surendra JB, Sharma A, Khullar R, Soni V, Baijal M, et al. Laparoscopic repair of diaphragmatic hernias: experience of six cases. Asian J Surg. 2005;28:145–50.

Debergh I, Fierens K. Laparoscopic repair of a Bochdalek hernia with incarcerated bowel during pregnancy: report of a case. Surg Today. 2014;44:753–6.

Brusciano L, Izzo G, Maffettone V, Rossetti G, Renzi A, Napolitano V, et al. Laparoscopic treatment of Bochdalek hernia without the use of a mesh. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:1497–8.

Julien F, Drolet S, Lévesque I, Bouchard A. The right lateral position for laparoscopic diaphragmatic hernia repair in pregnancy: technique and review of the literature. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2011;21:67–70.

Harinath G, Senapati PS, Pollitt MJ, Ammori BJ. Laparoscopic reduction of an acute gastric volvulus and repair of a hernia of Bochdalek. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2002;12:180–3.

Rosen MJ, Ponsky L, Schilz R. Laparoscopic retroperitoneal repair of a right-sided Bochdalek hernia. Hernia. 2007;11:185–8.

Takeyama K, Nakahara Y, Ando S, Hasegawa K, Suzuki T. Anesthetic management for repair of adult Bochdalek hernia by laparoscopic surgery. J Anesth. 2005;19:78–80.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge all of the medical staff who took care of the patient.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article.

Authors’ contributions

SKi assisted with the surgery and wrote the manuscript. MN supervised the operation as the senior surgeon, and revised the manuscript. SKu performed the operation, and reviewed the manuscript. SKa reviewed the manuscript. As the chief of our division of gastroenterological surgery, TF revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

All authors are gastroenterological surgeons and specialists in gastroenterological surgery, and are certified by the Japanese Society of Gastroenterological Surgery. MN, SKu, and SKa are endoscopic surgical skill-qualified surgeons certified by the Japan Society for Endoscopic Surgery. TF is a professor in the Department of Gastroenterological Surgery at Okayama University, and a director and councilor of the Japan Surgical Society.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

In our institution, the need to obtain ethics approval for case reports is waived. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report. A copy of the consent form is available for review by the editors of this journal.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Kikuchi, S., Nishizaki, M., Kuroda, S. et al. A case of right-sided Bochdalek hernia incidentally diagnosed in a gastric cancer patient. BMC Surg 16, 34 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-016-0145-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-016-0145-2