Abstract

Nerve excitability studies have emerged as a recent novel non-invasive technique that offers complementary information to that provided by more conventional nerve conduction studies, the latter which provide only limited indices of peripheral nerve function. Such novel tools allow for the assessment of peripheral axonal biophysical properties that include ion channels, energy-dependent pumps and membrane potential in health and disease. With improvements in technique and development of protocols, a typical study can be completed in a short period of time and rapid measurement of multiple excitability indices can be achieved that provide insight into different aspects of peripheral nerve function. The advent of automated protocols for the assessment of nerve excitability has promoted their use in previous studies investigating disease pathophysiology such as in metabolic, toxic and demyelinating neuropathies, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, stroke, spinal cord injury and inherited channelopathies. In more recent years, the use of nerve excitability studies have additionally provided insights into the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying cerebellar disorders that include stroke and familial cerebellar ataxias such as episodic ataxia types 1 and 2. Moreover, this technique may have diagnostic and therapeutic implications that may encompass a broader range of neurodegenerative cerebellar ataxias in years to come. In the foreseeable future, this technique may eventually be incorporated into clinical practice expanding the currently available armamentarium to the neurophysiologist.

Similar content being viewed by others

Conventional nerve conduction studies (NCS) remain an important tool and in many respects, an extension of the clinical assessment in patients with neurological disorders, particularly those pertaining to the peripheral nervous system [1]. However, such techniques that employ supramaximal stimuli to measure amplitude and velocity of compound sensory or motor action potentials, provide information on only the number of conducting fibres and conduction velocity of the fastest, and hence only limited indices of peripheral nerve function.

In more recent years, a novel technique of axonal excitability has emerged and provide complementary information to those offered by conventional NCS [2]. Since the introduction of threshold measurements to study human motor axons in 1970 [3] and its first application in a clinical setting on diabetic patients [4], the technique has undergone modifications and refinement over the years with the development of protocols to allow the rapid measurement of multiple nerve excitability parameters in a short space of time and hence increasing the technique’s practicality when applied in a clinical environment [5].

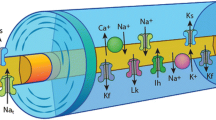

Axonal excitability techniques provide information related to activity of a variety of ion channels, energy-dependent pumps and ion exchange processes activated during impulse conduction in peripheral axons. While axonal membrane potential cannot be directly measured in intact human axons, indirect evidence may be obtained through assessment of the changes in axonal excitability measured through alterations in current required to elicit an action potential of a defined size [6]. “Threshold” refers to the stimulus current required to produce a predetermined target compound muscle action potential (CMAP) response (e.g., 40% of maximum) and can be that can be adjusted on-line by the computer software (“tracked”) during different manoeuvers (e.g., subthreshold conditioning) to follow changes in nerve excitability [7]. Measurement of threshold depends on and therefore provides an indirect measure of resting membrane potential. Furthermore, resting membrane potential is determined by a complex network of axonal membrane ion channels (persistent Na+ channels, slow and fast K+ channels) and the activity of the Na+/K+ pump [8] (Figure 1).

Diagram of a myelinated axon illustrating ion channels, pumps and exchangers responsible for determining axonal excitability. Transient Na+ channels (Nat) are clustered at high density at the node of Ranvier, with persistent Na+ channels (Nap) and slow K+ channels (Ks) contributing to excitability and resting membrane potential. Fast K+ channels (Kf) are located at highest density at the juxtaparanode, acting to limit re-excitation of the node following an action potential. Internodal conductances include voltage-independent ‘leak’ conductances (Lk) and hyperpolarization-activated cation conductance (IH). The Na+–K+ pump (Na+/K+-ATPase) utilises energy to maintain the electrochemical gradient necessary for impulse conduction by removing 3 Na+ ions for every 2 K+ ions pumped into the axon. The Na+–Ca2+ exchanger exports Ca2+ ions and imports Na+, driven by the electrochemical Na+ gradient. Paranodal myelin terminal loops are depicted with anchoring proteins to form paranodal junctions at the paranodal region.

With the development of the rapid automatic testing protocol known as “TROND” (names after a 3-day training symposium held in 1999 at Trondheim, Norway) and the threshold-tracking software QTRAC (© Institute of Neurology, Queen Square, London, UK) that runs the protocol, a set of axonal excitability indices are generated, that reflect the biophysical properties and membrane potential of the axon [9] (Figure 2).

Plots of excitability parameters recorded from abductor pollicis brevis in a single subject obtained from automated protocol. (A) Charge-duration relationship, in which intercept on stimulus width axis gives strength-duration time constant and slope gives rheobase. (B) Threshold electrotonus for 100 ms polarizing currents, ±40% of threshold. Responses to depolarizing currents start above the line and those to hyperpolarizing currents below the line. (C) Recovery cycle following supramaximal stimulation. (D) Current-threshold relationship.

These non-invasive techniques allow the assessment of axonal membrane function in vivo in a clinical setting, and provide insight into both normal nerve function and pathophysiological mechanisms in disease [10]. Over the years, nerve excitability studies have been utilized in a diverse range of conditions including toxic, metabolic, both acquired and inherited demyelinating neuropathies, neurodegenerative disorders such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, as well as providing insight into pathophysiological changes occurring at the peripheral nerve level in disorders of the central nervous system such as stroke, spinal cord injury and multiple sclerosis [7,11-32]. In more recent years, the use of nerve excitability studies have provided further insights into the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying cerebellar disorders that include stroke and familial cerebellar ataxias such as episodic ataxia types 1 and 2 [33-35]. In addition, this technique may have diagnostic and therapeutic implications that may encompass a broader range of neurodegenerative cerebellar ataxias in years to come.

The peripheral nerve excitability changes observed in ischemic stroke involving the cerebellum may be a reflection of a transynaptic plastic process or alterations in activity of the limb(s) that result from the resultant functional deficit [13,15]. Downstream peripheral nerve excitability changes have been observed in post-stroke patients involving motor pathways in the brain that may reflect alterations in inward rectifying (I H ) and slow K+ conductance, suggesting that transynaptic plasticity in peripheral motor axons develop in response to a remote lesion in the central nervous system [14,15], possibly reflecting an alteration or disturbance in supraspinal circuitry and thereby input to spinal motoneurons, consequently resulting in changes in their axonal physiology [11,36]. As such, the biophysical changes present in cerebellar stroke patients may be a consequence of a downstream transynaptic plastic process following changes in excitability reported to occur in both motor cortices in cerebellar stroke [37]. Additionally, the intricate connections that exist between the deep cerebellar nuclei and motoneurons of the cervical spinal cord, may mean that lesions involving these deep cerebellar structures may ultimately affect excitability of downstream lower motor neurons within the circuitry [38-41].

Genetic neuronal channelopathies commonly manifest with paroxysmal symptoms that may vary considerable between patients rendering diagnosis an often challenging feat. In patients with episodic ataxia type 1 (EA1), mutations in KCNA1 gene result in alterations in fast K+ channel function. Specifically, the gene encodes for the α subunit of the Kv1.1 channel. With such channels also present at the juxtaparanodal region of peripheral axons, a specific pattern of nerve excitability abnormalities in patients with EA1 have been observed which do not appear to be different amongst the different mutations [34]. Moreover, there are patients with EA1 who present with a predominantly peripheral phenotype but with typical EA1 changes observed in nerve excitability parameters rendering this a potential useful diagnostic tool in identifying those patients with an atypical presentation [33]. Of further relevance, the changes in parameters in EA1 differ from those seen in acquired autoimmune neuromyotonia (Isaac’s syndrome) which is a channelopathy affecting the same K+ channels, suggesting a pathophysiologically different effect on these channels along the axon between the two conditions . Studies on patients with episodic ataxia type 2 (EA2) have also shown a unique pattern of nerve excitability alterations. Mutations of the CACNA1A gene that encodes the Cav2.1 subunit of the voltage-gated Ca2+ channels represent the genetic defect underlying this disorder, and the changes observed in axonal function are postulated to have been a result of Ca2+ channel dysfunction which consequently affect the function of slow K+ channels [35].

Studies have shown changes in voltage-gated K+ channel kinetics present in the cerebellum of murine models with spinocerebellar ataxia type 3 (SCA3) that precede the onset of Purkinje cell loss [42]. Based on these preliminary observations, future studies utilizing nerve excitability in human patients with the spinocerebellar ataxia may allow for the development of a diagnostic electrophysiological biomarker.

Taken together, nerve excitability studies may provide for a sensitive technique that can be applied in a quick and non-invasive manner to facilitate the diagnosis of a range of acquired autoimmune or neurodegenerative as well as genetic cerebellar disorders.

Studies of nerve excitability in chemotherapy-induced neurotoxicity have provided insight into the pathophysiological mechanisms involved and enable early identification of neurotoxicity thereby optimizing treatment strategies and improving patient quality of life in cancer patients [43]. Assessment of motor and sensory nerve function in many chemotherapy-induced neuropathies using conventional NCS has revealed significant reductions in compound sensory action potential (CSAP) amplitude whilst CMAP and conduction velocities are often preserved, consistent with a sensory neuropathy of the axonal type [20,44]. Studies of sensory nerve excitability have demonstrated a direct effect of oxaliplatin on nerve excitability, with changes in sensory axons immediately following infusion similar to those seen with the Na+ channel blocker tetrodotoxin [19], suggesting partial blockade of axonal Na+ channels [9,20,22]. Longitudinal assessment of axonal excitability have shown that before each successive oxaliplatin treatment, progressive changes in nerve excitability with increased cumulative dosing were observed [45]. There were significant changes in threshold electrotonus and recovery cycle indices. Importantly, progressive changes in sensory nerve excitability across treatment cycles occur before reductions in peak CSAP amplitude are detected [46]. This suggests that such changes may be able to identify at-risk patients prior to the development of chronic neuropathy [47,48].

In diabetic neuropathy patient, studies of nerve excitability have demonstrated alterations in threshold electrotonus consistent with reductions in Na+/K+ pump function, that subsequently improved following strict glycemic control [23,49]. Other studies have suggested changes in on Na+ channel function with alterations in recovery cycle parameters [50]. Recent studies have also shown marked improvement in nerve excitability parameters in patients treated with continuous insulin therapy compared to other regimens [51]. More importantly, changes in nerve excitability preceded the development of neuropathy in diabetic patients thus providing a promising biomarker for detecting preclinical neuropathy in such patients [52,53]. Furthermore, in those patients with typical neuropathic symptoms that may reflect small fibre neuropathy and hence normal results on conventional nerve conduction studies, nerve excitability techniques offer a more sensitive way to establish the presence of altered nerve function underlying these symptoms and providing a potential biomarker to aid the treatment of symptoms in these patients.

Excitability studies in patients with chronic kidney disease and neuropathy have demonstrated significant changes consistent with axonal depolarization driven by hyperkalemia prior to dialysis that normalized following such renal replacement therapies [21,54]. Such techniques have also provided insight into the differential effects of various haemodialysis regimens on nerve function [55], as well as potential neurotoxic effects of various immunosuppressants following renal transplant [56], allowing for the appropriate selection of management strategies involved in renal replacement.

In summary, nerve excitability techniques are a powerful and novel non-invasive means of detecting alterations in axonal biophysical properties that may potentially expand the current armamentarium available to the clinical neurophysiologist. The recent development of commercially available software and hardware represent a step toward implementing these techniques as a clinical diagnostic tool. These measurements are not only important

in investigating the pathophysiology of disorders of the peripheral and to a lesser degree the central nervous systems, they will play a significant role in charting disease progress, and detecting subclinical alterations in nerve function in neuropathies and during treatment with potentially neurotoxic drugs. This in turn will aid in the development of novel therapies for disorders of the nervous system.

References

Huynh W, Kiernan MC. Nerve conduction studies. Aust Fam Physician. 2011;40(9):693–7.

Bostock H, Cikurel K, Burke D. Threshold tracking techniques in the study of human peripheral nerve. Muscle Nerve. 1998;21(2):137–58.

Bergmans J. The Physiology of Single Human Nerve Fibres. Vander, Belgium: University of Louvain; 1970.

Weigl P, Bostock H, Franz P, Martius P, Muller W, Grafe P. Threshold tracking provides a rapid indication of ischaemic resistance in motor axons of diabetic subjects. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1989;73(4):369–71.

Kiernan MC, Burke D, Andersen KV, Bostock H. Multiple measures of axonal excitability: a new approach in clinical testing. Muscle Nerve. 2000;23(3):399–409.

Krishnan AV, Lin CSY, Park SB, Kiernan MC. Axonal ion channels from bench to bedside: a translational neuroscience perspective. Prog Neurobiol. 2009;89(3):288–313.

Krishnan AV, Lin CS, Park SB, Kiernan MC. Assessment of nerve excitability in toxic and metabolic neuropathies. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2008;13(1):7–26.

Burke D, Kiernan MC, Bostock H. Excitability of human axons. Clin Neurophysiol. 2001;112(9):1575–85.

Park SB, Lin CS, Kiernan MC: Nerve excitability assessment in chemotherapy-induced neurotoxicity. J Visual Exp: 2012(62).

Kuwabara S, Bostock H, Ogawara K, Sung J-Y, Misawa S, Kitano Y, et al. Excitability properties of human median axons measured at the motor point. Muscle Nerve. 2004;29(2):227–33.

Huynh W, Krishnan AV, Lin CS, Vucic S, Katrak P, Hornberger M, et al. Botulinum toxin modulates cortical maladaptation in post-stroke spasticity. Muscle Nerve. 2013;48(1):93–9.

Huynh W, Krishnan AV, Lin CS, Vucic S, Kiernan MC. The effects of large artery ischemia and subsequent recanalization on nerve excitability. Muscle Nerve. 2011;44(5):841.

Huynh W, Lin CS, Krishnan AV, Vucic S, Kiernan MC. Transynaptic changes evident in peripheral axonal function after acute cerebellar infarct. Cerebellum. 2014;13(6):669–76.

Huynh W, Vucic S, Krishnan AV, Lin CS, Hornberger M, Kiernan MC. Longitudinal plasticity across the neural axis in acute stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2013;27(3):219–29.

Jankelowitz SK, Howells J, Burke D. Plasticity of inwardly rectifying conductances following a corticospinal lesion in human subjects. J Physiol. 2007;581(Pt 3):927–40.

Kiernan MC, Bostock H. Effects of membrane polarization and ischaemia on the excitability properties of human motor axons. Brain. 2000;123(Pt 12):2542–51.

Kiernan MC, Burke D, Bostock H. Nerve excitability measures: biophysical basis and use in the investigation of peripheral nerve disease. In: Dyck PJ, Thomas PK, editors. Peripheral Neuropathy. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2005. p. 113–30.

Kiernan MC, Guglielmi JM, Kaji R, Murray NM, Bostock H. Evidence for axonal membrane hyperpolarization in multifocal motor neuropathy with conduction block. Brain. 2002;125(Pt 3):664–75.

Kiernan MC, Isbister GK, Lin CS, Burke D, Bostock H. Acute tetrodotoxin-induced neurotoxicity after ingestion of puffer fish. Ann Neurol. 2005;57(3):339–48.

Kiernan MC, Krishnan AV, Kiernan MC, Krishnan AV. The pathophysiology of oxaliplatin-induced neurotoxicity. Curr Med Chem. 2006;13(24):2901–7.

Kiernan MC, Walters RJ, Andersen KV, Taube D, Murray NM, Bostock H. Nerve excitability changes in chronic renal failure indicate membrane depolarization due to hyperkalaemia. Brain. 2002;125(Pt 6):1366–78.

Krishnan AV, Goldstein D, Friedlander M, Kiernan MC. Oxaliplatin and axonal Na + channel function in vivo. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(15):4481–4.

Krishnan AV, Kiernan MC. Altered nerve excitability properties in established diabetic neuropathy. Brain. 2005;128(Pt 5):1178–87.

Krishnan AV, Kiernan MC. Uremic neuropathy: clinical features and new pathophysiological insights. Muscle Nerve. 2007;35(3):273–90.

Krishnan AV, Kiernan MC. Activity-dependent excitability changes suggest Na+/K+ pump dysfunction in diabetic neuropathy. Brain. 2008;131(5):1209–16.

Krishnan AV, Park SB, Huynh W, Lin CS, Henderson RD, Kiernan MC. Impaired energy-dependent processes underlie acute lead neuropathy. Muscle Nerve. 2012;46(6):957–61.

Kuwabara S, Ogawara K, Sung JY, Mori M, Kanai K, Hattori T, et al. Differences in membrane properties of axonal and demyelinating Guillain-Barre syndromes. Ann Neurol. 2002;52(2):180–7.

Cappelen-Smith C, Kuwabara S, Lin CS, Burke D. Abnormalities of axonal excitability are not generalized in early multifocal motor neuropathy. Muscle Nerve. 2002;26(6):769–76.

Cappelen-Smith C, Kuwabara S, Lin CS, Mogyoros I, Burke D. Activity-dependent hyperpolarization and conduction block in chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy. Ann Neurol. 2000;48(6):826–32.

Sung JY, Kuwabara S, Kaji R, Ogawara K, Mori M, Kanai K, et al. Threshold electrotonus in chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy: correlation with clinical profiles. Muscle Nerve. 2004;29(1):28–37.

Vucic S, Kiernan MC, Vucic S, Kiernan MC. Axonal excitability properties in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Clin Neurophysiol. 2006;117(7):1458–66.

Farrar MA, Lin CSY, Krishnan AV, Park SB, Andrews PI, Kiernan MC. Acute, reversible axonal energy failure during stroke-like episodes in MELAS. Pediatrics. 2010;126(3):e734–9.

Tan SV, Wraige E, Lascelles K, Bostock H. Episodic ataxia type 1 without episodic ataxia: the diagnostic utility of nerve excitability studies in individuals with KCNA1 mutations. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2013;55(10):959–62.

Tomlinson SE, Tan SV, Kullmann DM, Griggs RC, Burke D, Hanna MG, et al. Nerve excitability studies characterize Kv1.1 fast potassium channel dysfunction in patients with episodic ataxia type 1. Brain. 2010;133(Pt 12):3530–40.

Krishnan AV, Bostock H, Ip J, Hayes M, Watson S, Kiernan MC. Axonal function in a family with episodic ataxia type 2 due to a novel mutation. J Neurol. 2008;255(5):750–5.

Kiernan MC, Vucic S, Cheah BC, Turner MR, Eisen A, Hardiman O, et al. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet. 2011;377(9769):942–55.

Huynh W, Krishnan AV, Vucic S, Lin CS, Kiernan MC. Motor cortex excitability in acute cerebellar infarct. Cerebellum. 2013;12(6):826–34.

McLeod JG. H reflex studies in patients with cerebellar disorders. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1969;32(1):21–7.

Chen XY, Wolpaw JR. Ablation of cerebellar nuclei prevents H-reflex down-conditioning in rats. Learn Mem. 2005;12(3):248–54.

Wolpaw JR, Chen XY. The cerebellum in maintenance of a motor skill: a hierarchy of brain and spinal cord plasticity underlies H-reflex conditioning. Learn Mem. 2006;13(2):208–15.

Haines DE, Dietrichs E. The cerebellum - structure and connections. Handbook of clinical neurology / edited by PJ Vinken and GW Bruyn. 2012;103:3–36.

Shakkottai VG, Do Carmo Costa M, Dell’Orco JM, Sankaranarayanan A, Wulff H, Paulson HL. Early changes in cerebellar physiology accompany motor dysfunction in the polyglutamine disease spinocerebellar ataxia type 3. J Neurosci. 2011;31(36):13002–14.

Park SB, Goldstein D, Lin CS, Krishnan AV, Friedlander ML, Kiernan MC. Neuroprotection for oxaliplatin-induced neurotoxicity: what happened to objective assessment? J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2011;29(18):e553–4. author reply e555-556.

Krishnan AV, Goldstein D, Friedlander M, Kiernan MC. Oxaliplatin-induced neurotoxicity and the development of neuropathy. Muscle Nerve. 2005;32(1):51–60.

Park SB, Lin CS, Krishnan AV, Goldstein D, Friedlander ML, Kiernan MC. Dose effects of oxaliplatin on persistent and transient Na + conductances and the development of neurotoxicity. PLoS One. 2011;6(4):e18469.

Park SB, Koltzenburg M, Lin CS, Kiernan MC. Longitudinal assessment of oxaliplatin-induced neuropathy. Neurology. 2012;78(2):152.

Park SB, Lin CS, Krishnan AV, Goldstein D, Friedlander ML, Kiernan MC. Oxaliplatin-induced neurotoxicity: changes in axonal excitability precede development of neuropathy. Brain. 2009;132(Pt 10):2712–23.

Park SB, Lin CS, Krishnan AV, Goldstein D, Friedlander ML, Kiernan MC. Long-term neuropathy after oxaliplatin treatment: challenging the dictum of reversibility. Oncologist. 2011;16(5):708–16.

Kuwabara S, Ogawara K, Harrori T, Suzuki Y, Hashimoto N. The acute effects of glycemic control on axonal excitability in human diabetic nerves. Intern Med. 2002;41(5):360–5.

Misawa S, Kuwabara S, Ogawara K, Kitano Y, Yagui K, Hattori T, et al. Hyperglycemia alters refractory periods in human diabetic neuropathy. Clin Neurophysiol. 2004;115(11):2525–9.

Kwai N, Arnold R, Poynten AM, Lin CS, Kiernan MC, Krishnan AV. Continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion preserves axonal function in type 1 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes/Metabol Res Rev. 2015;31(2):175–82.

Arnold R, Kwai N, Lin CS, Poynten AM, Kiernan MC, Krishnan AV. Axonal dysfunction prior to neuropathy onset in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2013;29(1):53–9.

Sung JY, Park SB, Liu YT, Kwai N, Arnold R, Krishnan AV, et al. Progressive axonal dysfunction precedes development of neuropathy in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2012;61(6):1592–8.

Arnold R, Pussell BA, Howells J, Grinius V, Kiernan MC, Lin CS, et al. Evidence for a causal relationship between hyperkalaemia and axonal dysfunction in end-stage kidney disease. Clin Neurophysiol. 2014;125(1):179–85.

Arnold R, Pussell BA, Pianta TJ, Grinius V, Lin CS, Kiernan MC, et al. Effects of hemodiafiltration and high flux hemodialysis on nerve excitability in end-stage kidney disease. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e59055.

Arnold R, Pussell BA, Pianta TJ, Lin CS, Kiernan MC, Krishnan AV. Association between calcineurin inhibitor treatment and peripheral nerve dysfunction in renal transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2013;13(9):2426–32.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

WH prepared, drafted and edited manuscript. MK edited the final manuscript draft. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Huynh, W., Kiernan, M.C. Peripheral nerve axonal excitability studies: expanding the neurophysiologist’s armamentarium. cerebellum ataxias 2, 4 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40673-015-0022-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40673-015-0022-2