Abstract

Background

A recent prospective trial using porcine models of severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) indicated that positive-pressure ventilation delivered by a conventional intensive care ventilator at a moderately high frequency allows safe reduction of tidal volume below 6 ml/kg, leading to more protective ventilation. We aimed to explore whether these results would be replicated when implementing similar ventilation strategies in a high-fidelity computational simulator, tuned to match data on the responses of a number of human ARDS patients to different ventilator inputs.

Methods

We evaluated three different strategies for managing the trade-off between increasing respiratory rate and reducing tidal volume while attempting to maintain the partial pressure of carbon dioxide in arterial blood (PaCO2) constant on a computational simulator configured with ARDS patient datasets.

Results

For a fixed sequence of stepwise increases in the respiratory rate, corresponding decreases in tidal volume to keep the alveolar minute ventilation and inspiratory flow constant were calculated according to standard formulae. When applied on the simulator, however, these sequences of ventilator settings failed to maintain PaCO2 adequately in the virtual patients considered. In contrast, an approach based on combining numerical optimisation methods with computational simulation allowed a sequence of tidal volume reductions to be computed for each virtual patient that maintained PaCO2 levels while significantly reducing peak airway pressures and dynamic alveolar strain in all patients.

Conclusions

Our study supports the proposition that moderately high-frequency respiratory rates can allow more protective ventilation of ARDS patients and highlights the potential role of high-fidelity simulators in computing optimised and personalised ventilator settings for individual patients using this approach.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is a severe condition that affects around 1 in 10,000 people every year with the mortality rate of 40–50 % [1, 2]. Mechanical ventilation (MV), involving the use of mechanical force to offload respiratory muscles of their work, is a fundamental component of treatment in the intensive care unit (ICU) for patients with ARDS. However, a problematic issue associated with MV is that it exposes patients’ lungs to potentially destructive energy applied by the ventilator [3]. Consequently, MV can induce lung injury and can increase the risk of non-pulmonary organ injury/failure, which further adds to morbidity and mortality for ARDS patients [4].

A number of studies have shown that lowering the tidal volume (V T) can improve mortality rates in ARDS patients. Hickling et al. [5] reported a 60 % decrease in the expected mortality rate among patients with ARDS by lowering V T. In another trial, Amato et al. [6] investigated changing conventional V T (12 ml/kg of predicted body weight, PBW) to low V T and reported a 46 % reduction in mortality. This benefit was also confirmed in the ARDS Network study with mortality decreased by 22 % in the low tidal volume intervention group [7]. However, reducing V T by itself also leads to worsened partial pressures of arterial oxygen (PaO2) and carbon dioxide (PaCO2) and arterial pH [8].

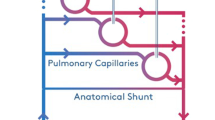

An alternative approach to achieve more protective ventilation is high-frequency oscillatory ventilation (HFOV) [9]. In this approach, patients’ lungs are not allowed to exhale fully (keeping them partially inflated, which maintains oxygenation), while CO2 is cleared by moving small volumes of gas in and out of the respiratory system at 3 to 15 Hz (180 to 900 b/min). This process has the potential to minimise the repeated opening and collapsing of lung units that can cause secondary lung damage during mechanical ventilation [10]. Although HFOV is now a widely used lung-protective strategy in the treatment of neonatal and paediatric acute lung injury [11], it cannot be implemented on conventional ventilators, and clinical studies have so far failed to show a significant effect on mortality in adult patients undergoing mechanical ventilation for ARDS [12, 13].

A number of previous studies have also investigated the potential of moderately high-frequency ventilation using standard ventilators [14, 15]. In this approach, respiratory rates (RRs) applied are beyond the limits of traditional mechanical ventilation but below those used in HFOV. A recent prospective study using porcine models (N = 8) in which ARDS was induced by pulmonary lavage and injurious ventilation [16] supported the potential of moderately high-frequency ventilation to allow safe reductions in V T and airway pressures while maintaining stable PaCO2 levels.

In this study, we explore whether the application of a similar approach using a high-fidelity computational simulator tuned to a number of human ARDS patient datasets confirms or refutes the results of this previous animal study. We also investigate a number of different approaches for practically implementing moderately high-frequency ventilation, by considering alternative algorithms for maintaining PaCO2 and reducing alveolar strain.

Methods

Computational simulator

The computational simulator used in this study is a multi-compartmental computational model that uses an iterative, time-sliced, arithmetic technique to simulate integrated respiratory and cardiovascular pathophysiological scenarios [17–19]. The core models in the simulator have been designed to represent a dynamic in vivo cardiovascular-pulmonary state using a set of mass-conserving equations based on well-established physiological principles. The model simulates a lung comprising conducting airways and 100 alveolar compartments, with each compartment having a corresponding set of parameters accounting for stiffness, threshold opening pressures (TOPs) and extrinsic pressures as well as airway and peri-alveolar vascular resistances. The mathematical principles and equations on which the simulator is based have been detailed in previous studies [20–22], which have also validated the simulator’s ability to represent the pulmonary disease states of individual patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and ARDS. A detailed description of the principles and mathematical equations underlying the computational model implemented in our simulator is provided in Additional file 1.

Model matching to ARDS patient data

The model was configured to match data from individual ARDS patients reported by Nirmalan and colleagues [23], which listed arterial and mixed venous blood gas values and cardiac output measurements taken from patients treated for ARDS. The problem of matching the model’s outputs to the patient data reported in [23] was formulated as an optimisation problem, where the difference between the simulated model outputs and the data is measured by a cost function. Internal model parameters are then varied by a numerical optimisation algorithm [24] in order to minimise this cost function. The cost function that captures the matching error between the model and the data is defined as:

where E T is the total residual error representing the matching accuracy and \( {E}_i=\frac{x_i-{x}_{id}}{x_{id}} \) is the error for output i, x i is the value of output i returned by the simulation and x id is the value of the data for that output. The model parameters for each compartment i used for the matching include threshold opening pressure TOP i , stiffness coefficient S i and extrinsic pressure P ext,i , meaning that a total of 300 model parameters are considered for 100 compartments in the simulator. During the matching process, these parameters are allowed to vary continuously between physiologically realistic upper and lower bounds as defined in Table 1.

Global optimisation algorithms can then be used to find model parameter values that minimise the value of E T, i.e. minimise the difference between the model outputs and the data. The procedure is illustrated in detail in Additional file 1—in each iteration, a set of parameter combinations are sent to the simulator and the outputs from the simulator are evaluated by the optimisation algorithm which then generates the updated parameter values for the next iteration until the condition to get a best matching is found. In this study, we employed an advanced global optimisation algorithm known as a genetic algorithm, a general-purpose, stochastic search and optimisation procedure, based on genetic and evolutionary principles [24]. Full details of the particular optimisation algorithm used in this study and how it was implemented with the model are also provided in Additional file 1.

Strategies for implementing moderately high-frequency ventilation

After matching the model to the patient datasets, three different ventilation strategies were applied and evaluated separately on each of the virtual patients. The primary objective of the ventilation strategies was always to maintain a constant PaCO2 while increasing RR and reducing V T.

Strategy 1

The first two strategies attempt to calculate appropriate ventilator settings based on simple physiological equations that are widely used in clinical practice. To maintain PaCO2, patients are expected to have constant alveolar minute ventilation, which can be calculated using the following equation [25]:

In Eq. (2), M Valv is the alveolar minute ventilation, RR is the respiratory rate, V T is the tidal volume and V Danat is the anatomical dead space. To investigate the effect of higher frequency ventilation, the ventilator rate RR for each of the virtual patients is increased from 16 to 48 b/min in steps of 8 b/min, with each step lasting for 20 min. At each step, the corresponding V T is reduced according to Eq. (2) above, so as to maintain constant alveolar minute ventilation. V Danat can be estimated based on the ideal body weight [26]; in this study, we used a value of 160 ml, based on an adult patient with ideal body weight of 70 kg.

Strategy 2

Here, as well as keeping alveolar minute ventilation constant using Eq. (2), the inspiratory flow is also kept constant (this corresponds to the strategy implemented in [16]). This can be achieved in our simulator by using the equation [25]:

where F insp is the inspiratory flow into the lung from the ventilator and DC is the duty cycle (inspiratory time divided by total cycle time). From Eq. (3), by varying DC, F insp can be manipulated since V T is already determined by Eq. (2). Thus, the difference between strategies 1 and 2 is that DC is set as constant for the first, while for the latter, DC is varied to achieve constant inspiratory flow.

Strategy 3

An alternative approach to computing changes in ventilator settings based on simple physiological equations is to exploit the computational simulator directly. In this approach, we use numerical optimisation to calculate the value of V T at each increment of RR that will minimise the change in the value of PaCO2. For each value of RR from 16 to 48 b/min at each step, the corresponding values of V T (denoted by p 1, p 2,…, p 5) are selected by an optimisation algorithm between a lower bound of 2.5 ml/kg and an upper bound of 8 ml/kg. A cost function is defined as the difference between the model-generated values and the initial value of PaCO2. During the optimisation process, the values of p i are considered as optimisation variables that are systematically varied within the bounded space until the values that minimise the cost function are found. The process is then repeated for all three patient models.

Results

Matching the simulator to ARDS patient datasets

To configure the virtual ARDS patients, three sets of patient data from Nirmalan’s study [23] were used, which are classified as mild (patient A, partial pressure of arterial oxygen/fraction of inspired oxygen (PaO2/FIO2) ratio 253.9 mmHg), moderate (patient B, PaO2/FIO2 ratio 166.3 mmHg) and severe (patient C, PaO2/FIO2 ratio 55.6 mmHg) according to the ARDS Berlin definition [27]. The initial V T was set at 8 ml/kg (assuming ideal body weight of 70 kg), and RR was set to 12.5 b/min for all three patients. The cardiac output (CO), FiO2 and haemoglobin (Hb) were configured using the data reported in the reference. Pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) and compliance used for the model are also reported in Table 2. The model outputs to be matched included PaO2, partial pressure of oxygen in mixed venous blood (PvO2), partial pressure of carbon dioxide in the venous blood (PvCO2) and pulmonary shunt fraction. The initial value of PaCO2 was produced by the model at the matched state. An optimisation algorithm was run to minimise the difference between model outputs and the data based on Eq. (1), until a predefined termination criterion was reached. The model-fitting results are reported in Table 2; this shows that close matches to each of the three patient datasets were achieved by the simulator.

Effectiveness of the three ventilation strategies

The ventilation settings used for each strategy are reported in Table 3 and are also shown in Fig. 1. For strategies 1 and 2, the same settings for V T are applied to each patient; see Fig. 1a. For strategy 3, the optimal values of V T are computed for each patient using numerical optimisation; see Fig. 1b. Figure 1c shows the same pattern of RR applied for all strategies, and the variations of DC are shown in Fig. 1d. The corresponding changes of the P/F ratio, PaCO2, peak alveolar pressure (P alv, calculated from the 25 % of alveoli with highest pressures), dynamic compliance (C dyn) and the volume of the lung at the end of inhalation and exhalation (V lung) for each patient are shown in Figs. 2, 3 and 4. For all patients, strategies 1 and 2 led to significant changes in PaCO2, whereas strategy 3 kept the value of PaCO2 almost constant for all combinations of V T and RR. The changes in PaCO2 observed for strategies 1 and 2 are accompanied by large increases in the P/F ratio (due to alveolar recruitment arising from increases in P alv)—only strategy 3 showed a consistent reduction in P alv as RR increased, i.e. only strategy 3 implemented a more protective ventilation strategy. The potential of moderately high-frequency ventilation to deliver more protective ventilation is further supported by Fig. 5, where dynamic strain (V T/FRC, ratio) can be seen to decrease most significantly in all three simulated patients as RR is increased using strategy 3.

Discussion

Why do strategies 1 and 2 result in large changes in PaCO2 when they are predicated on maintaining constant alveolar minute ventilation and inspiratory flow? The answer is provided by Fig. 6, which plots the relationship between the total dead space (physiological dead space, V Dphys) calculated in the simulation model and V T for each virtual patient. As shown, as RR increases, the value of V Dphys is not constant, as assumed in Eqs. (2) and (3) using V Danat (on which strategies 1 and 2 are based), but is strongly proportional to V T. It may also be observed that the ratio V Dphys/V T is similar through the spectrum of ARDS severity. Interestingly, this relationship has previously been shown experimentally in the context of high-frequency ventilation [28]. Thus, the simple formulae on which strategies 1 and 2 are based do not correctly compute the required changes in V T and RR to keep alveolar minute ventilation constant with either constant or variable inspiratory flow.

A test was performed using the model that calculated V Dphys instead of V Danat during each step to estimate which V T should be applied in the next change of RR to maintain M Valv based on Eq.(2). The simulation results for patient C using strategy 1 with the calculated V Dphys are shown in Fig. 7. It can be seen that although PaCO2 was not constant, it remained within an acceptably narrow range, which is significantly improved compared with the results in Fig. 4. In practice, therefore, if a device could provide a measurement of V Dphys in a sufficiently short time, our results indicate that PaCO2 could be well controlled using this approach.

The benefits of a normal or only slightly elevated level of PaCO2 in critically ill patients are well recognised. It is, however, difficult and sometimes impossible to achieve this in a patient with ARDS without increasing the risk of alveolar injury. The concept of permissive hypercapnia is now an accepted management strategy for the critically ill lung. The rationale behind this approach is primarily to minimise lung strain, which could otherwise be worsened by strenuous ventilatory strategies aimed at keeping PaCO2 within normal physiological limits. However, in a very severe lung disease, the rise in PaCO2 is sometimes difficult to control using conventional protective ventilation strategies. Extracorporeal CO2 removal devices have been used in clinical practice for a few years now, but they bring potentially dangerous side effects [29]. The efficacy of these devices in allowing ultra-protective ventilation strategies, with tidal volumes and pressures comparable to those used in our model simulation, is being tested at present in the SUPERNOVA trial [30].

The benefit of the moderately high-frequency ventilation strategies we tested in this model is that they allow the maintenance of a normal level of PaCO2 while seeming to have the potential for decreasing the risk of lung injury and, in some cases, while recruiting the lung. The problem of improving lung protection in ARDS is obviously an extremely complex and multifaceted one and involves consideration of multiple factors beyond mechanical pressure limits. Nonetheless, our results indicate that moderately high-frequency ventilation could represent a beneficial ventilation strategy in ARDS patients with reduced respiratory system compliance. An interesting question for future investigation is to determine the potential for reducing driving pressure using this strategy, since a recent retrospective analysis of nine randomised trials indicated that driving pressure was the variable most strongly associated with survival [31]. Our study has a number of limitations, principally the small number of “virtual” patients evaluated and the lack of prospective validation in clinical trials. We note, however, that our findings confirm and help to explain the results of a previous study using animal models that investigated very similar changes in ventilator settings [16].

Conclusions

By using a high-fidelity computational simulator, a more protective ventilation strategy consisting of progressive reductions in V T with simultaneous increases in RR could be developed for a number of different virtual ARDS patients, covering the spectrum from mild to severe presentations of the disease. This strategy allowed changes in PaCO2 to be kept within an acceptable range in each case, thus confirming the results reported on a cohort of porcine models in [16], which showed that moderately high-frequency ventilation could allow safe reductions in the levels of V T. Attempts to compute appropriate values for the decrements in V T required to compensate for increments in RR using simple mathematical formulae were not successful, due to the fact that dead space varies significantly with changes in V T. Our results demonstrate the importance of using advanced simulation models in order to correctly represent the complex dynamics of ventilator-lung interactions and highlight the potential of such models to refine or replace animal trials in this area.

References

Villar J, Blanco J, Añón JM, Santos-Bouza A, Blanch L, Ambrós A, Gandía F, Carriedo D, Mosteiro F, Basaldúa S (2011) The ALIEN study: incidence and outcome of acute respiratory distress syndrome in the era of lung protective ventilation. Intensive Care Medicine 37(12):1932–1941

Erickson SE, Martin GS, Davis JL, Matthay MA, Eisner MD (2009) Recent trends in acute lung injury mortality: 1996–2005. Critical Care Medicine 37(5):1574

Zilberberg MD, de Wit M, Pirone JR, Shorr AF (2008) Growth in adult prolonged acute mechanical ventilation: implications for healthcare delivery. Critical Care Medicine 36(5):1451–1455

Slutsky AS, Tremblay LN (1998) Multiple system organ failure: is mechanical ventilation a contributing factor? American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 157(6):1721–1725

Hickling K, Henderson S, Jackson R (1990) Low mortality associated with low volume pressure limited ventilation with permissive hypercapnia in severe adult respiratory distress syndrome. Intensive Care Medicine 16(6):372–377

Amato MBP, Barbas CSV, Medeiros DM, Magaldi RB, Schettino GP, Lorenzi-Filho G, Kairalla RA, Deheinzelin D, Munoz C, Oliveira R (1998) Effect of a protective-ventilation strategy on mortality in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. New England Journal of Medicine 338(6):347–354

Network ARDS (2000) Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. New England Journal of Medicine 342(18):1301–1308

Fuchs H, Mendler MR, Scharnbeck D, Ebsen M, Hummler HD (2011) Very low tidal volume ventilation with associated hypercapnia-effects on lung injury in a model for acute respiratory distress syndrome. PloS One 6(8), e23816

Derdak S, Mehta S, Stewart TE, Smith T, Rogers M, Buchman TG, Carlin B, Lowson S, Granton J, Investigators MOVFARDSTS (2002) High-frequency oscillatory ventilation for acute respiratory distress syndrome in adults: a randomized, controlled trial. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 166(6):801–808

Riphagen S, Bohn D (1999) High frequency oscillatory ventilation. Intensive Care Medicine 25(12):1459–1462

Graciano AL, Freid EB (2002) High-frequency oscillatory ventilation in infants and children. Current Opinion in Anesthesiology 15(2):161–166

Young D, Lamb SE, Shah S, MacKenzie I, Tunnicliffe W, Lall R, Rowan K, Cuthbertson BH (2013) High-frequency oscillation for acute respiratory distress syndrome. New England Journal of Medicine 368(9):806–813

Ferguson ND, Cook DJ, Guyatt GH, Mehta S, Hand L, Austin P, Zhou Q, Matte A, Walter SD, Lamontagne F (2013) High-frequency oscillation in early acute respiratory distress syndrome. New England Journal of Medicine 368(9):795–805

Eriksson I, Sjöstrand U (1980) Effects of high-frequency positive-pressure ventilation (HFPPV) and general anesthesia on intrapulmonary gas distribution in patients undergoing diagnostic bronchoscopy. Anesthesia & Analgesia 59(8):585–593

Barzilay E, Lev A, Ibrahim M, Lesmes C (1987) Traumatic respiratory insufficiency: comparison of conventional mechanical ventilation to high-frequency positive pressure with low-rate ventilation. Critical Care Medicine 15(2):118–121

Cordioli RL, Park M, Costa ELV, Gomes S, Brochard L, Amato MBP, Azevedo LCP (2014) Moderately high frequency ventilation with a conventional ventilator allows reduction of tidal volume without increasing mean airway pressure. Intensive Care Medicine Experimental 2(1):13

Hardman J, Wills J (2006) The development of hypoxaemia during apnoea in children: a computational modelling investigation. British Journal of Anaesthesia 97(4):564–570

McCahon R, Columb M, Mahajan R, Hardman J (2008) Validation and application of a high-fidelity, computational model of acute respiratory distress syndrome to the examination of the indices of oxygenation at constant lung-state. British Journal of Anaesthesia 101(3):358–365

Hardman J, Bedforth N, Ahmed A, Mahajan R, Aitkenhead A (1998) A physiology simulator: validation of its respiratory components and its ability to predict the patient’s response to changes in mechanical ventilation. British Journal of Anaesthesia 81(3):327–332

Das A, Menon PP, Hardman JG, Bates DG (2013) Optimization of mechanical ventilator settings for pulmonary disease states. Biomedical Engineering, IEEE Transactions on 60(6):1599–1607

Wang W, Das A, Ali T, Cole O, Chikhani M, Haque M, Hardman JG, Bates DG (2014) Can computer simulators accurately represent the pathophysiology of individual COPD patients. Intensive Care Med Exp 2:23

Das A, Cole O, Chikhani M, Wang W, Ali T, Haque M, Bates DG, Hardman JG (2015) Evaluation of lung recruitment maneuvers in acute respiratory distress syndrome using computer simulation. Critical Care 19 (1):1–15

Nirmalan M, Willard T, Columb M, Nightingale P (2001) Effect of changes in arterial-mixed venous oxygen content difference (C (a–v̄) O2) on indices of pulmonary oxygen transfer in a model ARDS lung. British Journal of Anaesthesia 86(4):477–485

Golberg DE (1989) Genetic algorithms in search, optimization, and machine learning. Addison Wesley, Boston, MA, USA

West JB (2012) Respiratory physiology: the essentials. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, London

Ganong WF, Barrett KE (2005) Review of medical physiology, vol 21. McGraw-Hill Medical, New York

Force ADT (2012) Acute respiratory distress syndrome. JAMA 307(23):2526–2533

Chakrabarti M, Gordon G, Whitwam J (1986) Relationship between tidal volume and deadspace during high frequency ventilation. British Journal of Anaesthesia 58(1):11–17

Brogan TV, Thiagarajan RR, Rycus PT, Bartlett RH, Bratton SL (2009) Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in adults with severe respiratory failure: a multi-center database. Intensive Care Medicine 35(12):2105–2114

SUPERNOVA trial of ECCO2-R for moderate ARDS. http://www.esicm.org/research/trials-group/supernova. Accessed November 2015

Amato MB, Meade MO, Slutsky AS, Brochard L, Costa EL, Schoenfeld DA, Stewart TE, Briel M, Talmor D, Mercat A (2015) Driving pressure and survival in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. New England Journal of Medicine 372(8):747–755

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the UK Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EP/F057016/2, EP/F057059/1, EP/1036680/2) and Medical Research Council (G1002017, MR/K019783).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

WW, AD, MC, DGB and JGH designed the study; WW and AD implemented the computer simulations; and OC, MC and JGH contributed clinical data and protocols and evaluated the results of the study; all authors contributed to writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Simulation model description and optimisation algorithm description.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, W., Das, A., Cole, O. et al. Computational simulation indicates that moderately high-frequency ventilation can allow safe reduction of tidal volumes and airway pressures in ARDS patients. ICMx 3, 33 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40635-015-0068-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40635-015-0068-8