Abstract

Advancements in satellite altimetry have significantly enhanced high-resolution mean sea surface (MSS) models, enabling the computation of high-resolution vertical gravity anomaly gradient (VGAG) models. This study focused on the methodology for computing VGAG models using MSS models, introducing innovative improvements to established techniques. Using the SDUST2020 MSS model within the Arabian Sea research area, the DTU22 and CNES-CLS22 mean dynamic topography (MDT) models, and the XGM2019e_2159 Earth gravity field model for the remove–restore process, the short-wavelength geoid was derived. To harness the extensive marine gravity field information within the MSS model, the study considered the complex marine environment and calculated the second-order derivatives of the geoid in multiple directions. These derivatives were then used to determine their north–south and east–west components through the least squares method, resulting in the computation of the short-wavelength VGAG. By restoring the long-wavelength VGAG, a VGAG model for the study area was established. Finally, the results were analyzed using the SIO V32.1 VGAG model (named curv). Experimental results demonstrated that this approach effectively extracted marine gravity field information from the MSS model using multidirectional data, mitigating the amplification of geoid uncertainties caused by second-order derivatives.

Graphical Abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The development of high-resolution gravity field models is a substantial undertaking in the domain of physical geodesy, providing a foundational basis for the comprehensive exploration of the Earth’s subsurface properties (Barnes and Lumley 2011; Pajot et al. 2008). The achievement of this goal heavily depends on the accessibility of high-precision and high-resolution gravity and gravity gradient data (Sjöberg and Bagherbandi 2023).

Gravity gradient describes the variation of Earth’s gravity field in space, reflecting changes in both magnitude and direction. It is crucial for detecting subsurface structures and mass distribution variations (Mortimer 1977), playing a crucial role in geophysical exploration and marine gravity field studies (Butler 1984; Bouman et al. 2016).

The gravity gradient is typically represented by a tensor, which includes the partial derivatives of the gravity vector components in three spatial directions. In comparison to gravity anomaly, the vertical gravity anomaly gradient (VGAG) is valuable for its ability to enhance the visual representation of high-frequency information in the Earth’s gravity field. This enhanced visualization helps in depicting the spatial structure of field sources, the structural morphology of Earth’s interior, and determining the location and depth of density change structures more precisely (Romaides et al. 2001; Oruç 2011; Panet et al. 2014). Vertical gravity gradient (VGG) data are essential for detecting irregular density distributions beneath the Earth’s surface and for providing crucial information for investigating seafloor structures and refining the Earth’s gravity field.

As the utilization of gravity technology continues to grow and with rapid advancements in gravity field and gravity theory, there has been continual improvement in gravity gradient measurement technology (DiFrancesco et al. 2009; Stray et al. 2022; van der Meijde et al. 2015). The measurement of gravity gradients has transitioned from static to dynamic methods and expanded from ship-borne to aviation and space-borne platforms. In terms of measurement principles, it has diversified into various approaches, including torsion measurement, electrostatic levitation measurement, laser interferometry, atomic interferometry, superconducting measurement, and optical force inertial measurement. Measuring moving gravity gradients presents challenges in terms of requiring high-precision instruments and complex data processing, which hinder achieving global ocean coverage and incur significant costs. While the GOCE satellite, equipped with an electrostatic accelerometer gravity gradient instrument, provided global gravity data (Silvestrin et al. 2012; Rummel et al. 2011; Marks et al. 2013), its resolution was limited for delivering high-precision local gravity gradient data (Novák et al. 2013). Similarly, the GRACE satellite mission, though widely used for monitoring terrestrial water storage and studying large-scale mass redistribution (Rodell and Li 2023; Xu et al. 2023; Xiao et al. 2023), did not provide gravity gradient data, and its spatial resolution was insufficient for detailed local gravity field modeling. In contrast, satellite altimetry has matured and can provide global ocean gravity data (Andersen et al. 2016; Sandwell et al. 2021). Therefore, employing satellite altimetry data for ocean gravity inversion offers advantages in terms of computational efficiency and cost reduction, greatly enhancing the effectiveness and precision of ocean gravity observations.

Satellite altimetry technology was initially developed for studying global sea surface fluctuations and has since become a crucial tool for collecting ocean gravity data. The successful launch of an increasing number of altimetry satellites has enabled the acquisition of higher-precision satellite altimetry data. These data have significantly contributed to the investigation of global sea surface height (SSH) (Stanev and Peneva 2001; Jin and Li 2012), ocean gravity (Andersen et al. 2010; Sandwell et al. 2013; Zhu et al. 2022), ocean gravity gradient (Zhou et al. 2023; Rathnayake and Tenzer 2019), mean sea surface (MSS) (Pujol et al. 2018; Yuan et al. 2023; Andersen et al. 2021), seafloor topography (Yang et al. 2018; Hwang and Chang 2014), and ocean circulation (Guo et al. 2010; Zaron 2019).

The MSS is a parameter in the fields of geodesy and physical oceanography. It represents the steady-state relative sea level and is derived by averaging the instantaneous SSH data observed by satellite altimeters over a specific time period (Andersen and Knudsen 2009). In geodesy, the MSS serves as the reference datum for national elevation, while in oceanography, it acts as the reference datum for the ocean vertical. The MSS has various applications, including analyzing ocean circulation, detecting mesoscale eddies, evaluating changes in sea surface height, determining geoid fluctuations, and identifying crustal deformation (Fu and Cazenave 2001).

To explore the inversion methodology for VGAG using the MSS model, Sect. 2 of the study delineates the criteria for selecting the study area, MSS, and mean dynamic topography (MDT) models. Section 3 provides an exposition of the methodology devised to maximize the utilization of the extensive ocean gravity field information provided by the MSS model. Section 4 analyzes and evaluates the inversion model derived from the application of this method. Finally, in Sects. 5 and 6, the inversion method and results are discussed and summarized.

2 Study area and data sources

2.1 Study area

The study area selected encompassed the Arabian Sea and its surrounding areas, spanning from 0° N to 30°N and from 46° E to 79° E. The western portion of this region lay at the convergence of the Somali Plate, Indian Plate, and Arabian Plate, known for their dynamic geological features and frequent seismic activity. The central region was demarcated by the Carlsberg Ridge, which divided it into the Arabian Sea Basin and the Somali Basin. The eastern part of the study area was characterized by the Chagos-Laccadive Ridge, which surrounds the Laccadive Islands, Maldives, and Chagos Archipelago (Fig. 1).

The study area encompassed both geologically active ridge systems and stable basin structures. This composition enabled the effective validation of VGAG inversion results acquired from the MSS model under diverse topographic conditions, thereby guaranteeing the accuracy and reliability of the research outcomes.

2.2 Data sources

The SDUST2020 MSS model was selected as the research model. The SDUST2020 MSS model, developed by Shandong University of Science and Technology (Yuan et al. 2023), offered global coverage (80° S to 84° N) with a 1′ × 1′ resolution, based on data from 1993 to 2019. It uniquely integrated altimetry data from multiple satellites, including HY-2A, Jason-3, and Sentinel-3A, enhancing accuracy and reliability.

To obtain the geoid, the MDT model was subtracted from the MSS model. The DTU22 (Knudsen et al. 2022) and CNES-CLS22 (Jousset et al. 2022) MDT models were used in the study. The DTU22 MDT model excelled in providing precise geodetic measurements from satellite altimetry, enhancing the accuracy of mean dynamic topography determination. This precision aided in detailed geophysical analyses and marine gravity studies. The CNES-CLS22 MDT model integrated geodetic data with oceanographic information such as temperature, salinity profiles, and velocities from drifting buoys. This comprehensive approach enabled a more accurate and detailed understanding of ocean circulation and dynamic processes.

High-precision Earth gravity field models were crucial for applying the remove–restore method. The study selected the XGM2019e_2159 Earth gravity field model (Zingerle et al. 2020) for its superior accuracy and resolution. XGM2019e_2159 combined satellite data from missions like GRACE and GOCE with terrestrial measurements, providing a detailed and precise representation of the Earth’s gravity field. This model was fully expanded up to the 2159 order offering a resolution of approximately 5′. This degree of expansion was chosen because it optimized the model’s accuracy based on the available data, while further increasing the degree could introduce more errors rather than capturing meaningful geophysical signals. The high resolution of this model enhances geophysical and geodetic applications by enabling more accurate studies of ocean circulation, sea level changes, and geoid determination. Additionally, since it was difficult to obtain in situ measurements of VGAGs over the ocean, the study used the SIO V32.1 curv, which was also based on satellite altimetry data, to validate the proposed method. The SIO V32.1 dataset was a high-precision, high-resolution global ocean dataset that included models for the north–south and east–west components of deflection of the vertical, gravity anomalies, and vertical gravity anomaly gradients (VGAGs) (Garcia et al. 2014). The latest V32.1 version also included a MSS model.

The model’s publishing institution and resolution information are provided in Table 1.

3 Method

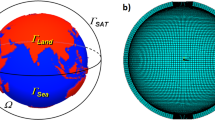

3.1 Principles of satellite altimetry

The principle of height measurement is illustrated in Fig. 2, and the process for extracting gravity information from remote sensing data is outlined as follows:

-

(1)

Satellite orbit determination: The first step is to accurately determine the satellite’s orbit height (\(H_{\text {alt}}\)). This involves calculating the satellite’s altitude relative to the Earth’s reference ellipsoid, which serves as the foundational data for satellite altimetry.

-

(2)

Instantaneous altimeter range measurement: The altimeter on the satellite measures the distance (\(H_{\text {range}}\)) from the satellite to the sea surface.

-

(3)

Calculation of instantaneous sea surface height (SSH): The instantaneous sea surface height is calculated by subtracting the measured distance from the satellite orbit height, resulting in the SSH.

-

(4)

Computation of MSS: By accumulating instantaneous sea surface height data over a long period, the MSS is computed, representing the long-term average position of the sea surface.

-

(5)

Removal of MDT: The mean sea surface includes both the geoid and the MDT. By using a MDT model, the influence of the MDT is removed from the MSS to obtain the geoid.

-

(6)

Derivation of geoid and gravity information: The geoid reflects variations in the Earth’s gravity field, and by analyzing the geoid, marine gravity field information can be inferred.

reproducted from Guo et al. (2022)

Schematic illustration of satellite altimetry and related measurements. This illustration displays the main components of satellite altimetry, including satellite altitude, SSH, MSS, SLA, geoid height, and MDT,

3.2 Vertical gravity gradient calculation

To facilitate calculations, the VGG is generally divided into the vertical normal gravity gradient and the VGAG. The normal gravity gradient refers to the rate of change of gravity with height under the assumption that the Earth is an ideal, uniformly ellipsoidal body. It is a function of latitude and is typically denoted as \(\frac{\partial \gamma }{\partial z}\). The calculation equation is:

where \(\gamma _\text{e}\) is the gravitational acceleration at the equator, \(\alpha\) is the Earth’s flattening, \(\omega\) is the Earth’s angular velocity, \(R_\text{e}\) is the Earth’s mean radius, and \(\varphi\) is the latitude. \(R_\text{e}\) is taken to be 6371008.8 m, which is the mean radius of the WGS84 reference ellipsoid.

The VGG represents the difference between the measured gravity gradient and the normal gravity gradient. This discrepancy is primarily due to the inhomogeneous distribution of mass within the Earth and variations in topography. The gravity anomaly gradient is particularly effective in characterizing the marine gravity field because it can reflect detailed information about seafloor topography and subsurface structures. This study places special emphasis on the calculation of the VGAG to more accurately describe and analyze the marine gravity field.

The connection between gravity anomaly (\(\Delta g\)) and disturbance potential (T) can be established through the basic equation of physical geodesy (Hofmann-Wellenhof and Moritz 2005):

where \(\Delta g\) is the gravity anomaly, T is the disturbance potential, and r is the distance from the center of the Earth. Differentiating with respect to r gives the VGAG:

Laplace’s equation \(\Delta T = 0\) and the Bruns formula \(T = N\gamma\) are introduced into Eq. (3):

where \(\gamma\) is the normal gravity at the point to be determined, R is the mean radius of the ellipsoid, N is the geoid, \(\varphi\) is the latitude, and \(\lambda\) is the longitude. Differential calculations were employed to effectively minimize the influence of long-wavelength errors (McAdoo et al. 2008). Equation (4) enables the representation of the VGAG using N, its first-order horizontal derivatives, and its second-order horizontal derivatives.

In data processing, to facilitate calculations, the MDT model with a resolution of 7.5′ × 7.5′ undergoes cubic spline interpolation to increase its resolution to 1′ × 1′. Subsequently, the interpolated MDT model is subtracted from the SDUST2020 MSS model to derive the geoid, N:

Following this, the remove–restore method is employed to subtract the XGM2019e_2159 geoid, denoted as \(N_{\text {ref}}\), from N, leading to the residual geoid, \(N_{\text {res}}\). The purpose of this is to eliminate the influence of long-wave signals during the calculation (Hwang 1999):

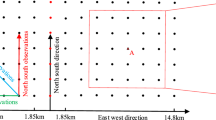

The MSS model, generally presented in a grid format with a resolution of 1′ × 1′, ensures consistency with the interpolated MDT model which has undergone cubic spline interpolation to match this resolution. To harness the rich oceanic information in the MSS model, the study selected the point to be determined as the center and established a calculation window. Data within this window were then utilized to calculate the second derivative of \(N_{\text {res}}\) from multiple directions.

The least squares method was employed to compute the north–south and east–west components of the second-order derivative of \(N_{\text {res}}\). This approach allowed for consideration of the intricate nature of ocean topography, optimizing the utilization of gravity field information within the model and ensuring precise and reliable results. The equation for the calculation is as follows:

where \(k\) is the number of equations, \(l\) denotes the horizontal distance between two points \(P\) and \(Q\), and \(a\) is the geodetic azimuth angle between these points. In this context, \(P\) and \(Q\) represent pairs of points used to calculate the second-order derivative at the center point of the calculation window. As illustrated in Fig. 3, each pair of points (\(P\) and \(Q\)) is aligned along a specific direction from the center point, allowing for a comprehensive directional derivative analysis.

For a calculation window of size \({i^{\prime}} \times {i^{\prime}}\), the number of equations \(k\) is determined using the equation \(k = \frac{i^2 - 1}{2}\). For instance, with a 5′ × 5′ window, there are 12 pairs of points \(P\) and \(Q\), resulting in 12 equations. These pairs are evenly distributed around the center point, each contributing to the overall calculation by providing a second-order derivative in a specific direction. This method considered the influence of the surrounding environment on the calculation point, thereby fully extracting the rich ocean gravity field information.

Equation (7) can be expressed in matrix form as:

where \(V\) represents the vector of residuals, \(A\) is the design matrix containing the coefficients (in this study, \(\cos ^2 \alpha _{kP,kQ}\), \(2 \sin \alpha _{kP,kQ} \cos \alpha _{kP,kQ}\), and \(\sin ^2 \alpha _{kP,kQ}\)), \(X\) is a vector of three components representing the second-order derivatives of the residual geoid in the north–south, east–west directions, and their mixed partial derivative, and \(L\) is the vector of observations representing the second-order derivatives of the residual geoid in the direction along the line connecting points \(P\) and \(Q\).

The matrix \(A\) can be written as:

where each row corresponds to the directional cosines of the angle \(a_{kP,kQ}\) between the \(k\)th line segment and the coordinate axes, as well as the interaction between the directions.

By minimizing the cost function \(\phi = V^{\text{T}} W V\), \(X\) is determined as:

where the weight matrix \(W\) is determined using the reciprocal of the square of the distance to the point to be determined. This solution provides the best estimate of the second-order derivatives of the residual geoid in the north–south, east–west directions, and their interaction terms, which are essential for the computation of the residual VGAG, represented as \(\frac{\partial \Delta g}{\partial r}_{\text{res}}\).

Subsequently, the remove–restore method was applied to restore the XGM2019e_2159 VGAG, leading to the development of a VGAG model:

where \(\frac{\partial \Delta g}{\partial r}_{\text {res}}\) represents the residual VGAG, obtained from Eq. (10).

In contrast to this study, which calculated the VGG by utilizing the horizontal second derivatives of the geoid, the VGAG model, named ‘curv’ in the SIO V32.1 database, is computed from the first-order derivatives of the deflection of the vertical in the north–south and east–west components (Muhammad et al. 2010; Sandwell and Smith 1997, 2009). To assess and validate the correctness of the method proposed in this study, the results were compared with the SIO V32.1 curv.

The study’s workflow is depicted in Fig. 4.

4 Results and analysis

The study utilized the SDUST2020 MSS model along with the DTU22 MDT and CNES-CLS22 MDT models to validate the accuracy of the methodology. The DTU22 MDT and CNES-CLS22 MDT models were employed to remove the influence of mean dynamic topography (MDT) from the SDUST2020 mean sea surface (MSS) model, thereby obtaining the geoid. By using one MSS model and two MDT models, the results were cross-verified using different MDT models, ensuring the robustness and reliability of the approach.

To preserve the high-frequency information in the mean sea surface (MSS) model, filtering techniques such as Gaussian filtering were not applied. This approach ensures that all relevant features are retained, which is crucial for the accuracy of the methodology.

Additionally, to further mitigate the impact of long-wavelength signals on the calculations, the remove–restore method was employed to determine the residual geoid.

Calculation windows were defined with the point to be determined as the center. The data within these windows, which were the geoid heights at the surrounding grid points, were used to compute the second-order derivatives of the residual geoid. These geoid heights were then utilized in the least squares method to calculate the north–south and east–west components of the second-order derivatives at the point to be determined. Following the completion of the experiment in Sect. 5.1, the optimal size of the window was determined to be 17′ × 17′.

The residual VGAG (short-wavelength) was computed by substituting the two obtained components into Eq. (4). After restoring the XGM2019e_2159 VGAG (long-wavelength), the study developed a 1′ × 1′ VGAG model for the study area. In Fig. 5, Model a is derived from SDUST2020 MSS and DTU22 MDT, while Model b is derived from SDUST2020 MSS and CNES-CLS22 MDT.

The VGAG model, depicted in Fig. 5, shows a noticeable correlation between the VGAG and seafloor topography and structure. This model not only reflects the variation in seafloor topography but also reveals the underlying tectonic processes that govern these features. Particularly, the VGAG variations correspond closely with tectonic features such as fracture zones and ridges, which are indicative of the stress and strain within the Earth’s crust caused by tectonic movements. In this study, various geological regions within the research area were selected for in-depth analysis.

In the region from 12.5° N, 50° E to 1° N, 70° E, notable geological features were found, such as the West-Sheba Ridge, East-Sheba Ridge, and Carlsberg Ridge. These features are characterized by significant VGAGs, which are a direct result of tectonic forces acting upon the Earth’s crust. The alternating positive and negative VGAGs along these ridges suggest zones of varying crustal density, likely due to the presence of fault lines where lower-density material fills the voids created by tectonic activity. These variations in VGAGs could indicate a dynamic tectonic environment in this region, where extensional forces along the ridges might be creating areas of crustal thinning, leading to the formation of grabens and horsts. The observed negative VGAGs in the central parts of these ridges might be associated with subsided blocks within the rifted zones, suggesting the influence of tectonic stress on the crustal architecture. Such patterns appear to highlight the complex interplay between tectonic forces and crustal composition.

Likewise, in the area spanning from 10° N, 57° E to 25° N, 66° E, encompassing the Murray Ridge and Owen Fracture-Zone, parallel zones of positive and negative VGAGs were discernible. This pattern suggests significant tectonic compression, where crustal stress has likely resulted in differential movement of crustal blocks. The positive VGAGs appear to be linked to uplifted blocks, while the negative VGAGs may correspond to subsided regions, reflecting the possible active tectonics in this area. The Owen Fracture-Zone, which is thought to be a major transform fault boundary, could be acting as a critical zone of lithospheric deformation, where lateral movement between the Indian and Arabian plates may have generated significant crustal strain. This strain likely manifests as varying VGAGs along the fracture zone, suggesting the influence of tectonic forces driving crustal deformation, causing one side of the crust to rise while the other side sinks (Fournier et al. 2011).

Additionally, within the Chagos-Laccadive Ridge area, ranging from 0.5° N, 73.8° E to 14° N, 74° E, noticeable variations in the VGAGs were apparent. The VGAG patterns here suggest a complex interplay of tectonic forces, with the ridge being intersected by several fractures that could potentially result in fragmented VGAGs. In the central portion of the southern Maldive Ridge, positive values of the VGAGs are predominant, while around the sea platform, negative values of the VGAGs prevail.

The analysis utilized VGAG model derived from satellite altimetry. In specific regions such as coastal waters, ridges, and continental shelves, pronounced variations in gravity anomalies were observed, leading to larger absolute values of VGAGs. This was determined by examining the spatial distribution and magnitude of VGAGs across different geological features. These areas exhibit significant changes in gravity anomalies due to varying crustal thickness and subsurface structures. Conversely, in geologically stable ocean basins, the absolute values of VGAGs tend to approach zero. The analysis indicated that gravity anomalies in these regions change more gradually, with smaller variations in crustal thickness and simpler subsurface structures.

The study utilized the SIO V32.1 curv model to validate the consistency of the proposed inversion method. Two sets of residual models were generated by subtracting the SIO V32.1 curv model from Model a and Model b, respectively. These residual models, along with their respective histograms, are illustrated in Figs. 6 and 7. Table 2 presents the statistical analysis of the residual models.

Histogram of the residual VGAG model derived from the SDUST2020 MSS model. a Histogram of residual VGAG inverted using the DTU22 MDT. b Histogram of residual VGAG inverted using the CNES-CLS22 MDT. The fitted normal distributions indicate the mean (\(\mu\)) and standard deviation (\(\sigma\)) for each model

As shown in Fig. 7, a close match indicates that the inversion method produces consistent results with the SIO V32.1 curv model. The diagrams referred to above illustrate the distribution differences between the VGAG model obtained from the inversion of the SDUST2020 MSS model and the SIO V32.1 curv model. In the offshore basin area, the residual model exhibits relatively small absolute magnitudes. However, in specific terrains such as nearshore areas and the regions encompassing the Carlsberg Ridge, Owen Fracture-Zone, Chagos-Laccadive Ridge, and Murray Ridge, the absolute values are considerably larger, with the greatest difference exceeding 300 E. Residuals in the Chagos-Laccadive Ridge and coastal areas exhibit notably larger absolute values than other regions. This contrast can be attributed to the elevation of the southern segment of the Chagos-Laccadive Ridge above sea level, displaying nearshore characteristics (Kunnummal and Anand 2019; Verzhbitsky 2003). The significant differences in these complex terrains are likely due to the lower quality of altimetry data, which affects the consistency of the inversion results in such regions.

Furthermore, the VGAG_Res_a and VGAG_Res_b models exhibit some similarities, and their residuals conform to a normal distribution, with values ranging from − 20 E to 20 E, accounting for approximately 99% of the total distribution.

Notably, when the CNES-CLS22 MDT is employed as the subtracting model, the inversion results show a slightly higher standard deviation of error compared to using the DTU22 MDT. This discrepancy can be attributed to the fact that the DTU22 MDT utilizes the XGM2019e_2159 reference gravity field for geoid computation, whereas the CNES-CLS22 MDT relies on the GOCO06S gravity field model. As a result, there is a stronger correlation between the SDUST2020 MSS and the DTU22 MDT.

5 Discussion

5.1 Calculation window

The size of the calculation window determines the amount of data used in the inversion process. It was observed during the study that the window size has a significant impact on the inversion results. Smaller windows may not capture enough data to fully utilize the method’s advantages, while larger windows, although covering more data, do not significantly improve accuracy and may negatively impact computational efficiency. The optimal window size was determined by achieving the best consistency with the SIO V32.1 model. The statistical data for the residual Model a and SIO V32.1 can be found in Table 3.

Table 3 presents the statistics of the residual vertical gravity anomaly gradient model for different calculation window sizes. As the window size increases, both the maximum and minimum values stabilize. For smaller windows, such as 3′ × 3′, the range between the maximum (424.99 E) and minimum (− 422.76 E) values is broader, while for larger windows, such as 17′ × 17′, this range narrows. This indicates that larger windows smooth extreme anomaly values. The mean values remain close to zero across all window sizes, suggesting that the inversion process is unbiased.

The standard deviation decreases with increasing window size, from 17.07 E at 3′ × 3′ to 7.76 E at 17′ × 17′, indicating that larger windows lead to more consistent results. However, further increases in window size beyond 17′ × 17′ yield minimal reductions in standard deviation. In contrast, the computational time increases significantly with window size, from 375 s for the 3′ × 3′ window to 1765 s for the 17′ × 17′ window, and 2439 s for the 21′ × 21′ window. This reflects a super-linear increase in computational complexity with larger window sizes. Thus, while larger windows marginally improve data smoothing, the increased computational cost suggests that selecting an optimal window size is essential for balancing accuracy and efficiency.

5.2 Analysis of residual model

The examination of intricate geological formations, such as seamounts and fault zones, within the residual models revealed a noteworthy relationship between topography, geomorphology, and VGAG. To delve deeper into the factors influencing the inversion outcomes, a statistical analysis was performed on data obtained at different distances from the coast and islands. The findings of this analysis are outlined in Table 4.

Table 4 provides clear insights into the relationship between offshore distance and the STD of the residual model. Notably, as the distance from the coastline increases, the STD of the residual model consistently decreases. It’s important to highlight that beyond a distance of 50 km from the coastline, the rate of STD reduction begins to slow down. This phenomenon can be attributed to the fact that satellite echo waveforms are progressively less influenced by the shallow water areas in the coastal zone, resulting in relatively modest improvements in satellite data accuracy. In summary, proximity to the coastline corresponds to a larger STD in the residual model, while offshore areas, farther from the coastline, exhibit lower STD values. The points with larger absolute values in the residual model are primarily concentrated in nearshore and shallow water regions.

To further investigate the influence of water depth on the inverted VGAG model, the study calculated the differences in the residual model at different depths, as presented in Table 5.

Table 5 provides a clear depiction of how the STD of the residual model varies with different depths. It is noteworthy that when the water depth is less than 1 km, the STD of the residual model reaches its highest point. Conversely, the STD of the residual model exhibits a consistent decrease as water depth increases. This trend can be attributed to the fact that points with shallower water depths are predominantly situated near the coastline, ridges, and seamounts, where the structure is notably more complex. Conversely, points with relatively greater water depths are primarily located near basins, where the seafloor structure is considerably smoother. This observation underscores the influence of seafloor topography on the inversion results.

To delve deeper into the impact of seafloor topographic variations on VGAG inversion results, the study employed SIO topo_25.1 model to calculate seafloor slopes within the study area. Subsequently, the residual model was analyzed at different seafloor slopes.

Table 6 provides noteworthy insights into the relationship between seafloor slope and the STD of the residual model. It is evident that points with a slope of less than 1% constitute a significant majority, accounting for 54.22% of the total data points. Interestingly, as the seafloor slope increases, the STD of the residual model also displays an increasing trend, though there is no discernible pattern for the extreme values. This observation suggests that in areas characterized by relatively smooth seafloor topography, the STD of the residual model tends to be smaller. In contrast, in regions with complex seafloor topography, the STD is notably larger.

Consequently, it can be inferred that underwater structure exerts a notable impact on the inversion results, resulting in greater discrepancies between the two models in areas with more intricate underwater anomaly structures. Given that both the VGAG model generated in this study and the SIO V32.1 model are derived from altimetry data, it is understood that variations in altimetry data quality due to topographic factors contribute to the observed differences in model consistency. Areas with complex topography tend to exhibit lower altimetry data quality and, consequently, greater discrepancies between the two models, while regions with higher altimetry data quality show greater consistency between the models.

6 Conclusion

This study proposed a novel method for modeling VGAGs by combining multidirectional MSS data with the least squares approach. The Arabian Sea and its adjacent areas were selected as the study region. The SDUST2020 MSS model was employed to calculate the geoid by subtracting the MDT model. Subsequently, the remove–restore method was applied to eliminate the long-wavelength signals calculated by the XGM2019e_2159 model, followed by the restoration of the long-wavelength signals after computing the short-wavelength VGAG, resulting in the construction of a VGAG model for the study area. This optimized the calculation process and enhanced the reliability of the inversion.

Analysis of the inversion model indicated that regions with larger absolute values of VGAGs, such as coastal areas, the Carlsberg Ridge, the Owen Fracture-Zone, the Chagos-Laccadive region, and the Murray Ridge, display significant slope variations and complex geological structures. Conversely, regions with smaller VGAG absolute values, such as the Arabian Sea Basin, exhibit relatively gradual changes in surface materials and moderate topographic slopes, resulting in minor variations in crustal density.

The MSS model generated from satellite altimetry data retains the characteristics of altimetric data. Comparison of the inversion results of Model a with the SIO V32.1 curv model revealed that in areas near the coastline and with complex topography, the quality of satellite data is affected, leading to poorer consistency between the two models. In contrast, in regions with flat seafloor structures and no island chains, the consistency between the two models is better.

The amount of data available for VGAG inversion using multidirectional MSS is determined by the size of the calculation window. Through an analysis of the impact of calculation window size on the inversion results, the study identified that a 17′ × 17′ window size is optimal. Comparison with the SIO V32.1 curv revealed that Model a had an average error of − 0.00 E and a standard deviation of 7.76 E, confirming the validity of the proposed method. The use of a 17′ × 17′ window size effectively considered the influence of the surrounding environment on the central calculation point. The least squares method maximized the reduction of residuals, and the multidirectional data approach effectively suppressed the amplification of geoid uncertainties caused by second-order derivatives.

Availability of data and materials

The SDUST2020 MSS model is available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6555990. The DTU22 MDT can be accessed at https://ftp.space.dtu.dk/pub/DTU22/MDT/dtu22mdt.xyz.gz. The CNES-CLS22 MDT is available at https://www.aviso.altimetry.fr/en/data/products/auxiliary-products/mdt/mdt-global-cnes-cls.html. The XGM2019e_2159 Earth gravity field model can be obtained from http://icgem.gfz-potsdam.de/tom_longtime. The SIO V32.1 database is accessible at https://topex.ucsd.edu/pub/global_grav_1min/.

Abbreviations

- MSS:

-

Mean sea surface

- VGG:

-

Vertical gravity gradient

- VGAG:

-

Vertical gravity anomaly gradient

- MDT:

-

Mean dynamic topography

- SSH:

-

Sea surface height

References

Andersen OB, Knudsen P (2009) DNSC08 mean sea surface and mean dynamic topography models. J Geophys Res Oceans 114:C11001. https://doi.org/10.1029/2008JC005179

Andersen OB, Knudsen P, Berry PAM (2010) The DNSC08GRA global marine gravity field from double retracked satellite altimetry. J Geod 84(3):191–199. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00190-009-0355-9

Andersen OB, Jain M, Knudsen P (2016) The impact of using Jason-1 and Cryosat-2 geodetic mission altimetry for gravity field modeling. In: Rizos C, Willis P (eds) IAG 150 years. Springer, Cham, pp 205–210

Andersen OB, Abulaitijiang A, Zhang S, Rose SK (2021) A new high resolution Mean Sea Surface (DTU21MSS) for improved sea level monitoring. EGU General Assembly 2021, online, Abstract ID: EGU21-16084

Butler DK (1984) Microgravimetric and gravity gradient techniques for detection of subsurface cavities. Geophysics 49(7):1084–1096. https://doi.org/10.1190/1.1441723

Barnes G, Lumley J (2011) Processing gravity gradient data. Geophysics 76(2):I33–I47. https://doi.org/10.1190/1.3548548

Bouman J, Ebbing J, Fuchs M, Sebera J, Lieb V, Szwillus W, Haagmans R, Novak P (2016) Satellite gravity gradient grids for geophysics. Sci Rep 6:21050. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep21050

DiFrancesco D, Grierson A, Kaputa D, Meyer T (2009) Gravity gradiometer systems—advances and challenges. Geophys Prospect 57(4):615–623. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2478.2008.00764.x

Fournier M, Chamot-Rooke N, Rodriguez M, Huchon P, Petit C, Beslier MO, Zaragosi S (2011) Owen fracture zone: the Arabia-India plate boundary unveiled. Earth Planet Sci Lett 302(1):247–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2010.12.027

Fu LL, Cazenave A (2001) Satellite altimetry and earth sciences: a handbook of techniques and applications. Academic Press, London

Garcia ES, Sandwell DT, Smith WHF (2014) Retracking CryoSat-2, Envisat and Jason-1 radar altimetry waveforms for improved gravity field recovery. Geophys J Int 196(3):1402–1422. https://doi.org/10.1093/gji/ggt469

Guo J, Chang X, Hwang C, Sun J, Han Y (2010) Oceanic surface geostrophic velocities determined with satellite altimetric crossover method. Chin J Geophys 53(6):926–934. https://doi.org/10.1002/cjg2.1563

Guo J, Luo H, Zhu C, Ji H, Li G, Liu X (2022) Accuracy comparison of marine gravity derived from HY-2A/GM and CryoSat-2 altimetry data: a case study in the Gulf of Mexico. Geophys J Int 230(2):1267–1279. https://doi.org/10.1093/gji/ggac114

Hofmann-Wellenhof B, Moritz H (2005) Physical geodesy. Springer, New York

Hwang C (1999) A bathymetric model for the South China Sea from satellite altimetry and depth data. Mar Geod 22(1):37–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/014904199273597

Hwang C, Chang ETY (2014) Seafloor secrets revealed. Science 346(6205):32–33. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1260459

Jin T, Li J (2012) Correction of tidal gauge observations for linear drift in mean sea surface height using tidal gauge data. Geomat Inf Sci Wuhan Univ 37(10):1194–1197. https://doi.org/10.13203/j.whugis2012.10.020

Jousset S, Mulet S, Wilkin J, Greiner E, Dibarboure G, Picot N (2022) New global mean dynamic topography CNES-CLS-22 combining drifters, hydrological profiles and high frequency radar data. OSTST. https://doi.org/10.24400/527896/a03-2022.3292

Knudsen P, Andersen OB, Maximenko N, Hafner J (2022) A new combined mean dynamic topography model—DTUUH22MDT. In: Proceedings of the living planet symposium, Bonn, Germany, pp 23–27

Kunnummal P, Anand SP (2019) Qualitative appraisal of high resolution satellite derived free air gravity anomalies over the Maldive Ridge and adjoining ocean basins, western Indian Ocean. J Asian Earth Sci 169:199–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jseaes.2018.08.008

Marks KM, Smith WHF, Sandwell DT (2013) Significant improvements in marine gravity from ongoing satellite missions. Mar Geophys Res 34(2):137–146. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11001-013-9190-8

McAdoo DC, Farrell SL, Laxon SW, Zwally HJ, Yi D, Ridout AL (2008) Arctic Ocean gravity field derived from ICESat and ERS-2 altimetry: tectonic implications. J Geophys Res Solid Earth 113:B05408. https://doi.org/10.1029/2007JB005217

Mortimer Z (1977) Gravity vertical gradient measurements for the detection of small geologic and anthropogenic forms; discussion. Geophysics 42(7):1484–1485. https://doi.org/10.1190/1.1440812

Muhammad S, Zulfiqar A, Ayub M (2010) Vertical gravity anomaly gradient effect of innermost zone on geoid-quasigeoid separation and an optimal integration radius in planar approximation. Appl Geomat 2(1):9–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12518-010-0015-z

Novák P, Tenzer R, Eshagh M, Bagherbandi M (2013) Evaluation of gravitational gradients generated by Earth’s crustal structures. Comput Geosci 51:22–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cageo.2012.08.006

Oruç B (2011) Edge detection and depth estimation using a tilt angle map from gravity gradient data of the Kozaklı-Central Anatolia region, Turkey. Pure Appl Geophys 168:1769–1780. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00024-010-0211-0

Pajot G, de Viron O, Diament M, Lequentrec-Lalancette MF, Mikhailov V (2008) Noise reduction through joint processing of gravity and gravity gradient data. Geophysics 73(3):I23–I34. https://doi.org/10.1190/1.2905222

Panet I, Pajot-Metivier G, Greff-Lefftz M, Metivier L, Diament M, Mandea M (2014) Mapping the mass distribution of Earth’s mantle using satellite-derived gravity gradients. Nat Geosci 7(2):131–135. https://doi.org/10.1038/NGEO2063

Pujol M-I, Schaeffer P, Faugère Y, Raynal M, Dibarboure G, Picot N (2018) Gauging the improvement of recent mean sea surface models: a new approach for identifying and quantifying their errors. J Geophys Res Oceans 123(8):5889–5911. https://doi.org/10.1029/2017JC013503

Rathnayake S, Tenzer R (2019) Interpretation of the lithospheric structure beneath the Indian Ocean from gravity gradient data. J Asian Earth Sci 183:103934. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jseaes.2019.103934

Romaides AJ, Battis JC, Sands RW, Zorn A, Benson DO Jr, DiFrancesco DJ (2001) A comparison of gravimetric techniques for measuring subsurface void signals. J Phys D Appl Phys 34(3):433–443. https://doi.org/10.1088/0022-3727/34/3/331

Rodell M, Li B (2023) Changing intensity of hydroclimatic extreme events revealed by GRACE and GRACE-FO. Nat Water 1(3):241–248. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44221-023-00040-5

Rummel R, Yi W, Stummer C (2011) GOCE gravitational gradiometry. J Geod 85:777–790. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00190-011-0500-0

Sandwell DT, Smith WHF (1997) Marine gravity anomaly from Geosat and ERS 1 satellite altimetry. J Geophys Res Solid Earth 102(B5):10039–10054. https://doi.org/10.1029/96JB03223

Sandwell DT, Smith WHF (2009) Global marine gravity from retracked Geosat and ERS-1 altimetry: ridge segmentation versus spreading rate. J Geophys Res Solid Earth 114:B011411. https://doi.org/10.1029/2008JB006008

Sandwell DT, Garcia ESM, Soofi K, Wessel P, Chandler M, Smith WHF (2013) Toward 1-mGal accuracy in global marine gravity from CryoSat-2, Envisat, and Jason-1. Lead Edge 32(8):892–899. https://doi.org/10.1190/tle32080892.1

Sandwell DT, Harper H, Tozer B, Smith WHF (2021) Gravity field recovery from geodetic altimeter missions. Adv Space Res 68(2):1059–1072. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asr.2019.09.011

Silvestrin P, Aguirre M, Massotti L, Leone B, Cesare S, Kern M, Haagmans R (2012) The future of satellite gravimetry after the GOCE mission. Geodesy for planet earth. Springer, Berlin, pp 223–230

Sjöberg LE, Bagherbandi M (2023) Theory and applications of the Earth’s gravity field. Encyclopedia of earth sciences series. Springer, New York

Stanev EV, Peneva EL (2001) Regional sea level response to global climatic change: Black Sea examples. Glob Planet Change 32(1):33–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0921-8181(01)00148-5

Stray B, Lamb A, Kaushik A, Vovrosh J, Rodgers A, Winch J, Hayati F, Boddice D, Stabrawa A, Niggebaum A, Langlois M, Lien Y-H, Lellouch S, Roshanmanesh S, Ridley K, de Villiers G, Brown G, Cross T, Tuckwell G, Faramarzi A, Metje N, Bongs K, Holynski M (2022) Quantum sensing for gravity cartography. Nature 602(7898):590–594. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-04315-3

van der Meijde M, Pail R, Bingham R, Floberghagen R (2015) GOCE data, models, and applications: a review. Int J Appl Earth Obs Geoinf 35(A):4–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jag.2013.10.001

Verzhbitsky EV (2003) Geothermal regime and genesis of the Ninety-East and Chagos-Laccadive ridges. J Geodyn 35(3):289–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0264-3707(02)00068-6

Wessel P, Luis JF, Uieda L, Scharroo R, Wobbe F, Smith WHF, Tian D (2019) The generic mapping tools version 6. Geochem Geophys Geosyst 20(11):5556–5564. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019GC008515

Xiao C, Zhong Y, Feng W, Gao W, Wang Z, Zhong M, Ji B (2023) Monitoring the catastrophic flood with GRACE-FO and near-real-time precipitation data in northern Henan Province of China in July 2021. IEEE J Sel Top Appl Earth Obs Remote Sens 16:89–101. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSTARS.2022.3223790

Xu G, Wu Y, Liu S, Cheng S, Zhang Y, Pan Y, Wang L, Dokuchits EY, Nkwazema OC (2023) How 2022 extreme drought influences the spatiotemporal variations of terrestrial water storage in the Yangtze River Catchment: insights from GRACE-based drought severity index and in-situ measurements. J Hydrol 626:130245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2023.130245

Yang J, Jekeli C, Liu L (2018) Seafloor topography estimation from gravity gradients using simulated annealing. J Geophys Res Solid Earth 123(8):6958–6975. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018jb015883

Yuan J, Guo J, Zhu C, Li Z, Liu X, Gao J (2023) SDUST2020 MSS: a global 1′ × 1′ mean sea surface model determined from multi-satellite altimetry data. Earth Syst Sci Data 15(1):155–169. https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-15-155-2023

Zaron E (2019) Simultaneous estimation of ocean tides and under-water topography in the Weddell Sea. J Geophys Res Oceans 124(5):3125–3148. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019JC015037

Zhou R, Liu X, Li Z, Sun Y, Yuan J, Guo J, Ardalan A (2023) On performance of vertical gravity gradient determined from CryoSat-2 altimeter data over Arabian Sea. Geophys J Int 234(2):1519–1529. https://doi.org/10.1093/gji/ggad153

Zhu C, Guo J, Yuan J, Li Z, Liu X, Gao J (2022) SDUST2021GRA: global marine gravity anomaly model recovered from Ka-band and Ku-band satellite altimeter data. Earth Syst Sci Data 14:4589–4606. https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-14-4589-2022

Zingerle P, Pail R, Gruber T, Oikonomidou X (2020) The combined global gravity field model XGM2019e. J Geod 94(7):66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00190-020-01398-0

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to DTU, CNES, TUM, and SIO for their open policy. They also express gratitude for the invaluable feedback provided by the reviewers on this work. Figures in this study were extensively generated using the Generic Mapping Tools (GMT) (Wessel et al. 2019).

Funding

This study received support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 42274006, 42192535, 41774001, and 42430101).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The study and algorithm development were designed by Guo, Zhou, and Liu. Data analysis was conducted by Hwang, Guo, Jia, Chang, and Sun. Zhou authored the manuscript with contributions from Guo and Hwang. All authors actively participated in theoretical considerations, discussions, and manuscript preparation. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing financial or non-financial interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, R., Liu, X., Guo, J. et al. Inverting vertical gravity anomaly gradients using multidirectional data from a mean sea surface model: the case of the Arabian Sea. Earth Planets Space 76, 170 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40623-024-02105-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40623-024-02105-5