Abstract

Cellulosic ethanol is one of the most important biotechnological products to mitigate the consumption of fossil fuels and to increase the use of renewable resources for fuels and chemicals. By performing this process at high total solids (TS) and low enzyme loadings (EL), one can achieve significant improvements in the overall cellulosic ethanol production process. In this work, steam-exploded materials were obtained from Eucalyptus urograndis chips and sugarcane bagasse to be subsequently used for enzymatic hydrolysis at high TS (20 wt%) and relatively low EL (13.3 FPU g−1 TS of Cellic CTec3 from Novozymes). Also, the fermentability of their corresponding hydrolysates was tested using an industrial strain of Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Thermosacc Dry from Lallemand). Enzymatic hydrolysis of steam-treated E. urograndis reached 125 g L−1 of glucose in 72 h, while steam-treated bagasse gave yields 25 % lower. Both substrate hydrolysates were easily converted to ethanol, giving yields above 25 g L−1 and productivities of 2.3 g L−1 h−1 for eucalypt and 2.2 g L−1 h−1 for bagasse after only 12 h of fermentation. Under the conditions used in this study, sugarcane bagasse glucans showed the potential to boost the ethanol production from sugarcane culms by 31 %, from the 80 L t−1 of first generation to a total production of 105 L t−1. On the other hand, E. urograndis plantations are able to achieve cellulosic ethanol productivities of 2832.2 L ha−1 year−1, which was 57.8 % higher than the projected value of 1794.5 L ha−1 year−1 that was obtained for sugarcane bagasse.

Cellulosic ethanol was produced from steam-exploded substrates that were derived from Eucalyptus urograndis chips and sugarcane bagasse using high total solids and low enzyme loadings

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Cellulosic ethanol is currently produced by fermentation of carbohydrates that are released from plant polysaccharides by enzymatic hydrolysis. Such production process depends on five sequential steps involving: (1) collection and preparation of plant biomass; (2) pretreatment for increasing the susceptibility of plant polysaccharides to bioconversion at high process yields; (3) enzymatic hydrolysis for converting plant polysaccharides into fermentable sugars; (4) microbial fermentation for cellulosic ethanol production; and, finally, (5) the recovery of ethanol by distillation [1–3].

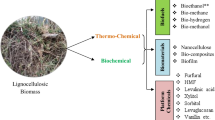

Several agro-industrial and forestry residues are of great interest as feedstocks for cellulosic ethanol production, such as in the case of sugarcane bagasse and short rotation clones of Eucalyptus sp., respectively [4]. Brazil produced 659 million tons of sugarcane in the 2014/2015 harvest season and this resulted in the accumulation of 92 million tons of sugarcane bagasse (14 % on dry basis) after its processing for sucrose and/or first generation ethanol [5, 6]. Most of this bagasse is currently used for energy purposes but there is a surplus that still represents a great opportunity for the development of sustainable biorefineries. On the other hand, over 55 % of the world eucalypt production is located in South America [7] and Brazil has an important role as a world leader in the production of short fibers for pulp and paper, mostly from Eucalyptus urograndis, E. saligna and E. urophylla [8]. In addition, other species of Eucalyptus sp. and some of their hybrids have shown great potential for the development of bioenergy projects such as clones of E. urograndis that have fast growth rates and high wood density [9, 10]. Hence, the availability and favorable properties of these lignocellulosic materials has motivated a great interest in their use for the production of cellulosic ethanol and other important building blocks for the chemical industry, as well as composites and structural materials in both nano and fiber scales [11–13]. Besides, biomass upgrading to fuels, chemicals and materials offers no immediate risks to food security issues.

Steam explosion is one of the most widely used pretreatment method for cellulosic ethanol production [14–16]. This method increases the accessibility of cellulose by deconstructing the associative structure of the plant cell wall, causing an increase in the substrate surface area and pore volume. Changes are also introduced into the biomass chemistry, particularly by acid hydrolysis and partial dissolution of hemicelluloses and lignin [17, 18]. However, pretreatment conditions must be optimized to avoid undesirable side reactions such as carbohydrate dehydration and lignin condensation.

Enzymatic hydrolysis is accomplished by different classes of enzymes which are intended to convert all of the available plant polysaccharides into fermentable sugars. According to Wingren et al. [19], an increase of substrate total solids (TS) from 5 to 8 wt% can reduce the cellulosic ethanol production cost by 20 %. Hence, by performing this step at high TS and low enzyme loadings (EL), it is possible to achieve significant improvements in the economics of the overall cellulosic ethanol production process. These improvements involve a better integration of process streams, energy savings and reductions in capital cost for hydrolysis and distillation, particularly coming from the fact that high sugar concentrations are produced for fermentation [2, 20–22].

Different process configurations have been developed so far for cellulosic ethanol production. If fermentation is carried out after enzymatic hydrolysis using substrate hydrolysates that were filtered to remove suspended solids, the process configuration is referred to as separate hydrolysis and fermentation (SHF). The advantages of SHF are that both steps can be carried out at their optimal conditions and yeast recycling is perfectly feasible, but the capital cost is higher and enzymatic hydrolysis is limited by end-product inhibition. Ethanol can also be produced by simultaneous saccharification and fermentation (SSF) and, in this case, the capital cost is lower, the total processing time is reduced and end-product inhibition is alleviated because sugars are fermented as they are produced by the concerted action of the enzymes. However, SSF does not allow yeast recycling and hydrolysis is usually carried out below its optimal temperature. In both configurations mentioned above, ethanol yields can be increased if the fermenting organism is able to convert pentoses and hexoses simultaneously [23, 24].

This work compares the efficiency of steam explosion in producing cellulosic ethanol at high TS and relatively low EL from two different lignocellulosic materials. Wood chips of E. urograndis and sugarcane bagasse were used for this purpose and ethanol was produced by SHF because we aimed to assess cellulose accessibility without the inhibitory effect of pretreatment water solubles.

Results and discussion

Chemical analysis and pretreatment by steam explosion

As expected, differences were observed in the chemical composition of both native sugarcane bagasse and E. urograndis chips (Table 1) and these were in good agreement with the general knowledge about the compositional analysis of both grasses [16, 17, 25] and hardwoods [5, 26]. In general, sugarcane bagasse presented lower glucan and lignin contents while its total extractives, pentosan and ash contents were much higher than those of E. urograndis wood chips. Both eucalypt and sugarcane bagasse hemicelluloses were partially quantified as xylans because the High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) method used for analysis was not able to quantify uronic acids and to resolve xylose, galactose and mannose in biomass acid hydrolysates. The extractives content was generally higher for sugarcane bagasse due to the presence of larger quantities of waxes, cinnamic acid derivatives, terpenes, lipids and other extractable materials [25, 27]. On the other hand, the high ash content of sugarcane bagasse may be partially due to unavoidable contaminations with soil, which are due to the current mechanical harvesting techniques. Biogenic ashes usually contain variable amounts of alkaline and alkaline earth oxides that are easily leached out by a mild acid treatment. Hence, the buffering capacity of this acid leaching may partially compromise the efficiency of pretreatment methods that rely on acid hydrolysis. However, the buffering capacity of sugarcane bagasse is not very high because basic oxides do not account for more than 7 % of its total ash content [25].

The pretreatment mass recovery yields were similar for both lignocellulosic materials, being 64 wt% for water-insoluble steam-treated sugarcane bagasse (STB-WI) and 61.5 wt% for water-insoluble steam-treated eucalypt chips (STE-WI), even though different severity factors (log RO) of 3.67 and 3.94 were applied in each case, respectively.

The chemical composition of STB-WI contained 46.50 % glucans and 2.74 % xylans, whereas STE-WI had 56.34 % glucans and only 1.07 % xylans, with acetic acid being undetectable in both substrate acid hydrolysates (Table 1). The ash content of STB-WI was higher than that of sugarcane bagasse and this was probably a result of its abrasiveness when processed at high total solids. STB-WI had a higher acid-insoluble lignin content compared to STE-WI as well as a higher amount of dehydrated pentoses, which were attributed to the presence of arabinoxylans in sugarcane bagasse. Also, the amount of dehydrated pentoses in steam-treated substrates was much lower than that of native materials, with hydroxymethylfurfural becoming the main sugar dehydration by-product. This observation was not only associated to the lower hemicellulose content of steam-treated substrates but also to the higher chemical accessibility of their steam-treated glucans.

Aguiar et al. [28] steam-treated sugarcane bagasse at 210 °C for 4 min for a severity factor (log RO) of 3.84. The chemical composition of the resulting material showed 56.6, 5.3 and 33.0 % of glucans, pentosans and total lignin, respectively. Compared to Table 1, it is clear that the use of higher severity factors led to a more extensive removal of the sugarcane bagasse hemicellulose component. On the other hand, Martin-Sampedro et al. [29] steam-exploded E. globulus chips at various pretreatment severities and produced substrates with relatively high hemicellulose contents. For instance, substrates containing 53.4 % glucan, 12.7 % xylan and 21.9 % lignin were obtained by steam explosion at a log RO of 3.35. Such xylan content is much higher than that of STE-WI in Table 1 and this was an effect of pretreatment at a lower severity factor. However, differences in pretreatment procedure as well as in the chemical composition of both eucalypt species may have been highly influential as well.

Enzymatic hydrolysis

The Fig. 1 shows the logarithmic profile of glucose release that was obtained after 72 h enzymatic hydrolysis of both pretreated materials with 62.5 mg of Cellic CTec3 g−1 TS, which is equivalent to 13.3 FPU g−1 TS. Despite their similar enzymatic hydrolysis profile, conversion of cellulose to soluble sugars was higher for eucalypt compared to bagasse. The final concentrations in glucose equivalents (GlcEq) was 103 g L−1 for STB-WI and 125 g L−1 for STE-WI and these conversion values were approximately 95 % of the available glucans in both cases, with cellobiose being always a minor component of the substrate hydrolysates (less than 1 %).

These hydrolysis procedures were carried out in a Labfors 5HT BioEtOH reactor with a total capacity of 3.2 L using shaft with multiple stirrers to ensure proper mixing of the substrate slurry (Fig. 2).

Ramos et al. [2] produced steam-exploded substrates from sugarcane bagasse at 180 °C for 10 min in the presence of 9.5 mg phosphoric acid g−1 (dry basis). Enzymatic hydrolysis was performed in shake flasks at 20 wt% TS with an EL of 62.5 mg of Cellic CTec2 g−1 cellulose. Despite the use of an exogenous acid catalyst at different pretreatment conditions, 76.8 g L−1 glucose was produced in 72 h of hydrolysis while 103 g L−1 was achieved with STB-WI in this study using the Labfors 5HT BioEtOH bioreactor under otherwise identical reaction conditions. This better hydrolysis performance can be explained by differences in substrate accessibility but also by differences in the hydrolysis procedure, since the later glucose release was obtained under stepwise substrate addition (fed-batch feeding) and a more efficient mechanical agitation.

Martins et al. [30] produced cellulosic ethanol from sugarcane bagasse after pretreatment by alkaline hydrogen peroxide. Enzymatic hydrolysis for 24 h using 15 FPU g−1 (Trichoderma reesei ATCC 26921) plus 25 CBU g−1 (Aspergillus niger) produced 55.2, 69.6 and 78.5 g L−1 glucose at 10, 15 and 20 wt% TS, respectively. In another study, Horn and Eijsink [31] pretreated hardwood poplar by steam explosion at 210 °C for 10 min (log RO of 4.24) and the resulting substrate was hydrolysed for 24 h with 25 FPU g−1 TS of Econase, resulting in 33, 34 and 36 g L−1 glucose at 10, 12.5 and 15 wt% TS, respectively. In this work, STB-WI reached similar values of 75.27 g L−1 glucose after 24 h of hydrolysis while STE-WI resulted in an even better glucose yields of 98.18 g L−1. However, in both cases, hydrolysis was carried out at 20 wt% using only 13.3 FPU g−1 TS of Cellic CTec3.

Fermentation

The fermentation trials were performed with slightly different initial glucose concentrations of 58 and 60 g L−1 for STB-WI and STE-WI, respectively (Fig. 3). At the end of this process, 25.65 g L−1 ethanol and 87.1 % fermentation efficiency were obtained from STB-WI while STE-WI yielded 27.31 g L−1 ethanol for an efficiency of 88.1 %. Glucose consumption was complete after 12 h, suggesting that this process could have been interrupted at this time without any loss in fermentation efficiency. The corresponding ethanol productivities were 1.3 g L−1 h−1 for STB-WI and 1.4 g L−1 h−1 for STE-WI after 24 h of total fermentation time. However, in 12 h of fermentation, these values increased to 2.1 and 2.3 g L−1 h−1, respectively. Martins et al. [30] fermented substrate hydrolysates containing 60 g L−1 glucose using an industrial strain of S. cerevisiae and obtained 1.6 g L−1 h−1 ethanol in 16 h for a fermentation efficiency of 84.5 %. However, this study involved pretreated substrates that were derived from sugarcane bagasse by alkaline hydrogen peroxide pretreatment.

Romaní et al. [32] produced cellulosic ethanol from pretreated substrates that were produced by non-isothermal autohydrolysis of E. globulus chips. In this pretreatment procedure, the reactor vessel was heated up to 210 °C and, when this temperature was reached, the heating system was disabled and the reactor was cooled down to ambient temperature for a total pretreatment time of 50 min. This way, pretreated substrates were produced and whole pretreatment slurries were submitted to SSF for cellulosic ethanol production. After 120 h of SSF at 15.6 wt% TS using 22.5 FPU g−1 of Cellic CTec2, 500 UI g−1 of Cellic HTec2 and 1.8 g L−1 S. cerevisiae PE-2, the resulting ethanol productivity after 72 h was 0.63 g L−1 h−1 for a fermentation efficiency of 94.7 %. Also, when a 24 h pre-hydrolysis step was used prior to simultaneous saccharification and fermentation (pSSF), the corresponding ethanol productivity and fermentation efficiency were lower at 0.55 g L−1 h−1 and 92.1 %, respectively. Since pSSF usually gives better ethanol productivities than SSF [23, 33], this unexpected result was probably due to the presence of inhibitors in the fermentation media. By contrast, Neves et al. [24] used water-washed steam-exploded sugarcane bagasse (195 °C for 7.5 min) for cellulosic ethanol production under both SSF and pSSF configurations and the latter reached the same ethanol concentration in half of the time required by the former, which corresponded to ethanol productivities of 0.39 and 0.63 g L−1 h−1, respectively. However, these results were obtained in the absence of fermentation inhibitors using low enzyme loadings of Cellic CTec2 and the S. cerevisiae strain Thermossac Dry for fermentation. In the SHF configuration used in the present study, the total conversion time for both bagasse and eucalypt substrates was 84 h (72 h for hydrolysis and 12 h for fermentation). Therefore, the corresponding ethanol productivities were much lower at 0.31 and 0.33 g L−1 h−1, respectively. However, these values cannot be compared to those described above because the strategy used for fermentation was completely different.

Comparison between substrates

When the results obtained in this work were projected to 1 t (1000 kg) of processed biomass, it seemed that E. urograndis was the best biomass for cellulosic ethanol production (Table 2). These projections were calculated by considering the recovery yield of water-washed steam-treated fractions (STB-WI and STE-WI), the amount of glucose that was obtained after enzymatic hydrolysis and the corresponding fermentation efficiency for ethanol production. Eucalypt chips presented a slightly lower recovery yield of the STB-WI fraction but its susceptibility to enzymatic hydrolysis was considerably higher, yielding 17 % more glucose than the corresponding STB-WI fraction after 72 h of hydrolysis. On the basis of these, 218.5 L t−1 ethanol were obtained from E. urograndis chips while bagasse reached only 178.0 L t−1 ethanol. These numbers are considerably high if compared to the theoretical amount of ethanol that can be produced from both sugarcane bagasse and eucalypt steam-exploded substrates, whose maximum fermentation efficiency produces 204.4 and 248.0 L t−1 ethanol, respectively. Nevertheless, it is important to mention that 7.1 t of sugarcane are necessary to produce 1 t of dry sugarcane bagasse [5, 6].

According to Ramburan [34], sugarcane reaches harvest maturity after 12 months in equatorial and hot tropical regions. By contrast, the complete eucalypt harvest cycle usually takes seven years [35]. One effective way to achieve a more realistic comparison between these two biomass types is to consider their average annual productivities, which are projected to be around 20.16 t ha−1 year−1 for sugarcane bagasse [5] and 25.92 t ha−1 year−1 for E. urograndis on wet basis [36]. This later average annual productivity, which was calculated using a density of 576 kg m−3, is very similar to the average value reported Dougherty and Wright [37] for Eucalyptus spp.. Hence, eucalypt plantations are able to achieve cellulosic ethanol productivities of 2832.2 L ha−1 year−1 while sugarcane bagasse would produce a 36.6 % lower value of around 1794.5 L ha−1 year−1. However, sugarcane has the advantage of producing ethanol from first generation, which is estimated to be 80 L t−1 in average [38]. Based on the average biomass productivity of 72 t ha−1 year−1 that was obtained in the last Brazilian harvest season [5], this corresponds to 5760.0 L ha−1 year−1 of ethanol on wet basis or a total of 7554.5 L ha−1 year−1 if both first and second generation technologies are added together. Hence, under the conditions used in this study, bagasse glucans showed the potential to boost the ethanol production from sugarcane culms by 31 %, from the 80 L t−1 of first generation to a total production of 105 L t−1, this without considering the yield increments that are expected to arise from the C5 stream as well as from the utilization of other harvest residues for the same purpose, such as sugarcane leaves and tops. These two possibilities also apply to eucalypt wood chips, whose pruning, selective cut and post-harvest residues are estimated to reach 30 t ha−1 year−1 [39], this without including the roots because its collection is both economically and environmentally unfeasible [40].

Gonzalez et al. [41] performed an economic analysis of cellulosic ethanol production from eucalypt biomass and the profitability of the process was most sensitive to the biomass cost, followed by the biomass carbohydrate content and the enzyme cost. Regarding the biomass cost, the Brazilian average market price for industrial eucalypt chips in 2015 was R$ 77.00 t−1, whereas sugarcane bagasse was selling for roughly R$ 150 t−1 [42, 43]. In fact, both prices varied a lot throughout the year but sugarcane bagasse was always more expensive due to its increased demand for bioenergy applications such as cogeneration. Hence, both biomass types showed good potential for cellulosic ethanol production but E. urograndis chips resulted in the highest yields of 218.5 L ethanol t−1, with the added value of being found at a relatively low cost.

Conclusion

Pretreatment of sugarcane bagasse and eucalypt chips by steam explosion resulted in high yields of enzymatic hydrolysis at high total solids and a relatively low enzyme loading. However, the glucose yield was higher for steam-treated eucalypt, giving yields 25 % higher than those of steam-treated bagasse. With regard to fermentation, both hydrolysates were readily fermented in good yields by an industrial yeast strain of S. cerevisiae, achieving productivity values higher than 2 g L−1 h−1 after only 12 h. However, when these results were projected to 1 t of processed biomass, eucalypt chips showed the greatest potential for bioconversion, giving around 40 L of ethanol t−1 more than sugarcane bagasse.

Experimental

Sugarcane bagasse was obtained from the Cane Technology Center (CTC, Piracicaba, SP, Brazil) and industrial chips of E. urograndis were provided by EMBRAPA-Florestas (Colombo, PR, Brazil). The commercial enzyme preparation used for hydrolysis (Cellic® CTec3) was provided by Novozymes Latin America (Araucária, PR, Brazil). The yeast used for fermentation was Thermosacc® Dry, a commercial Saccharomyces cerevisiae preparation produced by Lallemand Specialties Inc. (Milwaukee, WI, EUA).

Chemical analysis of lignocellulosic materials

The materials were subjected to extraction in a Soxhlet apparatus for the determination of their total extractive contents following the NREL/TP-510-42619 method [44]. This way, milled eucalypt chips (40–60 mesh) were extracted with ethanol 95 % while milled bagasse (40–60 mesh) was extracted with water followed by ethanol 95 %. The moisture and ash contents were determined according to the NREL/TP-510-42621 [45] and NREL/TP-510-42622 [46] methods, respectively. The chemical composition of both cellulosic materials was determined according to the NREL/TP-510-42617 [47] and NREL/TP-510-42618 [48] methods, before and after pretreatment, generating the acid insoluble lignin (determined gravimetrically) and the acid soluble lignin (determined by UV spectroscopy), respectively. Carbohydrate composition was determined in the resulting acid hydrolysates by HPLC using a Shimadzu (Kyoto, Japan) HPLC model LC20AD and an Agilent (Santa Clara, CA, EUA) Hi-Plex-H column at 65 °C that was eluted with 5 mmol L−1 H2SO4 at a flow rate of 0.6 mL min−1. Detection was carried out by both refractive index (Shimadzu, model RID10A) and UV spectrophotometry using a photodiode array detector (Shimadzu, model SPD-M10Avp). The quantification was performed by external calibration (0.01–1 g L−1) using a series of standard solutions for each component of interest: cellobiose, glucose, xylose, arabinose, formic acid, acetic acid, furfural and hydroxymethylfurfural, the latter two used for controlling the dehydration of pentoses and hexoses, respectively.

Pretreatment by steam explosion

Pretreatment by steam explosion was carried out in a 10 L stainless steel reactor that was provided with sensors to control reaction parameters such as the pretreatment pressure, temperature and time. The steam explosion experiments were performed under pre-optimized conditions to recover most of the three main biomass components and to increase the susceptibility of the resulting substrate to enzymatic hydrolysis and fermentation. These conditions correspond to autohydrolysis at 195 °C for 7.5 min for sugarcane bagasse [49] and 210 °C for 5 min for eucalypt chips (unpublished data). The severity factor (log RO) of these pretreatment conditions was calculated according to Overend e Chornet [50], where T (°C) is temperature and t (min) is residence time in the reactor (Eq. 1).

After pretreatment, the resulting steam-treated material was immediately filtered through a cheese cloth using a Büchner funnel. The fiber retentate was suspended in water at 5 wt% TS, washed for 1 h at room temperature under mechanical stirring and filtered once again. The resulting steam-treated materials were named water-insoluble steam-treated sugarcane bagasse (STB-WI) and water-insoluble steam-treated eucalypt (STE-WI). Pretreatment mass yields were calculated by difference before and after pretreatment, always in relation to the dry mass of the corresponding materials.

Enzymatic hydrolysis

Enzymatic hydrolyses were carried out in a Labfors 5 BioEtOH reactor (Infors-HT, Bottmingen, Switzerland) using shaft with multiple stirrers during 72 h at 50 °C and 150 rpm. Cellic CTec3 was used at an EL of 62.5 mg g−1 dry substrate in 50 mmol L−1 acetate buffer, pH 5.2. EL was expressed in relation to the wet mass of the enzyme preparation and its total cellulase activity was determined according to Ghose [51]. The reactor was fed with pretreated material by adding 5 wt% TS at every 1.5 h, reaching 20 wt% TS in 4.5 h for a total reaction volume of 2.5 L. Aliquots of 0.5 mL were withdrawn in different times and these were analysed by HPLC as mentioned earlier. The results were expressed in glucose equivalents (GlcEq = glucose + cellobiose × 1.0526) using both glucose and cellobiose solutions as reference standards (0.25 to 5 g L−1). Hydrolysis yields were expressed in relation to the glucan content of the pretreated substrates.

Fermentation

Fermentation was performed in duplicate at 35 °C for 20 h by applying a S. cerevisiae Thermosacc Dry yeast strain to the substrate hydrolysates obtained after enzymatic hydrolysis. The fermentation medium contained 20 mL of hydrolysate, 50 mmol L−1 acetate buffer pH 4.8, 1.0 g L−1 yeast extract, 0.5 g L−1 (NH4)2PO4, 0.025 g L−1 MgSO4·7H2O and 1.0 g L−1 of Thermosacc Dry for a total reaction volume of 100 mL. Aliquots of 0.3 mL were withdrawn in different times and these were analysed by HPLC as mentioned earlier, with glucose and ethanol solutions as reference standards (0.25–5 g L−1). Production of ethanol was expressed in g L−1 while the corresponding ethanol productivity (or the rate of ethanol production) was calculated in g L−1 h−1.

Abbreviations

- EL:

-

enzyme loading

- FPU:

-

filter paper unit

- GlcEq:

-

glucose equivalents (glucose + cellobiose × 1.0526)

- HPLC:

-

high performance liquid chromatography

- log RO :

-

severity factor

- NREL:

-

National Renewable Energy Laboratory

- PDA:

-

photodiode array

- pSSF:

-

pre-hydrolysis followed by simultaneous saccharification and fermentation

- RID:

-

refractive index detector

- SHF:

-

separated hydrolysis and fermentation

- SSF:

-

simultaneous saccharification and fermentation

- STB-WI:

-

water-insoluble, steam-treated sugarcane bagasse

- STE-WI:

-

water-insoluble, steam-treated eucalypt

- TS:

-

total solids

References

Gupta A, Verma JP (2015) Sustainable bio-ethanol production from agro-residues: a review. Renew Sust Energ Rev 41:550–567

Ramos LP, Silva L, Ballem AC, Pitarelo AP, Chiarello LM, Silveira MHL (2015) Enzymatic hydrolysis of steam-exploded sugarcane bagasse using high total solids and low enzyme loadings. Bioresour Technol 175:195–202

Yang B, Wyman CE (2008) Pretreatment: the key to unlocking low-cost cellulosic ethanol. Biofuels Bioprod Biorefin 2:26–40

Mohanram S, Amat D, Choudhary J, Arora A, Nain L (2013) Novel perspectives for evolving enzyme cocktails for lignocellulose hydrolysis in biorefineries. Sustain Chem Process 1:15

Carvalho DM, Sevastyanova O, Penna LS, Silva BP, Lindström ME, Colodette JL (2015) Assessment of chemical transformations in eucalyptus, sugarcane bagasse and straw during hydrothermal, dilute acid, and alkaline pretreatments. Ind Crops Prod 73:118–126

Oliveira IS, Chandel AK, Silva MB, Silva SS (2013) Environmental assessment of residues generated after consecutive acid-base pretreatment of sugarcane bagasse by advanced oxidative process. Sustain Chem Process 1:20

Lima MA, Lavorente GB, Silva HKP, Bragatto J, Rezende CA, Bernardinelli OD et al (2013) Effects of pretreatment on morphology, chemical composition and enzymatic digestibility of eucalyptus bark: a potentially valuable source of fermentable sugars for biofuel production—part 1. Biotechnol Biofuels 6:75

Barbosa LCA, Maltha CRA, Cruz MP (2005) Composição química de extrativos lipofílicos e polares de madeira de Eucalyptus grandis. Ciência Engenharia 15(2):13–20

Kullan ARK, van Dyk MM, Jones N, Kanzler A, Bayley A, Myburg AA (2012) High-density genetic linkage maps with over 2400 sequence-anchored DArT markers for genetic dissection in an F2 pseudo-backcross of Eucalyptus grandis × E. urophylla. Tree Genet Genomes 8:163–175

Stanturf JA, Vance ED, Fox TR, Kirst M (2013) Eucalyptus beyond its native range: environmental issues in exotic bioenergy plantations. Int J For Res. doi:10.1155/2013/463030

Bozell JJ, Petersen GR (2010) Technology development for the production of biobased products from biorefinery carbohydrates—the US Department of Energy’s “Top 10” revisited. Green Chem 12:539–554

Clark JH, Luque R, Matharu AS (2012) Green chemistry, biofuels, and biorefinery. Annu Rev Chem Biomol Eng 3:183–207

Maity SK (2015) Opportunities, recent trends and challenges of integrated biorefinery: part I. Renew Sust Energ Rev 43:1427–1445

Carrasco C, Baudel HM, Sendelius J, Modig T, Roslander C, Galbe M et al (2010) SO2-catalyzed steam pretreatment and fermentation of enzymatically hydrolyzed sugarcane bagasse. Enzyme Microb Technol 46(2):64–73

Ramos LP (2003) The chemistry involved in the pretreatment of lignocellulosic materials. Quím Nova 26(6):863–871

Rocha GJM, Gonçalves AR, Oliveira BR, Olivares EG, Rossel CEV (2012) Steam explosion pretreatment reproduction and alkaline delignification reactions performed on a pilot scale with sugarcane bagasse for bioethanol production. Ind Crops Prod 35(1):274–279

Pitarelo AP, Silva TA, Peralta-Zamora PG, Ramos LP (2012) Efeito do teor de umidade sobre o pré-tratamento a vapor e a hidrólise enzimática do bagaço de cana-de-açúcar. Quím Nova 35(8):1502–1509

Schütt F, Westereng B, Horn SJ, Puls J, Saake B (2012) Steam refining as an alternative to steam explosion. Bioresour Technol 111:476–481

Wingren A, Galbe M, Zacchi G (2003) Techno-economic evaluation of producing ethanol from softwood: comparison of SSF and SHF and identification of bottlenecks. Biotechnol Progress 19(4):1109–1117

Modenbach AA, Nokes SE (2013) Enzymatic hydrolysis of biomass at high-solids loadings–a review. Biomass Bioenergy 56:526–544

Roche CM, Dibble CJ, Knutsen JS, Stickel JJ, Liberatore MW (2009) Particle concentration and yield stress of biomass slurries during enzymatic hydrolysis at high-solids loadings. Biotechnol Bioeng 104(2):290–300

Yang J, Zhang X, Yong Q, Yu S (2011) Three-stage enzymatic hydrolysis of steam-exploded corn stover at high substrate concentration. Bioresour Technol 102(7):4905–4908

Hoyer K, Galbe M, Zacchi G (2013) Influence of fiber degradation and concentration of fermentable sugars on simultaneous saccharification and fermentation of high-solids spruce slurry to ethanol. Biotechnol Biofuels 6:145

Neves PV, Pitarelo AP, Ramos LP (2016) Production of cellulosic ethanol from sugarcane bagasse by steam explosion: effect of extractives content, acid catalysis and different fermentation technologies. Bioresour Technol 208:184–194

Szczerbowski D, Pitarelo AP (2014) Zandoná Filho A, Ramos LP. Sugarcane biomass for biorefineries: comparative composition of carbohydrate and non-carbohydrate components of bagasse and straw. Carbohydr Polym 114:95–101

Pinto PC, Evtuguin DV (2005) Pascoal Neto C. Structure of hardwood glucuronoxylans: modifications and impact on pulp retention during wood kraft pulping. Carbohydr Polym 60(4):489–497

Schuchardt U, Ribeiro ML, Gonçalves AR (2001) A indústria petroquímica no próximo século: como substituir o petróleo como matéria-prima? Quim Nova 24(2):247–251

Aguiar RS, Silveira MHL, Pitarelo AP, Corazza ML, Ramos LP (2013) Kinetics of enzyme-catalyzed hydrolysis of steam-exploded sugarcane bagasse. Bioresour Technol 147:416–423

Martin-Sampedro R, Revilla E, Villar JC (2014) Enhancement of enzymatic saccharification of Eucalyptus globulus: steam explosion versus steam treatment. Bioresour Technol 167:186–191

Martins LHS, Rabelo SS, Costa AC (2015) Effects of the pretreatment method on high solids enzymatic hydrolysis and ethanol fermentation of the cellulosic fraction of sugarcane bagasse. Bioresour Technol 191:312–321

Horn SJ, Eijsink VG (2010) Enzymatic hydrolysis of steam-exploded hardwood using short processing times. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 74(6):1157–1163

Romaní A, Ruiz HA, Pereira FB, Teixeira JA, Domingues L (2014) Integrated approach for effective bioethanol production using whole slurry from autohydrolyzed Eucalyptus globulus wood at high-solid loadings. Fuel 135:482–491

Liu ZH, Qin L, Zhu JQ, Li BZ, Yuan YJ (2014) Simultaneous saccharification and fermentation of steam-exploded corn stover at high glucan loading and high temperature. Biotechnol Biofuels 7:167

Ramburan S (2015) Interactions affecting the optimal harvest age of sugarcane in rainfed regions of South Africa. Field Crops Res 183:276–281

Almeida AC, Soares JV (2003) Comparação entre uso de água em plantações de Eucalyptus grandis e Floresta Ombrófila densa (Mata Atlântica) na costa leste do Brasil. Revista Árvore 27(2):159–170

Comércio Ambiental (2014) http://www.comercioambiental.com.br/mudas/eucalipto/. Accessed 19 Feb 2016

Dougherty D, Wright J (2012) Silviculture and economic evaluation of eucalypt plantations in the southern US. Bioresources 7(2):1994–2001

Leal MRLV, Nogueira LAH (2014) The sustainability of sugarcane ethanol: the impacts of the production model. Chem Eng Trans 37:835–840

Wrobel-Tobiszewska A, Boersma M, Sargison J, Adams P, Jarick S (2015) An economic analysis of biochar production using residues from Eucalypt plantations. Biomass Bioenergy 81:177–182

Wu J, Liu Z, Huang G, Chen D, Zhang W, Shao Y et al (2015) Response of soil respiration and ecosystem carbon budget to vegetation removal in Eucalyptus plantations with contrasting ages. Sci Rep 4:6262. doi:10.1038/srep06262

Gonzalez R, Treasure T, Phillips R, Jameel H, Saloni D, Abt R et al (2011) Converting Eucalyptus biomass into ethanol: financial and sensitivity analysis in a co-current dilute acid process. Part II. Biomass Bioenergy 35(2):767–772

Cana Online (2015) http://www.canaonline.com.br/conteudo/comercio-de-bagaco-de-cana-virou-bom-negocio-para-as-usinas.html#.VsNt8rQrKt9. Accessed 16 Feb 2016

Secretaria de Estado da Agricultura e do Abastecimento do Estado do Paraná (2015) http://www.agricultura.pr.gov.br/arquivos/File/deral/florestais/Flor2015abr.xls. Accessed 21 Feb 2016

Sluiter A, Ruiz R, Scarlata C, Sluiter J, Templeton D (2008a) Determination of extractives in biomass. Laboratory analytical procedure: Technical Report: NREL/TP-510-42619 National Renewable Energy Laboratory, Golden, Colorado, USA

Sluiter A, Hames B, Hyman D, Payne C, Ruiz R, Scarlata C, et al (2008b) Determination of total solids in biomass and total dissolved solids in liquid process samples. Laboratory analytical procedure: Technical Report: NREL/TP-510-42621 National Renewable Energy Laboratory, Golden, Colorado, USA

Sluiter A, Hames B, Ruiz R, Scarlata C, Sluiter J, Templeton D (2008c) Determination of ash in biomass. Laboratory Analytical Procedure: Technical Report NREL/TP-510-42622. National Renewable Energy Laboratory, Golden, Colorado, USA

Hyman D, Sluiter A, Crocker D, Johnson D, Sluiter J, Black S, et al (2008) Determination of Acid soluble lignin concentration curve by UV-Vis Spectroscopy. Laboratory analytical procedure: Technical Report: NREL/TP-510-42617 National Renewable Energy Laboratory, Golden, Colorado, USA

Sluiter A, Hames B, Ruiz R, Scarlata C, Sluiter J, Templeton D, et al (2012) Determination of structural carbohydrates and lignin in biomass. Laboratory analytical procedure: Technical Report NREL/TP-510-42618. National Renewable Energy Laboratory, Golden, Colorado, USA

Pitarelo AP, Fonseca SF, Chiarello LM, Gírio FM, Ramos LP (2016) Ethanol production from sugarcane bagasse using phosphoric acid-catalyzed steam explosion. J Braz Chem Soc. doi:10.5935/0103-5053.20160075

Overend RP, Chornet E (1987) Fractionation of lignocellulosics by steam-aqueous pretreatments. Phil Trans R Soc A 321(1561):523–536

Ghose TK (1987) Measurement of cellulase activities. Pure Appl Chem 59:257–268

Authors’ contributions

LMC, PVN and CEAR carried out the experimental work, helped designing the study and were always involved in all discussions and data interpretation. LPR coordinated the overall study and analysis of results. All authors suggested modifications to the draft. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by Grants 551404/2010-8 and 311554/2011-3 from CNPq (Brazil). Also, LMC and PVN are grateful to CAPES (Brazil) for providing scholarships to carry this study as well to Novozymes Latin America and Lallemand for providing the enzyme and the yeast strain for hydrolysis and fermentation, respectively.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ information

LPR is Full Professor in Analytical Organic Chemistry at the Federal University of Paraná (UFPR—Curitiba, PR, Brazil). He graduated in Chemistry (1982) at the Catholic University of Paraná in 1982, obtained his Master’s in Biochemistry from UFPR in 1988 and his Ph.D. in Applied Biology from the University of Ottawa in 1992. His research activities involve wood and carbohydrate chemistry, second and third generation biofuels, biomass fractionation using advanced pretreatment technologies, heterogeneous catalysis and several other topics within the main concept of sustainable biorefineries. Currently, he is one of the Associate Editors of the ACS journal Energy and Fuels (since 2012), participates in the Editorial Advisory Board of the Bioethanol Journal (edited by De Gruyter) and BioResources (Raleigh, USA) and has acted as ad-hoc consultant for several companies, leading international science journals and both national and international funding agencies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Chiarello, L.M., Ramos, C.E.A., Neves, P.V. et al. Production of cellulosic ethanol from steam-exploded Eucalyptus urograndis and sugarcane bagasse at high total solids and low enzyme loadings. Sustain Chem Process 4, 15 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40508-016-0059-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40508-016-0059-4