Abstract

The consequences of COVID-19 on the economy and agriculture have raised many concerns about global food security, especially in Middle Eastern countries, where unsustainable farming practices are widespread. Regarding the unprecedented crisis of the COVID-19 pandemic and the importance of early implementation of prevention programs, it is essential to understand better its potential impacts on various food security dimensions and indicators in these countries. In this scoping review, research databases were searched using a search strategy and keywords developed in collaboration with librarians. The review includes community trials and observational studies in all population groups. Two researchers separately conducted the literature search, study selection, and data extraction. A narrative synthesis was implemented to summarize the findings. The impacts of COVID-19 on three of four dimensions of food security through the food and nutrition system were identified: availability, accessibility, and stability. Disruption of financial exchanges, transportation, and closing of stores led to reduced production, processing, and distribution sub-systems. Rising unemployment, quitting some quarantined jobs, increasing medical healthcare costs, and increasing food basket prices in the consumption sub-system lead to lower access to required energy and nutrients, especially in the lower-income groups. Increased micronutrient deficiency and decreased immunity levels, increased overweight, obesity and non-communicable diseases would also occur. The current review results predict the effect of COVID-19 on food security, especially in vulnerable populations, and develop effective interventions. This review provides information for policymakers to better understand the factors influencing the implementation of these interventions and inform decision-making to improve food security.

PROSPERO identifier: CRD42020185843.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic is a public health emergency affecting the food and nutrition security of millions of people throughout the world. COVID-19 impacts the four dimensions of food and nutrition security: availability, accessibility, consumption, and stability through the food and nutrition systems [1]. Disruptions in all stages of food and nutrition sub-systems (producer, consumer, nutrition) including production, processing, distribution, acquisition, preparation, consumption, digestion, transport, metabolism, and health [2] have been reported [3, 4].

The recent document analysis by B´en´eet al. in low and middle-income countries found that the dimension of food security that had the greatest impact was access, with compelling evidence that both financial and physical access to food was impaired. In contrast, there is no clear evidence that food availability is affected. Overall, the data suggest that food systems have withstood and adapted to the pandemic disruption. However, this flexibility came at a cost, and most system actors had to deal with severe disruptions in their activities. The effects of the pandemic on the utilization dimension (food safety and quality) are unclear due to limited information [5].

It seems that differences in the impact of the pandemic on countries' food security are based on the development and stability of their food systems. For example, COVID-19 created an expected “income shock” to increase the prevalence of food-insecure Canadian households. Despite some demand and supply chain disruptions, a broad and rapid appreciation of food prices was not observed. These conditions show the ability of the Canadian food system to ensure food supply in the short term. To ensure food availability in the long run, experts recommend prioritizing easy cash movements, international exchange, and sustainable transportation [6]. In the USA, preliminary results of the impact of COVID-19 showed approximately one-third increase in household food insecurity. Food insecurity, access issues, and utilizing coping methods were all more common among those who had lost their jobs. There were also significant potential effects on individual health, such as mental health, malnutrition, and future healthcare expenses [7].

There is a particular concern for the Western Cape in Africa regarding the short- and long-term shortage of food supply in domestic markets, fertilizers and plant protection products, and food insecurity in vulnerable communities. Monitoring food access in rural areas, and incredibly remote areas, controlling inflation in food prices, direct and indirect assistance to the most vulnerable households can be helpful in the short term. Over the long term, the expansion in the production of organic fertilizer on the farm regulates domestic food production chains and coordinates industries, importers/suppliers for the basic goods can improve food security in African households. Despite potentially adverse outcomes of the COVID-19 pandemic, it has highlighted the importance of sustainable food production for long-term country sustainability [8, 9].

The economic effects of COVID-19 were also disproportionately observed in developing countries[10]. When the COVID-19 epidemic was in its early stages in Iraq, food availability remained consistent due to stable international food trade flows and good local production. Basic food prices did not change significantly; however, vegetables particularly tomato—prices fluctuated wildly. The rising number of (COVID-19) cases in Iraq, combined with movement restrictions imposed to contain the virus, had a cascading effect on livelihoods, particularly for casual laborers and low-income workers, putting small and medium-sized businesses, including those operating in the food and agriculture sector. Importing from various sources, investing in a food security early warning system, and promoting social protection policies may help Iraq's food and agriculture sector be more resilient to present and future shocks [11]. These conditions can also be an opportunity to introduce digital innovation to increase food security [12]. In Indonesian urban areas, the poverty rate increased from 9.4% in 2019 to 9.8% in 2020 after the COVID-19 outbreak, primarily. Household consumption expenditure decreased by 5.5%, mainly due to the implementation of large-scale social distancing policies in various regions, business closures, lockdowns, and movement restrictions. The government of Indonesia continued supporting the most vulnerable groups through social protection programs. The Ministry of Agriculture has implemented its subsidized credit scheme program (KUR) to support the agricultural sector [13].

Studies indicated that during the early stages of COVID-19, Iranian households decreased their consumption of several food groups, particularly meat [14, 15]. Personal savings, occupation status, household income, and nutrition knowledge of household heads were the main socio-economic determinants of household food insecurity during COVID-19. Strategies to improve food security during a pandemic include e-commerce, free food baskets for poor households, nutrition education through media, and support for affected people [16]. Figure 1 shows an overview of COVID-19 food security pathways and interactions [17] based on the evidence from reviews [18].

COVID-19 food security pathways and interactions [17]. FDI = Foreign direct investment; NSAG, Non-state armed group; ODA, Official development assistance

While there are some studies on the worrying impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on household incomes/purchasing power, food supply chains, food safety, agricultural livelihoods and food availability, diet quality, and nutrition status [19,20,21,22,23], little is known about food security in the Middle East countries [24], where unsustainable farming practices are widespread [25]. Due to political turmoil, social upheaval, unprecedented mass immigration, and water scarcity, Middle Eastern countries such as Afghanistan, Bahrain, Djibouti, Egypt, Iran (the Islamic Republic of), Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Oman, Pakistan, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sudan, Syrian Arab Republic, Tunisia, United Arab Emirates, and Yemen are facing unprecedented challenges to their food security [26, 27], and the COVID-19 crisis can exacerbate these challenges. Regarding the unprecedented crisis of the COVID-19 pandemic and the importance of early implementation of prevention programs, it is essential to understand better its potential impacts on various dimensions and indicators of food security in these regions.

The most basic step in making a final judgment about the possible effects of the current crisis on the population’s food security is to refer to the evidence and review-related studies [28]. Scattered studies have been conducted in the Middle East and other parts of the world, but the common effects of COVID-19 on food security, the similarities and differences of each region, and the localized approach for each region, besides the general strategies to deal with these effects, are not known. Therefore, in this study, the critical food security indicators affected by this crisis were identified in at-risk populations to design effective interventions for maintaining and improving the food security status of all people under these conditions. The results can provide the information needed to design food and nutrition security programs in pandemics according to the conditions of each country and the factors influencing the successful implementation of these programs, especially in vulnerable groups.

Research questions

-

a)

What dimensions of food security have been affected by the COVID-19 outbreak?

We aimed to answer this question through a scoping review of related studies to summarize the impact of COVID-19 on food security and identify the more affected dimensions, including availability, access, utilization, and stability during the COVID-19 outbreak in the Middle East countries.

-

b)

What are the principal policies and coping strategies of interventions?

We aimed to identify the main policies and strategies to cope with the food insecurity crisis during the COVID-19 outbreak in this region.

Sub-objectives, such as assessing obesity and mental health problems related to COVID-19 were also considered.

Methods

Study registration

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) Checklist [29] was used to guide the study design. This review was registered in the Prospective International Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) as the overall project entitled “The relationship between COVID-19 pandemic and food security at individual and household level: a systematic review” (NO. CRD42020185843).

Study selection criteria

Type of studies

A sensitive search strategy developed by a grouping of terms, phrases, and keywords associated with potential outcome measurements [e.g., (safety OR secur* OR insecur* OR povert* OR sufficen* OR insuffic* OR risk* OR uncertain* OR hygien* OR affluen* OR suppl* OR reserve* OR avail* OR access* OR stabil* OR utilize*) AND (covid* OR coronavir* OR sars)] was used. We worked closely with an experienced librarian to advice on and implement the search strategy (see Additional file 1).

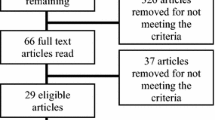

The electronic databases, including PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science were searched from December 2019 onwards for relevant studies. The authors reviewed 1777 studies (PubMed = 557, Scopus = 375, Web of Science = 845) related to the change in food security status and/or its indicators due to the COVID-19 pandemic and related interventions. Therefore, various community trials and observational studies, including cross-sectional, case–control, and longitudinal studies, were reviewed. Google Scholar was also searched to identify gray literature.

Type of populations

Various population groups, such as children and adults, as well as disadvantaged groups, were included.

Types of interventions

In the current study, COVID-19 is considered an intervention factor. Food security and/or its indicators at the individual, household, or country level were evaluated as factors influenced by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Types of outcomes of interests

Due to the complexity of food security, we assessed outcomes at different levels, including national, household, and individual. The results of our preliminary search revealed considerable various outcomes across food security and COVID-19. As a result, we included a structured approach to the outcomes according to the framework of food security definition [30,31,32]. Based on the available evidence [5, 31] and the approval of the research team [33], indicators of food security dimensions are presented as primary outcome measures in Table 1.

Our search yielded studies that assessed the relationship between the COVID-19 pandemic and the food security of individuals, households, and countries in different groups. To organize the recovered documents and eliminate duplicates, we used EndNote software. The Systematic Review-Assistant Deduplication Module (SRA-DM)was used to validate the de-duplication process [34].

Two people independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of articles using the inclusion criteria checklist. In case of disagreement, the inclusion decision of the article was finalized through discussion and exchange of views between the research team. At this screening stage, irrelevant items were removed according to the title and abstract. Then, two researchers reread the full text of the articles separately and included them based on the checklist of inclusion criteria.

Data extraction

Data were extracted separately by two authors (AD and FMN) on a standardized data extraction form. Extracted data included study characteristics (author (s), publication year, study design, setting, and time frame), population characteristics (sample size, age, and sex of subjects), and food insecurity outcomes (change in availability, access, utilization, and stability indicators, due to the COVID-19 pandemic).

Assessment of risk of bias

To assess the quality of the included studies, we used The Newcastle–Ottawa quality assessment scale (NOS) [35]. The total score of this scale is nine stars, and > 7 stars are considered high quality. One reviewer assessed the data quality, and a second reviewer checked it. Any disagreements were settled by discussion among the reviewers, and if required, a third reviewer was consulted.

Data analysis

For continuous outcomes with baseline data, we reported the mean difference (MD) between the change in food security and/or its indicators before and after the COVID-19 pandemic if all studies have used the same measures for the outcomes. Differences in partial frequencies were presented for qualitative variables, too. A narrative summary of the findings was done by grouping the results based on the region and outcome measurement.

Results

Study characteristics

Characteristics of 20 studies included in the review conducted in the Middle Eastern countries on the food insecurity domains during the COVID-19 pandemic are summarized in Table 2.

A large number of the studies were done with the help of international organizations, including FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization) [36,37,38,39], IFPRI (International Food Policy Research Institute) [40,41,42,43], WFP (World Food Programme) [12, 44], World Bank [12], IFAD (The International Fund for Agricultural Development) [12], IOM (International Organization for Migration) [44], and CARE[45]. Some of them were cross-sectional online surveys that used questionnaires designed on different virtual platforms, and others analyzed the existing data and predicted the trends in food security.

Effects of COVID-19 on food availability, access, and stability are found; however, indicators of utilization were not reported in any of the studies reviewed. The dimensions of food stability and access have been more impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic in the region, and more people reported experiencing more severe degrees of food insecurity mainly because of a significant rise in all food prices, while the income was reduced due to quarantine or job loss.

Strategies to counteract food insecurity

Using different strategies to counteract the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the dimensions of food security has been reported in the countries of the region: gradually opening the economy again was critical for avoiding permanent job losses and increases in poverty and providing opportunities for fostering more private sectors [40, 46], distributing free food baskets for poor households [16, 47], extending e-marketing [12], providing nutrition consultative, encouraging donors to support families [48], economic diversification, greater resilience to withstand economic shocks [43], investing in a food security early warning system and restructuring social protection policy [12].

Quality of the studies

More than half of the studies have high quality, because they meet all criteria, especially in measuring food insecurity transparently. Failure to identify confounding factors and use strategies to deal with them was the main reason for the medium quality of the reviewed studies.

Food insecurity in Middle Eastern countries during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Table 3 categorizes the food insecurity studies conducted in the Middle Eastern countries based on the World Bank classification of their national income [56] during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, there are some exceptions; Lebanon and Iran, as two upper-middle-income countries for many years, now move to the lower-middle-income group, and in contrast, Iraq is an upper-middle-income one. International organizations conducted most of the studies in the low/lower-middle-income countries using primary and secondary data from qualitative and quantitative methods, whereas researchers from the high/upper-middle countries conducted the studies during the COVID-19 pandemic mostly via an online survey using FI-measuring questionnaires. In the first group of countries, severe disruption of food sub-systems occurred, food prices rose, and many poor people also suffered as their employment due to the breakdown of supply chains-transporting, marketing, and selling food, increasing food insecurity, energy, and nutrient deficiency for both urban and rural poor. In high/upper middle-income countries, unaffected food supply led to a rush toward supermarkets and stocking, less food price increase occurred (with some exceptions, e.g., Iran due to the special conditions of sanction), and income loss mostly affected vulnerable people, e.g., refugees.

Discussion

The review of the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on food security shows that some governments have often succeeded in providing enough food supply (availability), but they acted differently in terms of population accessibility to food and its price stability. An increase in food prices in most countries yielded in stocking and decreased the purchasing power of the community. No effect on the utilization dimension was found; only in a National Food and Nutrition Surveillance of Iran protocol by Resekhi et al. [11] assessing the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on anthropometric indices of under 5-year-old children was proposed. It seems that differences in the impact of the pandemic on countries' food security are based on the development and stability of their food systems; however, this interpretation of data needs to be studied and examined more closely in different countries with different degrees of development and speeding of the disease.

Based on the reports of FAO and the World Bank, the prevalence of undernourishment (percentage of the population with insufficient energy intake) and food insecurity increased slightly in the COVID-19 pandemic-affected MENA countries; however, the most increases were found in conflict-affected countries (availability domain). The rate of price increases over this period has been moderate, and it seems that the expected decline in incomes of the different social groups, especially the informal sector and vulnerable poor segments of society, represents a major risk on the demand side (access and stability domains). The prevalence of underweight, wasting, and stunting in children under 5 years of age has declined steadily since 2000 (utilization domain) [57, 58]. A study in Sub-Saharan Africa found that COVID-19 negatively affects all four indicators of food security without exception [59].

The findings of the current study confirm that the final outcomes of COVID-19 will most certainly vary from country to country, depending not only on the epidemiological scenario but also on the pre-COVID socioeconomic development level, baseline situation, and shock resilience [52, 54]. Conflict, siege, and locust invasion further undermine food security in Middle Eastern and East African nations, such as Yemen and Somalia. Due to record low oil prices, countries that rely on oil for the majority of their export revenues may face challenges. Algeria and Iran, both of which have low hard currency reserves, will be affected. The COVID-19 threat is exacerbated in areas of conflict and crisis, such as the Middle East and East Africa, by sieges, embargos, and other barriers to food access imposed by political and military forces. Millions of Syrian refugees now reside in camps in Turkey, Lebanon, Syria, and Jordan, relying on food aid and cannot practice social distancing [60]. They are more vulnerable than the citizens of the country, and policies should be adopted to protect their food security separately.

Based on IFPRI reports, in the Middle East and North Africa region, the pandemic led to falling remittances and incomes, especially in the service and industry sectors. Food services and tourism-related businesses suffered the most severe disruptions, proportionately harming urban dwellers employed in those sectors, while other parts of the agrifood system have proved more resilient. In particular, the pandemic continues to test the functioning of national food systems and expose the vulnerabilities that come with the heavy dependency of most MENA countries on food imports. All national economies in the region have experienced severe disruptions. The impacts vary across countries and sectors, reflecting differences in both the spread of the pandemic and government responses. The pandemic has caused GDP losses ranging from 1.1% expected in Egypt to 23.0% in Jordan during 2020 [61].In a systematic review of the first-year experience of COVID-19 on food security, disruptions in food production (availability) were reported due to persistently low household incomes and insufficient savings [17].

Along with several advanced technologies and adaptations for population screening and early disease diagnosis [62, 63], general strategies like supporting vulnerable groups through social protection programs are suggested and used in various countries to prevent increasing food insecurity in the COVID-19 epidemic, while different countries, depending on their circumstances, may need localized and specific solutions. Strengthening sustainable agriculture, resilience, and social protection systems are recommended to promote food security in future pandemics [64, 65]. Some unexpected findings from countries [16] can be attributed to the limitations of the studies, especially the generalizability of the sample to the study population, which should be improved in future studies.

In the present conditions, international organizations and developed countries should help low- and middle-income countries to provide the capacity to expand health and social support programs, strengthen food supply chains, and ensure adequate and affordable food sources with the necessary fiscal space and import [66]. While some economic strategies, such as social assistance, can help individuals manage food insecurity during COVID-19, international sanctions can make implementing these solutions extremely difficult, if not impossible [47]. The pandemic is also a strong reminder for countries to rethink their agricultural investment priorities to include (climate), nutrition, and the environment, diversifying food imports and exports, local/traditional foods, and improving the business environment to allow farmers, food producers, and traders to thrive and grow[61, 66,67,68].

The limitation of this systematic review was the limited number of included studies (n = 23), which may reduce the chances of a better interpretation of the results. In addition, although we had planned the systematic review and registered it in PROSPERO under the following title, “The relationship between COVID-19 pandemic and food security at individual and household level: a systematic review”, due to the multi-sectoral impacts of COVID-19 on food security, the lack of access to full-text articles as well as the exclusion of published articles in a language other than English, the research team conducted the study as a scoping review in the Middle East countries. Future systematic reviews in different parts of the world, especially on the main individual, regional, and governmental policies and strategies to cope with the impacts of pandemics on food insecurity and their cost-effectiveness evaluation, can be very helpful.

Conclusion

An increase in food prices in most countries yielded in stocking and decreased the purchasing power of the community. Despite providing enough food supply (availability) in most countries of the region, they acted differently in terms of population accessibility to food and its price stability. The high/upper middle-income countries of the region had little problem in providing food despite their dependence on food imports and their focus was more on price stabilization and access to vulnerable groups. While in low/lower-income countries, almost all parts of the food and nutrition system were disturbed.

The current review results can predict the effect of COVID-19 on the food security of individuals and households, especially in vulnerable groups, and develop effective interventions. In addition, this review can provide policymakers with the information to better understand the factors influencing the implementation of interventions toward mitigating the effects of the pandemic on food security and evidence-informed policy-making to improve food security.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease 2019

- SRA-DM:

-

Systematic review-assistant deduplication module

- NOS:

-

Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale

References

UN: Policy brief: the impact of COVID-19 on food security and nutrition. In.: United Nations; 2020.

Sobal J, Kettel Khan L, Bisogni C. A conceptual model of the food and nutrition system. Soc Sci Med. 1998;47(7):853–63.

FAO. COVID-19 and its impact on food security in the Near East and North Africa: how to respond? Cairo: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; 2020.

FAO, CELAC. Food security under the COVID-19 Pandemic. Rome: FAO at the request of the National Coordination of the Presidency Pro Tempore of Mexico before CELAC; 2020.

Béné C, Bakker D, Chavarro MJ, Even B, Melo J, Sonneveld A. Global assessment of the impacts of COVID-19 on food security. Glob Food Secur. 2021;31:100575.

Deaton BJ, Deaton BJ. Food security and Canada’s agricultural system challenged by COVID-19. Can J Agr Econ. 2020;68:143–9.

Niles MT, Bertmann F, Belarmino EH, Wentworth T, Biehl E, Neff R. The early food insecurity impacts of COVID-19. Nutrients. 2020;12:2096.

Partridge A. The implications of COVID-19 for the supply of key inputs to the Western Cape Agricultural Sector. In: WCDoA COVID-19 Economic Brief #01. Western Cape: Western Cape Government; 2020.

Troskie D. Impact of COVID-19 on agriculture and food in the Western Cape. In: WORKING DOCUMENT (Version 2). Western Cape: Western Cape Department of Agriculture, Western Cape Government; 2020.

Erokhin V, Gao T. Impacts of COVID-19 on trade and economic aspects of food security: evidence from 45 developing countries. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(16):5775.

Rasekhi H, Rabiei S, Amini M, Ghodsi D, Doustmohammadian A, Nikooyeh B, Abdollahi Z, Minaie M, Sadeghi F, Neyestani TR. COVID-19 epidemic-induced changes of dietary intake of Iran population during lockdown period: the study protocol-national food and nutrition surveillance. Nutr Food Sci Res. 2021;8(2):1–4.

ElHajjhassan S, Ahmed T, Meygag A, Robertson TD. Food security in Iraq impact of COVID-19 (with a special feature on digital innovation). In. Iraq: FAO, IFAD, WFP, World Bank Agriculture and Food Global Practice 2020.

Bodamaev S, Tuwo AD, Tandipanga KF, Fauziah RA. INDONESIA COVID-19: Economic and Food Security Implications. In. Edited by Edition d. Indonesia: WFP; 2020.

Nikooyeh B, Rabiei S, Amini M, Ghodsi D, Rasekhi H, Doustmohammadian A, et al. COVID-19 epidemic lockdown-induced changes of cereals and animal protein foods consumption of Iran population: the first nationwide survey. J Health Popul Nutr. 2022;41(1):1–9.

Rabiei S, Ghodsi D, Amini M, Nikooyeh B, Rasekhi H, Doustmohammadian A, et al. Changes in fast food intake in Iranian households during the lockdown period caused by COVID-19 virus emergency, National Food and Nutrition Surveillance. Food Sci Nutr. 2022;10(1):39–48.

Pakravan-Charvadeh MR, Mohammadi-Nasrabadi F, Gholamrezai S, Vatanparast H, Flora C, Nabavi-Pelesaraeie A. The short-term effects of COVID-19 outbreak on dietary diversity and food security status of Iranian households (a case study in Tehran province). J Clean Prod. 2020;281:124537.

Feyertag J, Munden L, Calow R, Gelb S, McCord A, Mason AN. Covid-19 and food security: novel pathways and data gaps to improve research and monitoring efforts. In: London, UK: ODI policy brief; 2021.

Béné C, Bakker D, Chavarro MJ, Even B, Jenny M, Sonneveld A. Impacts of COVID-19 on people’s food security: foundations for a more resilient food system. Washington, DC, USA: International Food Policy Research Institute; 2021.

Éliás B, Jámbor A. Food security and COVID-19: a systematic review of the first-year experience. Sustainability. 2021;13(9):5294.

Kaviani-Rad A, Shamshiri RR, Azarm H, Balasundram SK, Sultan M. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on food security and agriculture in Iran: a survey. Sustainability. 2021;13(18):10103.

Louie S, Shi Y, Allman-Farinelli M. The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on food security in Australia: a scoping review. Nutr Diet. 2022;79(1):28–47.

Mardones F, Rich K, Boden L, Moreno-Switt A, Caipo M, Zimin-Veselkoff N, Alateeqi A, Baltenweck I. The COVID-19 pandemic and global food security. Front Vet Sci. 2020;7:578508.

Sereenonchai S, Arunrat N. Understanding food security behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic in Thailand: a review. Agronomy. 2021;11(3):497.

Abu Hatab A, Krautscheid L, Boqvist S. COVID-19, livestock systems and food security in developing countries: a systematic review of an emerging literature. Pathogens. 2021;10(5):586.

OECD, Food Nations AOotU: OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2018–2027; 2018.

Amery HA. Food security in the middle east. In: Jägerskog A, Schulz M, Swain A, editors. Routledge handbook on middle east security. London: Routledge; 2019. p. 182–98.

Hameed M, Ahmadalipour A, Moradkhani H. Drought and food security in the middle east: an analytical framework. Agric For Meteorol. 2020;281:107816.

Khan K, Kunz R, Kleijnen J, Antes G. Systematic reviews to support evidence-based medicine. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2011.

Tricco A, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien K, Colquhoun H, Levac D, Moher D, Peters M, Horsley T, Weeks L, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:467–73.

Carletto C, Zezza A, Banerjee R. Towards better measurement of household food security: harmonizing indicators and the role of household surveys. Glob Food Sec. 2013;2:30–40.

FAO, IFAD, WFP. The state of food insecurity in the world 2013. The multiple dimensions of food security: 16. Rome: FAO; 2013.

Manikas I, Ali BM, Sundarakani B. A systematic literature review of indicators measuring food security. Agric Food Secur. 2023;12:10.

Doustmohammadian A, Mohammadi-Nasrabadi F, Fadavi G. COVID-19 pandemic and food security in different contexts: a systematic review protocol. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(9):e0273046.

Rathbone J, Carter M, Hoffmann T, Glasziou P. Better duplicate detection for systematic reviewers: evaluation of systematic review assistant-deduplication module. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1):6.

Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle–Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25(9):603–5.

FAO. Afghanistan | Agricultural livelihoods and food security in the context of COVID-19: monitoring report. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization; 2021.

FAO. Somalia | Agricultural livelihoods and food security in the context of COVID-19: monitoring report. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization; 2021.

FAO. Yemen | Agricultural livelihoods and food security in the context of COVID-19: monitoring Report. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization; 2021.

FAO. The Sudan | Food supply, agricultural livelihoods and food security in the context of COVID-19: monitoring Report. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization; 2021.

Breisinger C, Raouf M, Wiebelt M, Kamaly A, Karara M. Impact of COVID-19 on the Egyptian economy: economic sectors, jobs, and households. In: Regional Program Policy Note 06. Cairo: International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI); 2020.

ElKadhi Z, Elsabbagh D, Frija A, Lakoud T, Wiebelt M, Breisinger C. The impact of COVID-19 on Tunisia’s economy, agri-food system, and households. In: MENA Policy Note IFPRI; 2020.

Elsabbagh D, Kurdi S, Wiebelt M. Impact of COVID-19 on the Yemeni Economy. How the drop in remittances affected economic sectors, food systems, and households. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI); 2021.

Raouf M, Elsabbagh D, Wiebelt M. Impact of COVID-19 on the Jordanian economy: Economic sectors, food systems, and households. In: MENA Policy Note 9. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI); 2020.

IOM, WFP. Hunger and COVID-19 in Libya: a joint approach examining the food security situation of migrants. Libya: International Organization for Migration (IOM), UKaid, World Food Programme (WFP); 2021.

CARE. Impact of COVID 19 on food security, gender equality, and sexual and reproductive health in Yemen. Aden: CARE; 2021.

Breisinger C, Raouf M, Wiebelt M, Kamaly A, Karara M. COVID-19 and the Egyptian Economy From reopening to recovery: alternative pathways and impacts on sectors, jobs, and households. In: REGIONAL PROGRAM POLICY NOTE 06. Cairo, Egypt: A joint note by the International Food Policy Research Institute and the Ministry of Planning and Economic Development of the Government of the Arab Republic of Egypt; 2020.

Pakravan-Charvadeh MR, Gholamrezai S, Vatanparast H, Flora C, Nabavi-Pelesaraei A. Determinants of household vulnerability to food insecurity during COVID-19 lockdown in a mid-term period in Iran. Public Health Nutr. 2021;24(7):1619–28.

Movahed RG, Fard FM, Gholamrezai S, Pakravan-Charvadeh M. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on food security and food diversity of Iranian rural households. Front Public Health. 2022;10:862043.

Elsahoryi N, Al-Sayyed H, Odeh M, McGrattan A, Hammad F. Effect of Covid-19 on food security: a cross-sectional survey. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2020;40:171–8.

AlTarrah D, AlShami E, AlHamad N, AlBesher F, Devarajan S: The Impact of Coronavirus COVID-19 Pandemic on Food Purchasing, Eating Behavior, and Perception of Food Safety in Kuwait. Sustainability 2021, 13.

Kharroubi S, Naja F, Diab-El-Harake M, Jomaa L. Food insecurity pre- and post the COVID-19 pandemic and economic crisis in Lebanon: prevalence and projections. Nutrients. 2021;13:2976.

Bilali HE, Hassen TB, Chatti CB, Abouabdillah A, Alaoui SB. Exploring household food dynamics during the COVID-19 pandemic in Morocco. Front Nutr. 2021. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2021.724803.

Hasse TB, Bilali HE, Allahyari MS, Samman HA, Marzban S. Observations on food consumption behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic in Oman. Front Public Health. 2022;9:779654.

Ben-Hassen T, El-Bilali H, Allahyari MS. Impact of COVID-19 on food behavior and consumption in Qatar. Sustainability. 2020;12(17):6973.

Almoraie NM, Hanbazaza MA, Aljefree NM, Shatwan IM. Nutrition-related knowledge and behaviour and financial difficulties during the COVID-19 quarantine in Saudi Arabia. Open Public Health J. 2021;14:24–31.

New World Bank country classifications by income level: 2022–2023

FAO. The state of food security in the Near East and North Africa. Rome: FAO Regional Conference for the Near East; 2022.

Mandour DA. Covid-19 and food security challenges in the MENA region. Cairo: Economic Research Forum; 2021.

Onyeaka H, Tamasiga P, Nkoutchou H, Guta AT. Food insecurity and outcomes during COVID-19 pandemic in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). Agric Food Secur. 2022;11:56–68.

Aljaraedah T, Takruri H, Tayyem R. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on food and nutrition security and dietary habits among Syrian refugees in camps: a general review. Curr Res Nutr Food Sci. 2023;11(1):22–36.

IFPRI. 2021 Global food policy report: transforming food systems after COVID-19. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute; 2021.

Mishra A, Choudhary M, Das TR, Saren P, Bhattacherjee P, Thakur N, Tripathi SK, Upadhaya S, Kim H-S, Murugan NA. Sustainable chemical preventive models in COVID-19: understanding, innovation, adaptations, and impact. J Indian Chem Soc. 2021;98(10):100164.

Thakur N, Nigam M, Tewary R, Rajvanshi K, Kumar M, Shukla SK, Mahmoud GA-E, Gupta S. Drivers for the behavioural receptiveness and non-receptiveness of farmers towards organic cultivation system. J King Saud Univ-Sci. 2022;34(5):102107–11.

Bloem JR, Farris J. The COVID-19 pandemic and food security in low- and middle-income countries: a review. Agric Food Secur. 2022;11:55.

Mugabe PA, Renkamp TM, Rybak C, Mbwana H, Gordon C, Sieber S, Löhr K. Governing COVID-19: analyzing the effects of policy responses on food systems in Tanzania. Agric Food Secur. 2022;11:47.

Swinnen J, McDermott J. COVID-19 and global food security. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI); 2020.

Mohammadi-Nasrabadi F. Local solutions for global target of sustainable food and nutrition. Iran J Nutr Sci Food Technol. 2018;13(1):S182.

Rezazadeh A, Nasrabadi FM. The importance of traditional dietary patterns and local foods for promoting household food and nutrition security. Iran J Nutr Sci Food Technol. 2017;12(1):S164.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank National Nutrition and Food Technology Research Institute) for their support in developing the search strategy and dear researchers who made this review possible with their valuable studies.

Funding

This review is funded by the National Nutrition and Food Technology Research Institute, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (Grant No. 99-23953).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AD, FMN, and GF conceived and designed the study. AD, FMN, SA, and MHS developed the search strategy. AD and FMN extracted the data. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the ethics committee of the National Nutrition and Food Technology Research Institute, Shahid Beheshti, University of Medical Sciences (No: IR.SBMU.NNFTRI.REC.1399.041).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1

. Database search strategy.

Additional file 2: Table S2

. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) Checklist.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Doustmohammadian, A., Fadavi, G., Alibeyk, S. et al. An overview of food insecurity during the global COVID-19 outbreak: transformative change and priorities for the Middle East. Agric & Food Secur 12, 40 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40066-023-00448-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40066-023-00448-y