Abstract

Achieving gender equality and women’s empowerment in food systems can result in greater food security and better nutrition, as well as more just, resilient and sustainable food systems for all. This chapter uses a scoping review to assess the current evidence on pathways between gender equality, women’s empowerment and food systems. The chapter uses an adaptation of the food system framework to organize the evidence and identify where evidence is strong, and where gaps remain. Results show strong evidence on women’s differing access to resources, shaped and reinforced by contextual social gender norms, and on links between women’s empowerment and maternal education and important outcomes, such as nutrition and dietary diversity. However, evidence is limited on issues such as gender considerations in food systems for women in urban areas and in aquaculture value chains, best practices and effective pathways for engaging men in the process of women’s empowerment in food systems, and how to address issues related to migration, crises and indigenous food systems. While there are gender-informed evaluation studies examining the effectiveness of gender- and nutrition-sensitive agricultural programs, evidence indicating the long-term sustainability of such impacts remains limited. The chapter recommends key areas for investment: improving women’s leadership and decision-making in food systems, promoting equal and positive gender norms, improving access to resources, and building cross-contextual research evidence on gender and food systems.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Women are key actors in food systems as producers, wage workers, processors, traders, and consumers. They do this work despite many constraints and limitations, including lower access to opportunities, technologies, finance and other productive resources, and weak tenure and resource rights. These constraints and limitations are shaped and reinforced by social and structural inequalities in food systems. Stark gender inequalities are both a cause and outcome of unsustainable food systems and unjust food access, consumption and production. In the agriculture sector, for example, evidence shows that women have unequal access, and, in some cases, unequal rights, to important resources, such as land, water, pasture, seeds, fertilizers, chemical inputs, technology and information, and extension and advisory services, all of which reduces their potential to be productive in agriculture, become empowered to make strategic decisions and act on those decisions, and realize their rights (Doss 2018; Meinzen-Dick et al. 2019a, b; Mulema and Damtew 2016; Madzorera and Fawzi 2020). In addition, compared with men, women are more vulnerable to chronic food and nutrition insecurity, as well as shock-induced food insecurity (Madzorera and Fawzi 2020; Theis et al. 2019).

2 Conceptual Framing

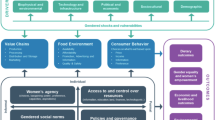

We conceptualize gender as an important lever for progress across all aspects of food systems (Fig. 1) and draw upon key terms and definitions of women’s empowerment, women’s economic empowerment, and gender-transformative approaches (see definitions in Annex). Food system drivers are anchored in a gendered system with structural gender inequalities and are shaped by shocks and vulnerabilities that affect men and women in different ways. Structural gender inequalities and gendered shocks and vulnerabilities thus influence the ways in which men and women experience these drivers of food systems, which, in turn, shape the three main components of food systems: value chains, the food environment, and consumer behavior.

Gendered food systems. (Source: Adapted from de Brauw et al. 2019)

This conceptualization of gender in food systems recognizes and highlights the linkages and interconnectedness across these three components. For example, strengthened access to nutritious foods (food environment) is an important source and pathway to strengthening individual and household resilience (drivers), particularly as adverse effects of climate change will continue to negatively influence access to and consumption of diverse nutrient-rich foods (Fanzo et al. 2018; Theis et al. 2019). And, as food systems are both contributors to and impacted by climate change, nature-positive production schemes (production), such as sustainable agricultural intensification strategies, enable food systems to reduce their contribution to and mitigate the impacts of climate change, thus strengthening resilience (drivers) (Campbell et al. 2014).

These three components of the food system interact with gender equality/inequality in a four-dimensional space: individual and systemic, formal and informal. Transforming food systems in equitable ways requires changes in gender equality at the individual and systemic levels and at the formal and informal levels. Changes must occur in: women’s and men’s consciousness, capacity, behavior and awareness (individual; informal); access to resources, services and opportunities (individual, formal); informal and implicit cultural norms, deep structure and the social values that undergird the way in which institutions operate(informal, systemic); and in formal policies, laws, and institutional arrangements (formal, systemic) in place to protect against social and gender discrimination and advance equality (Gender at Work n.d.). Change must go beyond simply reaching women through interventions, and requires facilitating the empowerment process so that women can benefit from food system activities (namely, increasing wellbeing, food security, income, and health) and can make and act upon strategic life decisions within food systems.Footnote 1 Women’s agency, differences in access to and control over resources, gendered social norms, and existing policies and governance influence how men and women can participate in and benefit from food systems, leading to differences in overall outcomes (Fig. 1).

3 Methodology

This chapter uses a scoping review (Harris et al. 2021; Liverpool-Tasie et al. 2020) to assess the current evidence on gender issues in food systems. Given the broad range of key topics related to gender in food systems, topically relevant and published systematic reviews were purposively sampled to provide a baseline state of the evidence. After purposively sampling and identifying 16 systematic and scoping reviews to inform the baseline, additional articles were collected. Three databases (Google Scholar, ScienceDirect, and IFPRI’s Ebrary) were used to gather and collect additional articles using key word searches aligned with 42 unique terms cross-referenced with the terms “gender” and “women.” A total of 198 articles were selected from these databases for review after meeting the following inclusion criteria: the articles had to be empirical and peer-reviewed, published in English, and have a geographic focus in low- or middle-income countries (LMICs). The article also had to make an explicit reference to gender or women’s empowerment and the key thematic term. For articles meeting these initial criteria, additional criteria were used to exclude some from the review, including if the methodology was inadequate to account for biases, or if the article was not relevant to agriculture or food systems. Duplicate articles from across the searches were eliminated from the database. Finally, additional articles were identified for inclusion from the citations in the articles collected above. All collected articles were managed in Zotero reference manager software.Footnote 2

4 Findings

This section presents the main findings of evidence relevant to the components of the gendered food system conceptual framework (Fig. 1): drivers and cross-cutting levers, shocks and stressors, food and value chains, food environment, consumer behavior, and outcomes.

In general, the evidence reveals that women are important actors and contributors to food systems, but their contributions are typically undervalued, unpaid, or overlooked in food systems research. A 2021 map of food systems and nutrition evidence from the International Initiative for Impact Evaluation (3ie) indicates that, although women have a major role in food systems, relatively few studies have examined strategies for or the effectiveness of interventions aimed at improving women’s decision-making power or have measured outcomes related to empowerment (Moore et al. 2021). Many food system interventions have not collected evidence regarding gender, an oversight that may result in poor outcomes or the inefficient use of funds to improve food systems (Moore et al. 2021).

Overall, the literature is largely in agreement as to how to advance gender equality and women’s empowerment in food systems, but offers little evidence on causal pathways or mechanisms (Moore et al. 2021). The existing evidence, in general, offers locally or contextually specific findings; limited evidence exists that applies across contexts or at a geographic scale.Footnote 3

4.1 Drivers: Shocks and Stressors

Men and women are differently exposed and vulnerable to shock and stress events. As a result of social norms and differing access to important resources, men and women have different capacities to mitigate risk and respond to these events (Mahajan 2017; Codjoe et al. 2012). The types of capacities needed include absorptive, adaptive, and transformative capacities, which are built by developing and leveraging resources and networks to reduce the risk of adverse impacts and facilitate faster recovery from shock and stress events. Gendered impacts of shocks are nuanced, context-specific, and often unexpected (Quisumbing et al. 2018; Rakib and Matz 2014; Nielsen and Reenberg 2010). Gendered perceptions of climate change and ensuing effects are based on livelihood activities and household and community roles and responsibilities, and often influence how men and women can leverage adaptation strategies to respond (Quisumbing et al. 2018; Aberman et al. 2015; Nielsen and Reenberg 2010).

Many studies indicate that gender-differentiated access to or ownership of important resources—such as women having fewer assets and lacking access to information services or credit—is linked to different capacities to mitigate, adapt to, and recover from shock and stress events (Bryan et al. 2013; de Pinto et al. 2020; Fisher and Carr 2015). However, women’s participation in collaborative farming schemes or group networks facilitates broader access to resources and additional social networks and types of social capital, which strengthen women’s capacity to respond to these events (Vibert 2016). For example, participation in community groups and access to credit options in Mali have been positively associated with an uptake in climate-smart agriculture practices and technologies (Ouédraogo et al. 2019).

Women have fewer adaptation options than men, as social norms restrict women’s mobility, freedom of movement, and access to transportation, as do time burdens associated with domestic and care responsibilities (Jost et al. 2016; Naab and Koranteng 2012; de Pinto et al. 2020). However, de Pinto et al. (2020) note evidence that certain components of women’s empowerment led to increased crop diversification among small-scale agricultural producers in Bangladesh, suggesting that women do play an important and positive role in climate change adaptation. Access to context-specific and relevant climate information and appropriate technologies is a key determinant of adopting climate change adaptation practices, and women and men have different needs for and access to such information (see section below on Gendered Access to Services and Technology) (Bryan et al. 2013; Tambo and Abdoulaye 2012; Twyman et al. 2014; Mudege et al. 2017).

4.2 Food System Components

4.2.1 Agrifood Value Chains

Women are actively engaged across various roles in agricultural value chains, although women’s positions are typically undervalued and overlooked in food systems research (Doss 2013). In Ethiopia, Abate (2018) found that women were predominately responsible for storage preparation, post-harvest processing, milk processing, barn cleaning, care for newborn livestock, cooking, grinding, fetching, and collecting fuelwood, and worked with men to weed, harvest, thresh, and protect crops from wildlife. Qualitative evidence from Benin suggests that women are predominately engaged in agricultural processing activities and, if they have access to land, are also engaged in production activities (Eissler et al. 2021a). Studies from Benin and Tanzania also found that, regardless of the producer, men manage higher-value sales and marketing, while women only manage the marketing and negotiation of small-value sales (Eissler et al. 2021a; Mwaseba and Kaarhus 2015). Gupta et al. (2017) provided evidence that improving women’s market access is strongly correlated with increased levels of women’s empowerment in India.

Agriculture both contributes to and is affected by anthropogenic climate change. As population pressures continue to increase and place demands on food production, agricultural livelihoods across agrifood value chains must adapt approaches that will sustainably meet rising demand, reduce risk associated with adverse climatic events, and mitigate contributions to climate change. Such approaches include sustainable intensification (Tilman et al. 2011; Rockström et al. 2017), conservation agriculture (Montt and Luu 2020), and climate-smart and climate-resilient agriculture (Gutierrez-Montes et al. 2020; Duffy et al. 2020), among others. A growing body of evidence indicates that women producers are less able to adopt such sustainable and resilient production practices or methods given their limited access to necessary resources, including land, time, labor, information, and technologies (Theriault et al. 2017; Ndiritu et al. 2014; Grabowski et al. 2020; Farnworth et al. 2016; Meinzen-Dick et al. 2019a, b; Doss et al. 2015; Perez et al. 2015; Pradhan et al. 2019; Parks et al. 2015; Ayantunde et al. 2020; Khoza et al. 2019; Gathala et al. 2021; Montt and Luu 2020; Beuchelt and Badstue 2013; Halbrendt et al. 2014).

4.2.2 Food Environment

Several themes emerge from the evidence linking gender equality and women’s empowerment with improving the availability of and access to safe and nutritious food. First, the affordability of nutritious food is an important issue for accessing nutrient-rich foods to advance gender equality and women’s empowerment. Available evidence indicates that women are less likely than men to be able to afford a nutritious diet, as women often occupy lower-paying wage positions than men, earn and control smaller incomes than men, have less autonomy over household financial decisions, or have no income at all. For example, Raghunathan et al. (2021) estimated that, while nutritious diets have become substantially more affordable for both female and male wage workers in rural India, unskilled wage workers still cannot afford a nutritious diet; unskilled workers account for approximately 80–90% of female and 50–60% of male daily wage workers, and care for 63–76% of poor rural children.

Another important theme is ensuring equitable access to markets where nutritious foods can be purchased. Nutrient-dense foods, such as fruit, milk and vegetables, are difficult to transport and store, and therefore must be purchased locally, particularly in remote and rural areas (Hoddinott et al. 2015; Mulmi et al. 2016). Several articles linked women’s mobility and freedom of movement to market access, and thus to positive nutrition and food security outcomes. For example, Aryal et al. (2019) found that physical distance to markets impacted household food security outcomes for female-headed households more than for male-headed households in Bhutan. Shroff et al. (2011) found women’s low autonomy in mobility was positively associated with wasting in children in India. The evidence seems to associate women’s limited mobility with stricter social gender norms and religion.

4.2.3 Consumer Behavior

Agriculture can influence diets and dietary choices through the consumption of household-produced crops or increased purchasing power derived from the sale of agricultural products. Moore et al. (2021) found that, in research carried out since 2000, women’s roles in food systems have mostly been examined in terms of their role as consumers, such as household cooks, or as mothers who are breastfeeding or whose health affects that of their children. Other studies link gender norms, roles and responsibilities to women as food preparers and managers of the quality of household diets (Eissler et al. 2020a; Sraboni and Quisumbing 2018). Komatsu et al. (2018) found a positive association between the amount of time women spent on food preparation and household dietary diversity, and Chaturvedi et al. (2016) found a positive association between the time mothers spent with their children and nutrition status.

There is evidence showing positive effects of nutrition counseling, nutrition education, and maternal education for nutrition, dietary diversity, and health outcomes for women and children (Choudhury et al. 2020; Akter et al. 2020; Kimambo et al. 2018; Reinbott and Jordan 2016; Reinbott et al. 2016; Rakotomanana et al. 2020; Ragasa et al. 2019). Interventions for sustainable and nutritious diets are found to be more effective when they include components on nutrition and communication about health behavior change, women’s empowerment, water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH), and micronutrient-fortified products (Ruel et al. 2018). Gelli et al. (2017) found preliminary evidence that WASH components of a nutrition-sensitive agriculture intervention in Burkina Faso may have mitigated the potential harm, such as the health risks, of introducing and enhancing small livestock production. However, more evidence is needed to understand the best practices for reducing potential harm of increased livestock production and management in nutrition-sensitive agricultural programs (Ruel et al. 2018).

4.3 Food System Outcomes

Recent research has examined the link between maternal mental health and psychosocial indicators and nutrition outcomes. There is mixed evidence regarding the link between maternal depression and mental health symptoms and child or household nutrition. Wemakor and Iddrisu (2018) found no association between maternal depression and child stunting in northern Ghana, whereas Wemakor and Mensah (2016) and Anato et al. (2020) found positive associations between women experiencing depressive symptoms and child undernutrition in Ghana and Ethiopia. Wemakor and Mensah (2016) observed that women experiencing the highest levels of depression were also those with the lowest incomes or from the lowest-income households. Cetrone et al. (2020) found that food security improvements resulting from participation in a nutrition-sensitive agriculture program mediated women’s depression symptoms in Tanzania. Such evidence, which is both mixed and limited, suggests that further studies are needed to understand the psychosocial impacts of women’s empowerment and mental health on household nutrition and health outcomes.

Evidence links access to resources and empowerment to outcomes in nutrition and children’s education. For example, evidence indicates that female livestock ownership or production diversity, combined with market access and women’s empowerment, are important drivers of diverse household consumption and nutritional status (Sibhatu et al. 2015; Mulmi et al. 2016; Hoddinott et al. 2015). Additionally, Malapit et al. (2019) found in Bangladesh that, while gaps in parental empowerment had only weak associations with children’s nutrition status, mother’s empowerment is positively associated with girls’ education and keeping older children in school in general.

A growing body of research has examined the pathways through which women’s empowerment is linked with household nutrition outcomes and access to nutritious foods (Alaofè et al. 2017; Reinbott and Jordan 2016; Bellows et al. 2020; Malapit and Quisumbing 2015; Heckert et al. 2019; Lentz et al. 2019). These pathways are contextual and vary across countries and regions (Na et al. 2015; Ruel et al. 2018; Quisumbing et al. 2021). Ruel et al. (2018) observe that, while the current evidence broadly associates women’s empowerment and nutrition outcomes, this evidence is generally context-specific, given that women’s empowerment and gender roles and norms are closely linked. As more evidence is generated from cross-context evaluations, future research can create typologies to better explain how gender roles more broadly interact with nutrition-sensitive agricultural interventions (Ruel et al. 2018).

Specific to equitable livelihood outcomes, evidence indicates that women face disproportionate barriers in accessing finance and credit options compared with men (Adegbite and Machethe 2020; Ghosh and Vinod 2017; Dawood et al. 2019; Kabir et al. 2019). For example, Kabir et al. (2019) found that in Bangladesh, a lack of access to credit is the most significant barrier women producers faced, followed by a lack of need-based training, high interest rates, insufficient land access, and a lack of quality seeds. Women’s ability to earn incomes and participate in income-generating activities is strongly mediated by restrictive gender norms, a lack of access to resources, and time burdens arising from normative roles and responsibilities. In a study of urban women vegetable traders in Viet Nam, Kawarazuka et al. (2017) found that women were able to work in less socially respected spaces, such as street trading, but still needed to negotiate their access to informal employment spaces with their husbands.

Supporting women’s entrepreneurship is suggested as an important pathway to advancing gender equality and women’s empowerment in food systems. Malapit et al. (2019) suggest that this is not necessarily the case if these businesses are small and home-based; such businesses typically make little profit and tend to add to women’s existing time burdens. And in a systematic literature review, Wolf and Frese (2018) emphasized the need to recognize that spousal support is a key factor for women’s entrepreneurship or engagement in income-generating activities.

5 Cross-Cutting Gender and Food System Issues

5.1 Gendered Social Norms and Expectations

Social and cultural norms shape and reinforce the ways in which women and men can participate in, access, and benefit from opportunities and resources (Kristjanson et al. 2017; Meinzen-Dick et al. 2019a, b; Rao et al. 2019; Moosa and Tuana 2014). This has important consequences across all aspects of advancing women’s empowerment and gender equality in food systems. For example, norms can hinder women’s ability to access or adopt new agricultural practices (Kiptot and Franzel 2012; Njuki et al. 2014). Importantly, gender norms vary within contexts, such as by religious identity or social class. Kruijssen et al. (2016) noted that different normative expectations of women in Hindu and Muslim communities in Bangladesh influenced the ways in which these women were constrained or enabled in participating in aquaculture value chains.

In general, women often experience restrictive social norms that hinder their empowerment and full participation in household or community activities and value chains (Huyer and Partey 2020; Kruijssen et al. 2018). In a review of evidence on gender issues in global aquaculture value chains, Kruijssen et al. (2018) found that contextual gender norms shape the ways in which women and men participate in aquaculture value chains around the world, often limiting women’s ability to participate in and benefit from aquaculture value chains equally.

Social gender norms are contextually and culturally specific and are strongly linked to women’s empowerment (Eissler et al. 2020a, b, 2021a; Meinzen-Dick et al. 2019a, b; Bryan and Garner 2020). Emic understandings of an empowered woman and an empowered man vary, but importantly inform the understanding of cultural nuances and expectations of the roles and responsibilities of women (Meinzen-Dick et al. 2019a, b; Bryan and Garner 2020). Men are generally considered to be the household financial providers and decision-makers, whereas women are responsible for domestic chores, childcare, food preparation, and other unpaid care tasks. In rural agricultural settings, women may also provide household labor on their husbands’ agricultural plots in addition to their domestic work, yet are not remunerated for this labor (Picchioni et al. 2020; Nahusenay 2017; Ghosh and Chopra 2019). Recent evidence also suggests that patterns of male dominance in the household are linked to individuals’ gender norms, but are not necessarily correlated with intergenerational transfers of male dominance in intrahousehold decision-making (Leight 2021).

5.2 Gendered Access to and Control over Resources, Services and Technology

A large body of literature has examined differences in men’s and women’s access to, ownership of, and control over resources in the food system (Johnson et al. 2016; Uduji et al. 2019; Perez et al. 2015; Gebre et al. 2019; Fisher and Carr 2015; Lambrecht and Mahrt 2019). Evidence indicates that perceived or effective ownership of resources may be more important than actual ownership for women’s empowerment and nutrition outcomes (Eissler et al. 2020b). Studies have found positive associations between women’s land ownership and their participation in community groups or co-operative networks, suggesting that access to important resources, such as land, facilitates access to other resources, such as increased bargaining power and pooled assets. Further evidence indicates that when women’s previously less lucrative or lower-valued activities begin to rise in value or earn higher incomes, control over the activity or resource may be transferred from women to men (Mwaseba and Kaarhus 2015).

Existing literature shows that women face social, cultural and institutional barriers to accessing and adopting agricultural technologies, information and services (Peterman et al. 2014; Peterman et al. 2011; Perez et al. 2015; Mudege et al. 2017; Ragasa et al. 2013; de Pinto et al. 2020; Raghunathan et al. 2019; Duffy et al. 2020). Men and women have different needs for and access to such information and technologies; gender analyses are therefore needed to tailor communication strategies so as to ensure that information and dissemination are adequately targeted towards men and women (Tall et al. 2014; Peterman et al. 2014; Diouf et al. 2019; Ragasa et al. 2013; Jost et al. 2016; Mudege et al. 2017; Duffy et al. 2020). Women have access to disproportionately less information than men overall, but they have access to more information regarding certain topics relevant to their gender-normative roles and responsibilities, such as post-harvest handling and small livestock production (Twyman et al. 2014).

Gender-sensitive program designs that aim to increase access to technologies have positive impacts on women’s nutrition and health outcomes (Kassie et al. 2020; Alaofè et al. 2016a, b, 2019). An evaluation of a gender-sensitive irrigation intervention in northern Benin found that women in the program had higher dietary diversity, increased intake of vegetables, reduced rates of anemia, higher body mass indexes (BMI), and improved household nutritional status through direct consumption as a result of women’s increased crop diversification and increased income that allowed them to make economic decisions (Alaofè et al. 2016a, b, 2019).

Interventions to benefit or empower women may overlook the time trade-offs required for women’s participation or for intended outcomes (Picchioni et al. 2020; Komatsu et al. 2018; van den Bold et al. 2021). Importantly, measuring time use itself does not address women’s agency over said time use or the intrahousehold decision-making surrounding how and on what activities women may spend their time (Eissler et al. 2021b). There is little research to show how women can control their own time use or how interventions can support women in managing their own time to advance their strategic choices in food systems.

5.3 Women’s Agency: Decision-Making and Leadership

5.3.1 Household Level

Evidence suggests that there are positive nutrition, livelihood, wellbeing, and resilience outcomes when women are more involved and have greater influence in household decision-making. Several studies find that when women own or have joint title to land, they are significantly more involved or have greater influence in household decision-making, particularly regarding agricultural or productive decisions (Wiig 2013; Mishra and Sam 2016). And while Fisher and Carr (2015) found that women farmers in Ghana and Malawi were less likely to adopt drought-tolerant maize varieties due to differences in resource access, women strongly influenced the adoption of drought-tolerant maize varieties on plots controlled by their husbands.

5.3.2 Community Level

Diiro et al. (2018) found evidence that increases in women’s empowerment, including women’s participation in community leadership, is associated with higher agricultural productivity; and women from more food-secure households are more likely to participate in community leadership roles. Niewoehner-Green et al. (2019) found that, for women in rural Honduras, social norms and structural biases hindered their participation in leadership positions in agricultural groups and limited their influence and voice in community decisions. There is some evidence to suggest that men and women value and participate in different types of community groups. For example, women place a higher value on savings and credit groups than men and may have greater access to hyper-local institutions, whereas men have greater access to institutions and services from outside of their immediate community (Cramer et al. 2016; Perez et al. 2015). Other evidence suggests that women may participate in fewer groups than men (Mwongera et al. 2014).

5.3.3 Food Systems Level

Increasing women’s voices and integrating their preferences into agricultural solutions, including technology design and implementation, is an under-researched pathway to empowerment and gender equality in food systems. For example, there is evidence that women may have different preferences than men with regard to crop varietals (Gilligan et al. 2020; Teeken et al. 2018), but there is limited evidence that breeders’ consider these preferences in varietal design and profiles (Tufan et al. 2018; Marimo et al. 2020).

5.4 Institutional Barriers, Policy, and Governance

The prevalence of gender-based violence (GBV) is a systemic barrier for women’s empowerment in food systems. There is extensive research in health literature on GBV; however, research on violence against women in the context of food systems is limited. Some studies find evidence that women’s asset ownership deters GBV, suggesting that when women own assets, their status may increase, making it easier for them to leave harmful relationships (Grabe 2010; Grabe et al. 2014). Buller et al. (2018) and Lees et al. (2021) found that cash transfer programs decrease the incidence of GBV. The new project-level Women’s Empowerment in Agriculture Index for Market Inclusion (pro-WEAI+MI) includes indicators on sexual harassment and violence against women in composite measurements of empowerment for women in agricultural value chains (Ragasa et al. 2021; Eissler et al. 2021a), providing a tool to measure the incidence of GBV and its impact on women’s empowerment in food systems.

Institutions and policies that support gender equality and women’s empowerment in food systems are generally lacking in low-income countries (Meinzen-Dick et al. 2013). Bryan et al. (2018) observed that a lack of policies and institutional capacity hinders research and gender integration into climate change adaptation programs across a range of contexts, specifically noting a lack of staff capacity on gender, a lack of funding to support gender integration, and sociocultural constraints as key barriers to gender integration. Some evidence suggests a tension between formal legislation and practiced law. Pradhan et al. (2019) found that, in practice, women’s joint and personal property rights differ from legal definitions. Eissler et al. (2021a) observed that, while Benin has formal gender equality and antidiscrimination laws, these are poorly enforced and do not align with social norms toward GBV or harassment. For example, women working in agricultural value chains often may not report incidents of sexual harassment in the workplace for fear of upsetting their husbands, suggesting that women may feel a sense of responsibility for inviting the harassment.

6 Conclusions

This scoping review aimed to elucidate evidence and identify evidence gaps for advancing gender equality and women’s empowerment in food systems. We see evidence that women have differing access to resources compared with men, such as essential services, knowledge and information, technology dissemination, land, credit options, time, and markets. This differing level of access is shaped and reinforced by contextual social gender norms. Existing evidence shows that context-specific pathways link women’s empowerment to important outcomes, such as household nutrition and dietary diversity, noting that these pathways may vary between and within contexts. Cross-contextual evidence exists of positive associations between maternal education (and specifically, access to nutrition education) and positive outcomes for child and household nutrition and diet quality.

While this review was not systematic, it appears that only limited studies address important areas of inquiry regarding gender equality and women’s empowerment in food systems. Specifically, only a few studies included in this review examined gender considerations in food systems for women in urban areas or aquaculture value chains. There have been few studies geared at understanding best practices and effective pathways for engaging men in the process of women’s empowerment in food systems, or addressing issues of migration, crises or indigenous food systems. Additionally, while there are gender-informed evaluation studies examining the effectiveness of gender- and nutrition-sensitive agricultural programs, there is limited evidence to indicate the long-term sustainability of such impacts.

In conclusion, this review suggests that there is substantial agreement about pathways to improve women’s empowerment and gender equality in food systems, but the actual evidence to support these pathways, specifically cross-contextual evidence, is limited. Existing evidence is extremely localized and context-specific, limiting its application beyond the focus area of the study. And finally, relatively few studies included a gender-informed design and conceptual framework to best understand mechanisms for promoting equality and empowerment. Moving forward, further research is required to produce stronger evidence on cross-contextual pathways to improve gender equality and women’s empowerment in food systems.

7 Recommendations for Investment

7.1 Invest in Maternal Education, Particularly Nutrition-Focused Education and Counseling

Cross-contextual evidence indicates that maternal education and experiences with nutrition counseling are positively associated with improved diet quality and diversity, leading to better nutrition outcomes at the household level. For example, Choudhury et al. (2019) found a positive association of maternal education and maternal health, household dietary diversity, and nutrition and health outcomes for household members in 42 countries, suggesting that dietary diversity may be driven by preferences and knowledge. In Tanzania, Kimambo et al. (2018) found positive associations between women’s nutrition knowledge and consumption of African vegetables. Rakotomanana et al. (2020) found that, in Madagascar, children of mothers with knowledge and positive attitudes about complementary nutrient-rich foods had more nutrient-diverse diets, while those with mothers who had lower incomes and greater time burdens had less nutrient-diverse diets. Studies also found benefits from involving grandmothers in nutrition counseling, education and dialogues in Sierra Leone (Aidam et al. 2020; MacDonald et al. 2020) and Nepal (Karmacharya et al. 2017). Investments should focus on increasing women’s educational attainment, coupled with nutrition-focused counseling.

7.2 Invest in Programs/Interventions that Aim to Improve Women’s Influence and Role in Decision-Making and Leadership at All Levels of the Food System (Household, Community, and Systems)

Women’s influence and role in decision-making is associated positively with nutrition, women’s empowerment, and livelihood outcomes at all levels of food systems. At the household level, in northern Ghana, for example, women are less likely to have decision-making autonomy over productive decisions, purchasing, selling or transferring assets, and speaking in public (Ragsdale et al. 2018). In Bangladesh, de Pinto et al. (2020) found that households have higher levels of crop diversification when women have more influence in productive household decision-making, suggesting that an increase in women’s bargaining power can lead to more resilient agricultural livelihoods. At the community level, evidence indicates that women’s participation in community groups also enhances resilience, increases access to important resources such as land and labor, builds and facilitates social networks, and increases their influence and participation in community-level decision-making (Kumar et al. 2019; Aberman et al. 2020). For example, Kabeer (2017) found that women in Bangladesh who expand their active social networks through community groups have higher levels of empowerment. Raghunathan et al. (2019) found that Indian women’s participation in self-help groups was positively associated with increased levels of information and participation in some agricultural decisions, but did not affect agricultural production or outcomes, possibly because of women’s limited time, financial constraints, or restrictive social norms. At the systems level, there is limited evidence to suggest that technology development (including crop breeding, for example) incorporates women’s different preferences and needs into design (Tufan et al. 2018; Marimo et al. 2020). Investments should be made in interventions that address and facilitate improvements for women’s influence and participation in decision-making at all levels.

7.3 Invest in Interventions that Promote Positive and Equal Gender Norms at the Household, Community, and Systems Levels

Gender norms and associated expectations vary by context; however, restrictive gender norms shape and, in many ways, hinder women’s empowerment across contexts and limit their ability to participate in and act upon strategic decisions or activities to advance their own empowerment across all components of food systems. For example, a study in Egypt found that a woman’s normative role as an unpaid household caregiver limited her ability to sell fish compared with her husband, who did not face time burdens associated with caregiving and who maintained decision-making control over his and his wife’s activities (Kantor and Kruijssen 2014). In Papua New Guinea, Kosec et al. (2021) found that men are more likely to support women challenging normative gender roles in terms of their economic participation during periods of household economic stress because this can raise household income, not because they support transforming women’s role in society more generally. Contextual gender norms may also shape women’s food allocation preferences, which hold important implications for nutrition. In Ethiopia, for example, women may favor sons over daughters for more nutrient-dense foods (Coates et al. 2018). Sraboni and Quisumbing (2018) found that women’s preferences in allocating nutritious foods were influenced heavily by social norms in Bangladesh, where women favored sons over daughters because of male advantage in labor markets and property rights. Investments should be made to promote positive and equal gender norms for and with men and women across contexts and scales from the household to system levels.

7.4 Invest in Interventions and Efforts that Improve Women’s Access to Important and Necessary Resources

The evidence overwhelmingly indicates that, across contexts, women have less access to important resources than men. These resources include, but are not limited to, land, agricultural inputs, financing options, financial services, technology, technical services, and time. Nuanced variations exist across and within contexts. For example, in sub-Saharan Africa, studies indicate that women may rely on informal sources of information, such as personal connections, whereas men rely on formal sources of information, such as extension or the private sector; however, in Colombia, men may have more access to information overall compared to women, but both rely on the same sources of information (Twyman et al. 2014; Mudege et al. 2017). With regard to time, Komatsu et al. (2018) found that women’s time allocation and household nutrition outcomes varied by local context, such that women’s time in domestic work was positively associated with diverse diets in Bangladesh, Cambodia, Ghana, Mozambique and Nepal, but in Mozambique, the relation between women’s time in agricultural work and children’s diet quality varied with women’s asset poverty. Picchioni et al. (2020) found that, in India and Nepal, women and men participate equally in productive work that requires high levels of energy, but women shoulder most of the reproductive work at the expense of leisure opportunities. Van den Bold et al. (2021) found that a nutrition-sensitive agricultural intervention in Burkina Faso significantly increased the time women spent on agriculture and led to improved maternal and child nutrition outcomes, and that women’s increased time spent on agriculture did not have deleterious effects on their own or their children’s nutrition. Investments should be made to target improving women’s access to and control and ownership over such resources so as to ensure that they are able to effectively benefit from these resources.

7.5 Target Research to Yield More Cross-Contextual Evidence for Advancing Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment in Food Systems

Finally, the overall outcome of this review revealed that the current evidence on advancing women’s empowerment and gender equality in food systems is locally specific and linked to contextual gender norms. Developing cross-contextual typologies can support the development of evidence that has broader application. More targeted research is required to identify patterns of successful and effective interventions and pathways to advance women’s empowerment and gender equality in food systems with contextual norms. The outcome of such research would be clear typologies that link successful interventions and recommendations by gender norms.

Notes

- 1.

See Johnson et al. (2018) for a discussion of the Reach-Benefit-Empowerment framework.

- 2.

All articles reviewed for this paper are compiled in a separate Excel database, with the following metrics collected for each article: author(s) name, article title, year published, journal or organization of publication, national focus (if specified), regional focus, methods used, and main finding(s). Additional information on the search methods and articles selected are included in the full review paper (citation forthcoming).

- 3.

The findings presented in this paper are high-level. A further, more nuanced explanation of the findings can be found in the full review paper (citation forthcoming).

References

Abate N (2018) An investigation of gender division of labour: the case of Delanta District, South Wollo Zone, Ethiopia. J Agric Ext Rural Dev 9(9):207–214

Aberman N, Ali S, Behrman J, Bryan E, Davis P, Donnelly A, Gathaara V, Kone D, Nganga T, Ngugi J, Okoba B, Roncoli C (2015) Climate change adaptation assets and group-based approaches: gendered perceptions from Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Mali, and Kenya, IFPRI discussion paper 01412. International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington, DC

Aberman N, Birner R, Odoyo EAO, Oyunga M, Okoba B, Okello G (2020) Gender-inclusive governance of ‘self-help’ groups in rural Kenya, IFPRI discussion paper 01986. International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington, DC

Adegbite O, Machethe C (2020) Bridging the financial inclusion gender gap in smallholder agriculture in Nigeria: an untapped potential for sustainable development. World Dev 127(March):104755

Aidam B, MacDonald C, Wee R, Simba J, Aubel J, Reinsma K, Girard A (2020) An innovative grandmother-inclusive approach for addressing suboptimal infant and young child feeding practices in Sierra Leone. Current Developments in Nutrition 4(12):nzaa174

Akter R, Yagi N, Sugino H, Thilsted SH, Ghosh S, Gurung S, Heneveld K, Shrestha R, Webb P (2020) Household engagement in both aquaculture and horticulture is associated with higher diet quality than either alone. Nutrients 12(9):2705

Alaofè H, Burney J, Naylor R, Taren D (2016a) Solar-powered drip irrigation impacts on crops production diversity and dietary diversity in Northern Benin. Food Nutr Bull 37(2):164–175

Alaofè H, Burney J, Naylor R, Taren D (2016b) The impact of a solar market garden programme on dietary diversity, women’s nutritional status and micronutrient levels in Kalalé District of Northern Benin. Public Health Nutr 22(14):2670–2681

Alaofè H, Zhu M, Burney J, Naylor R, Douglas T (2017) Association between women’s empowerment and maternal and child nutrition in Kalale District of Northern Benin. Food Nutr Bull 38(3):302–318

Alaofè H, Burney J, Naylor R, Taren D (2019) The impact of a solar market garden programme on dietary diversity, women’s nutritional status and micronutrient levels in Kalalé district of northern Benin. Public Health Nutr 22(14):2670–2681

Anato A, Baye K, Tafese Z, Stoecker BJ (2020) Maternal depression is associated with child undernutrition: a cross-sectional study in Ethiopia. Matern Child Nutr 16(3):e12934

Aryal JP, Rahut DB, Mottaleb KA, Ali A (2019) Gender and household energy choice using exogenous switching treatment regression: evidence from Bhutan. Environ Dev 30(June):61–75

Ayantunde AA, Oluwatosin BO, Yameogo V, van Wijk M (2020) Perceived benefits, constraints and determinants of sustainable intensification of mixed crop and livestock systems in the Sahelian Zone of Burkina Faso. Int J Agric Sustain 18(1):84–98

Bellows AL, Canavan CR, Blakstad MM, Mosha D, Noor RA, Webb P, Kinabo J, Masanja H, Fawzi WW (2020) The relationship between dietary diversity among women of reproductive age and agricultural diversity in rural Tanzania. Food Nutr Bull 41(1):50–60

Beuchelt TD, Badstue L (2013) Gender, nutrition- and climate-smart food production: opportunities and trade-offs. Food Secur 5(5):709–721

Bryan E, Garner E (2020) What does empowerment mean to women in northern Ghana? Insights from research around a small-scale irrigation intervention, IFPRI discussion paper 01909. International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington, DC

Bryan E, Ringler C, Okoba B, Roncoli C, Silvestri S, Herrero M (2013) Adapting agriculture to climate change in Kenya: household strategies and determinants. J Environ Manag 114(January):26–35

Bryan E, Bernier Q, Espinal M, Ringler C (2018) Making climate change adaptation programmes in sub-Saharan Africa more gender responsive: insights from implementing organizations on the barriers and opportunities. Clim Dev 10(5):417–431

Buller AM, Peterman A, Ranganathan M, Bleile A, Hidrobo M, Heise L (2018) A mixed-method review of cash transfers and intimate partner violence in low- and middle-income countries. World Bank Res Obs 33(2):218–258

Campbell B, Thornton P, Zougmoré R, van Asten P, Lipper L (2014) Sustainable intensification: what is its role in climate smart agriculture? Curr Opin Environ Sustain 8(October):39–43

Cetrone H, Santoso M, Petito L, Bezner-Kerr R, Blacker L, Kassim N, Mtinda E, Martin H, Young S (2020) A participatory agroecological intervention reduces women’s risk of probable depression through improvements in food security in Singida, Tanzania. Curr Dev Nutr 4(Supplement 2):819–819

Chaturvedi S, Ramji S, Arora NK, Rewal S, Dasgupta R, Deshmukh V (2016) Time-constrained mother and expanding market: emerging model of under-nutrition in India. BMC Public Health 16(July):632

Choudhury S, Headey DD, Masters WA (2019) First foods: Diet quality among infants aged 6–23 months in 42 countries. Food Policy 88:101762.

Choudhury S, Shankar B, Aleksandrowicz L, Tak M, Green R, Harris F, Scheelbeek P, Dangour A (2020) What underlies inadequate and unequal fruit and vegetable consumption in India? An exploratory analysis. Glob Food Sec 24(March):100332

Coates J, Patenaude BN, Rogers BL, Roba AC, Woldetensay YK, Tilahun AF, Spielman KL (2018) Intra-household nutrient inequity in rural Ethiopia. Food Policy 81(December):82–94

Codjoe S, Atidoh L, Burkett V (2012) Gender and occupational perspectives on adaptation to climate extremes in the Afram Plains of Ghana. Clim Chang 110(1):431–454

Cramer L, Förch W, Mutie I, Thornton PK (2016) Connecting women, connecting men: how communities and organizations interact to strengthen adaptive capacity and food security in the face of climate change. Gend Technol Dev 20(2):169–199

Dawood TC, Pratama H, Masbar R, Effendi R (2019) Does financial inclusion alleviate household poverty? Empirical evidence from Indonesia. Econ Soc 12(2):235–252

De Brauw A, van den Berg M, Brouwer I, Snoek H, Vignola R, Melesse M, Lochetti G, van Wagenberg C, Lundy M, d’Hotel E, Ruben R (2019) Food system innovations for healthier diets in low and middle-income countries, IFPRI discussion paper 01816. International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington, DC

De Pinto A, Seymour G, Bryan E, Bhandari P (2020) Women’s empowerment and farmland allocations in Bangladesh: evidence of a possible pathway to crop diversification. Clim Chang 163(2):1025–1043

Diiro GM, Seymour G, Kassie M, Muricho G, Muriithi BW (2018) Women’s empowerment in agriculture and agricultural productivity: evidence from rural maize farmer households in Western Kenya. PLoS One 13(5):e0197995

Diouf NS, Ouédraogo I, Zougmoré RB, Ouedraogo M, Partey ST, Gumucio T (2019) Factors influencing gendered access to climate information services for farming in Senegal. Gend Technol Dev 23(2):93–110

Doss C (2013) Intrahousehold bargaining and resource allocation in developing countries. World Bank Res Obs 28(1):52–78

Doss C (2018) Women and agricultural productivity: reframing the issues. Dev Policy Rev 36(1):35–50

Doss C, Kovarik C, Peterman A, Quisumbing A, van den Bold M (2015) Gender inequalities in ownership and control of land in Africa: myth and reality. Agric Econ 46(3):403–434

Duffy C, Toth G, Cullinan J, Murray U, Spillane C (2020) Climate smart agriculture extension: gender disparities in agroforestry knowledge acquisition. Clim Dev 13(January):1–13

Eissler S, Sanou A, Heckert J, Myers EC, Nignan S, Thio E, Pitropia LA, Ganaba R, Pedehombga A, Gelli A (2020a) Gender dynamics, women’s empowerment, and diets: qualitative findings from an impact evaluation of a nutrition-sensitive poultry value chain intervention in Burkina Faso, IFPRI discussion paper 01913. International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington, DC

Eissler S, Sanou A, Heckert J, Myers EC, Nignan S, Thio E, Pitropia LA, Ganaba R, Pedehombga A, Gelli A (2020b) Gendered participation in poultry value chains: qualitative findings from an impact evaluation of a nutrition-sensitive poultry value chain intervention in Burkina Faso, IFPRI discussion paper 01928. International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington, DC

Eissler S, Diatta A, Heckert J, Nordhen C (2021a) A qualitative assessment of a gender-sensitive agricultural training program in Benin: findings on program experience and women’s empowerment across key agricultural value chains, IFPRI discussion paper 02005. International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington, DC

Eissler S, Heckert J, Myers E, Seymour G, Sinharoy S, Yount KM (2021b) Exploring gendered experiences of time-use agency in Benin, Malawi, and Nigeria as a new concept to measure women’s empowerment, IFPRI discussion paper 02003. International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington, DC

Fanzo J, Davis C, McLaren R, Choufani J (2018) The effect of climate change across food systems: implications for nutrition outcomes. Glob Food Sec 18(September):12–19

Farnworth CR, Baudron F, Andersson JA, Misiko M, Badstue L, Stirling CM (2016) Gender and conservation agriculture in east and southern Africa: towards a research agenda. Int J Agric Sustain 14(2):142–165

Fisher M, Carr E (2015) The influence of gendered roles and responsibilities on the adoption of technologies that mitigate drought risk: the case of drought-tolerant maize seed in Eastern Uganda. Glob Environ Chang 35(November):82–92

Gathala MK, Laing AM, Tiwari TP, Timsina J, Rola-Rubzen F, Islam S, Maharjan S et al (2021) Improving smallholder farmers’ gross margins and labor-use efficiency across a range of cropping Systems in the Eastern Gangetic Plains. World Dev 138(February):105266

Gebre GG, Isoda H, Rahut DB, Amekawa Y, Nomura H (2019) Gender differences in agricultural productivity: evidence from maize farm households in southern Ethiopia. GeoJournal 86(November):843–864

Gelli A, Becquey E, Ganaba R, Headey D, Hidrobo M, Huybregts L, Verhoef H, Kenfack R, Zongouri S, Guedenet H (2017) Improving diets and nutrition through an integrated poultry value chain and nutrition intervention (SELEVER) in Burkina Faso: study protocol for a randomized trial. Trials 18(1):412

Gender at Work (n.d.) Gender at work framework. https://genderatwork.org/analytical-framework/

Ghosh A, Chopra D (2019) Paid work, unpaid care work and women’s empowerment in Nepal. Contemp South Asia 27(4):471–485

Ghosh S, Vinod D (2017) What constrains financial inclusion for women? Evidence from Indian micro data. World Dev 92(April):60–81

Gilligan D, Kumar N, McNiven S, Meenakshi J, Quisumbing A (2020) Bargaining power, decision making, and biofortification: the role of gender in adoption of orange sweet potato in Uganda. Food Policy 95(June):101909

Grabe S (2010) Promoting gender equality: the role of ideology, power, and control in the link between land ownership and violence in Nicaragua. Anal Soc Issues Public Policy 10(1):146–170

Grabe S, Grose R, Dutt A (2014) Women’s land ownership and relationship power: a mixed methods approach to understanding structural inequities and violence against women. Psychol Women Q 39(1):7–19

Grabowski PP, Djenontin I, Zulu L, Kamoto J, Kampanje-Phiri J, Darkwah A, Egyir I, Fischer G (2020) Gender- and youth-sensitive data collection tools to support decision making for inclusive sustainable agricultural intensification. Int J Agric Sustain. https://doi.org/10.1080/14735903.2020.1817656

Gupta S, Pingali PL, Pinstrup-Andersen P (2017) Women’s empowerment in Indian agriculture: does market orientation of farming systems matter? Food Secur 9(6):1447–1463

Gutierrez-Montes I, Arguedas M, Ramirez-Aguero F, Mercado L, Sellare J (2020) Contributing to the construction of a framework for improved gender integration into climate-smart agriculture projects monitoring and evaluation: MAP-Norway experience. Clim Chang 158(1):93–106

Halbrendt J, Kimura AH, Gray SA, Radovich T, Reed B, Tamang BB (2014) Implications of conservation agriculture for men’s and women’s workloads among marginalized farmers in the Central Middle Hills of Nepal. Mt Res Dev 34(3):214–222

Harris J, Tan W, Mitchell B, Zayed D (2021) Equity in agriculture-nutrition-health research: a scoping review. Nutr Rev. https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuab001

Heckert J, Olney DK, Ruel MT (2019) Is Women’s empowerment a pathway to improving child nutrition outcomes in a nutrition-sensitive agriculture program? Evidence from a randomized controlled trial in Burkina Faso. Soc Sci Med 233(July):93–102

Hillenbrand E, Karim N, Mohanraj P, Wu D (2015) Measuring gender-transformative change: a review of literature and promising practices, Working paper. CARE USA, Washington, DC

Hoddinott J, Headey D, Dereje M (2015) Cows, missing milk markets, and nutrition in rural Ethiopia. J Dev Stud 51(8):958–975

Huyer S, Partey S (2020) Weathering the storm or storming the norms? Moving gender equality forward in climate-resilient agriculture. Clim Chang 158(1):1–12

Johnson N, Kovarik C, Meinzen-Dick R, Njuki J, Quisumbing A (2016) Gender, assets, and agricultural development: lessons from eight projects. World Dev 83(July):295–311

Johnson N, Balagamwala M, Pinkstaff C, Theis S, Meinzen-Dick R, Quisumbing A (2018) How do agricultural development projects empower women? Linking strategies with expected outcomes. J Gend Agric Food Secur 3(2):1–19

Jost C, Kyazze F, Naab J, Neelormi S, Kinyangi J, Zougmoré R, Aggarwal P, Bhatta G, Chaudhury M, Tapio-Bistrom M, Nelson S, Kristjanson P (2016) Understanding gender dimensions of agriculture and climate change in smallholder farming communities. Clim Dev 8(2):133–144

Kabeer N (1999) Resources, agency, achievements: reflections on the measurement of women’s empowerment. Dev Chang 30(3):435–464

Kabeer N (2017) Economic pathways to Women’s empowerment and active citizenship: what does the evidence from Bangladesh tell us? J Dev Stud 53(5):649–663

Kabir MS, Marković MR, Radulović D (2019) The determinants of income of rural women in Bangladesh. Sustainability 11(20):5842

Kantor P, Kruijssen F (2014) Informal fish retailing in rural Egypt: opportunities to enhance income and work conditions for women and men. WorldFish, Penang

Karmacharya C, Cunningham K, Choufani J, Kadiyala S (2017) Grandmothers’ knowledge positively influences maternal knowledge and infant and Young child feeding practices. Public Health Nutr 20(12):2114–2123

Kassie M, Fisher M, Muricho G, Diiro G (2020) Women’s empowerment boosts the gains in dietary diversity from agricultural technology adoption in rural Kenya. Food Policy 95(August):101957

Kawarazuka N, Locke C, McDougall C, Kantor P, Morgan M (2017) Bringing analysis of gender and social–ecological resilience together in small-scale fisheries research: challenges and opportunities. Ambio 46(2):201–213

Khoza S, Van Niekerk D, Nemakonde LD (2019) Understanding gender dimensions of climate-smart agriculture adoption in disaster-prone smallholder farming communities in Malawi and Zambia. Disaster Preven Manag Int J 28(5):530–547

Kimambo J, Kavoi MM, Macharia J, Nenguwo N (2018) Assessment of factors influencing farmers’ nutrition knowledge and intake of traditional African vegetables in Tanzania. Afr J Food Agric Nutr Dev 18(2):13353–13371

Kiptot E, Franzel S (2012) Gender and agroforestry in Africa: a review of women’s participation. Agrofor Syst 84(1):35–58

Komatsu H, Malapit HJL, Theis S (2018) Does women’s time in domestic work and agriculture affect women’s and children’s dietary diversity? Evidence from Bangladesh, Nepal, Cambodia, Ghana, and Mozambique. Food Policy 79(August):256–270

Kosec K, Mo CH, Schmidt E, Song J (2021) Perceptions of relative deprivation and women’s empowerment. World Dev 138(February):105218

Kristjanson P, Bryan E, Bernier Q, Twyman J, Meinzen-Dick R, Kieran C, Ringler C, Jost C, Doss C (2017) Addressing gender in agricultural research for development in the face of a changing climate: where are we and where should we be going? Int J Agric Sustain 15(5):482–500

Kruijssen F, Rajaratnam S, Choudhury A, McDougall C, Dalsgaard JPT (2016) Gender in the farmed fish value chain of Bangladesh: a review of the evidence and development approaches, Program brief: 2016–38. WorldFish, Penang

Kruijssen F, McDougall C, van Asseldonk I (2018) Gender and aquaculture value chains: a review of key issues and implications for research. Aquaculture 493(1):328–337

Kumar N, Raghunathan K, Arrieta A, Jilani A, Chakrabarti S, Menon P, Quisumbing AR (2019) Social networks, mobility, and political participation: the potential for women’s self-help groups to improve access and use of public entitlement schemes in India. World Dev 114(February):28–41

Lambrecht I, Mahrt K (2019) Gender and assets in rural Myanmar: a cautionary tale for the analyst, IFPRI discussion paper 01894. International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington, DC

Lees S, Kyegombe N, Diatta A, Zogrone A, Roy S, Hidrobo M (2021) Intimate partner relationships and gender norms in Mali: the scope of cash transfers targeted to men to reduce intimate partner violence. Violence Against Women 27(3–4):447–469

Leight J (2021) Like father, like son, like mother, like daughter: intergenerational transmission of intrahousehold gender attitudes in Ethiopia. World Dev 142(June):105359

Lentz E, Narayanan S, De A (2019) Last and least: findings on intrahousehold undernutrition from participatory research in South Asia. Soc Sci Med 232(July):316–323

Liverpool-Tasie L, Wineman A, Young S, Tambo J, Vargas C, Reardon T, Adjognon G, Porciello J, Gathoni N, Bizikova L, Gaile A, Celestin A (2020) A scoping review of market links between value chain actors and small-scale producers in developing regions. Nat Sustain 3(October):799–808

MacDonald CA, Aubel J, Aidam BA, Girard AW (2020) Grandmothers as change agents: developing a culturally appropriate program to improve maternal and child nutrition in Sierra Leone. Curr Dev Nutr 4(1):nzz141

Madzorera I, Fawzi W (2020) Women empowerment is central to addressing the double burden of malnutrition. Clin Med 20(February):100286

Mahajan K (2017) Rainfall shocks and the gender wage gap: evidence from Indian agriculture. World Dev 91(March):156–172

Malapit HJL, Quisumbing AR (2015) What dimensions of women’s empowerment in agriculture matter for nutrition in Ghana? Food Policy 52(April):54–63

Malapit HJL, Sraboni E, Quisumbing AR, Ahmed AU (2019) Intrahousehold empowerment gaps in agriculture and children’s well-being in Bangladesh. Dev Policy Rev 37(2):176–203

Marimo P, Caron C, Van den Bergh I, Crichton R, Weltzien E, Ortiz R, Tumuhimbise R (2020) Gender and trait preferences for banana cultivation and use in Sub-Saharan Africa: a literature review. Econ Bot 74(2):226–241

Meinzen-Dick R, Bernier Q, Haglund E (2013) The six ‘ins’ of climate-smart agriculture: inclusive institutions for information, innovation, investment, and insurance, CAPRi working paper 114. International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington, DC

Meinzen-Dick R, Quisumbing A, Doss C, Theis S (2019a) Women’s land rights as a pathway to poverty reduction: framework and review of evidence. Agric Syst 172(June):72–82

Meinzen-Dick R, Rubin D, Elias M, Mulema AA, Myers E (2019b) Women’s empowerment in agriculture: lessons from qualitative research, IFPRI discussion paper 1797. International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington, DC

Mishra K, Sam AG (2016) Does Women’s land ownership promote their empowerment? Empirical evidence from Nepal. World Dev 78(February):360–371

Montt G, Luu T (2020) Does conservation agriculture change labour requirements? Evidence of sustainable intensification in Sub-Saharan Africa. J Agric Econ 71(2):556–580

Moore N, Lane C, Storhaug I, Franich A, Rolker H, Furgeson J, Sparling T, Snilstveit B (2021) The effects of food systems interventions on food security and nutrition outcomes in low- and middle-income countries, 3ie evidence gap map report 16. International Initiative for Impact Evaluation, New Delhi

Moosa CS, Tuana N (2014) Mapping a research agenda concerning gender and climate change: a review of the literature. Hypatia 29(3):677–694

Mudege NN, Mdege N, Abidin PE, Bhatasara S (2017) The role of gender norms in access to agricultural training in Chikwawa and Phalombe, Malawi. Gender Place Cult 24(12):1689–1710

Mulema A, Damtew E (2016) Gender-based constraints and opportunities to agricultural intensification in Ethiopia: a systematic review, ILRI project report. International Livestock Research Institute, Nairobi

Mulmi P, Block SA, Shively GE, Masters WA (2016) Climatic conditions and child height: sex-specific vulnerability and the protective effects of sanitation and food Markets in Nepal. Econ Hum Biol 23(December):63–75

Mwaseba DJB, Kaarhus R (2015) How do intra-household gender relations affect child nutrition? Findings from two rural districts in Tanzania. Forum Dev Stud 42(2):289–309

Mwongera C, Shikuku KM, Twyman J, Winowiecki LA, Ampaire EL, Koningstein M, Twomlow S (2014) Rapid rural appraisal report of northern Uganda. International Center for Tropical Agriculture/CGIAR research program on climate change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS), Cali-Palmira/Wageningen

Na M, Jennings L, Talegawkar SA, Ahmed S (2015) Association between women’s empowerment and infant and child feeding practices in sub-Saharan Africa: an analysis of demographic and health surveys. Public Health Nutr 18(17):3155–3165

Naab JB, Koranteng H (2012) Using a gender lens to explore farmers’ adaptation options in the face of climate change: results of a pilot study in Ghana, Working paper 17. CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security, Wageningen

Nahusenay A (2017) An investigation of gender division of labour: the case of Delanta district, South Wollo zone, Ethiopia. J Agric Ext Rural Dev 9(9):207–214

Ndiritu S, Kassie M, Shiferaw B (2014) Are there systematic gender differences in the adoption of sustainable agricultural intensification practices? Evidence from Kenya. Food Policy 49(1):117–127

Niewoehner-Green J, Stedman N, Galindo S, Russo S, Carter H, Colverson K (2019) The influence of gender on rural Honduran Women’s participation and leadership in community groups. J Int Agric Ext Edu 26(2):48–63

Njuki J, Waithanji E, Sakwa B, Kariuki J, Mukewa E, Ngige J (2014) Can market-based approaches to technology development and dissemination benefit women smallholder farmers? A qualitative assessment of gender dynamics in the ownership, purchase, and use of irrigation pumps in Kenya and Tanzania, IFPRI discussion paper 01357. International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington, DC

Østergaard Nielsen J, Reenberg A (2010) Cultural barriers to climate change adaptation: a case study from northern Burkina Faso. Glob Environ Chang 20(1):142–152

Ouédraogo M, Houessionon P, Zougmoré RB, Tetteh Partey S (2019) Uptake of climate-smart agricultural technologies and practices: actual and potential adoption rates in the climate-smart village site of Mali. Sustainability 11(17):4710

Parks MH, Christie ME, Bagares I (2015) Gender and conservation agriculture: constraints and opportunities in the Philippines. GeoJournal 80(1):61–77

Perez C, Jones EM, Kristjanson P, Cramer L, Thornton PK, Förch W, Barahona C (2015) How resilient are farming households and communities to a changing climate in Africa? A gender-based perspective. Glob Environ Chang 34(September):95–107

Peterman A, Quisumbing A, Behrman J, Nkonya E (2011) Understanding the complexities surrounding gender differences in agricultural productivity in Nigeria and Uganda. J Dev Stud 47(10):1482–1509

Peterman A, Behrman JA, Quisumbing AR (2014) A review of empirical evidence on gender differences in nonland agricultural inputs, technology, and services in developing countries. In: Quisumbing AR, Meinzen-Dick R, Raney TL, Croppenstedt A, Behrman JA, Peterman A (eds) Gender in agriculture. Springer, Dordrecht, pp 145–186

Picchioni F, Zanello G, Srinivasan CS, Wyatt AJ, Webb P (2020) Gender, time-use, and energy expenditures in rural communities in India and Nepal. World Dev 136(December):105137

Pradhan R, Meinzen-Dick R, Theis S (2019) Property rights, intersectionality, and women’s empowerment in Nepal. J Rural Stud 70(August):26–35

Quisumbing A, Kumar N, Behrman J (2018) Do shocks affect men’s and women’s assets differently? Evidence from Bangladesh and Uganda. Dev Policy Rev 36(1):3–34

Quisumbing AR, Sproule K, Martinez EM, Malapit H (2021) Do tradeoffs among dimensions of women’s empowerment and nutrition outcomes exist? Evidence from six countries in Africa and Asia. Food Policy 100(April):102001

Ragasa C, Berhane G, Tadesse F, Taffesse AS (2013) Gender differences in access to extension services and agricultural productivity. J Agric Educ Ext 19(5):437–468

Ragasa C, Aberman N, Alvarez Mingote C (2019) Does providing agricultural and nutrition information to both men and women improve household food security? Evidence from Malawi. Glob Food Sec 20(March):45–59

Ragasa C, Malapit H, Rubin D, Myers E, Pereira A, Martinez E, Heckert J, Seymour G, Mzungu D, Kalagho K, Kazembe C, Thunde J, Mswelo G (2021) ‘It takes two’: women’s empowerment in agricultural value chains in Malawi, IFPRI discussion paper 02006. International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington, DC

Raghunathan K, Kannan S, Quisumbing AR (2019) Can women’s self-help groups improve access to information, decision-making, and agricultural practices? The Indian case. Agric Econ 50(5):567–580

Raghunathan K, Headey D, Herforth A (2021) Affordability of nutritious diets in rural India. Food Policy 99(February):101982

Ragsdale K, Read-Wahidi MR, Wei T, Martey E, Goldsmith P (2018) Using the WEAI+ to explore gender equity and agricultural empowerment: baseline evidence among men and women smallholder farmers in Ghana’s northern region. J Rural Stud 64(November):123–134

Rakib M, Matz J (2014) The impact of shocks on gender-differentiated asset dynamics in Bangladesh. J Dev Stud 52(3):377–395

Rakotomanana H, Hildebrand D, Gates GE, Thomas DG, Fawbush F, Stoecker BJ (2020) Maternal knowledge, attitudes, and practices of complementary feeding and child undernutrition in the Vakinankaratra Region of Madagascar: a mixed-methods study. Curr Dev Nutr 4(11):nzaa162

Rao N, Gazdar H, Chanchani D, Ibrahim M (2019) Women’s agricultural work and nutrition in South Asia: from pathways to a cross-disciplinary, grounded analytical framework. Food Policy 82(January):50–62

Reinbott A, Jordan I (2016) Determinants of child malnutrition and infant and Young child feeding approaches in Cambodia. World Rev Nutr Diet 115:61–67

Reinbott A, Schelling A, Kuchenbecker J, Jeremias T, Russell I, Kevanna O, Krawinkel MB, Jordan I (2016) Nutrition education linked to agricultural interventions improved child dietary diversity in rural Cambodia. Br J Nutr 116(8):1457–1468

Rockström J, Williams J, Daily G, Noble A, Matthews N, Gordon L, Wetterstrand H, DeClerck F, Shah M, Steduto P, de Fraiture C, Hatibu N, Unver O, Bird J, Sibanda L, Smith J (2017) Sustainable intensification of agriculture for human prosperity and global sustainability. Ambio 46(1):4–17

Rowlands J (1998) Questioning empowerment: working with women in Honduras. Oxfam, Oxford

Ruel M, Quisumbing A, Balagamwala M (2018) Nutrition-sensitive agriculture: what have we learned so far? Glob Food Sec 17(June):128–153

Shroff MR, Griffiths PL, Suchindran C, Nagalla B, Vazir S, Bentley ME (2011) Does maternal autonomy influence feeding practices and infant growth in rural India? Soc Sci Med 73(3):447–455

Sibhatu KT, Krishna VV, Qaim M (2015) Production diversity and dietary diversity in smallholder farm households. Proc Natl Acad Sci 112(34):10657–10662

Sraboni E, Quisumbing A (2018) Women’s empowerment in agriculture and dietary quality across the life course: evidence from Bangladesh. Food Policy 81(December):21–36

Tall A, Kristjanson PM, Chaudhury M, McKune S, Zougmoré RB (2014) Who gets the information? Gender, power and equity considerations in the design of climate services for farmers, CCAFS working paper 89. CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security, Copenhagen

Tambo JA, Abdoulaye T (2012) Climate change and agricultural technology adoption: the case of drought tolerant maize in rural Nigeria. Mitig Adapt Strateg Glob Chang 17(3):277–292

Teeken B, Olaosebikan O, Haleegoah J, Oladejo E, Madu T, Bello A, Parkes E, Egesi C, Kulakow P, Kirscht H, Tufan HA (2018) Cassava trait preferences of men and women farmers in Nigeria: implications for breeding. Econ Bot 72(3):263–277

Theis S, Bryan E, Ringler C (2019) Addressing gender and social dynamics to strengthen resilience for all. In: Quisumbing AR, Meinzen-Dick RS, Njuki J (eds) 2019 annual trends and outlook report: gender equality in rural Africa: from commitments to outcomes. International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington, DC, pp 126–139

Theriault V, Smale M, Haider H (2017) How does gender affect sustainable intensification of cereal production in the west African Sahel? Evidence from Burkina Faso. World Dev 92(April):177–191

Tilman D, Balzer C, Hill J, Befort BL (2011) Global food demand and the sustainable intensification of agriculture. Proc Natl Acad Sci 108(50):20260–20264

Törnqvist A, Schmitz C (2009) Women’s economic empowerment: Scope for Sida’s engagement. Sida

Tufan HA, Grando S, Meola C (eds) (2018) State of the knowledge for gender in breeding: case studies for practitioners, Working paper 3. CGIAR Gender and Breeding Initiative, Lima

Twyman J, Green M, Bernier Q, Kristjanson P, Russo S, Tall A, Ampaire E, Nyasimi M, Mango J, McKune S, Mwongera C, Ndourba Y (2014) Adaptation actions in Africa: evidence that gender matters, Working paper 83. CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security, Copenhagen

Uduji JI, Okolo-Obasi EN, Asongu SA (2019) Corporate social responsibility and the role of rural women in sustainable agricultural development in sub-Saharan Africa: evidence from the Niger Delta in Nigeria. Sustain Dev 27(4):692–703

Van den Bold M, Bliznashka L, Ramani G, Olney D, Quisumbing A, Pedehombga A, Ouedraogo M (2021) Nutrition-sensitive agriculture programme impacts on time use and associations with nutrition outcomes. Matern Child Nutr 17(2):e13104

Vibert E (2016) Gender, resilience and resistance: South Africa’s Hleketani community garden. J Contemp Afr Stud 34(2):252–267

Wemakor A, Iddrisu H (2018) Maternal depression does not affect complementary feeding indicators or stunting status of Young children (6–23 months) in northern Ghana. BMC Res Notes 11(1):408

Wemakor A, Mensah KA (2016) Association between maternal depression and child stunting in northern Ghana: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 16(1):869

Wiig H (2013) Joint titling in rural Peru: impact on Women’s participation in household decision-making. World Dev 52(December):104–119

Wolf K, Frese M (2018) Why husbands matter: review of spousal influence on women entrepreneurship in sub-Saharan Africa. Afr J Manag 4(January):1–32

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Annex: Key Terms and Definitionsa

Annex: Key Terms and Definitionsa

Term | Definition | Source |

|---|---|---|

Women’s empowerment | One’s ability to make and act upon strategic and meaningful choices and decisions related to one’s life. | Kabeer (1999) |

Power within | One’s subjectivity, consciousness, and sense of self-worth, self-awareness, self-knowledge and aspirations | Rowlands (1998) |

Power to | One’s access to and ability to use important resources (material, human, social) to employ greater control over key aspects of one’s life and realize one’s own aspirations | |

Power with | Collaborative and collective power with others that occurs through mutual support, collaboration, and collective action that recognizes and respects differences | |

Women’s economic empowerment | “The process which increases women’s real power over economic decisions that influence their lives and priorities in society. Women’s economic empowerment can be achieved through equal access to and control over critical economic resources and opportunities, and the elimination of structural gender inequalities in the labor market including a better sharing of unpaid care work” | Törnqvist and Schmitz (2009, p. 9) |

Gender-transformative | Approaches that “go beyond the ‘symptoms’ of gender inequality to address the social norms, attitudes, behaviors, and social systems that underlie them” | Hillenbrand et al. (2015, p. 5) |

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Njuki, J., Eissler, S., Malapit, H., Meinzen-Dick, R., Bryan, E., Quisumbing, A. (2023). A Review of Evidence on Gender Equality, Women’s Empowerment, and Food Systems. In: von Braun, J., Afsana, K., Fresco, L.O., Hassan, M.H.A. (eds) Science and Innovations for Food Systems Transformation. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-15703-5_9

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-15703-5_9

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-15702-8

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-15703-5

eBook Packages: Biomedical and Life SciencesBiomedical and Life Sciences (R0)