Abstract

Background

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a global public health concern that is fueled by the overuse of antimicrobial agents. Low- and middle-income countries, including those in Africa,. Point prevalence surveys (PPS) have been recognized as valuable tools for assessing antimicrobial utilization and guiding quality improvement initiatives. This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to evaluate the prescription rates, indications, and quality of antimicrobial use in African health facilities.

Methods

A comprehensive search was conducted in multiple databases, including PubMed, Scopus, Embase, Hinari (Research4Life) and Google Scholar. Studies reporting the point prevalence of antimicrobial prescription or use in healthcare settings using validated PPS tools were included. The quality of the studies was assessed using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical appraisal checklist. A random-effects meta-analysis was conducted to combine the estimates. Heterogeneity was evaluated using Q statistics, I² statistics, meta-regression, and sensitivity analysis. Publication bias was assessed using a funnel plot and Egger’s regression test, with a p-value of < 0.05 indicating the presence of bias.

Results

Out of 1790 potential studies identified, 32 articles were included in the meta-analysis. The pooled prescription rate in acute care hospitals was 60%, with significant heterogeneity (I2 = 99%, p < 0.001). Therapeutic prescriptions constituted 62% of all the prescribed antimicrobials. Prescription quality varied: documentation of reasons in notes was 64%, targeted therapy was 10%, and parenteral prescriptions were 65%, with guideline compliance at 48%. Hospital-acquired infections comprised 20% of all prescriptions. Subgroup analyses revealed regional disparities in antimicrobial prescription prevalence, with Western Africa showing a prevalence of 65% and 44% in Southern Africa. Publication bias adjustment estimated the prescription rate at 54.8%, with sensitivity analysis confirming minor variances among studies.

Conclusion

This systematic review and meta-analysis provide valuable insights into antimicrobial utilization in African health facilities. The findings highlight the need for improved antimicrobial stewardship and infection control programs to address the high prevalence of irrational antimicrobial prescribing. The study emphasizes the importance of conducting regular surveillance through PPS to gather reliable data on antimicrobial usage, inform policy development, and monitor the effectiveness of interventions aimed at mitigating AMR.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

An antimicrobial agent, as defined, is a natural or synthetic substance that kills or inhibits the growth of microorganisms. The antimicrobial era significantly improved global infectious disease treatment, particularly in developed countries, reducing morbidity and mortality [1, 2]. However, antimicrobial resistance (AMR), fueled by antimicrobial overuse worldwide, remains a critical public health concern, resulting in severe infections, prolonged hospital stays, and increased mortality rates [3,4,5].

The rising rates of AMR globally have led to the utilization of more costly broad-spectrum antimicrobial previously reserved for specific conditions [3], contributing to increased morbidity, mortality, and healthcare expenses [6,7,8]. Recognizing the escalating concerns surrounding AMR, the World Health Organization (WHO) introduced a Global Action Plan (GAP) during the 68th World Health Assembly in May 2015 [9]. Additionally, a declaration on AMR by Heads of State during the United Nations (UN) General Assembly on September 21, 2016, reinforced the GAP’s objectives. One of the primary aims of the GAP is to devise strategies ensuring the appropriate use of antimicrobials, thereby mitigating inappropriate antimicrobial use and associated AMR rates in the future [10].

A crucial strategy to achieve these objectives involves conducting regular surveillance of antimicrobial use through point prevalence surveys (PPS) [11]. Consequently, numerous PPS have been carried out worldwide to enhance future antimicrobial utilization. PPS serves as a vital tool for gathering precise data on current antimicrobial usage, facilitating improvements in antimicrobial use within hospitals and consequently reducing resistance [3]. Moreover, it enables the monitoring of antimicrobial stewardship (AMS) and infection control programs. Point prevalence, defined as the ratio of individuals with a condition to the total population within a specific time interval, underscores the significance of PPS in healthcare settings [12]. PPS of antimicrobial use are typically undertaken to assess current in-patient antimicrobial utilization for treating infections, with the findings driving relevant quality improvement initiatives within hospitals [13,14,15,16,17].

The rate of inappropriate empirical antimicrobial prescribing for severe infections in hospitals is currently estimated to range from 14.1 to 78.9% of inpatient treatments [18]. Low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), including those in Africa, bear disproportionate consequences due to inadequate funding, hindering access to expensive second or third-line treatment options [3, 19]. Studies have shown a drastic over 65% increase in antimicrobial consumption between 2000 and 2015, driven by excessive antimicrobial prescriptions in LMICs [20].

While numerous PPS studies have delved into varying prevalence of antimicrobial use and offered insights into current antimicrobial prescribing practices, there remains a dearth of synthesized evidence on this subject in Africa [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. Furthermore, this systematic review and meta-analysis provides additional insights specific to the region under study. It aims to consolidate available evidence consistently utilizing validated PPS tools to evaluate the proportion of antimicrobial prescription, indications, and quality of use in African health facilities.

Methods

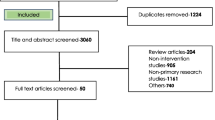

Reporting and protocol registration

For screening eligible studies, this review utilized the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses [PRISMA] checklist for reporting a systematic review or meta-analysis protocol [29]. The protocol for this systematic review and meta-analysis can be found at Prospero with registration number: CRD42024513972.

Databases and search strategy

The search encompassed studies published prior to the search date on the point prevalence of antibiotic and/or antimicrobial use in Africa. The following databases and sources were searched: PubMed, Hinari (Research4Life), Scopus, Embase, and Google Scholar. Additionally, the proceedings of professional associations and university repositories were scrutinized. A direct Google search was conducted, and bibliographies of identified studies were reviewed to include any relevant studies inadvertently omitted during electronic database searches. Some of the terms employed in the search include but are not limited to the following: prevalence, point prevalence, antibiotic, antimicrobial, prescription use. The Boolean operators “OR” and “AND” were used as appropriate (Supplementary file 1). The management of references and removal of duplicates were handled using Endnote 20 software [30]. The search was conducted from February 11 to 26, 2024, and all articles available online during the data collection period were considered.

Eligibility criteria

The eligibility criteria for inclusion of studies include cross-sectional studies regardless of publication period published or retrievable in English language, and studies conducted in Africa. The study must report point prevalence of antimicrobial/antibiotic prescription or use in health care settings using point prevalence survey tools. Additionally, restrictions applied solely to antimicrobials used for human patients. Studies conducted on home-based hospital care (HBHC) (where patients receive medical treatment and monitoring in their own homes), long-term care facilities (LTCFs), and nursing homes were excluded. In addition, studies involving antimicrobial consumption at outpatient clinics and pharmacies were excluded. The studies that did not follow the structured standardized survey methodology employed by the European Centre of Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), Global PPS, and WHO PPS [31,32,33] or related research methods were also subsequently excluded. Moreover, studies not published in the English language, reviews, editorials, commentaries, case reports, and case series and qualitative were excluded.

Data extraction

Three authors following a predefined data extraction format derived from the Global-PPS of antimicrobial consumption and resistance [14] carried out data extraction idependently. In instances of discrepancies, a repeated procedure was employed to ensure accuracy and consistency. These authors performed the consolidation and summarization of the final set of articles that met our inclusion criteria. The fields included in the extraction form were first author´s name, year the study was conducted, country of study, the protocol used, UN-Africa zone, number of facilities involved, study population, sample size, total patients with antimicrobials, total number of antimicrobials prescribed, indications (treatment and prophylaxis), antimicrobial use quality indicators (guideline compliance, reasons in note, stop/review date, targeted therapy and duration of surgical prophylaxis) antimicrobials with the parenteral route and source of infections as hospital acquired and community acquired. Table 1 provides the general characteristics of the included studies along with their respective information.

Selection and quality appraisal

We utilized EndNote version 20.5 Reference Manager software [30], a tool designed for managing and organizing references and citations, to eliminate duplicate studies. The titles and abstracts were independently screened by two authors (MY and NA) to determine which articles should undergo a full-text review. The full text of the remaining articles was then obtained, and two investigators, AG and MH, independently assessed them for eligibility. The quality of the studies was evaluated using the JBI critical appraisal checklist [34]. This quality assessment tool contained nine questions which explored the adequacy of the sample frame, sampling of study participants, adequacy of sample size, description of study subjects and setting, data analysis conducted with sufficient coverage of the identified sample, valid methods used for the identification of the condition, response rate and appropriate statistical analysis amongst others. Final decisions on inclusion or exclusion were made by independent authors, and in cases of discrepancies, a third author was consulted to reach a resolution. For each variable, the scoring options were Yes, No, Unclear, and Not Applicable. The adequacy of sample size was marked as Not Applicable for all studies in this review, as the PPS tool does not require sample size calculation. None of the included studies suffered from bias.

Data analysis

To estimate the prevalence of antimicrobial prescriptions in acute care facilities across Africa, we utilized a weighted inverse variance random-effects model. Heterogeneity among studies was assessed using a forest plot, meta-regression, and the I² statistic, with values of 25%, 50%, and 75% denoting low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively. The Q test was employed to quantify the degree of heterogeneity, where a p-value less than 0.05 indicated significant heterogeneity. A Galbraith plot was employed to evaluate the individual contributions of each study to the overall heterogeneity. Subgroup analysis based on the study population, region where the studies were conducted. To assess publication bias, we employed a funnel plot and Egger’s regression test, where a p-value less than 0.05 suggested significant publication bias. Additionally, trim and fill analysis was applied to further evaluate the presence of publication bias in details. A sensitivity analysis was conducted to ensure the stability of the summary estimate. The meta-analysis was performed using STATA version 17 statistical software.

Outcome of interest

The outcomes of interest include the prevalence of antimicrobial prescriptions in acute care hospitals, which is calculated by dividing the number of patients receiving antimicrobial treatment by the total number of admitted patients. Infections are categorized as healthcare-associated or community-acquired based on the onset of symptoms. Quality indicators encompass several aspects: the use of parenteral routes (such as intravenous therapy), targeted therapy based on culture results, thorough documentation of reasons for antimicrobial use and stop/review dates, and adherence to established treatment guidelines.

Result

Characteristics of included studies

A total of 1795 potential studies were sourced from multiple channels, including 366 articles from PubMed, 241 from Hinari (research4life), 545 from EMBASE, 573 from Scopus, and 70 from Google Scholar (Supplementary file 1). Figure 1 presents the search outcomes and details the reasons for exclusion during the study selection phase.

After a thorough evaluation and assessment, 102 articles were initially considered for retrieval. Of these, 101 articles were successfully retrieved (one study could not be reviewed because the full text was not accessible to us) and assessed for eligibility, with 30 articles meeting the inclusion criteria. Additionally, 2 more articles were identified through reference tracing, bringing the total to 32 articles. These articles were included in the meta-analysis, which focused on assessing the prevalence, indications, and quality of antimicrobial prescriptions across Africa. All selected studies adhered to the G-PPS protocol or related standards. Geographically, the studies spanned various African regions, with approximately half conducted in Western Africa [35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49], twelve in Eastern Africa [22, 26, 50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59], four in Southern Africa [21, 25, 27, 60], and one in Northern Africa [61]. This comprehensive analysis involved 182 healthcare facilities and 37,364 participants, with 20,598 individuals receiving at least one antimicrobial during the study period. A total of 36,378 antimicrobials, along with their daily-defined doses (DDD), were prescribed for admitted patients across these facilities. For a detailed overview of the included studies and their characteristics, please refer to Table 1.

Meta-analysis

Proportion of antimicrobial prescription

We discovered that the aggregated estimate of antimicrobial prescription proportions in acute care hospitals across Africa stands at 60% (95% CI: 55, 65). The heterogeneity, as measured by I2, was found to be 99%, and a p-value < 0.001(Fig. 2).

Indications for antimicrobial prescription

We categorized the reasons for antimicrobial prescriptions into therapeutic and prophylactic indications. Further classification of prophylaxis included surgical and medical prophylaxis. The analysis revealed that the prescribing estimate for therapeutic purposes is 62% (95% CI: 56–69). Additionally, antimicrobial prescriptions for medical prophylaxis were identified at 14% (95% CI: 11–17), while surgical prophylaxis accounted for 27% (95% CI: 22–32) (Table 2 and Supplementary file 2).

Assessment of quality of antimicrobial prescription

We evaluated the quality of antimicrobial prescriptions based on various criteria. These criteria included the documentation of reasons in notes, the presence of stop/review dates, and compliance to guidelines, the practice of targeted therapy, and the proportion of parenteral antimicrobials. Our findings indicate a range of quality across these parameters. The prevalence of prescribing for targeted therapy was observed at 10% (95% CI: 8–13), while documentation of reasons in notes demonstrated a higher proportion at 64% (95% CI: 55–73) as illustrated in Table 2. The coverage of parenteral antimicrobial prescriptions in our study was found to be 65% (95% CI: 50–80). Furthermore, in our meta-analysis, we identified that among patients receiving surgical prophylaxis, a substantial 87% (95% CI: 83–91) were prescribed an extended duration of therapy beyond the recommended period (Table 2).

Source of infections

Within the context of this meta-analysis, our examination of antimicrobial prescriptions revealed distinct sources of infections. Hospital-acquired infections (HAIs) accounted for 20% (95% CI: 14–26) of all prescriptions, while the majority, comprising 80% (95% CI: 74–86), were associated with community-acquired infections (CAIs) (Table 2).

Heterogeneity analysis

The studies incorporated into the analysis exhibited substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 99%%; p value < 0.001), and the application of a weighted inverse variance random-effects model did not adequately address this variability. To further explore and understand the heterogeneity, we employed a forest plot (Fig. 2) for subjective assessment and conducted subgroup analyses along with univariate meta-regression utilizing number of health facilities involved, sample size, and publication years as variables (Fig. 3 and Supplementary file 2).

A Galbraith plot was employed to evaluate the individual contributions of each study to the overall heterogeneity in our analysis. The symmetrical pattern observed in the plot (Supplementary file 2), suggests that each study included in the meta-analysis contributes in a balanced and similar manner to the overall heterogeneity.

Subgroup analysis

In our comprehensive subgroup analysis, we meticulously examined the nuanced variations in antimicrobial prescription proportion by categorizing the data based on distinct factors. Firstly, when stratifying the analysis by African regions, noteworthy differences emerged. Western Africa exhibited the highest prevalence of antimicrobial prescriptions at a proportion of 66% (95% CI: 60, 71), as illustrated in Fig. 4, while Southern Africa health facilities showed a comparatively lower proportion of 44% (95% CI: 27, 60), highlighting regional disparities. Furthermore, our exploration extended to subgroup analysis based on study populations, namely adults, pediatrics, and mixed cohorts. The analysis revealed a lower proportion in adults, with a prevalence of 39% (95% CI: 28, 49). Conversely, comparable antimicrobial prescription proportion were identified in mixed and pediatrics subjects, standing at 60% (95% CI: 55, 65) and 67% (95% CI: 54, 79), respectively, as depicted in Fig. 5.

Publication bias

We evaluated publication bias by subjectively examining the funnel plot (Fig. 6) and conducting Egger’s regression test, yielding a p-value of 0.344, which did not provide evidence for the presence of publication bias. However, the subsequent trim and fill analysis, incorporating five additional studies, suggested the potential existence of missed small studies. After this adjustment, the estimated prevalence of antimicrobial prescription proportion was recalibrated to 54.8% (95% CI: 49.7, 59.9) (Supplementary file 2).

Sensitivity analysis

A sensitivity analysis was undertaken to employ a random effects model to evaluate the influence of individual included studies on the collective antimicrobial prescription rate in African health facilities. Each of the excluded studies revealed minor variances in antimicrobial prescription rates within these facilities.

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis stands as one of the limited studies delving into the comprehensive landscape of antimicrobial usage within the healthcare settings of Africa. It scrutinizes prescription rates, indications, and the quality of antimicrobial use. The findings reveal a concerning trend of elevated antimicrobial prescription rates in acute care hospitals and frequent antimicrobial usage for hospital-acquired infections, often with suboptimal documentation and lower level of guideline compliance. Moreover, the prevalence of evidence-based antimicrobial therapy is notably lower in African health facilities.

The pooled estimate prevalence of antimicrobial prescription within hospital settings across Africa stood at 60%. This finding is consistent with a recent systematic review in East Africa, which reported a 57% prevalence of antimicrobial use among hospitalized patients across 26 studies [62]. Moreover, it corresponds to a narrative review compiled from 33 PPS studies, indicating over 50% antimicrobial utilization among inpatients [63]. In line with our results, another systematic review encompassing 27 low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) from 48 studies revealed a 52% proportion of antimicrobial prescribing [64]. Similarly, it mirrors findings from a study conducted in India, which reported a 57.4% prescription rate [65]. Although there is a slight difference in terms of the exact numerical figure, all the systematic reviews and meta-analyses done in Africa share a commonality in that monolithic antimicrobial prescription rates are incurred which substantially deviates from the WHO standard recommendation (≤ 20%) [66]. Notably, our findings contrast with those from systematic reviews and meta-analyses conducted in Europe and the USA, as well as a multicenter study in Canada, which reported respective proportions of antimicrobial use in inpatient settings as 30.5%, 49.9%, and 34% [67,68,69]. Several factors could explain these disparities. One possible reason is the type of patients admitted to healthcare facilities in Africa, where there is often a higher burden of infectious diseases. This increased burden may lead to more frequent empirical prescribing of antimicrobials, especially in the absence of robust diagnostic facilities. Additionally, healthcare systems in many African countries may face challenges such as limited resources, inadequate infection control measures, and a lack of adherence to clinical guidelines, all of which can contribute to higher rates of antimicrobial use. These factors, combined with the variability in healthcare infrastructure and disease prevalence, likely account for the observed differences in antimicrobial prescribing patterns between African and high-income countries.

Our meta-analysis estimated that the proportion of antimicrobial prescribing for therapeutic and prophylactic purposes demonstrated 62% and 38%, respectively. The result of this study unveiled that approximately 80% of the antimicrobial prescriptions were indicated to community-acquired infections (CAIs) while 20% accounted for hospital-acquired infections (HAIs). Amongst these prophylactic prescriptions, 13% were attributed to medical prophylaxis while 25% were ascribed to surgical prophylaxis. Alas, the use of antimicrobials for healthcare-associated infections in this study is higher than recommended by the WHO [66]. A substantial proportion of inpatients in Africa are prescribed antimicrobials for the intent of treating CAIs. In support of our finding, a recent systematic review [70] reported that the most common indications for antimicrobial use was CAIs (ranging from 27.7 to 61.0%) then followed by surgical prophylaxis (14.6–45.3%), and medical prophylaxis (0.5–29.1%). The fact that CAIs are common reasons for antimicrobial use in Africa is in keeping with the finding in Europe [68], the USA [67], and the global PPS of antimicrobial use [14]. This mutual outcome underscores the necessity of encouraging infection control and prevention measures within the community to alleviate the impact of infections acquired outside of healthcare settings, ultimately leading to a decrease in antimicrobial usage.

The prescribing and quality indicators deployed to appraise the quality of antimicrobial prescribing across Africa variegated across the studies. According to the specifically delineated criterion set to examine the overall quality of antimicrobial prescription, substantial proportion accounted to parenteral antimicrobial prescribing (65%) and documentation of reasons in notes (64%) while modest proportions were observed to targeted therapy prescribing (10%). This finding is in keeping with a nascent systematic review [70] that indicated higher rates of documentation of reasons in notes (ranged from 37.3 to 100%), documentation of dates for stop/review (ranged from 19.6 to 100%), and parenteral prescribing (ranged from 54.0 to 98.6%). Nevertheless, this finding is incongruent to another review done exclusively on sub-Saharan Africa that revealed switching from intravenous (IV) to oral as well as documentation of start and stop dates among the least reported quality indicators [71]. The parenteral prescribing rate discovered in our study is quite lower as compared to a systematic review done in East African states [62] that reported a 28% patient encounter with injectable antimicrobials. Interestingly, out of the total patients who received surgical prophylaxis, interestingly, 87% of the patients who received surgical prophylaxis were prescribed therapy beyond the recommended duration. Similar observations were noted in previous studies done in both Africa [62, 63, 70] and outside Africa [67, 68] indicating immense prevalence of prolonged (more than 24 h) surgical antimicrobial prophylaxis. Inordinate utilization of surgical antimicrobial prophylaxis exacerbates the emergence and spread of AMR.

The sub-group analysis done based on specific region types in Africa unveiled that Western Africa exhibited the highest prevalence of antimicrobial prescriptions at a rate of 65% while the Southern Africa demonstrated the lowest proportion of prescriptions at a rate of 44%. This worrying finding is consistent with a recent systematic review and meta-analysis [70] that revealed more prominent prevalence of antimicrobial use in West Africa (ranged from 51.4 to 83.5%), followed by North Africa (79.1%), East Africa (ranged from 27.6 to 73.7%), and South Africa (ranged from 33.6 to 49.7%). The lower utilization rates observed in South Africa is suggestive of the effectual implementation of Antimicrobial Resistance National Strategy Framework along with veritable availability of microbiology laboratories and regular monitoring of hospitals’ genuine performance. Perhaps, the encouraging experience of South Africa should be apportioned to the other regions of the continent as well to improve future antimicrobial prescribing and reduce AMR across Africa.

According to the current study, the subgroup analysis based on study populations revealed that massive antimicrobial prescription rates (67%) were reported in the pediatric population while lower rates (39%) were detected in the adult population. Possibly, this could be attributed to higher prevalence of infectious diseases in pediatric population. Additionally, this finding designates the huge role of prioritizing inpatient wards involving pediatric population to pragmatically implement AMS program.

The substantial heterogeneity observed in our analysis, as indicated by an I2 of 99% and a p-value < 0.001, persisted despite the application of a weighted inverse variance random-effects model, suggesting inherent variability among the included studies. To further explore this heterogeneity, we employed forest plots and conducted subgroup analyses and meta-regression, revealing nuanced variations influenced by factors such as the number of health facilities involved, sample size, and publication years. Additionally, our Galbraith plot suggested that each study contributed to the overall heterogeneity in a balanced manner. Regarding publication bias assessment, while Egger’s regression test did not indicate significant bias, trim and fill analysis suggested potential missed small studies, prompting an adjustment to the estimated prevalence of antimicrobial prescription rate. Our sensitivity analysis using a random effects model underscored the minor variances in prescription rates among individual studies, further emphasizing the need for careful consideration of study characteristics in interpreting the collective antimicrobial prescription rates observed in African health facilities.

Conclusion

The notable prevalence of antimicrobial use among hospitalized patients in Africa underscores the urgent need for antimicrobial stewardship programs to promote the judicious use of these medications. The variations in point prevalence across different regions, particularly the higher rates observed in West Africa, further emphasize the necessity for stringent implementation of infection control and prevention measures within communities. Reducing the burden of infections through improved water, sanitation, hygiene, and vaccination is essential. However, the higher risk of infection in LMICs can also be attributed to socio-economic factors and co-morbidities such as HIV and malnutrition. Addressing these underlying issues is crucial for mitigating inappropriate antimicrobial usage and improving overall health outcomes.

Strengths and limitations of the study

This comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to elucidate the current status of antimicrobial prescription rates, indications, and quality of antimicrobial use in African health facilities. However, several limitations warrant acknowledgment. Primarily, the majority of included studies originated from Western and Eastern Africa, with limited representation from Northern Africa. This regional disparity may compromise the generalizability of findings to the entire continent. Significant heterogeneity among the included studies may impact the overall estimation of the findings. Additionally, the exclusion of non-English language publications might have led to the oversight of relevant articles, potentially impacting the comprehensiveness of the study. Consequently, caution is warranted when extrapolating the results to the broader African context. Despite these limitations, the study offers valuable insights into antimicrobial usage trends in African healthcare settings, contributing to the understanding of antimicrobial stewardship efforts in the region.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Abbreviations

- ECDC:

-

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control

- G-PPS:

-

Global Point Prevalence Survey

- ESAC:

-

European Surveillance of Antimicrobial Consumption

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization AMR: Antimicrobial Resistance

- GAP:

-

Global Action Plan

- UN:

-

United Nations

- AMS:

-

Antimicrobial Stewardship

- LMIC:

-

Low- and middle-income countries

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- HBHC:

-

Home-Based Hospital Care

- LTCFs:

-

Long-Term Care Facilities

- DDD:

-

Daily-Defined Doses

- HAIs:

-

Hospital-Acquired Infections

- CAIs:

-

Community-Acquired Infections

References

Baker RE, Mahmud AS, Miller IF, Rajeev M, Rasambainarivo F, Rice BL, Takahashi S, Tatem AJ, Wagner CE, Wang L-F. Infectious disease in an era of global change. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2022;20(4):193–205.

Di Martino P. Antimicrobial agents and microbial ecology. AIMS Microbiol. 2022;8(1):1.

Bell BG, Schellevis F, Stobberingh E, Goossens H, Pringle M. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of antibiotic consumption on antibiotic resistance. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:1–25.

Godman B, Fadare J, Kibuule D, Irawati L, Mubita M, Ogunleye O, Oluka M, Paramadhas BDA, Costa JO, de Lemos LLP. Initiatives across countries to reduce antibiotic utilisation and resistance patterns: impact and implications. Drug resistance in bacteria, fungi, malaria, and cancer. 2017:539 – 76.

Llor C, Bjerrum L. Antimicrobial resistance: risk associated with antibiotic overuse and initiatives to reduce the problem. Therapeutic Adv drug Saf. 2014;5(6):229–41.

Cassini A, Högberg LD, Plachouras D, Quattrocchi A, Hoxha A, Simonsen GS, Colomb-Cotinat M, Kretzschmar ME, Devleesschauwer B, Cecchini M. Attributable deaths and disability-adjusted life-years caused by infections with antibiotic-resistant bacteria in the EU and the European Economic Area in 2015: a population-level modelling analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019;19(1):56–66.

Founou RC, Founou LL, Essack SY. Clinical and economic impact of antibiotic resistance in developing countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(12):e0189621.

O’neill J. Antimicrobial resistance: tackling a crisis for the health and wealth of nations. Rev Antimicrob Resist. 2014.

Organization WH. Report of the 6th meeting of the WHO advisory group on integrated surveillance of antimicrobial resistance with AGISAR 5-year strategic framework to support implementation of the global action plan on antimicrobial resistance (2015–2019), 10–12 June 2015. Seoul, Republic of Korea: World Health Organization; 2015.

Boucher HW, Bakken JS, Murray BE. The United Nations and the urgent need for coordinated global action in the fight against antimicrobial resistance. American College of Physicians; 2016. pp. 812–3.

Versporten A, Bielicki J, Drapier N, Sharland M, Goossens H, Group AP, Calle GM, Garrahan JP, Clark J, Cooper C. The Worldwide Antibiotic Resistance and Prescribing in European Children (ARPEC) point prevalence survey: developing hospital-quality indicators of antibiotic prescribing for children. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016;71(4):1106–17.

Aldeyab MA, Kearney MP, McElnay JC, Magee FA, Conlon G, Gill D, Davey P, Muller A, Goossens H, Scott MG. A point prevalence survey of antibiotic prescriptions: benchmarking and patterns of use. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;71(2):293–6.

Van Boeckel TP, Gandra S, Ashok A, Caudron Q, Grenfell BT, Levin SA, Laxminarayan R. Global antibiotic consumption 2000 to 2010: an analysis of national pharmaceutical sales data. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14(8):742–50.

Versporten A, Zarb P, Caniaux I, Gros M-F, Drapier N, Miller M, Jarlier V, Nathwani D, Goossens H, Koraqi A. Antimicrobial consumption and resistance in adult hospital inpatients in 53 countries: results of an internet-based global point prevalence survey. Lancet Global Health. 2018;6(6):e619–29.

Xie D-s, Xiang L-l, Li R, Hu Q, Luo Q-q, Xiong W. A multicenter point-prevalence survey of antibiotic use in 13 Chinese hospitals. J Infect Public Health. 2015;8(1):55–61.

Zarb P, Coignard B, Griskeviciene J, Muller A, Vankerckhoven V, Weist K, Goossens MM, Vaerenberg S, Hopkins S, Catry B. The European centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) pilot point prevalence survey of healthcare-associated infections and antimicrobial use. Eurosurveillance. 2012;17(46):20316.

German GJ, Frenette C, Caissy JA, Grant J, Lefebvre MA, Mertz D, Lutes S, McGeer A, Roberts J, Afra K, Valiquette L, Émond Y, Carrier M, Lauzon-Laurin A, Nguyen TT, Al-Bachari H, Kosar J, Peermohamed S, Science M, Landry D, MacLaggan T, Daley P, McDonald G, Ang A, Chang S, Lin YC, Tong B, Malfair S, Leung V, Katz K, Pauwels I, Goossens H, Versporten A, Conly J, Thirion DJG. The 2018 Global Point Prevalence Survey of antimicrobial consumption and resistance in 47 Canadian hospitals: a cross-sectional survey. CMAJ open. 2021;9(4):E1242–51.

Marquet K, Liesenborgs A, Bergs J, Vleugels A, Claes N. Incidence and outcome of inappropriate in-hospital empiric antibiotics for severe infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2015;19:1–12.

Boltena MT, Woldie M, Siraneh Y, Steck V, El-Khatib Z, Morankar S. Adherence to evidence-based implementation of antimicrobial treatment guidelines among prescribers in sub-saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pharm Policy Pract. 2023;16(1):137.

Klein EY, Van Boeckel TP, Martinez EM, Pant S, Gandra S, Levin SA, Goossens H, Laxminarayan R. Global increase and geographic convergence in antibiotic consumption between 2000 and 2015. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2018;115(15):E3463–70.

Anand Paramadhas BD, Tiroyakgosi C, Mpinda-Joseph P, Morokotso M, Matome M, Sinkala F, Gaolebe M, Malone B, Molosiwa E, Shanmugam MG. Point prevalence study of antimicrobial use among hospitals across Botswana; findings and implications. Expert Rev anti-infective Therapy. 2019;17(7):535–46.

Fentie AM, Degefaw Y, Asfaw G, Shewarega W, Woldearegay M, Abebe E, Gebretekle GB. Multicentre point-prevalence survey of antibiotic use and healthcare-associated infections in Ethiopian hospitals. BMJ open. 2022;12(2):e054541.

Kehinde A, Oduyebo O. Point Prevalence Survey of Antimicrobial Prescribing in a Nigerian hospital: findings and implications on Antimicrobial Resistance. West Afr J Med. 2020;37(3):217.

Labi A-K, Obeng-Nkrumah N, Sunkwa-Mills G, Bediako-Bowan A, Akufo C, Bjerrum S, Owusu E, Enweronu-Laryea C, Opintan JA, Kurtzhals JAL. Antibiotic prescribing in paediatric inpatients in Ghana: a multi-centre point prevalence survey. BMC Pediatr. 2018;18:1–9.

Mthombeni TC, Burger JR, Lubbe MS, Julyan M. Antibiotic prescribing to inpatients in Limpopo, South Africa: a multicentre point-prevalence survey. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2023;12(1):103.

Okoth C, Opanga S, Okalebo F, Oluka M, Baker Kurdi A, Godman B. Point prevalence survey of antibiotic use and resistance at a referral hospital in Kenya: findings and implications. Hosp Pract. 2018;46(3):128–36.

Skosana P, Schellack N, Godman B, Kurdi A, Bennie M, Kruger D, Meyer J. A point prevalence survey of antimicrobial utilisation patterns and quality indices amongst hospitals in South Africa; findings and implications. Expert Rev anti-infective Therapy. 2021;19(10):1353–66.

Skosana P, Schellack N, Godman B, Kurdi A, Bennie M, Kruger D, Meyer J, editors. Multicentre point prevalence survey regarding antimicrobial use among community healthcare centres across South Africa. 2nd Annual African Regional Interest Group Meeting; 2022.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):W–65.

Gotschall T. EndNote 20 desktop version. J Med Libr Association: JMLA. 2021;109(3):520.

Chen H, Somani J, Wu J, Foo G, Chung G. The Global Point Prevalence Survey of Antimicrobial Consumption and Resistance (GLOBAL-PPS): comparison of results over the years2015–2019. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;101:109.

Porto AM, Goossens H, Versporten A, Costa SF, Group BG-PW. Global point prevalence survey of antimicrobial consumption in Brazilian hospitals. J Hosp Infect. 2020;104(2):165–71.

Prevention, ECfD. Control. Point prevalence survey of healthcare-associated infections and antimicrobial use in European acute care hospitals. Stockholm. 2013.

Parums DV. Review articles, systematic reviews, meta-analysis, and the updated preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines. Med Sci Monitor: Int Med J Experimental Clin Res. 2021;27:e934475–1.

Aboderin AO, Adeyemo AT, Olayinka AA, Oginni AS, Adeyemo AT, Oni AA, Olabisi OF, Fayomi OD, Anuforo AC, Egwuenu A, Hamzat O, Fuller W. Antimicrobial use among hospitalized patients: a multi-center, point prevalence survey across public healthcare facilities, Osun State, Nigeria. Germs (Bucureşti). 2021;11(4):523–35.

Abubakar U. Antibiotic use among hospitalized patients in northern Nigeria: a multicenter point-prevalence survey. BMC Infect Dis. 2020;20(1):86.

Afriyie DK, Sefah IA, Sneddon J, Malcolm W, McKinney R, Cooper L, Kurdi A, Godman B, Seaton RA. Antimicrobial point prevalence surveys in two Ghanaian hospitals: opportunities for antimicrobial stewardship. JAC-antimicrobial Resist. 2020;2(1):dlaa001–dlaa.

Amponsah OKO, Buabeng KO, Owusu-Ofori A, Ayisi-Boateng NK, Hämeen-Anttila K, Enlund H. Point prevalence survey of antibiotic consumption across three hospitals in Ghana. JAC-antimicrobial Resist. 2021;3(1):dlab008–dlab.

Ankrah D, Owusu H, Aggor A, Osei A, Ampomah A, Harrison M, Nelson F, Aboagye GO, Ekpale P, Laryea J, Selby J, Amoah S, Lartey L, Addison O, Bruce E, Mahungu J, Mirfenderesky M. Point Prevalence Survey of Antimicrobial utilization in Ghana’s Premier Hospital: implications for Antimicrobial Stewardship. Antibiot (Basel). 2021;10(12):1528.

Awopeju ATO, Robinson NI, Ossai-Chidi LN, Jonah AA, Alex-Wele MA, Oboro IL, Okoli CD, Duru CC, Ugwu R, Yago-Ide LE, Paul NI, Wariso KT, Obunge OK. Point Prevalence Survey of Antimicrobial prescription and indicators in a Tertiary Healthcare Center in Southern Nigeria. South Asian J Res Microbiol. 2023;15(3):1–9.

Briggs DC, Oboro IL, Bob-Manuel M, Amadi SC, Enyinnaya SO, Lawson SD, Dan-Jumbo AI. Antibiotic prescription patterns in paediatric wards of Rivers State university teaching hospital, southern Nigeria: a point prevalence survey. Nigerian Health J. 2023;23(3):837–43.

Dodoo CC, Orman E, Alalbila T, Mensah A, Jato J, Mfoafo KA, Folitse I, Hutton-Nyameaye A, Okon Ben I, Mensah-Kane P, Sarkodie E, Kpokiri E, Ladva M, Awadzi B, Jani Y. Antimicrobial prescription pattern in Ho Teaching Hospital, Ghana: Seasonal determination using a point prevalence survey. Antibiot (Basel). 2021;10(2):199.

Fowotade A, Fasuyi T, Aigbovo O, Versporten A, Adekanmbi O, Akinyemi O, Goossens H, Kehinde A, Oduyebo O. Point Prevalence Survey of Antimicrobial Prescribing in a Nigerian hospital: findings and implications on Antimicrobial Resistance. West Afr J Med. 2020;37(3):216–20.

Labi A-K, Obeng-Nkrumah N, Sunkwa-Mills G, Bediako-Bowan A, Akufo C, Bjerrum S, Owusu E, Enweronu-Laryea C, Opintan JA, Kurtzhals JAL. Antibiotic prescribing in paediatric inpatients in Ghana: a multi-centre point prevalence survey. BMC Pediatr. 2018;18(1):1–9.

Labi AK, Obeng-Nkrumah N, Dayie N, Egyir B, Sampane-Donkor E, Newman MJ, Opintan JA. Antimicrobial use in hospitalized patients: a multicentre point prevalence survey across seven hospitals in Ghana. JAC Antimicrob Resist. 2021;3(3):dlab087.

Labi AK, Obeng-Nkrumah N, Owusu E, Bjerrum S, Bediako-Bowan A, Sunkwa-Mills G, Akufo C, Fenny AP, Opintan JA, Enweronu-Laryea C, Debrah S, Damale N, Bannerman C, Newman MJ. Multi-centre point-prevalence survey of hospital-acquired infections in Ghana. J Hosp Infect. 2019;101(1):60–8.

Ogunleye OO, Oyawole MR, Odunuga PT, Kalejaye F, Yinka-Ogunleye AF, Olalekan A, Ogundele SO, Ebruke BE, Kalada Richard A, Anand Paramadhas BD. A multicentre point prevalence study of antibiotics utilization in hospitalized patients in an urban secondary and a tertiary healthcare facilities in Nigeria: findings and implications. Expert Rev anti-infective Therapy. 2022;20(2):297–306.

Umeokonkwo C, Oduyebo O, Fadeyi A, Versporten A, Ola-Bello O, Fowotade A, Elikwu C, Pauwels I, Kehinde A, Ekuma A. Point prevalence survey of antimicrobial consumption and resistance: 2015–2018 longitudinal survey results from Nigeria. Afr J Clin Experimental Microbiol. 2021;22(2):252–9.

Umeokonkwo CD, Madubueze UC, Onah CK, Okedo-Alex IN, Adeke AS, Versporten A, Goossens H, Igwe-Okomiso D, Okeke K, Azuogu BN, Onoh R. Point prevalence survey of antimicrobial prescription in a tertiary hospital in South East Nigeria: a call for improved antibiotic stewardship. J Global Antimicrob Resist. 2019;17:291–5.

D’Arcy N, Ashiru-Oredope D, Olaoye O, Afriyie D, Akello Z, Ankrah D, Asima DM, Banda DC, Barrett S, Brandish C, Brayson J, Benedict P, Dodoo CC, Garraghan F, Hoyelah J, Sr., Jani Y, Kitutu FE, Kizito IM, Labi AK, Mirfenderesky M, Murdan S, Murray C, Obeng-Nkrumah N, Olum WJ, Opintan JA, Panford-Quainoo E, Pauwels I, Sefah I, Sneddon J, St Clair Jones A, Versporten A. Antibiotic prescribing patterns in Ghana, Uganda, Zambia and Tanzania hospitals: results from the Global Point Prevalence Survey (G-PPS) on Antimicrobial Use and Stewardship interventions implemented. Antibiot (Basel). 2021;10(9).

Horumpende PG, Mshana SE, Mouw EF, Mmbaga BT, Chilongola JO, de Mast Q. Point prevalence survey of antimicrobial use in three hospitals in North-Eastern Tanzania. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2020;9(1):149.

Karanja PW, Kiunga A. Point prevalence survey and patterns of antibiotic use at Kirinyaga County Hospitals, Kenya. East Afr Sci. 2023;5(1):67–72.

Katyali D, Kawau G, Blomberg B, Manyahi J. Antibiotic use at a tertiary hospital in Tanzania: findings from a point prevalence survey. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2023;12(1):1–112.

Kiggundu R, Wittenauer R, Waswa JP, Nakambale HN, Kitutu FE, Murungi M, Okuna N, Morries S, Lawry LL, Joshi MP, Stergachis A, Konduri N. Point Prevalence Survey of Antibiotic Use across 13 hospitals in Uganda. Antibiot (Basel). 2022;11(2):199.

Kihwili L, Silago V, Francis EN, Idahya VA, Saguda ZC, Mapunjo S, Mushi MF, Mshana SE. A Point Prevalence Survey of Antimicrobial Use at Geita Regional Referral Hospital in North-Western Tanzania. Pharmacy. 2023;11(5):159.

Maina M, McKnight J, Tosas-Auguet O, Schultsz C, English M. Using treatment guidelines to improve antibiotic use: insights from an antibiotic point prevalence survey in Kenya. BMJ Global Health. 2021;6(1):e003836.

Momanyi L, Opanga S, Nyamu D, Oluka M, Kurdi A, Godman B. Antibiotic prescribing patterns at a leading referral hospital in Kenya: a point prevalence survey. J Res Pharm Pract. 2019;8(3):149–54.

Omulo S, Oluka M, Achieng L, Osoro E, Kinuthia R, Guantai A, Opanga SA, Ongayo M, Ndegwa L, Verani JR, Wesangula E, Nyakiba J, Makori J, Sugut W, Kwobah C, Osuka H, Njenga MK, Call DR, Palmer GH, VanderEnde D. Luvsansharav U-O. Point-prevalence survey of antibiotic use at three public referral hospitals in Kenya. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(6):e0270048–e.

Seni J, Mapunjo SG, Wittenauer R, Valimba R, Stergachis A, Werth BJ, Saitoti S, Mhadu NH, Lusaya E, Konduri N. Antimicrobial use across six referral hospitals in Tanzania: a point prevalence survey. BMJ open. 2020;10(12):e042819.

Dlamini NN, Meyer JC, Kruger D, Kurdi A, Godman B, Schellack N. Feasibility of using point prevalence surveys to assess antimicrobial utilisation in public hospitals in South Africa: a pilot study and implications. Hosp Pract (1995). 2019;47(2):88–95.

Talaat M, Saied T, Kandeel A, El-Ata GA, El-Kholy A, Hafez S, Osman A, Razik MA, Ismail G, El-Masry S, Galal R, Yehia M, Amer A, Calfee DP. A Point Prevalence Survey of Antibiotic Use in 18 hospitals in Egypt. Antibiot (Basel). 2014;3(3):450–60.

Acam J, Kuodi P, Medhin G, Makonnen E. Antimicrobial prescription patterns in East Africa: a systematic review. Syst Reviews. 2023;12(1):18.

Saleem Z, Godman B, Cook A, Khan MA, Campbell SM, Seaton RA, Siachalinga L, Haseeb A, Amir A, Kurdi A. Ongoing efforts to improve antimicrobial utilization in hospitals among African countries and implications for the future. Antibiotics. 2022;11(12):1824.

Sulis G, Adam P, Nafade V, Gore G, Daniels B, Daftary A, Das J, Gandra S, Pai M. Antibiotic prescription practices in primary care in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2020;17(6):e1003139.

Singh S, Sengupta S, Antony R, Bhattacharya S, Mukhopadhyay C, Ramasubramanian V, Sharma A, Sahu S, Nirkhiwale S, Gupta S. Variations in antibiotic use across India: multi-centre study through Global Point Prevalence survey. J Hosp Infect. 2019;103(3):280–3.

Vooss AT, Diefenthaeler HS. Evaluation of prescription indicators established by the WHO in Getúlio Vargas-RS. Brazilian J Pharm Sci. 2011;47:385–90.

Magill SS, Edwards JR, Bamberg W, Beldavs ZG, Dumyati G, Kainer MA, Lynfield R, Maloney M, McAllister-Hollod L, Nadle J. Multistate point-prevalence survey of health care–associated infections. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(13):1198–208.

Plachouras D, Kärki T, Hansen S, Hopkins S, Lyytikäinen O, Moro ML, Reilly J, Zarb P, Zingg W, Kinross P. Antimicrobial use in European acute care hospitals: results from the second point prevalence survey (PPS) of healthcare-associated infections and antimicrobial use, 2016 to 2017. Eurosurveillance. 2018;23(46):1800393.

Frenette C, Sperlea D, German GJ, Afra K, Boswell J, Chang S, Goossens H, Grant J, Lefebvre M-A, McGeer A. The 2017 global point prevalence survey of antimicrobial consumption and resistance in Canadian hospitals. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2020;9:1–9.

Abubakar U, Salman M. Antibiotic use among hospitalized patients in Africa: a systematic review of point prevalence studies. J Racial Ethnic Health Disparities. 2023:1–22.

Siachalinga L, Godman B, Mwita JC, Sefah IA, Ogunleye OO, Massele A, Lee I-H. Current antibiotic use among hospitals in the Sub-saharan Africa region; findings and implications. Infect Drug Resist. 2023:2179–90.

Acknowledgements

Authors thank College of Medicine and Health Science Wollo University who technically provided us a capacity building training on systematic review and meta-analysis.

Funding

There was no funding to conduct this systematic review and meta-analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MY, NA, AG, and MH, conceptualized and contrived the study, gathered scientific literature, censoriously appraised individual articles for inclusion, and extracted the data. MY and NA carried out the statistical analysis. MY synthesized the final manuscript for publication. All authors have made intellectual contributions to the work and approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors because it relies on primary studies.

Informed consent

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Disclaimer

This study is based on data from primary studies. The analysis, discussions, conclusions, opinions, and statements expressed in this text are those of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gobezie, M.Y., Tesfaye, N.A., Faris, A.G. et al. Surveillance of antimicrobial utilization in Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prescription rates, indications, and quality of use from point prevalence surveys. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 13, 101 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13756-024-01462-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13756-024-01462-w