Abstract

Background

Adherence to evidence-based standard treatment guidelines (STGs) enable healthcare providers to deliver consistently appropriate diagnosis and treatment. Irrational use of antimicrobials significantly contributes to antimicrobial resistance in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). The best available evidence is needed to guide healthcare providers on adherence to evidence-based implementation of STGs. This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to determine the pooled prevalence of adherence to evidence-based implementation of antimicrobial treatment guidelines among prescribers in SSA.

Methods

The review followed the JBI methodology for systematic reviews of prevalence data. CINAHL, Embase, PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science databases were searched with no language and publication year limitations. STATA version 17 were used for meta-analysis. The publication bias and heterogeneity were assessed using Egger’s test and the I2 statistics. Heterogeneity and publication bias were validated using Duval and Tweedie's nonparametric trim and fill analysis using the random-effect analysis. The summary prevalence and the corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI) of healthcare professionals’ compliance with evidence-based implementation of STG were estimated using random effect model. The review protocol has been registered with PROSPERO code CRD42023389011. The PRISMA flow diagram and checklist were used to report studies included, excluded and their corresponding section in the manuscript.

Results

Twenty-two studies with a total of 17,017 study participants from 14 countries in sub-Saharan Africa were included. The pooled prevalence of adherence to evidence-based implementation of antimicrobial treatment guidelines in SSA were 45%. The pooled prevalence of the most common clinical indications were respiratory tract (35%) and gastrointestinal infections (18%). Overall prescriptions per wards were inpatients (14,413) and outpatients (12,845). Only 391 prescribers accessed standard treatment guidelines during prescription of antimicrobials.

Conclusions

Healthcare professionals’ adherence to evidence-based implementation of STG for antimicrobial treatment were low in SSA. Healthcare systems in SSA must make concerted efforts to enhance prescribers access to STGs through optimization of mobile clinical decision support applications. Innovative, informative, and interactive strategies must be in place by the healthcare systems in SSA to empower healthcare providers to make evidence-based clinical decisions informed by the best available evidence and patient preferences, to ultimately improving patient outcomes and promoting appropriate antimicrobial use.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The World Health Organization (WHO) declared antimicrobial resistance (AMR) as a growing global health security and development threat that undermines the effectiveness of antimicrobial agents, threatening the ability to treat common microbial infections [1]. AMR poses a significant economic risk as it leads to higher patient care costs due to prolonged hospitalization, wastage of clinical and human resources, and a demand for the development of novel antimicrobial therapeutics [2, 3].

If preventative measures are not taken, the threat of will persist and result in a depletion of resources and an increase in morbidity and mortality on a global scale [4, 5]. Low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) suffer greater consequences due to insufficient funding, preventing access to costly second or third-line treatment alternatives [6]. AMR is often a result of misuse and overuse by the patient which is often attributable to inappropriate prescription by the health care provider (HCP) [7].

To combat inappropriate antimicrobial use, the development of standard treatment guidelines (STGs) has been included as part of the WHO’s Global Action Plan initiative; with this implementation, the WHO aims to set guidelines for the purchasing and prescription of antimicrobial medicine [8, 9]. STGs help to standardize treatment care by guiding the decisions of prescribers and determine the criteria for diagnosis, prevention, management, and treatment of disease [10, 11]. In order for STGs to be effective, they must be continually updated and made accessible to HCPs and patients [12, 13].

Studies have shown that when STGs are adhered to, mortality, morbidity, and the costs of health services related to corresponding illness are reduced [14, 15]. While the potential of STG use is promising, low rates of STG adherence have been documented in LMICs, where less than half of all patients were treated in accordance with STGs [16,17,18]. Countries in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) have made use of STGs, either developing their own based on local context, or adopting the WHO guidelines, altering them to be suitable for resource-limited settings [19,20,21,22,23].

Reasons for lack of adherence to STGs include a lack of skilled human resources, costs of the drugs, quality of the STGs, lack of accessibility to the drugs, lack of access to STGs, and inadequate training of prescribers [24, 25]. While the information presented gives us a glimpse of insight into the landscape of adherence to STGs in SSA, this information is not adequate to draw generalizable conclusion regarding patterns of adherence in the area, as most of the current reviews of evidence regarding STG adherence is from HICs [26, 27].

A scoping review that analyzed the overuse of medications in low resource settings found that only 10 out of 139 studies reported drivers of non-adherence-specific antimicrobial treatment guidelines [28, 29]. Thus, best available evidence on antimicrobial prescriptions in the context of SSA is imperative to understand the adherence of healthcare professionals to their respective STGs and the factors which influence compliance to standard antimicrobial treatment guidelines. This knowledge can be used to inform future interventions to improve prescribing behaviors in SSA in line with the WHOs Global Action Plan initiative’s goal to fill important knowledge gap on antimicrobial stewardship [30].

Therefore, this systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to determine the pooled prevalence of adherence to evidence-based implementation of antimicrobial treatment guidelines among prescribers in sub-Saharan Africa. The pooled data output obtained from this review would serve as region-specific and up-to-date evidence that contributes to comprehensive insights into gaps in the implementation of STGs at point of care and provides actionable recommendations for improvement. It would complement and enhance the knowledge gained from previous reviews by offering a more detailed and context-specific analysis.

Methods

The proposed review were conducted in accordance with the JBI methodology for systematic reviews of prevalence data [31]. The protocol has been registered with PROSPERO (CRD42023389011).

Search strategy

The database search targeted both published and unpublished studies. There was no language and publication year restrictions. A three-step search strategy were used in this review. First, an initial search of PubMed and CINAHL was undertaken, followed by an analysis of the titles, abstracts, and index terms of the articles. Second, all published and unpublished literature were searched using the identified keywords. Additional file 1: Appendix I shows the full search strategy for all databases. Third, the reference lists of all included primary studies were hand-searched for additional relevant studies. The Embase, Scopus, and Web of Science databases were searched. Moreover, Google Scholar, the Africa CDC and WHO platforms, dissertations, and thesis were searched for gray literature. Study authors were contacted if the full text is unavailable.

Study selection

Following the search, all identified citations were collated and uploaded into EndNote 20 and duplicates were removed. Descriptive observational and cross-sectional studies were included. Literature was eligible for inclusion if they reported adherence to STGs among prescribers in SSA. Studies which reported the prevalence of healthcare providers adherence to STGs as the main outcome were included. Literature that reported the clinical indications for which antimicrobials were prescribed for, access, availability, frequency of STG use was included. This review included studies conducted in both public and private health facilities in SSA. Protocols, systematic reviews, meta-analysis, randomized controlled trials, and studies conducted in high-income countries were excluded.

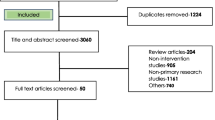

Titles and abstracts were assessed by two independent reviewers (MTB and VS) against the inclusion criteria. The full texts of potentially relevant studies were retrieved and the citation details were imported into the JBI System for the Unified Management, Assessment, and Review of Information (JBI SUMARI) [32]. The full texts of selected citations were assessed in detail against the inclusion criteria by independent reviewers (MTB and VS). Any disagreements that arose between the reviewers at each stage of the selection process were resolved through discussion with a third senior reviewer (SM). The results of the search, study inclusion and exclusion process were reported in full in the final systematic review and presented as a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram (PRISMA) (Fig. 1) [33]. PRISMA 2020 checklist were used to report each section of the manuscript with its corresponding pages (Additional file 1: Appendix II). Studies that reported healthcare providers adherence to evidence-based antimicrobial treatment guidelines in SSA were included. Literature including healthcare professionals from high-income countries, Middle East and North Africa were excluded. Systematic reviews, clinical trials, meta-analysis were excluded.

PRISMA flow diagram of included studies: Page et al. [96]

Operational definition

Evidence-based implementation of antimicrobial treatment guidelines

Refers to the systematic and rigorous applications of established clinical recommendations for the use of antimicrobial agents in the treatment of infectious diseases [34]. This approach relies on the uptake of the best available scientific evidence, clinical expertise, and patient preferences to inform healthcare providers about the most effective and safest strategies for prescribing antibiotics [35].

Adherence to evidence-based implementation of antimicrobial treatment guidelines

Refers to compliance with standard treatment guidelines (STG) for antimicrobial treatment at point of care provided that a consistently correct diagnoses and treatments that limit the irrational use of medicines and the negative health consequences that can occur as a result were in place [36, 37]. Adherence to guidelines denotes the degree of conformity between the knowledge, cognition and/or action of healthcare professionals who are involved in antimicrobial prescription pursuant with the recommendations of a guideline [38, 39]. By adhering to evidence-based guidelines, healthcare providers can optimize patient outcomes, enhance antimicrobial stewardship efforts, and contribute to the overall public health goal of combating antimicrobial resistance [40, 41].

Data extraction

The data extraction tool was prepared by MTB using excel spreadsheet. The data were extracted from included studies using the data extraction tool prepared by MTB. The tool includes variables such as the name of the author, publication year, study design, data collection period, sample size, study area, and the prevalence of adherence to standard treatment guidelines (STG) among health care providers. In addition, the tool consists of data on the clinical indications, access and availability of STG, frequency of use of STG. MTB and VS extracted the data. YS and SM cross-checked the extracted data for its validity and cleanness. Any disagreements between the reviewers were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer. Authors of the papers were contacted to request missing or additional data as required.

Assessment of methodological quality

Two independent reviewers critically appraised eligible studies for methodological quality using the JBI critical appraisal checklist for studies reporting prevalence data [42]. Study authors were contacted to request missing or additional data, if required. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion with a third senior reviewer. The results of the critical appraisal were reported in narrative and tabular format. A lower risk of bias (97%) observed after assessment (Table 1).

Data synthesis

Included studies were pooled in a statistical meta-analysis using STATA version 17.0. Effect size was expressed as a proportion with 95% confidence intervals around the summary estimate. Heterogeneity was assessed using the standard Chi-square I2 test. A random-effects model using the double arcsine transformation approach were used. Sensitivity analyses were conducted to test decisions made regarding the included studies. Visual examination of funnel plot asymmetry (Fig. 2) and Egger’s regression tests were used to check for publication bias [43]. A Forest plot with 95% CI were computed to estimate the pooled magnitude of adherence to evidence-based antimicrobial treatment guidelines among health care providers in sub-Saharan Africa.

Results

Search

Following the automatic removal of 408 literature as duplicates by EndNote 20, a total of 948 articles were obtained from PubMed, CINAHL, EMBASE, Google Scholar, and SCOPUS, and Web of Science databases. At the title/abstract screening phase (n = 816) and during the full-article screening (n = 110) articles were excluded. Accordingly, 43 studies were eligible for quality assessment. Finally, 22 studies were included in this meta-analysis (Fig. 1).

Study characteristics

The total sample size of this systematic review was 17,017, ranging from 75 in Nigeria [44] to 3713 in Ghana [45] (Table 1). Three studies were equally reported from Botswana [46,47,48] Ghana [45, 49, 50], and South Africa [51,52,53], respectively (Table 2). Two articles were obtained from Namibia [54, 55] and Tanzania [56, 57] (Table 2). Only one literature were obtained from Burkina Faso [58], Ethiopia [59], Kenya [60], Malawi [61], Nigeria [44], South Sudan [62], Sudan [63], Uganda [64], Zambia [65], respectively (Table 2).

The most common clinical indications for antibiotics were respiratory tract infection (RTI) reported by eleven studies [46, 49, 50, 52, 55, 56, 59, 61,62,63,64], followed by urinary tract infection (UTI) [45, 49, 56, 61], and gastrointestinal disease/infection [52, 62, 64, 65] which were equally indicated by four different studies (Table 3). Three articles described diarrhea [47, 55, 56] as clinical condition (Table 3). Equally two studies reported CNS [61, 65], co-infection [61, 62], Enteric infection [49, 61], Sepsis [61, 65], STIs [52, 53], and Malaria [56, 65] clinical indications for antibiotics, respectively (Table 3).

Public health officers (1616), nurses (731), medical doctors (196), and community health workers (151) were the distribution of STGs prescribers according to profession (Table 4). Educational qualification of prescribers was medical doctor (1676), clinical nurse (679), specialist (617), and internist (100), respectively (Table 4). A total of prescriptions made per ward were 12,845 (outpatient) and 14,413 (inpatient), respectively (Table 4). Three studies [54, 57, 63] reported that only 261 health care providers were aware regarding the use of STGs at point of clinical care (Table 4).

Only three studies have reported the frequency of STG use by prescribers [49, 51, 54], out of which two articles described that healthcare professionals never used STG [49, 54] (Table 4). Six articles [49, 51, 54, 55, 57, 63] revealed that 391 health care providers accessed STGs during prescription (Table 4). Only two literatures [54, 57] reported that continuous professional development (CPD) training on compliance to STGs were delivered to 213 health care workers (Table 4). The review was conducted on studies that used the cross-sectional designs (Table 4).

Pooled prevalence of implementation of evidence-based antimicrobial treatment guidelines

The pooled prevalence of adherence to evidence-based implementation of antimicrobial treatment guidelines were 45.23% (95% CI 32.75–58.01%) (Fig. 3).

The pooled prevalence of RTI, UTI, and GI

The sample size of RTI ranges from 56 [63] to 902 [64] (Table 3). The pooled prevalence of RTI were 34.84 (95% CI 29.00–40.90%) (Fig. 4). The lowest and the highest infection from gastrointestinal diseases were 37 [65] and 730 [64] (Table 3). The pooled prevalence GI were 17.95% (95% CI 11.65–25.25%) (Fig. 5).

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to determine the pooled estimate of implementation of standard treatment guidelines among the prescribers in SSA. A total of 17,017 healthcare professionals who prescribed antimicrobials participated in 22 studies reported from 14 in SSA. The pooled prevalence of adherence to evidence-based antimicrobial treatment guidelines at point of care in SSA were 45%. Lower adherence to evidence-based antimicrobial treatment guidelines can be attributed to healthcare provider-related factors, such as lack of awareness or knowledge about the guidelines [66], doubt regarding their applicability to individual patients [67], limited availability or accessibility of guidelines [68], inadequate resources or infrastructure to support guideline implementation [69], and competing priorities within healthcare settings [70], and patient preferences [71]. Addressing these barriers through targeted educational initiatives, organizational support, and shared decision-making approaches can help improve adherence to evidence-based antimicrobial treatment guidelines and promote optimal patient care [72,73,74].

This review indicated that only 261 prescribers have awareness regarding the implementation of STG in routine clinical care. Lower awareness among prescribers regarding the use of STG at the point of care can have significant implications for patient care and outcomes [75]. It can lead to variations in clinical practices, with prescribers deviating from evidence-based recommendations [76]. This can result in inconsistent and potentially suboptimal treatment decisions, compromising patient safety and quality of care [77]. Inadequate awareness of guidelines contributes to overuse or inappropriate use of antimicrobial agents, leading to increased healthcare costs, antimicrobial resistance, and adverse drug reactions [78]. Implementation of decision support tools can help improve adherence to guidelines, enhance patient outcomes, and promote the judicious use of antimicrobial treatments [79, 80].

This study revealed that only 391 healthcare providers in SSA accessed STG when they prescribed antimicrobials to patients. Limited access to STG for healthcare providers can lead to variability and inconsistency in prescribing practices [81]. This can result in suboptimal or inappropriate use of antimicrobial agents, potentially compromising patient safety and treatment efficacy [82]. The absence of guidelines can hinder the dissemination of evidence-based recommendations, impeding the implementation of best practices and advancements in antimicrobial stewardship [83, 84]. Healthcare providers may face challenges in keeping up with the rapidly evolving field of infectious diseases and antimicrobial resistance without access to updated guidelines [85].

Healthcare providers in SSA commonly treated cases of respiratory tract infection (35%) and gastrointestinal diseases (18%). Respiratory tract (35%) and gastrointestinal (18%) infections are highly treated clinical indications in SSA. This could be attributed to their significant burden due to easy transmissibility and environmental factors [86, 87].

Limitations of the study

This systematic review and meta-analysis involved cross-sectional studies that comes with limitations related to causality, selection bias, heterogeneity, and the inability to capture temporal and dynamic trends. To overcome these limitations and obtain a more comprehensive understanding of adherence to implementation of evidence-based STGs, future research could consider incorporating other study designs, such as longitudinal studies or randomized controlled trials, in addition to cross-sectional data.

Conclusion

Healthcare professionals’ adherence to evidence-based implementation of standard treatment guidelines for antimicrobial treatment were low in sub-Saharan Africa. Healthcare systems in sub-Saharan Africa must make concerted efforts to enhance prescribers access to standard treatment guidelines through the implementation of mobile clinical decision support applications to optimize compliance with standard treatment guidelines. Innovative, informative, and interactive strategies must be in place by the healthcare systems in sub-Saharan Africa to empower healthcare providers to make evidence-based clinical decisions informed by the best available evidence and patient preferences, to ultimately improving patient outcomes and promoting appropriate antimicrobial use.

Implications for policy and practice

The implementation of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for antimicrobial treatment involves the systematic integration of the best available evidence into clinical decision-making and patient care [88, 89]. These guidelines are developed based on rigorous research and aim to provide healthcare practitioners with recommendations on the appropriate use of antimicrobial agents for specific infections [90]. The implementation process includes raising awareness about the guidelines, promoting their adoption and acceptance among healthcare professionals, providing education and training on their content and implementation strategies, and addressing barriers and challenges to their implementation [91, 92]. By effectively implementing these guidelines, healthcare systems can optimize antimicrobial therapy, improve patient outcomes, prevent antimicrobial resistance, and ensure the judicious use of these critical medications in sub-Saharan Africa [93,94,95].

Availability of data and materials

The data sets during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AMR:

-

Antimicrobial resistance

- AHRI:

-

The Armauer Hansen Research Institute

- HCP:

-

Health Care Providers/Professionals

- JBI:

-

The Joanna Briggs Institute

- JBI SUMARI:

-

The Joanna Briggs Institute’s System for the Unified Management, Assessment, and Review of Information (SUMARI)

- LMICs:

-

Low- and middle-income countries

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses

- PROSPERO:

-

International Prospective Registry of Systematic Reviews

- SDG:

-

Sustainable development goal

- SSA:

-

Sub-Saharan Africa

- STGs:

-

Standard Treatment Guidelines

- WHO:

-

The World Health Organization

References

Zhou N, Cheng Z, Zhang X, Lv C, Guo C, Liu H, Dong K, Zhang Y, Liu C, Chang Y-F, et al. Global antimicrobial resistance: a system-wide comprehensive investigation using the Global One Health Index. Infect Dis Poverty. 2022;11(1):92.

Shrestha P, Cooper BS, Coast J, Oppong R, Do Thi Thuy N, Phodha T, Celhay O, Guerin PJ, Wertheim H, Lubell Y. Enumerating the economic cost of antimicrobial resistance per antibiotic consumed to inform the evaluation of interventions affecting their use. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2018;7(1):98.

Chakaya J, Khan M, Ntoumi F, Aklillu E, Fatima R, Mwaba P, Kapata N, Mfinanga S, Hasnain SE, Katoto P, et al. Global tuberculosis report 2020—reflections on the global TB burden, treatment and prevention efforts. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;113(Suppl 1):S7-s12.

Dadgostar P. Antimicrobial resistance: implications and costs. Infect Drug Resist. 2019;12:3903–10.

Ayukekbong JA, Ntemgwa M, Atabe AN. The threat of antimicrobial resistance in developing countries: causes and control strategies. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2017;6:47.

Jim ON. Antimicrobial resistance: tackling a crisis for the health and wealth of nations. Rev Antimicrob Resist. 2014.

Nahar P, Unicomb L, Lucas PJ, Uddin MR, Islam MA, Nizame FA, Khisa N, Akter SMS, Rousham EK. What contributes to inappropriate antibiotic dispensing among qualified and unqualified healthcare providers in Bangladesh? A qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):656.

Kamere N, Garwe ST, Akinwotu OO, Tuck C, Krockow EM, Yadav S, Olawale AG, Diyaolu AH, Munkombwe D, Muringu E, et al. Scoping review of national antimicrobial stewardship activities in eight African countries and adaptable recommendations. Antibiotics (Basel). 2022;11(9):1149.

Cuevas C, Batura N, Wulandari LPL, Khan M, Wiseman V. Improving antibiotic use through behaviour change: a systematic review of interventions evaluated in low- and middle-income countries. Health Policy Plan. 2021;36(5):754–73.

Lahariya C, Sharma S, Agnani M, de Graeve H, Srivastava JN, Bekedam H. Attributes of standard treatment guidelines in clinical settings and public health facilities in India. Indian J Commun Med. 2022;47(3):336.

Yan M, Chen L, Yang M, Zhang L, Niu M, Wu F, Chen Y, Song Z, Zhang Y, Li J. Evidence mapping of clinical practice guidelines recommendations and quality for depression in children and adolescents. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2022;32:2091–108.

Herbella FA, Patti MG, Filho RM, Serodio AM, Adão D, Bastos IBDA, Soares FR, Wagar III C. How changes in treatment guidelines affect the standard of care: ethical opinions using the Chicago 4.0 classification for esophageal motility disorders as example. Foregut. 2022;2(2):111–5.

Burgers J, van der Weijden T, Grol R. Clinical practice guidelines as a tool for improving patient care. In: Improving patient care: the implementation of change in health care. 2020. pp. 103–129.

Crimmins EM, Beltrán-Sánchez H. Mortality and morbidity trends: is there compression of morbidity? J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2011;66(1):75–86.

Kruk ME, Gage AD, Joseph NT, Danaei G, García-Saisó S, Salomon JA. Mortality due to low-quality health systems in the universal health coverage era: a systematic analysis of amenable deaths in 137 countries. Lancet. 2018;392(10160):2203–12.

Olayemi E, Asare EV, Benneh-Akwasi Kuma AA. Guidelines in lower-middle income countries. Br J Haematol. 2017;177(6):846–54.

Docherty M, Shaw K, Goulding L, Parke H, Eassom E, Ali F, Thornicroft G. Evidence-based guideline implementation in low and middle income countries: lessons for mental health care. Int J Ment Heal Syst. 2017;11(1):8.

Mondéjar EF. Considerations on the low adherence to clinical practice guidelines. Med Intensiva. 2017;41:265–6.

Odoch WD, Senkubuge F, Masese AB, Hongoro C. How are global health policies transferred to sub-Saharan Africa countries? A systematic critical review of literature. Glob Health. 2022;18(1):25.

Mhazo AT, Maponga CC. Agenda setting for essential medicines policy in sub-Saharan Africa: a retrospective policy analysis using Kingdon’s multiple streams model. Health Res Policy Syst. 2021;19(1):72.

Stegmann J-U, Jusot V, Menang O, Gardiner G, Vesce S, Volpe S, Ndalama A, Adou F, Ofori-Anyinam O, Oladehin O, et al. Challenges and lessons learned from four years of planning and implementing pharmacovigilance enhancement in sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):1568.

Chakkalakal RJ, Cherlin E, Thompson J, Lindfield T, Lawson R, Bradley EH. Implementing clinical guidelines in low-income settings: a review of literature. Glob Public Health. 2013;8(7):784–95.

Heen AF, Vandvik PO, Brandt L, Montori VM, Lytvyn L, Guyatt G, Quinlan C, Agoritsas T. A framework for practical issues was developed to inform shared decision-making tools and clinical guidelines. J Clin Epidemiol. 2021;129:104–13.

Sarwar MR, Saqib A, Iftikhar S, Sadiq T. Antimicrobial use by WHO methodology at primary health care centers: a cross sectional study in Punjab, Pakistan. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):492.

Sijbom M, Büchner FL, Saadah NH, Numans ME, de Boer MG. Determinants of inappropriate antibiotic prescription in primary care in developed countries with general practitioners as gatekeepers: a systematic review and construction of a framework. BMJ Open. 2023;13(5): e065006.

Perumal-Pillay VA, Suleman F. Selection of essential medicines for South Africa—an analysis of in-depth interviews with national essential medicines list committee members. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):17.

Peacocke EF, Myhre SL, Foss HS, Gopinathan U. National adaptation and implementation of WHO Model List of Essential Medicines: a qualitative evidence synthesis. PLoS Med. 2022;19(3): e1003944.

Albarqouni L, Hoffmann T, Straus S, Olsen NR, Young T, Ilic D, Shaneyfelt T, Haynes RB, Guyatt G, Glasziou P. Core competencies in evidence-based practice for health professionals: consensus statement based on a systematic review and Delphi Survey. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(2):e180281–e180281.

Albarqouni L, Palagama S, Chai J, Sivananthajothy P, Pathirana T, Bakhit M, Arab-Zozani M, Ranakusuma R, Cardona M, Scott A, et al. Overuse of medications in low- and middle-income countries: a scoping review. Bull World Health Organ. 2023;101(1):36–61d.

Hamers RL, Dobreva Z, Cassini A, Tamara A, Lazarus G, Asadinia KS, Burzo S, Olaru ID, Dona D, Emdin F, et al. Global knowledge gaps on antimicrobial resistance in the human health sector: a scoping review. Int J Infect Dis. 2023;134:142–9.

Aromataris E, Stern C, Lockwood C, Barker TH, Klugar M, Jadotte Y, Evans C, Ross-White A, Lizarondo L, Stephenson M, et al. JBI series paper 2: tailored evidence synthesis approaches are required to answer diverse questions: a pragmatic evidence synthesis toolkit from JBI. J Clin Epidemiol. 2022;150:196–202.

Munn Z, Aromataris E, Tufanaru C, Stern C, Porritt K, Farrow J, Lockwood C, Stephenson M, Moola S, Lizarondo L. The development of software to support multiple systematic review types: the Joanna Briggs Institute System for the Unified Management, Assessment and Review of Information (JBI SUMARI). JBI Evid Implement. 2019;17(1):36–43.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int J Surg. 2021;88: 105906.

Gagliardi AR, Armstrong MJ, Bernhardsson S, Fleuren M, Pardo-Hernandez H, Vernooij RW, Willson M, Brereton L, Lockwood C, Amer YS. The Clinician Guideline Determinants Questionnaire was developed and validated to support tailored implementation planning. J Clin Epidemiol. 2019;113:129–36.

Titler MG. The evidence for evidence-based practice implementation. In: Patient safety and quality: an evidence-based handbook for nurses. 2008.

Borek AJ, Campbell A, Dent E, Moore M, Butler CC, Holmes A, Walker AS, McLeod M, Tonkin-Crine S, Anyanwu PE, et al. Development of an intervention to support the implementation of evidence-based strategies for optimising antibiotic prescribing in general practice. Implement Sci Commun. 2021;2(1):104.

Steels S, van Staa TP. The role of real-world data in the development of treatment guidelines: a case study on guideline developers’ opinions about using observational data on antibiotic prescribing in primary care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):942.

Hasenbein U, Wallesch CW. What is “adherence to guidelines”? Theoretical and methodological considerations on a new concept for health system research and quality management. Gesundheitswesen. 2007;69(8–9):427–37.

Foxlee ND, Townell N, Heney C, McIver L, Lau CL. Strategies used for implementing and promoting adherence to antibiotic guidelines in low-and lower-middle-income countries: a systematic review. Trop Med Infect Disease. 2021;6(3):166.

Kakkar AK, Shafiq N, Singh G, Ray P, Gautam V, Agarwal R, Muralidharan J, Arora P. Antimicrobial stewardship programs in resource constrained environments: understanding and addressing the need of the systems. Front Public Health. 2020;8:140.

Adhikari P, Director M, Bhumiratana A, Acharya S, Acharya U, Pant S, Silwal S, Dawadi P, Koirala J, Gyanwali P. 1779. An assessment of antibiotic treatment guideline adherence for common infections in a Tertiary Care Hospital with an established Antimicrobial Stewardship Program in Kathmandu, Nepal. In: Open Forum Infectious Diseases: 2022: Oxford University Press USA; 2022: ofac492. 1409.

Munn Z, Moola S, Lisy K, Riitano D, Tufanaru C. Methodological guidance for systematic reviews of observational epidemiological studies reporting prevalence and cumulative incidence data. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):147–53.

Copas J, Shi JQ. A sensitivity analysis for publication bias in systematic reviews. Stat Methods Med Res. 2001;10(4):251–65.

Bello CB. Adherence to medication administration guidelines among nurses in a health facility in South-West Nigeria. Pan Afr Med J. 2021;40(1):56.

Owusu H, Thekkur P, Ashubwe-Jalemba J, Hedidor GK, Corquaye O, Aggor A, Steele-Dadzie A, Ankrah D. Compliance to guidelines in prescribing empirical antibiotics for individuals with uncomplicated urinary tract infection in a Primary Health Facility of Ghana, 2019–2021. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(19):12413.

Boonstra E, Lindbæk M, Ngome E. Adherence to management guidelines in acute respiratory infections and diarrhoea in children under 5 years old in primary health care in Botswana. Int J Qual Health Care. 2005;17(3):221–7.

Boonstra E, Lindbaek M, Khulumani P, Ngome E, Fugelli P. Adherence to treatment guidelines in primary health care facilities in Botswana. Trop Med Int Health. 2002;7(2):178–86.

Mashalla Y, Setlhare V, Massele A, Sepako E, Tiroyakgosi C, Kgatlwane J, Chuma M, Godman B. Assessment of prescribing practices at the primary healthcare facilities in Botswana with an emphasis on antibiotics: findings and implications. Int J Clin Pract. 2017; 71(12).

Prah J, Kizzie-Hayford J, Walker E, Ampofo-Asiama A. Antibiotic prescription pattern in a Ghanaian primary health care facility. Pan Afr Med J. 2017;28(1):214.

Sefah IA, Essah DO, Kurdi A, Sneddon J, Alalbila TM, Kordorwu H, Godman B. Assessment of adherence to pneumonia guidelines and its determinants in an ambulatory care clinic in Ghana: findings and implications for the future. JAC Antimicrob Resist. 2021;3(2):dlab080.

Govender T, Suleman F, Perumal-Pillay VA. Evaluating the implementation of the standard treatment guidelines (STGs) and essential medicines list (EML) at a public South African tertiary institution and its associated primary health care (PHC) facilities. J Pharm Policy Pract. 2021;14(1):105.

Gasson J, Blockman M, Willems B. Antibiotic prescribing practice and adherence to guidelines in primary care in the Cape Town Metro District, South Africa. S Afr Med J. 2018;108(4):304–10.

Matsitse TB, Helberg E, Meyer JC, Godman B, Massele A, Schellack N. Compliance with the primary health care treatment guidelines and the essential medicines list in the management of sexually transmitted infections in correctional centres in South Africa: findings and implications. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2017;15(10):963–72.

Niaz Q, Godman B, Campbell S, Kibuule D. Compliance to prescribing guidelines among public health care facilities in Namibia; findings and implications. Int J Clin Pharm. 2020;42(4):1227–36.

Akpabio E, Sagwa E, Mazibuko G, Kagoya H, Niaz Q, Mabirizi D. Assessment of compliance of outpatient prescribing with the Namibia standard treatment guidelines in Public Sector Health Facilities. Windhoek: MSH-Namibia. 2014.

Wiedenmayer K, Ombaka E, Kabudi B, Canavan R, Rajkumar S, Chilunda F, Sungi S, Stoermer M. Adherence to standard treatment guidelines among prescribers in primary healthcare facilities in the Dodoma region of Tanzania. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):272.

Budimu A, Emidi B, Mkumbaye S, Kajeguka DC. Adherence, awareness, access, and use of standard diagnosis and treatment guideline for malaria case management among healthcare workers in Meatu, Tanzania. J Trop Med. 2020.

Krause G, Borchert M, Benzler J, Heinmüller R, Kaba I, Savadogo M, Siho N, Diesfeld H. Rationality of drug prescriptions in rural health centres in Burkina Faso. Health Policy Plan. 1999;14(3):291–8.

Eticha EM, Gemechu WD. Adherence to guidelines for assessment and empiric antibiotics recommendations for community-acquired pneumonia at ambo university referral hospital: prospective observational study. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2021;15:467–73.

Obegi EB. Antimicrobial prescribing patterns in critical care and compliance to guideline at the Kenyatta National Hospital. University of Nairobi; 2020.

Sibande GT, Banda NPK, Moya T, Siwinda S, Lester R. Antibiotic guideline adherence by Clinicians in medical wards at Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital (QECH), Blantyre Malawi. Malawi Med J. 2022;34(1):3–8.

Otim ME, Demaya DK, Al Marzouqi A, Mukasa J. Are antibiotics prescribed to inpatients according to recommended standard guidelines in South Sudan? A retrospective cross-sectional study in Juba Teaching Hospital. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2021;14:2871–9.

Nehal AM Musa HMHaMMAM, Musa NAM, Harron HM, Maatoug MMA. Assessment of medical doctors’ adherence to national protocol for treatment of severe pneumonia in underfive children admitted to Wad-Medani pediatric teaching hospital, Gezira State, Sudan (2018). Clin Pract. 2019; 16(S1): 1381–1388. https://doi.org/10.4172/clinical-practice.1000405.

Obakiro SB, Napyo A, Wilberforce MJ, Adongo P, Kiyimba K, Anthierens S, Kostyanev T, Waako P, Van Royen P. Are antibiotic prescription practices in Eastern Uganda concordant with the national standard treatment guidelines? A cross-sectional retrospective study. J Global Antimicrob Resist. 2022;29:513–9.

Miyanda PM, Siame B, Chisulo AC. Antibiotic prescribing patterns at a level one hospital using national treatment guidelines prescribing indicators in Zambia. J Prevent Rehabil Med. 2022;4(1):59–64.

Saunders BI. Inappropriate antibiotic use: a survey of provider prescribing behaviors. 2020.

Wehking F, Debrouwere M, Danner M, Geiger F, Buenzen C, Lewejohann J-C, Scheibler F. Impact of shared decision making on healthcare in recent literature: a scoping review using a novel taxonomy. J Public Health 2023:1–12.

Correa VC, Lugo-Agudelo LH, Aguirre-Acevedo DC, Contreras JAP, Borrero AMP, Patiño-Lugo DF, Valencia DAC. Individual, health system, and contextual barriers and facilitators for the implementation of clinical practice guidelines: a systematic metareview. Health Res Policy Syst. 2020;18:1–11.

Tian C, Xu M, Wang Y, Lu J, Wang Y, Xue J, Ge L. Barriers and strategies of clinical practice guideline implementation in China: aggregated analysis of 16 cross-sectional surveys. J Public Health. 2023:1–14.

Saluja K, Reddy KS, Wang Q, Zhu Y, Li Y, Chu X, Li R, Hou L, Horsley T, Carden F. Improving WHO’s understanding of WHO guideline uptake and use in Member States: a scoping review. Health Res Policy Syst. 2022;20(1):1–21.

Blackwood J, Armstrong MJ, Schaefer C, Graham ID, Knaapen L, Straus SE, Urquhart R, Gagliardi AR. How do guideline developers identify, incorporate and report patient preferences? An international cross-sectional survey. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20:1–10.

Engle RL, Mohr DC, Holmes SK, Seibert MN, Afable M, Leyson J, Meterko M. Evidence-based practice and patient-centered care: doing both well. Health Care Manage Rev. 2021;46(3):174.

Melnyk BM, Gallagher-Ford L, Fineout-Overholt E. Implementing the evidence-based practice (EBP) competencies in healthcare: a practical guide for improving quality, safety, and outcomes: Sigma Theta Tau; 2016.

Cullen L, Hanrahan K, Farrington M, Tucker S, Edmonds S. Evidence-based practice in action: comprehensive strategies, tools, and tips from University of Iowa Hospitals & Clinics: Sigma Theta Tau; 2022.

Saha SK, Thursky K, Kong DC, Mazza D. A novel GPPAS model: guiding the implementation of antimicrobial stewardship in primary care utilising collaboration between general practitioners and community pharmacists. Antibiotics. 2022;11(9):1158.

Fadoul Y, Haddad C, Habib J, Zoghbi M. Pharmaceutical brochures in Lebanon: do they meet WHO recommendations? BMC Primary Care. 2022;23(1):1–8.

Karasneh RA, Al-Azzam SI, Ababneh M, Al-Azzeh O, Al-Batayneh OB, Muflih SM, Khasawneh M, Khassawneh A-RM, Khader YS, Conway BR. Prescribers’ knowledge, attitudes and behaviors on antibiotics, antibiotic use and antibiotic resistance in Jordan. Antibiotics. 2021;10(7):858.

Al Rahbi F, Al Salmi I, Khamis F, Al Balushi Z, Pandak N, Petersen E, Hannawi S. Physicians’ attitudes, knowledge, and practices regarding antibiotic prescriptions. J Global Antimicrob Resist. 2023;32:58–65.

Rawson T, Moore L, Hernandez B, Charani E, Castro-Sanchez E, Herrero P, Hayhoe B, Hope W, Georgiou P, Holmes A. A systematic review of clinical decision support systems for antimicrobial management: are we failing to investigate these interventions appropriately? Clin Microbiol Infect. 2017;23(8):524–32.

Eudaley ST, Mihm AE, Higdon R, Jeter J, Chamberlin SM. Development and implementation of a clinical decision support tool for treatment of uncomplicated urinary tract infections in a family medicine resident clinic. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2019;59(4):579–85.

Steffens E, Quintens C, Derdelinckx I, Peetermans WE, Van Eldere J, Spriet I, Schuermans A. Outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy and antibiotic stewardship: opponents or teammates? Infection. 2019;47:169–81.

Venkatesan AM, Kundu S, Sacks D, Wallace MJ, Wojak JC, Rose SC, Clark TW, d’Othee BJ, Itkin M, Jones RS. Practice guideline for adult antibiotic prophylaxis during vascular and interventional radiology procedures. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2010;21(11):1611–30.

Fischer F, Lange K, Klose K, Greiner W, Kraemer A. Barriers and strategies in guideline implementation—a scoping review. Healthcare (Basel). 2016;4(3):36.

McArthur C, Bai Y, Hewston P, Giangregorio L, Straus S, Papaioannou A. Barriers and facilitators to implementing evidence-based guidelines in long-term care: a qualitative evidence synthesis. Implement Sci. 2021;16(1):70.

Pereira VC, Silva SN, Carvalho VKS, Zanghelini F, Barreto JOM. Strategies for the implementation of clinical practice guidelines in public health: an overview of systematic reviews. Health Res Policy Syst. 2022;20(1):13.

Serigstad S, Markussen DL, Ritz C, Ebbesen MH, Knoop ST, Kommedal Ø, Heggelund L, Ulvestad E, Bjørneklett RO, Grewal HMS, et al. The changing spectrum of microbial aetiology of respiratory tract infections in hospitalized patients before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Infect Dis. 2022;22(1):763.

Natarajan A, Zlitni S, Brooks EF, Vance SE, Dahlen A, Hedlin H, Park RM, Han A, Schmidtke DT, Verma R, et al. Gastrointestinal symptoms and fecal shedding of SARS-CoV-2 RNA suggest prolonged gastrointestinal infection. Med. 2022;3(6):371-387.e379.

Foxlee ND, Townell N, Heney C, McIver L, Lau CL. Strategies used for implementing and promoting adherence to antibiotic guidelines in low- and lower-middle-income countries: a systematic review. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2021;6(3):166.

Peters S, Sukumar K, Blanchard S, Ramasamy A, Malinowski J, Ginex P, Senerth E, Corremans M, Munn Z, Kredo T, et al. Trends in guideline implementation: an updated scoping review. Implement Sci. 2022;17(1):50.

Wu S, Tannous E, Haldane V, Ellen ME, Wei X. Barriers and facilitators of implementing interventions to improve appropriate antibiotic use in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review based on the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. Implement Sci. 2022;17(1):30.

Elaine L, Patricia L-W, Cliona OR, Eileen S, Jonathan D, Colm OT, Michael OC, Mark C, Francis B, Martina H, et al. Evidence-based practice education for healthcare professions: an expert view. BMJ Evid Based Med. 2019;24(3):103.

Skivington K, Matthews L, Simpson SA, Craig P, Baird J, Blazeby JM, Boyd KA, Craig N, French DP, McIntosh E, et al. A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: update of Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2021;374: n2061.

O'Brien EA-O, Clyne B, Smith SA-O, O'Herlihy N, Harkins V, Wallace E. A scoping review protocol of evidence-based guidance and guidelines published by general practitioner professional organisations. LID-53. (2515–4826 (Electronic)).

Kredo T, Bernhardsson S, Machingaidze S, Young T, Louw Q, Ochodo E, Grimmer K. Guide to clinical practice guidelines: the current state of play. Int J Qual Health Care. 2016;28(1):122–8.

Chan WV, Pearson TA, Bennett GC, Cushman WC, Gaziano TA, Gorman PN, Handler J, Krumholz HM, Kushner RF, MacKenzie TD, et al. ACC/AHA special report: clinical practice guideline implementation strategies: a summary of systematic reviews by the NHLBI implementation science work group. Circulation. 2017;135(9):e122–37.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the Ethiopian Evidence Based Health Care and Development Centre, A JBI Centre of Excellence, and the Armauer Hansen Research Institute for proving the training on comprehensive systematic review, meta-analysis, and access to databases.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MTB, SM and VS; was involved in a principal role in the conception of ideas, developing methodologies, writing the manuscript. MTB and VS, were involved in the analysis while MW, YS, and ZEK participated in the analysis, interpretation and writing. YS and ZEK involved in proofreading, and writing. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable. Unlike primary studies, systematic reviews does not include the collection of deeply personal, sensitive, and confidential information from the study participants. Systematic reviews involves the use of publicly accessible data as evidence and are not required to seek an institutional ethics approval before commencement.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that this study is free of any competing financial and non-financial interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1

: Appendix I: Search strategy. Appendix II: PRISMA 2020 Checklist.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Boltena, M.T., Woldie, M., Siraneh, Y. et al. Adherence to evidence-based implementation of antimicrobial treatment guidelines among prescribers in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J of Pharm Policy and Pract 16, 137 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40545-023-00634-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40545-023-00634-0