Abstract

The uncertain production-inventory problem with deteriorating items is investigated and an optimal control model is developed in the present paper. The uncertain production-inventory problem is perturbed by an uncertain canonical process. Based on uncertainty theory, an optimistic-value optimal-based control model is established. The present study aims to find the optimistic value of revenue at a certain confidence level. The uncertainty theory is used to obtain the equation of optimality. Using the Hamilton–Jacobi–Bellman principle, a nonlinear partial differential equation that has to be satisfied by a value function is obtained. Assuming a specific form of the solution, backsubstituting the partial differential equation to find functions of time is conducted, and the functions are then used to solve the partial differential equation. Numerical experiments with different demand functions are used to assess the feasibility of this model and this method.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

With the development of economic globalization, manufacturing-inventory management plays an important role in the production and operation of enterprises. The production-inventory problem has aroused increasing attention in recent years. Making reasonable strategies is a matter of concern to enterprises. Optimal control theory is one of the main branches of modern control theory, which mainly focuses on the basic conditions and comprehensive methods of performance optimization for control systems. Thus far, many scholars have used optimal control theory to address the production-inventory problem. Dobos and Kistner [15] investigated strategies of optimizing production-inventory management for a reverse logistics system, and applied a modified forward Arrow–Karlin algorithm to the construction of an optimal trajectory. Dobos [14] investigated a reverse logistics system with special structure where the demand rate and rate of return from used items were given functions. The model deals with an optimal control problem with two state variables and three control variables. The aim of the model is to minimize the sum of secondary deviations in inventory level and manufacturing, remanufacturing, and disposal rates. Khmelnitsky and Gerchak [27] proposed an optimal control model for a production system with inventory-level-dependent demand, and obtained three possible singular regimes through application of the maximum principle. Yang [55] investigated a two-warehouse inventory problem for deteriorating items with constant demand rate and supply shortage under inflation, and showed that the proposed model was less expensive to operate than the traditional one if the inflation rate was nonnegative. Tadj et al. [50] used an optimal control method to obtain the optimal production rate in a production-inventory system with deteriorating items, and proposed analytical solutions to a cost-minimization problem and a profit-maximization problem. Hedjar et al. [20] studied a periodic-review inventory system with deteriorating items and proposed the self-tuning optimal control scheme. Benhadid et al. [3] adopted an optimal control method to solve two production-inventory models with deteriorating items and dynamic costs, and derived explicit optimal control policies. Alshamrani and El-Gohary [1] established an optimal control model for a two-item inventory system with different types of deterioration, and obtained the optimal solution based on Pontryagin’s principle. Li [33, 34] proposed optimal control models of a production-maintenance system with deteriorating items, and applied Pontryagin’s principle to solve the models. Pan and Li [39] investigated a stochastic production inventory system with deteriorating items and environmental constraints, and used the Hamilton–Jacobi–Bellman equation to solve the stochastic model. Roul et al. [41] developed an optimal control model for a multiitem production-inventory system with known dynamic demands, and derived several particular cases from the general model. Gayon et al. [19] investigated an optimal control problem of a production-inventory system with product returns and two disposal options, and proved that the optimal policy was a threshold policy with three policy parameters. Azoury and Miyaoka [2] studied a production-inventory system where the demand was a compound Poisson process, and derived the steady-state distribution and the exact expression. Dizbin and Tan [13] proposed a matrix geometric method to determine the optimal thresholds for production-inventory systems, and the results suggested that an effective production-control policy must consider the correlation between service and demand. Das et al. [8] proposed a production-inventory model with a deteriorating item, and a hybrid genetic algorithm was designed. Das et al. [9] developed a production-inventory model with deteriorating items under permissible delay in payments, and an improved genetic algorithm was applied to solve the problem. Das et al. [10] considered a production-inventory model with random machine failure, and the global criteria method was used to solve the multiobjective optimization problem.

As the scale of the supply chain continues to expand, the market environment becomes more intricate, the uncertainties in the supply chain are increasing, and the operation becomes more difficult. Uncertainty in the supply chain means that a decision is made with outcomes that are unknown or unpredictable in advance. The manufacturing uncertainty mainly comes from the inability to ensure a smooth manufacturing process, which may be caused by interruptions, delays, and unreasonable production process design as a result of equipment failure. In addition, nonconforming products and workers’ wrong operations are also uncertain factors. Demand uncertainty mainly comes from market changes, customers’ purchasing ability, pressure from new products, and price fluctuations, etc. Due to the complexity of the situation, there is a lack of historical data for many uncertain factors, or the existing data is not credible. In this case, it is difficult to obtain the probability distribution of these uncertain factors and only experienced experts can assess the degree of belief to be placed in these events. To address the degrees of belief, the uncertainty theory was proposed by Liu [35] and later refined by Liu [38] on the basis of normality, duality, subadditivity, and product axioms. Since there are many uncertain factors that are in short supply in historical data in reality, the uncertainty theory exhibits its incomparable superiority in solving such problems. Nowadays, the uncertainty theory has developed into a branch of axiomatic mathematics, e.g., uncertain differential equation [16, 17, 21, 22, 49, 53, 56, 57], uncertain programming [5, 18, 24, 40, 51, 52, 54, 61], uncertain supply chain [4, 23, 25, 26], uncertain scheduling [42–47], uncertain control [6, 7, 11, 12, 28–32, 62], and uncertain process [58–60].

In practice, supply-chain operations are subject to increasing uncertainty such as climate change, market fluctuation, manufacturing equipment, and traffic conditions. These uncertainties make business decision making difficult, leading to overproduction and increased inventory costs. In this case, reasonable control of the production inventory in the supply chain can significantly reduce costs and improve the operational efficiency of the supply chain. Due to the rapidly changing market environment, many statistics are not available in a timely manner. Therefore, in an uncertain environment, how to arrange production and inventory will exert a direct impact on a company’s profits. In this paper, an uncertain production-inventory problem with deteriorating items is investigated. Since the dynamic system is affected by uncertain noises, the parameters of the objective function are not easy to obtain and are difficult to achieve in reality. Meanwhile, policymakers may have different personal preferences as some may be cautious while others may take risks. Therefore, we use an optimistic value-based criterion in the model formulation. Due to the lack of historical data, the probability theory was no longer applicable. Thus, we replace the Wiener process in stochastic perturbation with an uncertain canonical process. To address these uncertainties, an optimistic value-based optimal control model is developed. This kind of model can be applied to a system with uncertain disturbance, and it can also be used to control the production inventory of some tangible products, such as food, medicine and chemicals. The aim of this paper is to obtain the optimality equation. Then, the HJB principle is used to solve the optimality equation. Finally, the optimal production rate and inventory level are discussed.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows. In Sect. 2, the basic concepts of the uncertainty theory are reviewed. Section 3 describes the uncertain optimistic value-based optimal control model, and the optimality equation inspired by uncertainty theory. Meanwhile, the optimal production rate and inventory level we obtained by using the HJB principle will also be discussed. In Sect. 4, the numerical experiments for different cases we performed will be described.

2 Preliminaries of the uncertainty theory

Let Γ be a nonempty set, \(\mathcal{L}\) is a σ-algebra over Γ, and each element Λ in \(\mathcal{L}\) is called an event. A set function \(\mathcal{M}\) from \(\mathcal{L}\) to \([0, 1]\) is called an uncertain measure if it satisfies the normality axiom, duality axiom, subadditivity axiom, and product axiom [35, 37].

The uncertain distribution Φ of an uncertain variable ξ is defined by \(\Phi (x)= \mathcal{M}\{\xi \leq x \}\) for any real number x. The uncertain variables \(\xi _{1},\xi _{2},\ldots , \xi _{m}\) are said to be independent (Liu [37]) if

for any Borel sets \(B_{1},B_{2}, \ldots ,B_{n}\) of real numbers.

The expected value of ξ is defined by \(E[\xi ]=\int _{0}^{+\infty}\mathrm{M}\{\xi \geq \mathrm{r}\}\, \mathrm{dr}-\int _{-\infty}^{0} \mathrm{M}\{\xi \leq \mathrm{r}\}\, \mathrm{dr}\) provided that at least one of the two integrals is finite.

Definition 1

([35])

Let ξ be an uncertain variable, and \(\alpha \in (0,1]\). Then,

is called the α-optimistic value to ξ, and

is called the α-pessimistic value to ξ.

Example 1

An uncertain variable ξ is called normal if it has a normal uncertainty distribution

denoted by \(\mathcal{N}(e,\sigma )\), where e and σ are real numbers with \(\sigma >0\).

Theorem 1

([35])

Assume that ξ is an uncertain variable. We have

-

(a)

if \(\lambda \geq 0\), then \((\lambda \xi )_{\sup}(\alpha )=\lambda \xi _{\sup}(\alpha )\), and \((\lambda \xi )_{\inf}(\alpha )=\lambda \xi _{\inf}(\alpha )\);

-

(b)

if \(\lambda <0\), then \((\lambda \xi )_{\sup}(\alpha )=\lambda \xi _{\inf}(\alpha )\), and \((\lambda \xi )_{\sup}(\alpha )=\lambda \xi _{\sup}(\alpha )\);

-

(c)

\((\xi +\eta )_{\sup}(\alpha )=\xi _{\sup}(\alpha )+\eta _{\sup}(\alpha )\) if ξ and η are independent.

Definition 2

([36])

An uncertain process \(C_{t}\) is said to be a canonical process if

-

(1)

\(C_{0}=0\) and almost all sample paths are Lipschitz continuous;

-

(2)

\(C_{t}\) has stationary and independent increments;

-

(3)

every increment \(C_{s+t}-C_{s}\) is a normal uncertain variable with expected value 0 and variance \(t^{2}\).

\(dX_{t}=f(t,X_{t})\,dt+g(t,X_{t})\,dC_{t}\) is called an uncertain differential equation, where f and g are some given functions, and \(X_{t}\) is an uncertain vector.

3 Optimistic model under uncertain environment

Consider the scenario that a manufacturer produces, sells, and stores a single product. This commodity is perishable when stored and the market demand changes with passing time. Due to the lack of historical data about this commodity, the uncertain canonical process is considered in the model development. Before developing the model, we define the relevant parameters and variables as follows:

The state equation of this model can be described by an uncertain differential equation listed as:

where \(C_{t}\) refers to the sales fluctuation of goods caused by unexpected events in reality, such as wars, rumors, and natural disasters. Assume that all parameters and variables are nonnegative.

For nondeterministic factors, in many cases we consider using an expected value to evaluate. However, in other cases, if the decisionmaker wants to make the goal as close to a predetermined value as possible, then we must consider adopting the optimistic value model. Accordingly, an optimistic-value optimal-control model is conceived.

where \(F=\int _{0}^{T}[-c(u(t)-u_{1})^{2}-h(X(t)-x_{1})^{2}]\,dt+BX_{T}\), and \(F_{\sup}\) denotes the optimistic value of F. \(u_{1}\) and \(x_{1}\) represent the expected production rate and inventory level, respectively. B denotes the salvage value per unit of the inventory at time T and α refers to a given confidence level. All functions are continuous. The aim is to determine the optimal product rate \(u(t)\) under the optimistic value of total cost. First, we have the following theorem about the optimistic value.

Theorem 2

For any \((t,x)\in [0,T)\times R^{n}\), and \(\Delta t>0\) with \(t+\Delta t< T\), it yields

where \(x+\Delta X_{t}=X_{t+\Delta t}\).

Proof

According to the definition of the optimistic value, it yields

where \((t,t+\Delta t)\) and \((t+\Delta t, T)\) represent the interval of the control vector.

Note that

which yields

Both sides of the formula (6) takes supremum on the interval \([t+\Delta t,T]\), which yields

According to the following formula

therefore,

In conclusion, the theorem is proved. □

Theorem 3

Let \(J(t,x)\) be twice differentiable on \([0,T)\times R^{n}\), then we can obtain the optimality equation:

where \(J_{\bullet}(t,x)\) represents the partial derivative of the function \(J(t,x)\). The boundary condition is \(J(T,x)=BX_{t}\).

Proof

We can obtain the following formula by adopting a Taylor-series expansion:

Substituting Eq. (10) into Eq. (3), yields

According to Eq. (1), it yields

Substituting Eq. (12) into Eq. (11), yields

Let \(A=J_{x}(t,x)+J_{xx}(t,x)[u(t)-D(t)-\theta X(t)]\Delta t+J_{tx}(t,x) \Delta t\), \(C=\frac{1}{2}J_{xx}(t,x)\), \(\xi =\beta \Delta C_{t}\). The key to Eq. (13) is to solve \([A \xi +C\xi ^{2} ]_{\sup}(\alpha )\).

According to the Theorem 4 in [48], it yields:

If \(C>0\),

where σ denotes the variance of the normal uncertain variable ξ.

If \(C<0\),

If \(C=0\),

Without loss of generality, we discuss Eq. (13) when \(C>0\).

According to Eq. (13) and Eq. (14), it yields

Therefore, we have

We have \(\varepsilon \rightarrow 0\) when \(\Delta t\rightarrow 0\), it yields

Similarly, we can obtain

In conclusion, the theorem is proved. □

Since Eq. (9) is actually a partial differential equation, the HJB principle is used to solve this problem.

Assume that \(J(t,x)\) denotes that the total cost from time t to the end. \(X(t)=x\). Take the partial derivative of both sides of Eq. (9) with respect to u and set it equal to zero, yielding

It follows that

Substituting Eq. (22) into Eq. (9), yields

Note that this is a nonlinear partial differential equation, assuming its solution is

Substituting Eq. (24) into Eq. (23), yields

The formula (25) is a hierarchic system of equations. According to the terminal conditions: \(Q(T)=0\), \(R(T)=B\), \(M(T)=0\), the solution of the system can be obtained:

where \(C_{1}\) and \(C_{2}\) are solved by the terminal conditions \(R(T)=B\), \(M(T)=0\).

Substituting Eq. (26) into Eq. (22), we have the optimal production rate

The optimistic value of the inventory level is:

4 A suitable real example

In this section, we illustrate the effectiveness of modeling through a practical example. Assume that the demand rate \(D(t)\) is a constant equal to the expected production rate \(u_{1}=30\). \(x_{0}=x_{1}=20\), \(c=h=1\), \(\alpha =0.9\), \(\beta =0.05\), \(\theta =0.1\), \(T=2\), \(B=300\). According to Eq. (26), it yields

According to terminal conditions: \(Q(2)=0\), \(R(2)=B=300\), \(M(2)=0\), we have \(C_{1}=\frac{380}{e^{0.2}}\), \(C_{2}=44\text{,}202\). Substituting Eq. (29) into Eq. (22), we have the optimal production rate

Then, we have the optimistic value of the inventory level:

It is obvious that the production rate and the inventory level would increase the functions of confidence level α. When \(\alpha =0.8\), \(\ln\frac{1-\alpha}{\alpha}=\ln\frac{1}{4}>\ln\frac{1}{9}\), and it yields that \(u_{(\alpha =0.9)}>u_{(\alpha =0.8)}\) and \(x_{\sup}(0.9)>x_{\sup}(0.8)\). That is to say, when policymakers are relatively optimistic about the market based on their past experience, the production rate and the inventory level will be higher.

5 Numerical experiment

To verify the feasibility of the proposed uncertain optimistic value model, numerical experiments are conducted in the present section. The demand function is used to express the relationship between the demand quantity of a commodity and various factors that affect the demand quantity. That is, various factors that affect the quantity demand are used as the independent variables, and the quantity demanded is the dependent variable. Following [39], we study the solution of the model under different demand-rate functions. \(B=25\).

-

1.

\(D(t)=30\) (constant). The parameters in the model are set out in Table 1.

Table 1 Parameters in the optimistic value model -

2.

\(D(t)=30+t\) (linear function). The parameters in the model are set out in Table 2.

Table 2 Parameters in the optimistic value model -

3.

\(D(t)=30+0.2t+0.01 t^{2}\) (quadratic function). The parameters in the model are set out in Table 3.

Table 3 Parameters in the optimistic value model -

4.

\(D(t)=e^{(t-T)}\) (exponential function). The parameters in the model are set out in Table 4.

Table 4 Parameters in the optimistic value model

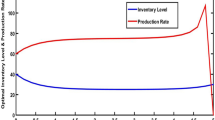

The numerical results are reported in Figs. 1–4. The results suggest that the optimal inventory level and production rate can finally reach their respective target values. Furthermore, when the demand function is a quadratic function or an exponential function, the optimal production rate does not decrease significantly when it is approaching the target value, and it is basically in a state of monotonous increase during this process.

6 Conclusions

In this paper, an uncertain production-inventory problem with deteriorating items was studied. To achieve more accurate decision making in a complex modern societal environment, many uncertainty factors were considered. The uncertain disturbance was expressed as an uncertain canonical process. To study the effects of the uncertain canonical process on the problem, an optimistic value-based optimal control model was proposed. According to the uncertainty theory, the optimality principle and the optimality equation were obtained. A nonlinear partial differential equation was derived by the Hamilton–Jacobi–Bellman principle. The partial differential equation was solved by assuming a specific form of solution and substituting it in an inverse manner. Then, the optimal production rate and inventory level were obtained. Numerical experiments illustrated the effectiveness of the model and the method we adopted under different demand functions.

Future studies are recommended to focus on more complex production and inventory problems, such as cash discount, government intervention, green level, exhaust emission, and pollution-control investment, etc. Some more complex random or uncertain interference factors should also be considered, such as machine breakdown, random defects, human operation error, and warehouse fire, etc. In addition, different modeling methods could also be considered, such as opportunity optimization, critical-value optimization, and robust optimization, etc.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Alshamrani, A., El-Gohary, A.: Optimal control of a two-item inventory system with different types of item deterioration. Econ. Qual. Control 26(2), 201–213 (2011)

Azoury, K., Miyaoka, J.: Optimal and simple approximate solutions to a production-inventory system with stochastic and deterministic demand. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 286(1), 178–189 (2020)

Benhadid, Y., Tadj, L., Bounkhel, M.: Optimal control of production inventory systems with deteriorating items and dynamic costs. Appl. Math. E-Notes 8, 194–202 (2008)

Chen, L., Peng, J., Liu, Z., Zhao, R.: Pricing and effort decisions for a supply chain with uncertain information. Int. J. Prod. Res. 55(1), 264–284 (2017)

Chen, L., Peng, J., Zhang, B., Rosyida, I.: Diversified models for portfolio selection based on uncertain semivariance. Int. J. Syst. Sci. 48(3), 637–648 (2017)

Chen, Y., Zhu, Y.: Optimistic value model of indefinite LQ optimal control for discrete-time uncertain systems. Asian J. Control 20(1), 495–510 (2018)

Chen, Y., Zhu, Y.: Indefinite LQ optimal control with process state inequality constraints for discrete-time uncertain systems. J. Ind. Manag. Optim. 14(3), 913–930 (2018)

Das, D., Kar, M.B., Roy, A., Kar, S.: Two-warehouse production model for deteriorating inventory items with stock-dependent demand under inflation over a random planning horizon. Cent. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 20, 251–280 (2012)

Das, D., Roy, A., Kar, S.: Improving production policy for a deteriorating item under permissible delay in payments with stock-dependent demand rate. Comput. Math. Appl. 60, 1973–1985 (2010)

Das, D., Roy, A., Kar, S.: A volume flexible economic production lot-sizing problem with imperfect quality and random machine failure in fuzzy-stochastic environment. Comput. Math. Appl. 61, 2388–2400 (2011)

Deng, L., You, Z., Chen, Y.: Optimistic value model of multidimensional uncertain optimal control with jump. Eur. J. Control 39, 1–7 (2018)

Deng, L., Zhu, Y.: Optimal control of uncertain systems with jump under optimistic value criterion. Eur. J. Control 38, 7–15 (2017)

Dizbin, N., Tan, B.: Optimal control of production-inventory systems with correlated demand inter-arrival and processing times. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 228, 107692 (2020)

Dobos, I.: Optimal production-inventory strategies for a HMMS-type reverse logistics system. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 81–82, 351–360 (2003)

Dobos, I., Kistner, K.P.: Optimal production-inventory strategies for a reverse logistics system. In: Optimization, Dynamics, and Economic Analysis, pp. 246–258 (2000)

Gao, R.: Stability in mean for uncertain differential equation with jumps. Appl. Math. Comput. 346, 15–22 (2019)

Gao, R.: Stability of solution for uncertain wave equation. Appl. Math. Comput. 356, 469–478 (2019)

Gao, Y., Wen, M., Ding, S.: (s,S) Policy for uncertain single period inventory problem. Int. J. Uncertain. Fuzziness Knowl.-Based Syst. 21(6), 945–953 (2013)

Gayon, J., Vercraene, S., Flapper, S.P.: Optimal control of a production-inventory system with product returns and two disposal options. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 262, 499–508 (2017)

Hedjar, R., Bounkhel, M., Tadj, L.: Self-tuning optimal control of periodic-review production inventory systems with deteriorating items. Adv. Model. Optim. 9(1), 91–104 (2007)

Jia, L., Lio, W., Yang, X.: Numerical method for solving uncertain spring vibration equation. Appl. Math. Comput. 337, 428–441 (2018)

Jia, L., Sheng, Y.: Stability in distribution for uncertain delay differential equation. Appl. Math. Comput. 343, 49–56 (2019)

Ke, H., Huang, H., Gao, X.: Pricing decision problem in dual-channel supply chain based on experts’ belief degrees. Soft Comput. 22(17), 5683–5698 (2018)

Ke, H., Liu, H., Tian, G.: An uncertain random programming model for project scheduling problem. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 30(1), 66–79 (2015)

Ke, H., Liu, J.: Dual-channel supply chain competition with channel preference and sales effort under uncertain environment. J. Ambient Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 8(8), 781–795 (2017)

Ke, H., Wu, Y., Huang, H.: Competitive pricing and remanufacturing problem in an uncertain closed-loop supply chain with risk-sensitive retailers. Asia-Pac. J. Oper. Res. 35(1), 1–21 (2018)

Khmelnitsky, E., Gerchak, Y.: Optimal control approach to production systems with inventory-level-dependent demand. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 47(2), 289–292 (2002)

Li, B., Sun, Y., Aw, G., Teo, K.: Uncertain portfolio optimization problem under a minimax risk measure. Appl. Math. Model. 76, 274–281 (2019)

Li, B., Zhu, Y.: Parametric optimal control of uncertain systems under an optimistic value criterion. Eng. Optim. 50(1), 55–69 (2018)

Li, B., Zhu, Y.: The piecewise parametric optimal control of uncertain linear quadratic models. Int. J. Syst. Sci. 50(5), 961–969 (2019)

Li, B., Zhu, Y., Sun, Y., Aw, G., Teo, K.: Deterministic conversion of uncertain manpower planning optimization problem. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 26(5), 2748–2757 (2018)

Li, B., Zhu, Y., Sun, Y., Aw, G., Teo, K.: Multi-period portfolio selection problem under uncertain environment with bankruptcy constraint. Appl. Math. Model. 56, 539–550 (2018)

Li, S.: Optimal control of production-maintenance system with deteriorating items, emission tax and pollution R&D investment. Int. J. Prod. Res. 52(6), 1787–1807 (2014)

Li, S.: Optimal control of the production-inventory system with deteriorating items and tradable emission permits. Int. J. Syst. Sci. 45(11), 2390–2401 (2014)

Liu, B.: Uncertainty Theory, 2nd edn. Springer, Berlin (2007)

Liu, B.: Fuzzy process, hybrid process and uncertain process. J. Uncertain Syst. 2, 3–16 (2008)

Liu, B.: Some research problems in uncertainty theory. J. Uncertain Syst. 3(1), 3–10 (2009)

Liu, B.: Uncertainty Theory: A Branch of Mathematics for Modeling Human Uncertainty. Springer, Berlin (2010)

Pan, X., Li, S.: Optimal control of a stochastic production-inventory system under deteriorating items and environmental constraints. Int. J. Prod. Res. 53(2), 607–628 (2015)

Qin, Z., Kar, S.: Single-period inventory problem under uncertain environment. Appl. Math. Comput. 219(18), 9630–9638 (2013)

Roul, J., Maity, K., Kar, S., Maiti, M.: Multi-item reliability dependent imperfect production inventory optimal control models with dynamic demand under uncertain resource constraint. Int. J. Prod. Res. 53(16), 4993–5016 (2015)

Shen, J.: An uncertain parallel machine problem with deterioration and learning effect. Comput. Appl. Math. 38, 3 (2019)

Shen, J., Zhu, K.: An uncertain single machine scheduling problem with periodic maintenance. Knowl.-Based Syst. 144, 32–41 (2018)

Shen, J., Zhu, Y.: Chance-constrained model for uncertain job shop scheduling problem. Soft Comput. 20(6), 2383–2391 (2016)

Shen, J., Zhu, Y.: Uncertain flexible flow shop scheduling problem subject to breakdowns. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 32, 207–214 (2017)

Shen, J., Zhu, Y.: An uncertain programming model for single machine scheduling problem with batch delivery. J. Ind. Manag. Optim. 15(2), 577–593 (2019)

Shen, J., Zhu, Y.: A parallel-machine scheduling problem with periodic maintenance under uncertainty. J. Ambient Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 10, 3171–3179 (2019)

Sheng, L., Zhu, Y.: Optimistic value model of uncertain optimal contrl. Int. J. Uncertain. Fuzziness Knowl.-Based Syst. 21(1), 75–87 (2013)

Sheng, Y., Shi, G.: Stability in mean of multi-dimensional uncertain differential equation. Appl. Math. Comput. 353, 178–188 (2019)

Tadj, L., Bounkhel, M., Benhadid, Y.: Optimal control of a production inventory system with deteriorating items. Int. J. Syst. Sci. 37(15), 1111–1121 (2006)

Wang, D., Qin, Z., Kar, S.: A novel single-period inventory problem with uncertain random demand and its application. Appl. Math. Comput. 269, 133–145 (2015)

Wang, K., Yang, Q.: Hierarchical facility location for the reverse logistics network design under uncertainty. J. Uncertain Syst. 8(4), 255–270 (2014)

Wang, X., Ning, Y., Peng, Z.: Some results about uncertain differential equations with time-dependent delay. Appl. Math. Comput. 366, Article ID 124747 (2020)

Wen, M., Qin, Z., Kang, R.: The α-cost minimization model for capacitated facility location-allocation problem with uncertain demands. Fuzzy Optim. Decis. Mak. 13(3), 345–356 (2014)

Yang, H.: Two-warehouse inventory models for deteriorating items with shortages under inflation. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 157, 344–356 (2004)

Yao, K.: Uncertain differential equation with jumps. Soft Comput. 19(7), 2063–2069 (2015)

Yao, K., Ke, H., Sheng, Y.: Stability in mean for uncertain differential equation. Fuzzy Optim. Decis. Mak. 14(3), 365–379 (2015)

Yao, K., Zhou, J.: Uncertain random renewal reward process with application to block replacement policy. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 24(6), 1637–1647 (2016)

Yao, K., Zhou, J.: Ruin time of uncertain insurance risk process. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 26(1), 19–28 (2018)

Yao, K., Zhou, J.: Renewal reward process with uncertain interarrival times and random rewards. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 26(3), 1757–1762 (2018)

Zhang, B., Li, H., Li, S., Peng, J.: Sustainable multi-depot emergency facilities location-routing problem with uncertain information. Appl. Math. Comput. 333, 506–520 (2018)

Zhu, Y.: Uncertain optimal control with application to a portfolio selection model. Cybern. Syst. Int. J. 41(7), 535–547 (2010)

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the Research Foundation of NIIT (YK18-10-02, YK18-10-03).

Funding

No funding was received.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JS and YJ conceived the idea; BL conducted the analyses; ZL and XC provided the data; all authors contributed to the writing and revisions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shen, J., Jin, Y., Liu, B. et al. An uncertain production-inventory problem with deteriorating items. Adv Cont Discr Mod 2022, 42 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-022-03714-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-022-03714-8