Abstract

Background

Dura-attached supratentorial extra-axial ependymoma is a very rare type of tumor, with only nine reported cases. Preoperative diagnosis of dura-attached supratentorial extra-axial ependymoma is difficult and often radiologically misdiagnosed as a meningioma. We report a case of dura-attached supratentorial extra-axial ependymoma that was misdiagnosed using intraoperative histological and cytological examinations.

Case presentation

A 26-year-old Japanese man with headache and nausea was referred to our medical facility. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed a cystic mass of 70 × 53 × 57 mm in the left temporoparietal lobe. A peritumoral band with hyperintensity on T2-weighted imaging was observed at the periphery of the lesion, suggesting an extra-axial lesion with no apparent connection to the ventricle. A dural tail sign was also noted on the gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted image. Preoperative clinical diagnosis was meningioma. Proliferated tumor cells in sheets with intermingled branching vessels were observed in the frozen tissue. Perivascular rosettes were inconspicuous, and the tumor cells had rhabdoid cytoplasm. The tumor was intraoperatively diagnosed as a meningioma, suspected to be a rhabdoid meningioma. Perivascular rosettes were evident in the formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues, suggesting ependymoma. The tumor cells had eosinophilic cytoplasm without a rhabdoid appearance. Anaplastic features, such as high tumor cellularity, increased mitotic activity, microvascular proliferation, and necrosis, were observed. Ependymal differentiation was confirmed on the basis of ultrastructural analysis. Molecular analysis detected C11orf95-RELA fusion gene. The final diagnosis was RELA fusion-positive ependymoma, World Health Organization grade III.

Conclusion

Owing to its unusual location, dura-attached supratentorial extra-axial ependymomas are frequently misdiagnosed as meningiomas. Neuropathologists should take great precaution in intraoperatively diagnosing this rare subtype of ependymoma to avoid misdiagnosis of the lesion as other common dura-attached tumors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Ependymoma is a glial tumor in the central nervous system and corresponds to World Health Organization (WHO) grade II category [1]. Anaplastic ependymoma is histologically a higher-grade tumor than classic ependymoma, corresponding to WHO grade III category, characterized by features such as a high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic (N/C) ratio, elevated mitotic counts, high cell density, widespread microvascular proliferation, and necrosis [2]. However, a definite association between histological grade and biological behavior/survival of ependymomas has not been established [1, 2].

Molecular classification of tumor has been proposed as a prognostic tool for ependymal tumors [3]. Poor prognosis is mainly associated with supratentorial classic/anaplastic ependymomas with RELA fusion gene [3]. RELA fusion-positive ependymomas have become a distinct entity in the classification of ependymal tumors since 2006 [4], and are now classified as grade II or III, depending on histopathological anaplastic features. Recent studies have shown that L1CAM immunohistochemistry can be an alternative for RELA fusion gene detection [5].

Ependymomas usually arise in or near the ventricular system [1]. Intracranial extra-axial ependymoma is a rare tumor, and to date, only 27 cases have been reported. Among them, 21 were confirmed as supratentorial extra-axial ependymomas (SEAEs), 9 of which were reported as SEAE attached to the dura mater (Table 1) [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. Dura-attached SEAEs are often preoperatively misdiagnosed as meningiomas on the basis of radiological findings (Table 1).

Here, we present a case of dura-attached SEAE that was initially misdiagnosed as meningioma on the basis of intraoperative histological and cytological findings. Postoperative evaluation of the paraffin-embedded specimens confirmed this case as an anaplastic ependymoma with dural invasion. Ultrastructural analysis supported the ependymal differentiation of tumor cells, and molecular assays detected C11orf95-RELA fusion gene.

Case presentation

A 26-year-old Japanese male presented with severe headache and nausea for approximately 3 weeks. He had a prior episode of suspected convulsion of which magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a cystic nodular lesion measuring approximately 60 mm in diameter, located in the left parietal lobe of the cerebrum. The patient was administered medication, and symptoms were subsequently relieved. However, 12 days later, he experienced worsened symptoms and was transferred and admitted to the emergency department of the University of Miyazaki Hospital.

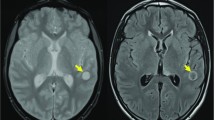

MRI showed a mass of 70 × 53 × 57 mm in the left temporoparietal lobe (Fig. 1a–c). A solid element with slight hypointensity on T1-weighted and hyperintensity on T2-weighted images along the dura mater was noted. Cystic changes were likely associated with the sanguineous fluid. A peritumoral band with hyperintensity on T2-weighted image was observed at the periphery of the lesion, suggesting an extra-axial lesion (Fig. 1b). A dural tail sign was also noted on the gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted image (Fig. 1c). The lesion appeared to be focally infiltrative to the brain surface, but no apparent connection to the ventricle was observed (Fig. 1a–c). Preoperative clinical diagnosis was meningioma, but hemangiopericytoma and ependymoma were included as differential diagnoses. Left parietotemporal craniotomy was performed. The tumor was an extra-axial mass and had partially infiltrated the dura mater and surface of the brain parenchyma in the left temporal lobe. Small pieces of tumor tissue were removed for intraoperative diagnosis. Under an emergency setting, near-total resection was achieved even if the lesion was in the eloquent area. The patient received postoperative adjuvant radiotherapy (total dose 54 Gy). However, within 1 year postsurgery, the tumor recurred and a second resection surgery was performed. Four years after the first surgery, the tumor metastasized to the spinal cord and the patient eventually died (total postoperative follow-up period was 4 years and 4 months).

Magnetic resonance imaging, intraoperative histological and cytological findings of the dura-attached supratentorial extra-axial tumor. a–c Magnetic resonance imaging findings at admission. An axial T1-weighted image showing a cystic mass on left parietal to temporal lobe with hypo- to iso-intensity (a). An axial T2-weighted image (b) and gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted image (c) showing a heterogeneously hyperintense mass with perifocal edema at the periphery (arrowhead in b) and sanguineous material in the cystic spaces. Hyperintense peritumoral band (b) and dural tail sign (c) are indicated by arrows, suggesting a dura-based extra-axial lesion. d–f, Intraoperative histological images showing sheet-like proliferation of tumor cells with branching capillary blood vessels (d), no apparent fine fibrillary processes in the perivascular anucleate zone (e a higher magnification of the blood vessel labeled with an asterisk in d), and rhabdoid cytoplasm in tumor cells (f). g, h, Low-magnification (g) and high-magnification (h) images of an intraoperative cytological specimen. Tumor cells proliferated in irregular clusters close to or distant from blood vessels (g squashed specimen). The tumor cells have hyperchromatic nuclei and eosinophilic cytoplasm with fibrillary processes (h imprinted specimen). Mitosis is also seen (inset in h, squashed specimen). Intraoperative specimens were stained using HE (d–h). Bars: 2 cm in a–c, 100 µm in d, 25 µm in e–h, 50 µm in g, and 12.5 µm in the inset in h

Intraoperative histological/cytological findings

Intraoperative histological specimens were immersed in optimal cutting temperature compound (YUAIKASEI, Japan), fixed in liquid nitrogen, and cryosectioned. Intraoperative cytological specimens were either squashed or imprinted and immediately fixed in 95% ethanol prior to hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining.

Histological findings of the frozen tumor tissue revealed sheet-like proliferation of tumor cells with branching blood vessels (Fig. 1d). Perivascular rosettes were ambiguous, with no apparent fine fibrillary processes in the perivascular anucleate zones (Fig. 1e). Tumor cells exhibited enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei and condensed eosinophilic cytoplasm, giving a rhabdoid appearance (Fig. 1f). In cytological specimens, irregular clusters of tumor cells were observed in the perivascular and nonperivascular areas (Fig. 1g). The tumor cells had oval hyperchromatic nuclei and uniform eosinophilic cytoplasm with fibrillary processes (Fig. 1h). Mitotic cells were observed (Fig. 1h, inset). Whorl formation or intranuclear cytoplasmic pseudo-inclusions were not evident. Additionally, no apparent microvascular proliferation or necrosis was observed. The lesion was intraoperatively diagnosed as a meningioma, suspected to be a rhabdoid meningioma.

Histological and immunohistochemical findings for formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues

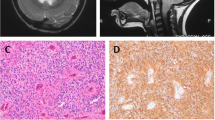

In FFPE tissues, high cellularity was observed, with evidence of tumor cell proliferation and branching vessels (Fig. 2a). Perivascular rosettes were present (Fig. 2a), with distinct fine fibrillary processes in the perivascular anucleate zones (Fig. 2b). The tumor cells exhibited oval hyperchromatic nuclei and eosinophilic cytoplasm with a high N/C ratio (Fig. 2b, c), inconspicuous rhabdoid appearance in the cytoplasm, and high mitotic rates (36 mitotic counts per ten high-power fields) (Fig. 2c). Microvascular proliferation (Fig. 2d), necrosis (Fig. 2e), and dural invasion (Fig. 2f) were observed.

Histological, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural findings of the dura-attached supratentorial extra-axial tumor. a–f, Low-magnification (a and d–f) and high-magnification (b, c) images of the formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded specimen stained using HE showing scattered perivascular rosettes (a), prominent fine fibrillary processes in a perivascular anucleate zone (b), mitotic cells indicated by arrows (c), microvascular proliferation (d), necrosis (e), and tumor invasion to dura marked by D (f). g, h, Immunohistochemical images with paranuclear dot-like positivity for epithelial membrane antigen (g) and membranous positivity for L1 cell adhesion molecule (h). i Transmission electron micrograph (uranyl acetate–lead citrate staining) exhibiting microvilli marked by Mv in microlumen suggesting ependymal differentiation. Bars: 100 µm in a and f, 25 µm in b and g, h, 12.5 µm in c, 50 µm in d, e, and 4 µm in i

Immunohistochemistry was performed as previously reported [14]. The tumor cells were positive for GFAP, EMA (Fig. 2g), and L1CAM (Fig. 2h). The Ki-67 labeling index was 43% (215/500). Collectively, the lesion was histologically confirmed as an anaplastic ependymoma. Details of the primary antibodies used for the immunohistochemistry are provided in Table 2.

Ultrastructural findings

Molecular findings

To detect RELA fusion gene, DNA was extracted from five FFPE sections of 5 μm thickness using a blackPREP FFPE DNA kit (Analitik Jena AG, Jena, Germany) [15]. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and DNA sequencing assays were performed, and C11orf95-RELA fusion gene was detected (Fig. 3a, b).

The final pathological diagnosis was RELA fusion-positive ependymoma, WHO grade III.

Discussion

We report a case of intraoperatively misdiagnosed rare dura-attached SEAE. The tumor was confirmed as anaplastic ependymoma with dural invasion on the basis of the evaluation of the postoperative histological diagnosis of FFPE specimens. A similar case was reported by Salunke et al. [9] as the intraoperative diagnosis “meningioma, favor” (Table 1). However, details about the intraoperative findings were not provided.

An accurate intraoperative diagnosis for dura-attached SEAEs is often challenging, owing to bias by the preoperative information, insufficient time, and lacking ancillary techniques. In our case, to minimize the effect of freezing/drying artifacts during intraoperative diagnosis [16], tissue was snap-fixed in liquid nitrogen. Nevertheless, perivascular rosettes were inconspicuous owing to obscure fine fibrillary processes in the anucleate zones in the intraoperative frozen sections. In the FFPE tissue, perivascular rosettes were evident, and the tumor cells demonstrated eosinophilic cytoplasm without rhabdoid appearance. Electron microscopic examination revealed no apparent whorled bundles of intermediate filaments, usually seen in rhabdoid meningiomas.

RELA fusion-positive ependymoma is considered the worst prognosis category of the three molecular subgroups of supratentorial ependymoma [3]. However, a few studies have reported favorable outcomes in patients diagnosed with RELA fusion-positive ependymoma and who had undergone with gross total resection [17, 18]. C11orf95-RELA fusion gene was previously reported in one SEAE case with a history of 6-month follow-up and no recurrence [10]. The present case with the same fusion gene detected had two recurrences during the postoperative follow-up period of 1 and 4 years, and the patient died 4 months after the second recurrence. Therefore, the biological significance of the RELA fusion gene as a prognostic factor remains ambiguous in supratentorial ependymoma.

Conclusion

We report a case of dura-attached SEAE misdiagnosed as meningioma on the basis of intraoperative diagnosis using frozen tissue sections and cytology. Neuropathologists should take great precaution in intraoperatively diagnosing this rare subtype of ependymoma to avoid misdiagnosis of the lesion as other common dura-attached tumors.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- RELA :

-

V-rel avian reticuloendotheliosis viral oncogene homolog A

- SEAE:

-

Supratentorial extra-axial ependymoma

- C11orf95 :

-

Chromosome 11 open reading frame 95

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- N/C:

-

Nuclear-to-cytoplasmic

- L1CAM:

-

L1 cell adhesion molecule

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- Gy:

-

Gray

- HE:

-

Hematoxylin and eosin

- FFPE:

-

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded

- GFAP:

-

Glial fibrillary acidic protein

- EMA:

-

Epithelial membrane antigen

References

Ellison DW, McLendon R, Wiestler OD, et al. Ependymoma. In: Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK, editors., et al., WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system, revised. 4th ed. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2016. p. 106–11.

Ellison DW, McLendon R, Wiestler OD, et al. Anaplastic ependymoma. In: Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK, editors., et al., WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system, revised. 4th ed. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2016. p. 113–4.

Pajtler KW, Witt H, Sill M, et al. Molecular classification of ependymal tumors across all CNS compartments, histopathological grades, and age groups. Cancer Cell. 2015;27:728–43.

Ellison DW, Korshunov A, Witt H. Ependymoma, RELA fusion-positive. In: Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK, editors. WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system, revised. 4th ed. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2016. p. 112.

Gessi M, Giagnacovo M, Modena P, et al. Role of immunohistochemistry in the identification of supratentorial C11orf95-RELA fused ependymoma in routine neuropathology. Am J Surg Pathol. 2019;43:56–63.

Hanchey RE, Stears JC, Lehman RA, Norenberg MD. Interhemispheric ependymoma mimicking falx meningioma. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1976;45:108–12.

Hayashi K, Tamura M, Shimozuru T, et al. Extra-axial ependymoma—case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 1994;34:295–9.

Youkilis AS, Park P, McKeever PE, Chandler WF. Parasagittal ependymoma resembling falcine meningioma. Am J Neuroradiol. 2001;22:1105–8.

Salunke P, Kovai P, Sura S, Gupta K. Extra-axial ependymoma mimicking a parasagittal meningioma. J Clin Neurosci. 2011;18:418–20.

Nambirajan A, Malgulwar PB, Sharma MC, et al. C11orf95-RELA fusion present in a primary intracranial extra-axial ependymoma: report of a case with literature review. Neuropathology. 2016;36:490–5.

Yang Y, Tian KB, Hao SY, Wu Z, Li D, Zhang JT. Primary intracranial extra-axial anaplastic ependymomas. World Neurosurg. 2016;90:704.e1-704.e9.

Satyarthee GD, Moscote-Salazar LR. Extra-axial giant falcine ependymoma with ultra-rapid growth in child: uncommon entity with literature review. J Pediatr Neurosci. 2016;11:324–7.

Karthigeyan M, Singhal P, Salunke P, Gupta K. A missed differential in an extra-axial lesion with calvarial involvement. Ann Neurosci. 2018;24:207–11.

Akaki M, Ishihara A, Nagai K, et al. Signet ring cell differentiation in salivary duct carcinoma with rhabdoid features: report of three cases and literature review. Head Neck Pathol. 2021;15:341–51.

Fukushima T, Ueda T, Hirato J, Kataoka H. RELA fusion-positive ependymoma accompanied by extensive desmoplasia: a case report. Brain Tumor Pathol. 2020;37:159–64.

Taxy JB. Frozen section and the surgical pathologist: a point of view. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1135–8.

Lillard JC, Venable GT, Khan NR, et al. Pediatric supratentorial ependymoma: surgical, clinical, and molecular analysis. Neurosurgery. 2019;85:41–9.

Wang Q, Cheng J, Li J, et al. The survival and prognostic factors of supratentorial cortical ependymomas: a retrospective cohort study and literature-based analysis. Front Oncol. 2020;10:1585.

Acknowledgements

We thank Mr. Yoshiteru Goto, Laboratory of Bio-Imaging, Frontier Science Research Center, University of Miyazaki, for preparing the specimen for ultrastructural analysis.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MN designed the study and wrote the manuscript. MN, TF, YS, and HK were involved in histological, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural analyses. TF performed molecular analysis. FM and HT contributed to the clinical side of this study, including sample acquisition and collecting the patient information. HK revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The authors state that consent for publication in print and electronically has been obtained from the patient.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Nagayasu, M.A., Fukushima, T., Matsumoto, F. et al. Supratentorial extra-axial RELA fusion-positive ependymoma misdiagnosed as meningioma by intraoperative histological and cytological examinations: a case report. J Med Case Reports 16, 312 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-022-03555-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-022-03555-9