Abstract

Nocardiosis is a disease that mainly affects immunocompromised patients. Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) are standard of care for asthma. This treatment can induce respiratory infections but no case of bronchiolitis nocardiosis have been described so far. A 58-year-old man, with history of controlled moderate allergic asthma, develop an increased cought in the last two years associated with dyspnea on exertion. Within two months, although ICS were increased to high doses, symptoms worsened due to a severe obstructive ventilatory disorder as revealed by pulmonary function tests (PFT). Small-scale lesions (< 10%) were found on chest computed tomography (CT). A bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) found Nocardia abcessus. After six months of Sulfamethoxazole/Trimethoprim, PFT results improved and chest CT became completely normal. We therefore present the case of a bronchiolitis nocardiosis with several bronchial syndrome and the only immunosuppressive factor found were ICS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Nocardiosis is an infectious disease caused by gram positives bacilli aerobics of the genus Nocardia, an ubiquitous bacteria in the environment. Infected tissues are most often the lung, but also the brain and the skin. Pulmonary nocardiosis occurs most often in patients that are immunocompromised or with severe chronic lung disease. The clinical presentation is a pneumonia persisting after usual treatment. It is a severe infection that requires high-dose of antibiotic, most often by sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim, over several months [1].

Asthma is a common chronic disease and ICS is the standard treatment [2]. The main complication of ICS is respiratory infection [3].

However, ICS are not known to favour nocardiosis in the absence of another associated immunosuppressive factor.

We share with you the case of a moderate asthmatic patient who developed pulmonary nocardiosis with predominant bronchiolitis damage.

Case presentation

We assessed a 58-year-old patient who had been treated for moderate allergic asthma since childhood. His treatment included montelukast, a fixed combination of ICS, and a long-acting β2 agonist (fluticasone-salmeterol 250/50 μg two doses per day) via the Diskus powder inhaler. He also had hypertension treated with enalapril and lercanidipine. He worked as a University teacher and was a non-smoker.

His asthma was controlled without the use of oral corticosteroids (OC) until two years ago. In February 2020, symptoms of bronchitis appeared with a productive cough and exercise induced dyspnea without wheezing. The chest X-ray was normal. His symptoms were not improved by several antibiotic courses (pristinamycin, amoxicillin and amoxicillin/clavulanic acid). Having no signs of obstruction, his general practitioner did not prescribe OC and he was referred to the Grenoble Alpes University hospital. He consulted in pneumology in September 2020. He was noted to have a dyspnea rating of 1 on the Medical Research Council Scale with some ronchi but no gastroesophageal reflux. His PFT's highlighted a moderate non-reversible obstructive ventilatory disorder with a forced expiratory volume in one second on forced vital capacity (FEV1/FCV) ratio at 50%, a FEV1 at 2.9L (72% predicted) and a forced expiratory flow at 25–75% (FEF25-75) at 1.6L (48% predicted). On the biological assessment, the specific anti-aspergillary immunoglobin E (IgE) was less than 0.3 kU/L (Immunocap Phadia), the anti-aspergillary serology by immunoelectrophoresis was weakly positive at 2.82 (ELISA), the total IgE was less than 100 KU/L. Eosinophilic polynuclear blood concentration was 0.1 G/L. CRP was less than 3 mg/L. ICS were therefore increased to high doses.

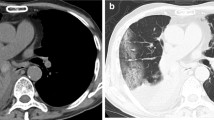

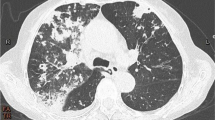

Two months later, the patient felt no improvement of his cough and his dyspnea worsened. FEV1 was at 2.6L (63% predicted) and a FEF25-75 at 1.3 L (38% predicted). On the cardiopulmonary exercise test, he reached a maximal oxygen consumption at 31.2 ml/kg (90% predicted). There was a respiratory limitation with an exhaustion of the ventilatory reserve (9% predicted at peak effort) without desaturation. Cardiovascular adaptation was normal. A chest CT scan revealed foci of basithoracic bronchiolitis adjacent to a right 8 mm juxta-diaphragmatic nodule (Fig. 1A, B). A bronchial fibroscopy were performed and found a normal macroscopic aspect. The cytology of bronchial fluid showed neutrophilic inflammation. The culture of BAL was positive to Nocardia abcessus at 104 CFU/mL.

The interrogation didn’t reveal a particular context of contamination (soil, rotten organic matter and waters). He had no history of invasive bronchial procedures, including fibroscopy at the origin of the potential wound. An immunocompromised assessment was performed. The gammaglobulin level was at 12.7 g/L, HIV serology was negative, the neutrophil count and fasting blood glucose were normal. Lymphocyte immunophenotyping was normal with CD4 + T cell and CD8 + T cell count of 0.99 and 0.51 G/L respectively. Anti-GM-CSF antibodies were negative. The brain CT and skin examination were normal.

Treatment with sulfamethoxazole 800 mg + trimethoprim 160 mg two tablets three times a day was started and ICS were suspended. After three months of antibiotics, the cough and dyspnea decreased without exacerbation of asthma. After six months of treatment, the FEV1 was 3.1L (79% predicted) and the FEF25-75 was stable at 1.1L (32% predicted) (Fig. 2). Chest CT scan had completely normalized.

Discussion and conclusions

ICS treatment is usually prescribed in asthma. In our case, the patient was receiving a medium dose of ICS. A Japanese team reported a case of nocardiosis caused by Nocardia otitidiscaviarum in a 72-year-old patient consuming high dose of fluticasone for asthma [4]. Their patient presented with an acute pneumonia following influenza A infection. The chest CT showed an irregularly shaped solid opacity and a cavitary mass. Pulmonary nocardiosis are most often characterised by acute pneumonitis and pleural effusions with radiological images of lung infiltration and excavated nodules. Cases of pulmonary nocardiosis associated with an ICS treatment have been described in patients without asthma but with a structural lung disease inducing local immunodeficiency: silicosis [5] and COPD [6], but the clinical presentation is that of an acute pneumopathy. In our case report, the infection is chronic, bronchial and the lung parenchyma is preserved. To our knowledge, a nocardiosis bronchiolitis has not been clinically described [7]. However, bronchiolar damage due to a nocardia infection has already been observed on a lung biopsy in context of pneumonia [8].

There is limited data on cases of pulmonary nocardiosis in immunocompetent patients. A case report in 2021 [9] in a 77-year-old non-smoking Japanese patient with no comorbidities found a lung abscess with pleural effusion. There are no other cases in the literature to our knowledge. The need for specific growth medium and longer incubation period of distal lung samples may explain the lack of knowledge about this infection. Nevertheless, this case raises the question of looking for nocardiosis in immunocompetent patients that present a clinical picture of chronic bronchiolitis.

Although ICS is classically considered as a well-tolerated medication, international recommendations insist on the need to lower ICS to the minimum dose to achieve asthma control [2]. Our patient was on moderate-dose ICS while having controlled asthma for 2 years. Therefore, the decrease of ICS doses should always be discussed.

In conclusion, we describe for the first time the case of a nocardia infection with severe bronchiolar damage in a patient whose only immunosuppressive factor was an ICS treatment. His prognosis was favourable after antibiotic treatment. The risk of respiratory infection in a patient treated by ICS should not be overlooked.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on any reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BAL:

-

Bronchoalveolar lavage

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- ICS:

-

Inhaled corticosteroids

- FEF25-75:

-

Forced expiratory flow at 25–75%

- FEV1:

-

Forced expiratory volume in one second

- FVC:

-

Forced vital capacity

- OC:

-

Oral corticosteroids

- PFT:

-

Pulmonary function tests

References

Brown-Elliott BA, et al. Clinical and laboratory features of the Nocardia spp. based on current molecular taxonomy. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19(2):259–82.

Global Initiative for Asthma. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention. www.ginasthma.org.

McKeever T, Harrison T, Hubbard R. Inhaled corticosteroids and the risk of pneumonia in people with asthma: a case control study. Chest. 2003;144(6):1788–94.

Sadamatsu H, et al. Successful treatment of pulmonary nocardiosis with fluoroquinolone in bronchial asthma and bronchiectasis. Respirol Case Rep. 2017;5(3): e00229.

Silva Cruz M, et al. Nocardiosis: when the side effects of therapy mimic symptoms. Cureus. 2022;14(6): e25695.

Martínez Tomás R, et al. Pulmonary nocardiosis: risk factors and outcomes. Respirology. 2007;12(3):394–400.

Burgel PR, et al. Small airways diseases, excluding asthma and COPD: an overview. Eur Respir Rev. 2013;22(128):131–47.

Camp M, Mehta JB, Whitson M. Bronchiolitis obliterans and Nocardia asteroides infection of the lung. Chest. 1987;92(6):1107–8.

Abe S, et al. Case report: pulmonary nocardiosis caused by Nocardia exalbida in an immunocompetent patient. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21(1):776.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the CRISALIS/F-Crin INSERM network (Clinical research Initiative in Severe Asthma: a Lever for Innovation & Science) for the support of some of its members in asthma research. We thank Pr Camille Taillé for proofreading our case report and Laurène Fusi to correct our English grammar.

Funding

No funding was required for the present study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EC, MF, HG wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed in editing the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests in relation to this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Cascarano, E., Frappa, M., Degano, B. et al. Several Nocardia abcessus bronchiolitis in a patient treated with inhaled corticosteroids: a case report. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol 19, 27 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13223-023-00779-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13223-023-00779-2