Abstract

Background

Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) and allergic fungal rhinosinusitis (AFRS) are characterized by hyper-responsiveness of the respiratory tract and the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses, respectively to Aspergillus species and AFRS causes chronic rhinosinusitis. Herein, we report the first case of sinobronchial allergic mycosis (SAM) syndrome, defined as ABPA with concomitant AFRS, caused by Aspergillus fumigatus patient > 80 years.

Case presentation

An 82-year-old male with interstitial pneumonia who returned for follow-up exhibited high-attenuation mucus plug in the right intermediate bronchial trunk, infiltration in the right lung field, and right pleural effusion on regular chest computed tomography (CT). We found unilateral central bronchiectasis in the right upper lobe. Similarly, CT scan of the paranasal sinuses revealed high-attenuation mucus plugs in left ethmoid sinuses. Biopsy specimens from the plugs in the right intermediate bronchial trunk and the left ethmoid sinuses revealed allergic mucin with layers of mucus eosinophils, eosinophil-predominant mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate and Aspergillus hyphae. The patient fulfilled all the major criteria for ABPA and AFRS, and was diagnosed with SAM syndrome. CT scan of the lung and paranasal sinuses revealed apparent amelioration after oral steroid therapy.

Conclusion

Despite mostly reported in relatively young patients, SAM syndrome can occur in elderly individuals as well.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Aspergillus species can cause various allergic diseases, such as allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) and allergic fungal rhinosinusitis (AFRS). Concurrent ABPA and AFRS are defined as sinobronchial allergic mycosis (SAM) syndrome [1]. Because ABPA and AFRS are treated by pulmonologists and otolaryngologists respectively, the condition outside of their expertise and coexistence of ABPA and AFRS can be overlooked. Patients with SAM syndrome in previous reports were relatively young. In Japan, the median patient age at ABPA onset is 57 years, which is older than that reported in other countries [2], raising the possibility of patients with SAM syndrome among the elderly generation in Japan. We herein report the case of an 82-year-old male who simultaneously developed ABPA and AFRS and was diagnosed with SAM syndrome.

Case report

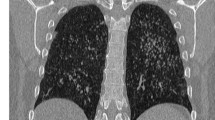

An 82-year-old male was diagnosed with bronchial asthma at 10 years of age and treated with inhalants and he did not receive treatment for asthma since the age of 30 because of the resolution of bronchial asthma. He was followed at our hospital for idiopathic interstitial pneumonia by annual regular chest X-ray and computed tomography (CT) scans for 4 years. The patient’s interstitial pneumonia, with minimal change in radiological findings was stable over the years, he complained no symptoms. He did not indicate exposure to fungus. Chest X-ray and CT scan obtained in December 2017 revealed high-attenuation mucus plug in right intermediate bronchial trunk, right pleural effusion (Fig. 1a), and infiltration in the right lung field (Fig. 1b).

We also found unilateral bronchiectasis in the right upper lobe.

Additionally, a slight fibrotic change along the pleural line reflecting interstitial pneumonia was observed. CT of paranasal sinuses obtained to investigate nasal congestion for 3 years, revealed high-attenuation mucus plug in the left ethmoid sinuses (Fig. 2). Physical examination revealed decreased breath sounds in the right lower lung field. No wheezing and rhonchi were observed on auscultation.

Blood tests showed a total leucocyte count of 9300/mm3 with 8% eosinophils (absolute eosinophil count, 744/mm3) and elevated C-reactive protein. Radioimmunosorbent test revealed elevated IgE levels (1460 IU/ml), and the radioimmunosorbent test for specific IgE antibodies against Aspergillus, Penicillium and Candida were positive. Serum precipitins to Aspergillus were also positive. We confirmed local urticaria and lash 15 min after subcutaneous injection of A. fumigatus antigen and this was positive of immediate cutaneous hypersensitivity reaction. He had a history of right nephrectomy because of renal cancer and did not experience recurrence.

Pulmonary function test showed the following: forced vital capacity (FVC), 1.86 L (55.4% of predicted value); forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1), 1.60 L (64.3% of predicted value); and FEV1/FVC, 86.0%. Bronchoscopy for definite diagnosis confirmed bronze-colored, hard mucus plug in the right intermediate bronchial trunk (Fig. 3a), and pathological examination of multiple biopsy specimens stained by hematoxylin–eosin revealed allergic mucin with layers of mucus, eosinophils, and eosinophil-predominant mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate and Charcot–Leyden crystals (Fig. 4a). Grocott’s stain revealed fungal hyphae with a 45° branch angle within the allergic mucin (Fig. 4b). We performed open biopsy of the ethmoid sinuses and found similar mucus plug there, which revealed similar pathological findings in the right intermediate bronchial trunk (Fig. 3b), including fungal hyphae with a 45° branch angle within allergic mucin (Fig. 4c). Mucus plug cultures were positive for A. fumigatus. The patient met of the diagnostic criteria for ABPA by Rosenberg and Patterson [3] as well as those for AFRS [4], and thus he was diagnosed with SAM syndrome [1].

a Hematoxylin–eosin staining of allergic mucin with layers of mucus, eosinophils, eosinophil-predominant mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate and Charcot–Leyden crystals. Original magnification, ×200. b Grocott’s staining showing fungal hyphae with a 45° branch angle within allergic mucin. Original magnification, ×400. c Grocott’s staining showing fungal hyphae within the maxillary sinus. Original magnification, ×400

The patient was treated with 0.5 mg/kg prednisolone daily for 1 month, which was reduced to 0.35 mg/kg prednisolone daily. His total IgE levels fell to 206 IU/ml after 3 months. CT of the lung and paranasal sinuses showed apparent amelioration (Fig. 5a–c), and nasal congestion was resolved after 3 months steroid therapy. Now, there has been about 1 year and 4 months after the diagnosis, the patient is currently receiving oral steroid therapy (0.1 mg/kg) and remains in good condition with no deteriorations.

Discussion

We herein present an elderly patient with a history of bronchial asthma who was diagnosed with SAM syndrome, based on concomitant ABPA and AFRS. Biopsy specimens from the right intermediate bronchial trunk and the left ethmoid sinuses revealed Aspergillus hyphae with allergic mucin and extensive eosinophilic infiltration. Oral steroid therapy was efficient against both ABPA and AFRS, and the patient remains in good condition.

ABPA is caused by hyper-responsiveness of the respiratory epithelium to A. fumigatus, which was first described in 1952 [5]. In 1977, Rosenberg and Patterson proposed the following diagnostic criteria for ABPA: (1) episodic bronchial obstruction, (2) peripheral eosinophilia, (3) positive immediate skin test to Aspergillus, (4) positive precipitin test to Aspergillus, (5) increased total serum IgE, (6) history of transient or fixed lung infiltrates, and (7) proximal bronchiectasis [3]. The current patient met all these diagnostic criteria and diagnosed with ABPA. Conversely, AFRS is a distinct type of chronic rhinosinusitis that occurs because of immunological reaction to noninvasive fungi present in the sinuses [6] and can be considered as an upper-airway equivalent of ABPA [1]. In 2004, Meltzer et al. [4] proposed the following diagnostic criteria for AFRS: (1) endoscopic evidence of allergic mucin (pathology showing fungal hyphae with degranulating eosinophils) and sinus inflammation, (2) CT or magnetic resonance imaging findings consistent with rhinosinusitis, (3) evidence of fungal sensitization by skin testing or serum IgE, (4) no histologic evidence of invasive disease. The current patient met the diagnostic criteria of AFRS as well.

Concurrence of ABPA and AFRS is increasingly recognized. In one study of 95 patients with ABPA, diagnoses of definite and probable AFRS were reached in 7 (7%) and 13 (14%) patients, respectively [7], although their concurrence might be more frequent based on the “one airway, one disease” hypothesis. Another study reported that AFRS was confirmed in 80% with patients of ABPA [8]. The difference in the percentage of patients with concomitant ABPA and AFRS between the two studies might be partially explained by the differences in the diagnostic criteria for ABPA and AFRS. SAM syndrome might be more frequent than anticipated. As a rationale for the oversight of their concurrence, Agarwal et al. [9] suggested that different specialists treat ABPA and AFRS, and the use of oral glucocorticoids and/or antifungal agents in either disorder might mask the manifestation of the other disorder.

Treatment approaches for ABPA and AFRS differ to some extent. Therefore, recognition of both disease is important. The cornerstone of ABPA management includes initiation of anti-inflammatory therapy (with systemic glucocorticoids) that aims to attenuate immunological hyperactivity. Systemic glucocorticoids are considered as the treatment of choice. Another treatment option is to use antifungal agents, (such as azoles and nebulized amphotericin B) to attenuate fungal burden in the tracheobronchial tree, thereby decreasing the antigen load [9]. Conversely, the first choice of treatment for AFRS is surgical debridement of the sinuses with endoscopic surgery [10]. Surgery is followed by aggressive medical therapy with postoperative glucocorticoids (prednisolone 0.5 mg/kg for 4 weeks, tapered over the next 2–5 months) to achieve a satisfactory long-term outcome [11]. Agarwal et al. [9] reported that concomitant occurrence of the two disorders is associated with worse outcomes. Therefore, diagnosis should be carefully achieved. In the current case, 0.5 mg/kg oral prednisolone was administered after surgery and the CT scans of the lung and paranasal sinuses demonstrated apparent amelioration.

Of note, the current patient was older than the previously reported patients with SAM syndrome. A Japanese nationwide survey determined that the median age at the onset for ABPA with central bronchiectasis was 57 years, which is older than that reported in other countries [2]. The median ages of onset for ABPA with central bronchiectasis were 34 and 36 years in two Indian studies, 41 years in a Chinese study, and 47 years in a British study [12,13,14,15]. We speculate that the onset of SAM syndrome might be later in Japan because of the later onset of ABPA. Moreover, several reports from East Asian countries demonstrate relatively lower total serum IgE levels in patients with ABPA [16,17,18].

It is conceivable that sensitization to A. fumigatus might not decrease with age in asthmatic patients [19]. Tanaka et al. reported that patients with increased IgE over a 10 year period had a higher prevalence of Aspergillus sensitization [20], suggesting that the significance of aspergillosis in asthmatic patients might be increasing with age.

Moreover, it is reported that de novo sensitization to A. fumigatus in adult asthma over a 10-year observation period [21]. In the study, frequencies of patients positive for IgE to A. fumigatus extract increased as the patients get old.

Population aging is a global issue that is estimated to be more rapid in Asian countries. In 2007, more than half of the world’s population was living in cities. Prolonged life expectancy and urbanization are thought to increase asthma in the elderly [22], which is also true for other allergic diseases. Although allergies have been considered a minor concern in the elderly (usually defined as those aged ≥ 65 years), recent epidemiologic studies indicate that allergic diseases are more prevalent than expected in the aged population [23]. Therefore, SAM syndrome should also be considered in aged individuals.

Conclusion

First case report of SAM syndrome in a patient ≥ 80 years highlights the importance of investigation of paranasal sinusitis for potential AFRS before treatment for ABPA because the treatment approaches for the two diseases are different.

Availability of data and materials

Please contact author for data requests.

Abbreviations

- ABPA:

-

allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis

- AFRS:

-

allergic fungal rhinosinusitis

- SAM:

-

sinobronchial allergic mycosis

- CT:

-

computed tomography

- IgE:

-

immunoglobulin E

- FEV1:

-

forced expiratory volume in 1 s

- FVC:

-

forced vital capacity

References

Venarske DL, et al. Sinobronchial allergic mycosis: the SAM syndrome. Chest. 2002;121:1670–6.

Oguma T, et al. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in Japan: a nationwide survey. Allergol Int. 2018;67(1):79–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alit.2017.04.011 (Epub 2017 May 23).

Rosenberg M, et al. Clinical and immunologic criteria for the diagnosis of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Ann Intern Med. 1977;86:405–14.

Meltzer EO, et al. Rhinosinusitis: establishing definitions for clinical research and patient care. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:s155–212.

Hinson KF, et al. Broncho-pulmonary aspergillosis; a review and a report of eight new cases. Thorax. 1952;7(4):317–33.

Chakrabarti A, et al. Fungal rhinosinusitis: a categorization and definitional schema addressing current controversies. Laryngoscope. 2009;119:1809–18.

Shah A, et al. Concomitant allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis and allergic Aspergillus sinusitis: a review of an uncommon association. Clin Exp Allergy. 2001;31:1896–905.

Barac A, et al. Fungi-induced upper and lower respiratory tract allergic diseases: one entity. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:583. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2018.00583 (eCollection 2018).

Agarwal R, et al. Are allergic fungal rhinosinusitis and allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis lifelong conditions? Med Mycol. 2017;55(1):87–95 (Epub 2016 Sep 6).

Gupta AK, Shah N, Kameswaran M, et al. Allergic fungal rhinosinusitis. Clin Rhinol An Int J. 2012;5:72–86.

Callejas CA, Douglas RG. Fungal rhinosinusitis: what every allergist should know. Clin Exp Allergy. 2013;43:835–49.

Ye F, Zhang NF, Zhong NS. Clinical and pathological analysis of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in China. Zhonghua Jie he He Hu Xi Za Zhi. 2009;32:434–8 (in Chinese).

Agarwal R, Gupta D, Aggarwal AN, Behera D, Jindal SK. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis: lessons from 126 patients attending a chest clinic in north India. Chest. 2006;130:442–8.

Chakrabarti A, Sethi S, Raman DSV, Behera D. Eight-year study of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in an Indian teaching hospital. Mycoses. 2002;45:295–9.

Menzies D, Holmes L, McCumesky G, Prys-Picard C, Niven R. Aspergillus sensitization is associated with airflow limitation and bronchiectasis in severe asthma. Eur J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;66:679–85.

Tanimoto H, Fukutomi Y, Yasueda H, Takeuchi Y, Saito A, Watai K, et al. Molecular-based allergy diagnosis of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in Aspergillus fumigatus-sensitized Japanese patients. Clin Exp Allergy. 2015;45:1790–800.

Ishiguro T, Takayanagi N, Uozumi R, Baba Y, Kawate E, Kobayashi Y, et al. Diagnostic criteria that can most accurately differentiate allergic bronchopulmonary mycosis from other eosinophilic lung diseases: a retrospective, single-center study. Respir Invest. 2016;54:264–71.

Kim JH, Jin HJ, Nam YH, Hwang EK, Ye YM, Park HS. Clinical features of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in Korea. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2012;4:305.

Fukutomi Y, Taniguchi M, et al. Sensitization to fungal allergens: resolved and unresolved issues. Allergol Int. 2015;64(4):321–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alit.2015.05.007 (Epub 2015 Jun 9).

Tanaka A, et al. Longitudinal increase in total IgE levels in patients with adult asthma: an association with poor asthma control. Respir Res. 2014;20(15):144. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-014-0144-8.

Water K, et al. De novo sensitization to Aspergillus fumigatus in adult asthma over a 10-year observation period. Allergy. 2018;73(12):2385–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/all.13566 (Epub 2018 Aug 16).

Makino S. Asthma in the elderly and aging societies in Asia Pacific. Asia Pac Allergy. 2012;2(1):1–2. https://doi.org/10.5415/apallergy.2012.2.1.1 (Epub 2012 Jan 31).

Song WJ, et al. Respiratory allergies in the elderly: findings from the Korean Longitudinal Study on Health and Aging phase I study (2005–2006). Asia Pac Allergy. 2017;7(4):185–92. https://doi.org/10.5415/apallergy.2017.7.4.185 (Epub 2017 Oct 30).

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EM wrote the first draft of the manuscript and contributed all revisions of the manuscript and also performed skin test and bronchoscopy. IN performed sinus surgery. SM and NK corrected the manuscript and supervised the investigations. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

The individual described in the above case report has completed and signed a consent form for publication and presentation.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Mochizuki, E., Matsuura, S., Kubota, T. et al. Sinobronchial allergic mycosis syndrome in an elderly male. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol 15, 35 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13223-019-0349-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13223-019-0349-y