Abstract

Background

Critical care saves lives of the young with reversible disease. Little is known about critical care services in low-income countries. In a setting with a shortage of doctors the actions of the nurse bedside are likely to have a major impact on the outcome of critically ill patients with rapidly changing physiology. Identification of severely deranged vital signs and subsequent treatment modifications are the basis of modern routines in critical care, for example goal directed therapy and rapid response teams. This study assesses how often severely deranged vital signs trigger an acute treatment modification on an Intensive Care Unit (ICU) in Tanzania.

Methods

A medical records based, observational study. Vital signs (conscious level, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, heart rate and systolic blood pressure) were collected as repeated point prevalences three times per day in a 1-month period for all adult patients on the ICU. Severely deranged vital signs were identified and treatment modifications within 1 h were noted.

Results

Of 615 vital signs studied, 126 (18%) were severely deranged. An acute treatment modification was in total indicated in 53 situations and was carried out three times (6%) (2/32 for hypotension, 0/8 for tachypnoea, 1/6 for tachycardia, 0/4 for unconsciousness and 0/3 for hypoxia).

Conclusions

This study suggests that severely deranged vital signs are common and infrequently lead to acute treatment modifications on an ICU in a low-income country. There may be potential to improve outcome if nurses are guided to administer acute treatment modifications by using a vital sign directed approach. A prospective study of a vital sign directed therapy protocol is underway.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Global critical care capacity is increasing [1–3]. While low income countries (LIC) have the greatest burden of critical illness, little is known about the state of their critical care services [2, 4–6]. Critical care has previously not been considered a cost-effective part of the health systems of LIC [7]. This may have been due to a perception that critical care invariably involves expensive treatments and equipment, such as in Intensive Care Units (ICUs) in high-income countries (HIC). However, evidence is growing that several aspects of critical care, such as close monitoring by nurses, maintaining a free airway, oxygen therapy, intravenous fluid resuscitation and some acute surgical operations may be cost-effective in LIC, even when compared to preventive care approaches [8–10]. In its potential to save lives of the young and previously healthy with reversible disease, it deserves increased attention from researchers and policy-makers [2, 4, 11, 12].

A fundament of critical care is the recognition of severely deranged physiology and subsequent acute treatment modifications. The patients’ vital signs give useful information about physiological derangement and have been shown to correlate with negative outcomes such as cardiac arrest and death [13–16]. The use of vital signs as triggers for acute treatment modifications is the basis of modern routines in critical care, for example goal directed therapy [17] and rapid response teams [18, 19]. It is not known to what extent ICUs in LICs utilise goal directed therapies or severely deranged vital signs as treatment triggers.

Tanzania is a LIC in East Africa with a population of 44 million. Health expenditure in Tanzania is 27 USD per person per year [20]. Critical Care is in its infancy in Tanzania. Most hospitals do not have an ICU, and of the 820 doctors in Tanzania, only 15 are specialists in critical care [21] (personal communication: Dr U Mpoki, president of the Society of Anaesthesiologists of Tanzania).

This study, the first from the interventional vital signs directed therapy (VSDT) research collaboration, aims to assess how often severely deranged vital signs trigger an acute treatment modification on an ICU in Tanzania.

Methods

An observational, medical records based study from the 6-bedded ICU in Muhimbili National Hospital (MNH) in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

Ethics

Ethical clearance was granted by the National Institute of Medical Research in Tanzania (NIMR/HQ/R.8a/Vol.IX/1606), Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences (MU/DRP/AEC/Vol.XVI/125) and the Ethical Review Board in Stockholm (EPN/2015/673-31/2). Permission for the study was granted by The Tanzanian Commission for Science and Technology and by MNH. As the study was part of quality improvement on the ICU, individual patient consent was not required by the ethical committees.

Setting

Muhimbili National Hospital is a national referral hospital with 900 beds. During the study period 5 anaesthesiologists shared the workload in the hospital, including 24 h medical cover for the 11 operating theatres and the ICU. There were 31 nurses employed on the ICU, of which one had a formal critical care education. There were 4–6 nurses working per shift. All ICU-beds were equipped with respirators and non-invasive monitoring of vital signs. Available par-enteral treatment included crystalloids, blood transfusion, antibiotics and the vasoactive drug Dopamine. The laboratory services took approximately 6 h for standard analyses including arterial blood gases, blood counts and chemistry. Standard X-rays were available but the hospital CT scanner was not functioning. The study was conducted as a part of the Muhimbili–Karolinska Anaesthesia and Intensive Care Collaboration (MKAIC), an international partnership that has been working to investigate and improve care at Muhimbili since 2008.

Data

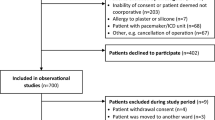

All patients over 16 years admitted to the ICU in a 1 month period were identified and data from that month were included. The patients were identified from the ICU-admission book and their medical notes were retrieved. Handwritten ICU Observation Charts were found within the notes. The ICU Observation Charts contain nurses’ records of vital signs, treatments administered and fluid balances every hour (Figure 1).

Five vital signs were studied: conscious level, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, heart rate and systolic blood pressure. We extracted the vital signs observations as repeated point prevalences (observation-timepoints) every 8 h (08:00, 16:00, 24:00). This interval was chosen as a trade-off to capture most changes in patient condition but avoiding dependency on the most severely ill patients. For some patients, documentation by the nurses had been reduced to 2- or 3-h and in the case of missing data for that reason; values between 1 h earlier and 2 h later were used.

When a severely deranged vital sign was identified we noted whether any treatment modification was carried out within the following hour and whether this treatment modification was appropriate.

The vital signs directed therapy protocol

Severely deranged vital signs and appropriate acute treatment modifications were defined from the vital signs directed therapy (VSDT) protocol (Figure 2). The VSDT protocol is the result of a 2 year international collaborative process between the authors of this study and other experts in the MKAIC collaboration and the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM) group for Global Intensive Care.

VSDT utilises seven vital signs. Vital sign observations are categorized as normal (green), abnormal (yellow) and danger signs (red). The cut-offs for danger signs are based on the Karolinska Hospital Medical Emergency Team (MET) triggers [22] and the ESICM Vital Nursing Card (Unpublished). A danger sign calls for immediate treatment by the nurse. Every vital sign extracted for the study was assigned the corresponding VSDT-colour. At the time of this study, the VSDT protocol was not used in clinical practice.

Data analysis

SPSS (IBM®) was used for descriptive statistics. Due to sample size, statistical inferences were not made. Numerical data are presented as median and interquartile range.

Results

15 adult patients were admitted to the ICU during the study period. Nine were female and the median age was 37 years (28–46). Four patients died in the ICU (25%). Diagnoses are shown in Table 1. Out of 15 patients, 13 medical records were found in the archives. ICU observation charts were found from 9 patients and vital signs data from 126 observation-timepoints. For the patients with ICU observation charts available, a total of nine charts were missing from the notes.

Vital signs

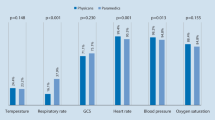

In the 126 observation-timepoints there were data for 615 vital signs, of which 112 were severely deranged (18%) (Figure 3). In 53 of these severely deranged vital signs an acute treatment modification was indicated (9% of all observation-timepoints).

Distribution of vital signs. aRespiratory rate was missing in 15 observation-timepoints. bAn acute treatment modification was indicated in 4 of the 63 observation-timepoints with GCS <9 as the patient had an unprotected airway. In the other 59 observation-timepoints acute treatment modification was not indicated according to VSDT. In these observation-timepoints 58 patients were intubated and one was in the lateral position.

An appropriate treatment modification was done in 3 of these 53 occasions (6%).

-

A.

For conscious level, data was complete. In 63 observation-timepoints a severely deranged vital sign was present (50%). In four of these cases the airway was unprotected. No acute treatment modification to protect the airway or any other action took place in these four cases.

-

B.

Oxygen saturation data was complete and values were in the majority of cases normal. In 31% of cases saturation was 100%, and all of those patients were receiving oxygen therapy. Respiratory rate (RR) was available in 111 observation-timepoints. In none of the cases where severely deranged vital signs for RR (n = 8) or saturation (n = 3) were recorded was the oxygen delivery increased or the position of the patient changed. Nor were changes in ventilator settings made or any other action taken.

-

C.

Heart rate and blood pressure data was complete. Severe hypotension was observed in 32 observation-timepoints (25%). In two cases 500 ml IV fluid was given. In the other 30 cases no acute treatment modification was made. One patient was already receiving low dose-Dopamine infusion, which was not increased when the patient became hypotensive. Six observations of severe tachycardia were found and in one case an appropriate acute treatment modification was made. In that case a bolus of 500 ml iv-fluid was given. In one case with tachycardia and anuria another action was taken; Pethidine was administered.

Discussion

This observational study suggests that severely deranged vital signs occur frequently and rarely trigger acute treatment modifications on an ICU in a LIC. Of all documented vital signs 18% were severely deranged and for 9% an acute treatment modification was indicated. In only 6% of these situations was an appropriate acute treatment modification made.

To our knowledge, this is the first attempt to study the processes of care on an ICU in a LIC. We chose a vital-signs based methodology that provides information about illness severity and care processes that is realistic for the level of resources in healthcare in LICs. The results are striking and suggest an issue that has previously been neglected. The method may be used in larger clinical studies or in needs assessments of specific wards or ICUs.

The study is single centred and the sample size small, so generalising to other ICUs in Tanzania or other LICs is limited. Tracing medical records in hospitals in LICs is notoriously challenging, and we have missing data due to lost patient records and lost ICU observation charts. This missing data may be non-random, however, we believe it is unlikely that the patients with missing records would be much more stable or that their acute medical management would differ substantially from the patients in the study.

We used VSDT-danger signs to define severely deranged vital signs. Other methods could have been used such as MEWS [23], NEWS [24] or SATS [25]. We rejected these because they are more complicated compound scores and, while identifying critical illness, are not designed for translation into treatment suggestions.

We used VSDT-treatments to define the appropriate acute treatment modifications. The VSDT protocol is simple and standardised, and was developed to be practically suited as support for nurses on ICUs in LICs where doctors are scarce. Its simplicity could be problematic, as some deranged vital signs may warrant alternative treatments. We argue, however, that the initial treatment suggestions for airway threat, hypoxia and shock are uncontroversial and that the small minority of patients in which other initial treatment might be preferred would not be possible to identify without a much more advanced monitoring than is reasonable in this setting. Action would be better than no action for the vast majority of patients.

As many as 25% of observations indicated danger for hypoperfusion due to hypotension. In very few cases was appropriate action taken. If the indicated treatment modifications had been carried out, the subsequent increase in the amount of IV fluid boluses implies a potential to avoid organ damage [26]. Although the optimal volumes, types and monitoring methods of fluid therapy are debated, the use of IV fluids in non-cardiac causes of shock is established practice in HIC [27]. It is a cornerstone of the early goal directed therapy for sepsis [17] and in a sepsis bundle that showed markedly beneficial effects on mortality in Uganda [28]. It has recently been challenged in a paediatric population in LIC [29] but remains the global standard of care for adults [8, 30, 31].

Several authors have called for improved basic critical care in LICs [1, 6, 7, 32–34], which is likely to be a cost-effective part of health services [12, 35]. Multiple challenges to delivery of critical care in Tanzania have been identified, which may in part explain the results of this study. As well as the lack of financial and human resources at the national level [20], high lead times delaying treatment both pre- and in-hospital have been described [36]. A lack of routines and training for the identification and treatment of acute illness may be more important than availability of basic drugs and equipment [21, 37]. Fatalism and hierarchical structures may discourage action by the bedside staff [38, 39].

Ongoing initiatives are attempting to improve critical care in resource scarce settings. Guidelines have been written for sepsis management [8] and protocols for sepsis care have been trialled in Zambia [40] and Uganda [28]. A study of computer-programme-supported comprehensive critical care is underway that will also include hospitals in LICs [41].

We believe that improvement efforts should focus on simple, cheap interventions with a potential for marked gains in mortality and morbidity. Interventions that are realistic to implement and sustain in a setting where resources are scarce have a better chance of success. Our findings suggest that outcomes may be improved if severely deranged vital signs are identified and trigger acute treatment responses that can be carried out by the nurse bedside. A successful intervention addressing this need does not necessitate new treatments, diagnostic tools or staff and could be a cost-effective addition to the ordinary care.

Conclusion

This study suggests that severely deranged vital signs are common and infrequently lead to acute treatment modifications in an ICU in a low-income country. A prospective interventional study with before and after-design studying the effect on mortality of the implementation of a vital signs directed protocol (VSDT) is underway. We believe that there is potential for the VSDT protocol to alter clinical practice. This may lead to improved outcomes and reduced mortality.

Change history

02 August 2017

An erratum to this article has been published.

Abbreviations

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- GCS:

-

Glasgow Coma Scale

- HIC:

-

High-income country

- ICU:

-

Intensive Care Unit

- LIC:

-

low-income country

- MEWS:

-

Modified Early Warning Score

- MKAIC:

-

Muhimbili-Karolinska Anaesthesia and Intensive care Collaboration

- MNH:

-

Muhimbili National Hospital

- NEWS:

-

National Early Warning Score

- RR:

-

respiratory rate

- SATS:

-

South African Triage Scale

- USD:

-

United States Dollar

- VSDT:

-

vital signs directed therapy

References

Murthy S, Wunsch H (2012) Clinical review: international comparisons in critical care—lessons learned. Crit Care (London, England) 16:218

Adhikari NK, Fowler RA, Bhagwanjee S, Rubenfeld GD (2010) Critical care and the global burden of critical illness in adults. Lancet 376:1339–1346

Du B, Xi X, Chen D, Peng J (2010) Clinical review: critical care medicine in mainland China. Crit Care (London, England) 14:206

Baker T (2009) Critical care in low-income countries. Trop Med Int Health 14:143–148

Baelani I, Jochberger S, Laimer T, Otieno D, Kabutu J, Wilson I et al (2011) Availability of critical care resources to treat patients with severe sepsis or septic shock in Africa: a self-reported, continent-wide survey of anaesthesia providers. Crit Care (London, England) 15:R10

Kwizera A, Dunser M, Nakibuuka J (2012) National intensive care unit bed capacity and ICU patient characteristics in a low income country. BMC Res Notes 5:475

Riviello ED, Letchford S, Achieng L, Newton MW (2011) Critical care in resource-poor settings: lessons learned and future directions. Crit Care Med 39:860–867

Dunser MW, Festic E, Dondorp A, Kissoon N, Ganbat T, Kwizera A et al (2012) Recommendations for sepsis management in resource-limited settings. Intensive Care Med 38:557–574

McCord C, Chowdhury Q (2003) A cost effective small hospital in Bangladesh: what it can mean for emergency obstetric care. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 81:83–92

Gosselin RA, Thind A, Bellardinelli A (2006) Cost/DALY averted in a small hospital in Sierra Leone: what is the relative contribution of different services? World J Surg 30:505–511

Razzak JA, Kellermann AL (2002) Emergency medical care in developing countries: is it worthwhile? Bull World Health Organ 80:900–905

Firth P, Ttendo S (2012) Intensive care in low-income countries—a critical need. N Engl J Med 367:1974–1976

Kause J, Smith G, Prytherch D, Parr M, Flabouris A, Hillman K (2004) A comparison of antecedents to cardiac arrests, deaths and emergency intensive care admissions in Australia and New Zealand, and the United Kingdom—the ACADEMIA study. Resuscitation 62:275–282

Smith AF, Wood J (1998) Can some in-hospital cardio-respiratory arrests be prevented? A prospective survey. Resuscitation 37:133–137

Rylance J, Baker T, Mushi E, Mashaga D (2009) Use of an early warning score and ability to walk predicts mortality in medical patients admitted to hospitals in Tanzania. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 103:790–794

Buist M, Bernard S, Nguyen TV, Moore G, Anderson J (2004) Association between clinically abnormal observations and subsequent in-hospital mortality: a prospective study. Resuscitation 62:137–141

Rivers E, Nguyen B, Havstad S, Ressler J, Muzzin A, Knoblich B et al (2001) Early goal-directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med 345:1368–1377

Chan PS, Jain R, Nallmothu BK, Berg RA, Sasson C (2010) Rapid response teams: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med 170:18–26

Winters BD, Weaver SJ, Pfoh ER, Yang T, Pham JC, Dy SM (2013) Rapid-response systems as a patient safety strategy: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 158:417–425

WWorld Health Organization (WHO) (2012) World health statistics 2012. WHO, Geneva

Baker T, Lugazia E, Eriksen J, Mwafongo V, Irestedt L, Konrad D (2013) Emergency and critical care services in Tanzania: a survey of ten hospitals. BMC Health Ser Res 13:140

Konrad D, Jaderling G, Bell M, Granath F, Ekbom A, Martling CR (2010) Reducing in-hospital cardiac arrests and hospital mortality by introducing a medical emergency team. Intensive Care Med 36:100–106

Burch VC, Tarr G, Morroni C (2008) Modified early warning score predicts the need for hospital admission and inhospital mortality. Emerg Med J 25:674–678

McGinley A, Pearse RM (2012) A national early warning score for acutely ill patients. BMJ (Clin Res Ed) 345:e5310

Twomey M, Wallis LA, Thompson ML, Myers JE (2012) The South African Triage Scale (adult version) provides reliable acuity ratings. Int Emerg Nurs 20:142–150

Wilms H, Mittal A, Haydock MD, van den Heever M, Devaud M, Windsor JA (2014) A systematic review of goal directed fluid therapy: rating of evidence for goals and monitoring methods. J Crit Care 29:204–209

Marik PE, Desai H (2012) Goal directed fluid therapy. Curr Pharm Des 18:6215–6224

Jacob ST, Banura P, Baeten JM, Moore CC, Meya D, Nakiyingi L et al (2012) The impact of early monitored management on survival in hospitalized adult Ugandan patients with severe sepsis: a prospective intervention study. Crit Care Med 40:2050–2058

Maitland K, Kiguli S, Opoka RO, Engoru C, Olupot-Olupot P, Akech SO et al (2011) Mortality after fluid bolus in African children with severe infection. N Engl J Med 364:2483–2495

Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Carlet JM, Bion J, Parker MM, Jaeschke R et al (2008) Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2008. Crit Care Med 36:296–327

NICE (2013) Clinical guideline: intravenous fluid therapy in adults in hospital. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, uk

Dunser MW, Baelani I, Ganbold L (2006) A review and analysis of intensive care medicine in the least developed countries. Crit Care Med 34:1234–1242

Adhikari NK, Rubenfeld GD (2011) Worldwide demand for critical care. Curr Opin Crit Care 17:620–625

Jacob ST, Lim M, Banura P, Bhagwanjee S, Bion J, Cheng AC et al (2013) Integrating sepsis management recommendations into clinical care guidelines for district hospitals in resource-limited settings: the necessity to augment new guidelines with future research. BMC Med 11:107

Gosselin RA, Heitto M (2008) Cost-effectiveness of a district trauma hospital in Battambang, Cambodia. World J Surg 32:2450–2453

Stafford RE, Morrison CA, Godfrey G, Mahalu W (2014) Challenges to the provision of emergency services and critical care in resource-constrained settings. Glob Heart 9:319–323

Vukoja M, Riviello E, Gavrilovic S, Adhikari NK, Kashyap R, Bhagwanjee S et al (2014) A survey on critical care resources and practices in low- and middle-income countries. Glob Heart 9(337–342):e335

Chimwaza W, Chipeta E, Ngwira A, Kamwendo F, Taulo F, Bradley S et al (2014) What makes staff consider leaving the health service in Malawi? Human Res Health 12:17

West MA, Guthrie JP, Dawson JF, Borrill CS, Carter M (2006) Reducing patient mortality in hospitals: the role of human resource management. J Organ Behav 27:983–1002

Andrews B, Muchemwa L, Kelly P, Lakhi S, Heimburger DC, Bernard GR (2014) Simplified severe sepsis protocol: a randomized controlled trial of modified early goal-directed therapy in Zambia. Crit Care Med 42:2315–2324

Vukoja M, Kashyap R, Gavrilovic S, Dong Y, Kilickaya O, Gajic O (2015) Checklist for early recognition and treatment of acute illness: international collaboration to improve critical care practice. World J Crit Care Med 4:55–61

Authors’ contributions

COS designed the study, acquired, analysed and interpreted the data, and drafted and revised the manuscript. MC designed the study, interpreted the data and revised the manuscript. EL contributed to the design of the study, acquired the data and revised the manuscript. JB contributed to the conception and design of the study, data interpretation and revised the manuscript. MM contributed to the design of the study and revised the manuscript. DK contributed to the conception and design of the study and revised the manuscript. TB designed the study, interpreted the data, and drafted and revised the manuscript. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Jaran Eriksen, Martin Dunser and Tim Stephens for input into the VSDT protocol. Thank you to Agness Laizer, Erasto Kalinga, Elizabeth Stephens, Nazahed Richards, Ulrica Mickelsson and Charlotte Förars for practical assistance in data collection and supporting the study. Thank you to the leadership of Muhimbili National Hospital and to all those involved in the MKAIC collaboration and Life Support Foundation for making the study feasible. The study was funded by grants from the Laerdal Foundation, the Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland, the Karolinska Institutet Travel Grant and R&D funds by Sörmland County Council. The funding sources had no role in the design, conduct or reporting of the study.

Compliance with ethical guidelines

Competing interests The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

An erratum to this article is available at https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-017-2554-4.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Schell, C.O., Castegren, M., Lugazia, E. et al. Severely deranged vital signs as triggers for acute treatment modifications on an intensive care unit in a low-income country. BMC Res Notes 8, 313 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-015-1275-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-015-1275-9