Abstract

Critical care medicine is a global specialty and epidemiologic research among countries provides important data on availability of critical care resources, best practices, and alternative options for delivery of care. Understanding the diversity across healthcare systems allows us to explore that rich variability and understand better the nature of delivery systems and their impact on outcomes. However, because the delivery of ICU services is complex (for example, interplay of bed availability, cultural norms and population case-mix), the diversity among countries also creates challenges when interpreting and applying data. This complexity has profound influences on reported outcomes, often obscuring true differences. Future research should emphasize determination of resource data worldwide in order to understand current practices in different countries; this will permit rational pandemic and disaster planning, allow comparisons of in-ICU processes of care, and facilitate addition of pre- and post-ICU patient data to better interpret outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In just over 50 years, the practice of critical care medicine has spread to nearly every country in the world. Some aspects of caring for critically ill patients are universal, while others are particular to a specific country or healthcare system. Given the similarities and differences in critical care among countries and regions, comparisons can provide important information regarding best practice or alternative options for delivery of care. To date, international critical care research has provided information regarding available resources across borders, allowed us to understand the consequences of different approaches to care, and illuminated features and mechanisms that could potentially improve outcomes if implemented elsewhere. Yet, we have also learned to view international data with caution, as we begin to understand the magnitude of the differences in healthcare systems and the challenges these differences present for interpretation of data. This article will outline important information we have gained from international comparison of critical care, address the challenges of such studies, and outline areas for future research.

The importance of international critical care research

Healthcare delivery occurs at the individual patient level, within a local healthcare structure that is in turn influenced by the larger regional or national system. Understanding and comparing care across systems, and particularly across countries, may provide valuable insights that can impact both policy and care (Table 1). First, as the threat of disasters and pandemics continues to grow, an accurate understanding of available resources, and the capacity to deliver intensive care, is crucial. International organizations and policy discussions focus on the need to determine the capacity to handle potential surges in the demand for critical care resources [1, 2]. Pandemic influenza, for example, recently revealed the limitations of current knowledge of ICU beds both locally and internationally, highlighting the urgent need for accurate resource data [2].

Second, new treatments and techniques studied within a single country or across countries are frequently implemented in the care of critically ill patients worldwide [3, 4]. Knowledge of variation in approaches to care, such as nutrition [5], mechanical ventilation [6], or end-of-life decisions [7], are important for appropriate interpretation and broad application of study results. For example, a study of tight glucose control in one country may not be easily or safely implemented in another if the timing and route of feeding differ regardless of the reported utility in the original study center [3, 8]. Additionally, as investigators recognize that large effect sizes are not necessarily obtainable, more studies are powered for smaller, more realistic effect sizes [9, 10], necessitating larger populations of critically ill patients and pooling of patient data from several healthcare systems. A recent report from an international roundtable focused on improving clinical trials specifically recommended the formation of critical care clinical trials groups that can operate across national boundaries [11].

Third, the role of critical care in overall healthcare continues to evolve. There is much to learn from examining different healthcare systems regarding the choices of how much, when, and in what capacity to deliver critical care [12]. These issues impact on optimizing the quality of care and minimizing costs. While spending on critical care differs across countries, the drive to reduce costs (while maintaining quality) is universal. Hence, international comparisons that allow understanding of differences in the use of specific approaches in ICUs, as well as the associated costs and outcomes, may facilitate design of optimal ICU resource distribution and practices.

Variation in resources

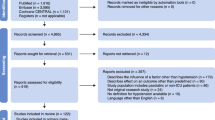

Due to the urgency created by pandemics and natural disasters, we have increased our understanding of the availability of resources worldwide (Figure 1), with recent studies documenting the variation in availability of ICU beds [12, 13]. In particular, we have learned that there is an eight-fold difference in the availability of ICU beds in developed countries, ranging from 3 to 25 ICU beds/100,000 population in the United Kingdom and Germany, respectively [13]. Yet, in many countries the ICU capacity remains unknown [12].

Global variation in intensive care unit beds per 100,000 population (adapted from [12]).

What is an ICU bed?

A key issue that emerges from such comparisons is the definition of an 'ICU bed'. American definitions reflect the intensity of staffing (for example, nurse to patient ratio, intensity of physician staffing) [13]. In contrast, definitions of ICU beds in Belgium reflect the intensity of the illness and focus on the ability to care for patients with specific severities of illness (that is, organ dysfunction) [13]. This variability in definition of intensive care (different staffing intensity, different patient type or acuity) clearly impacts the ability to compare care for critically ill patients. Even without a universal definition of an ICU bed, however, the variation in availability of any type of ICU bed remains large.

What is the impact of having more or fewer ICU beds?

International comparisons demonstrate that different availability of ICU beds is associated with variation in admission rates and in the case-mix of patients admitted to ICU. A comparison of administrative data for the province of Alberta (Canada) versus four counties in Western Massachusetts (with more ICU beds per capita) found that hospitalized patients in Western Massachusetts had a much higher frequency of admission to ICU [14]. A similar study of patients in the US and the UK found an eight-fold difference in ICU admission rates for hospitalized patients, despite similar per capita hospitalization rates [15].

What do the ICU patients look like?

In studies comparing US ICU patients to patients in the UK [16], Japan [17], and New Zealand [18] (all with fewer ICU beds), US ICU patients were consistently older, but less severely ill. In a direct comparison of medical ICU admissions in the US and UK, the average Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Points (APACHE) II score was substantially lower for US versus UK patients (15.3 ± 8 versus 20.5 ± 8.5), with far fewer patients mechanically ventilated in US ICUs (21.1% versus 53.7%) [16]. Finally, there are important differences in the reasons for admission: in the US almost 40% of all ICU admissions are for monitoring purposes only, rather than for any kind of active treatment requiring intensive care [19].

Differences in bed availability affect the diagnosis as well as the age and severity of illness of patients. Among European countries with similar healthcare spending per capita, data indicate that the incidence of severe sepsis in critical care units varies: sepsis accounts for 10% of ICU admissions in Switzerland and 64% of admissions in Portugal [20]. The frequency of sepsis in the ICU strongly correlates with the number of ICU beds per capita such that countries with fewer beds have a greater proportion of their beds occupied by patients with sepsis [13]. Similarly, the incidence of acute renal failure in critically ill patients varies dramatically from 3.3% in Germany (with many ICU beds) to 20.6% in the UK (with eight-fold fewer ICU beds [21]. These findings are consistent with the idea that countries with few ICU beds reserve those beds for the most severely ill patients (that is, with sepsis or renal failure), and do not have the resources to also admit patients with many other less life-threatening diseases. Taken together, such data suggest that ICU case-mix is strongly influenced by availability of ICU beds in any given population [13].

Patterns of care

International studies demonstrate that differences in the availability of ICU beds impacts not only the ICU case-mix, but can impact also the patterns of care for patients in the hospital.

Insufficient ICU beds and mortality

Having few ICU beds may result in either refusal of intensive care or delayed admission. A UK study tracking 817 patients referred for ICU admission reported initial refusal of 168 (21%), with over half of the refusals due to a lack of beds. Although confounded, the 'raw' mortality for those refused was significantly higher than for those admitted to ICU [22]. A systematic review by Sinuff and colleagues [23] confirmed that hospital mortality is increased three-fold for patients refused ICU admission; however, refusals may sometimes just reflect changes in goals of care or prognosis.

Insufficient ICU beds and delayed admission

A more common issue is delayed ICU admission because of a lack of beds. More ICU beds may mean easier access for 'emergency' patients. For example, in a direct comparison of the US with Japan (where there are fewer beds), only 15% of patients were admitted from the Emergency Department (ED) (versus 34% in the US) [17]. In a similar study comparing the US with the UK, 58% were admitted directly to ICU from the ED in the US, compared with only 33% in the UK [16]. The less 'direct' transfer from ED to ICU in the UK was associated with a substantially longer time in hospital before ICU admission, and (even after adjustment for case-mix) was associated with higher mortality. The worse outcomes in critically ill patients associated with transfer delay or refusal of ICU admission underscore the importance of detecting and learning from such comparisons [24–26].

Use of invasive therapies

Variation in patterns of care across countries may also extend to the choice to offer mechanical ventilation or other therapies. These differences may even be visible in randomized controlled trials. For example, a trial from the UK of non-invasive ventilation for acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema versus standard oxygen treatment found no difference in the primary outcome, defined as death within 7 days. While 9.5% of patients died within 7 days, only 2.9% were intubated and only 50% admitted to an ICU [27]. In contrast, usual practice, as indicated by the control group of a similar US study, suggested intubation rates ten-fold higher than in the UK [28].

Impact on validity of scoring systems

Understanding differences in care patterns before ICU admission may explain why many mortality prediction models, such as the APACHE or Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS), require adjustment in different regions or countries [29–31]. The original US APACHE II model showed variable ability to accurately predict risk of death when applied to UK patients, leading to a 'local' UK recalibration of the model [30]. Patients who experience different delays in transfer to ICU or variable quality of pre-ICU care will likely demonstrate different physiologic derangements upon admission, thus changing the model performance [32]. In considering this there are two extremes. Inadequate resuscitation on a poorly equipped general ward may result in greater physiological deterioration. Alternatively, excellent resuscitation in the ED or a general ward could result in stability and fewer physiologic derangements on ICU admission; such patients may not look as 'sick' in terms of a given (physiologic) scoring system, but may do poorly because of the true severity of their underlying disease. One study compared APACHE II, APACHE III and SAPS II scores using standard calculations, and then taking into account pre-ICU data [32]. The predicted mortality for patients incorporating the pre-admission data was substantially higher than the mortality based on standard calculations, suggesting a 'lead time bias' associated with scoring systems. Therefore, the different performance of these scores across units and countries can highlight care delivery factors that should be explored and changed. Given the substantial variation in admission practices, interpretation of ICU outcomes necessitates understanding of the delivery of pre-ICU care, including that in the ED, the ward, or the pre-hospital setting.

Care provided after ICU admission

Variability naturally occurs in the care provided after ICU admission. For example, treatments for severe sepsis differ among critical care settings. Data from the PROGRESS (Promoting Global Research Excellence in Severe Sepsis) observational sepsis registry demonstrated that use of low-dose steroids for severe sepsis appeared to be region-specific, with European countries using steroids at double the rate of Asian countries [33]. Moreover, fluid resuscitation varied by upwards of 30% among nations [34]. Developing regions are especially vulnerable to variability, with very inconsistent application of goal-directed sepsis treatment across Africa [35]. Even between neighboring countries of comparable socioeconomic parameters, care patterns may differ dramatically. For example, United States hospitals perform coronary angiography on patients with acute myocardial infarctions nearly five times as frequently as patients cared for in Canadian hospitals [36].

Discharge from ICU

We now know that different discharge practices impact on interpretation of outcome data, particularly short-term measurements. Length of stay in acute care hospitals is variable and region specific; patients in Canada, Japan, and England generally remain hospitalized in acute care facilities for longer than patients in the US [37]. For example, patients with a myocardial infarction and with a similar severity of illness had a 12 day longer hospital stay in Germany versus the US [38], and general medical ICU patients stratified by severity of illness had consistently longer hospital lengths of stay in the UK versus the US [16]. While severity of illness clearly impacts length of stay, other factors, such as reimbursement schemes (which may reward or penalize hospitals - or patients - for short stays), cultural expectations, clinical guidelines, and alternatives for further care, may also play a role.

How does post-ICU care influence ICU discharge patterns?

The availability of alternative care options may drive models of care, which in turn impact on patterns of reported morbidity and mortality. In the US in particular, there has been large growth of both sub-acute nursing facilities and long- term acute care facilities, the mandate of which is to care for the chronically critically ill [39, 40]. Up to 33% of Medicare patients cared for in ICUs in the US are now discharged to such facilities [40, 41]. Transferring high -risk patients from ICUs to other care facilities can alter the reported ICU (and hospital) length of stay and mortality, thereby altering the perceived efficacy of ICU-specific interventions and care. One simulation demonstrated that an increase of transfers of just 6% could change the hospital standardized mortality ratio by up to 15% [42], and a recent study of 137 hospitals found a strong inverse correlation between the transfer rate to long-term acute care facilities and mortality (as well as hospital length of stay) [43].

Such alternative care options exist predominantly in the US, and have not been as widely integrated into many other health systems. Because of this, hospital-based outcomes after critical illness in the US are difficult to compare with those in other countries. For example, in a direct comparison of severely ill medical ICU patients with high Acute Physiology Scores (>20), the length of hospital stay was shorter in the US compared with the UK; however, this was confounded by the transfer of over half of the ICU patients in the US (53.9%) to a skilled care facility versus only 7.9% in the UK [16]. Longer-term follow-up studies can overcome such confounders, but such studies may be prohibitively expensive and time-consuming. An alternative approach may be the use of 'discharge home' rather than mortality as a short-term comparator. While patients may remain in an acute hospital (or elsewhere) after ICU, the ability to return home likely requires a more consistent (and comparable) level of function across most healthcare systems.

Culture, reimbursement and chronic disease

Culture and religion can be large drivers of medical care to the extent of over-riding scientific evidence or guidelines [44]. A good example in the ICU is end-of-life care. Here, practices are diverse, with centers in some regions in Europe two to three times as likely as others to withdraw life-sustaining treatment [7, 45, 46]. Mirroring this variability, the utilization of resuscitation directives varies significantly, even between cities [47]. Within countries, significant religious and cultural differences exist among physicians and appear to have a large impact on end-of-life practices, with the median time from ICU admission to any limitation of therapy varying by as much as 6 days, depending upon physician religion [48]. Societal differences are also apparent with regard to chronically critically ill patients; the willingness to maintain technology-dependent lifestyles varies, as seen with neonatal resuscitation [49]. The sizable impact of patient (and provider) culture and religion on critical care practice and outcomes is undeniable, and needs to be considered in the incorporation of international data into local practice and policy.

Differing health insurance schemes and socio-economic divisions also introduce substantial variation in how patients are treated, both in terms of likelihood of admission to ICU and care in the ICU. For example, most patients in Chinese ICUs have some form of private health insurance, although the majority of Chinese citizens have none [50]. US patients without health insurance use critical care resources at a lower rate than those with insurance, but subsequently have higher mortality rates due to greater severity of illness [51]. Moreover, once admitted to the ICU, uninsured patients in the US receive fewer procedures, have more hospital discharge delays and are more likely to have life support withdrawn [52].

The burden of acute and chronic disease is also markedly different between regions. Perhaps the best demonstration of these differences is the work by Banks and colleagues [53], who studied similarly constructed cohorts of middle class Americans and British. The study found that late middle-aged Americans had an additional burden of many chronic diseases. For example, among those aged 55 to 64 years, the diabetes prevalence was twice as high in the US cohort, and heart disease occurred in 15% (versus 10% in England). This higher burden of chronic disease may both increase the predisposition to develop chronic illness and worsen outcomes.

Priorities for future international research

Awareness of the world-wide variability in delivery of critical care is a first step in understanding the drivers and consequences of such differences and can lead to the development of testable hypotheses concerning delivery of care. For example, important differences in feeding strategies for critically ill patients in North America versus Europe led to a large randomized controlled trial [54, 55], which supported avoidance of early and aggressive parenteral nutrition. Other areas for research include provision of detailed information regarding ICU resources worldwide, improvement of scoring systems to allow for accurate comparisons across heterogeneous populations, and more sophisticated analysis of the 'international meaning' of short- and long-term mortality. This necessitates the development of even stronger international collaborations and an open approach to data sharing [11, 56].

Our knowledge of the availability of critical care beds in developing countries also lags [57]. Work by Adhikari and colleagues [12] summarizing availability of ICU beds worldwide provides few data for Africa (with the exception of South Africa). Survey data from Zambia suggest there are only 0.2 ICU beds per 100 hospital beds, far below the averages for developed countries [58]. The case-mix is, naturally, quite different in these regions, with estimates that infections account for over half of all deaths, compared with 6% in high-income countries [12]. A better understanding of the role of critical care outside of the developed world is clearly an area for future work, as is the development of severity of illness scores that are simple yet robust enough to implement and collect across a wide range of critical care settings. The lack of an effective pediatric risk prediction tool that is useful and validated across borders is another research opportunity, given the global burden of pediatric critical illness [59].

Determining the optimal period of follow-up to best capture long-term mortality for a critical-illness intervention is a topic of much debate [60]. Given the variability in discharge practices, as well as the protean choices regarding end-of-life care, it is apparent that extending patient follow-up past location-based censoring at 28 days or hospital discharge is important. In addition, we must develop non-mortality outcomes that are not merely ICU-specific, but patient-centered, incorporating measures of disability, functional capacity, and end-of-life preferences.

Conclusion

With the advent of large databases and ease of international collaborations, we can look beyond local hospitals and healthcare systems to gain insight from the differences among practices. Many studies comparing regions and countries now document large variation in the delivery of critical care, and by understanding the causes (and consequences) of these differences, we can interpret international data more accurately. However, the very differences that make comparisons across countries difficult are also the areas that warrant further investigation to ultimately optimize local delivery of care and outcomes.

Abbreviations

- APACHE:

-

Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation

- ED:

-

Emergency Department

- ICU:

-

intensive care unit

- SAPS:

-

Simplified Acute Physiology Score.

References

Carr BG, Addyson DK, Kahn JM: Variation in critical care beds per capita in the United States: implications for pandemic and disaster planning. JAMA 2010, 303: 1371-1372. 10.1001/jama.2010.394

Sprung CL, Zimmerman JL, Christian MD, Joynt GM, Hick JL, Taylor B, Richards GA, Sandrock C, Cohen R, Adini B: Recommendations for intensive care unit and hospital preparations for an influenza epidemic or mass disaster: summary report of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine's Task Force for intensive care unit triage during an influenza epidemic or mass disaster. Intensive Care Med 2010, 36: 428-443. 10.1007/s00134-010-1759-y

van den Berghe G, Wouters P, Weekers F, Verwaest C, Bruyninckx F, Schetz M, Vlasselaers D, Ferdinande P, Lauwers P, Bouillon R: Intensive insulin therapy in the critically ill patients. N Engl J Med 2001, 345: 1359-1367. 10.1056/NEJMoa011300

Rivers E, Nguyen B, Havstad S, Ressler J, Muzzin A, Knoblich B, Peterson E, Tomlanovich M: Early goal-directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med 2001, 345: 1368-1377. 10.1056/NEJMoa010307

Preiser JC, Berre J, Carpentier Y, Jolliet P, Pichard C, Van Gossum A, Vincent JL: Management of nutrition in European intensive care units: results of a questionnaire. Working Group on Metabolism and Nutrition of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med 1999, 25: 95-101. 10.1007/s001340050793

Esteban A, Anzueto A, Frutos F, Alía I, Brochard L, Stewart TE, Benito S, Epstein SK, Apezteguía C, Nightingale P, Arroliga AC, Tobin MJ, Mechanical Ventilation International Study Group: Characteristics and outcomes in adult patients receiving mechanical ventilation: a 28-day international study. JAMA 2002, 287: 345-355. 10.1001/jama.287.3.345

Sprung CL, Cohen SL, Sjokvist P, Baras M, Bulow HH, Hovilehto S, Ledoux D, Lippert A, Maia P, Phelan D, Schobersberger W, Wennberg E, Woodcock T, Ethicus Study Group: End-of-life practices in European intensive care units: the Ethicus Study. JAMA 2003, 290: 790-797. 10.1001/jama.290.6.790

Kavanagh BP, McCowen KC: Clinical practice. Glycemic control in the ICU. N Engl J Med 2010, 363: 2540-2546. 10.1056/NEJMcp1001115

CRASH-2 collaborators, Roberts I, Shakur H, Afolabi A, Brohi K, Coats T, Dewan Y, Gando S, Guyatt G, Hunt BJ, Morales C, Perel P, Prieto-Merino D, Woolley T: The importance of early treatment with tranexamic acid in bleeding trauma patients: an exploratory analysis of the CRASH-2 randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2011, 377: 1096-1101. 1101.e1091-1092

Siontis GC, Ioannidis JP: Risk factors and interventions with statistically significant tiny effects. Int J Epidemiol 2011, 40: 1292-1307. 10.1093/ije/dyr099

Angus DC, Mira JP, Vincent JL: Improving clinical trials in the critically ill. Crit Care Med 2010, 38: 527-532. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181c0259d

Adhikari NK, Fowler RA, Bhagwanjee S, Rubenfeld GD: Critical care and the global burden of critical illness in adults. Lancet 2010, 376: 1339-1346. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60446-1

Wunsch H, Angus DC, Harrison DA, Collange O, Fowler R, Hoste EA, de Keizer NF, Kersten A, Linde-Zwirble WT, Sandiumenge A, Rowan KM: Variation in critical care services across North America and Western Europe. Crit Care Med 2008, 36: 2787-2793. e2781-2789 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318186aec8

Rapoport J, Teres D, Barnett R, Jacobs P, Shustack A, Lemeshow S, Norris C, Hamilton S: A comparison of intensive care unit utilization in Alberta and western Massachusetts. Crit Care Med 1995, 23: 1336-1346. 10.1097/00003246-199508000-00006

Wunsch H, Linde-Zwirble WT, Harrison DA, Barnato AE, Rowan KM, Angus DC: Use of intensive care services during terminal hospitalizations in England and the United States. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009, 180: 875-880. 10.1164/rccm.200902-0201OC

Wunsch H, Angus DC, Harrison DA, Linde-Zwirble WT, Rowan KM: Comparison of medical admissions to intensive care units in the United States and United kingdom. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011, 183: 1666-1673. 10.1164/rccm.201012-1961OC

Sirio CA, Tajimi K, Taenaka N, Ujike Y, Okamoto K, Katsuya H: A cross-cultural comparison of critical care delivery: Japan and the United States. Chest 2002, 121: 539-548. 10.1378/chest.121.2.539

Zimmerman JE, Knaus WA, Judson JA, Havill JH, Trubuhovich RV, Draper EA, Wagner DP: Patient selection for intensive care: a comparison of New Zealand and United States hospitals. Crit Care Med 1988, 16: 318-326. 10.1097/00003246-198804000-00003

Zimmerman JE, Kramer AA: A model for identifying patients who may not need intensive care unit admission. J Crit Care 2010, 25: 205-213. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2009.06.010

Vincent JL, Sakr Y, Sprung CL, Ranieri VM, Reinhart K, Gerlach H, Moreno R, Carlet J, Le Gall JR, Payen D: Sepsis in European intensive care units: results of the SOAP study. Crit Care Med 2006, 34: 344-353. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000194725.48928.3A

Uchino S, Kellum JA, Bellomo R, Doig GS, Morimatsu H, Morgera S, Schetz M, Tan I, Bouman C, Macedo E, Gibney N, Tolwani A, Ronco C, Beginning and Ending Supportive Therapy for the Kidney (BEST Kidney) Investigators: Acute renal failure in critically ill patients: a multinational, multicenter study. JAMA 2005, 294: 813-818. 10.1001/jama.294.7.813

Metcalfe MA, Sloggett A, McPherson K: Mortality among appropriately referred patients refused admission to intensive-care units. Lancet 1997, 350: 7-11. 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)10018-0

Sinuff T, Kahnamoui K, Cook DJ, Luce JM, Levy MM: Rationing critical care beds: a systematic review. Crit Care Med 2004, 32: 1588-1597. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000130175.38521.9F

Chalfin DB, Trzeciak S, Likourezos A, Baumann BM, Dellinger RP: Impact of delayed transfer of critically ill patients from the emergency department to the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 2007, 35: 1477-1483. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000266585.74905.5A

Rincon F, Mayer SA, Rivolta J, Stillman J, Boden-Albala B, Elkind MS, Marshall R, Chong JY: Impact of delayed transfer of critically ill stroke patients from the Emergency Department to the Neuro-ICU. Neurocrit Care 2010, 13: 75-81. 10.1007/s12028-010-9347-0

Goldhill DR, McNarry AF, Hadjianastassiou VG, Tekkis PP: The longer patients are in hospital before Intensive Care admission the higher their mortality. Intensive Care Med 2004, 30: 1908-1913. 10.1007/s00134-004-2386-2

Gray A, Goodacre S, Newby DE, Masson M, Sampson F, Nicholl J: Noninvasive ventilation in acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema. N Engl J Med 2008, 359: 142-151. 10.1056/NEJMoa0707992

Levitt MA: A prospective, randomized trial of BiPAP in severe acute congestive heart failure. J Emerg Med 2001, 21: 363-369. 10.1016/S0736-4679(01)00385-7

Rowan KM, Kerr JH, Major E, McPherson K, Short A, Vessey MP: Intensive Care Society's APACHE II study in Britain and Ireland- I: Variations in case mix of adult admissions to general intensive care units and impact on outcome. BMJ 1993, 307: 972-977. 10.1136/bmj.307.6910.972

Rowan KM, Kerr JH, Major E, McPherson K, Short A, Vessey MP: Intensive Care Society's APACHE II study in Britain and Ireland--II: Outcome comparisons of intensive care units after adjustment for case mix by the American APACHE II method. BMJ 1993, 307: 977-981. 10.1136/bmj.307.6910.977

Harrison DA, Brady AR, Parry GJ, Carpenter JR, Rowan K: Recalibration of risk prediction models in a large multicenter cohort of admissions to adult, general critical care units in the United Kingdom. Crit Care Med 2006, 34: 1378-1388. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000216702.94014.75

Tunnell RD, Millar BW, Smith GB: The effect of lead time bias on severity of illness scoring, mortality prediction and standardised mortality ratio in intensive care - a pilot study. Anaesthesia 1998, 53: 1045-1053. 10.1046/j.1365-2044.1998.00566.x

Beale R, Janes JM, Brunkhorst FM, Dobb G, Levy MM, Martin GS, Ramsay G, Silva E, Sprung CL, Vallet B, Vincent JL, Costigan TM, Leishman AG, Williams MD, Reinhart K: Global utilization of low-dose corticosteroids in severe sepsis and septic shock: a report from the PROGRESS registry. Crit Care 2010, 14: R102. 10.1186/cc8334

Beale R, Reinhart K, Brunkhorst FM, Dobb G, Levy M, Martin G, Martin C, Ramsey G, Silva E, Vallet B, Vincent JL, Janes JM, Sarwat S, Williams MD, PROGRESS Advisory Board: Promoting Global Research Excellence in Severe Sepsis (PROGRESS): lessons from an international sepsis registry. Infection 2009, 37: 222-232.

Baelani I, Jochberger S, Laimer T, Otieno D, Kabutu J, Wilson I, Baker T, Dunser MW: Availability of critical care resources to treat patients with severe sepsis or septic shock in Africa: a self-reported, continent-wide survey of anaesthesia providers. Crit Care 2011, 15: R10. 10.1186/cc9410

Tu JV, Pashos CL, Naylor CD, Chen E, Normand SL, Newhouse JP, McNeil BJ: Use of cardiac procedures and outcomes in elderly patients with myocardial infarction in the United States and Canada. N Engl J Med 1997, 336: 1500-1505. 10.1056/NEJM199705223362106

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development:OECD Health Data. 2011. [http://www.oecd.org/document/30/0,3746,en_2649_37407_12968734_1_1_1_37407,00.html]

Kaul P, Newby LK, Fu Y, Mark DB, Califf RM, Topol EJ, Aylward P, Granger CB, Van de Werf F, Armstrong PW: International differences in evolution of early discharge after acute myocardial infarction. Lancet 2004, 363: 511-517. 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15536-0

Kramer AA, Zimmerman JE: Institutional variations in frequency of discharge of elderly intensive care survivors to postacute care facilities. Crit Care Med 2010, 38: 2319-2328. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181fa02e4

Kahn JM, Benson NM, Appleby D, Carson SS, Iwashyna TJ: Long-term acute care hospital utilization after critical illness. JAMA 2010, 303: 2253-2259. 10.1001/jama.2010.761

Wunsch H, Guerra C, Barnato AE, Angus DC, Li G, Linde-Zwirble WT: Three-year outcomes for Medicare beneficiaries who survive intensive care. JAMA 2010, 303: 849-856. 10.1001/jama.2010.216

Kahn JM, Kramer AA, Rubenfeld GD: Transferring critically ill patients out of hospital improves the standardized mortality ratio: a simulation study. Chest 2007, 131: 68-75. 10.1378/chest.06-0741

Hall WB, Willis LE, Medvedev S, Carson SS: The implications of long term acute care hospital transfer practices for measures of in-hospital mortality and length of stay. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012, 185: 53-57. 10.1164/rccm.201106-1084OC

Payer L: Medicine and Culture: Varieties of Treatment in the United States, England, West Germany, and France. New York, NY: Henry Holt and Co; 1988.

Frost DW, Cook DJ, Heyland DK, Fowler RA: Patient and healthcare professional factors influencing end-of-life decision-making during critical illness: a systematic review. Crit Care Med 2011, 39: 1174-1189. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31820eacf2

Ball CG, Navsaria P, Kirkpatrick AW, Vercler C, Dixon E, Zink J, Laupland KB, Lowe M, Salomone JP, Dente CJ, Wyrzykowski AD, Hameed SM, Widder S, Inaba K, Ball JE, Rozycki GS, Montgomery SP, Hayward T, Feliciano DV: The impact of country and culture on end-of-life care for injured patients: results from an international survey. J Trauma 2010, 69: 1323-1333. discussion 1333-1324 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181f66878

Cook DJ, Guyatt G, Rocker G, Sjokvist P, Weaver B, Dodek P, Marshall J, Leasa D, Levy M, Varon J, Fisher M, Cook R: Cardiopulmonary resuscitation directives on admission to intensive-care unit: an international observational study. Lancet 2001, 358: 1941-1945. 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06960-4

Sprung CL, Maia P, Bulow HH, Ricou B, Armaganidis A, Baras M, Wennberg E, Reinhart K, Cohen SL, Fries DR, Nakos G, Thijs LG, Ethicus Study Group: The importance of religious affiliation and culture on end-of-life decisions in European intensive care units. Intensive Care Med 2007, 33: 1732-1739. 10.1007/s00134-007-0693-0

Miljeteig I, Sayeed SA, Jesani A, Johansson KA, Norheim OF: Impact of ethics and economics on end-of-life decisions in an Indian neonatal unit. Pediatrics 2009, 124: e322-328. 10.1542/peds.2008-3227

Du B, Xi X, Chen D, Peng J: Clinical review: critical care medicine in mainland China. Crit Care 2010, 14: 206. 10.1186/cc8222

Danis M, Linde-Zwirble WT, Astor A, Lidicker JR, Angus DC: How does lack of insurance affect use of intensive care? A population-based study. Crit Care Med 2006, 34: 2043-2048. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000227657.75270.C4

Fowler RA, Noyahr LA, Thornton JD, Pinto R, Kahn JM, Adhikari NK, Dodek PM, Khan NA, Kalb T, Hill A, O'Brien JM, Evans D, Curtis JR, American Thoracic Society Disparities in Healthcare Group: An official American Thoracic Society systematic review: the association between health insurance status and access, care delivery, and outcomes for patients who are critically ill. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010, 181: 1003-1011. 10.1164/rccm.200902-0281ST

Banks J, Marmot M, Oldfi eld Z, Smith JP: Disease and disadvantage in the United States and in England. JAMA 2006, 295: 2037-2045. 10.1001/jama.295.17.2037

Cahill NE, Dhaliwal R, Day AG, Jiang X, Heyland DK: Nutrition therapy in the critical care setting: what is "best achievable" practice? An international multicenter observational study. Crit Care Med 2010, 38: 395-401.

Casaer MP, Mesotten D, Hermans G, Wouters PJ, Schetz M, Meyfroidt G, Van Cromphaut S, Ingels C, Meersseman P, Muller J, Vlasselaers D, Debaveye Y, Desmet L, Dubois J, Van Assche A, Vanderheyden S, Wilmer A, Van den Berghe G: Early versus late parenteral nutrition in critically ill adults. N Engl J Med 2011, 365: 506-517.

InFACT: a global critical care research response to H1N1 Lancet 2010, 375: 11-13.

Riviello ED, Letchford S, Achieng L, Newton MW: Critical care in resource-poor settings: lessons learned and future directions. Crit Care Med 2011, 39: 860-867.

Jochberger S, Ismailova F, Lederer W, Mayr VD, Luckner G, Wenzel V, Ulmer H, Hasibeder WR, Dunser MW: Anesthesia and its allied disciplines in the developing world: a nationwide survey of the Republic of Zambia. Anesth Analg 2008, 106: 942-948. 10.1213/ane.0b013e318166ecb8

Rodgers A, Ezzati M, Vander Hoorn S, Lopez AD, Lin RB, Murray CJ: Distribution of major health risks: findings from the Global Burden of Disease study. PLoS Med 2004, 1: e27. 10.1371/journal.pmed.0010027

Rubenfeld GD: Improving clinical trials of long-term outcomes. Crit Care Med 2009,37(1 Suppl):S112-116.

Acknowledgements

Supported by award number K08AG038477 from the National Institute on Aging to HW.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Murthy, S., Wunsch, H. Clinical review: International comparisons in critical care - lessons learned. Crit Care 16, 218 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/cc11140

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/cc11140