Abstract

Background

To determine the prevalence of sustained remission/low disease activity (LDA) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) after discontinuation of tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi), separately in induction treatment and maintenance treatment studies, and to identify predictors of successful discontinuation.

Methods

We performed a systematic literature review of studies published from 2005 to May 2022 that reported outcomes after TNFi discontinuation among patients in remission/LDA. We computed prevalences of successful discontinuation by induction or maintenance treatment, remission criterion, and follow-up time. We performed a scoping review of predictors of successful discontinuation.

Results

Twenty-two induction-withdrawal studies were identified. In pooled analyses, 58% (95% confidence interval (CI) 45, 70) had DAS28 < 3.2 (9 studies), 52% (95% CI 35, 69) had DAS28 < 2.6 (9 studies), and 40% (95% CI 18, 64) had SDAI ≤ 3.3 (4 studies) at 37–52 weeks after discontinuation. Among patients who continued TNFi, 62 to 85% maintained remission. Twenty-two studies of maintenance treatment discontinuation were also identified. At 37–52 weeks after TNFi discontinuation, 48% (95% CI 38, 59) had DAS28 < 3.2 (10 studies), and 47% (95% CI 33, 62) had DAS28 < 2.6 (6 studies). Heterogeneity among studies was high. Data on predictors in induction-withdrawal studies were limited. In both treatment scenarios, longer duration of RA was most consistently associated with less successful discontinuation.

Conclusions

Approximately one-half of patients with RA remain in remission/LDA for up to 1 year after TNFi discontinuation, with slightly higher proportions in induction-withdrawal settings than with maintenance treatment discontinuation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

With recent advances in therapy, the current goal of treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is clinical remission. While 30% of patients treated with conventional synthetic disease-modifying medications (csDMARDs) achieve remission, up to 50% of those treated with tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi) in a treat-to-target strategy achieve remission at 6 to 12 months, with better physical functioning, less radiographic damage, and lower risks of work loss [1,2,3].

With this growing population of patients, new questions have arisen about the most appropriate regimen to maintain remission. In particular, for patients treated with TNFi in combination with csDMARDs, what are the relative benefits and risks of continuing versus discontinuing TNFi? Discontinuation of TNFi could avoid potential overtreatment and eliminate associated costs and risks of toxicities [4]. Also, because patients in remission may experiment with unsupervised drug holidays, supervised discontinuation may improve overall adherence [5, 6]. However, TNFi discontinuation entails risks of increased RA activity. Previous reviews have reported that 40 to 50% of patients could maintain remission at least short-term after stopping TNFi, but loss of remission was 1.3 to 6.7 times more likely compared to those who continued treatment [4, 7,8,9,10,11,12].

TNFi discontinuation may take place in two clinical contexts: when remission has been achieved after short-term use of TNFi as induction therapy (i.e., an induction-withdrawal approach), or more commonly, among patients in stable remission after long-term treatment (i.e., maintenance discontinuation). Viewed in the Population-Intervention-Comparator-Outcome (PICO) framework, these populations differ. It is important to examine these populations separately because the duration of RA, recency of active RA, and duration of remission may influence the success of TNFi discontinuation [12]. Previous reviews have not distinguished these different clinical scenarios, even though information on each group is needed for accurate patient counseling.

That about one-half of patients can successfully discontinue TNFi suggests that there may be subsets of patients with either higher or lower likelihoods of success. If these subsets could be identified, TNFi discontinuation could be more effectively targeted. The most consistent predictors of successful TNFi discontinuation have been the depth of remission and early RA [13]. Associations with other clinical features, particularly biomarkers, are less certain [12,13,14,15]. Whether predictors differ between patients stopping induction treatment or maintenance treatment is unknown.

Our goals were as follows: (1) to perform a systematic review of the prevalence of remission after TNFi discontinuation, separately in patients receiving induction therapy or stopping maintenance treatment, and (2) to perform a scoping review of predictors of remission in these two populations. We focused on TNFi discontinuation because this is currently the most common treatment de-escalation decision in RA [16].

Methods

We performed two related literature reviews: a systematic review of the prevalence of sustained remission/low disease activity (LDA) after discontinuation of TNFi treatment in patients with RA (and when available, comparison to continuation of TNFi), and a scoping review of predictors of continued remission/LDA after TNFi discontinuation [17]. We examined both questions following a written protocol, which was registered at the Center for Open Science (osf.oi/etzav). We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses 2020 recommendations (Supplement) [18].

Literature searches

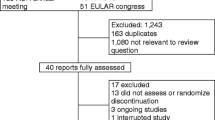

We searched five bibliographic databases for relevant studies in any language published from January 1, 2005, to May 1, 2022: PubMed/MEDLINE, Embase, Web of Science, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and Cochrane Reviews. We did not search before 2005 because discontinuation strategies were not used earlier. Search terms included “rheumatoid arthritis,” “tumor necrosis factor inhibitors,” individual medication names, “remission” or “low disease activity,” and “discontinuation” or “withdrawal” (Supplemental Table 1). We used EndNote20 for citation management. For the scoping review, one author also searched abstracts of congresses of the American College of Rheumatology and European League Against Rheumatism from 2010 to 2022 and Google through May 2023.

Study inclusion

Two authors independently reviewed the search results for relevant articles, first by title/abstract and subsequently full-text review. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion. We included full-length articles, reviews, conference abstracts, and trial registrations to identify primary articles and for the scoping review, but limited the systematic review to full-length articles. We included randomized controlled trials, single-arm trials, and observational studies that examined adults with RA who were in remission/LDA while on treatment with TNFi, and that reported patients’ remission status following discontinuation of TNFi treatment. We included articles regardless of the stringency of remission or RA activity index used, on the premise that investigators judged that RA activity was low enough that TNFi discontinuation was a reasonable consideration. Some studies had a controlled trial design to address a different primary question, but included TNFi discontinuation during follow-up as a secondary aim. We considered these as observational studies if TNFi discontinuation was not randomized.

We excluded cross-sectional studies, studies of other diseases or children or animals, case reports, letters, duplicate articles, and abstracts subsequently published as full-length articles. We also excluded studies of discontinuation of csDMARDs or other biologics unless the article included stratified data on TNFi. We excluded TNFi tapering studies and tapering arms of multi-arm trials (Supplemental Table 2). We focused on discontinuation rather than tapering, as tapering regimens vary, and discontinuation provides greater contrast to identify predictors. When more than one article was based on the same cohort, we included the article most relevant to the systematic or scoping review.

For the scoping review, we included full-length articles or conference abstracts that examined predictors of sustained remission/LDA after TNFi discontinuation. Predictors could be either clinical, imaging, or biological markers. We allowed studies that included patients who discontinued other biologics, provided that most patients used TNFi, and allowed studies that reported predictors of remission in the entire cohort (i.e., not limited to those who discontinued TNFi).

Data extraction

For the systematic review, two authors independently extracted data on RA activity at the time of TNFi discontinuation, remission/LDA criteria, prevalence of remission/LDA during follow-up, and outcomes of re-treatment, using a standardized format. Two authors also independently assessed study quality, using the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2 (ROB2) tool for controlled trials and the Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool for other studies [19, 20]. Results were compared and discrepancies resolved by discussion. For the scoping review, data on predictors and measures of association were extracted by one author and independently checked by a second author.

Statistical analysis

Our study outcome was the prevalence of remission/LDA after TNFi discontinuation. We pooled induction-withdrawal studies and maintenance discontinuation studies separately, and for each treatment strategy, we pooled the outcomes of Disease Activity Score 28 (DAS28) < 3.2, DAS28 < 2.6, or Simplified Disease Activity Index (SDAI) ≤ 3.3 separately. For the few studies that reported the outcome as the proportion that did not restart biologic treatment, we conservatively classified these as DAS28 < 3.2. Since relapses are time-dependent and more likely with longer follow-up, we pooled results reported at 24–36 weeks after discontinuation and 37–52 weeks after discontinuation separately. We computed pooled prevalences using restricted maximum likelihood estimation random effects models with the double arcsine transformation, using the metafor package in R (version 4.2.2). We used I2 to assess heterogeneity among studies. For studies that also provided data on sustained remission/LDA in patients who continued TNFi treatment, we pooled these results and computed relative risks and risk differences of remission/LDA between discontinuation and continuation arms, using random effects models implemented in OpenMeta (www.cebm.brown.edu/openmeta).

We analyzed predictors at the time of TNFi discontinuation by comparing patients who maintained remission/LDA or not, based on the remission/LDA criterion in each study. For continuous predictors, we used mean values to compute standardized mean differences (SMD) between the groups and pooled the SMDs using DerSimonian and Laird random effects models in OpenMeta. SMDs represent the number of standard deviations by which two groups differ, with positive values indicating higher means in patients with sustained remission. For studies reporting medians, we used the methods of McGrath to estimate means [21]. For categorical predictors, we computed odds ratios for remission/LDA from reported proportions, or used the study’s reported odds ratios, and pooled these using random effects models in OpenMeta. If only hazard ratios were reported, we pooled these separately. We harmonized the direction of associations across studies so that successful discontinuation was the outcome.

In sensitivity analyses, we excluded studies rated as high risk of bias with the ROB2 tool, or serious or critical risk of bias with the ROBINS-I tool.

Results

Search results

Of 3035 unique articles identified in electronic searches and 2077 articles screened from secondary sources, we included 43 articles in the systematic review of the prevalence of sustained remission/LDA after discontinuation and 37 studies in the scoping review of predictors (Fig. 1). Of the 43 articles in the systematic review, 22 articles reported induction-withdrawal studies and 22 articles reported studies of maintenance TNFi discontinuation, with 1 article including both groups [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64]. Data on predictors were reported in 12 induction-withdrawal articles [27, 33,34,35,36, 39, 41, 43, 65,66,67,68] and 22 maintenance discontinuation articles [44, 46, 47, 49,50,51,52, 54,55,56, 59,60,61,62, 64, 69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76].

Sustained remission/LDA in induction-withdrawal studies

These studies included 5 double-blind controlled trials [22,23,24,25,26], 1 open-label trial [27], and 16 studies in which TNFi discontinuation was observational [28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43] (Table 1 and Supplemental Table 3).

The criterion for TNFi discontinuation was DAS28 < 3.2 in 9 studies, DAS28 < 2.6 in 9 studies, and other indicators in 4 studies. The number of patients who discontinued TNFi ranged from 2 to 200 (median 34; total 1183), with larger samples in the trials. Seven studies examined etanercept, 5 examined infliximab, 5 examined adalimumab, 2 examined certolizumab, and 3 examined various TNFi. Follow-up varied from 24 to 96 weeks. Thirteen studies reported results at 37–52 weeks after TNFi discontinuation, and 6 studies reported results at 24–36 weeks. The proportion of patients with sustained remission/LDA after TNFi discontinuation varied widely (Table 1).

Remission prevalence after discontinuation

In the pooled analysis, 58% had DAS28 < 3.2 and 52% had DAS28 < 2.6 at 37–52 weeks after discontinuation, with high heterogeneity among studies (Fig. 2 and Supplemental table 4).

Pooled proportions having sustained remission/low disease activity at 37–52 weeks after either discontinuation or continuation of tumor necrosis factor inhibitor treatment in induction-withdrawal studies. Circles represent the DAS28 < 3.2 outcome, squares represent the DAS28 < 2.6 outcome, and triangles represent the SDAI ≤ 3.3 outcome. Closed symbols represent tumor necrosis factor inhibitor discontinuation arms, and open symbols represent continuation arms. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals

Only four studies reported SDAI-based results, and 40% of patients had SDAI ≤ 3.3 after discontinuation. The proportion remaining in remission/LDA was therefore lower with more stringent definitions of remission. At 24–36 weeks after TNFi discontinuation, 36% of patients maintained DAS28 < 3.2, 73% had DAS28 < 2.6, and 12% had SDAI ≤ 3.3 (Supplemental table 4).

Sensitivity analysis and study heterogeneity

The double-blind controlled trials were rated as having a low or moderate risk of bias, while the open-label trial was rated as having a high risk of bias (Supplemental Fig. 1). Seven observational studies were judged as having a serious risk of bias (Supplemental Fig. 2). In the sensitivity analysis, pooled results were similar when only studies with low or moderate risk of bias were examined (Fig. 2 and Supplemental table 4).

We explored potential heterogeneity by disease activity, duration of RA, and study design among the 9 studies that reported DAS28 < 2.6 outcomes at 37–52 weeks. Among the six studies that required DAS28 < 2.6 at the time of discontinuation [23, 27, 28, 32, 36, 39], the proportion with DAS28 < 2.6 at follow-up 1 year later was 58% (95% CI 33, 82), compared to 42% (95% CI 20, 67) among the three studies that required DAS28 < 3.2 at TNFi discontinuation [22, 24, 26] (p = 0.42). Among the six studies in early RA [22, 23, 26,27,28, 32], the pooled proportion with DAS28 < 2.6 at follow-up was 63% (95% CI 42, 82), compared to 32% (95% CI 17, 49) in three studies in established RA [24, 36, 39] (p = 0.05). Among the five controlled trials [22,23,24, 26, 27], the pooled prevalence with DAS28 < 2.6 at follow-up was 47% (95% CI 30, 63), while among the four observational studies [28, 32, 36, 39], the pooled prevalence was 58% (95% CI 25, 88) (p = 0.84).

Retreatment

In five studies that reported on retreatment (64 patients combined) after relapse following TNFi discontinuation, 96% (95% CI 85, 100) regained remission/LDA after resuming TNFi treatment (Supplemental Table 3).

Remission prevalence with TNFi continuation in controlled studies

In the controlled studies, 85%, 73%, and 62% of patients who continued TNFi treatment maintained DAS28 < 3.2, DAS28 < 2.6, and SDAI ≤ 3.3, respectively, at 37–52 weeks’ follow-up (Fig. 2 and Supplemental table 4). In pooled analyses of controlled studies that compared those who discontinued TNFi to those who continued TNFi, the risk ratio of sustained DAS28 < 3.2 was 0.69, the risk ratio of sustained DAS28 < 2.6 was 0.58, and the risk ratio of sustained SDAI ≤ 3.3 was 0.59 (Supplemental table 5). Pooled risk differences were − 22.2%, − 27.3%, and − 18.4% for these outcomes, indicating that absolute relapses in the discontinuation group exceeded those in the paired continuation group by these amounts.

Sustained remission/LDA after discontinuation of maintenance TNFi

These studies included 3 double-blind controlled trials [44,45,46], 2 open-label trials [47, 48], and 17 studies in which TNFi discontinuation was observational [33, 49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64], including 4 registry studies [54, 55, 62, 63] (Table 2 and Supplemental table 6).

Six studies used DAS28 < 3.2 as the criterion for discontinuation, 9 studies used DAS28 < 2.6, 2 studies used SDAI ≤ 3.3, and 5 studies used other criteria. Thirteen studies included patients treated with different TNFi. Minimum durations of remission/LDA were 3 months in 3 studies, 6 months in 9 studies, longer than 6 months in 3 studies, and unspecified in 7 studies. The number of patients who discontinued TNFi ranged from 4 to 717 (median 30; total 2142). Five studies reported outcomes at 24–36 weeks, 14 studies reported results at 37–52 weeks, and 3 studies reported outcomes at longer times.

Remission prevalence after discontinuation

In the pooled results, 48% of patients had DAS28 < 3.2 at 37–52 weeks after discontinuation, 47% had DAS28 < 2.6, and 46% had SDAI ≤ 3.3, with high heterogeneity among studies (Fig. 3 and Supplemental table 7). At 24–36 weeks after TNFi discontinuation, 85% of patients maintained DAS28 < 3.2, and 75% had DAS28 < 2.6.

Pooled proportions having sustained remission/low disease activity at 37–52 weeks after either discontinuation or continuation of tumor necrosis factor inhibitor treatment in maintenance discontinuation studies. Circles represent the DAS28 < 3.2 outcome, squares represent the DAS28 < 2.6 outcome, and triangles represent the SDAI ≤ 3.3 outcome. Closed symbols represent tumor necrosis factor inhibitor discontinuation arms, and open symbols represent continuation arms

The blinded trials were rated as having a low or moderate risk of bias, while the open-label trials had high risk of bias (Supplemental Fig. 3). Nine observational studies were rated as having a low or moderate risk of bias (Supplemental Fig. 4).

Sensitivity analysis and study heterogeneity

In the sensitivity analysis, the proportions of patients with successful discontinuation among studies with low or moderate risk of bias were similar to, or somewhat lower than, the proportions among all studies (Fig. 3 and Supplemental table 7).

Examining heterogeneity by RA activity, DAS28 < 2.6 at 37–52 weeks after discontinuation was only slightly more common among studies that required DAS28 < 2.6 at enrollment [52, 57, 60] compared to studies that required DAS28 < 3.2 at enrollment [48, 50, 59] (53% (95% CI 38, 68) versus 45% (95% CI 25, 67)). All studies of maintenance treatment discontinuation examined patients with established RA. The proportion with DAS28 < 2.6 at follow-up was higher in the five observational studies [50, 52, 57, 59, 60] (53%; 95% CI 40, 66) than in the one clinical trial [48] (29%; 95% CI 25, 34) (p = 0.04).

Retreatment

Among 11 studies that reported on retreatment of relapses (360 patients combined), the pooled proportion of patients who regained remission was 86% (95% CI 71, 98) (Supplemental table 6).

Remission prevalence with TNFi continuation in controlled studies

Among patients in controlled studies who continued TNFi, 69% maintained DAS28 < 3.2, 64% maintained DAS28 < 2.6, and 53% maintained SDAI ≤ 3.3 at 37–52 weeks, although the number of studies was small (Fig. 3 and Supplemental table 7). In paired analyses of studies that reported both discontinuation and continuation arms, sustained remission/LDA was more likely among those who continued TNFi, with risk ratios that ranged from 0.47 to 0.57 (Supplemental table 8). Risk differences indicated that absolute rates of maintaining DAS28 < 3.2 were, on average, 33.4% lower with discontinuation, and of maintaining DAS28 < 2.6 were 32.1% lower with discontinuation.

Predictors of successful discontinuation in induction-withdrawal studies

Collectively, data on 18 different predictors were reported (Table 3 and Supplemental table 9) [27, 33,34,35,36, 39, 41, 43, 65,66,67,68]. However, only 8 predictors were reported by more than 3 studies, and pooling was limited because studies used different effect size measures. Older age was not predictive in studies that reported mean ages, but older age groups were less likely to have successful discontinuation in two studies that reported odds ratios [43, 65]. Mean duration of RA was shorter among patients with successful discontinuation. Longer duration of TNFi treatment prior to discontinuation was associated with lower likelihood of success.

Human leukocyte antigen (HLA) shared epitope, radiographic damage, and smoking were associated with a lower likelihood of successful discontinuation, based on one study [66]. Mean Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) scores and mean disease activity scores were lower among patients with successful discontinuation. There were no associations with other predictors, including sex, seropositivity, and ultrasound measures. Serum matrix metalloproteinase-3 did not predict relapse in one study [39], while relapses were associated with lower proportions of peripheral blood naïve T cells and higher proportions of regulatory T cells in another study [33].

Few induction-withdrawal studies with low or moderate risk of bias reported on predictors (Supplemental table 10). Duration of RA was not clearly predictive in this subset.

Predictors of successful discontinuation of maintenance TNFi treatment

More information was available among these studies, with data on 17 predictors reported in more than 3 studies (Table 3 and Supplemental table 9) [44, 46, 47, 49,50,51,52, 54,55,56, 59,60,61,62, 64, 69,70,71,72,73,74,75]. Mean duration of RA was shorter among patients with successful discontinuation, as was a shorter time to reach remission with TNFi treatment [55]. Patients treated with monoclonal TNFi tended to have more successful discontinuation than those receiving etanercept. Patients with more radiographic damage and obese patients were less likely to have successful discontinuation. Smoking, higher HAQ scores, and higher disease activity were associated with lower likelihoods of successful discontinuation only in two registry studies that reported hazard ratios [54, 55]. Higher multi-biomarker disease activity score was associated with lower odds of successful discontinuation in one study [69]. There were no associations with other variables, including length of remission, seropositivity, and ultrasound measures.

Selected laboratory biomarkers were examined in individual studies. Among 12 serum cytokines or cytokine receptors, lower levels of interleukin-2 and higher levels of soluble TNF receptor 1 at baseline predicted flare after treatment discontinuation in a small cohort [61]. Nagatani reported that relapse was associated with high serum interleukin-34, chemokine ligand-1, and interleukin-1β, and low serum interleukin-19 and interleukin-2 [64]. A low proportion of MerTK+CD206+ synovial tissue macrophages was strongly associated with the risk of flare after TNFi discontinuation [76].

Among studies with low or moderate risk of bias, successful discontinuation was less likely among patients with longer durations of RA and more radiographic damage, but was not associated with other clinical variables (Supplemental table 10).

Discussion

Discontinuation of TNFi treatment in patients with well-controlled RA has the potential to improve care by simplifying regimens, decreasing treatment-related side effects, and reducing costs, but comes with the risk of increased RA activity. Knowing the absolute risk of relapse is needed to inform decision-making. Because these risks, and the associated strength of evidence, may differ between short-term TNFi treatment in an induction-withdrawal strategy and discontinuation of long-term maintenance TNFi treatment, it is important to examine these risks separately. Our pooled results indicated that 58% of patients had DAS28 < 3.2 and 52% had DAS28 < 2.6 at approximately 1 year after withdrawal of induction treatment. Comparable proportions were 48% and 47% after discontinuation of maintenance TNFi treatment. Few studies reported SDAI remission or results at 24–36 weeks.

Two previous systematic reviews that included 16 and 12 studies, respectively, reported successful discontinuation in 53% and 62% of patients [7, 77]. However, these reviews pooled studies that had different criteria for remission and different lengths of follow-up, and did not distinguish between the two clinical scenarios of discontinuation, limiting the specificity of their results. These results were comparable to our findings in induction-withdrawal studies, but were higher than our results for maintenance discontinuation studies. Successful discontinuation was more common in induction-withdrawal studies, which may reflect greater responsiveness in early RA. The proportion with successful discontinuation also decreased with increasing stringency of remission, particularly so for SDAI ≤ 3.3. Stratifying by the timing of responses is also important because more relapses would be expected with longer follow-up. In maintenance discontinuation studies, for example, DAS28 < 2.6 was maintained by 75% at 24–36 weeks but only 47% at 37–52 weeks. We did not observe a similar pattern in the induction-withdrawal studies, although few studies reported results at early times. These observations underscore differences by clinical scenario, outcome, and time.

Other reviews summarized discontinuation studies qualitatively [4, 8, 9, 12, 78,79,80] or included only controlled trials and focused on comparisons between discontinuation and continuation of TNFi [10, 11, 81,82,83]. In these meta-analyses, risk ratios for LDA with discontinuation ranged from 0.44 to 0.75, and risk ratios for DAS28 remission ranged from 0.45 to 0.71 [10, 80,81,82]. We focused on the absolute risks associated with discontinuation, because absolute frequencies of relapse are an important consideration in individual patient decision-making. Data on patients who continued TNFi treatment showed that, on average, 15% of patients did not maintain LDA and 27% did not maintain DAS28 remission for periods up to 1 year in induction studies, while 31% and 36% of patients who continued maintenance TNFi treatment similarly relapsed. These results provide useful context for interpreting the proportions in the discontinuation arms, highlighting that not all these relapses are necessarily attributable to TNFi discontinuation. Many would have been expected regardless of TNFi discontinuation. Risk differences assess this directly and indicate that relapses attributable to discontinuation ranged from 20 to 33%.

It is important to note that there was substantial heterogeneity among studies, even with the same design, outcome, and length of follow-up. This may be due to differences in inclusion criteria, patient selection, and depth of remission. That 15–47% of patients lose remission over 1 year despite continuing on TNFi treatment may be due to the limited specificity of these remission criteria, but also indicates that remission in RA does not indicate a cure.

Among induction-withdrawal studies, TNFi discontinuation was more successful in patients with early RA, approaching the prevalence seen in those who continued TNFi (63% versus 73%). Greater success in early RA and among patients with deeper remission has been suggested previously [13, 14, 78, 84]. In our pooled analysis, associations with a shorter duration of RA and lower disease activity were also supported by multiple studies, as were lower HAQ scores and shorter duration of TNFi treatment. RA activity and HAQ were not found to be associated with successful discontinuation in studies that dichotomized these measures, perhaps due to reduced statistical power. Age, sex, seropositivity, and methotrexate dose were not predictive of successful discontinuation in induction-withdrawal studies. There were few data on other predictors.

Among studies of maintenance TNFi treatment, discontinuation was more successful among patients with shorter RA durations and less radiographic damage, as identified previously [14]. Given that radiographic changes are cumulative, it is not clear if radiographic damage predicts the risk of relapse independent of RA duration. Shorter time to remission with TNFi treatment was also associated with successful discontinuation. Interestingly, monoclonal TNFi tended to have more successful discontinuation than etanercept. Whether this is related to patient selection or different immunological effects is unclear. We found no association with other clinical variables, including disease activity, in contrast to induction-withdrawal studies [14].

Few studies examined immunological biomarkers, and it is difficult to draw conclusions about prognostic importance based on single studies. Given the general absence of clinical predictors, it may be that immunological markers will be key to identifying which patients will be able to maintain remission after TNFi discontinuation. Although subclinical joint inflammation is common in clinical remission [85], our results did not support the prognostic value of ultrasound in studies of TNFi discontinuation. Power Doppler positivity in remission has been associated with higher odds of relapse in one study, but this study did not examine treatment discontinuation [85]. In three studies of biologic tapering, ultrasound abnormalities predicted relapse, indicating that further evaluation of the potential prognostic value of ultrasound is warranted [86,87,88]. Subclinical joint inflammation by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has also been observed in many patients in clinical remission, but MRI has not been found to predict relapses on biologic tapering [45, 88, 89]. We did not identify prognostic studies of MRI in the setting of TNFi discontinuation.

Our study is limited by the definitions of remission used in the primary studies, which may be considered too liberal. Few studies used SDAI remission as either the inclusion criterion or outcome, and none used American College of Rheumatology Boolean criteria. Interestingly, the more stringent SDAI criterion resulted in both lower proportions of remission and higher proportions of relapses, reflecting increased difficulty of maintaining this level of RA activity over time. We focused on TNFi discontinuation, given there are few discontinuation studies of other biologics or csDMARDs, or of tapering, and pooling results of different strategies or medications would decrease the specificity of any conclusions. We included both observational studies and controlled trials. Although several studies were judged to have a high risk of bias, results were generally similar after excluding such studies. Pooling of results in the predictor analysis was limited by the diversity of effect measures in the primary studies. We cannot exclude the possibility of publication bias, which is difficult to identify in the presence of heterogeneity [90]. We tried to minimize publication bias by using a comprehensive search strategy that included trial registrations, abstracts, and no language restrictions. We also included articles whose main objective was not to determine the prevalence of remission after TNFi discontinuation.

Conclusions

This study is the first to examine the outcomes of TNFi discontinuation separately in induction treatment and maintenance treatment. Almost one-half of patients were able to discontinue maintenance TNFi treatment and remain in remission for up to 1 year. More patients had successful discontinuation in induction-withdrawal studies, underscoring the differences in outcomes between these scenarios. In both cases, patients with early RA were more likely to have successful discontinuation. After induction treatment with TNFi, approximately 6 in 10 patients with early RA would remain in remission for up to 1 year after discontinuation, but only 3 in 10 patients with established RA would do so. After discontinuation of maintenance TNFi treatment, approximately 5 in 10 patients would remain in remission for up to 1 year. These results may be useful in shared decision-making with patients who are contemplating treatment de-escalation. More research is needed to identify how risks of relapse vary in patient subgroups.

Availability of data and materials

All data were obtained from publicly available materials, and all data are included in the article or Supplement.

Abbreviations

- ACPA:

-

Anti-citrullinated protein antibody

- ADA:

-

Adalimumab

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CDAI:

-

Clinical disease activity index

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- CTZ:

-

Certolizumab

- csDMARDs:

-

Conventional synthetic disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs

- DAS28:

-

Disease activity score 28

- ESR:

-

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- ETA:

-

Etanercept

- GOL:

-

Golimumab

- HAQ:

-

Health assessment questionnaire

- HLA:

-

Human leukocyte antigen

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- INF:

-

Infliximab

- LDA:

-

Low disease activity

- MBDA:

-

Multi-biomarker disease activity score

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- PICO:

-

Population intervention comparator outcome

- RA:

-

Rheumatoid arthritis

- RADAI:

-

Rheumatoid arthritis disease activity index

- RF:

-

Rheumatoid factor

- ROB2:

-

Risk of bias 2

- ROBINS-I:

-

Risk of bias in non-randomized studies of interventions

- SDAI:

-

Simplified disease activity index

- SMD:

-

Standardized mean difference

- TNFi:

-

Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors

References

Westerlind H, Glintborg B, Hammer HB, et al. Remission, response, retention and persistence to treatment with disease-modifying agents in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a study of harmonised Swedish, Danish and Norwegian cohorts. RMD Open. 2023;9:e003027. https://doi.org/10.1136/rmdopen-2023-003027.

Aga AB, Lie E, Uhlig T, et al. Time trends in disease activity, response and remission rates in rheumatoid arthritis during the past decade: results from the NOR-DMARD study 2000–2010. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:381–8.

Feist E, Baraliakos X, Behrens F, et al. Effectiveness of etanercept in rheumatoid arthritis: real-world data from the German non-interventional study ADEQUATE with focus on treat-to-target and patient-reported outcomes. Rheumatol Ther. 2022;9:621–35.

Fautrel B, Den Broeder AA. De-intensifying treatment in established rheumatoid arthritis (RA): why, how, when and in whom can DMARDs be tapered? Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2015;29:550–65.

Bolge SC, Goren A, Tandon N. Reasons for discontinuation of subcutaneous biologic therapy in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: a patient perspective. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2015;9:121–31.

Donovan JL, Blake DR. Patient non-compliance: deviance or reasoned decision-making? Soc Sci Med. 1992;34:507–13.

Mangoni AA, Al Okaily F, Almoallim H, et al. Relapse rates after elective discontinuation of anti-TNF therapy in rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis and review of literature. BMC Rheumatol. 2019;8(3):10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41927-019-0058-7.

Verhoef LM, Tweehuysen L, Hulscher ME, et al. bDMARD dose reduction in rheumatoid arthritis: a narrative review with systematic literature search. Rheumatol Ther. 2017;4:1–24.

Ruscitti P, Sinigaglia L, Cazzato M, et al. Dose adjustments and discontinuation in TNF inhibitors treated patients: when and how. A systematic review of literature. Rheumatology. 2018;57(Suppl 7):vii23–31.

Henaux S, Ruyssen-Witrand A, Cantagrel A, et al. Risk of losing remission, low disease activity or radiographic progression in case of bDMARD discontinuation or tapering in rheumatoid arthritis: systematic analysis of the literature and meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77:515–22.

Verhoef LM, van den Bemt BJ, van der Maas A, et al. Down-titration and discontinuation strategies of tumour necrosis factor-blocking agents for rheumatoid arthritis in patients with low disease activity. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;5(5):CD010455. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD010455.pub3.

Schett G, Emery P, Tanaka Y, et al. Tapering biologic and conventional DMARD therapy in rheumatoid arthritis: current evidence and future directions. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:1428–37.

Schlager L, Loiskandl M, Aletaha D, et al. Predictors of successful discontinuation of biologic and targeted synthetic DMARDs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in remission or low disease activity: a systematic literature review. Rheumatology. 2020;59:324–34.

Tweehuysen L, van den Ende CH, Beeren FM, et al. Little evidence for usefulness of biomarkers for predicting successful dose reduction or discontinuation of a biologic agent in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69:301–8.

Johnson TM, Register KA, Schmidt CM, et al. Correlation of the multi-biomarker disease activity score with rheumatoid arthritis disease activity measures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Care Res. 2019;71:1459–72.

Smolen JS, Landewé RBM, Bijlsma JWJ, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2019 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79:685–99.

Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, et al. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18:143. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2021;134:178–89.

Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l4898.

Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355:i4919. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i4919.

McGrath S, Zhao X, Steele R, et al. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from commonly reported quantiles in meta-analysis. Stat Methods Med Res. 2020;29:2520–37.

Smolen JS, Emery P, Fleischmann R, et al. Adjustment of therapy in rheumatoid arthritis on the basis of achievement of stable low disease activity with adalimumab plus methotrexate or methotrexate alone: the randomised controlled OPTIMA trial. Lancet. 2014;383:321–32.

Emery P, Hammoudeh M, FitzGerald O, et al. Sustained remission with etanercept tapering in early rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1781–92.

Smolen JS, Nash P, Durez P, et al. Maintenance, reduction, or withdrawal of etanercept after treatment with etanercept and methotrexate in patients with moderate rheumatoid arthritis (PRESERVE): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2013;381:918–29.

Pavelka K, Akkoç N, Al-Maini M, et al. Maintenance of remission with combination etanercept–DMARD therapy versus DMARDs alone in active rheumatoid arthritis: results of an international treat-to-target study conducted in regions with limited biologic access. Rheumatol Int. 2017;37:1469–79.

Weinblatt ME, Bingham CO III, Burmester GR, et al. A phase III study evaluating continuation, tapering, and withdrawal of certolizumab pegol after one year of therapy in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69:1937–48.

Yamanaka H, Nagaoka S, Lee SK, et al. Discontinuation of etanercept after achievement of sustained remission in patients with rheumatoid arthritis who initially had moderate disease activity—results from the ENCOURAGE study, a prospective, international, multicenter randomized study. Mod Rheumatol. 2016;26:651–61.

Quinn MA, Conaghan PG, O’Connor PJ, et al. Very early treatment with infliximab in addition to methotrexate in early, poor-prognosis rheumatoid arthritis reduces magnetic resonance imaging evidence of synovitis and damage, with sustained benefit after infliximab withdrawal: results from a twelve-month randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:27–35.

Van der Bijl AE, Goekoop-Ruiterman YP, de Vries-Bouwstra JK, et al. Infliximab and methotrexate as induction therapy in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:2129–34.

Nawata M, Saito K, Nakayamada S, et al. Discontinuation of infliximab in rheumatoid arthritis patients in clinical remission. Mod Rheumatol. 2008;18:460–4.

Soubrier M, Puéchal X, Sibilia J, et al. Evaluation of two strategies (initial methotrexate monotherapy vs its combination with adalimumab) in management of early active rheumatoid arthritis: data from the GUEPARD trial. Rheumatology. 2009;48:1429–34.

Laganà B, Picchianti Diamanti A, Ferlito C, et al. Imaging progression despite clinical remission in early rheumatoid arthritis patients after etanercept interruption. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2009;22:447–54.

Saleem B, Keen H, Goeb V, et al. Patients with RA in remission on TNF blockers: when and in whom can TNF blocker therapy be stopped? Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:1636–42.

Migliore A, Bizzi E, Massafra U, et al. Can cyclosporine-A associated to methotrexate maintain remission induced by anti-TNF agents in rheumatoid arthritis patients? (CYNAR pilot study). Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2010;23:783–90.

Migliore A, Bizzi E, Massafra U, et al. A new chance to maintain remission induced by anti-TNF agents in rheumatoid arthritis patients: CynAR study II of a 12-month follow-up. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2011;24:167–74.

Harigai M, Takeuchi T, Tanaka Y, et al. Discontinuation of adalimumab treatment in rheumatoid arthritis patients after achieving low disease activity. Mod Rheumatol. 2012;22:814–22.

Nam JL, Villeneuve E, Hensor EM, et al. Remission induction comparing infliximab and high-dose intravenous steroid, followed by treat-to-target: a double-blind, randomised, controlled trial in new-onset, treatment-naive, rheumatoid arthritis (the IDEA study). Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:75–85.

Nam JL, Villeneuve E, Hensor EM, et al. A randomised controlled trial of etanercept and methotrexate to induce remission in early inflammatory arthritis: the EMPIRE trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:1027–36.

Tanaka Y, Hirata S, Kubo S, et al. Discontinuation of adalimumab after achieving remission in patients with established rheumatoid arthritis: 1-year outcome of the HONOR study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:389–95.

Smolen JS, Emery P, Ferraccioli GF, et al. Certolizumab pegol in rheumatoid arthritis patients with low to moderate activity: the CERTAIN double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:843–50.

Tanaka Y, Yamanaka H, Ishiguro N, et al. Adalimumab discontinuation in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis who were initially treated with methotrexate alone or in combination with adalimumab: 1 year outcomes of the HOPEFUL-2 study. RMD Open. 2016;2:e000189. https://doi.org/10.1136/rmdopen-2015-000189.

Inui K, Koike T, Tada M, et al. Clinical and radiologic analysis of on-demand use of etanercept for disease flares in patients with rheumatoid arthritis for 2 years: The RESUME study: a case-control study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e12462. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000012462.

Tanaka Y, Oba K, Koike T, et al. Sustained discontinuation of infliximab with a raising-dose strategy after obtaining remission in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: the RRRR study, a randomised controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79:94–102.

van Vollenhoven RF, Østergaard M, Leirisalo-Repo M, et al. Full dose, reduced dose or discontinuation of etanercept in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:52–8.

Emery P, Burmester GR, Naredo E, et al. Adalimumab dose tapering in patients with rheumatoid arthritis who are in long-standing clinical remission: results of the phase IV PREDICTRA study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79:1023–30.

Curtis JR, Emery P, Karis E, et al. Etanercept or methotrexate withdrawal in rheumatoid arthritis patients in sustained remission. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021;73:759–68.

Chatzidionysiou K, Turesson C, Teleman A, et al. A multicentre, randomised, controlled, open-label pilot study on the feasibility of discontinuation of adalimumab in established patients with rheumatoid arthritis in stable clinical remission. [ADMIRE] RMD Open. 2016;2:e000133. https://doi.org/10.1136/rmdopen-2015-000133.

Ghiti Moghadam M, Vonkeman HE, Ten Klooster PM, et al. Stopping tumor necrosis factor inhibitor treatment in patients with established rheumatoid arthritis in remission or with stable low disease activity: a pragmatic multicenter, open-label randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68:1810–7.

Brocq O, Millasseau E, Albert C, et al. Effect of discontinuing TNFα antagonist therapy in patients with remission of rheumatoid arthritis. Joint Bone Spine. 2009;76:350–5.

Tanaka Y, Takeuchi T, Mimori T, et al. Discontinuation of infliximab after attaining low disease activity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: RRR (remission induction by Remicade in RA) study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:1286–91.

Iwamoto T, Ikeda K, Hosokawa J, et al. Prediction of relapse after discontinuation of biologic agents by ultrasonographic assessment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in clinical remission: High predictive values of total gray-scale and power Doppler scores that represent residual synovial inflammation before discontinuation. Arthritis Care Res. 2014;66:1576–81.

Kurasawa T, Nagasawa H, Kishimoto M, et al. Addition of another disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug to methotrexate reduces the flare rate within 2 years after infliximab discontinuation in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: an open, randomized, controlled trial. Mod Rheumatol. 2014;24:561–6.

Kádár G, Balázs E, Soós B, et al. Disease activity after the discontinuation of biological therapy in inflammatory rheumatic diseases. Clin Rheumatol. 2014;33:329–33.

Kavanaugh A, Lee SJ, Curtis JR, et al. Discontinuation of tumour necrosis factor inhibitors in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in low-disease activity: persistent benefits. Data from the Corrona registry. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:1150–5.

Yoshida K, Kishimoto M, Radner H, et al. Low rates of biologic-free clinical disease activity index remission maintenance after biologic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug discontinuation while in remission in a Japanese multicentre rheumatoid arthritis registry. Rheumatology. 2016;55:286–90.

Kawashiri SY, Fujikawa K, Nishino A, et al. Ultrasound-detected bone erosion is a relapse risk factor after discontinuation of biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis whose ultrasound power Doppler synovitis activity and clinical disease activity are well controlled. Arthritis Res Ther. 2017;19:108. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-017-1320-2.

Kimura N, Suzuki K, Takeuchi T. Demographics and clinical characteristics associated with sustained remission and continuation of sustained remission in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with adalimumab. Inflamm Regen. 2019;39:5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41232-019-0094-0.

Ito S, Kobayashi D, Hasegawa E, et al. An analysis of the biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drug-free condition of adalimumab-treated rheumatoid arthritis patients. Intern Med. 2019;58:511–9.

Naniwa T, Iwagaitsu S, Kajiura M. Successful cessation of tumor necrosis factor inhibitor treatment in rheumatoid arthritis patients and potential predictors for early flare: an observational study in routine clinical care. Mod Rheumatol. 2020;30:948–58.

Takai C, Ito S, Kobayashi D, et al. Two-year outcomes of infliximab discontinuation in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a retrospective analysis from a single center. Intern Med. 2020;59:1963–70.

Kameda H, Hirata A, Katagiri T, et al. Prediction of disease flare by biomarkers after discontinuing biologics in patients with rheumatoid arthritis achieving stringent remission. Sci Rep. 2021;11:6865. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-86335-7.

Ochiai M, Tanaka E, Sato E, et al. Successful discontinuation of biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in real-world settings. Mod Rheumatol. 2021;31:790–5.

Burkard T, Williams RD, Vallejo-Yague E, et al. Prediction of sustained biologic and targeted synthetic DMARD-free remission in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Rheumatol Adv Pract. 2021;13(5):rkab087. https://doi.org/10.1093/rap/rkab087.

Nagatani K, Sakashita E, Endo H, et al. A novel multi-biomarker combination predicting relapse from long-term remission after discontinuation of biological drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. Sci Rep. 2021;11:20771. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-00357-9.

Emery P, Pedersen R, Bukowski J, et al. Predictors of remission maintenance after etanercept tapering or withdrawal in early rheumatoid arthritis: results from the PRIZE study. Open Rheumatol J. 2018;12:179–88.

Van den Broek M, Klarenbeek NB, Dirven L, et al. Discontinuation of infliximab and potential predictors of persistent low disease activity in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis and disease activity score-steered therapy: subanalysis of the BeSt study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:1389–94.

Smolen JS, Szumski A, Koenig AS, et al. Predictors of remission with etanercept-methotrexate induction therapy and loss of remission with etanercept maintenance, reduction, or withdrawal in moderately active rheumatoid arthritis: results of the PRESERVE trial. Arthritis Res Ther. 2018;20:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-017-1484-9.

Hirata S, Wang X, Hwang CC, et al. Predicting flare and sustained clinical remission after adalimumab withdrawal using the multi-biomarker disease activity (MBDA) score [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(Suppl):3564–5.

Ghiti Moghadam M, Lamers-Karnebeek FBG, Vonkeman HE, et al. Predictors of biologic-free disease control in patients with rheumatoid arthritis after stopping tumor necrosis factor inhibitor treatment. BMC Rheumatol. 2019;3:3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41927-019-0071-x.

Lurati A, Scarpellini M, Angela K, et al. Biologic free remission rate with etanercept in rheumatoid arthritis: a potential role of gender [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(Suppl 9):827–8.

Curtis J, Emery P, Haraoui B, et al. Low patient global assessment of disease activity and negative rheumatoid factor are strongly associated with likelihood of maintaining remission following tapering of therapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021;73(Suppl 9):2556–8.

Okano T, Hara R, Wada M, et al. Prediction of recurrence after discontinuation of adalimumab by using ultrasound assessment -the PROUD study [abstract]. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-eular.4315.

Amano K, Aoki K, Kuga Y, et al. Prospective study of bio-free remission maintenance using ultrasonography in rheumatoid arthritis patients: 52-week result [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69(Suppl 10). https://acrabstracts.org/abstract/prospective-study-of-bio-free-remission-maintenance-using-ultrasonography-in-rheumatoid-arthritis-patients-52-week-result/.

Lo Monaco A, Scirè CA, Casciano F, et al. Frequency of disease flare and study of the CD4+CD25+highCD127low/- cell populations after discontinuation of anti-tnfa therapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in persistent remission [abstract]. Ann Rheu Dis. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-eular.5102.

Lamers-Karnebeek FB, Luime JJ, Ten Cate DF, et al. Limited value for ultrasonography in predicting flare in rheumatoid arthritis patients with low disease activity stopping TNF inhibitors. Rheumatology. 2017;56:1560–5.

Alivernini S, MacDonald L, Elmesmari A, et al. Distinct synovial tissue macrophage subsets regulate inflammation and remission in rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Med. 2020;26:1295–306.

Kuijper TM, Lamers-Karnebeek FB, Jacobs JW, et al. Flare rate in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in low disease activity or remission when tapering or stopping synthetic or biologic dmard: a systematic review. J Rheumatol. 2015;42:2012–22.

Navarro-Millán I, Sattui SE, Curtis JR. Systematic review of tumor necrosis factor inhibitor discontinuation studies in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Ther. 2013;35:1850–61.

Nam JL, Takase-Minegishi K, Ramiro S, et al. Efficacy of biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: a systematic literature review informing the 2016 update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:1113–36.

Lenert A, Lenert P. Tapering biologics in rheumatoid arthritis: a pragmatic approach for clinical practice. Clin Rheumatol. 2017;36:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-016-3490-8.

Uhrenholt L, Christensen R, Dinesen WKH, et al. Risk of flare after tapering or withdrawal of biologic/targeted synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis or axial spondyloarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatology. 2022;61:3107–22.

Vasconcelos LB, Silva MT, Galvao TF. Reduction of biologics in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatol Int. 2020;40:1949–59.

Emamikia S, Arkema EV, Györi N, et al. Induction maintenance with tumour necrosis factor-inhibitor combination therapy with discontinuation versus methotrexate monotherapy in early rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of efficacy in randomised controlled trials. RMD Open. 2016;2:e000323. https://doi.org/10.1136/rmdopen-2016-000323.

Tanaka Y, Smolen JS, Jones H, et al. The effect of deep or sustained remission on maintenance of remission after dose reduction or withdrawal of etanercept in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2019;21:164. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-019-1937-4.

Nguyen H, Ruyssen-Witrand A, Gandjbakhch F, et al. Prevalence of ultrasound-detected residual synovitis and risk of relapse and structural progression in rheumatoid arthritis patients in clinical remission: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatology. 2014;53:2110–8.

Naredo E, Valor L, De la Torre I, et al. Predictive value of Doppler ultrasound-detected synovitis in relation to failed tapering of biologic therapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology. 2015;54:1408–14.

Alivernini S, Peluso G, Fedele AL, et al. Tapering and discontinuation of TNF-α blockers without disease relapse using ultrasonography as a tool to identify patients with rheumatoid arthritis in clinical and histological remission. Arthritis Res Ther. 2016;18:39. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-016-0927-z.

Terslev L, Brahe CH, Hetland ML, et al. Doppler ultrasound predicts successful discontinuation of biological DMARDs in rheumatoid arthritis patients in clinical remission. Rheumatology. 2021;60:5549–59.

Gandjbakhch F, Conaghan PG, Ejbjerg B, et al. Synovitis and osteitis are very frequent in rheumatoid arthritis clinical remission: results from an MRI study of 294 patients in clinical remission or low disease activity state. J Rheumatol. 2011;38:2039–44.

Ioannidis JP, Trikalinos TA. The appropriateness of asymmetry tests for publication bias in meta-analyses: a large survey. CMAJ. 2007;176:1091–6.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) M. Ward was funded by the Intramural Research Program, National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, NIH, which had no role in the conceptualization, design, analysis, or decision to publish this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors collected the data. MW and AY did the analysis. MW wrote the main manuscript text and prepared the figures. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Authors’ information

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy of the NIH or US government.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This work does not involve research on human subjects and based on U.S. 45CRF46 is exempt from ethics board review.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Supplemental table 1.

Database search terms. Supplemental table 2. Studies commonly cited but excluded from this review. Supplemental table 3. Detailed characteristics of induction withdrawal studies. Supplemental table 4. Pooled proportions of patients having sustained remission/low disease activity after either discontinuation or continuation of tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi) treatment in induction-withdrawal studies, stratified by length of follow-up. Supplemental figure 1. Risk of bias evaluation of controlled trials among induction-withdrawal studies of tumor necrosis factor inhibitors using the Risk of Bias-2 tool. Supplemental figure 2. Risk of bias evaluation of observational studies of induction-withdrawal of tumor necrosis factor inhibitor treatment using the Risk of Bias in Non-randomised Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool. Supplemental table 5. Relative risks and risk differences of sustained remission/low disease activity with discontinuation versus continuation of tumor necrosis factor inhibitor treatment in induction-withdrawal studies that reported both arms. Supplemental table 6. Detailed characteristics of studies of discontinuation of maintenance treatment with tumor necrosis factor inhibitors. Supplemental table 7. Pooled proportions of patients having sustained remission/low disease activity after either discontinuation or continuation of maintenance treatment with tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi), stratified by length of follow-up. Supplemental figure 3. Risk of bias evaluation of controlled trials of discontinuation of maintenance treatment with tumor necrosis factor inhibitors using the Risk of Bias-2 tool. Supplemental figure 4. Risk of bias evaluation in observational studies of discontinuation of maintenance treatment with tumor necrosis factor inhibitors, using the Risk of Bias In Non-randomised Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-1) tool. Supplemental table 8. Relative risks and risk differences of sustained remission or low disease activity with discontinuation versus continuation of tumor necrosis factor inhibitor treatment in maintenance discontinuation studies that reported both arms. Supplemental table 9. Predictors of successful discontinuation, by study. Supplemental table 10. Predictors of sustained remission in studies of discontinuation of tumor necrosis factor inhibitor treatment among studies of low or moderate risk of bias. PRISMA checklist.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Ward, M.M., Madanchi, N., Yazdanyar, A. et al. Prevalence and predictors of sustained remission/low disease activity after discontinuation of induction or maintenance treatment with tumor necrosis factor inhibitors in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic and scoping review. Arthritis Res Ther 25, 222 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-023-03199-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-023-03199-0