Abstract

Background

Tsetse control is considered an effective and sustainable tactic for the control of cyclically transmitted trypanosomosis in the absence of effective vaccines and inexpensive, effective drugs. The sterile insect technique (SIT) is currently used to eliminate tsetse fly populations in an area-wide integrated pest management (AW-IPM) context in Senegal. For SIT, tsetse mass rearing is a major milestone that associated microbes can influence. Tsetse flies can be infected with microorganisms, including the primary and obligate Wigglesworthia glossinidia, the commensal Sodalis glossinidius, and Wolbachia pipientis. In addition, tsetse populations often carry a pathogenic DNA virus, the Glossina pallidipes salivary gland hypertrophy virus (GpSGHV) that hinders tsetse fertility and fecundity. Interactions between symbionts and pathogens might affect the performance of the insect host.

Methods

In the present study, we assessed associations of GpSGHV and tsetse endosymbionts under field conditions to decipher the possible bidirectional interactions in different Glossina species. We determined the co-infection pattern of GpSGHV and Wolbachia in natural tsetse populations. We further analyzed the interaction of both Wolbachia and GpSGHV infections with Sodalis and Wigglesworthia density using qPCR.

Results

The results indicated that the co-infection of GpSGHV and Wolbachia was most prevalent in Glossina austeni and Glossina morsitans morsitans, with an explicit significant negative correlation between GpSGHV and Wigglesworthia density. GpSGHV infection levels > 103.31 seem to be absent when Wolbachia infection is present at high density (> 107.36), suggesting a potential protective role of Wolbachia against GpSGHV.

Conclusion

The result indicates that Wolbachia infection might interact (with an undefined mechanism) antagonistically with SGHV infection protecting tsetse fly against GpSGHV, and the interactions between the tsetse host and its associated microbes are dynamic and likely species specific; significant differences may exist between laboratory and field conditions.

Graphical Abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mutualistic bacteria are functionally essential to the physiological well-being of their animal hosts. They benefit their hosts by providing essential nutrients, aiding in digestion and maintaining intestinal equilibrium. Furthermore, mutualistic symbionts foster the development, differentiation, and proper function of their host’s immune system [1,2,3,4,5]. Insects provide a useful model for studying host-microbe interactions because they are associated with bacterial communities that can be easily manipulated during their host’s development [6]. Tsetse flies (Glossina spp.) accommodate various types of bacteria, including two gut-associated bacterial symbionts, the obligate Wigglesworthia glossinidia and the commensal Sodalis glossinidius, the widespread symbiont Wolbachia pipientis, and a recently discovered Spiroplasma endosymbiont [7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. In addition, tsetse flies can house different types of viral infection, including the salivary gland hypertrophy virus (GpSGHV), iflavirus, and negevirus, besides trypanosome parasites [14,15,16,17]. Symbiotic associations between insect disease vectors, gut and endosymbiotic bacteria have been particularly well studied to determine how these microbes influence their host’s ability to be infected and transmit disease [18,19,20,21,22]. For example, in tsetse flies, the obligate bacteria W. glossinidia are essential for maintaining female fecundity and the host immune system by providing important nutritional components (vitamin B6) and folate (vitamin B9) [22,23,24]. In addition, Sodalis may modulate tsetse susceptibility to infection with trypanosomes, and several studies using field-captured tsetse have noted that the prevalence of trypanosome infections positively correlates with increased Sodalis density in the fly’s gut [25,26,27,28,29]. In contrast, the exogenous bacterium Kosakonia cowanii inhibits trypanosome infection by creating an unfavorable environment for trypanosome establishment in the mid-gut [30].

Flies in the genus Glossina (tsetse flies) are unique to Africa and are of great medical and economic importance as they serve as a vector for the trypanosomes responsible for sleeping sickness in humans (human African trypanosomosis or HAT) and nagana in animals (African animal trypanosomosis or AAT) [31, 32]. The presence of tsetse and trypanosomes is considered one of the major challenges to sustainable development in Africa [33, 34]. The lack of adequate and affordable vaccines coupled with pathogen resistance to drug treatments severely limits AAT control, leaving vector control as the most feasible option for sustainable management of the disease [31, 32]. In addition to various pesticide- and trapping-based methods for tsetse control, the sterile insect technique (SIT) is considered an efficient, sustainable and environmentally friendly method when implemented in the frame of area-wide integrated pest management (AW-IPM) [35, 36]. However, the SIT requires the mass rearing of many males to be sterilized with ionizing radiation before release into the targeted area [33, 37].

Tsetse fly biology is characterized by its viviparous reproduction rendering tsetse mass rearing a real challenge. Tsetse flies nourish their intrauterine larvae from glandular secretions and give birth to fully developed larvae (obligate adenotrophic viviparity) [38, 39]. They also live considerably longer than other vector insects, which somewhat compensates for their slow reproduction rate [40]. The ability to nourish larvae on the milk gland secretion, although limiting the number of larvae produced per female lifetime (8–12), facilitates the transmition of endosymbitic bacteria and pathogens from females to larvae such as Wigglesworthia, Sodalis, Wolbachia, Spiroplasma, and GpSGHV [8, 10, 13, 41]. Moreover, as strictly hematophagous, tsetse rely on the associated endosymbionts to obtain essential nutrients for female reproduction. Therefore, tsetse well-being in mass rearing for SIT is affected by the status of its endosymbionts as well as infection with pathogenic viruses and the interactions between them. Although Wigglesworthia is an obligate endosymbiont and found in all tsetse species, Sodalis, Wolbachia, and Spiroplasma infection varied from one species to another [8, 10, 42,43,44,45]. In addition, infection with GpSGHV, although reported in different tsetse species, is mainly symptomatic in G. pallidipes [46,47,48]. As GpSGHV is horizontally transmitted via the feeding system under laboratory conditions, leading to high infection rates [49,50,51], and the virus has a negative effect on the reproductive system of the host causing reduced fecundity and fertility [52, 53], control of the virus infection is important in tsetse mass rearing for efficient production of irradiated males for SIT program implementation.

The variable responses of different tsetse species to the GpSGHV infection might indicate a possibility of the tsetse microbiota modulating the molecular dialogue among the virus, symbiont, and host, shaping the response of each species to the virus infection. It was necessary, therefore, to investigate the infection status of the major tsetse endosymbionts (Wigglesworthia, Sodalis, and Wolbachia) in different tsetse species and their potential interactions. We have recently investigated the interaction between GpSGHV and tsetse symbionts in six tsetse species after virus injection under laboratory conditions [54]. The results indicated that the interaction between the GpSGHV and tsetse symbionts is a complicated process that varies from one tsetse species to another. It is worth noting that the study of Demirbas-Uzel et al. [54] was conducted in tsetse flies maintained under controlled laboratory conditions (sustainable food availability, constant environmental conditions (temperature and humidity), and high density of the flies), which favors the increase of tsetse symbionts [45, 55, 55,56,57]. In addition, this study was done using adults artificially infected with GpSGHV by injection. Therefore, we investigated the associations of the GpSGHV and tsetse symbionts in field-collected samples by evaluating the prevalence of co-infection of GpSGHV and Wolbachia and their potential association with Wigglesworthia and Sodalis infection in natural tsetse populations. The results are also discussed in the context of developing an effective and robust mass production system of high-quality sterile tsetse flies for implementing SIT programs.

Methods

Tsetse samples, extraction of total DNA, and PCR amplifications

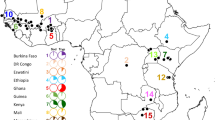

The field collection of tsetse fly samples, DNA extraction, and the PCR-based prevalence of GpSGHV and Wolbachia infections were reported previously [7, 47, 58, 59]. Based on these publications, and using G. m. morsitans, G. pallidipes, G. medicorum, G. brevipalpis, and G. austeni samples collected from Burkina Faso, South Africa, Tanzania, Zambia, and Zimbabwe, four infection patterns (i.e. presence) were determined: (i) flies PCR positive for both GpSGHV and Wolbachia (W+/V+), (ii) flies PCR positive for Wolbachia alone (W+/V−), (iii) flies PCR positive for GpSGHV alone (W−/V+), and (iv) flies PCR negative for both GpSGHV and Wolbachia (W−/V−). It has to be noted that the prevalence of the symbionts was assessed using a conventional PCR assay while their densities (see below) were determined using a qPCR assay. Since these two assays were different in several aspects including the size of the amplicons and visualization process, this resulted in some discrepancies regarding the infections status of some virus samples initially considered virus free by conventional PCR that were found to be positive during the qPCR analysis.

Analysis of the associations among SGHV and Wolbachia, Sodalis, and Wigglesworthia infection in wild tsetse populations

The associations among GpSGHV and Wolbachia, Sodalis, and Wigglesworthia were assessed by qPCR analysis. Tsetse fly samples were selected for qPCR analysis only if a given population of each species was characterized by the presence of two or three of the infection patterns (W+/V+), (W+/V−), and (W−/V+). Based on this criterion, 203 individual flies (78, 103, and 22 flies with infection pattern (W+/V+), (W+/V−), and (W−/V+), respectively) were analyzed (Table 1). The qPCR analysis was performed as previously described [47, 53, 60]. In brief, for the standard curve, total DNA was diluted tenfold before being used for qPCR analysis on a CFX96 real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) using the primers and conditions presented in Additional file 2: Table S1. The estimated copy number by qPCR for each sample compared with the standard curve was determined in diluted DNA (4 ng/μl) and corrected through the multiplication by the inverse dilution factor to reflect the GpSGHV, Wolbachia, Wigglesworthia, or Sodalis copy number (hereafter mention as density) per fly. Analysis of the Wolbachia, Wigglesworthia, Sodalis, and SGHV density levels (titers) was based only on qPCR data with the expected melting curves at 85.5–86 °C, 78.5–80 °C, 81.5–82 °C, and 76.5–77 °C, respectively. Data with a melting curve outside the indicated range were excluded from the analysis. The status of Sodalis and Wigglesworthia infection of the samples used for the qPCR analysis was not determined by traditional PCR. Based on the estimated copy number per fly for SGHV, Wolbachia, Wigglesworthia, and Sodalis, the average copy number was calculated for all tested flies. Flies with copy number values less than the median were considered infected with low density and flies with copy number value greater than the median were considered infected at a high level. The median copy numbers of the GpSGHV, Wolbachia, Sodalis, and Wigglesworthia in all tested samples were 103.31, 107.36, 106.07, and 106.84 per fly, respectively.

Statistical analysis

The proportion of single and double infections (GpSGHV and Wolbachia) in wild flies was analyzed by location and species and for all samples together using the Chi-squared test. The Chi-squared tests for independence, Spearman correlation coefficient, and Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test for repeated tests of independence were performed using Excel 2010. P-values were calculated from the data with the significance threshold selected as 0.05.

The difference in Wigglesworthia, Sodalis, Wolbachia, and GpSGHV density between different locations and tsetse species and the correlation between densities as well as preparing figures were executed in R v 4.0.5 [61] using RStudio v 1.4.1106 [62, 63] with packages ggplot2 v3.3.2.1 [64], lattice v0.20-41 [65], car (version 3.1-0) [66], ggthems (version 4.2.4) [67], and MASS v7.3-51.6 [68]. All regression analyses of symbionts and GpSGHV densities were conducted using the generalized linear model (glm) for different tsetse species and different countries with analysis of deviance table (type II tests). Pearson correlation coefficient between the density of Wolbachia and Wigglesworthia and the log transformed density of GpSGHV and Sodalis was conducted in R. The analysis details are presented in Additional file 1. Overall similarities in Wolbachia, Wigglesworthia, Sodalis, and GpSGHV density levels between tsetse species, countries, and infection pattern were shown using the matrix display and metric multidimensional scaling (mMDS) plot with bootstrap averages in PRIMER version 7 + and were displayed with a Bray and Curtis matrix based on the square root transformation [69]. The tests were based on the multivariate null hypothesis via the non-parametric statistical method PERMANOVA [70]. The PERMANOVA test was conducted on the average of the qPCR density data based on the country-species sample.

Results

Prevalence of co-infection with GpSGHV and Wolbachia in wild tsetse flies

Analysis of the Wolbachia and GpSGHV infection status for each individual tsetse adult in the previously reported data [7, 47, 58, 59] indicated that the single infection rate was 10.21% (n = 459) and 15.12% (n = 680) for GpSGHV and Wolbachia, respectively, over all taxa and locations combined (Additional file 4: Fig. S1A). No Wolbachia infection was found in two taxa, G. f. fuscipes and G. p. palpalis, and these were excluded from further examination (Table 1). A Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test for repeated tests of independence showed that infection with GpSGHV and Wolbachia did not deviate from independence across all taxa (χ2MH = 0.848, df = 1, n.s.), and individual Chi-squared tests for independence for each taxon did not show any significant deviation from independence at the Bonferroni corrected α = 0.00714 (Additional file 3: Table S2). The prevalence of co-infection of GpSGHV and Wolbachia (W+/V+) in wild tsetse populations varied based on the taxon and the location (Table 1 and Additional file 4: Fig. S1B). No co-infection was found in G. brevipalpis, G. m. submorsitans, and G. p. gambiensis, and co-infection was absent in many locations in the remaining taxa. However, a low prevalence of co-infection was found in G. medicorum (2%), G. tachinoides (0.7%), and G. pallidipes (0.2%). A relatively high prevalence of co-infection was only observed in G. austeni (26%) and G. m. morsitans (13%) (Additional file 4: Fig. S1B).

Impact of co-infection (W+/V+) on GpSGHV, Wolbachia, Sodalis, and Wigglesworthia density

GpSGHV density

The GpSGHV qPCR data showed overall no statistically significant difference between flies with different infection patterns (W+/V+), (W−/V+), and (W+/V−) (X2 = 1.4625, df = 2, P = 0.481) regardless of tsetse taxon (Additional file 5: Fig. S2A). Moreover, no significant difference in GpSGHV copy number was observed between tsetse taxa (X2 = 0.752, df = 3, P = 0.861) (Additional file 4: Fig. S1A). However, a significant difference in the virus copy number was observed between different countries (X2 = 16.234, df = 4, P = 0.0027) where the virus copy number in the flies collected from Zambia was significantly lower than those collected from South Africa, Tanzania, and Zimbabwe (Additional file 1 and 6: Fig. S3A).

Wolbachia density

The copy number of Wolbachia infection was significantly different between tsetse taxa (X2 = 6.568, df = 2, P = 0.037) (Additional file 4: Fig. S1B), between the infection statuses (X2 = 23.723, df = 2, P < 0.001) (Additional file 5: Fig. S2B), and between the countries (X2 = 73.507, df = 3, P < < 0.001) (Additional file 6: Fig. S3B). Wolbachia density was significantly higher in G. m. morsitans than in G.austeni (t = 2.029, df = 1, P = 0.0478). (Additional file 1 and 4: Fig. S1B).

Overall, a significant difference in Wolbachia density was observed in the flies with different infection patterns previously determined by conventional PCR, where flies with a (W+/V−) infection pattern showed significantly higher Wolbachia density than flies with a (W+/V+) infection pattern regardless of the tsetse species (X2 = 23.723, df = 2, P < < 0.001). This trend was observed in G. m. morsitans (t = 3.184, P = 0.0022) (Additional file 1). The Wolbachia density was highest in the flies collected from Zambia (Additional file 6: Fig. S3B). Analyzing only the flies with co-infection (W+/V+) indicated that the Wolbachia density was statistically significantly higher in G. m. morsitans than in G.austeni (t = − 2.353, df = 1, P = 0.024) (Additional file 1 and 7: Fig. S4B).

Interaction between GpSGHV infection and Wolbachia, Wigglesworthia, and Sodalis infection

The qPCR results of both Wigglesworthia and Sodalis in tsetse adults with different infection patterns (W+/V+), (W−/V+), and (W+/V−) indicated that Wigglesworthia density varies significantly between different infection patterns (X2 = 10.706, df = 2, P = 0.0047) and its density in flies with co-infection (W+/V+) was significantly lower than in those with Wolbachia infection only (W+/V−) (t = 3.137, df = 2, P = 0.0024) but did not differ significantly from flies with virus infection only (W−/V+) (t = 1.656, P = 0.102) (Additional file 5: Fig. S2C). Wigglesworthia density varies also between tsetse taxa (X2 = 33.479, df = 4, P < < 0.001) with higher density in G. m. morsitans and G.pallidipes than in G. austeni (Additional file 4: Fig. S1C) as well as between countries (X2 = 19.785, df = 3, P < 0.001) (Additional file 1 and 6: Fig. S3C).

Sodalis density also varies between tsetse taxa (X2 = 21.612, df = 3, P < 0.001) (Fig. 1D) and between countries (X2 = 21.179, df = 4, P < 0.001) (Additional file 6: Fig. S3D) but there was no significant difference between tsetse flies with different infection patterns (X2 = 0.63888, df = 2, P = 0.727) (Additional file 1 and 5: Fig. S2D).

Analyzing the pairwise correlation between the GpSGHV and each of the tsetse endosymbionts in G. austeni and G. m. morsitans (species with the highest number of flies with co-infection) indicated different types of correlation based on the insect taxa. In G. m. morsitans, the GpSGHV density has a significant negative correlation with Wolbachia density (r = − 0. 558, t = − 4.150, df = 38, P < 0.001). No flies were observed with high virus density (> 103.3 copy number) when Wolbachia density was high (~ 107.3 copy number), although this observation should be considered with caution as it is based on a small sample size. Contrary to Wolbachia, GpSGHV has a significant positive correlation with Wigglesworthia (r = 0.531, t = 3.868, df = 38, P < 0.001) but no correlation with Sodalis density (r = 0.203, t = 1.276, df = 38, P = 0.209). Wolbachia density also showed significant negative correlation with Wigglesworthia density (r = − 0.637, t = − 5.095, df = 38, P < 0.001). No flies with high Wigglesworthia density (~ 108 copy number) were detected when Wolbachia density was high (> 107.3 copy number). In contrast, Sodalis density did not show significant correlation with either Wolbachia (r = 0.193, t = 1.214, df = 38, P = 0.232) or Wigglesworthia densities (r = 0.072, t = 0.443, df = 38, P = 0.66) (Fig. 2, Additional file 1). In G. austeni, the only significant correlation was found to be positive between Sodalis and Wigglesworthia density (r = 0.602, t = 2.386, df = 10, P = 0.038) (Fig. 2, Additional file 1).

Interaction between the GpSGHV and tsetse endosymbionts Wigglesworthia, Wolbachia, and Sodalis in natural populations of G. austeni and G. m. morsitans. The density of tsetse symbionts was analyzed by qPCR, and the data of each two organisms were plotted in R. The density of GpSGHV was plotted versus the density of Wolbachia (A), Sodalis (B), and Wigglesworthia (C). The density of Wigglesworthia was plotted versus Wolbachia (D), and the density of Sodalis was plotted versus Wolbachia (E) and Wigglesworthia (F). Vertical bar A and D indicates the Wolbachia density at 109 and 108.2 copy number, respectively

The qPCR results showed that Wolbachia-infected flies had relatively high Wolbachia density (median 107.3 copies/fly) compared to the GpSGHV and other tsetse symbionts (Wigglesworthia and Sodalis) regardless of the species, country, or infection pattern (Fig. 3). The heat map analysis of the qPCR data of G. austeni and G. m. morsitans clearly indicates the contrast between Wolbachia copy number and Wigglesworthia copy number considering the infection pattern, tsetse taxa, or countries. In addition, it clearly shows the low copy number of GpSGHV in the samples showing a high Wolbachia copy number (Fig. 3, Additional file 8:Fig. S5). The bootstrap averages of the metric multidimensional scaling (mMDS) produced clusters based on the species, country, and infection pattern (Fig. 4). The PERMANOVA analysis of the density of GpSGH, Wolbachia, Wigglesworthia, and Sodalis based on the country, tsetse species, and infection pattern indicated that the clusters observed between infection pattern (P = 0.026) and country (P = 0.001) were statistically significant. The interaction between country and infection pattern was not statistically significant (P = 0.123) (Table 2).

Relative density of GpSGHV, Wigglesworthia, Sodalis, and Wolbachia in G. austeni and G. m. morsitans field-collected tsetse flies. The density of GpSGHV and tsetse symbionts was analyzed by qPCR. Data were transformed to square root and averaged based on country (A), tsetse species (B), and infection status (Sample) (C). The top and the left of the graph indicate the group averaged Bray-Curtis similarity

Metric multidimensional scaling (mMDS) of GpSGHV, Wigglesworthia, Sodalis, and Wolbachia relative density in field-collected tsetse flies. The mMDS of GpSGHV, Wigglesworthia, Sodalis, and Wolbachia relative density was performed in respect to infection status (Sample) (A), tsetse species (B), or country (C). av average

Discussion

The prevalence of GpSGHV and Wolbachia in natural tsetse populations clearly indicated that the two infections were independent (not correlated) in most of the tested tsetse species with only G. m. morsitans and G. austeni presenting a high proportion of co-infections. However, the number of co-infections originally determined by conventional PCR may have been underestimated with conventional PCR as the qPCR analysis carried out in the frame of the present study clearly indicated that a number of initially considered virus-free samples were found to be positive, albeit at low density. It should also be noted that the Wolbachia strains infecting G. m. morsitans and G. austeni are closely related but different, as has been shown by both MLST analysis and, more recently, genome sequencing [7, 40, 71].

Analysis of G. morsitans and G. austeni co-infected samples suggested that low density of GpSGHV is associated with high density of Wolbachia. Due to the low number of individuals showing this correlation, further analysis is required. Moreover, the screen of wild tsetse populations for GpSGHV and Wolbachia infection indicated that not all Glossina species harbor Wolbachia or GpSGHV. Furthermore, Wolbachia and GpSGHV prevalence was found to differ not only between different tsetse host species but also between different populations within the same tsetse species [7, 11, 47, 58, 59, 72].

The potential negative impact (antagonistic effect) of Wolbachia density on the GpSGHV density in natural tsetse populations is in agreement with the recent report on the interaction of Wolbachia and GpSGHV infection in colonized tsetse populations [54]. However, the number of tested flies was not equally distributed between the tsetse taxa and locations, which might explain the lack of detected co-infections in some taxa and, therefore, the low number of taxa (G. austeni and G. m. morsitans) used for investigating the interactions between the GpSGHV and tsetse symbionts. The negative correlation between Wolbachia and GpSGHV infections was also reported in wild-caught G. f. fuscipes collected from Uganda [72]. This conflicts with our findings as no G. f. fuscipes flies with GpSGHV were reported, which might be due to the low number of tested flies used in our study (n = 53).

Several reports have discussed and well documented the negative effect of Wolbachia on RNA viruses in different insect models such as mosquitoes and Drosophila [73,74,75], although there have also been reports about Wolbachia enhancement of both RNA and DNA viruses [76,77,78]. It is worth mentioning that the negative correlation of Wolbachia with GpSGHV was observed only when Wolbachia density was high as the results show the absence of high density (> 103.7) GpSGHV infection with high-density Wolbachia infection (> 107.5). However, at low Wolbachia density co-infection occurs with a prevalence of > 10%. Although our study indicated a correlation between high-density Wolbachia and low-density GpSGHV, previous reports suggested that the negative impact of Wolbachia on insect viruses is density dependent [76, 79].

The assessment of the infection density (copy number per fly) of all four microbes (GpSGHV, Wolbachia, Wigglesworthia, and Sodalis) in the same tsetse flies indicated that Wolbachia infection at high density has a significant negative correlation with Wigglesworthia infection in G. m. morsitans but not in G. austeni. However, the latter might be due to the low number of analyzed G. austeni flies (n = 21) compared to G. m. morsitans (n = 91). On the other hand, Wolbachia density levels do not correlate with Sodalis. The nature of the negative interaction between Wolbachia and Wigglesworthia is unclear. Whether this negative correlation between Wolbachia and Wigglesworthia is present in other tsetse species beyond G. m. morsitans remains to be seen.

The positive correlation between GpSGHV infection and Wigglesworthia infection observed in G. m. morsitans conflicts with the negative correlation observed in the same species of colonized flies [54]. This result might reflect a specific adaptation between a specific strain of Wigglesworthia, which reacts in a specific way to increase its density in the presence of GpSGHV as a manner to restore and enhance the host immune system against the virus infection [80]. The difference in the interaction between the GpSGHV and Wigglesworthia between the results of this study and the results of Demirbas-Uzel et al. [54] might be due to: (i) difference in the host strain/genotype as the G. m. morsitans individuals were collected from several countries in east Africa (Tanzania, Zambia, and Zimbabwe) while the colonized flies originated from Zimbabwe and have been maintained in the colony since 1997; (ii) different strain(s) of Wigglesworthia circulating in the field samples compared to the ones present in colonized flies [60]; (iii) different strain(s) of the GpSGHV in the field samples [58]; (iv) difference between field and laboratory conditions where the stress from handling the large number of flies in high density in the laboratory might negatively affect Wigglesworthia density levels and/or performance. The same reasons may also explain the difference observed between field and laboratory samples regarding the interactions between GpSGHV and Sodalis.

Conclusions

The present study, despite its limitations regarding the size of samples and the lack of knowledge about the age, nutritional and trypanosome infection status, and environmental conditions at the time of collection of field specimens, shows a snapshot image of the density levels of tsetse symbionts and SGHV under field conditions and clearly indicates that the interactions/association between the tsetse host and its associated microbes are dynamic and likely species specific, and significant differences may exist between laboratory and field conditions. Further studies are needed to clarify the interaction between tsetse symbionts and GpSGHV under field conditions.

Availability of data and materials

Materials described in the paper, including all relevant raw data, are available in this link. https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/X15PQF

References

Chu H, Mazmanian SK. Innate immune recognition of the microbiota promotes host-microbial symbiosis. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:668–75.

Khosravi A, Yáñez A, Price JG, Chow A, Merad M, Goodridge HS, et al. Gut microbiota promote hematopoiesis to control bacterial infection. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;15:374–81.

Douglas AE. Multiorganismal insects: diversity and function of resident microorganisms. Annu Rev Entomol. 2015;60:17–34.

de Agüero MG, Ganal-Vonarburg SC, Fuhrer T, Rupp S, Uchimura Y, Li H, et al. The maternal microbiota drives early postnatal innate immune development. Science. 2016;351:1296–302.

Marchesi JR, Adams DH, Fava F, Hermes GDA, Hirschfield GM, Hold G, et al. The gut microbiota and host health: a new clinical frontier. Gut. 2016;65:330–9.

Benoit JB, Vigneron A, Broderick NA, Wu Y, Sun JS, Carlson JR, et al. Symbiont-induced odorant binding proteins mediate insect host hematopoiesis. eLife. 2017;6:e19535.

Doudoumis V, Tsiamis G, Wamwiri F, Brelsfoard C, Alam U, Aksoy E, et al. Detection and characterization of Wolbachia infections in laboratory and natural populations of different species of tsetse flies (genus Glossina). BMC Micobiol. 2012;12:S3.

Doudoumis V, Blow F, Saridaki A, Augustinos AA, Dyer NA, Goodhead IB, et al. Challenging the Wigglesworthia, Sodalis, Wolbachia symbiosis dogma in tsetse flies: Spiroplasma is present in both laboratory and natural populations. Sci Rep. 2017;7:4699.

Maltz MA, Weiss BL, O’Neill M, Wu Y, Aksoy S. OmpA-mediated biofilm formation is essential for commensal bacterium Sodalis glossinidius to colonize the tsetse fly gut. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:7760–8.

Wang J, Brelsfoard C, Wu Y, Aksoy S. Intercommunity effects on microbiome and GpSGHV density regulation in tsetse flies. J Invertebr Pathol. 2013;112:S32-9.

Wang J, Weiss BL, Aksoy S. Tsetse fly microbiota: form and function. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2013;3:69.

Schneider DI, Saarman N, Onyango MG, Hyseni C, Opiro R, Echodu R, et al. Spatio-temporal distribution of Spiroplasma infections in the tsetse fly (Glossina fuscipes fuscipes) in northern Uganda. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13:e0007340.

Son JH, Weiss BL, Schneider DI, Dera K-SM, Gstöttenmayer F, Opiro R, et al. Infection with endosymbiotic Spiroplasma disrupts tsetse (Glossina fuscipes fuscipes) metabolic and reproductive homeostasis. PLoS Pathog. 2021;17:e1009539.

Abd-Alla AMM, Cousserans F, Parker AG, Jehle JA, Parker NJ, Vlak JM, et al. Genome analysis of a Glossina pallidipes salivary gland hypertrophy virus (GpSGHV) reveals a novel large double-stranded circular DNA virus. J Virol. 2008;82:4595–611.

Abd-Alla AM, Kariithi HM, Cousserans F, Parker NJ, Ince IA, Scully ED, et al. Comprehensive annotation of the Glossina pallidipes salivary gland hypertrophy virus from Ethiopian tsetse flies: a proteogenomics approach. J Gen Virol. 2016;97:1010–31.

Demirbas-Uzel G, Kariithi HM, Parker AG, Vreysen MJB, Mach RL, Abd-Alla AMM. Susceptibility of tsetse species to Glossina pallidipes salivary gland hypertrophy virus (GpSGHV). Front Microbiol. 2018;9:701.

Meki I, Huditz H-I, Strunov A, Van Der Vlugt R, Kariithi HM, Rezaezapanah M, et al. Characterization and tissue tropism of newly identified iflavirus and negevirus in tsetse flies Glossina morsitans morsitans. Viruses 2021;13(12):2472.

Weiss B, Aksoy S. Microbiome influences on insect host vector competence. Trends Parasitol. 2011;27:514–22.

Narasimhan S, Fikrig E. Tick microbiome: the force within. Trends Parasitol. 2015;31:315–23.

Dey R, Joshi AB, Oliveira F, Pereira L, Guimarães-Costa AB, Serafim TD, et al. Gut microbes egested during bites of infected sand flies augment severity of leishmaniasis via inflammasome-derived IL-1β. Cell Host Microbe. 2018;23:134-143.e6.

Song X, Wang M, Dong L, Zhu H, Wang J. PGRP-LD mediates A. stephensi vector competency by regulating homeostasis of microbiota-induced peritrophic matrix synthesis. PLoS Pathog. 2018;14:e1006899.

Rio RVM, Jozwick AKS, Savage AF, Sabet A, Vigneron A, Wu Y, et al. Mutualist-provisioned resources impact vector competency. mBio. 2019;10:e00018-19.

Michalkova V, Benoit JB, Weiss BL, Attardo GM, Aksoy S. Vitamin B6 generated by obligate symbionts is critical for maintaining proline homeostasis and fecundity in tsetse flies. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80:5844–53.

Michalkova V, Benoit JB, Attardo GM, Medlock J, Aksoy S. Amelioration of reproduction-associated oxidative stress in a viviparous insect is critical to prevent reproductive senescence. PLoS One. 2014;9:e87554.

Moloo SK, Kabata JM, Waweru F, Gooding RH. Selection of susceptible and refractory lines of Glossina morsitans centralis for Trypanosoma congolense infection and their susceptibility to different pathogenic Trypanosoma species. Med Vet Entomol. 1998;12:391–8.

Farikou O, Thevenon S, Njiokou F, Allal F, Cuny G, Geiger A. Genetic diversity and population structure of the secondary symbiont of tsetse flies, Sodalis glossinidius, in sleeping sickness foci in Camerooon. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5:e1281.

Soumana IH, Simo G, Njiokou F, Tchicaya B, Abd-Alla AMM, Cuny G, et al. The bacterial flora of tsetse fly midgut and its effect on trypanosome transmission. J Invertebr Pathol. 2013;112:S89-93.

Aksoy E, Telleria E, Echodu R, Wu Y, Okedi LM, Weiss BL, et al. Analysis of multiple tsetse fly populations in Uganda reveals limited diversity and species-specific gut microbiota. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80:4301–12.

Griffith BC, Weiss BL, Aksoy E, Mireji PO, Auma JE, Wamwiri FN, et al. Analysis of the gut-specific microbiome from field-captured tsetse flies, and its potential relevance to host trypanosome vector competence. BMC Microbiol. 2018;18:146.

Weiss BL, Maltz MA, Vigneron A, Wu Y, Walter KS, O’Neill MB, et al. Colonization of the tsetse fly midgut with commensal Kosakonia cowanii Zambiae inhibits trypanosome infection establishment. PLoS Pathog. 2019;15:e1007470.

Leak SGA. Tsetse biology and ecology: their role in the epidemiology and control of trypanosomosis. Wallingford: CABI Publishing; 1998.

Simarro PP, Louis FJ, Jannin J. Sleeping sickness, forgotten illness: what are the impact in the field? MedTrop. 2003;63:231–5.

Dyck VA, Hendrichs J, Robinson AS. Sterile insect: technique principles and practice in area-wide integrated pest management. 2nd ed. Boco Raton: CRC Press; 2021.

Feldmann U, Dyck VA, Mattioli R, Jannin J, Vreysen MJB. Impact of tsetse fly eradication programmes using the sterile insect technique. In: Dyck VA, Hendrichs JP, Robinson AS, editors. Sterile insect technique: principles and practice area-wide integrated pest management. 2nd ed. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2021. p. 701–30.

Vreysen MJB, Saleh KM, Ali MY, Abdulla AM, Zhu Z-R, Juma KG, et al. Glossina austeni (Diptera: Glossinidae) eradicated on the island of Unguja, Zanzibar, using the sterile insect technique. J Econ Entomol. 2000;93:123–35.

Hendrichs MA, Wornoayporn V, Katsoyannos BI, Hendrichs JP. Quality control method to measure predator evasion in wild and mass-reared Mediterranean fruit flies (Diptera: Tephritidae). Fla Entomol. 2007;90:64–70.

Vreysen MJB, Abd-Alla AMM, Bourtzis K, Bouyer J, Caceres C, de Beer C, et al. The insect pest control laboratory of the joint FAO/IAEA programme: ten years (2010–2020) of research and development, achievements and challenges in support of the sterile insect technique. Insects. 2021;12:346.

Attardo GM, Lohs C, Heddi A, Alam UH, Yildirim S, Aksoy S. Analysis of milk gland structure and function in Glossina morsitans: milk protein production, symbiont populations and fecundity. J Insect Physiol. 2008;54:1236–42.

Belda E, Moya A, Bentley S, Silva FJ. Mobile genetic element proliferation and gene inactivation impact over the genome structure and metabolic capabilities of Sodalis glossinidius, the secondary endosymbiont of tsetse flies. BMC Genom. 2010;11:449.

International Glossina Genome Initiative. Genome sequence of the tsetse fly (Glossina morsitans): vector of African trypanosomiasis. Science. 2014;344:380–6.

Abd-Alla AMM, Kariithi HM, Parker AG, Robinson AS, Kiflom M, Bergoin M, et al. Dynamics of the salivary gland hypertrophy virus in laboratory colonies of Glossina pallidipes (Diptera: Glossinidae). Virus Res. 2010;150:103–10.

Aksoy S. Tsetse—A haven for microorganisms. Parasitol Today. 2000;16:114–8.

Aksoy S, Weiss B, Attardo GM. Paratransgenesis applied for control of tsetse transmitted sleeping sickness. Transgenesis and the management of vector-borne disease (2008): 35-48.

Alam U, Medlok J, Brelsfoard C, Pais R, Lohs C, Balmand S, et al. Wolbachia symbiont infections induce strong cytoplasmic incompatibility in the tsetse fly Glossina morsitans. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002415.

Doudoumis V, Alam U, Aksoy E, Abd-Alla AMM, Tsiamis G, Brelsfoard C, et al. Tsetse-Wolbachia symbiosis: comes of age and has great potential for pest and disease control. J Invertebr Pathol. 2013;112:S94-103.

Lietze VU, Abd-Alla AMM, Vreysen MJB, Geden CJ, Boucias DG. Salivary gland hypertrophy viruses: a novel group of insect pathogenic viruses. Annu Rev Entomol. 2010;56:63–80.

Kariithi HM, Ahmadi M, Parker AG, Franz G, Ros VID, Haq I, et al. Prevalence and genetic variation of salivary gland hypertrophy virus in wild populations of the tsetse fly Glossina pallidipes from southern and eastern Africa. J Invertebr Pathol. 2013;112:S123-32.

Abd-Alla AMM, Kariithi HM, Bergoin M. Managing pathogens in insect mass-rearing for the sterile insect technique, with the tsetse fly salivary gland hypertrophy virus as an example. In: Dyck VA, Hendrichs JP, Robinson AS, editors. Sterile insect technique: principles and practice area-wide integrated pest management. 2nd ed. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2021. p. 317–54.

Jura WGZO, Otieno LH, Chimtawi MMB. Ultrastructural evidence for trans-ovum transmission of the DNA virus of tsetse, Glossina pallidipes (Diptera: Glossinidae). Curr Microbiol. 1989;18:1–4.

Sang RC, Jura WGZO, Otieno LH, Ogaja P. Ultrastructural changes in the milk gland of tsetse Glossina morsitans centralis (Diptera; Glissinidae) female infected by a DNA virus. J Invertebr Pathol. 1996;68:253–9.

Sang RC, Jura WGZO, Otieno LH, Mwangi RW. The effects of a DNA virus infection on the reproductive potential of female tsetse flies, Glossina morsitans centralis and Glossina morsitans morsitans (Diptera: Glossinidae). Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1998;93:861–4.

Jaenson TGT. Virus-like rods associated with salivary gland hyperplasia in tsetse, Glossina pallidipes. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1978;72:234–8.

Abd-Alla AMM, Cousserans F, Parker A, Bergoin M, Chiraz J, Robinson A. Quantitative PCR analysis of the salivary gland hypertrophy virus (GpSGHV) in a laboratory colony of Glossina pallidipes. Virus Res. 2009;139:48–53.

Demirbas-Uzel G, Augustinos AA, Doudoumis V, Parker AG, Tsiamis G, Bourtzis K, et al. Interactions between tsetse endosymbionts and Glossina pallidipes salivary gland hypertrophy virus in Glossina hosts. Front Microbiol. 2021;12:1295.

Baker RD, Maudlin I, Milligan PJM, Molyneux DH, Welburn SC. The possible role of Rickettsia-like organisms in trypanosomiasis epidemiology. Parasitology. 1990;100:209–17.

Soumana IH, Berthier D, Tchicaya B, Thevenon S, Njiokou F, Cuny G, et al. Population dynamics of Glossina palpalis gambiensis symbionts, Sodalis glossinidius, and Wigglesworthia glossinidia, throughout host-fly development. Infect Genet Evol. 2013;13:41–8.

Dennis JW, Durkin SM, Downie JEH, Hamill LC, Anderson NE, MacLeod ET. Sodalis glossinidius prevalence and trypanosome presence in tsetse from Luambe National Park, Zambia. Parasites & vectors. 2014;7:378.

Meki IK, Kariithi HM, Ahmadi M, Parker AG, Vreysen MJB, Vlak JM, et al. Hytrosavirus genetic diversity and eco-regional spread in Glossina species. BMC Microbiol. 2018;18:143.

Ouedraogo GMS, Demirbas-Uzel G, Rayaisse J-B, Gimonneau G, Traore AC, Avgoustinos A, et al. Prevalence of trypanosomes, salivary gland hypertrophy virus and Wolbachia in wild populations of tsetse flies from West Africa. BMC Microbiol. 2018;18:153.

Demirbas-Uzel G, De Vooght L, Parker AG, Vreysen MJB, Mach RL, Van Den Abbeele J, et al. Combining paratransgenesis with SIT: impact of ionizing radiation on the DNA copy number of Sodalis glossinidius in tsetse flies. BMC Microbiol. 2018;18:160.

R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2021. November 2021.

Baier T, Neuwirth E. Excel :: COM :: R. Comput Stat. 2007;22:91–108. November 2021.

RStudio Team. RStudio: integrated development environment for R. Boston: RStudio, PBC; 2022. November 2021.

Wickham H. ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. New York: Springer; 2016. November 2021.

Sarkar D. Lattice: multivariate data visualization with R. Springer Science and Business Media; 2008.

Fox J, Weisberg S. An R companion to applied regression, Second Edition. Third. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2019. November 2021.

Arnold JB. ggthemes: extra themes, scales and geoms for “ggplot2”. R package version 4.2.4. 2021. November 2021.

Venables WN, Ripley BD. Modern Applied Statistics with S. Fourth. New York: Springer; 2002. November 2021.

Clarke KR, Gorley RN. Getting started with PRIMER v7. 2016. November 2021.

Anderson MJ. A new method for non-parametric multivariate analysis of variance. Austral Ecol. 2001;26:32–46.

Attardo GM, Abd-Alla AMM, Acosta-Serrano A, Allen JE, Bateta R, Benoit JB, et al. Comparative genomic analysis of six Glossina genomes, vectors of African trypanosomes. Genome Biol. 2019;20:187.

Alam U, Hyseni C, Symula RE, Brelsfoard C, Wu Y, Kruglov O, et al. Implications of microfauna-host interactions for trypanosome transmission dynamics in Glossina fuscipes fuscipes in Uganda. Appl Env Microbiol. 2012;78:4627–37.

Hedges LM, Brownlie JC, O’Neill SL, Johnson KN. Wolbachia and virus protection in insects. Science. 2008;322:702.

Teixeira L, Ferreira A, Ashburner M. The bacterial symbiont Wolbachia induces resistance to RNA viral infections in Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e1000002.

Johnson KN. The impact of Wolbachia on Virus infection in mosquitoes. Viruses. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute; 2015; 7:5705–17. Accessed 2 Aug 2020.

Parry R, Bishop C, De Hayr L, Asgari S. Density-dependent enhanced replication of a densovirus in Wolbachia-infected Aedes cells is associated with production of piRNAs and higher virus-derived siRNAs. Virology. 2019; 528:89–100. Accessed 2 Aug 2020.

Parry R, Asgari S. Aedes Anphevirus: an insect-specific virus distributed worldwide in Aedes aegypti mosquitoes that has complex interplays with wolbachia and dengue virus infection in cells. J Virol. 2018;92:e00224-18.

Altinli M, Lequime S, Atyame C, Justy F, Weill M, Sicard M. Wolbachia modulates prevalence and viral load of Culex pipiens densoviruses in natural populations. Mol Ecol. 2020;29:4000–13.

Lu P, Bian G, Pan X, Xi Z. Wolbachia induces density-dependent inhibition to dengue virus in mosquito cells. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6:e1754.

Weiss BL, Wang J, Aksoy S. Tsetse immune system maturation requires the presence of obligate symbionts in larvae. PLoS Biol. 2011;9:e1000619.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Ms. Carmen Marin, Mr. Adun Henry, and Mr. Abdul Hasim. Mohammed for their technical support.

Funding

This study was supported by the Joint FAO/IAEA Insect Pest Control Subprogramme.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MMD and DUG: performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. AAA and VD: performed the experiments, and critically revised the manuscript. AGP: analyzed data and critically revised the manuscript. GT: critically revised the manuscript. KB: conceived the study, designed the experiments, interpreted the data, contributed to the drafting, and critically revised the manuscript. AMMA conceived the study, designed the experiments, interpreted the data, and drafted the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1

: Interactions between tsetse endosymbionts and Glossina pallidipes salivary gland hypertrophy virus in wild tsetse populations.

Additional file 2

: Table S1. List of primers used for quantitative PCR (qPCR) analyses in Glossina species.

Additional file 3

: Table S2. Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test for repeated tests of independence with continuity correction on the coingection of GpSGHV and Wolbachia in wild tsetse species.

Additional file 4

: Figure S1. Prevalence of GpSGHV and Wolbachia co-infection in natural tsetse populations. A: In all tsetse species; B: in each tsetse species. GpSGHV and Wolbachia prevalence was determined by PCR as described previously [7,47].

Additional file 5

: Figure S2. Density levels of GpSGHV (A), Wolbachia (B), Wigglesworthia (C), and Sodalis (D) determined by qPCR in tsetse flies with different GpSGHV and Wolbachia infection statuses. The copy number was determined by qPCR. Values indicated by a different small letter differ significantly at the 5% level. W+/V+: flies infected with both Wolbachia and GpSGHV; W+/V-: flies infected only with Wolbachia; W-/V-+: flies infected only with GpSGHV. GpSGHV and Wolbachia infection status was determined by conventional PCR as described previously [7,47].

Additional file 6

: Figure S3. Density levels of GpSGHV (A), Wolbachia (B), Wigglesworthia (C), and Sodalis (D) in tsetse flies collected from different countries. The copy number was determined by qPCR. Values indicated by a different small letter differ significantly at the 5% level.

Additional file 7

: Figure S4. Impact of GpSGHV and Wolbachia co-infection (W+/V+) on the density levels of GpSGHV (A), Wolbachia (B), Wigglesworthia (C), and Sodalis (D) in different tsetse species. The copy number was determined by qPCR. Values indicated by the same lower case letter do not differ significantly at the 5% level.

Additional file 8

: Figure S5. Relative density of GpSGHV, Wigglesworthia, Sodalis, and Wolbachia in G. austeni and G. m. morsitans field-collected tsetse flies. The density of GpSGHV and tsetse symbionts was analyzed by qPCR. Data were transformed to square root and averaged based on countries and species (A), countries and infection status (sample) (B), and countries, species, and infection status (sample) (C). The top and the left of the graph indicate the group averaged Bray-Curtis similarity.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Dieng, M.M., Augustinos, A.A., Demirbas-Uzel, G. et al. Interactions between Glossina pallidipes salivary gland hypertrophy virus and tsetse endosymbionts in wild tsetse populations. Parasites Vectors 15, 447 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-022-05536-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-022-05536-9