Abstract

Background

Wolbachia is a genus of endosymbiotic α-Proteobacteria infecting a wide range of arthropods and filarial nematodes. Wolbachia is able to induce reproductive abnormalities such as cytoplasmic incompatibility (CI), thelytokous parthenogenesis, feminization and male killing, thus affecting biology, ecology and evolution of its hosts. The bacterial group has prompted research regarding its potential for the control of agricultural and medical disease vectors, including Glossina spp., which transmits African trypanosomes, the causative agents of sleeping sickness in humans and nagana in animals.

Results

In the present study, we employed a Wolbachia specific 16S rRNA PCR assay to investigate the presence of Wolbachia in six different laboratory stocks as well as in natural populations of nine different Glossina species originating from 10 African countries. Wolbachia was prevalent in Glossina morsitans morsitans, G. morsitans centralis and G. austeni populations. It was also detected in G. brevipalpis, and, for the first time, in G. pallidipes and G. palpalis gambiensis. On the other hand, Wolbachia was not found in G. p. palpalis, G. fuscipes fuscipes and G. tachinoides. Wolbachia infections of different laboratory and natural populations of Glossina species were characterized using 16S rRNA, the wsp (Wolbachia Surface Protein) gene and MLST (Multi Locus Sequence Typing) gene markers. This analysis led to the detection of horizontal gene transfer events, in which Wobachia genes were inserted into the tsetse flies fly nuclear genome.

Conclusions

Wolbachia infections were detected in both laboratory and natural populations of several different Glossina species. The characterization of these Wolbachia strains promises to lead to a deeper insight in tsetse flies-Wolbachia interactions, which is essential for the development and use of Wolbachia-based biological control methods.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Wolbachia are a highly diverse group of intracellular, maternally inherited endosymbionts belonging to the α-Proteobacteria [1]. The bacteria infect a wide range of arthropods, including at least 65% of insect species [2–4], as well as filarial nematodes [5]. Wolbachia induce a range of reproductive abnormalities in their arthropod hosts, such as cytoplasmic incompatibility (CI), parthenogenesis, male-killing and feminization [1, 6–11], while they have developed mutualistic associations with filarial nematodes [12–14]. The ability of Wolbachia to cause these reproductive phenotypes allows them to spread efficiently and rapidly into host populations [4, 9]. Wolbachia has attracted much interest for its role in biological, ecological and evolutionary processes, as well as for its potential for the development of novel and environment friendly strategies for the control of insect pests and disease vectors [15–22].

Tsetse flies, the sole vectors of pathogenic trypanosomes in tropical Africa, infect many vertebrates, causing sleeping sickness in humans and nagana in animals [23]. It is estimated by the World Health Organization (WHO) that 60 million people in Africa are at risk of contracting sleeping sickness (about 40% of the continent's population). The loss of local livestock from nagana amounts to 4.5 billion U.S. dollars annually [24, 25]. Thanks to a vigorous campaign led by the WHO and various NGOs, the infected population has declined to an estimated 10,000, following epidemics that killed thousands of Africans [26]. Given that the disease affects remote areas, it is, however, likely that many cases may remain unreported. Should active case finding and treatment be discontinued, it would be prudent to maintain vector surveillance and control measures to prevent (re)emergence of the disease as was witnessed in the early 1990’s in various parts of the continent [26, 27].

Wolbachia-induced cytoplasmic incompatibility has been suggested as a potential tool to suppress agricultural pests and disease vectors [8, 21, 22, 28–30]. Another potential control approach is based on a replacement strategy, where parasite-susceptible fly populations would be replaced with genetically modified strains that are unable to transmit the pathogenic parasites. Towards this end, a paratransgenic modification approach has been developed for tsetse flies. It has been possible to culture and genetically transform a tsetse flies symbiont, the commensal bacterium Sodalis glossinidius. The expression of biological anti-parasitic in Sodalis and reconstitution of tsetse flies with the recombinant symbionts can yield modified parasite resistant flies [31, 32]. Methods that would drive the modified insects into natural population are, however, necessary to implement this approach. To this end, greater insight in tsetse flies-symbiont interactions, with focus on their implications for biological control methods, is essential [33].

The genus Wolbachia is highly diverse and is currently divided into 10 supergroups (A to K, although the validity of supergroup G is disputed) [34–40], while strain genotyping is most often based on a multi locus sequence typing system (MLST) which includes the sequences of five conserved genes (gatB, coxA, hcpA, ftsZ and fbpA), as well as on the amino acid sequences of the four hypervariable regions (HVRs) of the WSP protein [41]. Species of the genus Glossina (Diptera: Glossinidae) including G. morsitans morsitans, G. austeni and G. brevipalpis are known to harbour Wolbachia infections [42, 43], which belong to supergroup A based on the Wolbachia surface protein (wsp) gene [42, 44].

Several recent studies reported that Wolbachia genes, in some cases even large chromosomal segments, have been horizontally transferred to host chromosomes. Such events have been described in a variety of insect and nematode hosts, including the adzuki bean beetle Callosobruchus chinensis, the fruit fly Drosophila ananassae, a parasitoid wasp of the genus Nasonia, the mosquito Aedes aegypti, the pea aphid Acyrthosiphon pisum, the longicorn beetle Monochamus alternatus and filarial nematodes of the genera Onchocerca, Brugia and Dirofilaria [45–52]. Interestingly, some of these genes are highly transcribed suggesting that laterally transferred bacterial genes can be of functional importance [48–50].

In the present study, we report on the presence of Wolbachia infections in laboratory and natural populations of Glossina species. The characterization of these Wolbachia strains is based on the use of 16S rRNA, wsp and MLST gene markers. In addition, we report horizontal gene transfer events of Wolbachia genes to G. m. morsitans chromosomes.

Methods

Sample collection and DNA isolation

Glossina specimens were collected in ten countries in Africa (Tanzania, South Africa, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Kenya, Senegal, Guinea, Ethiopia, Uganda, and Democratic Republic of Congo - Zaire). Upon their arrival in the lab, all tsetse flies specimens have been immediately used for DNA extraction. DNA samples were stored at -20oC until their use. Laboratory strains from FAO/IAEA (Seibersdorf), Yale University (EPH), Slovak Academy of Sciences (SAS-Bratislava), Kenya (KARI-TRC), Burkina Faso (CIRDES) and Antwerp were also included in the analysis. DNA from adult flies was isolated according to Abd-Alla et al. 2007 [53], using the Qiagen DNeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), following the manufacturers’ instructions, except for the samples from Antwerp and Bratislava, to which the CTAB (Cetyl trimethylammonium bromide) DNA isolation method was applied [54]. G. m. morsitans fertile females were maintained on blood meals supplemented with 10% (w/v) yeast extract (Becton Dickinson) and 20 ug/ml of tetracycline. Flies were fed every 48h for the duration of their life span. The resulting progeny are aposymbiotic (GmmApo) in that they lack their natural endosymbionts, Wigglesworthia and Wolbachia (Alam and Aksoy, personal communication). Aposymbiotic progeny were used for detection of nuclear Wolbachia DNA.

PCR screen and MLST

A total of 3750 specimens of nine Glossina species (G. m. morsitans, G. m. centralis, G. austeni, G. brevipalpis, G. pallidipes, G. p. palpalis, G. p. gambiensis, G. fuscipes fuscipes and G. tachinoides) were screened for the presence of Wolbachia strains. The detection is based on the Wolbachia 16S rRNA gene and results in the amplification of an about 438 base pairs long DNA fragment with the Wolbachia specific primers wspecF and wspecR (see Additional file 1- Supplementary Table 1). The mitochondrial gene 12S rRNA was used as positive control for amplification; the primers 12SCFR (5'primer) 5'-GAG AGT GAC GGG CGA TAT GT-3’ and 12SCRR (3' primer) 5'-AAA CCA GGA TTA GAT ACC CTA TTA T-3' were used, which amplify a 377 bp fragment of the gene [55]. PCR amplifications were performed in 20 μl reaction mixtures containing 4 μl 5x reaction buffer (Promega), 1.6 μl MgCl2 (25mM), 0.1 μl deoxynucleotide triphosphate mixture (25 mM each), 0.5 μl of each primer (25 μM), 0.1 μl of Taq (Promega 1U/μl), 12.2 μl water and 1 μl of template DNA. The PCR protocol was: 35 cycles of 30 sec at 95°C, 30 sec at 54°C and 1 min at 72 °C.

The Wolbachia strains present in eleven selected Wolbachia-infected Glossina specimens from different areas and species were genotyped with MLST- and wsp-based approaches. The wsp and MLST genes (gatB, coxA, hcpA, fbpA and ftsZ) were amplified using the respective primers reported in [41] (see Additional file 1- Supplementary Table 1). Gene fragments were amplified using the following PCR mixes: 4 μl of 5x reaction buffer (Promega), 1.6 μl MgCl2 (25mM), 0.1 μl deoxynucleotide triphosphate mixture (25 mM each), 0.5 μl of each primer (25 μM), 0.1 μl of Taq (Promega 1U/μl), 12.2 μl water and 1 μl of template. PCR reactions were performed using the following program: 5 min of denaturation at 95 °C, followed by 35 cycles of 30 sec at 95°C, 30 sec at the appropriate temperature for each primer pair (52°C for ftsZ, 54°C for gatB, 55°C for coxA, 56°C for hcpA, 58°C for fbpA and wsp) and 1 min at 72 °C. All reactions were followed by a final extension step of 10 min at 72°C.

Given the presence of products of unpredicted size, all PCR products of genes 16S rRNA, wsp and MLST from the eleven selected populations were ligated into a vector (pGEM-T Easy Vector System) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and then transformed into competent DH5α cells, which were plated on ampicillin/X-gal selection plates (the exception being G. m. centralis, for which direct sequencing of PCR products was employed) Three to six clones were directly subjected to PCR using the primers T7 and SP6. For each sample, a majority-rule consensus sequence was created. The colony PCR products were purified using a PEG (Polyethylene glycol) - NaCl method [56]. Both strands of the products were sequenced using the universal primers T7 and SP6. A dye terminator-labelled cycle sequencing reaction was conducted with the BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (PE Applied Biosystems). Reaction products were analysed using an ABI PRISM 310 Genetic Analyzer (PE Applied Biosystems).

Tissue specific detection of cytoplasmic and nuclear WolbachiaDNA

To detect the presence of cytoplasmic or nuclear Wolbachia genes in different tissues, DNA extracts were prepared from gut, ovary, testes, and carcasses (remaining fly tissues after organ extraction) of Wolbachia infected and tetracycline-treated (Wolbachia-free) teneral two-day old G. m. morsitans female and male adult flies from the Yale University laboratory colony. Dissections were performed in 1X PBST ((3.2 mM Na2HPO4, 0.5 mM KH2PO4, 1.3 mM KCl, 135 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20, pH 7.4), and dissected tissues were placed in 200 μl of lysis buffer (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). The DNA was isolated using a Qiagen DNeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. PCR amplication of 16S rRNA, fbpA, and wsp were performed using the primers wspecF/wspecR, fbpA_F1 / fbpA_R1 and 81F / 691R, respectively [2, 41, 57] (see Additional file 1- Supplementary Table 1). PCR mixes of 25 μl contained 5 μl of 5x reaction buffer (Promega, Madison, WI), 3 μl MgCl2 (25mM), 0.5 μl deoxynucleotide triphosphate mixture (25 mM each), 0.5 μl of each primer (10 μM), 0.125 μl of Taq (Promega, Valencia, CA) (1U/μl), 14.375 μl water and 1 μl of template DNA. The PCR protocol was: 35 cycles of 30 sec at 95°C, 30 sec at 54°C and 1 min at 72 °C.

Phylogenetic analysis

All Wolbachia gene sequences generated in this study were manually edited with SeqManII by DNAStar and aligned using MUSCLE [58] and ClustalW [59], as implemented in Geneious 5.3.4 [60], and adjusted by eye. Phylogenetic analyses were performed using Bayesian Inference (BI) and Maximum-Likelihood (ML) estimation for a concatenated data set of the protein-coding genes (gatB, fbpA, hcpA, ftsZ and coxA) and for wsp separately. For the Bayesian inference of phylogeny, PAUP version 4.0b10 [61] was used to select the optimal evolution model by critically evaluating the selected parameters using the Akaike Information Criterion [62]. For the concatenated data and the wsp set, the submodel GTR+I+G was selected. Bayesian analyses were performed as implemented in MrBayes 3.1 [63]. Analyses were initiated from random starting trees. Four separate runs, each composed of four chains, were run for 6,000,000 generations. The cold chain was sampled every 100 generations, and the first 20,000 generations were discarded. Posterior probabilities were computed for the remaining trees. ML trees were constructed using MEGA 5.0 [64], with gamma distributed rates with 1000 bootstrap replications, and the method of Jukes and Cantor [65] as genetic distance model.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers. All MLST, wsp and 16S rRNA gene sequences generated in this study have been deposited into GenBank under accession numbers JF494842 to JF494922 and JF906102 to JF906107.

Results

Wolbachiainfection prevalence in different populations

The presence of Wolbachia was investigated in nine species within the three subgenera of Glossina. A total of 551 laboratory and 3199 field-collected adult flies, originating from 10 African countries, were tested using a Wolbachia specific 16S rRNA-based PCR assay (Table 1). The prevalence of Wolbachia infections differed significantly between the various populations of Glossina (Table 1). Wolbachia infections were detected in multiple species of the morsitans complex: G. m. morsitans, G. m. centralis, G. pallidipes and G. austeni, in the fusca complex in G. brevipalpis, while it was absent in the analysed species from the palpalis complex: G. p. palpalis, G. fuscipes and G. tachinoides. Wolbachia was also detected in just two out of 644 individuals of G. p. gambiensis.

Despite the heterogenous infections found in field populations, Wolbachia infection was fixed in the laboratory colonies of G. m. morsitans, and G. m. centralis. On the other hand, the infection was not fixed in laboratory colonies of G. brevipalpis and G. pallidipes and was completely absent from the laboratory colonies of the palpalis group species: G. p. palpalis, G. p. gambiensis, G. f. fuscipes and G. tachinoides.

Wolbachia prevalence ranged from 9.5 to 100% in natural populations of G. m. morsitans, from 52 to 100% in G. austeni, while it was only 2% in G. brevipalpis. Interestingly, previous studies on G. pallidipes and G. p. gambiensis natural populations did not observe any Wolbachia infection in these species. Our study did not find any evidence for Wolbachia infections in the screened natural populations of G. p. palpalis and G. f. fuscipes.

It is also interesting to note that the prevalence of Wolbachia infection was not homogenous and varied in different geographic populations for the same species. For example, the infection was fixed in natural populations of G. m. morsitans in Zambia and Tanzania while in Zimbabwe, two different sites exhibited 9.5% (Gokwe) and 100% (Kemukura) prevalence respectively.

Genotyping tsetse flies Wolbachiastrains

The bacterial strains present in each of the eleven Wolbachia-infected Glossina populations (seven natural and four laboratory), representing six species, were genotyped using MLST analysis (Table 2). A total of nine allelic profiles or Sequence Types (ST) was found in tsetse flies Wolbachia strains. All of them were new STs, based on the available data in the Wolbachia MLST database. The STs of the Wolbachia strains infecting the laboratory population of G. m. centralis and two out of the four natural populations of G. m. morsitans (12.3A, 32.3D) were identical. All Wolbachia strains infecting G. m. morsitans (except 24.4A) and G. m. centralis populations belong to the same sequencing complex, since they share at least three alleles. The MLST analysis showed the presence of seven gatB, seven coxA, four hcpA, seven ftsZ and four fbpA alleles. This analysis also revealed the presence of new alleles for all loci: five for gatB, four for coxA, two for hcpA, five for ftsZ and two for fbpA (Table 2).

The same eleven samples were also genotyped using the wsp gene: nine alleles were detected. For all tsetse flies Wolbachia strains, the WSP HVR profile, a combination of the four HVR amino acid haplotypes, was determined as described previously [41] (Table 3). A total of eight WSP HVR profiles were identified; six of them were new in the Wolbachia WSP database. The WSP HVR profile of the Wolbachia strains infecting (a) the natural population (12.3A) and the Yale lab colony (GmmY) of G. m. morsitans, (b) two natural populations of G. m. morsitans (32.3D and 30.9D) and (c) two natural populations of G. austeni (GauK and 05.2B) were identical. On the other hand, the Wolbachia strains infecting the KARI lab colony of G. m. morsitans (24.4A) as well as G. m. centralis (GmcY), G. pallidipes (15.5B), G. brevipalpis (09.7G) and G. p. gambiensis (405.11F) had unique WSP profiles. It is also interesting to note that three Wolbachia strains infecting G. m. morsitans (32.3D, 30.9D) and G. brevipalpis (09.7G) shared three HVR haplotypes (HVR2-4). Another triplet of strains infecting G. m. morsitans (32.3D, 30.9D and 24.4A) also shared three HVR haplotypes (HVR1, 2 and 4). The overall number of unique haplotypes per HVR varied. The WSP profile analysis showed the presence of seven HVR1, four HVR2, six HVR3 and five HVR4 haplotypes. The analysis also revealed the presence of new haplotypes: four for HVR1, two for HVR2, four HVR3 and one for HVR4 (Table 3).

Phylogenetic analysis

Phylogenetic analysis based on a concatenated dataset of all MLST loci revealed that the Wolbachia strains infecting G. m. morsitans, G. m. centralis, G. brevipalpis, G. pallidipes and G. austeni belong to supergroup A, while the Wolbachia strain infecting G. p. gambiensis fell into supergroup B (Fig. 1). The respective phylogenetic analysis based on the wsp gene dataset confirmed these results (Fig. 2). Phylogenetic reconstructions for concatenated alignments of MLST loci and wsp sequences showed similar results by both Bayesian inference and Maximum Likelihood methods. The Bayesian phylogenetic trees are presented in Figures 1 and 2 while the Maximum Likelihood trees are shown in Supplementary Figures 1 and 2 (Additional Files 2 and 3). The tsetse flies Wolbachia strains within the supergroup A form three different clusters. The first cluster includes the Wolbachia strains present in G. m. morsitans, G. m. centralis and G. brevipalpis. This cluster is closely related to Wolbachia strains infecting the fruit fly Drosophila bifasciata. The second cluster includes the Wolbachia strains infecting G. austeni populations and is distantly related to the strain present in Pheidole micula. The third cluster contains only the Wolbachia strain present in G. pallidipes and is closely related to Wolbachia strains present in Dipteran host species. The B-supergroup Wolbachia strain infecting G. p. gambiensis clusters with strains present in Tribolium confusum and Teleogryllus taiwanemma (Figs 1 and 2).

Bayesian inference phylogeny based on the concatenated MLST data (2,079 bp). The topology resulting from the Maximum Likelihood method was similar. The 11 Wolbachia strains present in Glossina are indicated in bold letters, and the other strains represent supergroups A, B, D, F and H. Strains are characterized by the names of their host species and ST number from the MLST database. Wolbachia supergroups are shown to the right of the host species names. Bayesian posterior probabilities (top numbers) and ML bootstrap values based on 1000 replicates (bottom numbers) are given (only values >50% are indicated).

Bayesian inference phylogeny based on the wsp sequence. The topology resulting from the Maximum Likelihood method was similar. The 11 Wolbachia strains present in Glossina are indicated in bold letters, and the other strains represent supergroups A, B, C, D and F. Strains are characterized by the names of their host species and their wsp allele number from the MLST database (except O. gibsoni for which the GenBank accession number is given). Wolbachia supergroups are shown to the right of the host species names. Bayesian posterior probabilities (top numbers) and ML bootstrap values based on 1000 replicates (bottom numbers) are given (only values >50% are indicated).

Horizontal transfer of Wolbachia genes to the G. m. morsitansgenome

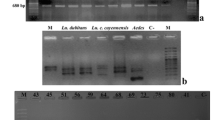

During the Wolbachia-specific 16S rRNA-based PCR screening of laboratory and natural G. m. morsitans populations, the presence of two distinct PCR amplification products was observed: one compatible with the expected size of 438 bp and a second smaller product of about 300 bp (Fig. 3a). Both PCR products were sequenced and confirmed to be of Wolbachia origin. The 438 bp product corresponded to the expected 16S rRNA gene fragment, while the shorter product contained a deletion of 142 bp (Fig. 3b). The 296 bp shorter version of the 16S rRNA gene was detected in all five individuals analyzed from G. m. morsitans colony individuals, as well as in DNA prepared from the tetracycline-treated (Wolbachia-free) G. m. morsitans samples, suggesting that it is of nuclear, and not cytoplasmic origin. This finding implies that the 16S rRNA gene segment was most likely transferred from the cytoplasmic Wolbachia to the G. m. morsitans genome, where it was pseudogenized through a deletion event. During the MLST analysis of the Wolbachia strain infecting G. m. morsitans, a similar phenomenon was observed for gene fbpA. PCR analysis showed the presence of two distict amplicons (Fig. 3a). Sequence analysis revealed that the larger 509 bp fragment was of the expected size, while the smaller fragment (453 bp in size) contained two deletions of 47 bp and 9 bp, respectively (Fig. 3b). The Wolbachia-free G. m. morsitans line contained only the smaller 453 bp version of the fbpA gene, suggesting again that this gene fragment is the result of a horizontal gene transfer event to the host chromosome.

Overview of deleted fragments in two Wolbachia genes A) PCR amplified products from G. m. morsitans (GmmY and Gtet) of the 16S rRNA and fbpA genes were resolved on 2.5% agarose gels stained with ethidium bromide. A 100-bp ladder was used as size standard. The input of the negative (neg) control was water. B) 16S rRNA and fbpA fragments from tsetse flies Wolbachia strains aligned with the corresponding regions of strain wMel. Red dashes represent the deletion region, the numbers show the positions before and after the deletions in respect to the wMel genome. The blue arrows represent the corresponding wMel genes. Deleted fragments were detected in G. m. morsitans samples (Gmormor: GmmY, 12.3A, 24.4A, 30.9D, 32.3D and Gtet). The right-left red arrows below the number indicate the size of deletion in base pairs.

Tissue specific detection of cytoplasmic and nuclear Wolbachiamarkers

The tissue specific distribution of the Wolbachia markers in G. m. morsitans were tested in ovary, salivary gland, midgut and carcass in normal and tetracycline-treated (Wolbachia-cured) flies. Two 16S rRNA PCR products (438 and 296 bp as described in Figure 3, corresponding to cytoplasmic and nuclear Wolbachia markers) could be amplified from ovary and testes tissues of uncured flies, while only the truncated 296 bp product that corresponds to the nuclear Wolbachia marker was amplified from all of the tissues (Figure 4). In contrast, the fragment that corresponds to the cytoplasmic 16S rRNA marker could not be amplified from any of the tissues of Wolbachia cured tetracycline-treated flies, including the reproductive organs (ovary and testes) (Fig. 4). The amplification of the larger product that corresponds to the cytoplasmic Wolbachia only from testes and ovary tissues of adults suggests that Wolbachia is restricted to the gonadal tissues in this species. Unlike for the 16S rRNA, a single wsp PCR product was observed in all tissues of Wolbachia infected and cured adults (Fig. 4). While it was not possible to differentiate between amplifications of cytoplasmic and nuclear Wolbachia, amplification from tetracycline treated adults suggests a horizontal transfer event also for the wsp gene. The size heterogeneity was also observed for fbpA. The larger 509 bp amplification which corresponds to the cytoplasmic marker was restricted to the reproductive tissues of the tsetse flies while the smaller derived 453 bp product corresponding to the nuclear marker was present in all tissues of infected and cured adults, suggesting horizontal transfer of fbpA to the G. m. morsitans genome (Fig. 4).

Tissue tropism of Wolbachia infections in G. m. morsitans. G. m. morsitans (GmmY and Gtet) PCR amplicons of genes 16S rRNA, wsp, and fbpA were resolved on a 2% agarose gel stained by ethidium bromide. The arrow with the solid line represents the cytoplasmic Wolbachia PCR product restricted to the reproductive tissues, and the arrow with the dashed line represents the PCR product found in all tissues tested. A 100 bp DNA ladder is used as size marker

Discussion

Prevalence of Wolbachia in Glossinaspecies

Our study suggests that Wolbachia infections are present in multiple species of the genus Glossina; however, the prevalence of infections in laboratory colonies versus natural populations and the Wolbachia strain harboured in the different species varies. The infection seems to be prevalent to the morsitans (savannah) group, which includes the species G. m. morsitans, G. m. centralis and G. austeni. In addition, uncured laboratory colonies largely show fixation, suggestive of active cytoplasmic incompatibility (Alam and Aksoy, personal communication). Wolbachia was also detected in the fusca (forest) group, which includes G. brevipalpis. In contrast, Wolbachia infection seems to be largely absent from the palpalis (riverine) group, which includes G. f. fuscipes, G. tachinoides and G. p. palpalis. It should be mentioned, however, that our results depend on the PCR-amplification conditions employed in this study and the presence of low density Wolbachia infections in these species, as has been reported for other insect species [66–68], cannot be excluded. Given that our screen was based on specimens collected during 1994-2010 (see Table 1), new screens should provide information on the dynamics of infection and the expression of cytoplasmic incompatibility.

The abovementioned data are in accordance with previous reports that detected Wolbachia in G. m. morsitans, G. m. centralis, G. brevipalpis and G. austeni [42, 43]. For the first time our study reports the presence of Wolbachia, albeit at very low prevalence, in G. pallidipes (morsitans group) and in G. p. gambiensis (palpalis group). The infection was only detected in 22 out of 1896 G. pallidipes and in 2 out of 644 G. p. gambiensis individuals; in both species, the infection was present in different populations, as shown in Table 1. Whether the presence of Wolbachia in these two species is a result of horizontal transfer, hybrid introgression or co-divergence in the morsitans and palpalis species complexes, as has recently been shown in other species complexes, has to await investigation [69–71].

The prevalence of Wolbachia was not homogenous among the different natural populations of G. m. morsitans. For example, in the area Gokwe (Zimbabwe), the infection prevalence was almost nine times lower than the average of the other areas. Glossina populations have been shown to exhibit extensive genetic structuring; of which the observed Wolbachia infection dynamics may be a result [72, 73]. Similar observations were made in G. austeni natural populations, where the Wolbachia infection was 98% in a South African population while the infection was 48% in a Kenyan population sampled in 1998 [42]. These data suggest that geography may influence Wolbachia prevalence as reported previously for field populations of spider Hylyphantes graminicola [74]. Further research on the heterogeneous distribution of Wolbachia infection in field populations could shed more light on the functional role of this endosymbiont in tsetse flies biology, ecology and evolution.

Genotyping - phylogeny

The MLST- and wsp-based sequence analysis indicates that all but one of the Wolbachia strains infecting Glossina species belong to supergroup A; the exception being the bacterial strain infecting G. p. gambiensis, which belongs to supergroup B. The supergroup A tsetse flies Wolbachia strains are members of three separate and distantly related groups. Our results are in accordance with two previous studies that relied on just the wsp phylogeny but indicated a similar topology [42, 44]. The phylogenetic analyses strongly suggest the presence of distantly related Wolbachia strains in tsetse flies species and support the hypothesis that horizontal transmission of Wolbachia between insect species from unrelated taxa has extensively occurred, as has been reported in the spider genus Agelenopsis [70], in the wasp genus Nasonia [71], in the acari genus Bryobia [40] and in the termites of genus Odontotermes [75]. On the other hand, the sibling species G. m. morsitans and G. m. centralis carry closely related Wolbachia strains, which have identical ST and differ only in the sequence of the fast evolving wsp gene, which suggests host-symbiont co-divergence. In addition, field populations of G. m. morsitans from different locations of Africa harbor very closely related Wolbachia strains, suggesting that the geographical origin of their hosts did not impact significantly Wolbachia strain divergence. Our findings are in agreement with reports on dipteran hosts associated with mushrooms [76] and on the spider Hylyphantes graminicola [74]. On the other hand, studies on fig wasps [77] and ants [78] showed considerable association between biogeography and strain similarity.

Horizontal gene transfer

The evolutionary fate of any host-bacterial symbiotic association depends on the modes of transmission of the bacterial partner, vertical, horizontal or both. Additionally, horizontal gene (or genome) transfer events may also be important. Our data suggest that at least three genes (16S rRNA, fbpA and wsp) of the Wolbachia strain infecting G. m. morsitans have been transferred to the host genome (Figures 3 and 4). This transfer is supported by the amplification of derivative copies of fbpA and 16S rRNA, and of wsp in tissues from tetracycline-treated G. m. morsitans (Figure 4). The results suggest that fbpA and 16S rRNA have been pseudogenized through the accumulation of deletions, consistent with previous studies [45, 46, 51]. The transfer events were detected both in laboratory and natural populations, suggesting that they are the result of the long co-evolution of the host-Wolbachia associations. Interestingly, neither cytoplasmic Wolbachia infections nor chromosomal insertions were detected in the sibling species G. m. centralis, suggesting that the horizontal transfer event took place after the divergence of these two species. Our preliminary and ongoing studies indicate that chromosomal insertions with Wolbachia sequences may be more extensive than reported here (Aksoy and Bourtzis, unpublished observations). Similar horizontal transfer events have been reported for other Wolbachia-infected hosts [45–52]. It is worth noting that in some cases, horizontally transferred Wolbachia genes are expressed from the host genome, as reported in the mosquito Aedes aegypti and in the pea aphid Acyrthosiphon pisum, where the Wolbachia-like genes are expressed in salivary glands and in the bacteriocyte, respectively [48–50]. The release of the G. morsitans morsitans genome will allow us to further examine, by both in silico and molecular analysis, the extent of the horizontal gene transfer of the Wolbachia sequences into the tsetse fly nuclear genome and whether these genes are expressed.

Conclusions

Wolbachia is present in both laboratory and natural populations of Glossina species. Tsetse flies Wolbachia strains were characterized based on 16S rRNA, wsp and MLST gene markers. In addition, horizontal gene transfer events of Wolbachia genes into tsetse fly chromosomes were detected and characterized. The detailed characterization of Wolbachia infections is a crucial step towards an adequate understanding of tsetse flies-Wolbachia interactions, which is essential for the development and implementation of Wolbachia-based biological control approaches.

References

Werren JH: Biology of Wolbachia. Annu Rev Entomol. 1997, 42: 587-609. 10.1146/annurev.ento.42.1.587.

Werren JH, Windsor DM: Wolbachia infection frequencies in insects: evidence of a global equilibrium?. Proc Biol Sci. 2000, 267 (1450): 1277-1285. 10.1098/rspb.2000.1139.

Jeyaprakash A, Hoy MA: Long PCR improves Wolbachia DNA amplification: wsp sequences found in 76% of sixty-three arthropod species. Insect Mol Biol. 2000, 9 (4): 393-405. 10.1046/j.1365-2583.2000.00203.x.

Hilgenboecker K, Hammerstein P, Schlattmann P, Telschow A, Werren JH: How many species are infected with Wolbachia?-A statistical analysis of current data. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2008, 281 (2): 215-220. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01110.x.

Bandi C, Anderson TJ, Genchi C, Blaxter ML: Phylogeny of Wolbachia in filarial nematodes. Proc Biol Sci. 1998, 265 (1413): 2407-2413. 10.1098/rspb.1998.0591.

Bourtzis K, O'Neill S: Wolbachia infections and arthropod reproduction - Wolbachia can cause cytoplasmic incompatibility, parthenogenesis, and feminization in many arthropods. Bioscience. 1998, 48 (4): 287-293. 10.2307/1313355.

Werren JH, Baldo L, Clark ME: Wolbachia: master manipulators of invertebrate biology. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008, 6 (10): 741-751. 10.1038/nrmicro1969.

Stouthamer R, Breeuwer JA, Hurst GD: Wolbachia pipientis: microbial manipulator of arthropod reproduction. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1999, 53: 71-102. 10.1146/annurev.micro.53.1.71.

Bourtzis K, Miller TA: Insect Symbiosis. 2003, Florida, USA: CRC Press

Saridaki A, Bourtzis K: Wolbachia: more than just a bug in insects genitals. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2010, 13 (1): 67-72. 10.1016/j.mib.2009.11.005.

Hurst G, Jiggins F, Majerus M: Inherited microorganisms that selectively kill male hosts: the hidden players of insect evolution?. Insect Symbiosis. Edited by: Bourtzis K, Miller TA. 2003, Florida: CRC Press, 177-197.

Taylor MJ, Bandi C, Hoerauf A: Wolbachia bacterial endosymbionts of filarial nematodes. Adv Parasitol. 2005, 60: 245-284.

Bandi C, Dunn AM, Hurst GD, Rigaud T: Inherited microorganisms, sex-specific virulence and reproductive parasitism. Trends Parasitol. 2001, 17 (2): 88-94. 10.1016/S1471-4922(00)01812-2.

Dedeine F, Bandi C, Bouletreau M, Kramer L: Insights into Wolbachia obligatory symbiosis. Insect Symbiosis. Edited by: Bourtzis K, Miller TA. 2003, Florida: CRC PRESS, 267-282.

Kambris Z, Cook PE, Phuc HK, Sinkins SP: Immune activation by life-shortening Wolbachia and reduced filarial competence in mosquitoes. Science. 2009, 326 (5949): 134-136. 10.1126/science.1177531.

Moreira LA, Iturbe-Ormaetxe I, Jeffery JA, Lu G, Pyke AT, Hedges LM, Rocha BC, Hall-Mendelin S, Day A, Riegler M, et al: A Wolbachia symbiont in Aedes aegypti limits infection with dengue, Chikungunya, and Plasmodium. Cell. 2009, 139 (7): 1268-1278. 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.042.

Pfarr K, Hoerauf A: The annotated genome of Wolbachia from the filarial nematode Brugia malayi: what it means for progress in antifilarial medicine. PLoS Med. 2005, 2 (4): e110-10.1371/journal.pmed.0020110.

Zabalou S, Riegler M, Theodorakopoulou M, Stauffer C, Savakis C, Bourtzis K: Wolbachia-induced cytoplasmic incompatibility as a means for insect pest population control. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004, 101 (42): 15042-15045. 10.1073/pnas.0403853101.

Beard CB, Durvasula RV, Richards FF: Bacterial symbiosis in arthropods and the control of disease transmission. Emerg Infect Dis. 1998, 4 (4): 581-591. 10.3201/eid0404.980408.

McMeniman CJ, Lane RV, Cass BN, Fong AW, Sidhu M, Wang YF, O'Neill SL: Stable introduction of a life-shortening Wolbachia infection into the mosquito Aedes aegypti. Science. 2009, 323 (5910): 141-144. 10.1126/science.1165326.

Xi Z, Khoo CC, Dobson SL: Wolbachia establishment and invasion in an Aedes aegypti laboratory population. Science. 2005, 310 (5746): 326-328. 10.1126/science.1117607.

Bourtzis K: Wolbachia-based technologies for insect pest population control. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2008, 627: 104-113. 10.1007/978-0-387-78225-6_9.

Welburn SC, Fevre EM, Coleman PG, Odiit M, Maudlin I: Sleeping sickness: a tale of two diseases. Trends Parasitol. 2001, 17 (1): 19-24. 10.1016/S1471-4922(00)01839-0.

Cattand P: The scourge of human African trypanosomiasis. Afr Health. 1995, 17 (5): 9-11.

Kioy D, Jannin J, Mattock N: Human African trypanosomiasis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004, 2 (3): 186-187.

Simarro PP, Diarra A, Ruiz Postigo JA, Franco JR, Jannin JG: The human African trypanosomiasis control and surveillance programme of the world health organization 2000-2009: the way forward. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011, 5 (2): e1007-10.1371/journal.pntd.0001007.

Aksoy S: Sleeping sickness elimination in sight: time to celebrate and reflect, but not relax. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011, 5 (2): e1008-10.1371/journal.pntd.0001008.

Zabalou S, Apostolaki A, Livadaras I, Franz G, Robinson AS, Savakis C, Bourtzis K: Incompatible insect technique: incompatible males from a Ceratitis capitata genetic sexing strain. Entomologia Experimentalis Et Applicata. 2009, 132 (3): 232-240. 10.1111/j.1570-7458.2009.00886.x.

Bourtzis K, Robinson AS: Insect pest control using Wolbachia and/or radiation. Insect Symbiosis 2. Edited by: Bourtzis K, Miller TA. 2006, Florida, USA: CRC Press, Talylor and Francis Group, LLC, 225-246.

Apostolaki A, Saridaki A, Livadaras I, Savakis C, Bourtzis K: Transinfection of the olive fruit fly with a Wolbachia CI inducing strain: a promising symbiont-based population control strategy?. Journal of Applied Entomology. 2011, 10.1111/j.1439-0418.2011.01614.x

Cheng Q, Aksoy S: Tissue tropism, transmission and expression of foreign genes in vivo in midgut symbionts of tsetse flies. Insect Mol Biol. 1999, 8 (1): 125-132. 10.1046/j.1365-2583.1999.810125.x.

Rio R, Hu Y, Aksoy S: Strategies of the home-team: symbioses exploited for vector-borne disease control. Trends Microbiology. 2004, 12 (7): 325-336. 10.1016/j.tim.2004.05.001.

Aksoy S, Rio RV: Interactions among multiple genomes: tsetse, its symbionts and trypanosomes. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2005, 35 (7): 691-698. 10.1016/j.ibmb.2005.02.012.

Lo N, Casiraghi M, Salati E, Bazzocchi C, Bandi C: How many Wolbachia supergroups exist?. Mol Biol Evol. 2002, 19 (3): 341-346. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004087.

Lo N, Paraskevopoulos C, Bourtzis K, O'Neill SL, Werren JH, Bordenstein SR, Bandi C: Taxonomic status of the intracellular bacterium Wolbachia pipientis. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2007, 57 (Pt 3): 654-657.

Rowley SM, Raven RJ, McGraw EA: Wolbachia pipientis in Australian spiders. Curr Microbiol. 2004, 49 (3): 208-214.

Bordenstein S, Rosengaus RB: Discovery of a novel Wolbachia super group in Isoptera. Curr Microbiol. 2005, 51 (6): 393-398. 10.1007/s00284-005-0084-0.

Casiraghi M, Bordenstein SR, Baldo L, Lo N, Beninati T, Wernegreen JJ, Werren JH, Bandi C: Phylogeny of Wolbachia pipientis based on gltA, groEL and ftsZ gene sequences: clustering of arthropod and nematode symbionts in the F supergroup, and evidence for further diversity in the Wolbachia tree. Microbiology. 2005, 151 (Pt 12): 4015-4022.

Gorham CH, Fang QQ, Durden LA: Wolbachia endosymbionts in fleas (Siphonaptera). J Parasitol. 2003, 89 (2): 283-289. 10.1645/0022-3395(2003)089[0283:WEIFS]2.0.CO;2.

Ros VI, Fleming VM, Feil EJ, Breeuwer JA: How diverse is the genus Wolbachia? Multiple-gene sequencing reveals a putatively new Wolbachia supergroup recovered from spider mites (Acari: Tetranychidae). Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009, 75 (4): 1036-1043. 10.1128/AEM.01109-08.

Baldo L, Dunning Hotopp JC, Jolley KA, Bordenstein SR, Biber SA, Choudhury RR, Hayashi C, Maiden MC, Tettelin H, Werren JH: Multilocus sequence typing system for the endosymbiont Wolbachia pipientis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006, 72 (11): 7098-7110. 10.1128/AEM.00731-06.

Cheng Q, Ruel TD, Zhou W, Moloo SK, Majiwa P, O'Neill SL, Aksoy S: Tissue distribution and prevalence of Wolbachia infections in tsetse flies, Glossina spp. Med Vet Entomol. 2000, 14 (1): 44-50. 10.1046/j.1365-2915.2000.00202.x.

O'Neill SL, Gooding RH, Aksoy S: Phylogenetically distant symbiotic microorganisms reside in Glossina midgut and ovary tissues. Med Vet Entomol. 1993, 7 (4): 377-383. 10.1111/j.1365-2915.1993.tb00709.x.

Zhou W, Rousset F, O'Neil S: Phylogeny and PCR-based classification of Wolbachia strains using wsp gene sequences. Proc Biol Sci. 1998, 265 (1395): 509-515. 10.1098/rspb.1998.0324.

Kondo N, Nikoh N, Ijichi N, Shimada M, Fukatsu T: Genome fragment of Wolbachia endosymbiont transferred to X chromosome of host insect. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002, 99 (22): 14280-14285. 10.1073/pnas.222228199.

Nikoh N, Tanaka K, Shibata F, Kondo N, Hizume M, Shimada M, Fukatsu T: Wolbachia genome integrated in an insect chromosome: evolution and fate of laterally transferred endosymbiont genes. Genome Res. 2008, 18 (2): 272-280. 10.1101/gr.7144908.

Dunning Hotopp JC, Clark ME, Oliveira DC, Foster JM, Fischer P, Munoz Torres MC, Giebel JD, Kumar N, Ishmael N, Wang S, et al: Widespread lateral gene transfer from intracellular bacteria to multicellular eukaryotes. Science. 2007, 317 (5845): 1753-1756. 10.1126/science.1142490.

Klasson L, Kambris Z, Cook PE, Walker T, Sinkins SP: Horizontal gene transfer between Wolbachia and the mosquito Aedes aegypti. BMC Genomics. 2009, 10: 33-10.1186/1471-2164-10-33.

Woolfit M, Iturbe-Ormaetxe I, McGraw EA, O'Neill SL: An ancient horizontal gene transfer between mosquito and the endosymbiotic bacterium Wolbachia pipientis. Mol Biol Evol. 2009, 26 (2): 367-374. 10.1093/molbev/msn253.

Nikoh N, Nakabachi A: Aphids acquired symbiotic genes via lateral gene transfer. BMC Biol. 2009, 7: 12-10.1186/1741-7007-7-12.

Aikawa T, Anbutsu H, Nikoh N, Kikuchi T, Shibata F, Fukatsu T: Longicorn beetle that vectors pinewood nematode carries many Wolbachia genes on an autosome. Proc Biol Sci. 2009, 276 (1674): 3791-3798. 10.1098/rspb.2009.1022.

Fenn K, Conlon C, Jones M, Quail MA, Holroyd NE, Parkhill J, Blaxter M: Phylogenetic relationships of the Wolbachia of nematodes and arthropods. PLoS Pathog. 2006, 2 (10): e94-10.1371/journal.ppat.0020094.

Abd-Alla A, Bossin H, Cousserans F, Parker A, Bergoin M, Robinson A: Development of a non-destructive PCR method for detection of the salivary gland hypertrophy virus (SGHV) in tsetse flies. J Virol Methods. 2007, 139 (2): 143-149. 10.1016/j.jviromet.2006.09.018.

Doyle JJ, Doyle JL: Isolation of plant DNA from fresh tissue. Focus. 1990, 12: 13-15.

Hanner R, Fugate M: Branchiopod phylogenetic reconstruction from 12S rDNA sequence data. Journal of Crustacean Biology. 1997, 17 (1): 174-183. 10.2307/1549471.

Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T: Molecular cloning. 1989, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 2nd

Braig HR, Zhou W, Dobson SL, O'Neill SL: Cloning and characterization of a gene encoding the major surface protein of the bacterial endosymbiont Wolbachia pipientis. J Bacteriol. 1998, 180 (9): 2373-2378.

Edgar RC: MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32 (5): 1792-1797. 10.1093/nar/gkh340.

Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ: CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994, 22 (22): 4673-4680. 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673.

Geneious v4.0. [http://www.geneious.com/]

Swofford DL: PAUP: phylogenetic analysis using parsimony, 4.0, beta version 4a ed. 2000, Sunderland, Md.: Sinauer Associates

Akaike H: New Look at Statistical-Model Identification. AcIeee Transactions on Automatic Control. 1974, 19 (6): 716-723. 10.1109/TAC.1974.1100705.

Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP: MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2003, 19 (12): 1572-1574. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180.

Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S: MEGA5: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2011,

Jukes TH, Cantor CR: Evolution of protein molecules. Mammalian Protein Metabolism. Edited by: Munro HN. 1969, New York: Academic Press, 21-132.

Simoes PM, Mialdea G, Reiss D, Sagot M-F, Charlat S: Wolbachiadetection: an assessment of standard PCR Protocols. Molecular Ecology Resources. 2011,

Miller WJ, Ehrman L, Schneider D: Infectious speciation revisited: impact of symbiont-depletion on female fitness and mating behavior of Drosophila paulistorum. PLoS Pathog. 2010, 6 (12): e1001214-10.1371/journal.ppat.1001214.

Arthofer W, Riegler M, Schneider D, Krammer M, Miller WJ, Stauffer C: Hidden Wolbachia diversity in field populations of the European cherry fruit fly, Rhagoletis cerasi (Diptera, Tephritidae). Mol Ecol. 2009, 18 (18): 3816-3830. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04321.x.

Baldo L, Bordenstein S, Wernegreen JJ, Werren JH: Widespread recombination throughout Wolbachia genomes. Mol Biol Evol. 2006, 23 (2): 437-449.

Baldo L, Ayoub NA, Hayashi CY, Russell JA, Stahlhut JK, Werren JH: Insight into the routes of Wolbachia invasion: high levels of horizontal transfer in the spider genus Agelenopsis revealed by Wolbachia strain and mitochondrial DNA diversity. Mol Ecol. 2008, 17 (2): 557-569.

Raychoudhury R, Baldo L, Oliveira DC, Werren JH: Modes of acquisition of Wolbachia: horizontal transfer, hybrid introgression, and codivergence in the Nasonia species complex. Evolution. 2009, 63 (1): 165-183. 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00533.x.

Ouma JO, Marquez JG, Krafsur ES: Patterns of genetic diversity and differentiation in the tsetse fly Glossina morsitans morsitans Westwood populations in East and southern Africa. Genetica. 2007, 130 (2): 139-151. 10.1007/s10709-006-9001-0.

Krafsur ES: Tsetse flies: genetics, evolution, and role as vectors. Infect Genet Evol. 2009, 9 (1): 124-141. 10.1016/j.meegid.2008.09.010.

Yun Y, Lei C, Peng Y, Liu F, Chen J, Chen L: Wolbachia strains typing in different geographic population spider, Hylyphantes graminicola (Linyphiidae). Curr Microbiol. 2010, 62 (1): 139-145.

Salunke BK, Salunkhe RC, Dhotre DP, Khandagale AB, Walujkar SA, Kirwale GS, Ghate HV, Patole MS, Shouche YS: Diversity of Wolbachia in Odontotermes spp. (Termitidae) and Coptotermes heimi (Rhinotermitidae) using the multigene approach. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2010, 307 (1): 55-64. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2010.01960.x.

Stahlhut JK, Desjardins CA, Clark ME, Baldo L, Russell JA, Werren JH, Jaenike J: The mushroom habitat as an ecological arena for global exchange of Wolbachia. Mol Ecol. 2010, 19 (9): 1940-1952. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04572.x.

Haine ER, Cook JM: Convergent incidences of Wolbachia infection in fig wasp communities from two continents. Proc Biol Sci. 2005, 272 (1561): 421-429. 10.1098/rspb.2004.2956.

Russell JA, Goldman-Huertas B, Moreau CS, Baldo L, Stahlhut JK, Werren JH, Pierce NE: Specialization and geographic isolation among Wolbachia symbionts from ants and lycaenid butterflies. Evolution. 2009, 63 (3): 624-640. 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00579.x.

Acknowledgements and funding

This work was co-funded by the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme CSA-SA_REGPROT-2007-1 under grant agreement no 203590 and CSA-SA REGPOT-2008-2 under grant agreement 245746. We are also grateful to FAO/IAEA Coordinated Research Program “Improving SIT for Tsetse Flies through Research on their Symbionts” and to EU COST Action FA0701 “Arthropod Symbiosis: From Fundamental Studies to Pest and Disease Management”. This study also received support from National Institutes of Health grants AI06892, D43TW007391, R03TW008413 and Monell Foundation awarded to SA. We also thank Drs. Jan Van Den Abbeele, Andrew Chamisa, Antony Chupa, Berisha Kapitano, Karen Kappmeier-Green, Stephan Kkilaui, Imna Malele, Sadou Miga, Alan Robinson, Loyce Okedi and Hasanq Tanqa for providing tsetse flies samples and Gisele Oudrougou and Abdul Hasim Mohamed for their technical help with DNA extraction.

This article has been published as part of BMC Microbiology Volume 11 Supplement 1, 2012: Arthropod symbioses: from fundamental studies to pest and disease mangement. The full contents of the supplement are available online at http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2180/12?issue=S1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors' contributions

Conceived and designed experiments: Abd-Alla Adly, Serap Aksoy, Kostas Bourtzis

Experimental work: Vangelis Doudoumis, George Tsiamis, Florence Wamwiri, Corey Brelsfoard, Uzma Alam, Emre Aksoy, Stelios Dalaperas, Abd-Alla Adly

Data analysis: Vangelis Doudoumis, George Tsiamis, Corey Brelsfoard, Aksoy Serap, Kostas Bourtzis

Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: Johnson Ouma, Peter Takac

Manuscript writing and editing: Vangelis Doudoumis, George Tsiamis, Corey Brelsfoard, Abd-Alla Adly, Aksoy Serap, Kostas Bourtzis

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Electronic supplementary material

12866_2012_1548_MOESM2_ESM.jpg

Additional file 2: Supplementary Figure 1: Maximum likelihood inference phylogeny based on the concatenated MLST data, 2,079 bp. (Please note that tree has been rooted to the supergroup D sequences). (JPG 99 KB)

12866_2012_1548_MOESM3_ESM.jpg

Additional file 3: Supplementary Figure 2: Maximum likelihood inference phylogeny based on the on the wsp sequence. (Please note that tree has been rooted to the supergroup D sequences). (JPG 124 KB)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Doudoumis, V., Tsiamis, G., Wamwiri, F. et al. Detection and characterization of Wolbachia infections in laboratory and natural populations of different species of tsetse flies (genus Glossina). BMC Microbiol 12 (Suppl 1), S3 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2180-12-S1-S3

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2180-12-S1-S3