Abstract

Background

The protozoan Trypanosoma cruzi circulates in semiarid areas of northeastern Brazil in distinct ecotopes (sylvatic, peridomestic and domestic) where Triatoma brasiliensis Neiva, 1911 is the most important Chagas disease vector. In this study, we analyzed microevolutionary and demographic aspects of T. brasiliensis populations at the ecotypic, micro and macro-geographic scales by combining morphometrics and molecular results. Additionally, we aimed to address the resolution of both markers for delimiting populations in distinct scales.

Methods

We sampled populations of T. brasiliensis from distinct ecotypic and geographic sites in the states Rio Grande do Norte (RN) and Paraíba (PB). The geometric morphometry was carried out with 13 landmarks on the right wings (n = 698) and the genetic structure was assessed by sequencing a region of cytochrome b mitochondrial gene (n = 221). Mahalanobis distance (MD) and coefficient of molecular differentiation (ΦST) were calculated among all pairs of populations. The results of comparisons generated MD and ΦST dendrograms, and graphics of canonical variate analysis (CVA).

Results

Little structure was observed for both markers for macro-geographic scales. Mantel tests comparing geographic, morphometric and genetic matrices showed low correlation (all R2 < 0.35). The factorial graphics built with the CVA evidenced population delimitation for the morphometric data at micro-geographic scales.

Conclusions

We believe that T. brasiliensis carries in its genotype a source of information to allow the phenotypical plasticity across its whole distribution for shaping populations, which may have caused a lack of population delimitation for CVAs in morphometric analysis for macro-geographic scale analysis. On the other hand, the pattern of morphometric results in micro-geographic scales showed well-defined groups, highlighting the potential of this tool to inferences on the source for infestation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Chagas disease is among the most important neglected diseases in Latin American countries. The transmission classically occurs via vector insects of the subfamily Triatominae (Hemiptera: Heteroptera: Reduviidae). These insect vectors may transmit the disease when they are infected with the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi (Chagas, 1909) (Kinetoplastida: Trypanosomatidae), the etiological agent of the illness. Although the disease’s incidence has declined in recent decades due to intense programs to combat the main domiciliated vectors, it is estimated that six to eight million people are still infected worldwide [1].

More than 65 species of triatomines have been recorded in Brazil, but few exhibit synanthropic behaviors, such as Triatoma infestans, Panstrongylus megistus (Burmeister, 1835), T. brasiliensis Neiva, 1911, T. pseudomaculata Corrêa & Espínola, 1964 and T. sordida (Stål, 1859) [2]. The Brazilian Northeast, one of the poorest and underdeveloped regions of the country, raises concern in the context of Chagas disease transmission because it is an area of infestation by T. brasiliensis and T. pseudomaculata, native triatomines of difficult control and widespread in the semiarid Northeast. Whereas T. pseudomaculata is more associated with birds [3] (refractory to T. cruzi infection), T. brasiliensis is associated with mammals, which are potential parasite reservoirs [4, 5]. Additionally, T. brasiliensis is the most frequently Chagas disease vector collected in human domiciles and is considered the most important triatomine species in the region [6].

The current status of the T. brasiliensis species complex is based on a group of monophyletic taxa that occur in rocky outcrops of the semiarid region of the Brazilian Northeast, including seven species: T. brasiliensis; T. bahiensis Sherlock & Serafim, 1967; T. juazeirensis Costa & Felix, 2007; T. lenti Sherlock & Serafim, 1967; T. melanica (Neiva & Lent, 1941); T. petrocchiae Pinto & Barreto, 1925; and T. sherlocki Papa, Jurberg, Carcavallo, Cerqueira & Barata, 2002; in which T. brasiliensis is divided into two subspecies: T. b. brasiliensis Neiva, 1911 and T. b. macromelasoma Galvão, 1956 [7]. Lent & Wygodzinsky [8] observed that across its distribution, T. brasiliensis (s.l.) exhibited numerous chromatic forms and emphasized it should be better investigated. This led Costa and colleagues to conduct a set of investigations based on biology, ecology, phylogeny, experimental crossings [9,10,11,12,13] among others. The Brasiliensis subcomplex was proposed by Schofield & Galvão [14] based on the ecological data, geographical distribution and morphology, which included T. melanocephala Neiva & Pinto, 1923 and T. vitticeps (Stal, 1859) (as uncertain). The chromatic variation combined with genetic information resulted in raising T. juazeirensis [15] and T. melanica [16] to the specific taxonomic status. One variation presenting intermediate forms was considered subspecies (T. b. macromelasoma), also because little genetic distance was observed with T. b. brasiliensis [17]. Later, T. sherlocki was included in this species complex by using the information on the variation in cytochrome b (cytb) and 16S mitochondrial genes [18], which was confirmed through cytogenetic analyzes and experimental crosses [19, 20]. Other species were included in this group or revalidated, such as T. lenti and T. bahiensis [21]. Finally, T. petrocchiae was also considered a member of this monophyletic group, in a study combining geometric morphometrics and information on multiple mitochondrial genes (12S + 16S + cox1 + cytb) [22]. The non-monophyly of the Brasiliensis subcomplex also proposed the exclusion of T. melanocephala and T. vitticeps [22], which was then confirmed through cytogenetic analyzes [23, 24]. Recently, a key was released to identify each member of this species complex [7]. For simplicity, we hereafter refer to the taxon used in this study (T. b. brasiliensis) as T. brasiliensis.

For the T. brasiliensis species complex, molecular studies have been mainly based on the variation of mitochondrial DNA genes [5, 17, 25] and, geometric morphometrics has already been applied for the species [26]. Molecular and morphometric markers have been combined [22, 27], but not under the focus of gamma systematics (intra-specifically). In this study, we analyzed microevolutionary and demographic aspects of T. brasiliensis populations at the ecotypic, micro and macro-geographical scales by combining morphometrics and molecular approaches.

Methods

Insects

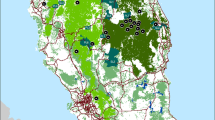

Triatomine captures were conducted in the State of Rio Grande do Norte (RN), in the municipalities of Caicó, Currais Novos and Marcelino Vieira, whereas in the State of Paraíba (PB), insects were collected in the municipalities of Condado, Cajazeiras, Santa Teresinha, São José de Espinharas, São Mamede and Emas (Fig. 1). The sampling covered a range of 240 km (East-West) and 95 km (North-South) (− 6°58′48.0″ to − 6°08′49.2″ latitude and − 38°35′27.6″ to − 36°29′09.6″ longitude). The sampled spots were within the biogeographical zone known as Caatinga, a mosaic of xerophytic, deciduous, semiarid thorn scrub and forest [28]. All captures were conducted manually with the aid of tweezers. We defined three distinct ecotopes: (i) the sylvatic ecotopes (primary) were represented by rocky outcrops; (ii) the domestic ecotopes were considered as the indoor spaces where humans sleep or work; and (iii) the peridomestic ecotopes were defined as the spaces surrounding domiciles, where domesticated animals sleep or are raised. In peridomiciles, most of the triatomines were captured in stone/woodpiles, chicken coops and goat and pig corrals. Captured specimens were identified according to taxonomic keys [7, 8, 24]. The insects were individually labeled and stored in 1.5 ml microtubes with 100% ethanol. The wings were kept dry in another tube with the same label for the ones in ethanol. In the laboratory, all tubes were stored at < 5 °C.

Localities (in gray) where the collections were made in the states of Rio Grande do Norte (RN) and Paraíba (PB), Brazil: Caicó-RN (CC), Condado-PB (CD), Currais Novos-RN (CN), Cajazeiras-PB (CZ), Emas-PB (EM), Marcelino Vieira-RN (MV), Santa Teresinha-PB (ST), São José de Espinharas-PB (SJ) and São Mamede-PB (SM)

Population definition

We based the population defined as the set of insects collected at the same site and capture spot. Each insect/wing was cataloged at the population level, receiving identification acronyms, namely: (i) the first two letters refer to the locality: Caicó-RN (CC); Currais Novos-RN (CN); Marcelino Vieira-RN (MV); Condado-PB (CD); Cajazeiras-PB (CZ); Santa Teresinha-PB (ST); São José de Espinharas-PB (SJ); São Mamede-PB (SM); and Emas-PB (EM) (Fig. 1); (ii) geographical coordinate (two/three numbers); (iii) ecotope: wild (S); peridomestic (P); and domestic (D); and (iv) sex: male (M); and female (F). Morphometrics and molecular analyses were carried out for the same populations.

Morphometric analysis

For this study, the anterior wing of 5–30 individuals per population was used. Considering the epidemiological importance, we did not exclude populations with lower numbers, as for the bug collected inside domiciles in Condado-PB. Photographic records of right wings were made using a stereomicroscope Zeiss™ Discovery V.12 (Göttingen, Germany) with the image capture system AxioCam 5.0™ and ZEN™ software version 2.0 (Carl Zeiss, SteREO Discovery). Thirteen anatomical landmarks (Fig. 2) were used via TPS dig 2.17 [29]. To reduce the user effect, the same operator marked all landmarks. Additionally, the wing images of each sex were mixed and picked up randomly before capturing the landmarks.

The shape variables were obtained by using the generalized Procrustes superposition algorithm and the subsequent projection of the Procrustes residues were defined in an Euclidean space. Both non-uniform and uniform components were used as shape variables [30]. These two components describe the differences in deviations from an average reference point configuration [31]. The centroid size of the isometric estimator (CS) derived from the analysis based on anatomical landmarks was used as a measure of the overall size [29,30,31,32,33].

For shape measurements, Mahalanobis distances (MD) between all pairs of populations were calculated and their significance was assessed using a non-parametric test based on permutations (10,000 simulations), which were illustrated in dendrograms. The choice for MD instead of Procrustes distances (PD) was based on some studies that say that PD produces estimates that are statistically inconsistent if the variation is not isotropic [34,35,36]. Additionally, pilot runs showed little difference between PD and MD. The percentage of phenotypic similarity between pairs of populations was calculated using a cross-validation test, which evidences the percentages of individuals that were correctly assigned to their populations. The relationship between centroid size (CS) and discrimination of shapes between groups (allometry) was estimated through a multivariate regression between the coordinates of Procrustes (dependent variables) and CS (independent variable). This analysis was performed for each module and among populations/population groups. These regressions show associations in all comparisons via random permutations. The degree of differentiation between individuals was illustrated through graphics of principal components analysis (PCA) and canonical variate analysis (CVA), which were assessed by the combination of variations in the 13 anatomical coordinates of each individual. All of these statistics were performed using the MorphoJ software [33]. P-values were considered significant at P < 0.05.

Molecular analysis

The total DNA of 3 legs was extracted using the Qiagen Blood and Tissue kit (Valencia, CA, USA), following the manufacturer’s specifications. The mitochondrial cytochrome b (cytb) gene was amplified by the polymerase chain reaction (PCR), using the primer pair CYTB7432F, and CYTBR and amplification conditions set by the authors who designed the primers [37, 38]. Both strands (forward and reverse) were sequenced by using the purifications and sequencing reactions defined in [37, 38]. Forward and reverse sequences were assembled into contigs for editing [39]. Edited sequences were compared to those in the GenBank database using the BLAST [40] program to check the specific status. Sequences were trimmed to 447 bp so as they were of equal length. A phylogram was built with the resulting cytb sequences via Bayesian inference with unique haplotypes. The matrix was run in BEAST 1.8.0 [41] with 10 million generations and sampling every 1000 simulations. A strict molecular clock model (with a default rate of 1.0) and the constant-size coalescent tree prior were applied for this analysis. Tracer 1.7 [42] was used to check parameter convergence with a stationary state, using a minimum threshold for ESS (effective sample size) value of 200. TreeAnnotator (available in the BEAST package) was used to summarize all the generated trees with the highest credibility, being visualized and edited using FigTree 1.4.4 (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/). The evolutionary model was chosen according to the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) in MrModeltest [43]. Estimates of evolutionary divergence between sequences were based on Kimura 2-parameter model (K2P) [44] by using MEGA-X software [45].

For population analysis, summary statistics of genetic diversity of T. brasiliensis were calculated for insects from each population. The null hypothesis of neutrality was tested using Tajima’s D statistic [46] and Fu’s Fs [47]. The following population genetic summary statistics were calculated; number of haplotypes (H), haplotype diversity (Hd) and nucleotide diversity (π). A hierarchical analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) [48] was performed to access the population’s genetic structure. DnaSP v6 software [49] was used to generate the files to run the analyses described above in Arlequin 3.5 [50] software. The significance of molecular statistics (Haplotype diversity, Pi [π], Fu’s, Tajima’s D) [46] was tested using 1,000 permutations, being considered significant those at P-values < 0.05.

Results

Morphometrics

Overall, 733 wings were digitized and had the anatomic coordinates marked. Forty-one samples were considered outliers and excluded. The 692 samples were distributed in 43 different populations. The first two PCA axes explained 36% of the variation for the total sample. The first comparison was made between the sexes, with 298 females and 394 males. The first plane of the PCA (Additional file 1: Figure S1a) showed a higher concentration of females on the negative pole of component 2. We calculated the Mahalanobis distance between sexes (MD = 1.343), which was statistically significant (P < 0.0001). The cross-validation test wrongly classified 27–28% of the individuals according to sex (Additional file 1: Figure S1b). The box-plot (Additional file 1: Figure S1c) for the centroid size showed that the females were larger than males (P < 0.0001), as expected. Thus, we assumed that sexual dimorphism may have influenced differentiation and dealt with sexes separately. We excluded populations with low number of samples (n < 5). Therefore, the resulting dataset included 349 samples from 24 populations for males (Additional file 2: Table S1) and 284 specimens from 25 populations for females (Additional file 2: Table S2).

Figure 3 shows that insects were sorted according to the ecotope; peridomestic insects tended to be at the left pole of CV1 whereas sylvatic at the right pole of CV2, which exhibited a statistically significant MD (all > 1.21; P < 00001) irrespective of sex. Both sexes were larger in peridomestic insects (Fig. 3a–d), but domestic insects had smaller males (Fig. 3b) and larger females (Fig. 3d). However, domestic populations were represented by only 14 insects, divided into 5 populations.

When samples were grouped according to the municipality of collection (irrespective of collection site and ecotope), it was not possible to observe any grouping delimitation in the CVA plot in relation to sex (Additional file 3: Figure S2), even if the samples were sorted according to the ecotope within each municipality (data not shown, because the pattern remains the same).

In a CVA run within each municipality, almost all groups were delimited. The clear exception was for both sexes for populations from Currais Novos (Additional file 4: Figure S3). In Caicó-RN, females from the three locations of capture showed morphometric delimitation, whereas the males did not exhibit such structuring. The opposite was observed for the populations from Marcelino Vieira (Fig. 4).

For Emas-PB, all populations were delimited. However, for females, we did not have enough samples to compose the third population (EM94P). Populations from São José dos Espinhais-PB also showed some well-delimited groups for both sexes, even though there was some overlap (Fig. 5).

For Cajazeiras, clear delimitation was observed for males. For females of Cajazeiras, the peridomestic populations CZ18P and CZ19P were delimitated and there was an overlap for the remaining, that was composed of populations from distinct ecotopes. For Condado municipality, we only had a sufficient number for morphometric analysis for females but we observed that this peridomestic population (CD46D) was delimited in a group separated from others, which were isolated in distinct areas of the graph (Fig. 6).

Molecular variation in cytb gene

Sequences were generated from 221 individuals, distributed in 30 populations. The number of individuals sequenced per population varied from 3 to 10, but two populations were represented by only one sequence each. Overall, 57 segregating sites, 52 haplotypes (GenBank: MT720956-MT721007, Additional file 2: Table S4) and a haplotype diversity of 0.92 were observed. Nucleotide diversity was 0.00601. The Tajima’s D and Fu’s Fs tests indicated that, in general, DNA sequences are evolving randomly (“neutral”). The exceptions were for the wild populations of Caicó (CC51S; Tajima’s D), the peridomestic area of Currais Novos (CC69P and CN86P; for Fu’s Fs and Tajima’s D). The highest haplotypic diversity was observed for the populations CC51S (0.9556 ± 0.0594). The π value for SJ41S population was also the highest (0.003853 ± 0.002802), followed by MV29P (0.002486 ± 0.001997) and MV216S (0.001491 ± 0.001424), being below 0.001 for the remaining populations. The number of samples, haplotypes and remaining molecular statistics are provided in Additional file 2: Table S3. Additional file 2: Table S4 shows the estimates of evolutionary divergence between sequences based on K2P. All values were low (< 0.01), indicating that we were dealing with T. brasiliensis. The phylogenetic reconstruction by using unique haplotypes based on Bayesian inference revealed that posterior probabilities were low in general. For cases where these were higher than 80%, sequences had K2P lower than 0.009, confirming we were dealing with haplotypes with low variation. The molecular evolution model was HKY + G based on BIC (Additional file 5: Figure S4).

The ΦST tree is illustrated in Fig. 7. The values of ΦST are given in Additional file 2: Table S5. The tree built with genotypic data showed the geographical force of the distribution of genetic variation. For example, the majority of Currais Novos (CN#) populations are associated with the same branch (Fig. 7a). Morphometric results exhibited geographical groupings as for males of Marcelino Vieira (MV#) (Fig. 7b), but also ectopic, indicated by red rectangles. Most of the morphometric population comparisons were statistically significant (Additional file 2: Table S1 for males and Additional file 2: Table S2 for females). We highlight the discrepancies of the trees based on genetic and morphometric data: the tree based on genetic data exhibited more consistent geographical groupings whereas the trees based on morphometrics exhibited groupings for both scales (geographical and ecotypic) (Fig 7b, c).

Trees derived from pairwise molecular differentiation coefficient (a) and morphometric analyses Mahalanobis distances for males (b) and females (c) of Triatoma brasiliensis populations. Details for each population of T. brasiliensis are provided in Additional file 2. Black rectangles refer to geographical related populations and the red rectangles indicate populations ecotypic-related

Analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) (Table 1) demonstrated that when populations are grouped according to the municipality, 18% of the variation is among municipalities and 36% among populations within municipalities. However, variation among groups of municipalities was significant (P = 0.001). Following the hypothesis that the genetic structure may be driven by ecotypic force (predominant migration between the same ecotopes), a second test was performed by nesting groups of populations defined by their ecotopes within each municipality. For this kind of nesting, the percentage of variation between groups was even lower (10%) and the variation within groups was higher (41%). For both kinds of nesting populations, most of the variation was observed within populations (46–49%).

Correlation between matrices

All Mantel tests comparing the matrices showed a significant correlation (P < 0.05) but in general, correlations were low. The highest correlation occurred between the MD between males and females (R2 = 0.74), as expected. The remaining correlations exhibited low values, such as between the ΦST/MD and the geographical distance (R2 < 0.36). For both sexes, the correlations between MD and ΦST were also low (R2 = 0.13–0.15).

Discussion

The differences between the distributional patterns of morphometric and genetic variation have been extensively explored for insect vectors [51,52,53]. For the T. brasiliensis complex, interspecific molecular and morphometric variations have also been studied [22]. Population variations based on morphology can be influenced by ecotypic and environmental variations, but they are also influenced by the individual’s genotypic information [54]. Therefore, geometric morphometrics approaches are also used to recognize microevolutionary processes [32]. The first study in this sense for T. brasiliensis used classical morphometry [55]. The second study was conducted at a microgeographical scale perspective and had a restricted sampling number (n = 97), but it was a pioneer study by using geometric morphometrics for assessing the variation among ecotypic populations [26]. Our study brings up the first effort by using a large sampling of T. brasiliensis (initial n of 733 insects) on a wider geographical scale ranging from 95 km (North-South) to 240 km (East-West). Additionally, the morphometric information is here associated with genotypic variations. Some authors [56, 57] concluded that morphometrics combined with genetic information can improve the understanding of the re-infestation process and contribute to vector control strategies when the approach is used in the microgeographical scale. In this study, molecular variation was used as a tool for monitoring and control, as the chosen marker (variation in the mitochondrial gene cytb) does not suffer the influence of the environmental variation [58]. Thus, this study is also a pioneer in contrasting robustally the ecotypic effect on morphometric variation for Brazilian Chagas disease vectors.

Considering all the samples grouped according to the ecotopes and for each sex, we observed a relative ecotypic grouping in the PCA. Similarly, in Ceará, Batista et al. [26] found significant differences between T. brasiliensis collected in different ecotopes. The peridomestic individuals were significantly larger than the sylvatic individuals. Costa et al. [13] mentioned that wild populations of T. brasiliensis are usually found hungry in the field, which may explain the difference in size. We suggest that domestic insects did not have numbers enough for inferring the size. Geometric morphometrics effectively minimizes the size factor, but it does not eliminate it totally [32]. The ecotopes seem to influence the morphometric variation, which may represent the bias of geometric morphometry for inferences on genetic structuring. However, as discussed below, some peridomestic populations were more morphometrically associated with some sylvatic bug populations than other peridomestic populations, when the observation is carried out on a microgeographical scale.

In the dendrograms derived from the Mahalanobis distances (MD), it was possible to observe that some groups were formed by nearby populations, indicating geographical structure. The District of Patos is composed of the municipalities of Emas, São José de Espinharas, Santa Teresinha, Condado, all in the State of Paraíba with related bug populations. However, the Mantel test showed a weak correlation between the morphometric and geographical distance matrices, which may indicate that forces, other than geographical, maybe also driving the morphometric variation. For T. infestans in Argentina, the resolution of geometric morphometry to detect differences in macrogeographical scales was more evident in comparisons of individuals separated by municipality [56]. However, the authors did not apply any matrix correlation tests (Mantel tests). Additionally, these authors did not include insects from wild populations.

Principal components analysis (PCA) is the most popular method to characterize shape variation [33]. However, when the data involve subgroups, the PCA should be used as a method for ordering large groups, with the canonical variates analysis (CVA) being the most appropriate for the subgroups. The factorial maps constructed with the CVAs in populations defined by collection point within each municipality (on a microgeographical scale) were the only maps to delimit the populations. Pilot tests with PCAs could not delimit populations even for macroeographical scales.

For both sexes, no structure was observed for the populations from Currais Novos; and for Caicó there was grouping delimitation only for females in CVA graphs. The lack of correlation between the CVA graphs in regard to sexes for Caicó may indicate a different migration pattern. However, for overall results, the Mantel test showed 73% correlation between males and females for MDs. For T. dimidiata (Latreille, 1811), Stevens et al. [59] found no significant differences in gene flow between the sexes using microsatellite markers. For T. juazeirensis, a member of the T. brasiliensis complex, Carbajal de la Fuente et al. [60] found more males than females in light traps, which capture flying insects (dispersants). Lilioso et al. [61] captured T. brasiliensis via active search, and they found more than twice males than females in sylvatic environments. This may indicate the existence of distinct patterns of migration between sexes.

We found low variation among T. brasiliensis sequences (all K2P were < 0.01). This value is expected intraspecifically since the values reported between the subspecies T. b. brasiliensis and T. b. macromelasoma were higher (K2P = 0.03) [17]. Therefore, we assumed we were dealing with closely related entities. For mosquitoes, Lorenz et al. [62] presented interesting clues about selective patterns observed by molecular markers, which were corroborated by morphometric markers. However, the neutrality tests here applied pointed to a random (“neutral”) evolution for our sampling. In other words, we did not evidence directional or balancing selection, as well as expansion or demographic contraction. Therefore, we could not provide inferences on molecular and morphometric results in this sense. Indeed, the neutral evolution for the molecular marker chosen is in agreement with the results of Almeida et al. [25] which used the same gene fragment in Caicó-RN [5] and also in São José da Lagoa Tapada-PB [5].

The hierarchical molecular variance analysis (AMOVA) was conducted to evaluate the role of geographical and ecotypic forces in the genetic structure of T. brasiliensis. In this case, it is known that the ecotope does not influence the genotype, but for some triatomine vectors, gene flow occurs predominantly between ecotopes, as observed for T. infestans in the Andean valleys [63]. Here, neither the geographical force nor the ecotypic one explained the distribution of molecular variation, based on the observation that the greater percentage of variation was detected within groups and within geographical and ecotypic populations. Additionally, Mantel tests showed a low correlation between geographical and genetic variation. These results corroborate Almeida et al. [5, 25], although these authors have noticed some degree of influence of ecotypic force. However, at this point, the morphometric and molecular results were in agreement. What is noteworthy, is that the molecular and morphometric markers were in agreement to indicate an association between a sylvatic and a peridomestic population of Marcelino Vieira (MV188P-MV216S; Figs. 4, 6a). It is important to note that the population MV188P was collected at the site where a Chagas disease outbreak occurred [64].

Both molecular and morphometric markers can be applied to understand macroevolutionary and microevolutionary processes in vector insects [65]. Concerning microevolutionary processes, in general, the dendrogram constructed with the ΦST matrices revealed that the geographical forces play a role in the distribution of genetic variation. However, most populations of Currais Novos were in the same cluster for morphometrics of males from Marcelino Veira. This was observed for some populations of Cajazeiras and Emas, although AMOVA has not shown statistical significance for geographical structuring. On the other hand, this corroborates the results of morphometry, in which Mantel tests did not evidence correlation between matrices of geographical and Mahalanobis distances.

The comparison of the results of the molecular and morphometric tools showed low conformity by Mantel tests. But in all dendrograms, the populations of Cajazeiras and Currais Novos trend to be grouped in the same branch. This indicates that in some cases the markers are in agreement. This conformity has already been tested by other authors and for other species, such as T. dimidiata (Latreille, 1811) in the Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico [66] and T. infestans in Argentina [56]. For T. dimidiata the authors did not find remarkable conformity between markers [66], which may be explained by the distinct resolution of molecular and morphometric markers [67].

The strategy of observing variations within a smaller geographical scale aimed to seek clues about the processes of (peri) household infestation. To our knowledge, this is the first attempt in the literature to test geometric morphometrics for this purpose focusing on vectors of Chagas disease in Brazil. Schachter-Broide et al. [68] applied the approach to this inference for T. infestans in Argentina, concluding that geometric morphometrics represents a useful tool. However, the populations analyzed by these authors all came from artificial ecotopes. We must emphasize that our results suggest that the ecotope seems to have an important effect on phenotypic variation. Therefore, the morphometric associations between populations of different ecotopes on the microgeographical scale can present important clues to detect infestation processes when analyzed within the same municipality. In this sense, geometric morphometrics was more sensitive to delimit populations on a microgeographical scale than on a macrogeographical scale, which was evidenced in the factorial maps. For example, in the maps illustrating the analysis of canonical variables for both males and females, the peridomestic populations of Cajazeiras and São José de Espinharas showed associations with sylvatic populations. These findings corroborate the idea that this tool can be used to detect infestation foci [32]. However, caution is needed for this conclusion. We recommend the combination of morphometry with molecular markers of higher resolution, such as single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) [69] to validate morphometric results.

The genome of T. brasiliensis may carry information that allows equal morphological plasticity throughout the entire collection range which prevents structuring on the macrogeographical scale. However, demographic events, such as bottlenecks or founder effects, might be acting to maintain homogeneity in groups of insects collected at the same point, as recently observed for Brazilian populations of T. sordida [70]. Retention of the ancestral character and convergences in sampled populations can also help explain the results of morphological plasticity. The retention was already verified by molecular tools: the ancestral haplotype of cytb is the most frequent in the entire collection range, and this phenomenon is well known for T. brasilensis [5, 17, 25]. Almeida et al. [25] could not delimit populations using the cytb gene on a microgeographical scale. The power demonstrated by geometric morphometrics to delimit populations on a microgeographical scale indicates that this tool has a higher resolution in revealing population structure than the molecular marker used here.

The ecologic niche model was used for the first evaluation of the distributional potential of members of T. brasiliensis in the present and also for future climate scenarios - global warming. Model projections indicated the potential for expansions of T. brasiliensis for 2050, highlighting the need for constant monitoring T. brasiliensis distribution [71].

Conclusions

The most remarkable result obtained here was the resolution in the population delimitation on a microgeographical scale for geometric morphometrics, which was sometimes in agreement with the results of molecular variation. At this scale, populations from distinct ecotopes appeared to be more associated in some cases, which questions the role of the ecotope on the distribution of morphometric variation. This indicates that geometric morphometrics can be used to assess population structure, microevolutionary processes and to look for foci of reinfestation. The combination of molecular and morphometric markers have the potential to be used in decision-making for more rational, targeted and resource-saving control measures (as for spraying domiciles with insecticides). Additionally, the geometric morphometrics based on the venation of the wings of triatomines is a low-cost and quick-to-perform technique. Therefore, the results presented here indicate that there is potential applicability of this technique in vector control measures in the near future.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its additional files. The newly generated sequences were deposited in the GenBank database under the accession numbers MT720956-MT721007.

Abbreviations

- MD:

-

Mahalanobis distance

- CVA:

-

canonical variate analysis

- AMOVA:

-

analysis of molecular variance

- PCA:

-

principal components analysis

- RN:

-

Rio Grande do Norte State, Brazil

- PB:

-

Paraíba State, Brazil

- CC:

-

Caicó City, Brazil

- CN:

-

Currais Novos City, Brazil

- MV:

-

Marcelino Vieira City, Brazil

- CD:

-

Condado City, Brazil

- CZ:

-

Cajazeiras City, Brazil

- ST:

-

Santa Terezinha City, Brazil

- SJ:

-

São José dos Espinharas City, Brazil

- SM:

-

São Mamede City, Brazil

- EM:

-

Emas City, Brazil

References

WHO. Integrating neglected tropical diseases. Fact Sheet March 2017. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017.

Galvão C, Jurberg J. Introdução. Vetores da Doença Chagas no Bras. Curitiba (Brazil): Sociedade Brasileira de Zoologia; 2014. p. 5–9.

Sarquis O, Borges-Pereira J, Mac Cord JR, Gomes TF, Cabello PH, Lima MM. Epidemiology of chagas disease in Jaguaruana, Ceará, Brazil I Presence of triatomines and index of Trypanosoma cruzi infection in four localities of a rural area. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2004;99:263–70.

Bezerra CM, Barbosa SE, De Souza RDCM, Barezani CP, Gürtler RE, Ramos AN, et al. Triatoma brasiliensis Neiva, 1911: food sources and diversity of Trypanosoma cruzi in wild and artificial environments of the semiarid region of Ceará, northeastern Brazil. Parasit Vectors. 2018;11:642.

Almeida CE, Faucher L, Lavina M, Costa J, Harry M. Molecular individual-based approach on Triatoma brasiliensis: inferences on triatomine foci, Trypanosoma cruzi natural infection prevalence, parasite diversity and feeding sources. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10:e0004447.

Costa J, Almeida CE, Dotson EM, Lins A, Vinhaes M, Silveira AC, et al. The epidemiologic importance of Triatoma brasiliensis as a Chagas disease vector in Brazil: a revision of domiciliary captures during 1993–1999. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2003;98:443–9.

Dale C, Almeida CE, Mendonça VJ, Oliveira J, da Rosa JA, Galvão C, et al. An updated and illustrated dichotomous key for the Chagas disease vectors of Triatoma brasiliensis species complex and their epidemiologic importance. ZooKeys. 2018;805:33–43.

Lent H, Wygodzinsky PW. Revision of the triatominae (Hemiptera: Ruduviidae), and their significance as vectors of Chagas’ disease. Bull Am Museum Nat Hist. 1979;163:123–520.

Costa J, Almeida CE, Dujardin JP, Beard CB. Crossing experiments detect genetic incompatibility among populations of Triatoma brasiliensis Neiva, 1911 (Heteroptera, Reduviidae, Triatominae). Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2003;98:637–9.

Costa J, Bargues MD, Neiva VL, Lawrence GG, Gumiel M, Oliveira G, et al. Phenotypic variability confirmed by nuclear ribosomal DNA suggests a possible natural hybrid zone of Triatoma brasiliensis species complex. Infect Genet Evol. 2016;37:77–87.

Costa J, Cordeiro Correia N, Neiva VL, Gonçalves TCM, Felix M. Revalidation and redescription of Triatoma brasiliensis macromelasoma Galvão, 1956 and an identification key for the Triatoma brasiliensis complex (Hemiptera: Reduviidae: Triatominae). Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2013;108:785–9.

Costa J, Freitas-Sibajev MGR, Marchon-Silva V, Pires MQ, Pacheco RS. Isoenzymes detect variation in populations of Triatoma brasiliensis (Hemiptera: Reduviidae: Triatominae). Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1997;92:459–64.

Costa J, Peterson AT, Ben BC. Ecologic niche modeling and differentiation of populations of Triatoma brasiliensis neiva, 1911, the most important Chagas’ disease vector in Northeastern Brazil (hemiptera, reduviidae, triatominae). Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1911;2002(67):516–20.

Schofield CJ, Galvão C. Classification, evolution, and species groups within the Triatominae. Acta Trop. 2009;110:88–100.

Costa J, Felix M. Triatoma juazeirensis sp. nov. from the state of Bahia, northeastern Brazil (Hemiptera: Reduviidae: Triatominae). Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2007;102:87–90.

Costa J, Argolo AM, Felix M. Redescription of Triatoma melanica Neiva & Lent, 1941, new status (Hemiptera: Reduviidae: Triatominae). Zootaxa. 2006;1385:47–52.

Monteiro FA, Donnelly MJ, Beard CB, Costa J. Nested clade and phylogeographic analyses of the Chagas disease vector Triatoma brasiliensis in Northeast Brazil. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2004;32:46–56.

Mendonça VJ, Da Silva MTA, De Araújo RF, Martins J, Bacci M, Almeida CE, et al. Phylogeny of Triatoma sherlocki (Hemiptera: Reduviidae:Triatominae) inferred from two mitochondrial genes suggests its location within the Triatoma brasiliensis complex. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;81:858–64.

Mendonça VJ, Alevi KCC, Medeiros LMO, Nascimento JD, de Azeredo-Oliveira MTV, da Rosa JA. Cytogenetic and morphologic approaches of hybrids from experimental crosses between Triatoma lenti Sherlock & Serafim, 1967 and T. sherlocki Papa et al., 2002 (Hemiptera: Reduviidae). Infect Genet Evol. 2014;26:123–31.

Correia N, Almeida CE, Lima-Neiva V, Gumiel M, Dornak LL, Lima MM, et al. Cross-mating experiments detect reproductive compatibility between Triatoma sherlocki and other members of the Triatoma brasiliensis species complex. Acta Trop. 2013;128:162–7.

Alevi KCC, Mendonça PP, Pereira NP, Guerra AL, Facina CH, da Rosa JA, et al. Distribution of constitutive heterochromatin in two species of triatomines: Triatoma lenti Sherlock and Serafim (1967) and Triatoma sherlocki Papa, Jurberg, Carcavallo, Cerqueira & Barata (2002). Infect Genet Evol. 2013;13:301–3.

Oliveira J, Marcet PL, Takiya DM, Mendonça VJ, Belintani T, Bargues MD, et al. Combined phylogenetic and morphometric information to delimit and unify the Triatoma brasiliensis species complex and the Brasiliensis subcomplex. Acta Trop. 2017;170:140–8.

Mendonca VJ, Alevi KCC, Pinotti H, Gurgel-Goncalves R, Pita S, Guerra AL, et al. Revalidation of Triatoma bahiensis Sherlock & Serafim, 1967 (Hemiptera: Reduviidae) and phylogeny of the T. brasiliensis species complex. Zootaxa. 2016;4107:239–54.

Mendonça VJ, Alevi KCC, Medeiros LMO, Nascimento JD, Azeredo-Oliveira MTV, Rosa JA, et al. Distribution of constitutive heterochromatin between Triatoma lenti (Sherlock & Serafim, 1967) and T. sherlocki (Papa et al., 2002) (Hemiptera: Reduviidae). Infect Genet Evol. 2002;2014(26):123–31.

Almeida CE, Pacheco RS, Haag K, Dupas S, Dotson EM, Costa J. Inferring from the Cyt B gene the Triatoma brasiliensis Neiva, 1911 (Hemiptera: Reduviidae: Triatominae) genetic structure and domiciliary infestation in the State of Paraíba, Brazil. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;78:791–802.

Batista VSP, Fernandes FA, Cordeiro-Estrela P, Sarquis O, Lima MM. Ecotope effect in Triatoma brasiliensis (hemiptera: Reduviidae) suggests phenotypic plasticity rather than adaptation. Med Vet Entomol. 2013;27:247–54.

Almeida CE, Oliveira HL, Correia N, Dornak LL, Gumiel M, Neiva VL, et al. Dispersion capacity of Triatoma sherlocki, Triatoma juazeirensis and laboratory-bred hybrids. Acta Trop. 2012;122:71–9.

Leal IR, da Silva JMC, Tabarelli M, Lacher TE Jr, Lacher TE. Changing the course of biodiversity conservation in the Caatinga of northeastern Brazil. Conserv Biol. 2005;19:701–6.

Rohlf RJ. TPSDIG, version 2.12. New York: Department of Ecology and Evolution, Stony Brook University; 2008.

Rohlf FJ. Morphometrics. Annu Rev Ecol Syst. 1990;21:229–316.

Zelditch ML, Swiderski DL, Sheets HD, Fink WL. Geometric morphometrics for biologists: a primer. London: Academic Press; 2004.

Dujardin JP. Morphometrics applied to medical entomology. Infect Genet Evol. 2008;8:875–90.

Klingenberg CP. MorphoJ: an integrated software package for geometric morphometrics. Mol Ecol Resour. 2011;11:353–7.

Mardia KV, Dryden IL. The statistical analysis of shape data. Biometrika. 1989;76:271–81.

Kent JT, Mardia KV. Consistency of procrustes estimators. J R Stat Soc Ser B Stat Methodol. 1997;59:281–90.

Lele RS, Richtsmeier JT. An invariant approach to statistical analysis of shapes. Philadelphia: CRC Press; 2001. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781420036176.

Lyman DF, Monteiro FA, Escalante AA, Cordon-Rosales C, Wesson DM, Dujardin JP, et al. Mitochondrial DNA sequence variation among triatomine vectors of Chagas’ disease. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;60:377–86.

Monteiro FA, Barrett TV, Fitzpatrick S, Cordon-Rosales C, Feliciangeli D, Beard CB. Molecular phylogeography of the Amazonian Chagas disease vectors Rhodnius prolixus and R robustus. Mol Ecol. 2003;12:997–1006.

Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: Improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–80.

Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–10.

Drummond AJ, Suchard MA, Xie D, Rambaut A. Bayesian phylogenetics with BEAUti and the BEAST 17. Mol Biol Evol. 2012;29:1969–73.

Rambaut A, Drummond AJ, Xie D, Baele G, Suchard MA. Software for systematics and evolution posterior summarization in Bayesian phylogenetics using Tracer 1.7. Syst Biol. 2018;67:901–4.

Nylander JAA. MrModeltest v2. Uppsala: Uppsala University, Evolutionary Biology Centre; 2004.

Kimura M. A simple method for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J Mol Evol. 1980;16:111–20.

Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across computing platforms. Mol Biol Evol. 2018;35:1547–9.

Tajima F. Statistical method for testing the neutral mutation hypothesis by DNA polymorphism. Genetics. 1989;123:585–95.

Fu YX. Statistical tests of neutrality of mutations against population growth, hitchhiking and background selection. Genetics. 1997;147:915–25.

Excoffier L, Smouse PE, Quattro JM. Analysis of molecular variance inferred from metric distances among DNA haplotypes: application to human mitochondrial DNA restriction data. Genetics. 1992;131:479–91.

Rozas J, Ferrer-Mata A, Sanchez-DelBarrio JC, Guirao-Rico S, Librado P, Ramos-Onsins SE, et al. DnaSP 6: DNA sequence polymorphism analysis of large data sets. Mol Biol Evol. 2017;34:3299–302.

Excoffier L, Lischer HEL. Arlequin suite ver 3.5: a new series of programs to perform population genetics analyses under Linux and Windows. Mol Ecol Resour. 2010;10:564–7.

Sontigun N, Samerjai C, Sukontason K, Wannasan A, Amendt J, Tomberlin JK, et al. Wing morphometric analysis of forensically important flesh flies (Diptera: Sarcophagidae) in Thailand. Acta Trop. 2019;190:312–9.

Nattero J, Cecere MC, Gürtler RE. Temporal variations of fluctuating asymmetry in wing size and shape of Triatoma infestans populations from northwest Argentina. Infect Genet Evol. 2017;56:133–42.

Costa J, Peterson AT, Dujardin JP. Morphological evidence suggests homoploid hybridization as a possible mode of speciation in the Triatominae (Hemiptera, Heteroptera, Reduviidae). Infect Genet Evol. 2009;9:263–70.

Dujardin JP, Kaba D, Henry AB. The exchangeability of shape. BMC Res Notes. 2010;3:266.

Borges ÉC, Dujardin JP, Schofield CJ, Romanha AJ, Diotaiuti L. Dynamics between sylvatic, peridomestic and domestic populations of Triatoma brasiliensis (Hemiptera: Reduviidae) in Ceará State, northeastern Brazil. Acta Trop. 2005;93:119–26.

Gaspe MS, Provecho YM, Piccinali RV, Gürtler RE. Where do these bugs come from? Phenotypic structure of Triatoma infestans populations after control interventions in the Argentine Chaco. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2015;110:310–8.

Gaspe MS, Gurevitz JM, Gürtler RE, Dujardin JP. Origins of house reinfestation with Triatoma infestans after insecticide spraying in the Argentine Chaco using wing geometric morphometry. Infect Genet Evol. 2013;17:93–100.

Monteiro FA, Weirauch C, Felix M, Lazoski C, Abad-Franch F. Evolution, systematics, and biogeography of the triatominae, vectors of Chagas disease. Adv Parasitol. 2018;99:265–344.

Stevens L, Monroy MC, Rodas AG, Hicks RM, Lucero DE, Lyons LA, et al. Migration and gene flow among domestic populations of the chagas insect vector Triatoma dimidiata (hemiptera: Reduviidae) detected by microsatellite loci. J Med Entomol. 2015;52:419–28.

Carbajal Fuente AL, Minoli SA, Lopes CM, Noireau F, Lazzari CR, Lorenzo MG. Flight dispersal of the Chagas disease vectors Triatoma brasiliensis and Triatoma pseudomaculata in northeastern Brazil. Acta Trop. 2007;101:115–9.

Lilioso M, Folly-Ramos E, Rocha FL, Rabinovich J, Capdevielle-Dulac C, Harry M, et al. High Triatoma brasiliensis densities and Trypanosoma cruzi prevalence in domestic and peridomestic habitats in the State of Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil: the source for Chagas disease outbreaks? Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2017;96:1456–9.

Lorenz C, Almeida F, Almeida-Lopes F, Louise C, Pereira SN, Petersen V, et al. Geometric morphometrics in mosquitoes: what has been measured? Infect Genet Evol. 2017;54:205–15.

Piccinali RV, Marcet PL, Ceballos LA, Kitron U, Gürtler RE, Dotson EM. Genetic variability, phylogenetic relationships and gene flow in Triatoma infestans dark morphs from the Argentinean Chaco. Infect Genet Evol. 2011;11:895–903.

Vargas A, Malta JMAS, Costa VM, Cláudio LDG, Alves RV, Cordeiro GS, et al. Investigação de surto de doença de Chagas aguda na região extra-amazônica, Rio Grande do Norte, Brasil, 2016. Cad Saude Publica. 2018;34:e00006517.

Lorenz C, Marques TC, Sallum MAM, Suesdek L. Altitudinal population structure and microevolution of the malaria vector Anopheles cruzii (Diptera: Culicidae). Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:581.

Dumonteil E, Tripet FFF, Ramirez-Sierra MJ, Payet V, Lanzaro G, Menu FFF. Assessment of Triatoma dimidiata dispersal in the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico by morphometry and microsatellite markers. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;76:930–7.

Piccinali RV, Gurtler RE. Fine-scale genetic structure of Triatoma infestans in the Argentine Chaco. Infect Genet Evol. 2015;34:143–52.

Schachter-broide J, Dujardin JP, Kitron U, Gürtler RE. Spatial Structuring of Triatoma infestans (Hemiptera, Reduviidae) populations from Northwestern Argentina using wing geometric morphometry. J Med Entomol. 2004;41:643–9.

Campos M, Conn JE, Alonso DP, Vinetz JM, Emerson KJ, Ribolla PEM. Microgeographical structure in the major Neotropical malaria vector Anopheles darlingi using microsatellites and SNP markers. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10:76.

Madeira FF, Dos Reis YV, De Freitas Bittinelli I, Delgado LMG, De Oliveira J, Mendonça VJ, et al. Genetic structure of brazilian populations of Triatoma sordida (stal, 1859) (Hemiptera, Triatominae) by means of chromosomal markers. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2019;100:907–10.

Costa J, Dornak LL, Almeida CE, Peterson AT. Distributional potential of the Triatoma brasiliensis species complex at present and under scenarios of future climate conditions. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:238.

Acknowledgements

We thank the technicians of Funasa for essential help in the field, especially to Dr Lúcia Maria Abrantes Aguiar (Secretaria de Estado da Saúde Pública do Rio Grande do Norte, Natal, Brasil) for kindly arranging all the field work. We also thank the Pos Graduating Program, especially to Professors Dr Silmara Marques Allegretti and Fernanda J Cabral for all dedication. We are greatful to do Professor Dr. Jean-Pierre Dujardin for all suggestions.

Funding

Financial support was provided by The São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP process numbers 2016/08176-9, 2017/15210-1, 2017/09088-9, 2017/21359-8, 2018/04205-0, 2018/04594-6, 2017/19420-0), the Brazilian Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq Process number 434260/2018-5) and the agreement UNICAMP-CNRS (FAPESP process numbers 17/50329-0). ALCF is a member of the CONICET Researcher’s Career. CEA and JC are CNPq Research Productivity Granted - PQ-2 (306357/2019-4 and 303363/2017-7). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CEA designed the study. EHK and FHMF worked on formal analysis. CEA and JC were responsible for funding acquisition. CEA, ML and EFR collected the insects. EHK, ML, CVB and EFR performed the laboratory investigations. EHK, MCV, FHMF, ML, ALCF, DPS and CVB conducted the data analysis. EHK, FHMF, ML and CEA prepared the original draft. EHK, FHMF, ALCF, ML, DPS, PJT, VNS, EFR, JC and CEA revised and edited the final version. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Brazilian Environmental Agency: license codes SISBIO IBAMA 58373, 32579-1; SISGEN AF53F3B. We obtained permission from house owners/residents to search for insects in all properties and we visited four houses in each site.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Figure S1

. a PCA for the morphometric variation of all T. brasiliensis. Red dots represent females and blue dots represent males. b The canonical variable using the discriminating function of the variation between the sexes. c Boxplots representing variations in the size of the wing centroid.

Additional file 2: Table S1.

Statistics for the Mahalanobis distance of males. Table S2. Statistics for the Mahalanobis distance of females. Table S3. Summary statistics of genetic diversity. Table S4. Estimates of evolutionary divergence between cyt B fragments (447bp). Table S5. ΦST pairwise population comparisons for all populations.

Additional file 3: Figure S2.

Graphics of Canonical Variance for males (a) and females (b) T. brasiliensis populations grouped by municipality. See Fig. 1 for the acronyms of municipalities. Abbreviations: CC, Caicó-RN; CD, Condado-PB; CN, Currais Novos-RN; CZ, Cajazeiras-PB; EM, Emas-PB; MV, Marcelino Vieira-RN; SJ, São José de Espinharas-PB; ST, Santa Teresinha-PB.

Additional file 4: Figure S3.

Left: The locations where T. brasiliensis populations were collected in CurraisNovos, State of Rio Grande do Norte. Right: Canonical variate analysis (CVA) based on CVA1 and CVA2 for both sexes.

Additional file 5: Figure S4.

Bayesian phylogenetic tree based on the cytb gene (447 bp) for T. brasiliensis using the molecular evolution model TN93 + I. Posterior probabilities are indicated at the nodes. Outgroup: T. petrocchiae (GenBank: MN177967).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Kamimura, E.H., Viana, M.C., Lilioso, M. et al. Drivers of molecular and morphometric variation in Triatoma brasiliensis (Hemiptera: Triatominae): the resolution of geometric morphometrics for populational structuring on a microgeographical scale. Parasites Vectors 13, 455 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-020-04340-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-020-04340-7