Abstract

Background

The transmission of mosquito-borne pathogens is strongly influenced by the contact rates between mosquitoes and susceptible hosts. The biting rates of mosquitoes depend on different factors including the mosquito species and host-related traits (i.e. odour, heat and behaviour). However, host characteristics potentially affecting intraspecific differences in the biting rate of mosquitoes are poorly known. Here, we assessed the impact of three host-related traits on the biting rate of two mosquito species with different feeding preferences: the ornithophilic Culex pipiens and the mammophilic Ochlerotatus (Aedes) caspius. Seventy-two jackdaws Corvus monedula and 101 house sparrows Passer domesticus were individually exposed to mosquito bites to test the effect of host sex, body mass and infection status by the avian malaria parasite Plasmodium on biting rates.

Results

Ochlerotatus caspius showed significantly higher biting rates than Cx. pipiens on jackdaws, but non-significant differences were found on house sparrows. In addition, more Oc. caspius fed on female than on male jackdaws, while no differences were found for Cx. pipiens. The biting rate of mosquitoes on house sparrows increased through the year. The bird infection status and body mass of both avian hosts were not related to the biting rate of both mosquito species.

Conclusions

Host sex was the only host-related trait potentially affecting the biting rate of mosquitoes, although its effect may differ between mosquito and host species.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The blood-feeding behaviour of mosquitoes is a complex phenomenon that involves different steps. The initial seeking and location of hosts depends on the integration of chemical (e.g. CO2, odours) and visual cues (e.g. host size and plumage/pelage coloration) emitted by the host [1, 2]. In close proximity between mosquitoes and their hosts, odour, heat and host defensive behaviour may affect the final host choice and blood-feeding success of mosquitoes [3].

Under natural conditions, mosquitoes show different innate feeding preferences, with some species feeding mostly on mammals (mammophilic species, and some of them can be characterized as anthropophilic), while others preferring to bite birds (ornithophilic species), or even amphibians or reptiles, yet other species show a more opportunistic behaviour [4,5,6,7,8]. In addition to this broad tendency for particular host classes, mosquitoes bite certain host species at higher rates than those expected from their abundance [9,10,11]. For instance, Kilpatrick et al. [9] showed that American robins (Turdus migratorius) were more intensely bitten by Culex pipiens mosquitoes than European starlings (Sturnus vulgaris) in North America. Similarly, in Europe, the feeding preference of Cx. pipiens for blackbirds (Turdus merula) was higher than for European starlings [12]. Within host species, some individuals may receive most mosquito bites and, as a result, they may play a role as superspreaders when infected with vector-borne pathogens [13].

This heterogeneity in vector attraction and host use by mosquitoes could have important impacts on the dynamics of transmission of parasites causing human and animal diseases [14]. Among others, these factors may determine the transmission success of parasites such as protozoans (e.g. Plasmodium spp.) and filarial worms (e.g. Dirofilaria spp.) [2, 15].

Different non-mutually exclusive mechanisms may determine that an individual host receives more mosquito bites, such as, for instance, the use of habitats with higher abundance of mosquitoes, a higher emission of attractive cues, or a less intense or effective anti-mosquito behaviour than other conspecifics [7]. In addition, larger hosts (i.e. with a larger body mass, as a correlate of body size), may receive more bites by mosquitoes [16] probably due to the higher amounts of cues (e.g. CO2) released by larger individuals [17]. Different studies at the interspecific level have reported a positive relationship between host body mass and the feeding rate of different blood-sucking insects [18, 19]. However, very few studies have experimentally tested the relationship between species variation in body mass and the feeding rate of mosquitoes [20]. In addition, sex-specific morphological, physiological and/or behavioural characteristics could produce differences in the attraction of insect vectors [21]. These differences in vector attraction between host sexes have been argued as a potential explanation for the usually higher prevalence of blood parasites found in male than in female birds [22,23,24]. However, to the best of our knowledge, only Burkett-Cadena et al. [25] evaluated the effect of bird sex on the variation in mosquito biting preferences. By analysing the blood-meal origin of mosquitoes, authors found that blood meals were biased towards male birds, but only in mammophilic mosquitoes. However, the reasons of these differences remain unclear. Patterns found by Burkett-Cadena et al. [25] could be the result of a differential susceptibility, attraction and/or exposure of bird sexes to mosquito attacks or simply an unbalanced bird sex-ratio in the areas where mosquitoes were captured. Finally, the host infection status by vector-borne parasites may also influence the mosquito biting patterns, potentially determining the pathogen transmission success [26, 27]. For example, humans infected with Plasmodium vivax were more attractive to mosquito vectors [28]. However, studies with avian Plasmodium are less conclusive, because Cx. pipiens, the main vector of avian Plasmodium, was reported to preferentially bite chronically infected birds over uninfected individuals according to Cornet et al. [26, 27], but other studies have reported the opposite pattern [29] or even the absence of significant differences between infected and uninfected birds [30].

In this study, we experimentally assessed the impact of three host-related traits (body mass, sex and infection status by avian Plasmodium) on mosquito feeding patterns, while removing host anti-mosquito behaviour. We performed this study using two mosquito species with different feeding preferences: the ornitophilic Cx. pipiens and the mammophilic Ochlerotatus (Aedes) caspius [8, 31, 32]. We used two bird species as host models, the jackdaw (Corvus monedula) and the house sparrow (Passer domesticus). Both bird species are common hosts of avian malaria parasites [33, 34]. Based on previous evidence [19, 25,26,27], we predicted (i) a higher biting rate on birds in the ornithophilic Cx. pipiens than in the mammophilic Oc. caspius; (ii) a higher mosquito biting rate on heavier individuals; (iii) a higher biting rate on male birds over females, especially for Oc. caspius; and (iv) a higher biting rate on Plasmodium-infected birds than on uninfected individuals.

Methods

Mosquito collection and rearing

Culex pipiens and Oc. caspius larvae were collected from March to August in 2014 and 2016 in the natural reserve ‘La Cañada de los Pájaros’ (36°57′N, 6°14′W; Seville Province, Spain) and in marshlands of Huelva Province (37°17′N, 6°53′W), respectively. Larvae were transferred to the laboratory and kept in plastic trays with fresh or brackish water, respectively, and fed ad libitum with Mikrozell 20 ml/22 g (Dohse Aquaristik GmbH & Co. KG, Gelsdorf, Germany). Larvae and adult mosquitoes were maintained under standard conditions (28 ± 1 °C, 65–70% RH and 12:12 light:dark photocycle). Adult mosquitoes were anesthetized with ether and their sex and species identified based on morphology, on chilled Petri dishes using a stereomicroscope (Nikon SMZ645, Tokyo, Japan) following Schaffner et al. [35]. After identification, adult females were placed in insect cages (BugDorm-43030F, 32.5 × 32.5 × 32.5 cm; MegaView Science Co, Taichung, Taiwan) and fed ad libitum on 1% sugar solution. Twenty-four hours prior to each experiment, female mosquitoes were deprived from sugar solution. Laboratory maintained colonies of mosquitoes were not used to minimize the effects of artificial selection of mosquitoes with particular biting preferences [36, 37].

Bird sampling and experimental procedure

The jackdaw is a non-migratory passerine bird, resident in Europe, western Asia and North Africa. It is 34–39 cm long and has a body mass of 181–257 g. This species is not sexually dimorphic. The house sparrow is also a non-migratory passerine, native to most Europe. It is 14–18 cm long and has a body mass of 21–31 g. Although body mass does not differ between sexes, adults of this species present strong sexual dimorphism in plumage coloration [38].

The jackdaws were caught from March to July 2014 in ‘La Cañada de los Pájaros’ using a walk-in trap, while the house sparrows were caught using mist nets from April to August 2014 in the same location, and from June to August 2016 in different localities from the Huelva Province. Birds were individually ringed with numbered metal rings weighed and blood sampled from the jugular vein using sterile syringes. The volume of blood obtained differed between species due to differences in body mass (1 ml in jackdaws and 0.2 ml in house sparrows). Female birds with brood patches were released immediately after capture and were not included in this study to reduce any impact on their reproductive performance. The experimental feeding trials were undertaken from 7:30 to 12:00 h (GMT + 1 h).

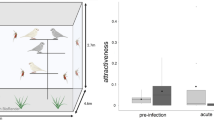

Individual birds were enclosed for 30 min in an insect cage (BugDorm-43030F, 32.5 × 32.5 × 32.5 cm, MegaView Science Co, Taichung, Taiwan) containing 53 ± 33.7 (mean ± SD) (range 1–152) mosquito females of either Cx. pipiens or Oc. caspius. The experimental feeding trials were developed in an environment with low light and no noise that could alter their behaviour. A number of previous studies have reported the ability of mosquito species including Cx. pipiens to feed on birds maintained in cages [39, 40]. Each bird was immobilized to prevent defensive behaviours against mosquitoes. Jackdaws were immobilized using non-permanent masking tape, with the wings attached to the body, the beak closed and legs held together. Un-feathered areas of the body (i.e. legs and eyes) remained uncovered during the trials, thus allowing mosquitoes to feed on the birds. House sparrows were immobilized using a cylinder made with 1 × 1 cm mesh, allowing mosquitoes to bite through. After the trials, birds were released at the same location of capture without any apparent sign of damage. Mosquitoes with a recent blood meal in their abdomen, including those showing partial and full engorgement, were counted and categorised as blood-fed mosquitoes.

Molecular analyses

Genomic DNA was extracted from bird blood samples using Maxwell® 16 LEV Blood DNA Kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) [41]. Birds were molecularly sexed following Griffiths et al. [42]. The Plasmodium infection status of birds was assessed by the amplification of a 478 bp fragment of the mitochondrial cytochrome b gene following Hellgren et al. [43]. The presence of amplicons was verified in 1.8% agarose gels and positive samples were sequenced using BigDye technology (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) or the Macrogen sequencing service (Macrogen Inc., Amsterdam, Netherlands). Sequences were edited using the software Sequencher™ v.4.9 (Gene Codes Corp., Ann Arbor, MI, USA) and assigned to parasite genus after comparison with the GenBank database (National Centre for Biotechnology Information). Only birds infected with avian Plasmodium were included in this study, while birds infected or co-infected with Haemoproteus or Leucocytozoon were removed from the analysis.

We characterized the occurrence of Cx. pipiens biotypes in the area (i.e. La Cañada de los Pájaros) where larvae were collected in the context of other study. We used 140 mosquitoes captured and amplified the 5’ flanking region of the CQ11 microsatellite following [44, 45]. We found that Cx. p. pipiens, Cx. p. molestus and their hybrids were present in the area (frequency of 45, 10.7 and 44.3%, respectively). The biotypes of mosquitoes included in this study where not analysed due to the large sample size.

Statistical analysis

The proportion of mosquitoes that bit house sparrows and jackdaws were compared separately for the two-mosquito species using Chi-square tests. We used generalized mixed linear models (GLMMs) with binomial error and logit link function to assess the effect of mosquito species and bird characteristics on mosquito biting rates. Analyses were performed in R software v.3.2.5 [46] with the package lme4 [47]. First, we compared the biting rates of the two mosquito species on birds. Models included the mosquito biting rate as the dependent variable, expressed as the number of mosquitoes that bit on the focal bird with respect to the number of mosquitoes that did not bite this individual using the cbind function. Due to the differences in the method used to immobilize each bird species and their clear differences in body size, separated models were fitted for jackdaws and house sparrows. In each case, bird body mass and the date (day 1 = 1st January) on which each trial was conducted were included as covariates and bird sex, Plasmodium infection status (infected/uninfected) and mosquito species (Cx. pipiens/Oc. caspius) were included as fixed factors. Because house sparrows were captured in two different years, the variable year was included as a fixed factor in the model assessing the biting rate of mosquitoes exposed to this bird species. We also included the two-way interactions between mosquito species and host sex and between mosquito species and infection status in the models. Bird identity was included as a random term to correct for the overdispersion shown when using both binomial and quasibinomial distributions (dispersion parameter > 7.21) [48]. The variables body mass and date were scaled for each species by the standard deviation and mean-centred to normalize the variable distribution. The jackdaw population studied here was subjected to a medication experiment with birds either injected immediately before exposure to mosquitoes with a sub-curative dose of primaquine or treated as controls. This treatment did not affect the mosquito biting rate (Z = -1.2, Estimate = -0.62, P = 0.26), thus this factor was not included in further analyses. The potential effect of the different Plasmodium lineages on the mosquito biting rate was not analysed due to the low sample size available for the different combinations between bird and mosquito species (see Table 1).

Results

Seventy-two jackdaws (34 males and 38 females) and 101 house sparrows (66 males and 35 females) were included in this study. Of these, 30 jackdaws (41.7%) and 55 house sparrows (54.5%) were infected with avian Plasmodium. Overall, 7 Plasmodium lineages were detected (Table 1). A total of 9153 mosquito females were exposed to the birds, including 6387 Cx. pipiens and 2766 Oc. caspius. Of these, 630 (9.9%) Cx. pipiens and 633 (22.9%) Oc. caspius fed on blood (Table 2), including 294 (46.7%) Cx. pipiens and 436 (68.9%) Oc. caspius which fed on jackdaws and 336 (53.3%) Cx. pipiens and 197 (31.1%) Oc. caspius which fed on house sparrows (Table 2).

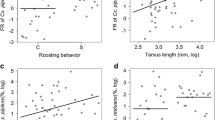

The biting rate of Oc. caspius on jackdaws was higher than on house sparrows (χ2 = 15.43, df = 1, P < 0.001), while no differences were found for Cx. pipiens (χ2 = 0.04, df = 1, P = 0.84; Fig. 1). The mammophilic Oc. caspius showed a significantly higher biting rate than the ornithophilic Cx. pipiens (Z = 4.22, Estimate = 1.00, P < 0.001; Fig. 1).

The effects of bird traits on mosquito biting rates were studied separately for each bird species because of the differential methodology (i.e. immobilization) used in each species and the differences reported above. In the case of jackdaws, Oc. caspius showed a significantly higher biting rate than Cx. pipiens (Table 3). In addition, Oc. caspius showed a higher biting rate on female than on male jackdaws, while non-statistically significant differences were found for Cx. pipiens (Table 3, Fig. 1). Host infection status by avian Plasmodium, body mass and date were not significantly related to mosquito biting rates (Table 3). For house sparrows, we found no differences in the biting rate between Cx. pipiens and Oc. caspius. Date was the only variable significantly related to mosquito biting rate, with an increase in biting rates as the seasons progressed. Host sex, body mass and infection status by avian Plasmodium were not significantly related to mosquito biting rates on house sparrows (Table 3, Fig. 1).

Discussion

Identifying the potential causes underlying the non-random biting patterns of mosquitoes is essential to understand the dynamics of transmission of avian Plasmodium and other vector-borne pathogens [13]. Here, we tested how three important avian traits (i.e. body mass, sex and the infection status by Plasmodium) in two bird species affect the biting rates of two mosquito species potentially involved in the transmission of avian malaria parasites [32]. Nonetheless, other factors not quantified in this study, such as the size of the blood meal, could also be important in the parasite transmission success and should be therefore considered in future studies.

The biting rate of the mammophilic Oc. caspius on jackdaws was higher than the biting rate of the ornithophilic Cx. pipiens, while non-significant differences were found when mosquitoes faced house sparrows. Although most of the blood meals of Oc. caspius analysed in different studies was derived from mammals, birds including chickens and house sparrows represented between 9.1–19.9% of the blood meals in this species [6, 49]. This pattern clearly contrasts with that of Cx. pipiens, for which birds represent between 85.1–91.67% of the blood meals [6]. In this study, the Cx. pipiens biotypes were not considered although potential differences in the feeding preferences have been reported [50]. However, mosquitoes in this study were captured in an area where the two biotypes (Cx. pipiens pipiens and Cx. pipiens molestus) and their hybrids coexist. A previous study conducted in southern Spain did not find significant differences in the proportion of blood meals from birds between Culex pipiens biotypes [45]. Our results clearly support the ability of Oc. caspius to feed on birds, at least when they are not allowed to choose between other host classes (i.e. mammals). This fact is especially relevant as our study focuses on the biting rate of mosquitoes and not on the feeding preferences of these species. Contrary to Cx. pipiens, Oc. caspius is traditionally considered as an aggressive mosquito and an important nuisance to human populations [51], but experimental studies supporting this assumption are scarce. Differences in the biting rate between mosquito species could be associated with their life history traits and breeding requirements, especially those related to the availability of water sources. While Oc. caspius depends on tidal cycles and uses temporal flooded areas for larval development [52], Cx. pipiens uses more permanent water sources [53] and, consequently, their life-cycle may be less time-constrained. In addition, it is possible that a differential activity pattern between mosquito species could have affected our results, with Oc. caspius showing a strong peak of activity during the day while Cx. pipiens peaks its activity at night and sunset [49]. Although this possibility could potentially explain the differences found between species, the biting rates of Cx. pipiens found in this study are similar to those found in a previous experiment developed during the night [30]. The variation in climatic conditions throughout the year is expected to affect the phenology of both the host and the vector and thus may potentially influence the host-vector interactions. We found that mosquito biting rates increased over time (i.e. from spring to autumn), but only when exposed to house sparrows. In this regard, Edman [54] reported differences in the feeding patterns of Culex nigripalpus depending on the season. In our case, this effect seems to be associated to particular host-mosquito assemblages, since it was apparent in only one of the two bird species studied. Nevertheless, it is important to highlight that the relevance of this variable should be considered low, as the model including the significant effect of the date explained only 7% of the variance.

The fact that differences in biting patterns were only detected when mosquitoes faced jackdaws, the larger host species, suggests these may be related to differences in the amounts of cues emitted by each bird species. In close proximity to their hosts, the relevance of visual and thermo-sensory stimulation of mosquitoes increases with respect to larger distances. Moreover, the use of multiple sensory cues may increase the likelihood of mosquito feeding success [3]. Due to their larger size, jackdaws may emit a higher amount of attractants, including CO2, heat and odours, than house sparrows, potentially leading to the differences found here.

Previous studies have reported a positive relationship between host body mass and biting rates of blood-sucking insects [19, 55], although this pattern usually corresponds to studies comparing different host species. As expected from its larger size, jackdaws were bitten at a higher rate than house sparrows by Oc. caspius, although we did not find significant differences for Cx. pipiens. The amount of bare skin exposed, usually positively correlated with body mass, may affect mosquito feeding success [56]. In fact, body mass was a key variable explaining the prevalence of infection by the mosquito-borne pathogen West Nile virus in birds [57]. Further support for this possibility can be derived from the study by Yan et al. [58], who found that Cx. pipiens fed more often on birds with longer tarsus, suggesting that larger areas of exposed skin are important for determining biting patterns. In this respect, Burkett-Cadena et al. [39] found that the proportion of bites on nestlings with respect to the adult female in the nest increased as they grow, suggesting that size in addition to the exposed skin may be key factors influencing mosquito feeding patterns. However, we did not find any significant relationship between the biting rate of mosquitoes and bird body mass at the intraspecific level. In this regard, Lalubin et al. [29] found that the attraction of Cx. pipiens to house sparrows was not significantly associated with their body mass. This suggests that, at short distances, the slight intraspecific differences in body mass are probably less important than other cues determining mosquito bites, like heat, humidity or odour [3].

As predicted, host sex influenced the biting rates of Oc. caspius mosquitoes when facing jackdaws. However, and in contrast to our prediction, this mosquito species preferred to bite females than males, but these differences were not found when mosquitoes were exposed to house sparrows. The biting rates of Cx. pipiens were not significantly related to host sex. Burkett-Cadena et al. [25] found male-biased blood meals in mosquitoes (64% of the blood meals analysed derived from male birds), although they suggest this could be due to skewed sex ratios in wild birds. However, there are not significant sex-biased differences in the feeding patterns of bird-biting mosquitoes, including Culex species [25]. Moreover, Simpson et al. [20] concluded that bird sex has no effect on the probability of Cx. pipiens choosing an individual over its partner. The preference of mammophilic mosquitoes for a particular sex of bird could be associated with the sexual differences in the composition of odour profiles. Among other factors, the volatile and non-volatile substances of the secretions of the preen gland may affect the feeding preferences of blood-sucking insects [59, 60] and their composition differ between bird sexes [61, 62]. Differences in the response of Oc. caspius and Cx. pipiens to secretions of the preen gland could explain, at least in part, discrepancies found between mosquito species [63].

We did not find support for a relationship between avian Plasmodium infection status and mosquito biting rates. In view of previously reported results, it is unclear whether avian malaria infection enhances [26, 27] or decreases [29] the mosquito attraction towards the infected host. Thus, the host manipulation hypothesis pointing to an increase in Plasmodium transmission success through a higher attractiveness of infected hosts to mosquito bites remains an open question [64, 65]. Different authors have used diverse experimental procedures to test for the effect of avian infections on mosquito attraction; some of these are summarized in Table 4. For example, some authors have used dual-port olfactometers [29] while others have allowed mosquitoes to bite birds exposed under different situations (e.g. immobilized birds) [26, 27], with all these differences potentially affecting the conclusions obtained. In addition, different host-vector assemblages have been used, including different species of wild and domestic birds and insect vectors [26, 27, 29, 30, 66, 67]. Moreover, the results of our study should be interpreted with caution, as the host individuals used in our experiments were naturally infected with different lineages of Plasmodium and probably were in different stages of infection, which could potentially affect host attractiveness for vectors. Due to the low prevalence of some Plasmodium lineages in birds, we were unable to analyse possible differences in the effects of the different Plasmodium lineages on mosquito feeding preference. However, as far we know, no previous study has found differential bird attractiveness for vectors depending on the avian Plasmodium linage infecting them. In addition to changes in the amount and quality of cues emitted by infected hosts, differences in the intensity of defensive behaviour associated with the infection status might explain differences in their susceptibility to mosquito attacks [68, 69]. For example, Day et al. [68] found that malaria-infected mice were more lethargic and less likely to defend against mosquitoes. In our study, birds did not show symptoms of lethargy and all were immobilized to prevent anti-mosquito defensive behaviour. Therefore, the possibility of changes in host defensive behaviour owing to Plasmodium infection was ruled out in this study. Additionally, it is possible that the potential differences in the emission of cues between infected and uninfected hosts [70] can only be appreciated by mosquitoes at large distances, when host-seeking behaviour is mainly based on olfactory clues [3] or may be only evidenced when performing dual-choice experiments [26], which is not the case for our study.

Conclusions

This study highlights that the magnitude and direction of the effects of host traits such as body mass, sex or the infection status by the mosquito-borne avian Plasmodium on the feeding patterns of mosquitoes are far from being generalizable. Only sex was associated to differences in mosquito biting rates, and this effect was only detected for one of the mosquito species studied here. Consequently, the biting patterns of mosquitoes may differ according to vector and host species characteristics. The reasons underlying the preference of mammophilic mosquitoes for individuals of a particular sex are unclear and need detailed analyses with regard, for instance, to the olfactory cues released by male and female birds.

References

Takken W, Knols BG. Odor-mediated behavior of Afrotropical malaria mosquitoes. Annu Rev Entomol. 1999;44:131–57.

Lehane MJ. The biology of blood-sucking in insects. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2005.

Raji JI, DeGennaro M. Genetic analysis of mosquito detection of humans. Curr Opin Insect Sci. 2017;20:34–8.

Molaei G, Andreadis TG, Armstrong PM, Diuk-Wasser M. Host-feeding patterns of potential mosquito vectors in Connecticut, USA: molecular analysis of bloodmeals from 23 species of Aedes, Anopheles, Culex, Coquillettidia, Psorophora, and Uranotaenia. J Med Entomol. 2007;45:1143–51.

Burkett-Cadena ND, Graham SP, Hassan HK, Guyer C, Eubanks MD, Katholi CR, et al. Blood feeding patterns of potential arbovirus vectors of the genus Culex targeting ectothermic hosts. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;79:809–15.

Muñoz J, Ruiz S, Soriguer R, Alcaide M, Viana DS, Roiz D, et al. Feeding patterns of potential West Nile virus vectors in south-west Spain. PLoS One. 2012;7:e39549.

Takken W, Verhulst NO. Host preferences of blood-feeding mosquitoes. Annu Rev Entomol. 2013;58:433–53.

Martínez de la Puente J, Muñoz J, Capelli G, Montarsi F, Soriguer R, Arnoldi D, et al. Avian malaria parasites in the last supper: identifying encounters between parasites and the invasive Asian mosquito tiger and native mosquito species in Italy. Malar J. 2015;14:32.

Kilpatrick AM, Kramer LD, Jones MJ, Marra PP, Daszak P. West Nile virus epidemics in North America are driven by shifts in mosquito feeding behavior. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e82.

Hamer GL, Kitron UD, Goldberg TL, Brawn JD, Loss SR, Ruiz MO, et al. Host selection by Culex pipiens mosquitoes and West Nile virus amplification. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;80:268–78.

Lura T, Cummings R, Velten R, De Collibus K, Morgan T, Nguyen K, Gerry A. Host (avian) biting preference of southern California Culex mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae). J Med Entomol. 2012;49:687–96.

Rizzoli A, Bolzoni L, Chadwick EA, Capelli G, Montarsi F, Grisenti M, et al. Understanding West Nile virus ecology in Europe: Culex pipiens host feeding preference in a hotspot of virus emergence. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:213.

Liebman KA, Stoddard ST, Reiner RC Jr, Perkins TA, Astete H, Sihuincha M, et al. Determinants of heterogeneous blood feeding patterns by Aedes aegypti in Iquitos, Peru. PLoS Neglect Trop Dis. 2014;8:e2702.

VanderWaal KL, Ezenwa VO. Heterogeneity in pathogen transmission: mechanisms and methodology. Funct Ecol. 2016;30:1606–22.

Dye C. The analysis of parasite transmission by bloodsucking insects. Annu Rev Entomol. 1992;37:1–19.

Gillies MT, Wilkes TJ. The range of attraction of animal baits and carbon dioxide for mosquitoes. Studies in a freshwater area of West Africa. B Entomol Res. 1972;61:389–404.

Torr SJ, Mangwiro TNC, Hall DR. The effects of host physiology on the attraction of tsetse (Diptera: Glossinidae) and Stomoxys (Diptera: Muscidae) to cattle. Bull Entomol Res. 2006;96:71–84.

Martínez de la Puente J, Merino S, Lobato E, Rivero-de Aguilar J, del Cerro S, Ruiz-de-Castañeda R, et al. Nest-climatic factors affect the abundance of biting flies and their effects on nestling condition. Acta Oecol. 2010;36:543–7.

Schönenberger AC, Wagner S, Tuten HC, Schaffner F, Torgerson P, Furrer S, et al. Host preferences in host-seeking and blood-fed mosquitoes in Switzerland. Med Vet Entomol. 2016;30:39–52.

Simpson JE, Folsom-O’Keefe CM, Childs JE, Simons LE, Andreadis TG, Diuk-Wasser MA. Avian host-selection by Culex pipiens in experimental trials. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7861.

Zuk M, Thornhill R, Ligon JD, Johnson K. Parasites and mate choice in red jungle fowl. Am Zool. 1990;30:235–44.

Skorping A, Jensen KH. Disease dynamics: all caused by males? Trends Ecol Evol. 2004;19:219–20.

Zuk M, Stoehr AM. Sex differences in susceptibility to infection: an evolutionary perspective. In: Klein SL, Roberts CW, editors. Sex hormones and immunity to infection. Berlin: Springer; 2010. p. 1–17.

Calero-Riestra M, García JT. Sex-dependent differences in avian malaria prevalence and consequences of infections on nestling growth and adult condition in the Tawny pipit, Anthus campestris. Malar J. 2016;15:178.

Burkett-Cadena ND, Bingham AM, Unnasch TR. Sex-biased avian host use by arbovirus vectors. R Soc Open Sci. 2014;1:140262.

Cornet S, Nicot A, Rivero A, Gandon S. Malaria infection increases bird attractiveness to uninfected mosquitoes. Ecol Lett. 2013;16:323–9.

Cornet S, Nicot A, Rivero A, Gandon S. Both infected and uninfected mosquitoes are attracted toward malaria infected birds. Malar J. 2013;12:179.

Batista EPA, Costa EFM, Silva AA. Anopheles darlingi (Diptera: Culicidae) displays increased attractiveness to infected individuals with Plasmodium vivax gametocytes. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:251.

Lalubin F, Bize P, van Rooyen J, Christe P, Glaizot O. Potential evidence of parasite avoidance in an avian malarial vector. Anim Behav. 2012;84:539–45.

Yan J, Martínez de la Puente J, Gangoso L, Gutiérrez-López R, Soriguer R, Figuerola J. Avian malaria infection intensity influences mosquito feeding patterns. Int J Parasitol. 2018;48:257–64.

Santiago-Alarcon D, Palinauskas V, Schaefer HM. Diptera vectors of avian haemosporidian parasites: untangling parasite life cycles and their taxonomy. Biol Rev. 2012;87:928–64.

Ferraguti M, Martínez de la Puente J, Muñoz J, Roiz D, Ruiz S, Soriguer R, et al. Avian Plasmodium in Culex and Ochlerotatus mosquitoes from southern Spain: effects of season and host-feeding source on parasite dynamics. PLoS One. 2013;8:e66237.

Hellgren O, Pérez-Tris J, Bensch S. A jack of all trades and still a master of some: prevalence and host range in avian malaria and related blood parasites. Ecology. 2009;90:2840–9.

Drovetski SV, Aghayan SA, Mata VA, Lopes RJ, Mode NA, Harvey JA, et al. Does the niche breadth or trade-off hypothesis explain the abundance-occupancy relationship in avian haemosporidia? Mol Ecol. 2014;23:3322–9.

Schaffner E, Angel G, Geoffroy B, Hervy JP, Rhaiem A, Brunhes J. The mosquitoes of Europe: an identification and training programme. Montpellier: IRD Editions; 2001.

Franks SJ, Pratt PD, Tsutsui ND. The genetic consequences of a demographic bottleneck in an introduced biological control insect. Conserv Genet. 2011;12:201–11.

Lagisz M, Port G, Wolff K. Living in a jar: genetic variation and differentiation among laboratory strains of the red flour beetle. J Appl Entomol. 2011;135:682–92.

Svensson L, Mullarney K, Zetterström D. Collins bird guide. British birds. 2nd ed. London: HarperCollins; 2010.

Burkett-Cadena ND, Ligon RA, Liu M, Hassan HK, Hill GE, Eubanks MD, Unnasch TR. Vector-host interactions in avian nests: do mosquitoes prefer nestlings over adults? Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;83:395–9.

Gutiérrez-López R, Martínez de la Puente J, Gangoso L, Yan J, Soriguer R, Figuerola J. Do mosquitoes transmit the avian malaria-like parasite Haemoproteus? An experimental test of vector competence using mosquito saliva. Parasit Vectors. 2016;9:609.

Gutiérrez-López R, Martínez de la Puente J, Gangoso L, Soriguer R, Figuerola J. Comparison of manual and semi-automatic DNA extraction protocols for the barcoding characterization of hematophagous louse flies (Diptera: Hippoboscidae). J Vector Ecol. 2015;40:11–5.

Griffiths R, Double MC, Orr K, Dawson RJ. A DNA test to sex most birds. Mol Ecol. 1998;7:1071–5.

Hellgren O, Waldenström J, Bensch S. A new PCR assay for simultaneous studies of Leucocytozoon, Plasmodium, and Haemoproteus from avian blood. J Parasitol. 2004;90:797–802.

Di Luca M, Toma L, Boccolini D, Severini F, La Rosa G, Minelli G, et al. Ecological distribution and CQ11 genetic structure of Culex pipiens complex (Diptera: Culicidae) in Italy. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0146476.

Martínez de la Puente J, Ferraguti M, Ruiz S, Roiz D, Soriguer RC, Figuerola J. Culex pipiens forms and urbanization: effects on blood feeding sources and transmission of avian Plasmodium. Malar J. 2016;15:589.

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. 2017. https://www.R-project.org/. Accessed 15 Sept 2018.

Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker B, Walker S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J Stat Softw. 2015;67:1–48.

Harrison XA. Using observation-level random effects to model overdispersion in count data in ecology and evolution. PeerJ. 2014;2:e616.

Balenghien T, Fouque F, Sabatier P, Bicout DJ. Horse-, bird-, and human-seeking behavior and seasonal abundance of mosquitoes in a West Nile virus focus of southern France. J Med Entomol. 2006;43:936–46.

Fritz ML, Walker ED, Miller JR, Severson DW, Dworkin I. Divergent host preferences of above- and below-ground Culex pipiens mosquitoes and their hybrid offspring. Med Vet Entomol. 2015;29:115–23.

Gutsevich AV, Monchadskii AS, Shtakelberg AA. Fauna of the USSR, Diptera, mosquitoes family Culicidae. Moscow: Academy of Sciences of the USSR; 1974. p. 1974.

Ezanno P, Aubry-Kientz M, Arnoux S, Cailly P, L’Ambert G, Toty C, et al. A generic weather-driven model to predict mosquito population dynamics applied to species of Anopheles, Culex and Aedes genera of southern France. Prev Vet Med. 2015;120:39–50.

Roiz D, Ruiz S, Soriguer R, Figuerola J. Climatic effects on mosquito abundance in Mediterranean wetlands. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:333.

Edman JD. Host-feeding patterns of Florida mosquitoes: III. Culex (Culex) and Culex (Neoculex). J Med Entomol. 1974;11:95–104.

Estep LK, McClure CJ, Burkett-Cadena ND, Hassan HK, Unnasch TR, Hill GE. Developing models for the forage ratios of Culiseta melanura and Culex erraticus using species characteristics for avian hosts. J Med Entomol. 2012;49:378–87.

Mooring MS, Benjamin JE, Harte CR, Herzog NB. Testing the interspecific body size principle in ungulates: the smaller they come, the harder they groom. Anim Behav. 2000;60:35–45.

Figuerola J, Jiménez-Clavero MA, López G, Rubio C, Soriguer R, Gómez-Tejedor C, Tenorio A. Size matters: West Nile virus neutralizing antibodies in resident and migratory birds in Spain. Vet Microbiol. 2008;132:39–46.

Yan J, Gangoso L, Martínez de la Puente J, Soriguer R, Figuerola J. Avian phenotypic traits related to feeding preferences in two Culex mosquitoes. Sci Nat. 2017;104:76.

Russell CB, Hunter FF. Attraction of Culex pipiens/restuans (Diptera: Culicidae) mosquitoes to bird uropygial gland odors at two elevations in the Niagara region of Ontario. J Med Entomol. 2005;42:301–5.

Martínez de la Puente J, Rivero-de Aguilar J, del Cerro S, Argüello A, Merino S. Do secretions from the uropygial gland of birds attract biting midges and black flies? Parasitol Res. 2011;109:1715–8.

Jacob J, Balthazart J, Schoffeniels E. Sex differences in the chemical composition of uropygial gland waxes in domestic ducks. Biochem Syst Ecol. 1979;7:149–53.

Amo L, Avilés JM, Parejo D, Peña A, Rodriguez J, Tomás G. Sex recognition by odour and variation in the uropygial gland secretion in starlings. J Anim Ecol. 2012;81:605–13.

Allan SA, Bernier UR, Kline DL. Laboratory evaluation of avian odors for mosquito (Diptera: Culicidae) attraction. J Med Entomol. 2006;43:225–31.

Hurd H. Manipulation of medically important insect vectors by their parasites. Annu Rev Entomol. 2003;48:141–61.

Lefèvre T, Lebarbenchon C, Gauthier-Clerc M, Misse D, Poulin R, Thomas F. The ecological significance of manipulative parasites. Trends Ecol Evol. 2009;24:41–8.

Tomás G, Merino S, Martínez de la Puente J, Moreno J, Morales J, Lobato E. Determinants of abundance and effects of blood-sucking flying insects in the nest of a hole-nesting bird. Oecologia. 2008;156:305–12.

Martínez de la Puente J, Merino S, Tomás G, Moreno J, Morales J, et al. Factors affecting Culicoides species composition and abundance in avian nests. Parasitology. 2009;136:1033–41.

Day JF, Ebert KM, Edman JD. Feeding patterns of mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) simultaneously exposed to malarious and healthy mice, including a method for separating blood meals from conspecific hosts. J Med Entomol. 1983;20:120–7.

Shirasu M, Touhara K. The scent of disease: volatile organic compounds of the human body related to disease and disorder. J Biochem. 2011;150:257–66.

Kelly M, Su CY, Schaber C, Crowley JR, Hsu FF, Carlson JR, et al. Malaria parasites produce volatile mosquito attractants. MBio. 2015;6:e00235–315.

Acknowledgements

We thank A. Díez, M. Ferraguti, L. Gómez, I. Martín, A. Pastoriza, E. Pérez, S. Ruiz and J. Yan for helping during field and laboratory work. P. Rodríguez and M. Adrián allowed us to sample mosquito larvae and birds in “La Cañada de los Pájaros”. We would also like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments on the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by projects CGL2012-30759 and CGL2015-65055-P from the Spanish Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad and European Regional Development’s funds (FEDER) and by project P11-RNM-7038 from the Junta de Andalucía. RGL was supported by a FPI grant (BES-2013-065274). JMP was partially supported by a Juan de la Cierva contract and a 2017 Leonardo Grant for Researchers and Cultural Creators, BBVA Foundation. The Foundation accepts no responsibility for the opinions, statements and contents included in the project and/or the results thereof, which are entirely the responsibility of the authors. LG was supported by a Marie Curie Fellowship of the European Commission (grant number 747729 “EcoEvoClim”).

Availability of data and materials

Data supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article. The datasets used and/or analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Authors’ contributions

All authors designed the study. RGL and JMP conducted the experimental work. RGL and JMP performed the laboratory analyses. RGL, JMP, LG and JF performed the statistical analyses. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All experimental procedures were approved by the CSIC Ethics committee and Animal Health authorities (439-2016) and complied with Spanish laws.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Gutiérrez-López, R., Martínez-de la Puente, J., Gangoso, L. et al. Effects of host sex, body mass and infection by avian Plasmodium on the biting rate of two mosquito species with different feeding preferences. Parasites Vectors 12, 87 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-019-3342-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-019-3342-x