Abstract

Background

The male gamete fertilization factor P48/45 in malaria parasites is a prime transmission-blocking vaccine (TBV) candidate. Efforts to develop antimalarial vaccines are often thwarted by genetic diversity of the target antigens. Here we evaluated the genetic diversity of Pvs48/45 gene in global Plasmodium vivax populations.

Methods

We determined 200 Pvs48/45 sequences collected from temperate and subtropical parasite populations in China. Population genetic and evolutionary analyses were performed to determine the levels of genetic diversity, potential signature of selection, and population differentiation.

Results

Analysis of the Pvs48/45 sequences from 200 P. vivax parasites collected in a temperate and a tropical region revealed a low level of genetic diversity (π = 0.0012) with 14 single nucleotide polymorphisms, of which 11 were nonsynonymous. Analysis of 344 Pvs48/45 sequences from nine worldwide P. vivax populations detected a total of 38 haplotypes, of which 13 haplotypes were present only once. Multiple tests for selection confirmed a signature of positive selection on Pvs48/45 with selection skewed to the second cysteine domain. Haplotype network analysis and Wright’s fixation index showed large geographical differentiation with the presence of continent-or region-specific mutations in this gene.

Conclusions

Pvs48/45 displays low levels of genetic diversity with the presence of region-specific mutations. Some of the mutations may be potential epitope targets based on their positions in the predicted structure, highlighting the need for future evaluation of these mutations in designing Pvs48/45-based TBV.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Plasmodium vivax has the widest geographical distribution of the human malarias. With as much as 19 % of the global populations being at risk of P. vivax infections [1–3], P. vivax has been increasingly recognized as a significant threat to global health. P. vivax is the most prevalent malaria parasites in China and distributed in both temperate and subtropical areas. The subtropical Yunnan province has year-round transmission of P. vivax and P. falciparum, whereas the central, temperate provinces such as Anhui have seasonal transmission of only P. vivax. A decade ago, the central provinces have experienced malaria resurgence, characterized by local outbreaks of the temperate-zone P. vivax malaria parasite with long relapse intervals [4–6]. This highlights the resilience of vivax malaria to control measures and underlines this parasite as a significant challenge for malaria elimination.

Interruption of malaria transmission is considered a priority task in the course of malaria elimination [7]. However, P. vivax produces gametocytes earlier, allowing transmission before manifestation of the symptoms in patients. In this case, transmission-blocking vaccines (TBVs) are more suitable for interrupting parasite transmission [8]. A number of candidate targets for transmission-blocking immunity such as P25 and P28 [9, 10], P48/45 [11, 12] and P230 [13, 14] have been assessed. Pfs230 and Pfs48/45 are major gametocyte and gamete surface antigens that naturally induce acquired immunity in malaria-exposed individuals [15, 16]. They are members of 6-Cys protein family [17–19], which includes additional eight members. P48/45, P47 and P230 play an essential role in gamete fertility [12, 20]. The presence of multiple disulfide bridges in the 6-Cys domains of P48/45 has hampered evaluation of the immunogenicity of the recombinant P48/45 due to difficulties to achieve proper folding of the protein. Recently, the full-length recombinant Pfs48/45 has been successfully expressed in Escherichia coli, which maintains functional antigenicity and induces potent transmission-blocking antibodies in mice and non-human primates [11, 21]. Similarly, sera from animals immunized with the recombinant Pvs48/45 protein or DNA vaccine also produced significant transmission blocking activity [22, 23].

Many malaria parasite antigens display extensive genetic diversity as a result of host immune selection. Genetic polymorphisms in vaccine candidates hamper vaccine development, since they tend to elicit allele variant-specific immunity, allowing immune escape mutants. Analyses performed on several P. vivax TBV candidates such as Pvs230 [24], Pvs48/45 [25, 26], Pvs25 and Pvs28 [27, 28] and PvWARP [25, 29] showed limited sequence diversity. To date, the majority of the analysis was done on parasites from a limited number of locations, making large-scale and comparative studies highly relevant. In this study, we compared the genetic diversity of pvs48/45 genes from 200 clinical samples representing two distinct parasite populations in subtropical Yunnan Province and temperate-zone Anhui Province of China.

Methods

Collection of P. vivax clinical samples

Clinical P. vivax samples were collected from patients with acute P. vivax malaria in 2004 in Yunnan and in 2008–2010 in both Yunnan and Anhui provinces. Finger-prick blood samples of microscopy confirmed P. vivax cases were blotted onto Whatman filter papers. Informed consent was obtained from patients or their guardians, while ethical clearance for sampling collection was approved by relevant ethical committees of collaborating institutions. Use of the samples for this study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of China Medical University.

DNA extraction, PCR and sequencing

Plasmodium DNA was extracted from 210 filter papers using QIAamp DNA Mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Primers and amplification of the pvs48/45 open reading frame (ORF) were described in Additional file 1: Table S1. PCR was performed using KOD plus DNA polymerase (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan) with strong 3′ – 5′ proofreading activity. All PCR products were purified with the QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and sequenced in both directions using the ABI Prism® BigDye™ cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Ten sequences with double peaks on the electrophoregrams suggesting of mixed infection were removed from subsequent analysis. DNA sequences obtained were assembled using the Lasergene software (DNASTAR, Madison, WI, USA) with manual editing and aligned with the Sal I reference sequence (PVX_083235) using ClustalW. Sequence data were deposited in the GenBank (KT267361-KT267560).

Genetic diversity

Orthologs of Pvs48/45 from other malaria parasite species P. cynomolgi (Pcs48/45; PCYB_121700), P. knowlesi (Pks48/45; PKH_120750), P. berghei (Pbs48/45; PBANKA_135960), P. chabaudi (Pchs48/45; PCHAS_136420), P. yoelii (Pys48/45; PY17X_1365300), P. falciparum (Pfs48/45; PF3D7_1346700) and P. reichenowi (Prs48/45; PRCDC_1345700) were retrieved from PlasmoDB (www.plasmodb.org). Sequences were aligned using CLUSTALW with manual editing. All the analyses in this study were done using DnaSP v5 software [30] and MEGA6 [31] except specified otherwise. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using the Neighbor-Joining method with 1000 pseudo-replications [32]. Polymorphisms were estimated by the number of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and the average number of pairwise nucleotide differences per site (π). Distribution of π across the full-length gene was visualized by sliding window plot using a window size of 100 and step size of 25 bp. To understand differential pattern of diversity throughout the gene, Pvs48/45 sequences were divided into three regions: i) domain I (142–483 bp), ii) domain II (892–1254 bp), and iii) inter-domain region (484–891 bp).

Tests of neutrality

To investigate departure from neutrality, we performed Tajima’s D analysis [33, 34]. Under neutrality, Tajima’s D is expected to be 0. Significantly positive Tajima’s D values indicate recent population bottleneck or balancing selection, whereas negative values suggest population expansion or directional selection. The difference between the non-synonymous substitutions per non-synonymous site (dN) and numbers of synonymous substitutions per synonymous site (dS) was estimated using the modified Nei and Gojobori method [35]. Statistical significance of the difference was estimated using Z-test. A sliding window approach with a window size of 100 and a step size of 25 bp was used to highlight specific regions of Pvs48/45 that deviate from neutral expectations. Five likelihood based algorithms: SLAC [36], FEL [36], IFEL [37], and REL [36] methods implemented in Datamonkey webserver [38] were used to identify the existence of positive selection pressure at individual codons. Sites were considered under positive selection if the dN - dS are indicated with high statistical significance (P <0.1 and Bayes factor >50).

We also used McDonald-Kreitman (MK) test to examine departure from neutrality [39]. The MK test compares the ratio of non-synonymous to synonymous substitutions (dN/dS) with polymorphic difference (within species; KS) and fixed difference (between closely related species; Ka). Pcs48/45 and Pks48/45 sequences were used as outgroups in this test. Fisher’s exact test was used to assess statistical significance. The null hypothesis of MK test assumes dN/dS = Ka/Ks under neutrality, whereas dN/dS < Ka/Ks signifies negative selection. A sliding window approach was also used to identify specific regions of Pvs48/45 that deviate from neutral expectations using a window size of 10 and a step size of 5 bp.

Inter-population genetic differentiation

To understand the global distribution of diversity in Pvs48/45 gene, 200 Pvs48/45 sequences from China were analyzed together with 144 published sequences obtained from GenBank and PlasmoDB. The geographical origins of the 344 sequences are: China (n = 200, this study), Thailand (n = 26), Korea (n = 40), Columbia (n = 28), Mexico (n = 15), Peru (n = 19), India (n = 3), Indonesia (n = 3) [26], Vanuatu (n = 9) and Sal I. To estimate the proportion of genetic variance due to population subdivision, Wright’s fixation index [40] of interpopulation variance in allele frequencies (Fst) was calculated. The number of haplotypes were estimated from all the isolates and the haplotype network was constructed (excluding singleton haplotypes) by NETWORK (fluxus-engineering.com) using the median joining algorithm [41].

Results

Divergence of P45/48 genes among Plasmodium species

P48/45 is involved in male gamete fertility and is evolutionarily conserved in Plasmodium species. The full-length ORF of Pvs48/45 is 1353 bp encoding 450 amino acids (aa), and contains two copies of the s48-45 six-Cys domain located at positions 48–162 aa and 298–418 aa, respectively. The s45-48 domain comprises of ~120 amino acids with six positionally conserved cysteine residues [42]. To understand the evolutionary history of P48/45 among Plasmodium species, orthologs from P. vivax (Sal I strain), P. cynomolgi, P. knowlesi, P. berghei, P. chabaudi, P. yoelii, P. falciparum and P. reichenowi were used for comparison. Alignment of these P48/45 sequences revealed 15 conserved cysteine residues (Fig. 1) with the exception of P. cynomolgi P48/45, which lost one residue due to a 17 bp deletion (positions 297 to 313). Of the total 15 Cys residues, five are present in s48/45 domain I, six in domain II and four in the inter-domain region (Figs. 1, 2a). Among these eight Plasmodium species, P. falciparum is the only species that contains six cysteine residues in both s48/45 domain I and domain II (Figs. 1, 2a), indicating that cysteine residue found at position 35 in domain I might have generated in the P. falciparum lineage after divergence from its other sister species. Moreover, P. chabaudi contained two more cysteine residues that are present in the region outside the s48-45 domains (Figs. 1, 2a).

Sequence alignment of P48/45 from eight Plasmodium species. The s48/45 domain I and II are boxed (corresponding to the Pvx_083235 domain boundaries). Cysteine residues are highlighted in red. P48/45 amino acid sequences used are from P. vivax (PVX_083235), P. cynomolgi (PCYB_121700), P. knowlesi (PKH_120750), P. berghei (PBANKA_135960), P. chabaudi (PCHAS_136420), P. yoelii (PY17X_1365300), P. falciparum (PF3D7_1346700) and P. reichenowi (PRCDC_1345700)

The lengths of P48/45 protein sequences of the eight Plasmodium species varied from 455 (three rodent parasite species) to 434 residues in P. cynomolgi (Fig. 2a). The similarity between sequences was highest between P. falciparum and P. reichenowi (96.88 %), and lowest between P. knowlesi and P. yoelii (50.44 %) (Fig. 2b). A phylogenetic tree generated from amino acid sequences revealed three monophylectic branches, which conforms to earlier report of the phylogeny of the Plasmodium group based on other genetic markers [43]. P. vivax, P. cynomolgi and P. knowlesi formed a cluster, while P. falciparum was clustered with P. reichenowi (Fig. 2c). The third branch included the three rodent species.

Divergence of P48/45 gene sequence among Plasmodium species. a Schematic domain organization of P48/45 in each species. The numbers of cysteine residues in each domain are indicated. b Percentage of sequence similarity between amino acid sequences of eight Plasmodium species. c Neighbor-Joining tree of P48/45 amino acid sequences from eight Plasmodium species. Bootstrap values generated from 1000 replicates are shown

Genetic diversity of Pvs48/45 from the Chinese isolates

We obtained near full-length Pvs48/45 sequences (31–1332 bp) from 200 P. vivax Chinese isolates, including 61 samples collected from the temperate Anhui province in 2008–2010 and 139 samples collected from the subtropical Yunnan province. Compared to the Sal I reference sequence, there are 14 SNPs, 11 of which were non-synonymous that resulted in amino acid changes (K26R, E35K, Y196H, H211N, K250N, T273S, D335Y, A376T, I380T, G381V, and K418R) (Additional file 1: Table S2). Out of 14 SNPs, only 12 were polymorphic among 200 samples from China, while two mutations (H211N and K250N) were fixed. Four of these mutations were observed in all three populations, while six and one SNP were specific to Yunnan 08–10 and Anhui population, respectively (Fig. 3a). Three new mutations (Y196H, T273S and G381V) were identified among the Chinese isolates; the latter two were singletons.

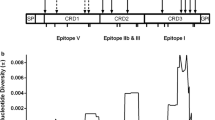

Patterns of nucleotide diversity and natural selection on Pvs48/45. a Schematic diagram of Pvs45/48 gene showing positions of 12 SNPs (black bars) identified in the Chinese isolates. Symbols above bars represent SNPs observed in each population. The singletons have been highlighted in red. b Sliding window analysis of average pairwise nucleotide diversity (π). c dn/ds calculated using 200 P. vivax isolates. A window size of 100 bp and a step size of 25 bp were used for the window plot analysis

Overall nucleotide diversity (π) in the 200 samples was 0.0012, which was similar to that observed in Yunnan 08–10, while slightly higher than those in the other two populations (Table 1). To understand the pattern of nucleotide diversity across the gene, Pvs48/45 was divided into three blocks: two s48-45 domains separated by an inter domain. Sliding window analysis showed that these three domains were considerably different in nucleotide diversity (Fig. 3b). We identified 9 SNPs in domain II and 5 in inter-domain region, whereas s48-45 domain I was absolutely conserved in all the three populations. Nucleotide diversity was higher in domain II (π = 0.002) as compared to the inter-domain (π =0.0008) (Table 1, Fig. 3b). A similar pattern of diversity was observed in Yunnan 08–10 and Anhui samples. Among the three populations, Yunnan 08–10 samples had the highest nucleotide diversity (Table 1).

Based on the amino acid sequences, a total of 15 haplotypes were observed in the 200 parasite isolates (Additional file 1: Table S3). Significant differences existed in the number of haplotypes and prevalence of individual haplotypes between the three study populations. Yunnan 08–10 samples had the highest haplotype diversity with 12 haplotypes. Three haplotypes (hap1-3) were shared among the three parasite populations. Hap2 was the most prevalent haplotype in the Yunnan 04 samples with 64.1 % prevalence, but it was rare in the Yunnan 08–10 and Anhui samples. In comparison, hap3 was much more prevalent in the Yunnan 08–10 and Anhui samples. The Yunnan 08–10 samples had seven unique haplotypes not present in the other two populations, of which hap7 reached 16.0 % prevalence.

Departure from neutrality

Multiple tests were performed on the near full-length as well as individual blocks of Pvs48/45 to determine whether this gene has been under natural selection. Tajima’s D values were not significant for any domains (Table 1). However, there were still differences among sites and between different domains of Pvs48/45. For example, in most cases, the Tajima’s D values were negative, suggesting the presence of rare alleles at low frequencies in these populations. Yet, in some cases, these alleles had reached higher frequencies, giving rise to a positive D value (e.g., interdomain in Yunnan 2004 samples). For the full-length sequence, dN was significantly higher than dS in all the populations. Likewise, dN/dS was significantly greater than 1 in domain II of the 200 samples and the samples from Anhui. Positive selection on domain II was also demonstrated by the sliding window plot of dN/dS values (Fig. 3c), which clearly showed dN/dS values of >1 in s48/45 domain II, indicating positive selection on this block. This was further supported by the positively selected sites identified by the codon-based tests (Additional file 1: Table S3). Three sites were identified under positive selection by different tests, of which two are present in domain II (Additional file 1: Table S4).

MK test was used for comparing intraspecific polymorphism (dN/dS) and interspecific divergence (Ka/KS) using sequences from two phylogenetically related species P. cynomolgi and P. knowlesi. Significant values of dN/dS > Ka/KS were observed in the full-length gene, revealing excessive accumulation of synonymous substitutions between species (data not shown), which could be interpreted as negative selection for maintaining protein structure by eliminating all deleterious mutations. However, when MK test was performed on domain II and the inter-domain, this excess was significant for domain II only in the Anhui samples (Table 1). A sliding window for Ka/Ks obtained by comparing the P. vivax sequences to sequences of P. cynomolgi and P. knowlesi identified Ka/Ks value > 1 in signal sequence and inter-domain region (Fig. 4), thereby indicating the presence of positive selection in these two blocks.

Geographic differentiation of worldwide P. vivax populations

To evaluate Pvs48/45 diversity in worldwide P. vivax populations, the 200 Chinese Pvs48/45 sequences were analyzed together with 144 publically available Pvs48/45 sequences from nine worldwide P. vivax populations, including sequences from five Asian (Thailand, China, Korea, India and Indonesia), four American (Peru, Mexico, Columbia and Sal I), and one Oceania (Vanuatu) countries. Genetic differentiation among parasite populations was examined using Fst, the Wright’s fixation index of inter-population variance in allele frequencies. The two parasite populations collected in 2008–2010 from Yunnan and Anhui provinces had low genetic differentiation (Fst = 0.098), suggesting of extensive genetic exchanges between these populations. However, significant population differentiation was observed between the Yunnan 04 parasites and the two populations collected in 2008–2010 (Fst = 0.290 and 0.366, respectively). Overall the Fst estimate of the worldwide populations was 0.665, indicating that about 67 % of the variation was apportioned between parasite populations (Table 2). Pairwise comparisons between populations revealed a wide range of Fst values (0.34 – 0.90) between populations from different continents compared to that observed within continents (0.01 – 0.43) (Table 2). Genetic differentiation between populations relative to each continent was also evident from the haplotype network constructed from the worldwide haplotypes (Fig. 5). A total of 38 haplotypes were identified within the 344 sequences, of which 13 singleton haplotypes (observed only once) were excluded from the analysis. The clustered distribution of the haplotypes relevant to the continent of origin is apparent from the haplotype network (Fig. 5).

Network of the Pvs48/45 haplotypes from global P. vivax populations. The size of the pies reflects the frequency of a particular haplotype. The lengths of the lines connecting the pies, measured from their centers, are in proportion to the number of base pair substitutions separating the haplotypes. Color represents different countries. Haplotypes observed in different continents are encircled

Discussion

Host immunity plays an important role in shaping the genetic repertoire of malaria parasite antigens. Understanding genetic diversity of these antigens is essential for designing antimalarial vaccines [44, 45]. In the present study, we analyzed 200 Pvs48/45 sequences of clinical P. vivax samples from two geographical regions of China and compared them with Pvs48/45 sequences from other endemic regions. The phylogenetic tree based on P48/45 sequences agreed well with those constructed with the mitochondrial genomes and 18 s rRNA genes [43, 46]. Despite the levels of sequence similarity between species varied from 50.44 % to 96.88 %, the positions of cysteine residues in the gene were highly conserved, supporting a generalizing feature of the 6-Cys gene family. Within P. vivax, 11 amino acid changes were observed between the Chinese samples and the Sal I reference strain, while two of them were fixed among the 200 isolates from China (Additional file 1: Table S2). In addition, seven of the 11 amino acid changes were parsimony informative (observed in more than one sequence). Eight of these mutations are previously known from other Asian countries [25, 26], while one novel mutation (Y196H) was observed in all the three populations from China. Mutations H211N, K250N and K418R have been previously identified as important targets for vaccine design based on their structural positions [26]. In our populations, mutations H211N and K250N are fixed while K418R is present in 97 % of the total isolates (193 out of 200).

Like other sexual stage antigens, Pvs48/45 exhibited low levels of genetic diversity. The measure of nucleotide diversity (0.0012) is in a similar range with other sexual stage antigens such as Pvs25 (0.0013) in China [28] and worldwide Pvs230 (0.00118) [24]. Pvs48/45 was even more conserved in the Korean populations where nucleotide diversity varied from 0.00147 [26] to 0.00053 [25]. The level of genetic diversity was at par between the two parasite populations in China, whereas parasites from Yunnan province appeared to have increased genetic diversity over the years (Table 1). Interestingly, however, seven out of 11 amino acid changes commonly observed in the samples collected at different time intervals were either fixed or highly frequent (frequency varying from 36-100 %) except Y196H mutation, which was less frequent in the later populations collected in 2008–10. Four mutations that were observed only in 2008–10 were rare with frequency varying from 1 % to 7 %. These mutations might be the result of difference in the number of samples collected at the two time points and/or recently increased parasite introduction from neighboring malaria endemic countries due to heightened cross-country human migration. This similar pattern of diversity in space and time further suggests that the low-level genetic diversity in Pvs48/45 seems to be imposed by natural selection acting to maintain the functional/structural characteristics of this protein.

Immunoepidemiological studies of sexual stage, pre-fertilization, antigens such as P230 and P48/45 showed that antibody responses to these proteins are present in endemic human populations, and are associated with transmission blocking activities [16, 47–49]. As such, it is expected that these antigens are under host immune selection, which may lead to significant genetic polymorphisms in antigens. Previous studies suggested positive selection on sexual stage antigens such as the male and female gamete fertilization factors Pfs47 and Pfs48/45 [50]. Similarly, our data demonstrated positive selection on Pvs48/45. Moreover, distribution of the polymorphic sites is not even across the gene, but rather concentrated in domain II of this gene and domain I was monomorphic. This might be due to the differential selection pressure acting on two domains because of their specific functions or differential exposure to host immunity [51]. On the other hand, Ka/KS rate showed values greater than 1 in regions outside of the two s48-45 domains. This inter-species pattern of selection might be the consequence of long-term evolution of each species within their respective hosts. This is in contrast to another 6-Cys, gamete-surface antigen pvs230, which was found to be under purifying selection [24]. Such divergent selections on two male gamete surface proteins might be due to differences in their functional constraints, as P48/45 is involved in binding to female gametes [12] and P230 mediates binding of red blood cells [52]. It is also noteworthy that the MK analysis showed significant accumulation of inter-species synonymous substitutions, suggesting that Pvs48/45 might have diverged from P. knowlesi and P. cynomolgi due to negative selection acting on deleterious mutations. Similar patterns of evolution have been reported in other members of 6-Cys family [24, 53].

In P. falciparum, merozoite antigens have high levels of diversity globally but less geographical isolation possibly due to host immune selection [45]. Data obtained in P. vivax such as PvTRAP, PvDBP and PvAMA-1 also supported such a conclusion [54]. In contrast, non-merozoite antigens such as sexual stage antigen Pfs48/45 showed significant geographical differentiation, possibly as a result of gene flow barriers or/and divergent selection on the amino acid sequences of these proteins in different populations [55]. Similarly, analysis of worldwide Pvs48/45 sequences revealed evident genetic structure between geographical parasite populations as shown by relatively high fixation indices. Inter-continent F ST values are much higher than those of parasites within a continent. In China, despite the geographical separation of Yunnan and Anhui provinces, the prevalence of different mutations and haplotypes were similar between the two parasite populations collected in recent years (2008–2010) from these two localities, with differences being present only in rare alleles such as the singleton mutations. However, compared with the earlier parasite population collected in Yunnan in 2004, there were major allele changes, reflected in the emergence of the I380T mutations in the later populations and significantly reduced prevalence of the Y196H mutations. Taken together, although worldwide Pvs48/45 genes displayed a high-level sequence conservation, continent-or region-specific mutations exist in different population, especially in the second s48-45 domain, which was apparently under positive selection. Therefore, precautions need to be taken when designing TBV against Pvs48/45.

Conclusions

Pvs48/45 displays low levels of genetic diversity with the presence of region-specific mutations. Some of the mutations may be potential epitope targets based on their positions in the predicted structure, highlighting the need for future evaluation of these mutations in designing Pvs48/45-based TBV.

References

Battle KE, Gething PW, Elyazar IR, Moyes CL, Sinka ME, Howes RE, et al. The global public health significance of Plasmodium vivax. Adv Parasitol. 2012;80:1–111.

Gething PW, Elyazar IR, Moyes CL, Smith DL, Battle KE, Guerra CA, et al. A long neglected world malaria map: Plasmodium vivax endemicity in 2010. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6:e1814.

WHO. World Malaria Report 2014. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014.

Sleigh AC, Liu XL, Jackson S, Li P, Shang LY. Resurgence of vivax malaria in Henan Province, China. Bull World Health Organ. 1998;76:265–70.

Xu BL, Su YP, Shang LY, Zhang HW. Malaria control in Henan Province, People’s Republic of China. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;74:564–7.

Zhou SS, Wang Y, Tang LH. Malaria situation in the People’s Republic of China in 2006. Chin J Parasitol Parasitic Dis. 2007;25:439–41.

Alonso PL, Brown G, Arevalo-Herrera M, Binka F, Chitnis C, Collins F, et al. A research agenda to underpin malaria eradication. PLoS Med. 2011;8.

Guttery DS, Holder AA, Tewari R. Sexual development in Plasmodium: lessons from functional analyses. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002404.

Barr PJ, Green KM, Gibson HL, Bathurst IC, Quakyi IA, Kaslow DC. Recombinant Pfs25 protein of Plasmodium falciparum elicits malaria transmission-blocking immunity in experimental animals. J Exp Med. 1991;174:1203–8.

Hisaeda H, Stowers AW, Tsuboi T, Collins WE, Sattabongkot JS, Suwanabun N, et al. Antibodies to malaria vaccine candidates Pvs25 and Pvs28 completely block the ability of Plasmodium vivax to infect mosquitoes. Infect Immun. 2000;68:6618–23.

Outchkourov NS, Roeffen W, Kaan A, Jansen J, Luty A, Schuiffel D, et al. Correctly folded Pfs48/45 protein of Plasmodium falciparum elicits malaria transmission-blocking immunity in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:4301–5.

Van Dijk MR, Janse CJ, Thompson J, Waters AP, Braks JA, Dodemont HJ, et al. A central role for P48/45 in malaria parasite male gamete fertility. Cell. 2001;104:153–64.

Tachibana M, Sato C, Otsuki H, Sattabongkot J, Kaneko O, Torii M, et al. Plasmodium vivax gametocyte protein Pvs230 is a transmission-blocking vaccine candidate. Vaccine. 2012;30:1807–12.

Tachibana M, Wu Y, Iriko H, Muratova O, MacDonald NJ, Sattabongkot J, et al. N-terminal prodomain of Pfs230 synthesized using a cell-free system is sufficient to induce complement-dependent malaria transmission-blocking activity. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2011;18:1343–50.

Ouedraogo AL, Roeffen W, Luty AJ, De Vlas SJ, Nebie I, Ilboudo-Sanogo E, et al. Naturally acquired immune responses to Plasmodium falciparum sexual stage antigens Pfs48/45 and Pfs230 in an area of seasonal transmission. Infect Immun. 2011;79:4957–64.

Bousema T, Roeffen W, Meijerink H, Mwerinde H, Mwakalinga S, Van Gemert GJ, et al. The dynamics of naturally acquired immune responses to Plasmodium falciparum sexual stage antigens Pfs230 & Pfs48/45 in a low endemic area in Tanzania. PLoS One. 2010;5:e14114.

Carter R, Coulson A, Bhatti S, Taylor BJ, Elliott JF. Predicted disulfide-bonded structures for three uniquely related proteins of Plasmodium falciparum, Pfs230, Pfs48/45 and Pf12. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1995;71:203–10.

Templeton TJ, Kaslow DC. Identification of additional members define a Plasmodium falciparum gene superfamily which includes Pfs48/45 and Pfs230. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1999;101:223–7.

Gerloff DL, Creasey A, Maslau S, Carter R. Structural models for the protein family characterized by gamete surface protein Pfs230 of Plasmodium falciparum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:13598–603.

Van Dijk MR, Van Schaijk BC, Khan SM, Van Dooren MW, Ramesar J, Kaczanowski S, et al. Three members of the 6-cys protein family of Plasmodium play a role in gamete fertility. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000853.

Chowdhury DR, Angov E, Kariuki T, Kumar N. A potent malaria transmission blocking vaccine based on codon harmonized full length Pfs48/45 expressed in Escherichia coli. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6352.

Arevalo-Herrera M, Vallejo AF, Rubiano K, Solarte Y, Marin C, Castellanos A, et al. Recombinant Pvs48/45 antigen expressed in E. coli generates antibodies that block malaria transmission in Anopheles albimanus mosquitoes. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0119335.

Tachibana M, Suwanabun N, Kaneko O, Iriko H, Otsuki H, Sattabongkot J, et al. Plasmodium vivax gametocyte proteins, Pvs48/45 and Pvs47, induce transmission-reducing antibodies by DNA immunization. Vaccine. 2015;33:1901–8.

Doi M, Tanabe K, Tachibana S, Hamai M, Tachibana M, Mita T, et al. Worldwide sequence conservation of transmission-blocking vaccine candidate Pvs230 in Plasmodium vivax. Vaccine. 2011;29:4308–15.

Kang JM, Ju HL, Moon SU, Cho PY, Bahk YY, Sohn WM, et al. Limited sequence polymorphisms of four transmission-blocking vaccine candidate antigens in Plasmodium vivax Korean isolates. Malar J. 2013;12:144.

Woo MK, Kim KA, Kim J, Oh JS, Han ET, An SS, et al. Sequence polymorphisms in Pvs48/45 and Pvs47 gametocyte and gamete surface proteins in Plasmodium vivax isolated in Korea. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2013;108:359–67.

Tsuboi T, Kaslow DC, Gozar MM, Tachibana M, Cao YM, Torii M. Sequence polymorphism in two novel Plasmodium vivax ookinete surface proteins, Pvs25 and Pvs28, that are malaria transmission-blocking vaccine candidates. Mol Med. 1998;4:772–82.

Feng H, Zheng L, Zhu X, Wang G, Pan Y, Li Y, et al. Genetic diversity of transmission-blocking vaccine candidates Pvs25 and Pvs28 in Plasmodium vivax isolates from Yunnan Province. China Parasit Vectors. 2011;4:224.

Gholizadeh S, Djadid ND, Basseri HR, Zakeri S, Ladoni H. Analysis of von Willebrand factor A domain-related protein (WARP) polymorphism in temperate and tropical Plasmodium vivax field isolates. Malar J. 2009;8:137.

Baird JK, Hoffman SL. Iron supplementation in prevention of severe anaemia and malaria. Lancet. 1997;350:1855. author reply 6.

Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. MEGA6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30:2725–9.

Baird JK, Hoffman SL. Prevention of malaria in travelers. Med Clin North Am. 1999;83:923–44. vi.

Tajima F. Statistical method for testing the neutral mutation hypothesis by DNA polymorphism. Genetics. 1989;123:585–95.

Watterson GA. On the number of segregating sites in genetical models without recombination. Theor Popul Biol. 1975;7:256–76.

Nei M, Gojobori T. Simple methods for estimating the numbers of synonymous and nonsynonymous nucleotide substitutions. Mol Biol Evol. 1986;3:418–26.

Baird JK, Surjadjaja C. Consideration of ethics in primaquine therapy against malaria transmission. Trends Parasitol. 2011;27:11–6.

Baker DA. Cyclic nucleotide signalling in malaria parasites. Cell Microbiol. 2011;13:331–9.

Delport W, Poon AF, Frost SD, Kosakovsky Pond SL. Datamonkey 2010: a suite of phylogenetic analysis tools for evolutionary biology. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2455–7.

McDonald JH, Kreitman M. Adaptive protein evolution at the Adh locus in Drosophila. Nature. 1991;351:652–4.

Wright S. The genetical structure of populations. Ann Eugen. 1951;15:323–54.

Bandelt HJ, Forster P, Rohl A. Median-joining networks for inferring intraspecific phylogenies. Mol Biol Evol. 1999;16:37–48.

Annoura T, Van Schaijk BC, Ploemen IH, Sajid M, Lin JW, Vos MW, et al. Two Plasmodium 6-Cys family-related proteins have distinct and critical roles in liver-stage development. FASEB J. 2014;28:2158–70.

Escalante AA, Freeland DE, Collins WE, Lal AA. The evolution of primate malaria parasites based on the gene encoding cytochrome b from the linear mitochondrial genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:8124–9.

Arevalo-Herrera M, Chitnis C, Herrera S. Current status of Plasmodium vivax vaccine. Hum Vaccin. 2010;6:124–32.

Barry AE, Schultz L, Buckee CO, Reeder JC. Contrasting population structures of the genes encoding ten leading vaccine-candidate antigens of the human malaria parasite, Plasmodium falciparum. PLoS One. 2009;4.

Hayakawa T, Culleton R, Otani H, Horii T, Tanabe K. Big bang in the evolution of extant malaria parasites. Mol Biol Evol. 2008;25:2233–9.

Bousema JT, Roeffen W, van der Kolk M, De Vlas SJ, van de Vegte-Bolmer M, Bangs MJ, et al. Rapid onset of transmission-reducing antibodies in javanese migrants exposed to malaria in papua, indonesia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;74:425–31.

Drakeley CJ, Bousema JT, Akim NI, Teelen K, Roeffen W, Lensen AH, et al. Transmission-reducing immunity is inversely related to age in Plasmodium falciparum gametocyte carriers. Parasite Immunol. 2006;28:185–90.

Jones S, Grignard L, Nebie I, Chilongola J, Dodoo D, Sauerwein R, et al. Naturally acquired antibody responses to recombinant Pfs230 and Pfs48/45 transmission blocking vaccine candidates. J Infect. 2015;71:117–27.

Anthony TG, Polley SD, Vogler AP, Conway DJ. Evidence of non-neutral polymorphism in Plasmodium falciparum gamete surface protein genes Pfs47 and Pfs48/45. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2007;156:117–23.

Putaporntip C, Jongwutiwes S, Sakihama N, Ferreira MU, Kho WG, Kaneko A, et al. Mosaic organization and heterogeneity in frequency of allelic recombination of the Plasmodium vivax merozoite surface protein-1 locus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:16348–53.

Eksi S, Czesny B, Van Gemert GJ, Sauerwein RW, Eling W, Williamson KC. Malaria transmission-blocking antigen, Pfs230, mediates human red blood cell binding to exflagellating male parasites and oocyst production. Mol Microbiol. 2006;61:991–8.

Forero-Rodriguez J, Garzon-Ospina D, Patarroyo MA. Low genetic diversity and functional constraint in loci encoding Plasmodium vivax P12 and P38 proteins in the Colombian population. Malar J. 2014;13:58.

Chenet SM, Tapia LL, Escalante AA, Durand S, Lucas C, Bacon DJ. Genetic diversity and population structure of genes encoding vaccine candidate antigens of Plasmodium vivax. Malar J. 2012;11:68.

Conway DJ, Machado RL, Singh B, Dessert P, Mikes ZS, Povoa MM, et al. Extreme geographical fixation of variation in the Plasmodium falciparum gamete surface protein gene Pfs48/45 compared with microsatellite loci. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2001;115:145–56.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

YMC and LWC conceived of the study and helped to draft the manuscript. YMY and QF collected the blood spots specimens. HF carried out the studies, statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. BG carried out the molecular genetic studies and drafted the manuscript. MLW, WQZ, LZ, XTZ participated in the sequence alignment. EJL and QF helped with statistical analysis. TT helped with critically revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript and approved the submitted version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work was supported by NIAID, National Institutes of Health (U19 AI089672 and R01 AI099611).

Hui Feng and Bhavna Gupta contributed equally to this work.

Additional file

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Primers used for PCR and sequencing of Pvs48/45. Table S2. Nonsynonymous mutations and their frequencies [n (%)] in different parasite populations collected in China. Table S3. Pvs48/45 haplotypes and their frequencies in Anhui and Yunnan provinces. Table S4. Selection pressure analysis of the 200 Pvs48/45 sequences (434 codons) using the SLAC, FEL, IFEL and REL methods employed in the Datamonkey server. (DOC 73 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Feng, H., Gupta, B., Wang, M. et al. Genetic diversity of transmission-blocking vaccine candidate Pvs48/45 in Plasmodium vivax populations in China. Parasites Vectors 8, 615 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-015-1232-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-015-1232-4