Abstract

Background

It remains elusive how the characteristics, the course of disease, the clinical management and the outcomes of critically ill COVID-19 patients admitted to intensive care units (ICU) worldwide have changed over the course of the pandemic.

Methods

Prospective, observational registry constituted by 90 ICUs across 22 countries worldwide including patients with a laboratory-confirmed, critical presentation of COVID-19 requiring advanced organ support. Hierarchical, generalized linear mixed-effect models accounting for hospital and country variability were employed to analyse the continuous evolution of the studied variables over the pandemic.

Results

Four thousand forty-one patients were included from March 2020 to September 2021. Over this period, the age of the admitted patients (62 [95% CI 60–63] years vs 64 [62–66] years, p < 0.001) and the severity of organ dysfunction at ICU admission decreased (Sequential Organ Failure Assessment 8.2 [7.6–9.0] vs 5.8 [5.3–6.4], p < 0.001) and increased, while more female patients (26 [23–29]% vs 41 [35–48]%, p < 0.001) were admitted. The time span between symptom onset and hospitalization as well as ICU admission became longer later in the pandemic (6.7 [6.2–7.2| days vs 9.7 [8.9–10.5] days, p < 0.001). The PaO2/FiO2 at admission was lower (132 [123–141] mmHg vs 101 [91–113] mmHg, p < 0.001) but showed faster improvements over the initial 5 days of ICU stay in late 2021 compared to early 2020 (34 [20–48] mmHg vs 70 [41–100] mmHg, p = 0.05). The number of patients treated with steroids and tocilizumab increased, while the use of therapeutic anticoagulation presented an inverse U-shaped behaviour over the course of the pandemic. The proportion of patients treated with high-flow oxygen (5 [4–7]% vs 20 [14–29], p < 0.001) and non-invasive mechanical ventilation (14 [11–18]% vs 24 [17–33]%, p < 0.001) throughout the pandemic increased concomitant to a decrease in invasive mechanical ventilation (82 [76–86]% vs 74 [64–82]%, p < 0.001). The ICU mortality (23 [19–26]% vs 17 [12–25]%, p < 0.001) and length of stay (14 [13–16] days vs 11 [10–13] days, p < 0.001) decreased over 19 months of the pandemic.

Conclusion

Characteristics and disease course of critically ill COVID-19 patients have continuously evolved, concomitant to the clinical management, throughout the pandemic leading to a younger, less severely ill ICU population with distinctly different clinical, pulmonary and inflammatory presentations than at the onset of the pandemic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In March 2020, the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic incepted, leading to the largest international health crisis in recent history [1]. Within an impressively short time, the international research community has gained a plethora of new insights regarding the time course of COVID-19 progression and the development of critical illness [2, 3]. Factors prognostic for an unfavourable disease course have been extensively investigated and have provided critical guidance for the pursuit of novel therapeutic approaches [4, 5].

Barely a few months after the pandemic’s outbreak, the first reports describing improvements in mortality in critically ill COVID-19 patients emerged [6,7,8]. However, such changes can be influenced by a multitude of factors including resource availability, novel therapies and changes in medical practice among others. Moreover, large regional differences have been reported [8,9,10]. How exactly the characteristics of patients admitted to intensive care units (ICU) and their course of disease have changed, and if such changes can be related to the clinical management and outcome of critically ill COVID-19 patients around the globe, remains elusive.

Evidence of dynamics in the phenotypical expression of COVID-19 critical illness could reveal indications for future preventive and therapeutic strategies and aid in assessing the quality of critical care that is delivered to date. Thus, the present study aimed to answer whether (I) the characteristics of critically ill COVID-19 patients at ICU admission, (II) the temporal course of COVID-19, (III) the clinical management and (IV) ICU outcomes have changed throughout the pandemic.

Methods

Study design

On 13 March 2020, the prospective observational Risk Stratification in COVID-19 patients in the ICU (RISC-19-ICU) registry was launched to capture COVID-19 features and track characteristics and outcomes of patients with SARS-CoV-2 infections admitted to ICUs [2, 11,12,13,14]. The registry (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04357275) has been endorsed by the Swiss Society of Intensive Care Medicine (https://www.sgi-ssmi.ch) and was exempt from the need for additional ethics approval and patient informed consent by the ethics committee of the University of Zurich (KEK 2020-00322). The study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki; the Guidelines on Good Clinical Practice (GCP-Directive) were issued by the European Medicines Agency, the Swiss law and Swiss regulatory authority requirements as well as the regulatory authority requirements in each participating country, and have been designed in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines for observational studies. The current analysis regarded all patients recorded by 90 centres, in 22 countries, comprising the RISC-19-ICU registry during the period from 1 March 2020 until 30 September 2021 (Additional file 1: e-Appendix 1).

Inclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria for the RISC-19-ICU registry were (I) a laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection by nucleic acid amplification according to the WHO-issued testing guidelines, and (II) severe manifestation of COVID-19 requiring treatment in an ICU, defined as a hospital ward specialized in the care of critically ill patients with the availability of organ support therapies including invasive mechanical ventilation and non-invasive ventilation.

Patient data collection

A standardized data set was prospectively collected during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic for all critically ill COVID-19 patients admitted to the collaborating centres. Data collection was performed through an anonymized electronic case report form managed by the REDCap electronic data capture tool hosted on a secure server by the Swiss Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Data were collected on the day of ICU admission, and on days 1, 2, 3, 5 and 7, including patient characteristics, vital parameters, arterial blood gas analyses and laboratory values, such as inflammatory, coagulation, renal, liver and cardiac markers, treatment modalities and organ support therapies including the use of mechanical ventilation.

Data transformation

Calculation of the disease severity scores Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE II), Simplified Acute Physiology Score II (SAPS II) and Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) scores as well as the ventilatory ratio [15], a surrogate measure for physiological dead space, was performed using an openly available code library associated with the registry.

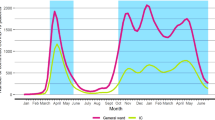

In order to allow a discrete numerical summary of the pandemic’s dynamics, apart from modelling time continuously, we sub-divided the pandemic into distinct periods. Three pandemic periods were defined based on the visual analysis of the pandemic’s peaks and SARS-CoV-2 variants in the individual countries composing the registries population (Additional file 1: e-Figure 1–3): Period 1 (1 March 2020 to 30 September 2020), Period 2 (1 October 2020 to 31 January 2021) and Period 3 (1 February 2021 to 30 September 2021). Only variables with a missing rate below 70% were included in the analysis; for a full reporting of missing rates, please refer to Additional file 1: e-Table 1.

Maximum differences (Δlate-early) of vitals and laboratory parameters between ICU admission, day 0 and day 5 of the ICU stay were calculated as follows: \(\Delta_{{{\text{late}} - {\text{early}}}} = X \times \left\{ {\max \left( {Y_{Day3} ,Y_{Day5} } \right) - {\text{min}}\left( {Y_{{{\text{Day0}}}} ,Y_{{{\text{Day1}}}} } \right)} \right\} + \left( {1 - X} \right)*\left\{ {\min \left( {Y_{{{\text{Day3}}}} ,Y_{{{\text{Day5}}}} } \right) - \max \left( {Y_{{{\text{Day0}}}} ,Y_{{{\text{Day1}}}} } \right)} \right\}\) where \(Y_{Day}\) represents a specific severity score, vital or laboratory parameter at day \(\in \left\{ {0, 1, 3, 5} \right\}\) and \(X\) is a function such that \(X\left( {Y_{{{\text{Day}}}} } \right) = \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}c} 1 & {{\text{if}}\; \left[ {\left( {\frac{{Y_{{{\text{Day3}}}} + Y_{{{\text{Day5}}}} }}{2}} \right) - \left( {\frac{{Y_{{{\text{Day0}}}} + Y_{{{\text{Day1}}}} }}{2}} \right)} \right] > 0} \\ 0 & {{\text{otherwise}}} \\ \end{array} } \right.\).

Statistical analysis

Data were modelled by means of hierarchical generalized linear mixed-effect models considering the date of ICU admission as fixed effect while accounting for within-hospital and within-country group nesting, after asserting that the country effects did not introduce extreme effects that could be interpreted as overfitting. The date of ICU admission was modelled as a restricted cubic spline with 3 knots chosen on the 10th, 50th and 90th percentiles and 95% confidence intervals [16]. To analyse the differences in dynamics between ICU survivors and non-survivors, we tested for an interaction term and reported survivor status stratified results. The null hypothesis, formulated as the absence of temporal effect for a specific variable, was assessed by comparing two models (with and without splines) using analysis of deviance with Wald chi-squared tests. Continuous variables were assumed to be Gaussian-distributed, severity scores and time to admission were assumed to be Poisson-distributed, and binary variables to be binomially distributed.

Statistical analysis was performed through a fully scripted data management pathway using the R environment for statistical computing version 4.0.2 [17]. Due to the observational, prospective nature of this cohort study, no power calculations were performed [18]. A two-sided p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Figures were plotted excluding observations that exceeded the 25th (75th) percentile added to 1.5 times the interquartile range. Values are given as means with standard deviation ± SD, medians with interquartile ranges [IQR] or counts and percentages as appropriate.

Results

Overall

From 1 March 2020 until 30 September 2021, date of database closing for this analysis, 4041 critically ill COVID-19 patients were included in 90 centres over 22 countries into the RISC-19-ICU registry. The evolution of SARS-CoV-2 variants in the respective countries is depicted in Additional file 1: e-Figure 3. Similarly, the number of total hospitalized patients as well as patients requiring ICU care in selected countries participating in the registry is displayed in Additional file 1: Figure 4.

Overall, patients were mainly male (70%), aged 61 ± 14 years and presented with a body mass index (BMI) of 29 ± 6 kg/m2 (Table 1). They were admitted to the hospital a mean of 9 ± 12 days after symptom onset and had to be referred to the ICU 3 ± 13 days later. At ICU admission, 17% required vasopressor support and 42% were directly intubated and mechanically ventilated. Admission SOFA score amounted to 8 ± 5, and SAPS II and APACHE II scores were 36 ± 19 and 16 ± 8, respectively.

In total, 66% of all patients were invasively mechanically ventilated and 26% of the patients died during their ICU stay.

Demographics over the time course of the pandemic

One thousand seven hundred (42%) patients were admitted to the respective ICUs between March and September 2020, 1543 (38%) between October 2020 and January 2021, and 798 (20%) between February and September 2021 (Additional file 1: e-Figure 5).

Over the time course of the pandemic, severity scores at admission, namely SOFA (March 2020: 8.2 [7.6–9.0], September 2021: 5.8 [5.3–6.4]), age-corrected SAPS II (March 2020: 26 [24–29], September 2021: 19 [17–20]) and APACHE (March 2020: 12.5 [11.5–13.5], September 2021: 8 [7–9]), continuously decreased (p < 0.001) (Fig. 1, Additional file 1: e-Figure 6). The percentage of female patients admitted to the ICU started to increase after October 2020 and was highest in September 2021 (March 2020: 26 [23–29]%, October 2020: 26 [24–28]%, February 2021: 30 [28–33]%, September 2021: 41 [35–48]%, p < 0.001). On the other hand, while the mean age of patients increased during the first months of the pandemic, it steadily decreased after October 2020 (March 2020: 61 [60–63] years, October 2020: 64 [62–66] years, February 2021: 63 [61–65] years, September 2021: 55 [53–58] years, p < 0.001). Similarly, the average number of comorbidities remained constant until October 2020 and then proceeded to decrease until September 2021 (p < 0.001). Conversely, the latency between symptom onset and hospitalization (March 2020: 6.7 [6.2–7.2] days, October 2020: 7.7 [7.2–8.3] days, February 2021: 9.5 [8.8–10.3] days, September 2021: 9.7 [8.9–10.5] days, p < 0.001) as well as between hospital and ICU admission (March 2020: 1.7 [1.4–2.1] days, October 2020: 2.3 [1.9–2.8] days, February 2021: 3.6 [3.0–4.4] days, September 2021: 4.0 [3.3–5.0] days, p < 0.001) steadily increased until February 2021 and then remained constant for the remainder of the studied period.

Dynamics of baseline characteristics over the pandemic. Mean effects over the time course of the pandemic, calculated by means of generalized mixed-effect models, are depicted by a red continuous line. 95% confidence intervals of the effect are depicted as shaded red area. The given p values originate from an analysis of deviance. Continuous variables are represented by topographic density plots, in which the intensity of the grayscale colouring indicates the highest concentration of values. Categorical variables are represented by violin plots, in which the segmental width of the plot correlates with the concentration of values

Vitals and laboratory findings at ICU admission

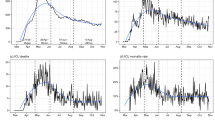

Contrasting with the decreasing severity scores, patients admitted to the ICU presented continuously lower paO2/FiO2 ratios (March 2020: 132 [123–141] mmHg, October 2020: 131 [124–140] mmHg, February 2021: 120 [112–129] mmHg, September 2021: 101 [91–113] mmHg, p < 0.001) along with increasing ventilatory ratios (p = 0.01); these effects became especially pronounced after October 2020 (Fig. 2, Additional file 1: e-Figure 7). By contrast, D-dimer levels at ICU admission continuously decreased from March 2020 to September 2021 (March 2020: 1722 [1320–2241] μg/l, October 2020: 1581 [1276–1953] mmHg, February 2021: 988 [763–1272] mmHg, September 2021: 506 [338–759] mmHg, p < 0.001). Notably, whereas C-reactive protein and procalcitonin levels did remain constant between March 2020 and September 2021, ferritin levels decreased until August 2020 and then remained constant for the remainder of the pandemic. Conversely, leucocyte (March 2020: 8.1 [7.6–8.7] 109/l, October 2020: 8.9 [8.3–9.5] 109/l, February 2021: 9.8 [9.1–10.5] 109/l, September 2021: 9.1 [8.2–10.1] 109/l, p < 0.001) and neutrophil counts increased until August 2020 and then continuously decreased for the remainder of the pandemic (p < 0.001), whereas lymphocyte counts remained constant until August 2020 and then showed a similar decreasing dynamic as leucocytes and neutrophils (p = 0.08).

Dynamics of vitals and laboratory parameters at intensive care unit admission. Mean effects over the time course of the pandemic, calculated by means of generalized mixed-effect models, are depicted by a red continuous line. 95% confidence intervals of the effect are depicted as shaded red area. The given p values originate from an analysis of deviance. Variables are represented by topographic density plots, in which the intensity of the grayscale colouring indicates the highest concentration of values

Disease progression over the ICU stay

Not only the admission characteristics, but also the dynamics of disease in response to ICU care can change over time. In order to capture these changes in disease progression over the first days of ICU stay, we computed the difference between day 5 and ICU admission and evaluated the change of this parameter (Δlate-early) over time.

At later stages of the pandemic, the PaO2/FiO2 ratio increased more pronouncedly during the first 5 days of ICU stay (March 2020: Δlate-early 34 [20–48] mmHg, October 2020: Δlate-early 29 [18–38] mmHg, February 2021: Δlate-early 37 [25–50] mmHg, September 2021: Δlate-early 70 [41–100] mmHg, p = 0.05), whereas the ventilatory ratio decreased more markedly (p < 0.001) (Fig. 3, Additional file 1: e-Figure 8–9, Additional file 1: e-Table 2). Similarly, C-reactive protein progressively experienced a stronger declining effect over the duration of the pandemic (March 2020: Δlate-early − 29 [− 102 to 44] mg/l, October 2020: Δlate-early − 47 [− 105 to 13] mg/l, February 2021: Δlate-early − 127 [− 189 to − 68] mg/l, September 2021: Δlate-early − 231 [− 352 to − 109] mg/l, p = 0.001). However, neither D-Dimer, ferritin and procalcitonin levels, nor leucocyte, neutrophil or lymphocyte count dynamics varied over the time course of the pandemic.

Dynamics of the evolution of vital and laboratory parameters during the first 5 days of intensive care unit stay. To capture the changes in the dynamics of disease over the first days of intensive care unit stay, the difference of a variable between day 5 and day 1 is summarized as parameter (Delta) over time. Mean effects over the time course of the pandemic, calculated by means of generalized mixed-effect models, are depicted by a red continuous line. 95% confidence intervals of the effect are depicted as shaded red area. The given p values originate from an analysis of deviance. Variables are represented by topographic density plots, in which the intensity of the grayscale colouring indicates the highest concentration of values

Medication management

The use of hydroxychloroquine and ritonavir/lopinavir while widely employed in the first months of the pandemic, dropped to 0% by June 2020 (Fig. 4). Similarly, therapeutic anticoagulation, whereas increasingly employed in the first year of the pandemic, experienced a decline during the second half of the pandemic (March 2020: 35 [24–48]%, October 2020: 77 [66–85]%, February 2021: 70 [57–80]%, September 2021: 45 [26–65]%, p < 0.001). Conversely, the use of corticosteroids increased steadily from 14 [9–22] in March 2020, reaching 86 [79–92] by October 2020 and 97 [94–99] by September 2021. Tocilizumab on the other hand was prescribed during the first months of the pandemic, but its prescription saw a halt between June 2020 and February 2021, after which its use steadily increased to 17 [5–47] in September 2021. Most prominently after February 2021, the proportion of vaccinated individuals admitted to the ICU steadily increased (p < 0.001) (Additional file 1: e-Figure 10).

Dynamics of medication management. Mean effects over the time course of the pandemic, calculated by means of generalized mixed-effect models, are depicted by a red continuous line. 95% confidence intervals of the effect are depicted as shaded red area. The given p values originate from an analysis of deviance

Organ support management and outcomes

The proportion of patients receiving invasive mechanical ventilation (March 2020: 82 [76–86], October 2020: 76 [70–82]%, February 2021: 70 [61–77]%, September 2021: 74 [64–82]%, p < 0.001) and renal replacement therapy decreased (March 2020: 12 [9–16], October 2020: 9 [7–12]%, February 2021: 5 [3–7]%, September 2021: 3 [1–9]%, p < 0.001) throughout the pandemic (Fig. 5, Additional file 1: e-Table 3–5). Conversely, more invasively ventilated patients were treated with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) at later stages of the pandemic (March 2020: 0.4 [0.1–1.3] %, October 2020: 0.5 [0.2–2]%, February 2021: 1 [0.4–3]%, September 2021: 3 [1–9]%, p < 0.001) (Fig. 4). Overall, more patients were treated with non-invasive mechanical ventilation (March 2020: 14 [11–18], October 2020: 25 [20–31]%, February 2021: 39 [32–46]%, September 2021: 24 [17–33]%, p < 0.001) and high-flow oxygen therapy (March 2020: 5 [4–7], October 2020: 10 [8–14]%, February 2021: 24 [19–31]%, September 2021: 20 [14–29]%, v0.001) as the pandemic progressed. Additionally, awake prone position was increasingly employed from February 2021 onwards (March 2020: 50 [43–58]%, October 2020: 47 [40–54]%, February 2021: 45 [38–52]%, September 2021: 52 [42–62]%, p < 0.001). Finally, ICU mortality initially worsened until June of 2020 and then progressively improved until September 2021 (March 2020: 23 [19–26], October 2020: 23 [19–26]%, February 2021: 29 [24–33]%, September 2021: 18 [12–24]%, p < 0.001), whereas length of ICU stay continuously decreased over the time course of the pandemic (March 2020: 14 [13–16], October 2020: 13 [12–15] days, February 2021: 12 [11–13] days, September 2021: 11 [10–13] days, p < 0.001).

Dynamics of organ support management and outcomes. Mean effects over the time course of the pandemic, calculated by means of generalized mixed-effect models, are depicted by a red continuous line. 95% confidence intervals of the effect are depicted as shaded red area. The given p values originate from an analysis of deviance. Continuous variables are represented by topographic density plots, in which the intensity of the grayscale colouring indicates the highest concentration of values. Categorical variables are represented by violin plots, in which the segmental width of the plot correlates with the concentration of values. IMV invasive mechanical ventilation

Development of differences between survivors and non-survivors over time

During the pandemic, patients surviving the ICU stay were characterized by a lower age than patients not surviving the ICU, albeit the difference in mean age decreased between March 2020 and October 2020 between both groups (p < 0.001) (Additional file 1: e-Figure 11). On the other hand, while non-survivors presented with higher SOFA scores at ICU admission during the whole pandemic, the difference in initial SOFA between non-survivors and survivors grew with the progress of the pandemic (p < 0.001).

The PaO2/FiO2 ratio at admission presented decreasing dynamics in both survivors and non-survivors during the pandemic (p < 0.001) (Additional file 1: e-Figure 12). Nevertheless, survivors were characterised by a more pronounced increase in PaO2/FiO2 ratio (p < 0.001) and had a stronger decrease in ventilatory ratio (p = 0.03) over the first 5 days of their ICU stay at later stages of the pandemic than non-survivors (Additional file 1: e-Figure 13). On the other hand, C-reactive protein (p < 0.001) as well as creatinine levels (p < 0.001) albeit lower at admission in survivors than non-survivors in March 2020 progressed to be similar in September 2021 (Additional file 1: e-Figure 12). Strikingly, C-reactive protein dynamics over the first days after ICU admission showed a more pronounced decline in non-survivors after June 2020, as compared to survivors (p < 0.001) (Additional file 1: e-Figure 13).

The proportion of survivors not being treated with mechanical ventilation decreased in the first year of the pandemic, to afterwards increase to its initial proportion by September 2021, while this effect was much less pronounced in non-survivors (p < 0.001) (Additional file 1: e-Figure 14). Conversely, more survivors than non-survivors were treated with high-flow oxygen over the course of the pandemic (v0.001), whereas a similar proportion of patients received non-invasive mechanical ventilation throughout the pandemic (p = 0.40). Interestingly, while survivors presented longer lengths of ICU stay than non-survivors in March 2020, this inverted with non-survivor requiring longer care in the ICU, especially during June 2020 and February 2021, as the pandemic progressed (p < 0.001).

Discussion

This analysis of the RISC-19-ICU registry confirms that the COVID-19 pandemic, especially regarding critically ill patients, has been and remains highly dynamic. Demographics, clinical characteristics, clinical management and outcomes of patients admitted to the ICU have been continuously changing over the last 19 months. Over time, critically ill COVID-19 patients have not only become younger, and increasingly female, but also the time span between symptom onset and ICU admission has become increasingly larger and their degree of overall organ dysfunction at ICU admission has decreased, despite worse initial oxygenation, along with a decrease in ICU mortality.

A plethora of hypotheses might explain these intriguing dynamics. The decrease in age of patients admitted to the ICU is probably a direct effect of the vaccination campaigns in the early 2021, which initially targeted mainly the elderly population [19]. However, more complex social aspects, such as the increasing non-compliance with public health measures of young adults, but not of elderly individuals, after extensive lockdowns and the high initial death toll on the most fragile elderly population, should also be considered [20]. Additionally, whilst the largely experimental antiviral and anti-inflammatory therapies employed in the early months of the pandemic failed to prove their efficacy [21, 22], the progressive use of dexamethasone after the publication of the RECOVERY landmark trial in June 2020 [4] as well as remdesivir in November 2020 [23] and tocilizumab in February 2021 [24] could be reasons for the increasing ICU survival in subsequent COVID-19 waves [25]. Indeed, the more pronounced decrease in C-reactive protein over the ICU stay and the concomitant increase in leucocyte and specifically neutrophil counts at later stages of the pandemic may seem to reflect the systematic initiation of corticosteroids, possibly conjointly employed with tocilizumab [4, 26].

The younger age of patients admitted to the ICU could be the primary factor accounting for the prolongation of periods between symptom onset and hospital admission as well as hospital admission and ICU admission. Younger patients, presenting with fewer comorbidities, have greater pulmonary reserves and can compensate lower respiratory tract infections more effectively than elders [27, 28]. Additionally, increasing experience in the treatment of acute hypoxemic respiratory failure due to COVID-19 in hospital wards including more advanced non-invasive respiratory support strategies and the progressive use of awake prone positioning might have postponed or completely avoided ICU admission [8, 29, 30]. This time lag could also explain the more pronounced hypoxemia and higher dead space at ICU admission in the later months of the pandemic possibly induced by patient self-inflicted lung injury (P-SILI) and contrasting with the lower overall severity scores [12, 31]. Furthermore, as previously mentioned, early initiation of dexamethasone and remdesivir, but also the increasing use of intermediate and therapeutic anticoagulation after the first wave might be responsible for the delayed ICU admission [4, 5, 23]. The widespread implementation of intermediate and therapeutic anticoagulation strategies already in wards and intermediate care units at later stages of the pandemic could also explain the decrease in D-dimer levels at ICU admission. On the other hand, the lack of change in D-dimer dynamics over the first 5 days of the ICU stay could reflect the demonstrated lack of efficacy of these therapies when patients have already reached the ICU setting [32].

Similar to other reports, the use of invasive mechanical ventilation in the ICU has declined over the course of the pandemic, this seems to be primarily the effect of the increased use of high-flow oxygen therapy and non-invasive ventilation strategies, synergistically used with awake prone position, albeit the younger age and reduced organ dysfunction could also be plausible reasons [6,7,8]. However, the use of ECMO as salvage therapy in invasively mechanically ventilated patients substantially increased during the pandemic. Whether the latter reflects increased lung damage in ultimately intubated patients [12] or less strict regulations for the initiation of ECMO as a consequence of the patient’s younger age [33], remains unknown. The decreasing length of stay and increasing survival in ICUs worldwide, albeit possibly confounded by age and lower disease severity, are, however, reassuring and evidence of the immense advances made in the care of critically ill COVID-19 patients.

Our study has many strengths. Its multicentre design including 90 centres in 22 countries make the observations generalizable to a wide international critically ill COVID-19 population. Its prospective design allows for a near real-time analysis of the characteristics of critically ill COVID-19 patients throughout the pandemic. This allows insights not only into the epidemiological changes of the COVID-19 pandemic, but also capturing effects of factors that might affect the course of the pandemic, such as public health policies, the prevalence of novel virus variants, the introduction of new treatments and the increasing rates of vaccination. Moreover, using a unique statistical approach (Δlate-early) this study was able to capture subtle changes in the dynamics of disease course during the first days after ICU admission.

The present analysis, however, also has important limitations. First, the high intra- and inter-country heterogeneity regarding socio-economic differences (Additional file 1: e-Figure 15), delivery of care, ICU admission regulations, staff-to-patient ratios and temporal incidence of critically ill patients can limit the interpretability of the data. Additionally, temporal changes in ICU admission policies and an increasing use of advanced respiratory support and specialized medication in non-ICU hospital wards, including high-flow oxygenation and non-invasive mechanical ventilation, could bias the epidemiology of patients admitted to the ICU. We, however, employed centre-within-country nesting to minimize the bias induced by these heterogeneous effects. Second, although standard clinical reporting form and codebook were available, a substantial fraction of fields reported missing data, possibly limiting the interpretation of the results. Nevertheless, by only considering variables with a missing rate below 70% and through rigorous monitoring of data quality the effect of missingness could be reasonably mitigated. Finally, some centres that included patients during the first wave did not recruit patients during subsequent waves. However, the larger most representative centres did continuously include all their patients throughout the 19 months of the pandemic. This, in combination with within centre random effects, allowed to reduce the residual bias originating from inconsistent recruitment strategies.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study confirms the continuous evolution of the COVID-19 pandemic and provides important insights into the epidemiological dynamics of critically ill patients admitted to ICUs worldwide, as well as to their clinical management. During subsequent waves of the pandemic, patients admitted to the ICU were younger, had less comorbidities, were less severely ill, had an increased survival and a shorter length of stay. Concomitantly, a higher proportion of patients were treated with corticosteroids as well as tocilizumab and less patients were mechanically ventilated. Close monitoring of the changing characteristics and disease course of critically ill COVID-19 patients is essential to continuously guide public health policies, prospectively tailor new therapeutical approaches and promote evidence-based management during this health crisis.

Availability of data and materials

Any intensive care unit or other centre treating critically ill COVID-19 patients is invited to join the RISC-19-ICU registry at https://www.risc-19-icu.net. Analyses on the full data set may be requested by all collaborating centres after approval of the study protocol by the registry board.

Code availability

Code for registry-specific data transformation and statistical analysis has been made available for collaborative development on the GitHub and Zenodo repositories. The registry protocol and data dictionary may be found at https://www.risc-19-icu.net.

References

Chan JF-W, Yuan S, Kok K-H, To KK-W, Chu H, Yang J, Xing F, Liu J, Yip CC-Y, Poon RW-S, et al. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):514–23.

Wendel Garcia PD, Fumeaux T, Guerci P, Heuberger DM, Montomoli J, Roche-Campo F, Schuepbach RA, Hilty MP, Alfaro Farias M, Margarit A, et al. Prognostic factors associated with mortality risk and disease progression in 639 critically ill patients with COVID-19 in Europe: initial report of the international RISC-19-ICU prospective observational cohort. EClinicalMedicine. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-021-03580-y.

Zanella A, Florio G, Antonelli M, Bellani G, Berselli A, Bove T, Cabrini L, Carlesso E, Castelli GP, Cecconi M, et al. Time course of risk factors associated with mortality of 1260 critically ill patients with COVID-19 admitted to 24 Italian intensive care units. Intensive Care Med. 2021;47(9):995–1008.

Group TRC. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;384(8):693–704.

The ATTACC A-a, and REMAP-CAP Investigators. Therapeutic anticoagulation with heparin in noncritically ill patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(9):790–802.

Schmidt M, Hajage D, Demoule A, Pham T, Combes A, Dres M, Lebbah S, Kimmoun A, Mercat A, Beduneau G, et al. Clinical characteristics and day-90 outcomes of 4244 critically ill adults with COVID-19: a prospective cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2021;47(1):60–73.

Doidge JC, Gould DW, Ferrando-Vivas P, Mouncey PR, Thomas K, Shankar-Hari M, Harrison DA, Rowan KM. Trends in Intensive Care for Patients with COVID-19 in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;203(5):565–74.

Kurtz P, Bastos LSL, Dantas LF, Zampieri FG, Soares M, Hamacher S, Salluh JIF, Bozza FA. Evolving changes in mortality of 13,301 critically ill adult patients with COVID-19 over 8 months. Intensive Care Med. 2021;47(5):538–48.

Villani L, McKee M, Cascini F, Ricciardi W, Boccia S. Comparison of deaths rates for COVID-19 across Europe during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Public Health. 2020. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.620416.

Bauer J, Brüggmann D, Klingelhöfer D, Maier W, Schwettmann L, Weiss DJ, Groneberg DA. Access to intensive care in 14 European countries: a spatial analysis of intensive care need and capacity in the light of COVID-19. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(11):2026–34.

Henzi A, Kleger G-R, Hilty MP, Wendel Garcia PD, Ziegel JF. on behalf of R-ICUIfS: probabilistic analysis of COVID-19 patients’ individual length of stay in Swiss intensive care units. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(2): e0247265.

Wendel Garcia PD, Aguirre-Bermeo H, Buehler PK, Alfaro-Farias M, Yuen B, David S, Tschoellitsch T, Wengenmayer T, Korsos A, Fogagnolo A, et al. Implications of early respiratory support strategies on disease progression in critical COVID-19: a matched subanalysis of the prospective RISC-19-ICU cohort. Crit Care. 2021;25(1):175.

Zhao C, Tepekule B, Criscuolo NG, Wendel-Garcia PD, Hilty MP, Risc-Icu Consortium Investigators In S, Fumeaux T, Van Boeckel T. icumonitoring.ch: a platform for short-term forecasting of intensive care unit occupancy during the COVID-19 epidemic in Switzerland. Swiss Med Wkly. 2020;150:w20277.

Hilty MP, Moser A, David S, Wendel Garcia PD, Capaldo G, Keiser S, Fumeaux T, Guerci P, Montomoli J, Van Boeckel TP, et al. Near real-time observation reveals increased prevalence of young patients in the ICU during the emerging third SARS-CoV-2 wave in Switzerland. Swiss Med Wkly. 2021;151: w20553.

Sinha P, Calfee CS, Beitler JR, Soni N, Ho K, Matthay MA, Kallet RH. Physiologic analysis and clinical performance of the ventilatory ratio in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;199(3):333–41.

Harrell FE. Regression modeling strategies: with applications to linear models, logistic regression, and survival analysis, vol. 608. Cham: Springer; 2001.

Team RC: R: a language and environment for statistical computing. 2013.

Hernán MA. Causal analyses of existing databases: no power calculations required. J Clin Epidemiol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.08.028.

Dagan N, Barda N, Kepten E, Miron O, Perchik S, Katz MA, Hernán MA, Lipsitch M, Reis B, Balicer RD. BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine in a nationwide mass vaccination setting. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(15):1412–23.

Nivette A, Ribeaud D, Murray A, Steinhoff A, Bechtiger L, Hepp U, Shanahan L, Eisner M. Non-compliance with COVID-19-related public health measures among young adults in Switzerland: insights from a longitudinal cohort study. Soc Sci Med. 2021;268: 113370.

Group TRC. Effect of hydroxychloroquine in hospitalized patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(21):2030–40.

Group RC. Lopinavir-ritonavir in patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 (RECOVERY): a randomised, controlled, open-label, platform trial. Lancet. 2020;396(10259):1345–52.

Beigel JH, Tomashek KM, Dodd LE, Mehta AK, Zingman BS, Kalil AC, Hohmann E, Chu HY, Luetkemeyer A, Kline S, et al. Remdesivir for the treatment of Covid-19—final report. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(19):1813–26.

Investigators TR-C. Interleukin-6 receptor antagonists in critically ill patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(16):1491–502.

Navaratnam AV, Gray WK, Day J, Wendon J, Briggs TWR. Patient factors and temporal trends associated with COVID-19 in-hospital mortality in England: an observational study using administrative data. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9(4):397–406.

Hofmaenner DA, Wendel Garcia PD, Ganter CC, Brugger SD, Buehler PK, David S. What every intensivist should know about Tocilizumab. Crit Care. 2021;25(1):262.

Ewig S, Bauer T, Richter K, Szenscenyi J, Heller G, Strauss R, Welte T. Prediction of in-hospital death from community-acquired pneumonia by varying CRB-age groups. Eur Respir J. 2013;41(4):917.

Roman MA, Rossiter HB, Casaburi R. Exercise, ageing and the lung. Eur Respir J. 2016;48(5):1471.

Grieco DL, Menga LS, Cesarano M, Rosà T, Spadaro S, Bitondo MM, Montomoli J, Falò G, Tonetti T, Cutuli SL, et al. Effect of helmet noninvasive ventilation vs high-flow nasal oxygen on days free of respiratory support in patients with COVID-19 and moderate to severe hypoxemic respiratory failure: the HENIVOT randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2021;325(17):1731–43.

Ehrmann S, Li J, Ibarra-Estrada M, Perez Y, Pavlov I, McNicholas B, Roca O, Mirza S, Vines D, Garcia-Salcido R, et al. Awake prone positioning for COVID-19 acute hypoxaemic respiratory failure: a randomised, controlled, multinational, open-label meta-trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9:1387–95.

Wendel-Garcia PD, Mas A, González-Isern C, Ferrer R, Máñez R, Masclans J-R, Sandoval E, Vera P, Trenado J, Fernández R, et al. Non-invasive oxygenation support in acutely hypoxemic COVID-19 patients admitted to the ICU: a multicenter observational retrospective study. Crit Care. 2022;26(1):37.

ATTACC. Therapeutic anticoagulation with heparin in critically ill patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(9):777–89.

Riera J, Roncon-Albuquerque R, Fuset MP, Alcántara S, Blanco-Schweizer P, Riera J, Bonilla C, Roncon-Albuquerque R, Vaz A, Fuset MP, et al. Increased mortality in patients with COVID-19 receiving extracorporeal respiratory support during the second wave of the pandemic. Intensive Care Med. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-021-06517-9.

RISC-19-ICU Investigators

The RISC-19-ICU Investigators are enumerated in a separate list and should be indexed in PubMed. Registry Board: Matthias P. Hilty†, Pedro D. Wendel Garcia†, Reto A. Schuepbach, Jonathan Montomoli, Philippe Guerci, Thierry Fumeaux. †initiated the registry and designed the e-CRF. Local Center Collaborators: Listed in alphabetical order of countries and cities. Algeria: Centre Hospitalo Universitaire - Saadna Mohamed Abdnour, Setif: Souad Bouaoud, Amel Ouyahia, Meriem Abdoun, Mounira Rais. Andorra: Hospital Nostra Senyora de Meritxell, Escaldes-Engordany: Mario Alfaro-Farias, Gerardo Vizmanos-Lamotte, Angel Caballero. Austria: Kepler University Hospital GmbH and Johannes Kepler University, Linz: Thomas Tschoellitsch, Jens Meier. Ecuador: Hospital Vicente Corral Moscoso, Cuenca: Hernán Aguirre-Bermeo, Pedro Arias-Sanchez, Janina Apolo, Luis A. Martinez, Hugo Tirapé-Castro. Egypt: Aswan University Hospital, Aswan: Islam Galal. Mansoura University Hospitals, Mansoura: Samar Tharwat. Zagazig University Hospitals, Zagazig: Ibrahim Abdehaleem. France: Clinique Louis Pasteur, Essey-lès-Nancy: Geoffrey Jurkolow. University Hospital of Nancy, Nancy: Philippe Guerci, Emmanuel Novy, Marie-Reine Losser. Germany: Medical Center University of Freiburg, Freiburg: Tobias Wengenmayer, Viviane Zotzmann. Medical School Hannover, Hannover: Sascha David, Klaus Stahl, Benjamin Seeliger, Tobias Welte. Greece: St. Paul General Hospital of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki: Theodoros Aslanidis. Hungary: University of Szeged, Szeged: Anita Korsos. Iraq: Al-Hussaien Teaching Hospital, Samawa: Luqman Abdulkhudhur Ahmed. Al-Nassiryah Teaching Hospital, Thi Qar: Hashim Talib Hashim. Iran: Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz: Reza Nikandish. Italy: Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria Ospedali Riuniti di Ancona, Ancona: Andrea Carsetti, Erika Casarotta, Paolo Giaccaglia. Policlinico San Marco - Gruppo Ospedaliero San Donato, Bergamo: Emanuele Rezoagli, Matteo Giacomini, Aurora Magliocca. Ospedale Bufalini, Cesena: Giuliano Bolondi. Azienda Unità Sanitaria Locale della Romagna, Faenza: Antonella Potalivo. Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Ferrara, Cona: Alberto Fogagnolo. IRCCS Centro Cardiologico Monzino, Milan: Luca Salvi. ASST Fatebenefratelli Sacco - “Luigi Sacco” Hospital, Milan: Maddalena A. Wu, Chiara Cogliati, Riccardo Colombo, Emanuele Catena. Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria di Modena, Modena: Fabrizio Turrini, Maria S. Simonini, Silvia Fabbri. Ospedale Infermi, Rimini: Jonathan Montomoli, Emiliano Gamberini, Gianfilippo Gangitano, Maria M. Bitondo, Francesca Maciopinto, Enrico de Camillis, Marta Venturi. Fondazione Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli IRCCS, Rome: Maria Grazia Bocci, Massimo Antonelli. Libya: Ghadames General Hospital, Ghadames: Arowa Alansari. Almwasfat Clinic, Tripoli: Abdurraouf Abusalama. Alzintan Hospital, Tripoli: Osama Omar. Tripoli Central Hospital, Tripoli: Muhannud Binnawara. Tripoli Medical Center, Tripoli: Hind Alameen. University of Tripoli, Tripoli: Muhammed Elhadi. Sorman Teaching Hospital, Sorman: Abdulmueti Alhadi. Tobruk Medical Centre, Tobruk: Ahmed Arhaym. Netherlands: Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam: Diederik Gommers, Can Ince. Palestine: Nasser Medical Complex, Gaza: Mustafa Jayyab. Al-Ahli Hospital, Hebron: Mohammed Alsharif. Spain: Complejo Hospitalario Universitario A Coruña, A Coruña: Raquel Rodríguez-García, Jorge Gámez-Zapata, Xiana Taboada-Fraga. Hospital Clínic de Barcelona, Barcelona: Pedro Castro, Javier Fernandez, Enric Reverter. Hospital General San Jorge, Huesca: Arantxa Lander-Azcona, Jesús Escós-Orta. Hospital Universitario de Torrejon, Madrid: Maria C. Martín-Delgado, Angela Algaba-Calderon. Hospital Verge de la Cinta de Tortosa, Tarragona: Ferran Roche-Campo, Diego Franch-Llasat, Pablo Concha, Esther Sauras-Colón. Hospital Clínico Universitario Lozano Blesa, Zaragoza: Herminia Lozano-Gómez, Begoña Zalba-Etayo, Maria P. Montes. Switzerland: Kantonsspital Aarau, Aarau: Marc P. Michot, Alexander Klarer, Rolf Ensner. Zuger Kantonsspital AG, Baar: Peter Schott, Severin Urech. Universitaetsspital Basel, Basel: Martin Siegemund, Nuria Zellweger, Caroline E. Gebhard, Alexa Hollinger. St. Claraspital, Basel: Lukas Merki, Adriana Lambert. Spitalzentrum Biel, Biel: Marcus Laube University Hospital Bern, Bern: Marie M. Jeitziner, Andre Moser, Yok-Ai Que, Stephan M. Jakob. Lindenhofspital, Bern: Jan Wiegand. Spital Buelach, Buelach: Bernd Yuen, Barbara Lienhardt-Nobbe, Andrea Westphalen. Regionalspital Emmental AG, Burgdorf: Petra Salomon. Kantonsspital Graubuenden, Chur: Frank Hillgaertner, Marianne Sieber. Spital Thurgau, Frauenfeld: Alexander Dullenkopf, Giulio Barana. Hopital cantonal de Fribourg, Fribourg: Hatem Ksouri, Govind O. Sridharan. University Hospitals of Geneva, Geneva: Sara Cereghetti, Filippo Boroli, Jerome Pugin, Serge Grazioli. Spital Grabs, Grabs: Christian Bürkle. See-Spital Horgen & Kilchberg, Horgen: Julien Marrel, Mirko Brenni. Hirslanden Clinique Cecil, Lausanne: Isabelle Fleisch. University Hospital Lausanne, Lausanne: Marie-Helene Perez, Anne-Sylvie Ramelet. Kantonsspital Baselland, Liestal: Anja Baltussen Weber, Peter Gerecke, Andreas Christ.Clinica Luganese Moncucco, Lugano: Samuele Ceruti, Andrea Glotta, Maira Biggiogero. Spital Maennedorf AG, Maennedorf: Katharina Marquardt. Spital Thurgau, Muensterlingen: Tobias Hübner, Thomas Neff. Schweizer Paraplegikerzentrum Nottwil, Nottwil: Hermann Redecker. Groupement Hospitalier de l'Ouest Lémanique - Hôpital de Nyon, Nyon: Thierry Fumeaux, Mallory Moret-Bochatay, Marco Betello. Spitalzentrum Oberwallis, Visp: Friederike Meyer zu Bentrup. Kantonsspital Olten, Olten: Michael Studhalter. Spital Oberengadin, Samedan: Michael Stephan. Kantonsspital Schaffhausen, Schaffhausen: Nadine Gehring. Spital Schwyz, Schwyz: Daniela Selz. Kantonsspital St. Gallen, St. Gallen: Gian-Reto Kleger, Claudia Schrag, Urs Pietsch, Miodrag Filipovic. Kantonsspital Nidwalden, Stans: Anette Ristic. Spital Simmental-Thun-Saanenland AG, Thun: Antje Heise. Établissements hospitaliers du Nord vaudois, Yverdon-les-Bains: Marilene Franchitti Laurent, Jean-Christophe Laurent. Hirslanden Klinik Im Park, Zurich: Tomislav Gaspert. Klinik Hirslanden, Zurich: Christoph Haberthuer. Stadtspital Triemli, Zurich: Patricia Fodor, Pascal Locher. University Hospital Zurich, Zurich: Pedro D. Wendel Garcia, Matthias P. Hilty, Reto Schuepbach, Stefanie Keiser, Dorothea Heuberger, Jan Bartussek, Philipp Bühler, Silvio Brugger, Eva-Maria Kleinert, Kim-Jana Fehlbier. Syria: Aleppo University Hospital, Aleppo: Aghyad Danial. Hamer National Hospital, Hama: Maher Almousa. National Hospital of Lattakia, Lattakia: Yazan Abdulbaki. Turkey: Ondokuz Mayis University Hospital, Samsun: Kamil Sannah. Samsun Training and Research Hospital, Samsun: Elif Colak. UK: Royal Brompton and Harefield NHS, London: Nandor Marczin. Yemen: Al-Yemen Alseed Hospital, Sanaa: Saba Al-Ameri.

Funding

The RISC-19-ICU registry is supported by the Swiss Society of Intensive Care Medicine and funded by internal resources of the Institute of Intensive Care Medicine, of the University Hospital Zurich and by unrestricted grants from CytoSorbents Europe GmbH (Berlin, Germany) and Union Bancaire Privée (Zurich, Switzerland). The study sponsors were not involved in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data; preparation, review or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

The order of appearance in this list reflects the order of appearance in the author list. PAWG, AM, SMJ, Y-AQ and MPH designed and conceived the present analysis. PAWG, AM, M-MJ, HA-B, PA-S, JA, FR-C, DF-L, G-RK, CS, UP, MF, SD, KS, SB, AO, PF, PL, MS, NZ, SC, PS, GG, MAW, MA-F, GV-L, HK, NG, ER, FT, HL-G, AC, RR-G, BY, ABW, PC, JOE-O, AD, MCM-D, TA, M-HP, FH, SC, MFL, JM, RC, ML, AF, MS, TW, EG, CB, PKB, SK, ME, JM, PG, TF, RAS, SMJ, Y-AQ and MPH acquired, analysed and interpreted the data. PAWG, AM and MPH performed statistical analysis. PAWG, AM, SMJ, Y-AQ and MPH drafted the manuscript. PAWG, RASS and MPH secured funding. PAWG and MPH supervised the study. All authors read, critically revised and approved the final manuscript. All authors had full access to the full data in the study and accept responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The registry (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04357275) has been endorsed by the Swiss Society of Intensive Care Medicine and was exempt from the need for additional ethics approval and patient informed consent by the ethics committee of the University of Zurich (KEK 2020-00322). The study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki; the Guidelines on Good Clinical Practice issued by the European Medicines Agency, the Swiss law and Swiss regulatory authority requirements as well as the regulatory authority requirements in each participating country. Written informed consent for participation from the patient or in case of death or disability, from the next of kin or legal representative, was sought for every patient included into this registry if required by the regulatory authority responsible for the respective participating centre.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent for publication from the patient or in case of death or disability, from the next of kin or legal representative, was sought for every patient included into this registry if required by the regulatory authority responsible for the respective participating centre.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Online Supplementary Material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Wendel-Garcia, P.D., Moser, A., Jeitziner, MM. et al. Dynamics of disease characteristics and clinical management of critically ill COVID-19 patients over the time course of the pandemic: an analysis of the prospective, international, multicentre RISC-19-ICU registry. Crit Care 26, 199 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-022-04065-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-022-04065-2