Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate differences in the characteristics and outcomes of intensive care unit (ICU) patients over time.

Methods

We reviewed all epidemiological data, including comorbidities, types and severity of organ failure, interventions, lengths of stay and outcome, for patients from the Sepsis Occurrence in Acutely ill Patients (SOAP) study, an observational study conducted in European intensive care units in 2002, and the Intensive Care Over Nations (ICON) audit, a survey of intensive care unit patients conducted in 2012.

Results

We compared the 3147 patients from the SOAP study with the 4852 patients from the ICON audit admitted to intensive care units in the same countries as those in the SOAP study. The ICON patients were older (62.5 ± 17.0 vs. 60.6 ± 17.4 years) and had higher severity scores than the SOAP patients. The proportion of patients with sepsis at any time during the intensive care unit stay was slightly higher in the ICON study (31.9 vs. 29.6%, p = 0.03). In multilevel analysis, the adjusted odds of ICU mortality were significantly lower for ICON patients than for SOAP patients, particularly in patients with sepsis [OR 0.45 (0.35–0.59), p < 0.001].

Conclusions

Over the 10-year period between 2002 and 2012, the proportion of patients with sepsis admitted to European ICUs remained relatively stable, but the severity of disease increased. In multilevel analysis, the odds of ICU mortality were lower in our 2012 cohort compared to our 2002 cohort, particularly in patients with sepsis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

This comparison of two databases created 10 years apart shows that ICU populations in Europe have changed over time. ICU patient are now slightly older and more severely ill. The number of patients with shock has increased as has the use of renal replacement therapies, whereas the proportion of patients receiving mechanical ventilation has decreased. ICU length of stay has remained unchanged and ICU mortality rates may have decreased. |

Introduction

Intensive care medicine is a relatively new specialty, but one that has evolved considerably over its short existence. Over the last 15 years or so, improved understanding of underlying disease pathogenesis and the role of “iatrogenic” complications has led to key changes in management and process of care in intensive care unit (ICU) patients, including use of lower tidal volume ventilation, more restrictive blood transfusion practice, and less sedation, which may have helped reduce mortality rates. Conversely, the aging world population with increased comorbidity, increased use of chemotherapy and immunosuppression, and medical advances that enable an increasing number of chronically ill patients to survive into old age, may favor admission of a sicker cohort of patients to the ICU and thus result in increased mortality rates.

Sepsis remains a leading cause of death worldwide among critically ill patients [1]. Although several recent studies have reported a substantial increase in the number of cases of sepsis per year, with a decrease in mortality of these patients [1, 2], this may largely be a reporting phenomenon associated with more complete capture of less ill patients [3, 4].

To assess the changing epidemiology of ICU patients, and of sepsis in particular, we compared two large multinational observational studies conducted on ICU patients exactly 10 years apart, the Sepsis Occurrence in Acutely ill Patients (SOAP) study conducted in 2002 [5] and the larger worldwide Intensive Care Over Nations (ICON) audit conducted in 2012 [6]. The data collected for the two studies were almost identical and analysis was conducted in the same center, facilitating comparisons and reducing the risk of bias. We hypothesized that patients in the current ICON era would be sicker but have lower mortality rates than patients in the SOAP study.

Methods

The SOAP study was conducted in 24 European countries and included 3147 patients [5]. The ICON audit included 10,069 patients from 82 countries worldwide [6]. For the purposes of this comparison, we considered only the patients from ICON who were admitted to the same 24 European countries as in the SOAP study (e-Table 1, e-Appendix). For both studies, recruitment for participation was by open invitation, through national scientific societies, national and international meetings, and individual contacts. Participation was entirely voluntary, with no financial incentive. Institutional review board approval for both studies was obtained by the participating institutions according to local ethical regulations.

Participating ICUs (see e-Appendix) were asked to prospectively collect data on all adult patients admitted between May 1 and 15, 2002 for the SOAP study and between May 8 and 18, 2012 for the ICON audit. In both studies, patients who stayed in the ICU for < 24 h for routine postoperative surveillance were not considered. Re-admissions of previously included patients were also not included. Data were collected daily during the ICU stay for a maximum of 28 days. Patients were followed up for outcome data until death, hospital discharge or for 60 days.

Data were collected by the investigators using preprinted (for SOAP) and electronic (for ICON) case report forms. Data collection on admission included demographic data and comorbid diseases as well as source and reason for admission. Clinical and laboratory data for SAPS II [7] scores were reported as the worst values within 24 h after admission. The presence of microbiologically confirmed and clinically suspected infections was reported daily as were the antibiotics administered. A daily evaluation of organ function was performed using the sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) score [8].

Definitions

Sepsis was defined as the presence of infection with the concomitant occurrence of at least one organ failure (defined as a SOFA score > 2 for the organ in question) in ICON, equivalent to the definition of “severe sepsis” used in SOAP. For the purposes of this comparison, we used this ICON definition of sepsis, recently supported by international consensus [9].

Data management and quality control

Detailed instructions explaining the aim of the study, instructions for data collection, and definitions were available through a secured website for all participants before starting data collection and throughout the study period. Additional queries were answered on a per case basis by the coordinating center during data collection. Data were further reviewed by the coordinating center for plausibility and availability of the outcome parameter, and any doubts were clarified with the center in question. There was no on-site monitoring. Missing data represented < 6% of the data collected for SOAP and 6.1% of the ICON data.

Statistical analysis

All data were processed and analyzed in the Department of Intensive Care of Erasme Hospital, University of Brussels, in collaboration with Jena University Hospital, Jena, Germany. Data were analyzed using IBM® SPSS® Statistics software, v.24 for Windows (IBM, Somers, NY, USA).

Data are summarized using means with standard deviation, medians and interquartile ranges, or numbers and percentages. Difference testing between groups was performed using Student’s t test, Mann–Whitney test, Chi square test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used, and histograms and quantile–quantile plots were examined to verify whether there were significant deviations from the normality assumption of continuous variables.

To identify the effect of being in the SOAP or ICON study on ICU mortality, and because of the hierarchical structure of the data, we performed a multivariable analysis using a multilevel binary logistic model with three levels: patient (level 1), admitted to a hospital (level 2), within a country (level 3). The dependent variable was ICU mortality. The explanatory variables considered in the model were age, sex, SAPS II score without age component, type of admission, source of admission, treatment with mechanical ventilation or renal replacement therapy (RRT), presence of sepsis, comorbidities and the study to which the patient belonged, i.e., SOAP or ICON.

For parameter testing, the likelihood-ratio test was used. Colinearity between variables was checked by inspection of the correlation between them, looking at the correlation matrix of the estimated parameters. The interaction between explanatory variables was also tested. Three models were constructed: the first model, an unconditional model with no exposure factors, was used to discern the amount of variance that existed between hospital and country levels; the second model (the unadjusted model) contained the study to which the patient belonged, presence of sepsis and their interaction; and the third model (the adjusted model) was extended to include the other patient characteristics. The results of the fixed effects (measures of association) are given as odds ratios (ORs) with their 95% CIs. A second order penalized quasi-likelihood (PQL) estimation method was used, because this method approximates well compared to other methods [10]. The statistical significance of covariates was calculated using the Wald test. No statistical adjustments were used for multiple testing. All reported p values are two-sided and a p value of less than 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

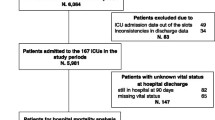

We compared the 3147 patients from the SOAP study with the 4852 patients from the ICON audit who were admitted to ICUs in the same countries as the patients in the SOAP study. The number of centers and number of patients in each country is shown in e-Table 1, the main differences being that a smaller proportion of patients were included from Belgium and France in ICON than in SOAP and a larger proportion from the UK and Spain.

The characteristics of the two patient populations are shown in Tables 1 and 2. ICON patients were older (62.5 ± 17.0 vs. 60.6 ± 17.4 years, p < 0.001) than SOAP patients and more likely to have co-morbid chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. They were more likely to be receiving chemotherapy on admission and less likely to be receiving corticosteroids. ICON patients were more likely to have circulatory shock, respiratory failure and/or liver failure on admission than SOAP patients. They had higher SAPS II scores (41.9 ± 18.2 vs. 36.5 + 17.1) on admission, higher SOFA scores on admission (6.3 ± 4.3 vs. 5.1 ± 3.8) and higher max SOFA scores during the ICU stay (7.8 ± 4.8 vs. 6.6 ± 4.4) than the SOAP patients (all p < 0.001).

ICON patients were less likely to receive invasive mechanical ventilation during their ICU stay (59.3 vs. 64.3%, p < 0.001) but more likely to be treated with renal replacement therapy (RRT; 12.7 vs. 9.7%, p < 0.001). There was a small increase in the proportion of patients with sepsis at any time during the ICU stay between the two studies (29.6% in SOAP vs. 31.9% in ICON, p = 0.03). Gram-negative pathogens were more frequently isolated (66.3 vs. 60.2%, p = 0.01) and fungi less frequently isolated (14.8 vs. 20.7%, p < 0.001) in infected ICON patients than in infected SOAP patients (e-Table 2).

The ICU lengths of stay were not significantly different in the two studies, but the overall ICU mortality rate was slightly lower in ICON than in SOAP (16.8 vs. 18.5%, p = 0.05). Hospital (24.1% in SOAP vs. 23.9 in ICON, p = 0.83) and 60-day (23.4% in SOAP vs. 23.7 in ICON, p = 0.75) mortality rates were not different between the studies. The improvement in ICU survival was particularly notable in patients with sepsis, shock or liver failure on admission or during the ICU stay, and those with renal failure during the ICU admission (Table 2). ICU mortality rates were significantly lower in ICON for all degrees of organ failure on admission (Fig. 1) and for all numbers of failing organs during the ICU admission (Table 2). Similar patterns in ICU mortality rates were identified in patients with and without sepsis (e-Tables 3 and 4, e-Figure 1).

In multilevel analysis, the adjusted odds of ICU mortality were significantly lower for ICON patients than for SOAP patients, both with and without sepsis (Table 3). Interestingly, the reduced odds were greater for patients with sepsis than for those without in both non-adjusted (p = 0.016) and adjusted (p = 0.006) analyses. The unconditional model indicated significant between-country (var 0.21, p = 0.015) and between-hospital (var 0.23, p < 0.001) variations in the individual risk of in-ICU death (Table 3). After controlling for patient factors, the differences across hospitals remained statistically significant (var 0.29, p < 0.0001); in contrast, the differences across countries disappeared after adjustment (var 0.06, p = 0.23).

Discussion

This comparison of two databases created 10 years apart shows some important epidemiological differences in ICU populations in Europe over time. The number of patients with shock has increased as has the use of renal replacement therapies, whereas the proportion of patients receiving mechanical ventilation has decreased. Although ICU patient populations are slightly older and more severely ill, ICU survival rates have improved even after adjustment for multiple potential confounders.

The proportion of patients receiving invasive mechanical ventilation decreased over the 10-year period. Indeed, although the proportion of patients with respiratory failure at ICU admission was greater in ICON than in SOAP, the proportion during the ICU stay was lower. Moreover, we can speculate that more patients with respiratory failure are now managed using non-invasive mechanical ventilation [11] and/or high-flow nasal cannula oxygen [12]. We chose not to record data on non-invasive ventilation as it is difficult to evaluate over 24-h periods. It is also possible that mechanical ventilation was more frequently withheld in the ICON cohort; however, the decreased mortality rate in a sicker cohort of patients argues against this possibility. In contrast to the reduced use of mechanical ventilation, there was an increased use of RRT in the ICON population, as expected with the larger proportion of patients with renal failure during the ICU stay. Sakhuja et al. also recently reported an increased incidence of acute kidney injury requiring dialysis in patients with sepsis between 2000 and 2009 [13].

A number of studies have reported that the incidence of sepsis has increased dramatically over time. However, as suggested by Rhee et al. [14], this may be largely a reporting phenomenon associated with financial reimbursement or increasing awareness of and familiarity with sepsis-related definitions and coding among medical staff [15,16,17]. Using clinical data alone, these same authors recently reported no increase in sepsis incidence between 2009 and 2014 in almost 8,000,000 admissions to US hospitals, although again incidence increased when sepsis was defined using ICD codes [18]. Our study also suggests that the rate of sepsis (as defined using the criteria of infection associated with organ dysfunction as in the most recent guidelines [9]) has remained relatively stable over the 10-year period. Martin et al. reported an increase in the severity of illness of patients with sepsis across US hospitals over a 22-year period, but a decrease in hospital mortality from 27.8% in 1979–1984 to 17.9% in 1995–2000 [19]. Also in the US, Kumar et al. reported increasing severity of illness, as assessed by the mean number of organ system failures during the ICU stay, during the period 2000–2007, but decreasing mortality rates from 39 to 27% [20]. And Stoller et al. made similar findings during the period 2008–2012 [21]. In Spain, Bouza et al. reported a decrease in case fatality rates from 45 to 40% between 2006 and 2011, despite increasing disease severity [22], and Kaukonen et al. [2] reported a decrease in mortality from 2000 to 2012 for patients with severe sepsis that persisted when adjusted for severity of illness. The decrease in mortality over time, particularly among patients with sepsis, parallel to the increase in disease severity, is an interesting phenomenon that has been reported previously [19,20,22], and suggests that progress has been made in the field of intensive care medicine. Indeed, multiple aspects of ICU patient management have changed over the last decade or so, including, among others, more widespread use of lower tidal volume ventilation [23], more restrictive blood transfusion practice [24], reduced sedative use [25] and earlier mobilization, and more rapid appropriate intervention in patients with sepsis [26], some of which have been associated with improved outcomes. Of note, in-hospital and 60-day mortality rates were not significantly different in our two cohorts. Our data do not enable us to determine the reasons for this observation, although it is interesting to speculate that ICU management may have improved more than post-ICU care.

The strengths of our study are the comparison of two large multicenter registries conducted 10 years apart in the same month of the year, and which prospectively included almost identical variables, analyzed in the same center. But our study also has important limitations. First, although data collection was prospective, our study was observational in nature and the analysis retrospective; we therefore cannot discount that unmeasured factors may have confounded our results. Moreover, because of multiple comparisons, an inflated type 1 error may be possible. In addition, although we clearly demonstrate improved survival of critically ill patients over time, notwithstanding the increased severity of illness, we can only speculate on the mechanism of these improved outcomes. Indeed, the observed increased severity of illness may in part be related to changes in ICU admitting practices or in improved capabilities to care for patients in non-ICU settings. These are important areas of future research. Second, we do not have any information about end-of-life decisions or on outcomes after 60 days. We are also unable to comment on differences in the quality of life of the survivors. Return to reasonable physical, mental and cognitive functionality is an important aspect of patient-centered outcomes. Third, although we included centers from the same countries, we were unable to perform a center-by-center comparison. Over time, hospital names and networks have changed, making a direct comparison impractical. Moreover, we had no data to assess how representative the participating hospitals were of their country. Finally, the SOAP study included patients over a longer period of time (15 days) than the ICON study (11 days). However, this is unlikely to have influenced the results.

Despite these limitations, the present observations show that ICU patients were sicker in our 2012 cohort than in our 2002 cohort. Multilevel analysis showed that survival was improved in the later cohort, especially for patients with sepsis. These results are encouraging and suggest that progress has been made in the field of intensive care medicine over just a 10-year period.

References

Kadri SS, Rhee C, Strich JR, Morales MK, Hohmann S, Menchaca J, Suffredini AF, Danner RL, Klompas M (2016) Estimating ten-year trends in septic shock incidence and mortality in United States academic medical centers using clinical data. Chest 151:278–285

Kaukonen KM, Bailey M, Suzuki S, Pilcher D, Bellomo R (2014) Mortality related to severe sepsis and septic shock among critically ill patients in Australia and New Zealand, 2000–2012. JAMA 311:1308–1316

Rhee C, Gohil S, Klompas M (2014) Regulatory mandates for sepsis care-reasons for caution. N Engl J Med 370:1673–1676

Vincent JL, Mira JP, Antonelli M (2016) Sepsis: older and newer concepts. Lancet Respir Med 4:237–240

Vincent JL, Sakr Y, Sprung CL, Ranieri VM, Reinhart K, Gerlach H, Moreno R, Carlet J, Le Gall JR et al (2006) Sepsis in European intensive care units: results of the SOAP study. Crit Care Med 34:344–353

Vincent JL, Marshall JC, Namendys-Silva SA, Francois B, Martin-Loeches I, Lipman J, Reinhart K, Antonelli M, Pickkers P et al (2014) Assessment of the worldwide burden of critical illness: the Intensive Care Over Nations (ICON) audit. Lancet Respir Med 2:380–386

Le Gall JR, Lemeshow S, Saulnier F (1993) A new simplified acute physiology score (SAPS II) based on a European/North American multicenter study. JAMA 270:2957–2963

Vincent JL, Moreno R, Takala J, Willatts S, de Mendonça A, Bruining H, Reinhart CK, Suter PM, Thijs LG (1996) The SOFA (sepsis-related organ failure assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. Intensive Care Med 22:707–710

Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, Bellomo R, Bernard GR, Chiche JD et al (2016) The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (sepsis-3). JAMA 315:801–810

Goldstein H (2003) Multilevel statistical models. Hodder Arnold, London

Demoule A, Chevret S, Carlucci A, Kouatchet A, Jaber S, Meziani F, Schmidt M, Schnell D, Clergue C et al (2016) Changing use of noninvasive ventilation in critically ill patients: trends over 15 years in francophone countries. Intensive Care Med 42:82–92

Frat JP, Thille AW, Mercat A, Girault C, Ragot S, Perbet S, Prat G, Boulain T, Morawiec E et al (2015) High-flow oxygen through nasal cannula in acute hypoxemic respiratory failure. N Engl J Med 372:2185–2196

Sakhuja A, Kumar G, Gupta S, Mittal T, Taneja A, Nanchal RS (2015) Acute kidney injury requiring dialysis in severe sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 192:951–957

Rhee C, Murphy MV, Li L, Platt R, Klompas M (2015) Comparison of trends in sepsis incidence and coding using administrative claims versus objective clinical data. Clin Infect Dis 60:88–95

Epstein L, Dantes R, Magill S, Fiore A (2016) Varying estimates of sepsis mortality using death certificates and administrative codes—United States, 1999–2014. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 65:342–345

Bouza C, Lopez-Cuadrado T, Amate-Blanco JM (2016) Use of explicit ICD9-CM codes to identify adult severe sepsis: impacts on epidemiological estimates. Crit Care 20:313

Gohil SK, Cao C, Phelan M, Tjoa T, Rhee C, Platt R, Huang SS (2016) Impact of policies on the rise in sepsis incidence, 2000–2010. Clin Infect Dis 62:695–703

Rhee C, Dantes R, Epstein L, Murphy DJ, Seymour CW, Iwashyna TJ, Kadri SS, Angus DC, Danner RL et al (2017) Incidence and trends of sepsis in US hospitals using clinical vs claims data, 2009–2014. JAMA 318:1241–1249

Martin GS, Mannino DM, Eaton S, Moss M (2003) The epidemiology of sepsis in the United States from 1979 through 2000. N Engl J Med 348:1546–1554

Kumar G, Kumar N, Taneja A, Kaleekal T, Tarima S, McGinley E, Jimenez E, Mohan A, Khan RA, Whittle J, Jacobs E, Nanchal R; Milwaukee Initiative in Critical Care Outcomes Research (MICCOR) Group of Investigators (2011) Nationwide trends of severe sepsis in the 21st century (2000–2007). Chest 140:1223–1231

Stoller J, Halpin L, Weis M, Aplin B, Qu W, Georgescu C, Nazzal M (2016) Epidemiology of severe sepsis: 2008–2012. J Crit Care 31:58–62

Bouza C, Lopez-Cuadrado T, Saz-Parkinson Z, Amate-Blanco JM (2014) Epidemiology and recent trends of severe sepsis in Spain: a nationwide population-based analysis (2006–2011). BMC Infect Dis 14:3863

The Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network (2000) Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 342:1301–1308

Hebert PC, Wells G, Blajchman MA, Marshall J, Martin C, Pagliarello G, Tweeddale M, Schweitzer I, Yetisir E (1999) A multicenter, randomized, controlled clinical trial of transfusion requirements in critical care. Transfusion Requirements in Critical Care Investigators, Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. N Engl J Med 340:409–417

Baron R, Binder A, Biniek R, Braune S, Buerkle H, Dall P, Demirakca S, Eckardt R, Eggers V et al (2015) Evidence and consensus based guideline for the management of delirium, analgesia, and sedation in intensive care medicine. Revision 2015 (DAS-Guideline 2015)—short version. Ger Med Sci 13:Doc19

Miller RR III, Dong L, Nelson NC, Brown SM, Kuttler KG, Probst DR, Allen TL, Clemmer TP (2013) Multicenter implementation of a severe sepsis and septic shock treatment bundle. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 188:77–82

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Hassane Njimi PhD for his help with the statistical analyses.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

JLV designed the study, analyzed the data and drafted the article; YS participated in the original ICON and SOAP studies, helped analyze the data and draft the article; JYL, KK, RN, IML, XW, SGS, and PP participated in the original ICON study and revised the article for critical content; RM participated in the original SOAP study and revised the article for critical content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

The members of the ICON and SOAP investigators are listed in the ESM file.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Vincent, JL., Lefrant, JY., Kotfis, K. et al. Comparison of European ICU patients in 2012 (ICON) versus 2002 (SOAP). Intensive Care Med 44, 337–344 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-017-5043-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-017-5043-2