Abstract

Background

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) has been shown to pose considerable clinical and economic burden; however, research quantifying the excess burden attributable to common psychiatric comorbidities of ADHD among pediatric patients is scarce. This study assessed the impact of anxiety and depression on healthcare resource utilization (HRU) and healthcare costs in pediatric patients with ADHD in the United States.

Methods

Patients with ADHD aged 6–17 years were identified in the IQVIA PharMetrics Plus database (10/01/2015-09/30/2021). The index date was the date of initiation of a randomly selected ADHD treatment. Patients with ≥ 1 diagnosis for anxiety and/or depression during both the baseline (6 months pre-index) and study period (12 months post-index) were classified in the ADHD+anxiety/depression cohort; those without diagnoses for anxiety nor depression during both periods were classified in the ADHD-only cohort. Entropy balancing was used to create reweighted cohorts. All-cause HRU and healthcare costs during the study period were compared using regression analyses. Cost analyses were also performed in subgroups by comorbid conditions.

Results

The reweighted ADHD-only cohort (N = 204,723) and ADHD+anxiety/depression cohort (N = 66,231) had similar characteristics (mean age: 11.9 years; 72.8% male; 56.2% had combined inattentive and hyperactive ADHD type). The ADHD+anxiety/depression cohort had higher HRU than the ADHD-only cohort (incidence rate ratios for inpatient admissions: 10.3; emergency room visits: 1.6; outpatient visits: 2.3; specialist visits: 5.3; and psychotherapy visits: 6.1; all p < 0.001). The higher HRU translated to greater all-cause healthcare costs; the mean per-patient-per-year (PPPY) costs in the ADHD-only cohort vs. ADHD+anxiety/depression cohort was $3,988 vs. $8,682 (p < 0.001). All-cause healthcare costs were highest when both comorbidities were present; among patients with ADHD who had only anxiety, only depression, and both anxiety and depression, the mean all-cause healthcare costs were $7,309, $9,901, and $13,785 PPPY, respectively (all p < 0.001).

Conclusions

Comorbid anxiety and depression was associated with significantly increased risk of HRU and higher healthcare costs among pediatric patients with ADHD; the presence of both comorbid conditions resulted in 3.5 times higher costs relative to ADHD alone. These findings underscore the need to co-manage ADHD and psychiatric comorbidities to help mitigate the substantial burden borne by patients and the healthcare system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is one of the most common neurodevelopmental disorders of childhood. According to national surveys in the United States (US), the estimated 12-month prevalence of ADHD was 10.0% among children and 6.5% among adolescents [1,2,3], although estimates in the literature range from 3.4 to 11.1% for children and 3.4–13.6% for adolescents [3,4,5,6,7,8]. Pediatric patients with ADHD are at increased risk of numerous behavioral and psychophysiological problems relative to their non-ADHD counterparts [9,10,11], and the condition is estimated to add $33.2 billion of excess costs to the US society each year [12].

ADHD is a heterogeneous disorder partially exemplified by its extensive psychiatric comorbidities, among which anxiety and depression are common [3, 13]. The presence of psychiatric comorbidities among pediatric patients with ADHD has been shown to exacerbate patient functioning in social and educational domains relative to ADHD alone [14,15,16]. Furthermore, psychiatric comorbidities may confound the management of ADHD by increasing the need for care coordination, use of medications, and time to reach optimal symptom management [17, 18]. Patients with comorbid anxiety and depression in ADHD have also been associated with more treatment changes and increased healthcare costs compared to those with ADHD alone [19].

Although ample evidence has demonstrated that pediatric patients with ADHD have increased healthcare resource utilization (HRU) and expenditures compared to those without ADHD [20,21,22], data on the excess burden imposed by common psychiatric comorbidities are relatively limited. Such knowledge may help inform stakeholders, including patients, parents, teachers, clinicians, and the healthcare system, on tailored strategies for managing ADHD in pediatric patients. The current study aimed to partially address this research gap by quantifying the impact of comorbid anxiety and/or depression on HRU and healthcare costs in pediatric patients with ADHD in the US using a large claims database.

Methods

Data source

Claims data from the IQVIA PharMetrics® Plus (IQVIA) database (10/01/2015-09/30/2021) were used. The database comprises over 190 million unique beneficiaries with a diverse representation of geographic areas, employers, providers, and payers across the US. Information includes inpatient and outpatient diagnoses and procedures, prescription fills, patients’ pharmacy and medical benefits, inpatient stays, and provider details. Additional data elements encompass dates of service, demographic variables, plan type, payer type, and start and stop dates of health plan enrollment. Economic variables include the actual amount paid by health plans to the provider for services rendered. Data analyzed in this study are de-identified and comply with the patient requirements of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA); therefore, no review by an institutional review board nor informed consent was required per Title 45 of CFR, Part 46.101(b)(4) [23].

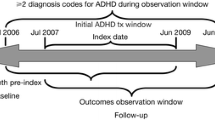

Study design

This study used a retrospective case-cohort design [24]. The index date was defined as the date of initiation of a randomly selected US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved agent for the treatment of ADHD that was newly initiated after the first ADHD diagnosis; this definition allowed capturing of patients at different stages of their ADHD treatment journeys. The baseline period was defined as the 6-month period prior to the index date. The study period was defined as the 12-month period following the index date.

Selection criteria and patient populations

Patients were included in the study if they met the following inclusion criteria: (1) had ≥ 2 ADHD diagnoses (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-10-CM] F90.x) recorded on distinct dates; (2) had ≥ 1 prescription fill for an FDA-approved pharmacological treatment for ADHD on or after the first ADHD diagnosis; (3) had continuous health plan enrollment, including both medical and pharmacy coverage, during the baseline and study periods; and (4) were aged ≥ 6 years at the start of the baseline period and ≤ 17 years at the end of the study period (Supplementary FigureS1).

Eligible patients were classified into two study cohorts: patients with ≥ 1 diagnosis for anxiety and/or depression (as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition [DSM-5] [4]) recorded on a medical claim during both the baseline and study periods were classified into the ADHD+anxiety/depression cohort, and those without diagnoses for anxiety nor depression recorded on a medical claim during the baseline and study periods were classified into the ADHD-only cohort.

For cost analyses, patients in the ADHD+anxiety/depression cohort were further stratified into three subgroups by comorbid conditions: patients with ADHD who, during both the baseline and study periods, only had comorbid anxiety were classified as the ADHD+only anxiety subgroup, those who only had comorbid depression were classified as the ADHD+only depression subgroup, and those with both anxiety and depression were classified as the ADHD+both anxiety and depression subgroup.

Outcome measures

Baseline demographic, clinical, and treatment characteristics were measured based on information recorded in claims data. In particular, psychiatric and physical comorbidities were identified based on ICD-10-CM diagnosis codes recorded on medical claims, and treatments were identified based on pharmacy claims for prescription fills. All-cause HRU and healthcare costs during the study period were assessed. All-cause HRU was reported per-patient-per-year (PPPY) by categories (i.e., inpatient admissions, days with emergency room visits, days with outpatient visits, number of specialist visits [i.e., psychiatrist, neurologist], and psychotherapy visits). All-cause healthcare costs were reported PPPY and included pharmacy and medical costs; the latter comprised of costs related to inpatient, emergency room, and outpatient visits. Costs were assessed from the payer’s perspective (i.e., health plan payment + coordination of benefits, excluding patients’ payment) and adjusted to 2022 US dollars using the medical component of the Consumer Price Index.

Statistical analysis

Entropy balancing was used to create reweighted cohorts [25], with the following baseline characteristics considered: age, sex, region, health plan type, type of ADHD, calendar year of index date, number of agents received on or after ADHD diagnosis and before the index date, time from first observed ADHD diagnosis to first ADHD treatment, and time from first observed diagnosis to index date. Comorbidities related to anxiety and depression were excluded from the entropy balancing as these comorbidities may be a part of the disease burden assessed in this study. Baseline characteristics of the balanced cohorts were summarized using descriptive statistics, with means, medians, and standard deviations reported for continuous variables, and frequency counts and percentages reported for categorical variables. Standardized differences between the cohorts were calculated, with values < 0.10 being considered as well balanced [26].

All-cause HRU was compared between balanced cohorts using weighted negative binomial regression models with a log link and reported as incidence rate ratios along with their 95% confidence intervals and p-values.

All-cause healthcare costs were compared between the balanced cohorts using weighted two-part regression models. In addition, cost analyses were also performed between the ADHD-only cohort and each of the comorbidity subgroups (i.e., ADHD+only anxiety, ADHD+only depression, and ADHD+both anxiety and depression) to assess the excess cost burden attributable to the respective comorbid conditions.

All analyses were performed using SAS Enterprise guide 7.1 and Stata 16.

Results

Sample size

A total of 270,954 patients met the cohort-specific inclusion criteria, including 204,723 patients in the ADHD-only cohort and 66,231 patients in the ADHD+anxiety/depression cohort. Stratified by comorbid conditions, 41,992 patients were included in the ADHD+only anxiety subgroup, 14,054 in the ADHD+only depression subgroup, and 10,185 in the ADHD+both anxiety and depression subgroup (Supplementary FigureS1).

Baseline patient characteristics

Demographic and clinical characteristics were well balanced between the reweighted cohorts (Table 1). Mean patient age was 11.9 years, and the majority were male (72.8%) and had combined inattentive and hyperactive ADHD type (56.2%). The proportion of patients with baseline psychiatric and physical comorbidities were overall higher in the ADHD+anxiety/depression cohort than the ADHD-only cohort. Apart from anxiety and depression, the most prevalent psychiatric comorbidities with a standardized difference of > 0.10 between the cohorts included neurodevelopmental disorders other than ADHD (ADHD-only vs. ADHD+anxiety/depression: 7.8% vs. 20.7%), trauma- and stressor-related disorders (5.7% vs. 15.4%), and disruptive, impulse-control, and conduct disorders (4.7% vs. 15.9%). The most prevalent physical comorbidity with a standardized difference > 0.10 between the cohorts was cardiac arrhythmias (ADHD-only vs. ADHD+anxiety/depression: 1.8% vs. 3.7%).

Although the majority of patients received stimulants as the index treatment in both cohorts, the proportion of patients who received non-stimulants was observed to be numerically higher in the ADHD+anxiety/depression cohort (22.7%) than in the ADHD-only cohort (10.2%); similar trends were observed during the baseline period (Table 1). Furthermore, more patients in the ADHD+anxiety/depression cohort than the ADHD-only cohort received antianxiety agents or antidepressants, or had psychotherapy or specialist visits, during the baseline period.

HRU

During the study period, rates of all-cause HRU were significantly higher in the ADHD+anxiety/depression cohort than in the ADHD-only cohort, with an incidence rate ratio of 10.3 for inpatient admissions, 1.6 for emergency room visits, 2.3 for outpatient visits, 5.3 for specialist visits, and 6.1 for psychotherapy visits (all p < 0.001; Fig. 1).

All-cause HRU during the 12-month study perioda. ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; CI, confidence interval; IR, incidence rate; IRR, incidence rate ratio; PPPY, per-patient-per-year. *Statistically significant at the 0.1% level. aThe ADHD+anxiety/depression cohort comprised patients with ADHD+only anxiety, ADHD+only depression, and ADHD+both anxiety and depression

Healthcare costs

Compared with the ADHD-only cohort, the mean all-cause healthcare costs PPPY were more than twice as high in the ADHD+anxiety/depression cohort ($3,988 vs. $8,682; mean difference: $4,695), driven by differences in both medical and pharmacy costs (all p < 0.001; Fig. 2).

All-cause healthcare costs during the 12-month study perioda. ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; MD, mean difference; PPPY, per-patient-per-year; USD, United States dollar. *Statistically significantly different than the ADHD-only cohort at the 0.1% level. aThe ADHD+anxiety/depression cohort comprised patients with ADHD+only anxiety, ADHD+only depression, and ADHD+both anxiety and depression

Among the subgroups of patients with ADHD, the mean all-cause healthcare costs PPPY were $7,309 among those who had only anxiety, $9,901 among those who had only depression, and $13,785 among those who had both anxiety and depression (all p < 0.001; Fig. 3), translating to 1.8, 2.5, and 3.5 times higher excess healthcare costs compared with those who had ADHD only.

Discussion

The current case-cohort analysis found that relative to pediatric patients with ADHD only, those with ADHD and comorbid anxiety and/or depression were 10 times more likely to be hospitalized and 5–6 times more likely to have a specialist or psychotherapy visit. Furthermore, pediatric patients with ADHD and comorbid anxiety and/or depression incurred more than twice the healthcare costs of those without the comorbidities, with a mean difference of $4,695 PPPY. Notably, the excess healthcare cost further increased among those with both comorbid anxiety and depression, with the total cost being 3.5 times higher than those with ADHD only. Together, these findings underscore the substantial excess HRU and cost burden imposed by comorbid anxiety and depression among pediatric patients with ADHD. The excess per-patient costs associated with these comorbidities could amount to an enormous expenditure for payers. For example, in a hypothetical health plan of 100,000 lives (with 50,000 children and adolescents, respectively), the excess healthcare cost of $4,695 PPPY could amount to $7.1 million per year incremental to the cost burden associated with ADHD alone (Fig. 4). Sensitivity analyses varying ADHD prevalence estimates suggest that the incremental healthcare cost of comorbid anxiety and depression relative to ADHD alone in a hypothetical health plan of 100,000 lives could range from $2.9 to $10.6 million per year assuming an ADHD prevalence of 3.4–11.1% for children and 3.4–13.6% for adolescents [3,4,5,6,7,8].

Incremental cost of comorbid anxiety and/or depression in ADHD relative to ADHD alone in a simulated health plan. ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; FDA, Food and Drug Administration; US, United States. aA hypothetical value. bBased on the National Survey of Children’s Health data, 2018 [ 2 ]. cBased on Kessler et al., 2012 [ 3 ]. dBased on results in the current study

Findings of the current study are generally similar to a previous study among adults with ADHD, which found that comorbid anxiety and/or depression, especially when presented together, contributed to significant excess HRU and healthcare costs [27]. It has been previously shown that patients with ADHD who have comorbid anxiety and/or depression exhibit higher odds of treatment changes and incur higher associated costs relative to those with ADHD only [19], which may have partially contributed to the poorer clinical and economic outcomes among those with the comorbidities observed in the current study. It was also noted that treatment characteristics appear to be different among the pediatric and adult populations: a numerically higher proportion of pediatric patients received non-stimulants when anxiety and/or depression were present relative to adults with these comorbidities (22.7% vs. 6.8% at index; 21.1% vs. 5.3% during baseline) [27]. This may be due to some physicians being more cautious when considering stimulants for at-risk pediatric patients with comorbid emotional or behavioral conditions given the potential side effects of some medications on mood and emotion symptoms, despite their effectiveness [1]. Collectively, these observations highlight the need for improved management and treatment options to alleviate the burden associated with comorbidities in ADHD [28].

The current findings are also in line with the literature on HRU and economic burden of comorbidities among pediatric patients with ADHD [18, 29, 30]. A prior large US national survey reported that a higher proportion of pediatric patients with ADHD and comorbid emotional disturbances and depression, respectively, were hospitalized compared with those with the comorbidity only, and inpatient costs tended to be higher with the presence of both ADHD and the comorbidity [30]. Another US national survey found significantly greater odds of HRU (i.e., having ≥ 6 healthcare provider visits; ≥2 emergency room visits) among pediatric patients with ADHD and comorbid anxiety and depression, respectively [29]. Relative to the previous studies, the current study comprises more comprehensive HRU and cost categories, which provides insight on the overall clinical and economic burden attributable to anxiety and depression among those with ADHD. Furthermore, cost analyses among comorbidity subgroups also quantify the substantial impact to the healthcare system when both comorbid anxiety and depression are present in ADHD. Future studies investigating the impact of other psychiatric comorbidities on outcomes of pediatric patients with ADHD are warranted.

Managing ADHD and psychiatric comorbidities early in pediatric patients with ADHD may mitigate their burden in both the short-term and longer-term. In the short-term, reduced hospitalizations and psychotherapy visits may lead to less missed school days and better academic performances [31]. In the longer-term, certain childhood comorbidities, including anxiety and depression, have been shown to predict the development of other psychiatric comorbidities in later life [32]; therefore, a larger ADHD population may be affected by the impact of psychiatric comorbidities if the ADHD and its comorbid symptoms are not managed early. Indeed, the prevalence of comorbid anxiety and depression in ADHD appears to increase with age from childhood to adulthood [18, 19, 33]. In US population-based surveys, comorbid anxiety and depression have been reported in about 20% of pediatric patients with ADHD [18]; among adults, the prevalence of these comorbidities is up to 50% [33]. The respective prevalence of ADHD, anxiety, and depression have also been increasing in the US over the years, particularly among youths [34, 35], highlighting the urgency in addressing these psychiatric conditions at earlier stages to prevent their subsequent negative consequences in wider populations.

Findings of this study may help raise awareness to various stakeholders on the magnitude of the excess burden imposed by psychiatric comorbidities on pediatric patients with ADHD. For instance, parents and teachers may pay more attention to the emotional well-being of children and adolescents with ADHD and provide them with needed support to ease their anxiety or depression; clinicians may be more vigilant in considering the impact of psychiatric comorbidities in their ADHD management plan; and research efforts may be directed to exploring medications effective for improving both ADHD and comorbid psychiatric symptoms. These and other strategies may help alleviate the substantial burden associated with psychiatric comorbidities imposed on pediatric patients with ADHD and on the healthcare system at large.

Limitations

This study is subject to limitations inherent to retrospective databases using claims data, including potential data omissions, coding errors, and the presence of rule-out diagnosis (i.e., a record of an ADHD, an anxiety, or a depression diagnosis does not necessarily indicate that the patient has a true diagnosis). In addition, while cohorts were balanced based on observable characteristics, there may be residual confounding due to unobservable confounders; therefore, no causal inference can be made from this retrospective observational study. It should also be noted that the burden associated with anxiety and depression goes beyond HRU and healthcare costs, but this study was limited to information available in claims data; future research is warranted to explore other types of burden associated with comorbid anxiety and depression in ADHD. Finally, this study included only commercially insured patients and may not be representative of the pediatric population with ADHD in the US.

Conclusion

Comorbid anxiety and depression were associated with significantly increased risk of HRU and higher healthcare costs among pediatric patients with ADHD. In particular, the presence of both comorbid conditions resulted in 3.5 times higher excess costs relative to ADHD alone. Increased awareness of such burden and strategies to co-manage ADHD and psychiatric comorbidities are warranted to help mitigate the burden borne by patients and the healthcare system.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from IQVIA. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study. Data are available from the authors with the permission of IQVIA.

Abbreviations

- AMCP:

-

Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy

- FDA:

-

Food and Drug Administration

- HCUP:

-

Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project

- HIPAA:

-

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act

- HRSA:

-

Health Resources and Services Administration

- HRU:

-

Healthcare resource utilization

- NSCH:

-

National Survey of Children’s Health

- PPPY:

-

Per-patient-per-year

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- US:

-

United States

- USD:

-

United States dollar

References

Wolraich ML, Hagan JF Jr, Allan C, Chan E, Davison D, Earls M, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2019;144(4):e20192528.

Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative. National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH) data query: Data Resource Center for Child and Adolescent Health supported by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), Maternal and Child Health Bureau (MCHB); 2018 [cited 2021 June 21]. www.childhealthdata.org.

Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Costello EJ, Georgiades K, Green JG, Gruber MJ, et al. Prevalence, persistence, and sociodemographic correlates of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication adolescent supplement. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(4):372–80.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.); 2013.

Bitsko RH, Claussen AH, Lichstein J, Black LI, Jones SE, Danielson ML, et al. Mental health surveillance among children - United States, 2013–2019. MMWR Suppl. 2022;71(2):1–42.

Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative. National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH) data query: Data Resource Center for Child and Adolescent Health supported by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), Maternal and Child Health Bureau (MCHB); 2022 [cited 2024 April 18]. www.childhealthdata.org.

Polanczyk GV, Salum GA, Sugaya LS, Caye A, Rohde LA. Annual research review: a meta-analysis of the worldwide prevalence of mental disorders in children and adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2015;56(3):345–65.

Xu G, Strathearn L, Liu B, Yang B, Bao W. Twenty-year trends in diagnosed attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder among us children and adolescents, 1997–2016. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(4):e181471.

Galera C, Messiah A, Melchior M, Chastang JF, Encrenaz G, Lagarde E, et al. Disruptive behaviors and early sexual intercourse: the GAZEL Youth Study. Psychiatry Res. 2010;177(3):361–3.

Grygiel P, Humenny G, Rebisz S, Bajcar E, Switaj P. Peer rejection and perceived quality of relations with schoolmates among children with ADHD. J Atten Disord. 2018;22(8):738–51.

Molina BSG, Howard AL, Swanson JM, Stehli A, Mitchell JT, Kennedy TM, et al. Substance use through adolescence into early adulthood after childhood-diagnosed ADHD: findings from the MTA longitudinal study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2018;59(6):692–702.

Schein J, Adler LA, Childress A, Cloutier M, Gagnon-Sanschagrin P, Davidson M, et al. Economic burden of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder among children and adolescents in the United States: a societal perspective. J Med Econ. 2022;25(1):193–205.

Gnanavel S, Sharma P, Kaushal P, Hussain S. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and comorbidity: a review of literature. World J Clin Cases. 2019;7(17):2420–6.

Blackman GL, Ostrander R, Herman KC. Children with ADHD and depression: a multisource, multimethod assessment of clinical, social, and academic functioning. J Atten Disord. 2005;8(4):195–207.

Booster GD, Dupaul GJ, Eiraldi R, Power TJ. Functional impairments in children with ADHD: unique effects of age and comorbid status. J Atten Disord. 2012;16(3):179–89.

Klassen AF, Miller A, Fine S. Health-related quality of life in children and adolescents who have a diagnosis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics. 2004;114(5):e541–7.

Barbaresi WJ, Campbell L, Diekroger EA, Froehlich TE, Liu YH, O’Malley E, et al. The society for developmental and behavioral pediatrics clinical practice guideline for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with complex attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: process of care algorithms. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2020;41(Suppl 2):S58–74.

Larson K, Russ SA, Kahn RS, Halfon N. Patterns of comorbidity, functioning, and service use for US children with ADHD, 2007. Pediatrics. 2011;127(3):462–70.

Schein J, Childress A, Gagnon-Sanschagrin P, Maitland J, Bedard J, Cloutier M, et al. Treatment patterns among patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and comorbid anxiety and/or depression in the United States: a retrospective claims analysis. Adv Ther. 2023;40(5):2265–81.

Chan E, Zhan C, Homer CJ. Health care use and costs for children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: National estimates from the medical expenditure panel survey. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156(5):504–11.

Cuffe SP, Moore CG, McKeown R. ADHD and health services utilization in the national health interview survey. J Atten Disord. 2009;12(4):330–40.

Leibson CL, Katusic SK, Barbaresi WJ, Ransom J, O’Brien PC. Use and costs of medical care for children and adolescents with and without attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. JAMA. 2001;285(1):60–6.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 45 CFR 46: pre-2018 requirements [cited 2020 October 16]. https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/regulations/45-cfr-46/index.html#46.101.

Sharp SJ, Poulaliou M, Thompson SG, White IR, Wood AM. A review of published analyses of case-cohort studies and recommendations for future reporting. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(6):e101176.

Hainmueller J. Entropy balancing for causal effects: a multivariate reweighting method to produce balanced samples in observational studies. Political Anal. 2012;20(1):25–46.

Austin PC. Using the standardized difference to compare the prevalence of a binary variable between two groups in observational research. Commun Stat - Simul Comput. 2009;38(6):1228–34.

Schein J, Cloutier M, Gauthier-Loiselle M, Bungay R, Chen K, Chan D, et al. Healthcare resource utilization and costs associated with psychiatric comorbidities in adult patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2024. https://doi.org/10.18553/jmcp.2024.30.6.588.

Pozzi M, Carnovale C, Peeters G, Gentili M, Antoniazzi S, Radice S, et al. Adverse drug events related to mood and emotion in paediatric patients treated for ADHD: a meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2018;238:161–78.

Classi P, Milton D, Ward S, Sarsour K, Johnston J. Social and emotional difficulties in children with ADHD and the impact on school attendance and healthcare utilization. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2012;6(1):33.

Meyers J, Classi P, Wietecha L, Candrilli S. Economic burden and comorbidities of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder among pediatric patients hospitalized in the United States. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2010;4:31.

Black LI, Zablotsky B. Chronic school absenteeism among children with selected developmental disabilities: National Health interview Survey, 2014–2016. Natl Health Stat Rep. 2018;118:1–7.

Biederman J, Faraone S, Milberger S, Guite J, Mick E, Chen L, et al. A prospective 4-year follow-up study of attention-deficit hyperactivity and related disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53(5):437–46.

Kessler RC, Adler L, Barkley R, Biederman J, Conners CK, Demler O, et al. The prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(4):716–23.

Goodwin RD, Dierker LC, Wu M, Galea S, Hoven CW, Weinberger AH. Trends in U.S. depression prevalence from 2015 to 2020: the widening treatment gap. Am J Prev Med. 2022;63(5):726–33.

Oswalt SB, Lederer AM, Chestnut-Steich K, Day C, Halbritter A, Ortiz D. Trends in college students’ mental health diagnoses and utilization of services, 2009–2015. J Am Coll Health. 2020;68(1):41–51.

Acknowledgements

Medical writing assistance was provided by Flora Chik, PhD, MWC an employee of Analysis Group, Inc. and funded by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc.

Funding

This study was funded by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc. The study sponsor was involved in several aspects of the research, including the study design, interpretation of data, writing of the manuscript, and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MC, MGL, RB, KC, DC, and AG contributed to study conception and design, collection and assembly of data, and data analysis and interpretation. JS and AC contributed to study conception and design, data analysis and interpretation. All authors reviewed and approved the final content of this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Data analyzed in this study are de-identified and comply with the patient requirements of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA); therefore, no review by an institutional review board nor informed consent was required per Title 45 of CFR, Part 46.101(b)(4) [23].

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

JS is an employee of Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc. MC, MGL, RB, KC, DC, and AG are employees of Analysis Group, Inc., a consulting company that has provided paid consulting services to Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc. AC received research support from Allergan, Takeda/Shire, Emalex, Akili, Ironshore, Arbor, Aevi Genomic Medicine, Neos Therapeutics, Otsuka, Pfizer, Purdue, Rhodes, Sunovion, Tris, KemPharm, Supernus, and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration; was on the advisory board of Takeda/Shire, Akili, Arbor, Cingulate, Ironshore, Neos Therapeutics, Otsuka, Pfizer, Purdue, Adlon, Rhodes, Sunovion, Tris, Supernus, and Corium; received consulting fees from Arbor, Ironshore, Neos Therapeutics, Purdue, Rhodes, Sunovion, Tris, KemPharm, Supernus, Corium, Jazz, Tulex Pharma, and Lumos Pharma; received speaker fees from Takeda/Shire, Arbor, Ironshore, Neos Therapeutics, Pfizer, Tris, and Supernus; and received writing support from Takeda /Shire, Arbor, Ironshore, Neos Therapeutics, Pfizer, Purdue, Rhodes, Sunovion, and Tris.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Schein, J., Cloutier, M., Gauthier-Loiselle, M. et al. Healthcare resource utilization and costs associated with psychiatric comorbidities in pediatric patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a claims-based case-cohort study. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 18, 80 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-024-00770-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-024-00770-8