Abstract

Background

Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder is a common disorder that affects both children and adults. However, for adults, little is known about ADHD-attributable medical expenditures.

Objective

To estimate the medical expenditures associated with ADHD, stratified by age, in the US adult population.

Design

Using a two-part model, we analyzed data from Medical Expenditure Panel Survey for 2015 to 2019. The first part of the model predicts the probability that individuals incurred any medical costs during the calendar year using a logit model. The second part of the model estimates the medical expenditures for individuals who incurred any medical expenses in the calendar year using a generalized linear model. Covariates included age, sex, race/ethnicity, geographic region, Charlson comorbidity index, insurance, asthma, anxiety, and mood disorders.

Participants

Adults (18 +) who participated in the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey from 2015 to 2019 (N = 83,776).

Main Measures

Overall and service specific direct ADHD-attributable medical expenditures.

Key Results

A total of 1206 participants (1.44%) were classified as having ADHD. The estimated incremental costs of ADHD in adults were $2591.06 per person, amounting to $8.29 billion nationally. Significant adjusted incremental costs were prescription medication ($1347.06; 95% CI: $990.69–$1625.93), which accounted for the largest portion of total costs, and office-based visits ($724.86; 95% CI: $177.75–$1528.62). The adjusted incremental costs for outpatient visits, inpatient visits, emergency room visits, and home health visits were not significantly different. Among older adults (31 +), the incremental cost of ADHD was $2623.48, while in young adults (18–30), the incremental cost was $1856.66.

Conclusions

The average medical expenditures for adults with ADHD in the US were substantially higher than those without ADHD and the incremental costs were higher in older adults (31 +) than younger adults (18–30). Future research is needed to understand the increasing trend in ADHD attributable cost.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a neuropsychiatric disorder that is normally diagnosed in childhood but may persist into adulthood. According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5).1,2 ADHD is characterized by a repeated set of inattentive or hyperactive-impulsive behaviors that occurs throughout multiple settings and impairs social, academic, or occupational functionality.3 An estimated 10–60% of children with ADHD continue to experience symptoms throughout their lives.4 ADHD is a common psychiatric disorders experienced by adults,5 with a prevalence around 4.4%,6 and is one of the most commonly treated disorders in young adults.7

The negative social, emotional, and medical outcomes associated with ADHD have been well documented.8,9 Individuals with ADHD have poorer relationships with their family and friends10,11,12 are more likely to engage in illegal activities as they grow older,13 and struggle with self-esteem and overall satisfaction in life.14,15,16 In adulthood, individuals with ADHD are more likely to be incarcerated,17 divorced,18 or unemployed.19 Furthermore, ADHD has also been associated with several comorbid conditions, such as depression, anxiety, and substance abuse disorder that increase the disease burden on individuals.20

ADHD can pose a significant financial burden on individuals and families, through increased medical costs and productivity loss.21,22,23,24,25,26 Previous studies conducted in the US have found significantly higher medical costs for children/adolescents with ADHD than those without it.22 However, few US studies have examined ADHD-related medical expenditures in adults or examined how the cost changes throughout adulthood. Given the increase in the prevalence of ADHD over the years,27 updated information is needed about the specific direct medical costs associated with ADHD in adults.

The purpose of this study is to estimate the medical expenditures associated with ADHD, stratified by aged, in the US adult population.

Methods

Data Source

Data were obtained from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) for 2015–2019. MEPS data are a nationally representative sample of the US civilian noninstitutionalized population28. Detailed information on the MEPS data collection and sample design is provided by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ)29. Briefly, for households that participated in the study, 5 rounds of interviews were conducted within 2 years to collect a broad range of information about all members in the household. The survey collects information on self-reported sociodemographic characteristics, health status, health conditions, medical diagnosis, insurance status, use of healthcare services, expenditures for different types of services, and sources of payment. The occurrence of health conditions is determined primarily by prompting respondents of the household component for the causes of medical events and disability episodes for themselves or their family members or asking them about any health conditions that are bothering the person or their family members during the reference period30. These conditions are then coded by medical professionals, regardless of whether any medical expenses occurred in that year.

Due to the de-identified data, this study was exempt from institutional review board approval, per the US Department of Health and Human Services guidelines.

Study Sample

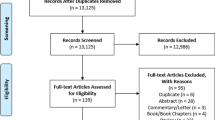

The inclusion criteria for this study was men and women aged 18 years or older. Individuals who reported a diagnosis of ADHD (ICD-9 = 314 or ICD-10 = F90) for the period January 1, 2015, to December 31, 2019, were classified as ADHD.31,32 After excluding individuals with missing values on key variables, the final sample included 83,776 adults.

Measures

The dependent variables for this study were the direct overall medical expenditures and the service specific medical expenditures. This included hospital stays, outpatient care, emergency room visits, physician office visits, home care visits, and prescription medication. Household members were asked about which medical services each family member used and the corresponding medical costs that occurred. These costs included respondents’ out of pocket payments and payments from private/public health insurance but did not include over-the-counter drugs, as these were not collected by MEPS. Following the guidelines recommend by AHRQ, costs were inflated to the recent estimate of the 2019-dollar value using the Personal Health Care Price Indices.33

From the literature, two groups of variables, patient characteristics and medical conditions, were identified as potential predictors of the medical expenditures of ADHD. Patient characteristics included age, gender, race/ethnicity, geographic region, marital status, employment status, education, poverty, and insurance type.5,25 Depending on the year the data was collected, medical conditions were defined using ICD-10-CM codes or the clinical classification codes generated from Clinical Classification Software (CCS).34 Medical conditions included an adapted Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), asthma (CCS = 128 or ICD-10 = J45), anxiety disorders (anxiety, social phobia, and obsessive–compulsive disorder) (CCS = 651 or ICD-10 = F40/F41), and mood disorders (depression, bipolar) (CCS = 657 or ICD-10 = J31/J32).4,5 The CCI is a commonly used method of categorizing medical comorbidities of patients based on their ICD codes.35 The CCI score was calculated using Stata’s Charlson package, which is based on the adaptations of Deyo and Quan to accommodate ICD-9-CM codes and ICD-10-CM codes.36,37,38 For this study, the CCI was grouped into 3 categories: 0, 1, ≥ 2. Asthma was included as a covariate in the model due the high comorbidity found between ADHD and asthma.4 Although the exact nature of the association is not fully understood, numerous studies have observed the association in adults and children, and in population and clinical settings.39 Anxiety disorders and mood disorders have also been found to have a significant association with ADHD in adults and were thus included in the final model.5,40 Alcohol- and drug-related abuse were not adjusted in the model as previous research found that ADHD generally precedes these behaviors, and that ADHD can contribute to their development.41,42

Data Analytic Procedures

Bivariate analysis was conducted between individuals with ADHD and those without ADHD using chi-square statistics for categorical variables and t-statistics for continuous variables. Next, a two-part model was used to estimate the overall and service specific medical expenditures associated with ADHD in US adults. A two-part model was chosen due to the large number of individuals who reported zero medical costs within the calendar year.43,44 The first part of the model predicts the probability that individuals incurred any medical costs during the calendar year using a logit model. The second part of the model estimates the medical expenditures for individuals who incurred any medical expenses in the calendar year using a generalized linear model. The modified park test was used to select the distribution and variance function for the generalized linear model, resulting in gamma or Poisson distribution and a log link function. Covariates included in both parts of the model were age, sex, race, ethnicity, geographic region, insurance type, CCI, asthma, anxiety, and mood disorders. Stratified analysis was conducted by age for younger adults (18-30) and older adults (31 +).

Based on the two regression models, per-person expenditures associated with ADHD were calculated through several steps.45 First, assuming everyone had ADHD (A), second assuming everyone did not have ADHD (B), and finally determining the incremental costs of ADHD by subtracting the predicted costs when everyone did not have ADHD from the predicted costs when everyone did have ADHD (A-B). This difference was then multiplied by the average number of individuals with ADHD to estimate the national economic burden of ADHD. The number of individuals with ADHD was estimated directly from MEPS by applying sampling weights, using all possible individuals. Sampling weights were taken into account in all cost estimation analysis, which were 5-year pooled sampling weights averaged by the number of panels (N = 5). The bootstrap method with 100 replicates was used to derive standard errors (SEs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

All analyses were conducted using Stata software (version 15.1, StataCorp, College Station, TX) and statistical significance was determined at a p-value of 0.05.

Results

In the study population (Table 1), 1.44% (1206/83,776) were identified as having ADHD. Individuals in the study population were primarily female (51.70%), were employed (63.40%), and had high income (44.52%), and there was no statistically significant differences between the groups for these variables. Overall, the mean unadjusted annual medical expenditures were $6853.91 (SE: 99.21) for all individuals in the study population, with individuals with ADHD ($8589.61 ± 641.94) having significantly higher expenditures than those without ADHD ($6821.72 ± 98.25; p = 0.005). When only including patients who had a medical expenditure, the overall unadjusted mean medical expenditures was $8009.25 (SE: 111.43), and the difference between for those with ADHD ($8697.59 ± 649.89) vs those without ADHD ($7994.45 ± 110.54) was insignificant.

Individuals with ADHD were significantly different from those without ADHD regarding patient characteristics and medical conditions. For patient characteristics, individuals with ADHD were more likely to be younger (34.63 vs. 47.82, p < 0.001), more likely to be White (82.14% vs. 62.59%, p < 0.001), and more likely to have private insurance (76.57% vs. 69.80%, p < 0.001). In contrast, individuals without ADHD were more likely to be married (52.28% vs 33.34%, p < 0.001) and have the highest educational attainment be a high school degree or equivalent (41.85% vs. 35.14%, p = 0.004). Medically, individuals with ADHD were more likely to report asthma, mood disorders, and anxiety.

After controlling for covariates, individuals with ADHD were 12.30 times more likely (95% CI: 6.82–22.20; p < 0.001) than individuals without ADHD to have an expenditure of at least $1, and among individuals with positive expenditures, those with ADHD had 28% (exp[0.25]) higher expenditures than individuals without ADHD (β = 0.25; 95% CI: 0.10–0.40; p = 0.001) (Table 2). The total incremental costs of ADHD were estimated at $2591.06 (95% CI: $1471.71–$4684.57) (Table 3). The adjusted incremental costs in prescription medication accounted for the largest portion of the total costs, at $1347.06 (95% CI: $990.69–$1625.93). The only other statistically significant adjusted incremental cost was for office-based visits ($724.86; 95% CI $177.75–$1528.62). When estimating costs at the national level, a total of $8.29 billion was attributable to adult ADHD, with $4.31 billion specifically attributable to ADHD prescription costs.

The adjusted odds of having a medical expenditure of at least $1 were 9.21 times higher (95% CI: 4.66–17.99; p < 0.001) in individuals with ADHD than individuals without ADHD in adults 18–30 and 28.50 times higher (95% CI: 8.50–91.84; p < 0.001) in adults 31 + (Table 4). Among individuals with positive medical expenditures, adults 18–30 with ADHD had 39% higher expenditures (β = 0.33; 95% CI: 0.03–0.63; p = 0.029) than adults without ADHD and adults 31 + with ADHD had 25% higher expenditures (β = 0.22; 95% CI: 0.04–0.41; p = 0.018). The total incremental cost was higher in adults 31 + than among younger adults 18–30, $2623.48 (95% CI: $997.94–$5012.65) and $1856.66 (95% CI: $864.01–3,455.02) respectively (Table 5). Incremental expenditures associated with prescription medication accounted for the largest portion of the total costs in both age groups and was higher in older adults aged 31 + ($1339.74; 95% CI: $707.62–$1796.89) than younger adults aged 18–30 ($722.10; 95% CI: $493.06–$1029.96). Conversely, younger adults with ADHD had higher adjusted incremental expenditures for office base visits ($627.28; 95% CI: $322.09–$1507.26) than older adults ($449.53; 95% CI: $130.034–$945.71). The adjusted incremental expenditures for inpatient visits, outpatient visits, emergency room visits, and home health visits were not statistically different in either age group.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to estimate the medical expenditures associated with ADHD, stratified by age, in the US adult population. Overall, the estimated incremental cost of ADHD in adults was $2591.06 per person, amounting to $8.29 billion nationally. In older adults (31 +), the incremental cost of ADHD was $2623.48, while in younger adults (18-30) the incremental cost was $1856.66. The largest proportion of medical expenditures across all age groups was associated with prescription medication.

Our study demonstrates that individuals with ADHD incurred higher medical expenditures compared to individuals without ADHD. The estimated incremental costs of ADHD per person found in this study are consistent with previous studies conducted in the US, highlighting the continued impact of ADHD on medical expenditures.45,46 In 2011, Hodgkins et al. analyzed data from two large healthcare claims and productivity databases and found adults with ADHD incurred an excess of $2100.76 (adjusted to 2019-dollar) more in medical expense.5 More recently, Shah and Onukwugha analyzed MEPS data from 2017 to 2018 and found that working adults with ADHD incurred $4328 more than working adults without ADHD.46 Although their findings of the total costs of ADHD are higher than ours, this is likely due to the differences in inclusion criteria for their study sample, which was restricted to adults who were employed in the study year. Employment status has a significant impact of healthcare utilization and costs, with unemployed individuals less likely to visit physicians for preventative services and less likely to fill prescriptions.47,48 This impact may be even greater in individuals diagnosed with ADHD, as ADHD medication can be expensive and often requires frequent visits to the physician for proper management.49,50 By including all adults, regardless of insurance or employment, our findings allow for a more complete understanding of the financial impact of ADHD in adults.

On a national level, the estimated $8.29 billion for total medical costs is consistent with findings from previous studies of $1.32–$39.79 billion (adjusted to 2019-dollar value).25 These results indicate that the medical cost of ADHD has a substantial economic impact in the US and policy initiatives might be needed to alleviate this economic burden. This is especially troubling since ADHD also results in additional costs to society, such productivity and income loss, education, and justice system.25,51 Furthermore, although the ADHD prevalence found in our study, 1.44%, is similar to the prevalence found in a recent study using Kaiser Permanente data27, 1.12%, it is less than the 4.4% that is commonly cited by other studies.25,51 Therefore, our estimated medical expenditures associated with ADHD at the national level are a relatively conservative assessment.

In this study, stratification into two age groups provided additional insights into ADHD medical expenditures. We found that ADHD medical expenditures were higher in older adults (31 +) than younger adults (18-30), which is consistent with a recent study conducted in Germany.52 This extra burden of medical expenditure among older adults with ADHD might reflect the lifetime accumulative burden of illness from ADHD, a topic which deserves more academic and clinical attention (e.g., from the perspective of chronic disease management, healthy aging among older adults with ADHD, healthcare cost-saving among older adults with ADHD). More research is needed to understand why the incremental cost is so much higher in older adults than in younger adults and how to address this increased cost.

In our study, prescription medication was the largest component of the total medical expenditures for ADHD for all adults, and within each age group. These findings are consistent with previous studies of adult and children/adolescent populations.23,46 Although there are several treatment options for individuals with ADHD, pharmacological treatments, i.e. medications, are the most commonly utilized.53 Consequently, this leads to higher medical expenditures due to prescription medication in individuals with ADHD. However, other potential treatment options, such as mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, need to be explored more fully.54 Unfortunately, the majority of cost-effectiveness research on the treatment of ADHD has been focused on children.53 Our findings indicate that more cost-effectiveness research for ADHD treatment is needed in adults to provide affordable, high-quality care for everyone with ADHD.

As compared with past studies, one of the main strengths of our study is that it used a large, nationally representative sample to estimate medical expenditures, including individuals with and without insurance and nonworking adults. This allows for the fact that individuals with ADHD could have difficulty with employment, which affects their likelihood of having insurance and thus did not enter the data sources provided by payers.55 Another strength of MEPS data is that it includes the total payments respondents reported which were paid. Finally, this study used a two-part model to estimate the medical expenditures. The two-part model has a long history in health economics and health services research due to its ability to model continuous, non-negative outcome measures.56 The model is able to handle data that has a skewed conditional distribution, a large number of zero values, and allows for investigation of the effects of demographic and clinical comorbidities on both the logit model and GLM model separately.56,57

This study has several limitations. First, the MEPS data is based on self-reported responses and only includes ADHD if an individual is currently being managed for the disorder or it is identified as a current problem. This might explain why our estimates of ADHD rate (1.44%) are lower than some worldwide estimates (1.0–5.4%).58 Second, current DSM-5 criteria for ADHD have been criticized for having low clinical thresholds, which results in a misclassification of individuals who do not experience the symptoms of ADHD being classified with the diagnosis.59,60 In our study, this would lead to an underestimation of the medical expenditures associated with ADHD since not all individuals in the ADHD cohort would truly have the diagnosis. Third, our national cost estimates were likely to be underestimated because MEPS did not include people who were incarcerated. This is important because the ADHD rates have been reported as high as 25.5% in prisoners.40 Fourth, as MEPS data is cross-sectional, the results can only be interpreted as medical expenditures associated with ADHD and cannot account for costs associated with ADHD over a lifetime. Finally, our study did not include indirect cost associated with ADHD, such as productivity and income loss, education, and justice system.

Conclusion

ADHD is a common psychiatric disorder that impacts a large number of adults in the US. We found that the average medical expenditures for adults with ADHD in the US were substantially higher than those without ADHD and the incremental costs were higher in older adults (31 +) than in younger adults (18-30).

Data Availability

The datasets analyzed for this study are publicly available and are provided by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (https://www.meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/).

References

Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders : DSM-5. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

Epstein JN, Loren RE. Changes in the definition of ADHD in DSM-5: subtle but important. Neuropsychiatry. 2013;3(5):455.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®). Washington: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

Secnik K, Swensen A, Lage MJ. Comorbidities and costs of adult patients diagnosed with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Pharmacoeconomics. 2005;23(1):93-102.

Hodgkins P, Montejano L, Sasané R, Huse D. Cost of illness and comorbidities in adults diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a retrospective analysis. The primary care companion to CNS disorders. 2011;13(2).

Kessler RC, Adler L, Barkley R, Biederman J, Conners CK, Demler O, et al. The prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the United States. Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication;2006:163.

Johansen ME, Matic K, McAlearney AS. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder medication use among teens and young adults. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2015;57(2):192-7.

Anderson J. Reported Diagnosis and Prescription Utilization Related to Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Children Ages 5–17, 2008–2015. . 2018 August(Statistical Brief#514).

Das D, Cherbuin N, Easteal S, Anstey KJ. Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder symptoms and cognitive abilities in the late-life cohort of the PATH through life study. PloS one. 2014;9(1):e86552.

Hoza B. Peer functioning in children with ADHD. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007;32(6):655-63.

Harpin VA. The effect of ADHD on the life of an individual, their family, and community from preschool to adult life. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90(suppl 1):i2-7.

Johnston C, Mash EJ. Families of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: review and recommendations for future research. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2001;4(3):183-207.

Lichtenstein P, Halldner L, Zetterqvist J, Sjölander A, Serlachius E, Fazel S, et al. Medication for attention deficit–hyperactivity disorder and criminality. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(21):2006-14.

Brod M, Schmitt E, Goodwin M, Hodgkins P, Niebler G. ADHD burden of illness in older adults: a life course perspective. Quality of Life Research. 2012;21(5):795-9.

Biederman J, Faraone S, Spencer T, Mick E, Monuteaux M, Aleardi M. Functional impairments in adults with self-reports of diagnosed ADHD. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(4):524-40.

Coghill D. The impact of medications on quality of life in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. CNS drugs. 2010;24(10):843-66.

Curran S, Fitzgerald M. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in the prison population. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(10):1664-5.

Lamberg L. ADHD often undiagnosed in adults. JAMA. 2003;290(12):1565-7.

Mulsow MH, O'NEAL KK, Murry VM. Adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, the family, and child maltreatment. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2001;2(1):36–50.

Katzman MA, Bilkey TS, Chokka PR, Fallu A, Klassen LJ. Adult ADHD and comorbid disorders: clinical implications of a dimensional approach. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):1-15.

Asherson P, Akehurst R, Kooij JS, Huss M, Beusterien K, Sasané R, et al. Under diagnosis of adult ADHD: cultural influences and societal burden. Journal of Attention Disorders. 2012;16(5_suppl):20S-38S.

Matza LS, Paramore C, Prasad M. A review of the economic burden of ADHD. Cost effectiveness and resource allocation. 2005;3(1):5.

Gupte-Singh K, Singh RR, Lawson KA. Economic burden of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder among pediatric patients in the United States. Value in Health. 2017;20(4):602-9.

Holden SE, Jenkins-Jones S, Poole CD, Morgan CL, Coghill D, Currie CJ. The prevalence and incidence, resource use and financial costs of treating people with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in the United Kingdom (1998 to 2010). Child and adolescent psychiatry and mental health. 2013;7(1):34.

Doshi JA, Hodgkins P, Kahle J, Sikirica V, Cangelosi MJ, Setyawan J, et al. Economic impact of childhood and adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the United States. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2012;51(10):990,1002. e2.

Chan E, Zhan C, Homer CJ. Health care use and costs for children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: national estimates from the medical expenditure panel survey. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156(5):504-11.

Chung W, Jiang S, Paksarian D, Nikolaidis A, Castellanos FX, Merikangas KR, et al. Trends in the prevalence and incidence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder among adults and children of different racial and ethnic groups. JAMA network open. 2019;2(11):e1914344.

Cohen JW, Cohen SB, Banthin JS. The medical expenditure panel survey: a national information resource to support healthcare cost research and inform policy and practice. Med Care. 2009:S44–50.

MEPS-HC Panel Design and Collection Process [Internet]. [cited May 12, 2021]. Available from: https://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/survey_comp/hc_data_collection.jsp.

Machlin S, Soni A, Fang Z. No title. Understanding and analyzing MEPS household component medical condition data. 2010.

World Health Organization. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems: 10th revision (ICD-10). http://www.who.int/classifications/apps/icd/icd. 1992.

Healthcare cost & Utilization Project CCS [Internet].; 2017 [updated March; cited August 5, 2022]. Available from: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jsp.

Dunn A, Grosse SD, Zuvekas SH. Adjusting health expenditures for inflation: a review of measures for health services research in the United States. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(1):175-96.

Elixhauser A. Clinical classifications for health policy research: Hospital inpatient statistics, 1995. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Agency for …; 1998.

D'Hoore W, Bouckaert A, Tilquin C. Practical considerations on the use of the Charlson comorbidity index with administrative data bases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49(12):1429-33.

Stagg V. CHARLSON: Stata module to calculate Charlson index of comorbidity. . 2017.

Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(6):613-9.

Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, Fong A, Burnand B, Luthi J, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005:1130–9.

Leffa DT, Caye A, Santos I, Matijasevich A, Menezes A, Wehrmeister FC, et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder has a state-dependent association with asthma: The role of systemic inflammation in a population-based birth cohort followed from childhood to adulthood. Brain Behav Immun. 2021;97:239-49.

Young S, Sedgwick O, Fridman M, Gudjonsson G, Hodgkins P, Lantigua M, et al. Co-morbid psychiatric disorders among incarcerated ADHD populations: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2015;45(12):2499-510.

Smith BH, Molina BS, Pelham Jr WE. The clinically meaningful link between alcohol use and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Alcohol Research & Health. 2002;26(2):122.

Davis C, Cohen A, Davids M, Rabindranath A. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in relation to addictive behaviors: a moderated-mediation analysis of personality-risk factors and sex. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2015;6:47.

Buntin MB, Zaslavsky AM. Too much ado about two-part models and transformation?: Comparing methods of modeling Medicare expenditures. J Health Econ. 2004;23(3):525-42.

Mullahy J. Much ado about two: reconsidering retransformation and the two-part model in health econometrics. J Health Econ. 1998;17(3):247-81.

Zhang D, Wang G, Zhang P, Fang J, Ayala C. Medical expenditures associated with hypertension in the US, 2000–2013. Am J Prev Med. 2017;53(6):S164-71.

Shah CH, Onukwugha E. Direct medical and indirect absenteeism costs among working adult ADHD patients in the United States. Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research. 2022(just-accepted).

Tefft N, Kageleiry A. State‐level unemployment and the utilization of preventive medical services. Health Serv Res. 2014;49(1):186-205.

Nguyen A, Guttentag A, Li D, Meijgaard Jv. The Impact of Job and Insurance Loss on Prescription Drug use: A Panel Data Approach to Quantifying the Health Consequences of Unemployment During the Covid-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Health Services. 2022:00207314221078749.

Piper BJ, Ogden CL, Simoyan OM, Chung DY, Caggiano JF, Nichols SD, et al. Trends in use of prescription stimulants in the United States and Territories, 2006 to 2016. PloS one. 2018;13(11):e0206100.

Fields SA, Johnson WM, Hassig MB. Adult ADHD: Addressing a unique set of challenges. J Fam Pract. 2017;66(2):68-74.

Barkley RA. The High Economic Costs Associated with ADHD. The ADHD Report. 2020;28(3):10-2.

Libutzki B, Ludwig S, May M, Jacobsen RH, Reif A, Hartman CA. Direct medical costs of ADHD and its comorbid conditions on basis of a claims data analysis. European Psychiatry. 2019;58:38-44.

Dijk HH, Wessels LM, Constanti M, van den Hoofdakker BJ, Hoekstra PJ, Groenman AP. Cost-Effectiveness and Cost Utility of Treatment of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: A Systematic Review. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2021;31(9):578-96.

Janssen L, Kan CC, Carpentier PJ, Sizoo B, Hepark S, Schellekens MP, et al. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy v. treatment as usual in adults with ADHD: a multicentre, single-blind, randomised controlled trial. Psychol Med. 2019;49(1):55–65.

Gjervan B, Torgersen T, Nordahl HM, Rasmussen K. Functional impairment and occupational outcome in adults with ADHD. Journal of attention disorders. 2012;16(7):544-52.

Belotti F, Deb P, Manning WG, Norton EC. Tpm: estimating two-part models. Stata J. 2012;5(2):1-13.

Deb P, Norton EC. Modeling health care expenditures and use. Annu Rev Public Health. 2018;39:489-505.

Simon V, Czobor P, Bálint S, Mészáros A, Bitter I. Prevalence and correlates of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: meta-analysis. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;194(3):204-11.

Gascon A, Gamache D, St‐Laurent D, Stipanicic A. Do we over‐diagnose ADHD in North America? A critical review and clinical recommendations. J Clin Psychol. 2022.

Fabiano F, Haslam N. Diagnostic inflation in the DSM: A meta-analysis of changes in the stringency of psychiatric diagnosis from DSM-III to DSM-5. Clin Psychol Rev. 2020;80:101889.

Acknowledgements

BW and BH effort was supported by NIH NIGMS 2U54GM104942-07 and NIH NIMHD RADx-Up 1U01MD017419-01.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number 2U54GM104942-07.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Ethics declarations

Competing Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Disclaimer

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Witrick, B., Zhang, D., Su, D. et al. Medical Expenditures Associated with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Among Adults in the United States by Age, 2015–2019. J GEN INTERN MED 38, 2082–2090 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-023-08075-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-023-08075-w