Abstract

Background

Building healthcare service and health professionals’ capacity and capability to rapidly translate research evidence into health practice is critical to the effectiveness and sustainability of healthcare systems. This review scoped the literature describing programmes to build knowledge translation capacity and capability in health professionals and healthcare services, and the evidence supporting these.

Methods

This scoping review was undertaken using the Joanna Briggs Institute scoping review methodology. Four research databases (Ovid MEDLINE, CINAHL, Embase, and PsycInfo) were searched using a pre-determined strategy. Eligible studies described a programme implemented in healthcare settings to build health professional or healthcare service knowledge translation capacity and capability. Abstracts and full texts considered for inclusion were screened by two researchers. Data from included papers were extracted using a bespoke tool informed by the scoping review questions.

Results

Database searches yielded 10,509 unique citations, of which 136 full texts were reviewed. Thirty-four papers were included, with three additional papers identified on citation searching, resulting in 37 papers describing 34 knowledge translation capability building programmes.

Programmes were often multifaceted, comprising a combination of two or more strategies including education, dedicated implementation support roles, strategic research-practice partnerships and collaborations, co-designed knowledge translation capability building programmes, and dedicated funding for knowledge translation. Many programmes utilised experiential and collaborative learning, and targeted either individual, team, organisational, or system levels of impact. Twenty-seven programmes were evaluated formally using one or more data collection methods. Outcomes measured varied significantly and included participant self-reported outcomes, perceived barriers and enablers of knowledge translation, milestone achievement and behaviour change. All papers reported that programme objectives were achieved to varying degrees.

Conclusions

Knowledge translation capacity and capability building programmes in healthcare settings are multifaceted, often include education to facilitate experiential and collaborative learning, and target individual, team, organisational, or supra-organisational levels of impact. Although measured differently across the programmes, the outcomes were positive. The sustainability of programmes and outcomes may be undermined by the lack of long-term funding and inconsistent evaluation. Future research is required to develop evidence-informed frameworks to guide methods and outcome measures for short-, medium- and longer-term programme evaluation at the different structural levels.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Researchers, health policymakers, leaders, educators, and health-research collaboratives are becoming increasingly interested in effective ways to rapidly translate research into practice to improve healthcare delivery systems, and ultimately, health outcomes [1,2,3]. The field of implementation science has exploded over the past two decades, as more evidence has been generated to support strategies for translating research evidence into health practice and policy successfully, sustainably, and at scale [4]. Concurrently, there is growing recognition of the need to develop capacity within healthcare settings and among health professionals to promote evidence-based knowledge translation practices, and enable the consistent, timely and sustained use of research evidence in health practice [3, 5, 6]. This recognition has led to the emergence of education programmes in the field of implementation and dissemination science; many of which have been led by universities and target academic researchers [7, 8]. Few education programmes have specifically focused on developing knowledge translation skills in health professionals [4]. Developing the capacity and capability of healthcare services and health professionals to adopt, adapt, and implement research evidence is critical to the sustainability of healthcare delivery systems [3, 5]. For this paper, the term capacity is defined as the readiness of and access to resources needed for individuals and organisations to engage in knowledge translation. Capability is defined as individuals’ knowledge and skills required to engage in translation practice [9, 10].

Initiatives such as the establishment of research translation centres, academic health science centres and clinical research networks have also sought to drive integrated evidence-based healthcare delivery [11]. Investment has been made in the strategic implementation of roles such as embedded researchers [12], knowledge brokers [2, 13], mentors [14], and implementation support practitioners [3], in a bid to support the active, timely and sustained translation of research in healthcare settings. The existing evidence supporting the implementation, outcomes and sustainability of these, and other strategies, to promote the translation of research into healthcare practice, has not been reviewed systematically.

This review was undertaken as part of a broader programme of work to promote the rapid translation of research knowledge into rural and regional healthcare settings. Currently, published reviews of strategies to build knowledge translation capacity have focused predominantly on education, training and initiatives led by academic institutions and targeting either academic researchers or a mix of researchers and health professionals [4, 8]. Other reviews have focused on programmes to develop evidence-based practice knowledge, skills and capabilities for health professionals to conduct practice-based research [15, 16]. Another published review investigated the accessibility of online knowledge translation learning opportunities available for health professionals [17]. This current review aims to fill the gap in the literature by scoping the evidence on programmes that aim to build capacity and capability within settings in which healthcare is delivered to patients or consumers (healthcare settings) and in health professionals, to implement research in practice.

A search of Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Joanna Briggs Institute’s (JBI) Evidence Synthesis, PROSPERO and Google Scholar for reviews of knowledge translation capacity and capability building programmes and models in healthcare settings, yielded no existing or planned reviews. The decision to undertake a scoping review, rather than a conventional systematic review, was based on three key factors: (1) the heterogeneity evident in knowledge translation capacity and capability building programmes and models implemented in healthcare settings; (2) the absence of an existing synthesis of evidence for knowledge translation capacity and capability building programmes delivered in healthcare settings or for health professionals and (3) the need to identify the gaps in knowledge about these types of programmes [18].

This scoping review aimed to scope the literature describing programmes or models designed to build capacity and capability for knowledge translation in healthcare settings, and the evidence supporting these programmes and models. The specific review questions were:

-

(1)

What models or approaches are used to develop knowledge translation capacity and capability in healthcare settings?

-

(2)

How are the models and approaches to building knowledge translation capacity and capability funded, and the efforts sustained in healthcare settings?

-

(3)

How are these models or approaches evaluated and what types of outcomes are reported?

Methods

This review used the JBI scoping review methodology. Search terms were developed for population, concept and context (PCC). The review questions, inclusion and exclusion criteria and search strategies were developed in advance (Additional File 1 Scoping Review Protocol). The review is reported in line with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) extension for scoping reviews (Additional File 2 PRISMA-ScR checklist [19].

Search strategy

The JBI three-step search strategy was applied. The researchers identified a set of key papers based on their knowledge of knowledge translation capacity and capability building programmes. These papers were used to identify key search terms. In consultation with the research librarians (FR and JS; see “Acknowledgements”), the research team conducted preliminary scoping searches to test the search terms and strategy and refine the final search terms. A tailored search strategy using the search terms was developed for each academic database (Additional file 3 Search Strategy).

Academic databases searched included Ovid MEDLINE, CINAHL, Embase and PsycInfo. Selected grey literature platforms, based on the researchers’ knowledge of relevant websites and organisations, were searched. Where larger search yields were observed (e.g. via Google and Google Scholar), the first 250 items were reviewed (Additional file 4 Grey Literature Searches). The final research database searches were conducted on 30th December 2022 by a researcher with extensive systematic literature searching experience (EW) in consultation with the research librarians. Grey literature searches were conducted on 15th March 2023. Searches of the reference lists of included records and forward citation searches were undertaken.

Inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria

Literature was selected according to predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria developed using the PCC framework (see Table 1). Research education or capacity-building programmes delivered to qualified health professionals, working in healthcare settings in high-income countries (HIC) as defined by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) [20], were included. The HICs criteria was included to introduce a level of homogeneity around the broader resource contexts of the study populations [21]. No date limits were applied, and all types of literature published up to 30 December 2022 were included. Literature published in English only was included, due to resource limitations.

Study selection, quality appraisal and data extraction

Citations were imported into Covidence (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia) for screening. Titles and abstracts were screened independently by two reviewers, with conflicts resolved by a third independent reviewer. Similarly, full texts were reviewed by two researchers and the reasons for exclusion were documented (Additional file 5 Excluded Studies). Data were extracted from the included texts by two independent researchers. All texts were reviewed by a second researcher to ensure the accuracy and consistency of data extraction. Formal quality appraisal was not undertaken as part of the scoping review, in line with this methodology [18].

Extracted data were tabulated and results were synthesised using a descriptive approach guided by the review objectives. The distinction between capacity and capability building strategies described in the papers was not drawn or analysed as part of this review. Outcomes measured and reported in the papers were synthesised descriptively as guided by the review objectives, the scoping review methodology and drawing on Cooke’s framework [22]. Although Cooke’s framework was initially developed for evaluating research capacity building, the four structural levels of impact are also relevant to informing and evaluating approaches to build capacity for research building for impact on health practice [23]. Sustainability, although not included as a key concept in the initial database searches, was considered in relation to both programme funding and the maintenance and spread of the programme outcomes [24]. Sustainability features were identified throughout the data extraction and synthesis processes.

Results

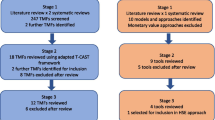

Of the 10,509 titles and abstracts that were screened, 136 were included for full text screening. Of these, 34 met the inclusion criteria and the reasons for exclusion of 102 articles are shown in Fig. 1. Through citation search of the initial set, which involved hand-searching of reference lists, and forward searching of citations, an additional three papers were identified [25].

Knowledge translation capacity and capability building programme delivery

A total of 37 papers, examining 34 knowledge translation capacity and capability building programmes were included in this review. The summary of the knowledge translation capability building programmes and their characteristics are shown in Table 2. Programmes were delivered in Australia [6, 26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38], Canada [39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47], England [48,49,50,51,52], the United States of America [53,54,55], Sweden [56, 57], Scotland [58], Saudi Arabia [59] and in multiple countries [11, 60] and were implemented from 1999 to 2021. Programmes tended to target a mix of health and research professionals; however, some targeted specific groups including allied health [26, 27, 29, 32, 35,36,37, 55], nurses [34, 45, 49], doctors [59], managers [57] and cancer control practitioners [53].

Strategies for building knowledge translation capacity and capability in health professionals and healthcare settings

Various capacity and capability building strategies were identified in the programmes. More than half of the programmes were described as using a combination of two or more strategies to build knowledge translation capability [6, 11, 26, 27, 30, 32, 33, 36,37,38,39,40,41,42, 46, 47, 49, 52, 55,56,57,58]. Programmes commonly involved targeted training and education for individuals and teams, delivered predominantly in the healthcare workplace, with few delivered in universities [31, 51, 59, 60], or other settings (e.g. partnership organisations) [28, 47]. Education was frequently employed in concert with other strategies such as dedicated implementation support roles [6, 26, 27, 32, 36,37,38,39,40,41,42, 46, 47, 49, 52, 55,56,57,58].

Other initiatives included strategic research-practice partnerships, typically between a health service and academic institution [11, 28, 38, 49], collaboratives (three or more research-interested organisations) [11, 32, 33, 40,41,42, 46,47,48, 52, 56, 58], co-designed knowledge translation capacity-building programmes with health professionals or health programme managers [11, 26, 27, 36, 37, 47, 57, 58], and dedicated funding for knowledge translation initiatives [33, 39]. The programmes reporting isolated strategies utilised education [31, 34, 43, 44, 51, 53, 54, 59, 60], a support role [29, 35, 45, 50] and research-practice partnerships [28].

The duration of the programmes varied significantly from 1-day workshops to upskill implementation leads [6] to comprehensive 3-year support programmes [39]. In some cases, programmes involving the implementation of a support role were described as ongoing [29, 35].

Pedagogical principles and theoretical frameworks

The pedagogical principles or learning theories underpinning the capability building programmes were rarely described explicitly, but rather were implied in the descriptions of the programmes. Many programmes purposefully made time in the curriculum for group work to foster connections with peers and promote social learning [6, 11, 26,27,28, 33, 34, 36,37,38, 40,41,42, 44, 46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60]. Further, experiential learning or “learning by doing” whereby participants applied their new knowledge and skills to a real-world project or knowledge translation initiative [61] was commonly described as a core component of capability building programmes [6, 26,27,28, 30, 31, 34, 36,37,38,39,40, 43, 44, 46, 47, 49,50,51, 53,54,55,56,57, 59]. Passive learning through didactic teaching (e.g. via lectures, seminars or webinars) was a common feature of education strategies [6, 31, 39, 43, 44, 46, 49, 51,52,53,54,55,56, 58,59,60]. Many programmes also incorporated individual or team-based mentoring with a more experienced knowledge translation specialist or researcher [26,27,28,29,30, 32, 35,36,37, 39,40,41,42, 44,45,46, 54, 55]. Behaviour change theory or techniques were referenced by a few studies [6, 43, 57]. Self-efficacy theory informed three programmes [34, 36, 37, 44]. Finally, one programme incorporated debate as a pedagogy [59].

Programme funding and sustained outcomes of the knowledge translation capacity and capability efforts

Sources of funding for the programmes included research institutes (e.g. Swedish Research Council, NIHR, Canadian Institutes of Health Research) [6, 11, 39,40,41,42, 44, 45, 47,48,49,50, 52, 60], government health departments (e.g. ministries or states responsible for health funding) [11, 26, 27, 32, 33, 53, 59], health services or academic health science centres [29, 31, 46, 55, 58], small grants [56, 57] and a university [54]. Five papers made no reference to a funding source [28, 30, 34, 43, 51].

Wenke [35] identified measures to promote the financial sustainability of the Health Practitioner Research Fellow role, including “Additional research and administrative funding, the use of technology and team based research” (p. 667). Proctor [54] identified the reliance on a single funding source for subsidising the TRIPLE programme as a threat to its sustainability. Similarly, Robinson [11] identified the 5-year funding cycles for Applied Research Collaborations as a factor undermining their sustainability. Gerrish [49] identified time limited funding of the Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC) as a prompt to focus on “securing research grants and capitalising upon a range of opportunities for knowledge translation within a broader agenda focused on quality, innovation, productivity and prevention” (p. 223–224).

Moore [43] described potential mechanisms to ensure the sustainability of the Practicing Knowledge Translation programme, such as delivering online courses. Finally, Young [37] identified the adaptability of the AH-TRIP programme as a key sustainability feature, along with the establishment of a dedicated working group to conduct a formal sustainability assessment. Few papers explicitly described factors or mechanisms to sustain the efforts and outcomes of the knowledge translation capability building programmes. Hitch [29] described the development of a senior leadership position for knowledge translation in occupational therapy in which key deliverables included the development of documentation and resources to support the ongoing sustainability of the position. Similarly, Sinfield [52] described the development of a bank of resources housed on the CLAHRC website, a “train the trainer” model, and e-learning resources to sustain the capability building efforts.

Eleven programmes were guided by a knowledge translation theory or framework such as the Knowledge to Action (KTA) cycle [26, 27, 43, 44, 58, 59], the Dobbins (2002) Framework [40] and the National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools to frame the education programme [41, 42]. Martin [31] used the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) to guide the implementation of the programme. Mickan [32] referred to the use of knowledge management theory, the linkage and exchange model and the social change framework to inform the functions of the knowledge brokers implemented in their programme. Morrow [6] used the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) and behaviour change theory in the development of their intervention. Mosson [56] used the principles of training transfer to inform their education programme.

Programme implementation level of influence and manager engagement

Programmes were categorised according to their implementation at four structural levels of impact in accordance with Cooke’s [22] framework: individual, team, organisational and supra-organisational. See Table 3 for the levels, definitions and citations. Interventions implemented at the individual or team level aimed to build the knowledge translation capacity of individuals and teams through increased knowledge, self-efficacy, research culture and engagement in knowledge translation. Programmes targeted at individuals included university courses [31, 51, 60], workplace training [44, 54, 57] and fellowship programmes [30]. Several programmes delivered training in a team environment to facilitate potential collaboration [26, 27, 36, 37, 39, 53]. Some larger-scale training interventions were implemented at an organisational level. For example, one study delivered workshops to teams across 35 units from different organisations [56]. Interventions aimed at this level most commonly took the form of dedicated research support roles, embedded within health organisations. These roles often involved educating interested health professionals through various means [29, 32, 41, 42, 45], strengthening research culture [45], engaging stakeholders [32], developing partnerships or collaborations [35, 45] and building research infrastructure [29, 35, 41, 42]. Other organisational strategies included secondments which provided health service staff with protected time to engage in knowledge translation endeavours [50]. Strategies implemented at the supra-organisational-level generally aimed to improve healthcare practice through collaboration, and strategies typically involved multifaceted initiatives of cross-organisational research collaborations such as CLAHRCs [48, 52] and Research Translation Centres [11]. In other cases, clinical-academic collaborations were fostered through a competitive funding initiative [33] and the development of communities of practice [58].

First line (middle) or senior executive managers were described as integral to many of the programmes to develop knowledge translation capacity and capability across the four levels of impact. Manager involvement was enacted in several ways: managers as programme participants [29, 38, 41,42,43,44, 46, 48, 49, 51,52,53,54, 56, 57, 60]; engagement or overt support of managers [26, 27, 32, 40, 50, 55]; letter of intent or support for team member participation [34, 39, 44]; managers were involved in the delivery of the strategy [38, 48] and co-design of the programme with managers [58]. In one programme, the manager needed to sign off to demonstrate their overt support for and was subsequently involved in the programme [56]. Several papers mentioned the presence and/or need for manager involvement or support in the outcomes or findings [11, 31, 35, 45, 49, 55]. One paper, describing a programme targeting doctors working in the family medicine context, did not explicitly refer to the involvement of managers; however, it did note that doctors in these settings also filled a managerial role [59].

Programme and model evaluation

Evaluation methods

Twenty-seven programmes underwent some degree of formal evaluation, with defined aims and methods described to varying levels of detail in the papers (Table 4). The outcomes of the remaining seven programmes were described as the authors’ general reflections or learnings from some informal or not otherwise-described evaluation process [34, 38, 45, 49, 51, 52, 58]. Data collection methods used in the evaluations described included surveys [26,27,28,29,30,31, 39, 40, 43, 44, 46, 53,54,55,56,57, 59, 60], individual interviews [6, 11, 28, 30,31,32, 35,36,37, 43, 46,47,48, 50, 54, 56, 57], author reflections [26, 27, 34, 38, 45, 49, 51,52,53, 58,59,60], focus groups [26, 27, 30, 31, 35, 41, 44, 50], documentary analysis [28, 40, 42, 48, 55], attendance records [42, 43, 55], measured research outputs [29, 38] and observed changes to clinical guidelines, practice, or networks [38, 39, 55]. Twenty-four programmes were evaluated using multiple data collection methods.

Outcomes measured or described

Although the outcomes measured and reported varied significantly across the 34 programmes, all papers reported positive outcomes and the achievement of the programme objectives to varying extents. Outcome measures utilised in programme evaluations included participant self-reported improvements in knowledge, skills or confidence (etc.) [6, 26, 27, 29, 31, 33, 34, 39, 41, 43, 44, 46, 50, 53, 54, 56, 57], participant satisfaction with or perceived quality of the programme [6, 28, 34, 37, 46, 47, 52,53,54, 56, 57, 59, 60], participant experiences of programme [11, 29, 30, 32, 34, 36, 44, 46, 48, 50, 51], participant self-reported changes to clinical or knowledge translation practice, guidelines or organisation policy (etc.) [27, 31, 33, 41, 43, 44, 47, 56, 57], barriers and enablers of knowledge translation [11, 26, 27, 35, 36, 39, 45, 50, 55], attendance or engagement with programme [28, 37, 39, 40, 42, 43, 55], perceptions of organisational culture [26, 27, 35, 41, 48,49,50], observed or reported behaviour change (e.g. knowledge translation leadership development or changed clinical practice) [35, 38, 39, 49, 55], milestone achievement (e.g. implementation plans completed) [33, 37, 39, 53], new or expanded partnerships, collaborations, or networks [28, 29, 33, 35], traditional research outputs (e.g. papers, conference presentations, grants) [29, 33] and interest in programme or new applications [60].

Strengths and limitations of evaluation studies

Programme evaluations were strengthened by the inclusion of multiple outcome measures. Studies which incorporated multiple outcome measures often used a combination of self-reported outcomes or experience and more objective outcomes or observations such as milestone achievement [29, 36, 37, 39, 53, 55], observed behaviour change [35, 39, 44, 55] new or strengthened collaborations [29, 33], research outputs [29], observed skill development [59] and programme cost [36, 37]. Ten programme evaluations were informed by existing theoretical models including the Kirkpatrick Model [6, 46, 53, 54, 56, 57], the TDF [26, 27], the CFIR [31], Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services framework [44], reflexive thematic analysis against knowledge brokering theory and practice [32] and the Canadian Academy of Health Sciences’ Framework for Evaluation and Payback Framework [33]. One programme used both the Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, Maintenance (RE-AIM) and TDF in two separate evaluations of the same programme [36, 37]. Evaluations tended to focus on short-term outcomes [6, 33, 46, 53, 59, 60]; however, there were examples of longer-term programme evaluation, as defined by data collected beyond 12-month post-programme delivery [26,27,28,29, 31, 32, 35,36,37,38,39, 41, 42, 44, 47, 49, 57].

There were some common limitations in the programme evaluations identified across the included papers. No studies measured health outcomes as a result of the programme. Several focused on only one outcome such as programme attendance or engagement [40], research outputs [38], perceptions or experiences of the programme [30, 32, 51], participant self-reported changes in knowledge, skills, confidence [6], barriers and enablers of knowledge translation [45], satisfaction or perceived quality of the programme [52]. One study did not identify any specific measurable outcomes [58]. Other commonly identified limitations were the use of self-reported outcomes only [26, 27, 33, 48, 50, 56, 57], and outcomes reported or measured among self-selected and likely more engaged and invested participants [11, 26, 28, 39, 44, 46, 47, 57]. Papers commonly described small sample sizes or low response rates in evaluations requiring participant involvement (e.g. surveys, interviews) [6, 11, 29,30,31,32, 37, 46, 47, 53]. Studies were often conducted at a single site or with a single cohort [29, 35, 41, 42, 44, 48], limiting the generalisability of the findings. Furthermore, programme evaluations were often limited by the inclusion of programme participants only in the data collection activities (e.g. [11, 26, 31, 36, 37, 47, 53]), i.e. there were no comparisons or controls. However, some programme evaluations engaged a broader range of relevant stakeholders to identify a more diverse range of outcomes at various levels of impact [28, 34, 35, 41, 42, 48, 50]. A notable example is the case study evaluation undertaken by Wenke [35] in which the relevant healthcare service executive director, incumbent holding the implementation support role, and six clinicians who had worked with the incumbent, participated in the evaluation. Similarly, Haynes’ [28] evaluation involved the chief investigators, members of the research network, and policy, practitioner and researcher partners.

There was an apparent lack of attention to the sustainability of programmes in the evaluations and there was only one evaluation which incorporated economic evaluation as part of the programme [37]. Further, measures of objective or observed behaviour change were included in only a few evaluations, including increased clinician engagement in research [35], the attraction of research funding [38], clinical service changes [35] and sustained knowledge translation practices post-programme participation [39, 44, 50, 55].

Although some studies investigated perceptions of organisational impacts such as research or knowledge translation culture [26, 27, 41, 42, 48,49,50] and barriers and enablers of knowledge translation [11, 26, 27, 35, 36, 39, 45, 50, 55], only one programme evaluation utilised a validated tool or approach to measuring organisational factors (the TDF) [26, 27]. Few studies used validated data collection tools to measure any types of outcomes [26, 27, 44, 54]. Only one evaluation included a control group in the data collection and analysis [31]. One study evaluated participant satisfaction and engagement with the programme only [60]. Poorly described or informal evaluation methods were identified in several papers [34, 38, 40, 45, 49, 51, 52, 55, 58, 59].

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first scoping review of programmes designed to build capacity and capability for knowledge translation in healthcare settings. We sought to identify the models and approaches to building knowledge translation capability in healthcare settings, including the types of strategies used, the underpinning theories, funding sources, sustainability features, mechanisms of evaluation and the outcomes measured and reported. Our findings indicate that this is an area of increasing research interest and practice internationally [3]. We identified numerous types of strategies in place to promote knowledge translation capability in health settings, and an array of outcomes measured and reported in evaluations of these programmes.

Education was the most frequently described strategy and was delivered most often within health settings, followed by universities, and other organisations. Education was often delivered in concert with other strategies including implementation support roles, co-design of capability-building initiatives, funding for knowledge translation and strategic research-practice partnerships and collaboratives. This suggests that education is the cornerstone of knowledge translation capability building. It also points to the widespread recognition of the complexity of knowledge translation in practice [62,63,64,65] and the need to take a multifaceted approach to developing health professionals’ and healthcare service capacity and capability.

Programmes were implemented at four structural levels of impact [22]. Translating research in health practice requires the active involvement of and collaboration with various stakeholders [66, 67]; therefore, programmes aimed at team, organisational and supra-organisational level are more likely to see meaningful and sustained outcomes and impacts beyond the life of the programme and evaluation [4, 5, 68]. Social and experiential pedagogies [69], and mentoring featured prominently in the capability building programmes analysed as part of this review. Although didactic learning featured in many of the programmes in our review, this approach was complemented by either collaborative or experiential learning, or both. In contrast, Juckett et al. [4] found didactic coursework was a prominent feature within academic initiatives that aimed build advance knowledge translation practice.

Many programmes appeared to be dependent on time-limited funding or non-recurrent grants (government or philanthropic), with some only funded for discrete periods of time [36, 37, 45]. There were no references to ongoing funding sources to enable programme development, delivery or evaluation. This lack of certainty around funding and resourcing may undermine the continuity, quality, sustainability and impact of knowledge translation capability building programmes. Knowledge translation capacity-building programme leads can optimise the opportunities for ongoing funding by producing high-quality evaluations demonstrating impact on practice, and the alignment of their programmes with broader health policy agendas (e.g. promoting equity and quality in healthcare, and reducing inefficiencies) [70].

Although not always described explicitly as sustainability measures, there was evidence of these integrated in numerous programmes to maintain and further spread the impact of the programmes within the setting [24]. One of the sustainability features was the active engagement of managers in many of the programmes described in this review [26, 27, 29, 32, 34, 38,39,40, 42,43,44, 46, 48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58, 60]. This reinforces the recognition of the role of middle managers in supporting and mediating health practice changes, and in building capacity and positive attitudes toward knowledge translation within their teams [71, 72]. For organisations in which health professionals work independently, such as in medical and family practices, the middle manager role may be filled by the health professionals themselves [59]; therefore, strategies tailored to these settings and individuals are needed.

Both the content and implementation of several programmes were informed by knowledge translation theories or frameworks, which suggests a level of integrity in these programmes and the commitment of those developing and delivering the programmes to the theory and practices they seek to promote in participants. Furthermore, utilising evidence-informed implementation may promote the sustainability of the intervention in practice, and sustained outcomes and impact of the programme [73]. Several programmes were co-designed with end-users [26, 37, 38, 47, 57, 58], which not only increases the suitability of the programme to the local context but also increases a sense of ownership of the capability building programmes and strategies, and the potential to enhance sustainability [68, 74]. Other benefits of the early involvement of end-users in the development of capacity-building programmes in health settings include the integration of features and complexities reflective of the healthcare environment, and improved adoption and adaptation [75, 76]. This accentuates the need for future knowledge translation capacity and capability building programmes to be co-designed with end-users.

Overall, we found that programmes’ targeted levels of impact rarely corresponded with the outcomes measured in their evaluation. This highlights the need to develop standardised or at least streamlined frameworks that can be adopted by those leading the delivery or evaluation of programmes, to facilitate the planning and execution of appropriate evaluation. That is, if the programme targets the individual level, outcomes measured should relate to individuals (for example, self-reported improvements in knowledge, attitudes, satisfaction with programme) and if targeting the organisational level, outcomes related to research culture, the advent of new partnerships with research institutions or changes to organisational practice and policy, for example, should be measured. Similarly, programme evaluations rarely made clear the timeframe over which the outcomes were expected and measured. In one exemplary case, Young et al. [37] presented a programme logic which identified the programme components including inputs, activities and participant types, and linked these to the anticipated short-, medium- and long-term outcomes. The evaluation was then designed around these components and in reference to the RE-AIM framework. This points to the utility of programme logic in designing programmes and their evaluations.

Only one study, also Young et al.’s [37], explicitly referred to the absence of a dedicated evaluation budget as a limitation; however, this was likely the case for all programme delivery and evaluation teams, contributing to many of the identified limitations in the evaluations. Therefore, a standardised, theory-informed evaluation framework is needed to enable robust and consistent evaluation of multiple types of short-, medium- and longer-term outcomes, which correspond with the various levels of impacts [4, 6, 31, 32, 56]. This will enable more strategic programme implementation, make effective use of limited resources and provide for more illuminating programme evaluations to guide future capability building practice.

Strengths and methodological limitations

This scoping review is strengthened by the systematic methods used. The involvement of a large team of researchers, with different levels of research and knowledge translation experience, representing different perspectives including experienced academic and knowledge translation researchers, those involved in developing and delivering knowledge translation capability building programmes, early career researchers and health professionals working in healthcare settings, in every stage of the review, enhanced the rigour of the study and the strength of our findings.

The main limitation of this review is the nature of the review topic and the existence of many synonyms and homonyms for several key concepts. The sheer breadth of relevant literature means the search strategy may not have included every relevant term, and therefore, may not have captured all eligible studies. Although formal quality assessment was not conducted, the limitations identified in the included papers and the absence of a formal evaluation in seven programmes indicate a generally low level of quality of the studies. This underlines the need for caution when interpreting and utilising the findings of this review. The settings in which the programmes were delivered were primarily larger health organisations with tiered managerial structures. Therefore, the findings, particularly as they relate to the role of and implications for middle managers, may not apply to contexts within which health professionals work independently (for example, physicians and family medicine doctors).

The databases searched did not include education research-specific databases, which may also have inadvertently excluded relevant papers from the search yield. The review of the programmes is limited to the strategies, characteristics, evaluation methods and outcomes as they were reported in the papers. It is likely that some of the papers did not include the details of all programme components and elements. This review is also limited by heterogeneity of the programmes with respect to the strategies described, outcomes measured, and findings reported. This diversity precluded the identification and application of a proxy measure of impact and subsequent comparison of the programmes. Nonetheless, as this scoping review aimed to map the programmes and strategies documented, the characteristics of the programmes, outcomes measured and reported, we were able to address the review questions.

Implications for practice and future research

The review findings reinforce the need for knowledge translation capacity and capability building programmes to comprise multiple strategies working in concert to affect impact at the individual, team, organisational and supra-organisational levels. Practice-based pedagogies, collaborative learning and manager engagement are central to programmes to promote favourable outcomes. The review also highlighted several gaps in the literature. First, there is a need for more rigorous programme evaluations, which requires dedicated funding or resourcing. This could be supported by future research such as a focused systematic review on the outcomes and impacts of individual strategies (e.g. education), or structural levels of impact (e.g. team-level), to identify the most appropriate outcome measures and data collection methods. This will aid in simplifying programme evaluations and promote consistency across programmes. Furthermore, subsequent research could be undertaken to identify the presence and utility of any conceptual frameworks to guide capacity and capability building programme development, implementation and evaluation.

Conclusion

There are a range of programmes that aim to develop knowledge translation capacity and capability in healthcare settings. Programmes tend to be multifaceted with education as the cornerstone, facilitate experiential and collaborative learning and target different levels of impact: individual, team, organisational and supra-organisational. All papers described successful outcomes and the achievement of programme objectives to some degree. Features to promote sustainability are evident; however, the sustainability of programmes and their outcomes and impacts may be threatened by the lack of commitment to long-term funding, and resourcing for rigorous programme evaluation. Indeed, the outcomes and impacts of these programmes are unclear and unable to be compared due to the often poorly described and widely inconsistent methods and outcome measures used to evaluate these programmes. Future research is required to inform the development of theory-informed frameworks to guide the use of methods and outcome measures to evaluate the short-, medium- and longer-term outcomes at the different structural levels, with a view to measuring objectively, the impacts on practice, policy and health outcomes in the longer term.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Abbreviations

- AHP:

-

Allied health professional

- CFIR:

-

Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research

- CLAHRC:

-

Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care

- COG:

-

Clinical outcome group

- EBP:

-

Evidence-based practice

- EIDM:

-

Evidence-informed decision making

- HIC:

-

High-income countries

- JBI:

-

Joanna Briggs Institute

- KB:

-

Knowledge broker

- KT:

-

Knowledge translation

- KTA:

-

Knowledge to Action

- NHS:

-

National Health Service

- NIHR:

-

National Institute for Health Research

- OECD:

-

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

- OT:

-

Occupational therapist

- PCC:

-

Population, concept, and context

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses

- PRISMA-ScR:

-

PRISMA extension for scoping reviews

- RCB:

-

Research capacity building

- RE-AIM:

-

Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, Maintenance

- TDF:

-

Theoretical Domains Framework

References

Albers B, Metz A, Burke K, Bührmann L, Bartley L, Driessen P, et al. Implementation support skills: Findings from a systematic integrative review. Res Soc Work Pract. 2021;31(2):147–70.

Bornbaum CC, Kornas K, Peirson L, Rosella LC. Exploring the function and effectiveness of knowledge brokers as facilitators of knowledge translation in health-related settings: a systematic review and thematic analysis. Impl Sci. 2015;10:1–12.

Metz A, Albers B, Burke K, Bartley L, Louison L, Ward C, et al. Implementation practice in human service systems: Understanding the principles and competencies of professionals who support implementation. Hum Serv Organ Manag Leadersh Gov. 2021;45(3):238–59.

Juckett LA, Bunger AC, McNett MM, Robinson ML, Tucker SJ. Leveraging academic initiatives to advance implementation practice: a scoping review of capacity building interventions. Impl Sci. 2022;17(1):1–14.

Braithwaite J, Ludlow K, Testa L, Herkes J, Augustsson H, Lamprell G, et al. Built to last? The sustainability of healthcare system improvements, programmes and interventions: a systematic integrative review. BMJ Open. 2020;10(6):e036453.

Morrow A, Chan P, Tiernan G, Steinberg J, Debono D, Wolfenden L, et al. Building capacity from within: qualitative evaluation of a training program aimed at upskilling healthcare workers in delivering an evidence-based implementation approach. Transl Behav Med. 2022;12(1):ibab094.

Brownson RC, Jacob RR, Carothers BJ, Chambers DA, Colditz GA, Emmons KM, et al. Building the next generation of researchers: mentored training in dissemination and implementation science. Acad Med. 2021;96(1):86.

Davis R, D’Lima D. Building capacity in dissemination and implementation science: a systematic review of the academic literature on teaching and training initiatives. Impl Sci. 2020;15:1–26.

King OA, Sayner AM, Beauchamp A, West E, Aras D, Hitch D, et al. Research translation mentoring for emerging clinician researchers in rural and regional health settings: a qualitative study. BMC Med Educ. 2023;23(1):817.

O’Byrne L, Smith S. Models to enhance research capacity and capability in clinical nurses: a narrative review. JCN. 2011;20(9–10):1365–71.

Robinson T, Skouteris H, Burns P, Melder A, Bailey C, Croft C, et al. Flipping the paradigm: a qualitative exploration of research translation centres in the United Kingdom and Australia. Health Res Policy Syst. 2020;18(1):1–14.

Coates D, Mickan S. Challenges and enablers of the embedded researcher model. J Health Organ Manag. 2020;34(7):743–64.

Sarkies MN, Robins LM, Jepson M, Williams CM, Taylor NF, O’Brien L, et al. Effectiveness of knowledge brokering and recommendation dissemination for influencing healthcare resource allocation decisions: A cluster randomised controlled implementation trial. PLoS Med. 2021;18(10):e1003833.

Howlett O, O’Brien C, Gardner M, Neilson C. The use of mentoring for knowledge translation by allied health: a scoping review. JBI Evid Implement. 2022;20(4):250–61.

King O, West E, Lee S, Glenister K, Quilliam C, Wong Shee A, et al. Research education and training for nurses and allied health professionals: a systematic scoping review. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22(1):385.

Yoong SL, Bolsewicz K, Reilly K, Williams C, Wolfenden L, Grady A, et al. Describing the evidence-base for research engagement by health care providers and health care organisations: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2023;23(1):1–20.

Damarell RA, Tieman JJ. How do clinicians learn about knowledge translation? An investigation of current web-based learning opportunities. JMIR Med Educ. 2017;3(2):e7825.

Munn Z, Peters MD, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18:1–7.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern. 2018;169(7):467–73.

The World Bank. Data for High income Om, Upper middle income. Data for High income, OECD members, Upper middle income https://data.worldbank.org/?locations=XD-OE-XT2021N.D. Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/?locations=XD-OE-XT. Accessed 10 June 2023.

Salloum RG, LeLaurin JH, Nakkash R, Akl EA, Parascandola M, Ricciardone MD, et al. Developing Capacity in Dissemination and Implementation Research in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: Evaluation of a Training Workshop. Implement Res Appl. 2022;2(4):1–10.

Cooke J. A framework to evaluate research capacity building in health care. BMC Fam Pract. 2005;6:1–11.

Cooke J. Building Research Capacity for Impact in Applied Health Services Research Partnerships Comment on" Experience of Health Leadership in Partnering With University-Based Researchers in Canada–A Call to" Re-imagine" Research". IJHPM. 2021;10(2):93.

Bodkin A, Hakimi S. Sustainable by design: a systematic review of factors for health promotion program sustainability. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1–16.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group* t. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern. 2009;151(4):264–9.

Bennett S, Whitehead M, Eames S, Fleming J, Low S, Caldwell E. Building capacity for knowledge translation in occupational therapy: learning through participatory action research. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16(1):1–11.

Eames S, Bennett S, Whitehead M, Fleming J, Low SO, Mickan S, et al. A pre-post evaluation of a knowledge translation capacity-building intervention. Aust Occup Ther J. 2018;65(6):479–93.

Haynes A, Rowbotham S, Grunseit A, Bohn-Goldbaum E, Slaytor E, Wilson A, et al. Knowledge mobilisation in practice: an evaluation of the Australian Prevention Partnership Centre. Health Res Policy Syst. 2020;18(1):1–17.

Hitch D, Lhuede K, Vernon L, Pepin G, Stagnitti K. Longitudinal evaluation of a knowledge translation role in occupational therapy. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19:1–12.

Lizarondo L, McArthur A, Lockwood C, Munn Z. Facilitation of evidence implementation within a clinical fellowship program: a mixed methods study. JBI Evid Implement. 2021;19(2):130–41.

Martin E, Fisher O, Merlo G, Zardo P, Barrimore SE, Rowland J, et al. Impact of a health services innovation university program in a major public hospital and health service: a mixed methods evaluation. Impl Sci Commun. 2022;3(1):1–9.

Mickan S, Wenke R, Weir K, Bialocerkowski A, Noble C. Using knowledge brokering activities to promote allied health clinicians’ engagement in research: a qualitative exploration. BMJ Open. 2022;12(4):e060456.

Mosedale A, Geelhoed E, Zurynski Y, Robinson S, Chai K, Hendrie D. An impact review of a Western Australian research translation program. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(3):e0265394.

Wales S, Kelly M, Wilson V, Crisp J. Enhancing transformational facilitation skills for nurses seeking to support practice innovation. Contemp Nurse. 2013;44(2):178–88.

Wenke RJ, Tynan A, Scott A, Mickan S. Effects and mechanisms of an allied health research position in a Queensland regional and rural health service: a descriptive case study. Aust Health Rev. 2018;42(6):667–75.

Wilkinson SA, Hickman I, Cameron A, Young A, Olenski S, BPhty PM, et al. ‘It seems like common sense now’: experiences of allied health clinicians participating in a knowledge translation telementoring program. JBI Evid Implement. 2022;20(3):189–98.

Young AM, Cameron A, Meloncelli N, Barrimore SE, Campbell K, Wilkinson S, et al. Developing a knowledge translation program for health practitioners: Allied Health Translating Research into Practice. Front Health Serv. 2023;3.

Wolfenden L, Yoong SL, Williams CM, Grimshaw J, Durrheim DN, Gillham K, et al. Embedding researchers in health service organizations improves research translation and health service performance: the Australian Hunter New England Population Health example. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;85:3–11.

Black AT, Steinberg M, Chisholm AE, Coldwell K, Hoens AM, Koh JC, et al. Building capacity for implementation—the KT Challenge. Implement Sci Commun. 2021;2:1–7.

Dobbins M, Robeson P, Ciliska D, Hanna S, Cameron R, O’Mara L, et al. A description of a knowledge broker role implemented as part of a randomized controlled trial evaluating three knowledge translation strategies. Impl Sci. 2009;4(1):1–9.

Dobbins M, Traynor RL, Workentine S, Yousefi-Nooraie R, Yost J. Impact of an organization-wide knowledge translation strategy to support evidence-informed public health decision making. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:1–15.

Dobbins M, Greco L, Yost J, Traynor R, Decorby-Watson K, Yousefi-Nooraie R. A description of a tailored knowledge translation intervention delivered by knowledge brokers within public health departments in Canada. Health Res Policy Syst. 2019;17(1):1–8.

Moore JE, Rashid S, Park JS, Khan S, Straus SE. Longitudinal evaluation of a course to build core competencies in implementation practice. Impl Sci. 2018;13:1–13.

Park JS, Moore JE, Sayal R, Holmes BJ, Scarrow G, Graham ID, et al. Evaluation of the “Foundations in Knowledge Translation” training initiative: preparing end users to practice KT. Impl Sci. 2018;13(1):1–13.

Plamondon K, Ronquillo C, Axen L, Black A, Cummings L, Chakraborty B. Bridging research and practice through the Nursing Research Facilitator Program in British Columbia. Nurs Leadersh. 2013;26(4):32–43.

Provvidenza C, Townley A, Wincentak J, Peacocke S, Kingsnorth S. Building knowledge translation competency in a community-based hospital: a practice-informed curriculum for healthcare providers, researchers, and leadership. Impl Sci. 2020;15(1):1–12.

Thomson D, Brooks S, Nuspl M, Hartling L. Programme theory development and formative evaluation of a provincial knowledge translation unit. Health Res Policy Syst. 2019;17:1–9.

Cooke J, Ariss S, Smith C, Read J. On-going collaborative priority-setting for research activity: a method of capacity building to reduce the research-practice translational gap. Health Res Policy Syst. 2015;13:1–11.

Gerrish K. Tapping the potential of the National Institute for Health Research Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC) to develop research capacity and capability in nursing. J Res Nurs. 2010;15(3):215–25.

Gerrish K, Piercy H. Capacity development for knowledge translation: evaluation of an experiential approach through secondment opportunities. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2014;11(3):209–16.

Greenhalgh T, Russell J. Promoting the skills of knowledge translation in an online master of science course in primary health care. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2006;26(2):100–8.

Sinfield P, Donoghue K, Horobin A, Anderson ES. Placing interprofessional learning at the heart of improving practice: the activities and achievements of CLAHRC in Leicestershire. Northamptonshire and Rutland Qual Prim Care. 2012;20(3):191–8.

Astorino JA, Kerch S, Pratt-Chapman ML. Building implementation science capacity among practitioners of cancer control: development of a pilot training curriculum. Cancer Causes Control. 2022;33(9):1181–91.

Proctor E, Ramsey AT, Brown MT, Malone S, Hooley C, McKay V. Training in Implementation Practice Leadership (TRIPLE): evaluation of a novel practice change strategy in behavioral health organizations. Impl Sci. 2019;14:1–11.

Christensen C, Wessells D, Byars M, Marrie J, Coffman S, Gates E, et al. The impact of a unique knowledge translation programme implemented in a large multisite paediatric hospital. J Eval Clin Pract. 2017;23(2):344–53.

Mosson R, Augustsson H, Bäck A, Åhström M, von Thiele SU, Richter A, et al. Building implementation capacity (BIC): a longitudinal mixed methods evaluation of a team intervention. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19:1–12.

Richter A, Lornudd C, von Thiele SU, Lundmark R, Mosson R, Skoger UE, et al. Evaluation of iLead, a generic implementation leadership intervention: mixed-method preintervention–postintervention design. BMJ Open. 2020;10(1):e033227.

Davies S, Herbert P, Wales A, Ritchie K, Wilson S, Dobie L, et al. Knowledge into action–supporting the implementation of evidence into practice in Scotland. Health Info Libr J. 2017;34(1):74–85.

Wahabi HA, Al-Ansary LA. Innovative teaching methods for capacity building in knowledge translation. BMC Med Educ. 2011;11(1):1–10.

Davis R, Mittman B, Boyton M, Keohane A, Goulding L, Sandall J, et al. Developing implementation research capacity: longitudinal evaluation of the King’s College London Implementation Science Masterclass, 2014–2019. Impl Sci Commun. 2020;1(1):1–13.

Yardley S, Teunissen PW, Dornan T. Experiential learning: AMEE guide No. 63. Med Teach. 2012;34(2):e102–15.

Braithwaite J, Churruca K, Long JC, Ellis LA, Herkes J. When complexity science meets implementation science: a theoretical and empirical analysis of systems change. BMC Med. 2018;16:1–14.

Greenhalgh T, Wieringa S. Is it time to drop the ‘knowledge translation’metaphor? A critical literature review. J R Soc Med. 2011;104(12):501–9.

Greenhalgh T, Papoutsi C. Spreading and scaling up innovation and improvement. BMJ. 2019;365.

Mallidou AA, Atherton P, Chan L, Frisch N, Glegg S, Scarrow G. Core knowledge translation competencies: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:1–15.

Albers B, Metz A, Burke K. Implementation support practitioners–a proposal for consolidating a diverse evidence base. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20:1–10.

Glegg SM, Jenkins E, Kothari A. How the study of networks informs knowledge translation and implementation: a scoping review. Impl Sci. 2019;14:1–27.

Rapport F, Smith J, Hutchinson K, Clay-Williams R, Churruca K, Bierbaum M, et al. Too much theory and not enough practice? The challenge of implementation science application in healthcare practice. J Eval Clin Pract. 2022;28(6):991–1002.

Taylor DC, Hamdy H. Adult learning theories: implications for learning and teaching in medical education: AMEE Guide No. 83. Med Teach. 2013;35(11):e1561–72.

World Health Organisation. Global Action Plan for Healthy Lives and Well-being for All (SDG3 GAP). https://www.who.int/initiatives/sdg3-global-action-plan: World Health Organisation; 2019.

Birken S, Clary A, Tabriz AA, Turner K, Meza R, Zizzi A, et al. Middle managers’ role in implementing evidence-based practices in healthcare: a systematic review. Impl Sci. 2018;13:1–14.

Meza RD, Triplett NS, Woodard GS, Martin P, Khairuzzaman AN, Jamora G, et al. The relationship between first-level leadership and inner-context and implementation outcomes in behavioral health: a scoping review. Impl Sci. 2021;16(1):1–21.

Lennox L, Maher L, Reed J. Navigating the sustainability landscape: a systematic review of sustainability approaches in healthcare. Impl Sci. 2018;13(1):1–17.

Goodyear-Smith F, Jackson C, Greenhalgh T. Co-design and implementation research: challenges and solutions for ethics committees. BMC Med Ethics. 2015;16(1):1–5.

Ward ME, De Brún A, Beirne D, Conway C, Cunningham U, English A, et al. Using co-design to develop a collective leadership intervention for healthcare teams to improve safety culture. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(6):1182.

Johannessen T, Ree E, Strømme T, Aase I, Bal R, Wiig S. Designing and pilot testing of a leadership intervention to improve quality and safety in nursing homes and home care (the SAFE-LEAD intervention). BMJ Open. 2019;9(6):e027790.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge and sincerely thank Fiona Russell and Jill Stephens, Research Librarians at Deakin University for their invaluable contributions to developing the literature search strategy, conducting the scoping and initial literature searches and retrieval process. We also thank Professor Suzanne Robinson for her contribution to the development of the review concept and protocol.

Funding

The DELIVER research program was supported by a Commonwealth funded MRFF Rapid Applied Research Translation Grant (RARUR000072). All Deakin Rural Health staff are supported by the Rural Health Multidisciplinary Training program, funded by the Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. Deakin Rural Health, Western Alliance, and Anna Peeters's National Health and Medical Research Council Investigator Grant contributed to funding the publication costs for this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

OAK, EW, AWS, HB, LA, AP, CH, WP, SR, KM, MC and MM were jointly involved in developing and designing the study aims, questions and protocol. OAK, EW, MPa, MPi, HB, AWS, WP, CH, MC, LA, MM, AS and KM were involved in reviewing and screening abstracts and full texts for inclusion, and extraction of data from included papers. OAK, EW, MPi, CH, WP and AWS contributed to the data analysis. OAK and EW drafted the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed, read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Authors’ information

Olivia A. King (PhD) is Manager of Research Capability Building for Western Alliance, Adjunct Research Associate with the Monash Centre for Scholarship in Health Education, and Affiliate Senior Lecturer with Deakin Rural School.

Emma West is a research assistant at Deakin University and Program Officer, Research Capability Building for Western Alliance.

Laura Alston (PhD) is Director of Research, Colac Area Health and Senior Research Fellow Deakin University (Deakin Rural Heath).

Hannah Beks (MPH) is a Research Fellow with Deakin Rural Health and funded by the Rural Health Multidisciplinary Training program (Australian Government).

Michele Callisaya (PhD) is a Senior Research Fellow at the National Centre for Healthy Ageing and Monash University.

Catherine E. Huggins (PhD) is Program manager for DELIVER (MRFF Rapid Applied Research Translation project).

Margaret Murray (BSc Hons) is an Associate Research Fellow with Deakin Rural Health, at Deakin University.

Kevin Mc Namara (PhD) is Deputy Director, Research at Deakin Rural Health (School of Medicine) and Stream Leader, Economics of Pharmacy at Deakin Health Economics (Centre for Population Health Research).

Michael Pang is a senior Physiotherapist at Grampians Health.

Warren Payne (PhD) is Executive Director, Western Alliance.

Anna Peeters (PhD) is Director, Institute for Health Transformation and Principal Research Translation Investigator, Western Alliance.

Mia Pithie is a Physiotherapist at Grampians Health.

Alesha M. Sayner is Allied Health Research and Knowledge Translation Lead at Grampians Health and Affiliate Researcher with Deakin University (Deakin Rural Heath).

Anna Wong Shee (PhD) is Associate Professor Allied Health at Grampians Health and Deakin University (Deakin Rural Heath).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to partcipate

No ethical approval was required to conduct this scoping review of the peer-reviewed and grey literature.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Scoping Review Protocol.

Additional file 2.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) Checklist.

Additional file 3.

Search Strategy.

Additional file 4.

Grey Literature Searches.

Additional file 5.

Excluded Studies.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

King, O., West, E., Alston, L. et al. Models and approaches for building knowledge translation capacity and capability in health services: a scoping review. Implementation Sci 19, 7 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-024-01336-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-024-01336-0