Abstract

Background

Research capacity building (RCB) initiatives have gained steady momentum in health settings across the globe to reduce the gap between research evidence and health practice and policy. RCB strategies are typically multidimensional, comprising several initiatives targeted at different levels within health organisations. Research education and training is a mainstay strategy targeted at the individual level and yet, the evidence for research education in health settings is unclear. This review scopes the literature on research education programs for nurses and allied health professionals, delivered and evaluated in healthcare settings in high-income countries.

Methods

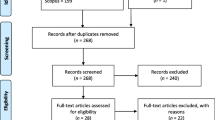

The review was conducted systematically in accordance with the Joanna Briggs Institute scoping review methodology. Eleven academic databases and numerous grey literature platforms were searched. Data were extracted from the included full texts in accordance with the aims of the scoping review. A narrative approach was used to synthesise findings. Program characteristics, approaches to program evaluation and the outcomes reported were extracted and summarised.

Results

Database searches for peer-reviewed and grey literature yielded 12,457 unique records. Following abstract and title screening, 207 full texts were reviewed. Of these, 60 records were included. Nine additional records were identified on forward and backward citation searching for the included records, resulting in a total of 69 papers describing 68 research education programs.

Research education programs were implemented in fourteen different high-income countries over five decades. Programs were multifaceted, often encompassed experiential learning, with half including a mentoring component. Outcome measures largely reflected lower levels of Barr and colleagues’ modified Kirkpatrick educational outcomes typology (e.g., satisfaction, improved research knowledge and confidence), with few evaluated objectively using traditional research milestones (e.g., protocol completion, manuscript preparation, poster, conference presentation). Few programs were evaluated using organisational and practice outcomes. Overall, evaluation methods were poorly described.

Conclusion

Research education remains a key strategy to build research capacity for nurses and allied health professionals working in healthcare settings. Evaluation of research education programs needs to be rigorous and, although targeted at the individual, must consider longer-term and broader organisation-level outcomes and impacts. Examining this is critical to improving clinician-led health research and the translation of research into clinical practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The translation of research evidence into health practice and policy relies on healthcare organisations and systems having sufficient research capacity and capability [1,2,3]. Health organisation executives and policymakers globally, recognise the need to invest in research capacity building (RCB) initiatives and interventions that are delivered in healthcare settings [2,3,4]. RCB strategies encompass a range of initiatives designed to promote individual, team and organisation research skills, competence and to influence attitudes towards research [2, 5,6,7]. Initiatives designed to build individual and organisational research capacity may include education and training programs, funding for embedded researchers (e.g., fellowships, scholarships) and other research support roles (e.g., research librarians, knowledge-brokers), strategic collaborations with academic partners and developing research infrastructure [2, 6, 8]. RCB strategies often comprise a combination of the aforementioned approaches [8] and notably, research education and training programs are a sustaining feature of many [2, 3, 6, 8,9,10,11]. This is likely related to the insufficient coverage of research in undergraduate health curricula and the need for supplementary education to fill research knowledge and skill gaps, particularly for non-medically trained healthcare professionals. Medically trained healthcare professionals typically have a greater inclination toward and engagement in research than their nurse and allied health counterparts [4, 8, 12, 13]. Given that nursing and allied health form the majority of the health workforce [14, 15], there is increasing interest in RCB strategies that target nurses and allied health professionals to enhance the delivery of evidence-informed care across all healthcare settings and services [8, 16,17,18]. Allied health comprises a range of autonomous healthcare professions including physiotherapy, social work, podiatry, and occupational therapy [16].

This review was commissioned by an academic health science centre in Australia, to inform the research education and training component of its health organisation RCB strategy. Given the typically multidimensional nature of RCB strategies, their functions and impacts at the various levels are inextricably related [2, 5]. This makes the discernment between research education and training interventions and other elements of strategies a fraught endeavour. For example, embedded researchers may form part of a broader organisational RCB strategy, and in the scope of their work, may perform an ad hoc education function (e.g., through their interactions with novice researchers) [11, 19]. Aligning with the purpose of this work, this review defines research education and training programs as organised initiatives or interventions that are either discrete (e.g., standalone workshops or research days) or longer in their duration (e.g., research courses or a series of workshops or lectures) wherein curriculum is developed and shared with multiple individuals or participants, with a view to develop and apply research skills [2, 5]. Healthcare settings are considered those wherein the provision of healthcare is considered core business (e.g., hospitals, community-based health services, cancer care services, family medicine clinics) and is therefore the setting in which research evidence needs to be applied or translated to reduce the gap between research knowledge and practice [2, 20].

An initial search of Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Joanna Briggs Institute’s Evidence Synthesis, PROSPERO, and Google Scholar for reviews of research education and training programs delivered in health settings, yielded no existing or planned reviews. On further cursory review of the RCB and research education literature, and concomitant discussions with four content experts (i.e., educators, academic and clinician researchers concerned with research capacity building), it became apparent that research education programs take different forms, occur in pockets within health organisations across health districts and regions, are not always formally evaluated, and often fail to account for adult learning principles and theories. The decision to conduct a scoping review, rather than a conventional systematic review, was based on three key factors: 1) the heterogeneity evident in research education program characteristics; 2) the absence of an existing synthesis of evidence for research education programs delivered in health settings [5]; and 3) the need to identify the gaps in knowledge about these programs.

This systematic scoping review sought to scope the research education and training programs delivered to nurses and allied health professionals working in health settings and the evidence supporting these approaches. The specific review objectives were to describe the:

-

1.

Types of research education programs delivered in health settings in high-income countries

-

2.

Theoretical or pedagogical principles that underly the programs

-

3.

Approaches to research education program evaluation

-

4.

Types of outcomes reported

Methods

This review used the Joanna Briggs Institute’s (JBI) scoping review methodology. As per the JBI methodology, search terms were developed for Population, Concept and Context (PCC). The review question, objectives, inclusion/exclusion criteria and search strategies were developed and documented in advance (Additional File 1 Scoping Review Protocol). The review is reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) extension for scoping reviews (Additional File 2 PRISMA-ScR checklist [21]).

Search strategy

The researchers identified a set of key papers based on their knowledge of contemporary research education programs and in consultation with four content experts from two high-income countries. They used these papers to identify the key search terms. In consultation with the research librarians (SH and HS, see acknowledgements), the research team conducted preliminary scoping searches to test the search terms and strategy (between 3 March – 10 March 2022). These searches informed decisions about final search terms. A tailored search strategy was developed for each academic database (Additional file 3 Search Strategy).

Academic databases searched included PubMed, Ovid MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, VOCEDPlus, PEDro, Scopus, ERIC, Informit Health Database, JBI, and Google Scholar. Selected grey literature platforms as determined by our knowledge of relevant websites and organisations, were searched. Where larger search yields were observed (e.g., via Google and Google Scholar), the first 250 items were reviewed, only (Additional file 4 Grey literature search). The final research database searches were conducted between 12 and 15 March 2022 by a researcher with extensive systematic literature searching experience (Author 2) in consultation with a research librarian. Grey literature searches were conducted on 17 March 2022. Searches of the reference lists of included records and forward citation searches were undertaken.

Inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria

Literature was selected according to defined inclusion and exclusion criteria developed using the PCC framework (see Table 1). Research education or capacity building programs delivered to qualified health professionals, working in health settings (excluding programs delivered as part of tertiary study) in high-income countries (HIC) as defined by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), were included [22]. The decision to include studies published in HICs only was made with a view to introduce a level of homogeneity around the broader resource contexts of the study populations [23, 24]. No date limits applied, and all types of literature published up to 17 March 2022 were included. Literature published in English only was included, due to resource limitations.

Study selection, quality appraisal and data extraction

Citations were imported into Covidence (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia) for screening. Titles and abstracts were independently screened by two reviewers initially, with conflicts resolved by a third (independent) reviewer. Similarly, full texts were reviewed by two researchers and the reasons for exclusion were noted (Additional file 5 Excluded studies). Data was extracted from the included texts by five researchers. Formal quality appraisal is not typically undertaken as part of scoping review methodology and was not undertaken for the papers included in this review [25].

Data extracted were tabulated and results were synthesized using a descriptive approach guided by the review objectives as per a scoping review methodology. Outcomes measured and reported in the papers were mapped to the modified Kirkpatrick’s educational outcomes typology [26, 27]. Recognising the complex interactions between individuals, research education programs, organisational and other factors, and the various outcomes produced [2], the modified Kirkpatrick’s typology gives rise to the identification of outcome measures at multiple levels or within these inter-related domains [26].

Results

Of the 207 citations considered for full text screening, 60 met the inclusion criteria and nine additional papers were located through a citation search of the initial set (Fig. 1 PRISMA Flow Diagram) [28].

Research education program characteristics

When, where and to whom research education programs were delivered

A total of 69 papers, describing 68 research education and training programs were reviewed. The implementation of the programs spanned five decades, with almost half (n = 33) implemented in the most recent decade. Research education programs were delivered in the United States of America (n = 22), Australia (n = 20), the United Kingdom (n = 9), Canada (n = 5), Denmark (n = 2), Qatar (n = 2), and one each in Argentina, Finland, Japan, Italy, Singapore, Sweden, Spain, and The Netherlands. The geographical distribution of programs by country is presented in Fig. 2. Research education programs were targeted and delivered to different healthcare professional groups. Programs were delivered most frequently to nurses and midwives (n = 35), then mixed professional groups (n = 18), allied health (n = 13), and pharmacists (n = 2). The characteristics of included programs are provided in Table 2.

How research education programs were formatted and delivered

Research education programs were delivered in several different formats and over different types of durations. Some were delivered as standalone single study days, workshops or sessions [29,30,31,32,33,34], and others as a series of several short sessions or workshops [35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45]. The majority of papers described integrated research education courses of either a short duration, (i.e., one to 4 months) [46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65], medium duration (i.e., five to 11 months) [9, 66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76], or longer-duration (i.e., 1 year or longer) [77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94].

Programs almost always included a didactic element (e.g., lectures, seminars), delivered by an experienced academic or clinician-researcher (researcher with a primary healthcare qualification; [95]) or an individual with content expertise (e.g., biostatistician [48], librarian [33, 57, 66], ethics committee member [57] or data manager [42]). Most of the programs were multifaceted and included a mix of didactic teaching as well as either group discussion, online teaching (e.g., teleconferences or modules), or the practical application of theoretical principles between education sessions. Several were described as single mode research education programs (e.g., seminars, lectures, or online modules only) [29,30,31, 33, 37,38,39, 46, 48, 49, 53,54,55, 87]. Timing was described as an important consideration in several papers, with an emphasis on minimising impact on participants’ working day or clinical duties. For example, by holding sessions early (8 am) prior to the working day [9, 51] or on weekends [32, 63, 71].

Features and content of research education programs

The curricula or research education content described in the papers reflected the aims of the programs. Program aims were broadly categorised according to the level of intended participants’ research engagement: research use or consumption (n = 28) and research activity (n = 31) [96]. Where the program content focused on searching, retrieving, and appraising research literature, and considering in the context of clinical practice (i.e., evidence-based practice), this was considered engagement at the research user or consumer level. Slightly more programs were concerned with developing research skills to engage in and conduct research activity. These programs included content related to research methods, data collection and analysis techniques, protocol development and ethics application [31, 35, 37, 39, 42, 43, 48, 49, 52, 53, 57, 59, 63, 64, 67, 68, 73, 77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85, 90,91,92]. Seven programs were orientated toward developing participants’ skills for research dissemination, typically writing for publication [9, 32, 33, 47, 51, 74] or preparing research posters and seminars [88]. It was assumed that the participants in the programs concerned with writing for publication had already undertaken a research activity and needed further education and support to formally disseminate their findings. Two programs were specifically focused on developing participants’ skills to complete a systematic review [46, 76]. Three programs included content directly related to implementing research in practice [60, 80, 86].

Fourteen programs required that participants had overt support from their manager to participate (e.g., written approval or direct selection of participants) [46, 51, 58, 62, 75, 79,80,81, 83, 85, 91,92,93,94]. Two papers described participants’ departments being actively supportive of their participation in the research education program [59, 86]. One paper referred to managers’ positive role modelling by engaging in the research education program [39] and another described the criteria used to determine the suitability of participants based on their context (i.e., supportive managers who were interested in research and willing to release participating staff for half day each week) [88]. Five papers described manager or leadership support as being a key enabler to participants engaging in the education program [56, 60, 75, 89, 91] and four papers referred explicitly to the lack of organisational, managerial, or collegial support as key limitations to, or a negative influence on participants’ learning experience [49, 77, 84, 88].

Nine papers described the integration of opportunities to acknowledge the achievements of program participants. Opportunities were described as formal events held at the conclusion of the program to celebrate the participants’ completion [58, 66, 80, 83], recognition via staff communications or at an organisation-wide event [37], opening participants’ project presentations to a wider healthcare organisation audience [92], or by managers providing opportunities for participating staff to present their work to colleagues [81, 82]. One program included the acknowledgment of contact hours for nurse participants to attain continuing professional development points for their professional registration [54] and another referred to participants’ “recognition and exposure” within and beyond their organisation, as a participant-reported benefit (46, e–145).

Theories and pedagogical principles

Understanding how people learn effectively is fundamental to the design of any educational program. Thus, the second aim of this review was to determine what pedagogies (teaching methods) were employed for adult learners undertaking research education and training. Few of the studies (n = 13) included in this review explicitly stated which pedagogical strategies informed the design and delivery of the education programs. However, where possible we extracted pedagogical strategies that appear to be present (see Table 2).

Education programs generally included a mix of active and passive learning strategies. Active learning can be defined as an activity which engages students as participants in the learning process whereas with passive learning, students receive information from the instructor but have little active involvement [97]. Passive forms of learning or didactic approaches that were employed included seminars, lectures, reading, and exams. Five programs were described with respect to the didactic learning component only, with no reference or implication of any underlying pedagogy or learning theory [39, 45, 48, 49, 53].

Commonly, education programs included some form of experiential learning. Experiential learning, or “learning by doing” is a type of active learning whereby students apply knowledge to real-world situations and then reflect on the process and experience [98]. Examples of experiential learning described in the education programs include simulations, role-play, preparation of research protocols, grant proposals, manuscripts, and appraisal of research. Lack of experiential learning, or “practical experience”, was described as a limitation in one paper [38]. Quizzes were utilised in two programs [42, 66] to reinforce participants’ learning.

Social cognitive theories of learning, such as self-efficacy theory [99], were explicitly mentioned in seven studies [31, 47, 54, 56, 61, 71, 72]. Self-efficacy theory posits that a person’s belief in their capabilities provide the foundation for performance and accomplishment. If a person has low self-efficacy (little belief in their capabilities) and fear related to the task at hand, they will likely avoid that task for fear of failure. Education programs using a self-efficacy framework focused on increasing participants self-efficacy through coaching, support, social modelling, and mastery experiences. Five studies referred to Roger’s Diffusion of Innovation theory [37, 50, 60, 68, 71], which posits that identifying and working with highly motivated individuals is an efficient way to promote the adoption of new behaviours and practices more widely [8].

Two studies were informed by the Advancing Research and Clinical practice through close Collaboration (ARCC) Model which is based on cognitive-behavioural theory and control theory, and therefore designed to address barriers to desired behaviours and practice [65, 100]. Other programs described drew on the transtheoretical model of organisational change [62], Donald Ely’s conditions for change [37], the knowledge to action framework [52] and the Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (PARiHS) Framework [72].

Mentoring was a feature of more than half of the programs (n = 37). This is where novice researchers were paired with an experienced researcher, typically to support their application and practice of the knowledge gleaned through their education or training [101]. In three papers describing programs that did not include mentoring, this was identified as a critical element for future research education programs [37, 78, 92]. Several evaluations of programs that included mentoring illustrated that it was required throughout the life of the program and beyond [9, 32, 67, 68, 73, 81, 84]. Harding et al. [46] found that mentors as well as mentees, benefited from the research education program, in terms of their own learning and motivation.

Social theories of learning, or collaborative learning approaches, were also frequently utilised (n = 40). Collaborative learning approaches are based on the notion that learning is a social activity at its core, shaped by context and community. Such approaches promote socialisation and require learners to collaborate as a group to solve problems, complete tasks, or understand new concepts. Collaborative approaches utilised included journal clubs [38, 50, 54, 69, 70, 87], writing groups [32, 51], classroom discussions [33, 36, 72, 76, 80, 94], interactive group workshops or activities [29, 31, 46, 47, 56, 75, 82, 84, 86, 93], and development of team research projects [78, 79]. These approaches were often reported to enhance cultural support with participants networking, sharing resources, and celebrating successes together. One program employed a self-guided learning approach through the use of computer-based learning modules [55].

Approaches to program evaluation

Less than half of the included papers accurately and comprehensively described the methodology and methods used to evaluate the research education program [9, 30, 38, 46, 54,55,56, 60,61,62,63, 65, 69,70,71, 75, 77, 79, 82, 84,85,86, 89, 100, 102]. The remaining papers either referred to the data collection techniques used without describing the overarching approach or methodology. Therefore, in Table 3 rather than referring to the approach to program evaluation as quantitative, qualitative or mixed methods, reference is made to the data collection techniques (e.g., surveys, interviews, facilitator reflections, audit of research outputs).

Most programs were evaluated using surveys (n = 51), some of these in combination with other outcome measures. More than half of the program evaluations (n = 38) used pre- and post-intervention surveys. Other evaluation methods included interviews, focus groups, attendance rates, and outcomes audits (e.g., ethics applications, manuscripts submitted for peer review or published, grant applications, grants awarded, or adherence to evidence-based guidelines). Twelve evaluation studies included a control group [36, 38, 51, 60, 65, 68,69,70, 77, 79, 86, 100]. Three evaluations were informal and did not explicitly draw on evaluation data but rather on general feedback, authors’ own reflections and observations, including observed research progress [35, 37, 94]. Evaluation of the longer-term outcomes were described in seven papers, where surveys were undertaken or outcomes were otherwise measured between one and 5 years after the programs were completed [44, 51, 76, 84, 85, 89, 93].

Outcomes measured and described

Program outcome measures were mapped to Barr et al.’s modified Kirkpatrick educational outcomes typology [27]. The typology categorises educational outcomes reported according to their level of impact. The outcomes levels range from individual learner-level outcomes through to the impact of educational program on their organisation and healthcare consumer outcomes. See Table 4 below for descriptions of the outcome levels and the corresponding citations.

Almost all program evaluations included a mix of outcome measure types or levels. In addition to the modified Kirkpatrick level outcomes, other types of outcomes and impacts were measured and reported. Program participant engagement was measured and reported with reference to interest and uptake, attendance, and drop-out rates in five evaluations [48, 54, 74, 78, 87]. Twelve program evaluations explored participants’ experiences or perspectives of barriers to engaging in research in their health setting [34, 36, 49, 56, 71, 77, 81, 82, 84, 86, 88, 89] and four evaluations included program cost calculations [51, 60, 83, 90]. One evaluation measured group cohesion, participant (nurse) productivity and nursing staff retention [100].

Programs that were evaluated over a longer period demonstrated a high success rate with respect to manuscript publication [34, 51, 76], longer term development of research skills, experience, and engagement [44, 84, 89], and highlighted the value of mentoring to participants’ enduring engagement with research and to their development of research confidence and leadership skills [84]. One evaluation study included administrative leaders [89], one included training participants’ managers [93], however none included senior executives or healthcare consumers.

Discussion

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first systematic scoping review of the research education literature. The findings of the review support existing evidence of the continued relevance of research education and training to RCB endeavours [2, 16]. Indeed, research education appears to be a mainstay RCB strategy over the last five decades. This review sought to explore the features or characteristics of research education and training programs delivered to nurses and allied health professionals working in health settings in HICs, the pedagogical principles or learning theories underpinning the programs, how programs were evaluated, and the types of outcomes reported.

Common features and approaches to the delivery of research education were identified. Some common pedagogical features of research education programs: multifaceted delivery to allow for flexibility in engaging with the program and content [5, 103], experiential learning [2, 103] and social or collaborative learning principles [103]. These underpinning principles were implied more frequently than they were explicitly stated. The integration of mentoring to reinforce the knowledge gleaned through research education programs appears to be a critical element and a key component of contemporary research education and capacity building [2, 3, 104].

This review also highlights some differences in the programs, particularly in terms of duration, which varied from single sessions or workshops to three-year programs. The curricula or educational content tended to reflect the aims of the programs which mapped to two different levels of engagement with research: research use or consumption and research activity. Some programs were specifically focused on advanced research skills, namely writing for publication, which is a particularly challenging aspect of the research process for clinicians [7, 51].

Findings indicate that organisational context and support are pivotal to the cultivation of and completion of research activity [2, 6, 7, 49, 77, 84, 88, 105]. Although this review focused specifically on papers describing research education programs targeting individual-level research capacity, there were several organisation-related factors that were integrated into the programs. Middle or executive level manager support for program participants was evident in numerous papers either through explicit support or permission, or positive role modelling. This resonates with the findings of existing evidence related to organisational factors enabling research [7, 106, 107]. Schmidt and colleagues [106] have previously highlighted a lack of managerial support for research training participants and their projects, as a factor influencing withdrawal. Several programs incorporated events or other opportunities for participants to present their work or to be otherwise recognised [37, 46, 54, 66, 80,81,82,83]. This facilitated organisation-level acknowledgement and celebration of individuals’ research activity and achievement, reinforcing organisational support for research [2].

This scoping review highlights some evidence of the impact of research education beyond the individual participants, and on their colleagues and organisations more broadly. This broader impact can be attributed to participants actively sharing their new knowledge and skills with their colleagues and teams [108]. Roger’s Diffusion of Innovation Theory can also underpin RCB strategies that are targeted at the individual level and explain how and why they have a broader impact on organisational research capacity and culture [104].

Research education program outcome measures tend to reflect lower levels of Kirkpatrick’s modified typology, with comparatively few studies reporting organisation-level impacts and none reporting health consumer outcomes. Although it is recognised that measuring and demonstrating direct links between RCB initiatives and health consumer outcomes is difficult [109], RCB initiatives including research training typically aim to promote the delivery of evidence-informed care, which in turn improves health consumer outcomes [110]. Some program evaluations included self-reported measures by participants that did not engage in the research education program, providing for comparisons between groups. Senior and executive managers, and healthcare consumers, however, were not involved in any evaluations reported. This limits knowledge of the outcomes and impacts beyond the individual participant level. Moreover, the program evaluation methods were generally poorly described. This is somewhat paradoxical, given the subject matter, however it is not a problem unique to research education and capacity building. Indeed poor evaluation is a widespread problem evident in multiple key healthcare areas such as Aboriginal Health in Australia [111] supportive care services for vulnerable populations [112], and in continuing education for healthcare professionals [113]. Factors contributing to poor program evaluation likely include time constraints, inaccessible data, and inadequate evaluation capacity and skills, as described in other scoping reviews of health and health professions education programs [111,112,113].

Although it is encouraging to see broadening interest in RCB initiatives for the nursing and allied health professions including research education, investment in rigorous, carefully planned, broadly targeted and long-term evaluation is required. This will ensure that research education programs maximise the outcomes for individuals and organisations and the most crucial impact on health consumer outcomes can be measured.

Strengths and methodological limitations

The strengths of this scoping review are the adherence to an established and systematic approach and the wide and comprehensive search including 11 research databases, multiple grey literature databases and search engines. The methodological and content expertise within the research team, including expertise in scoping review, systematic review, realist review methodologies and research education and capacity building strategies strengthened the rigour of the review. Moreover, the consultation with content experts during the development of the search strategy ensured the review was well-informed and shaped to meet the needs of those concerned with RCB.

Nonetheless, this review is limited by several factors. Research education, training, and RCB more broadly are poorly defined concepts [2], as such, it is acknowledged that the search strategy was developed in such a way that it may not have resulted in the retrieval of all relevant literature. This is acceptable, given the scoping review aimed to provide an overview of the breadth and depth of the literature and used content expertise to balance the comprehensiveness of the review with the capacity to answer research questions [114]. It is, however, recommended that the findings of this review inform a more focused and systematic review of the literature.

It is well-established that research education and training alone, do not sufficiently influence research capacity and capability at an individual or organisational level [1, 7]. Indeed, barriers to nurse and allied health-led research include time constraints, demanding clinical workloads, enduring workforce shortages, a lack of organisational support and research culture, funding, and inadequate research knowledge and skills, persist [7, 12, 39, 47, 115]. These factors were not analysed as part of the review. The explicit focus on research education meant that some RCB strategies with education as a component may have been missed.

The authorship team were situated in Australia, with limited knowledge of other, complementary search engines internationally and lacked the resources to execute extensive international grey literature searches. These limited grey literature searches introduce a level of publication bias. Publications in languages other than English were excluded for reasons related to feasibility and limited resourcing. Through engagement with content experts early in the review, it was noted that many education programs are not formally documented, evaluated, or published in peer-reviewed or grey literature and therefore not accessible to others outside the organisation. This means that the review of published literature may not entirely represent research education programs in health settings.

Conclusion

Research education is a cornerstone RCB strategy for nurses and allied health professionals working in health settings. Education is typically aimed at enhancing individual clinician-level RCB however, there is some evidence that the outcomes of individual-level research education can influence organisational research capacity and culture. Moreover, strategies targeted at the organisational level can be integrated into research education programs. Mentoring, experiential, and collaborative learning have gained recognition as key features of research education programs and facilitate the application of new knowledge and skills in practice. Evaluation continues to focus on lower levels of educational impact or traditional research outputs; there is need for greater attention to organisational culture, longer-term capacity building outcomes and health consumer impacts. Approaches to the evaluation of research education programs should incorporate the experiences and perspectives of managers, executives, health consumers and other stakeholders concerned with research capacity and the delivery of evidence-informed care. This will ensure that RCB strategies and initiatives with greater impact at the individual and organisational level can be supported and that the impact of such initiatives can be measured at the population health level.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Abbreviations

- EBP:

-

Evidence based practice

- JBI:

-

Joanna Briggs Institute

- HIC:

-

High-income countries

- OECD:

-

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

- PCC:

-

Population, Concept and Context

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses

- PRISMA-ScR:

-

PRISMA extension for scoping reviews

- RCB:

-

Research capacity building

- RCT:

-

Randomised control trial

References

Pickstone C, Nancarrow S, Cooke J, Vernon W, Mountain G, Boyce RA, et al. Building research capacity in the allied health professions. Evidence & Policy. 2008;4(1):53–68.

Cooke J, Gardois P, Booth A. Uncovering the mechanisms of research capacity development in health and social care: a realist synthesis. Health Res Policy Syst. 2018;16(1):93.

Slade SC, Philip K, Morris ME. Frameworks for embedding a research culture in allied health practice: a rapid review. Health Res Policy Syst. 2018;16(1):29.

Gill SD, Gwini SM, Otmar R, Lane SE, Quirk F, Fuscaldo G. Assessing research capacity in Victoria's south-west health service providers. Aust J Rural Health. 2019;27(6):505–13.

Mazmanian PE, Coe AB, Evans JA, Longo DR, Wright BA. Are researcher development interventions, alone or in any combination, effective in improving researcher behavior? A systematic review Eval Health Prof. 2014;37(1):114–39.

Cooke J. A framework to evaluate research capacity building in health care. BMC Fam Pract. 2005;6:44.

Golenko X, Pager S, Holden L. A thematic analysis of the role of the organisation in building allied health research capacity: a senior managers' perspective. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:276.

Mickan S, Wenke R, Weir K, Bialocerkowski A, Noble C. Strategies for research engagement of clinicians in allied health (STRETCH): a mixed methods research protocol. BMJ Open. 2017;7(9):e014876.

Harvey D, Barker R, Tynan E. Writing a manuscript for publication: An action research study with allied health practitioners. Australian & New Zealand Association for Health Professional Educators (ANZAHPE). 2020:1–16.

Schmidt D, Reyment J, Webster E, Kirby S, Lyle D. Workplace-based health research training: a qualitative study of perceived needs in a rural setting. Health Res Policy Syst. 2020;18(1):67.

Noble C, Billett SR, Phang DTY, Sharma S, Hashem F, Rogers GD. Supporting Resident Research Learning in the Workplace: A Rapid Realist Review. Acad Med. 2018;93(11):1732–40.

Luckson M, Duncan F, Rajai A, Haigh C. Exploring the research culture of nurses and allied health professionals (AHPs) in a research-focused and a non-research-focused healthcare organisation in the UK. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27(7–8):e1462–e76.

Trusson D, Rowley E, Bramley L. A mixed-methods study of challenges and benefits of clinical academic careers for nurses, midwives and allied health professionals. BMJ Open. 2019;9(10):e030595.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Health Workforce. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-health/health-workforce; 2020.

NHS Digital. NHS Workforce Statistics - October 2021: NHS; 2022 [3 Feb 2022]. Available from: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/nhs-workforce-statistics/october-2021.

Matus J, Walker A, Mickan S. Research capacity building frameworks for allied health professionals - a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):716.

Gimeno H, Alderson L, Waite G, Chugh D, O'Connor G, Pepper L, et al. Frontline Allied Health Professionals in a Tertiary Children’s Hospital: Moving Forward Research Capacity, Culture and Engagement. J Pract-Based Learn Health Soc Care. 2021;9(1):29–49.

Chen Q, Sun M, Tang S, Castro AR. Research capacity in nursing: a concept analysis based on a scoping review. BMJ Open. 2019;9(11):e032356.

Wenke R, Ward, E. C., Hickman, I., Hulcombe, J., Phillips, R., Mickan, S.,. Allied health research positions: a qualitative evaluation of their impact. Health Res Policy Syst 2017;15(1):6.

Mickan S, Coates D. Embedded researchers in Australia: Survey of profile and experience across medical, nursing and midwifery and allied health disciplines. J Clin Nurs. 2020.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.

The World Bank. Data for High income, OECD members, Upper middle income https://data.worldbank.org/?locations=XD-OE-XT2021 [Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/?locations=XD-OE-XT.

Ekeroma AJ, Kenealy T, Shulruf B, Nosa V, Hill A. Building Capacity for Research and Audit: Outcomes of a Training Workshop for Pacific Physicians and Nurses. J Educ Train Stud. 2015;3(4):179–92.

Dodani S, Songer T, Ahmed Z, Laporte RE. Building research capacity in developing countries: cost-effectiveness of an epidemiology course taught by traditional and video-teleconferencing methods in Pakistan. Telemed J E Health. 2012;18(8):621–8.

Munn Z, Peters MD, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):1–7.

Curran V, Reid A, Reis P, Doucet S, Price S, Alcock L, et al. The use of information and communications technologies in the delivery of interprofessional education: A review of evaluation outcome levels. J Interprofessional Care. 2015;29(6):541–50.

Barr H, Koppel I, Reeves S, Hammick M, Freeth DS. Effective Interprofessional Education: Argument, Assumption and Evidence (Promoting Partnership for Health). Chichester: Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated; 2005.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

Bott MT. Reading research: a review of a research critical appraisal workshop. CANNT Journal= Journal ACITN. 2000;10(3):52–4.

Hicks C. Bridging the gap between research and practice: an assessment of the value of a study day in developing critical research reading skills in midwives. Midwifery. 1994;10(1):18–25.

O'Halloran VE, Pollock SE, Gottlieb T, Schwartz F. Improving self-efficacy in nursing research. Clin Nurse Spec. 1996;10(2):83–7.

Horstman P, Theeke L. Using a professional writing retreat to enhance professional publications, presentations, and research development with staff nurses. J Nurses Staff Dev. 2012;28(2):66–8.

Doyle JD, Harvey SA. Teaching the publishing process to researchers and other potential authors in a hospital system. J Hosp Librariansh. 2005;5(1):63–70.

Rutledge DN, Mooney K, Grant M, Eaton L. Implementation and Refinement of a Research Utilization Course for Oncology Nurses. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2004;31(1).

Gething L, Leelarthaepin B, Burr G, Sommerville A. Fostering nursing research among nurse clinicians in an Australian area health service. J Contin Educ Nurs. 2001;32(5):228–37.

Hundley V, Milne J, Leighton-Beck L, Graham W, Fitzmaurice A. Raising research awareness among midwives and nurses: does it work? J Adv Nurs. 2000;31(1):78–88.

Bamberg J, Perlesz A, McKenzie P, Read S. Utilising implementation science in building research and evaluation capacity in community health. Aust J Prim Health. 2010;16(4):276–83.

Corchon S, Portillo MC, Watson R, Saracibar M. Nursing research capacity building in a Spanish hospital: an intervention study. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20(17–18):2479–89.

Edward KL, Mills C. A hospital nursing research enhancement model. J Contin Educ Nurs. 2013;44(10):447–54.

Land LM, Ward S, Taylor S. Developing critical appraisal skills amongst staff in a hospital trust. Nurs Educ Pract. 2002;2(3):176–80.

Mulhall A, Le May A, Alexander C. Research based nursing practice–an evaluation of an educational programme. Nurse Educ Today. 2000;20(6):435–42.

Allen S, Boase S, Piggott J, Leishman H, Herring W, Gunnell C, et al. Innovation in clinical research workshops. Pract Nurs. 2010;21(12):645–9.

Elkassem W, Pallivalapila A, Al Hail M, McHattie L, Diack L, Stewart D. Advancing the pharmacy practice research agenda: views and experiences of pharmacists in Qatar. Int J Clin Pharm. 2013;35(5):692–6.

Famure O, Batoy B, Minkovich M, Liyanage I, Kim SJ. Evaluation of a professional development course on research methods for healthcare professionals. Healthcare Management Forum. 2021;34(3):186–92.

Munro E, Tacchi P, Trembath L. A baseline for nurse education on research. Nurs Times. 2016;112(19):12–4.

Harding KE, Stephens D, Taylor NF, Chu E, Wilby A. Development and evaluation of an allied health research training scheme. J Allied Health. 2010;39(4):e143–8.

Shatzer M, Wolf GA, Hravnak M, Haugh A, Kikutu J, Hoffmann RL. A curriculum designed to decrease barriers related to scholarly writing by staff nurses. J Nurs Adm. 2010;40(9):392–8.

Wojtecki CA, Wade MJ, Pato MT. Teaching interested clinicians how to develop research projects. Acad Psychiatry. 2007;31(2):168–70.

Berthelsen CB, Hølge-Hazelton B. An evaluation of orthopaedic nurses' participation in an educational intervention promoting research usage–a triangulation convergence model. J Clin Nurs. 2016;25(5–6):846–55.

Chan EY, Glass GF, Phang KN. Evaluation of a Hospital-Based Nursing Research and Evidence-Based Practice Mentorship Program on Improving Nurses' Knowledge, Attitudes, and Evidence-Based Practice. J Contin Educ Nurs. 2020;51(1):46–52.

Duncanson K, Webster EL, Schmidt DD. Impact of a remotely delivered, writing for publication program on publication outcomes of novice researchers. Rural Remote Health. 2018;18(2):4468.

Fry M, Dombkins A. Interventions to support and develop clinician-researcher leadership in one health district. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2017;30(6):528–38.

McNab M, Berry A, Skapetis T. The potential of a lecture series in changing intent and experience among health professionals to conduct research in a large hospital: a retrospective pre-post design. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):124.

Wilson M, Ice S, Nakashima CY, Cox LA, Morse EC, Philip G, et al. Striving for evidence-based practice innovations through a hybrid model journal club: A pilot study. Nurse Educ Today. 2015;35(5):657–62.

Hart P, Eaton L, Buckner M, Morrow BN, Barrett DT, Fraser DD, et al. Effectiveness of a computer-based educational program on nurses' knowledge, attitude, and skill level related to evidence-based practice. Worldviews Evid-Based Nurs. 2008;5(2):75–84.

Mickan S, Hilder J, Wenke R, Thomas R. The impact of a small-group educational intervention for allied health professionals to enhance evidence-based practice: mixed methods evaluation. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):1–10.

Mathers S, Abel R, Chesson R. Developing research skills for clinical governance: a report of a trust/university provided short course. Clinical Governance: An International Journal; 2004.

Milne DJ, Krishnasamy M, Johnston L, Aranda S. Promoting evidence-based care through a clinical research fellowship programme. J Clin Nurs. 2007;16(9):1629–39.

Murphy SL, Kalpakjian CZ, Mullan PB, Clauw DJ. Development and evaluation of the University of Michigan’s Practice-Oriented Research Training (PORT) program. Am J Occup Ther. 2010;64(5):796–803.

Pennington L, Roddam H, Burton C, Russell I, Russell D. Promoting research use in speech and language therapy: a cluster randomized controlled trial to compare the clinical effectiveness and costs of two training strategies. Clin Rehabil. 2005;19(4):387–97.

Swenson-Britt E, Reineck C. Research education for clinical nurses: a pilot study to determine research self-efficacy in critical care nurses. J Contin Educ Nurs. 2009;40(10):454–61.

Varnell G, Haas B, Duke G, Hudson K. Effect of an educational intervention on attitudes toward and implementation of evidence-based practice. Worldviews Evid-Based Nurs. 2008;5(4):172–81.

Awaisu A, Kheir N, Alrowashdeh HA, Allouch SN, Jebara T, Zaidan M, et al. Impact of a pharmacy practice research capacity-building programme on improving the research abilities of pharmacists at two specialised tertiary care hospitals in Qatar: a preliminary study. J Pharm Health Serv Res. 2015;6(3):155–64.

Johnson F, Black AT, Koh JC. Practice-based research program promotes dietitians' participation in research. Can J Diet Pract Res. 2016;77(1):43–6.

Saunders H, Vehviläinen-Julkunen K, Stevens KR. Effectiveness of an education intervention to strengthen nurses’ readiness for evidence-based practice: A single-blind randomized controlled study. Appl Nurs Res. 2016;31:175–85.

Carey MG, Trout DR, Qualls BW. Hospital-Based Research Internship for Nurses: The Value of Academic Librarians as Cofaculty. J Nurses Prof Dev. 2019;35(6):344–50.

Donley E, Moon F. Building Social Work Research Capacity in a Busy Metropolitan Hospital. Res Soc Work Pract. 2021;31(1):101–7.

Gardner A, Smyth W, Renison B, Cann T, Vicary M. Supporting rural and remote area nurses to utilise and conduct research: an intervention study. Collegian. 2012;19(2):97–105.

Wenke RJ, Thomas R, Hughes I, Mickan S. The effectiveness and feasibility of TREAT (Tailoring Research Evidence and Theory) journal clubs in allied health: a randomised controlled trial. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18(1):104.

Lizarondo LM, Grimmer-Somers K, Kumar S, Crockett A. Does journal club membership improve research evidence uptake in different allied health disciplines: a pre-post study. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5(1):1–9.

McCluskey A, Lovarini M. Providing education on evidence-based practice improved knowledge but did not change behaviour: a before and after study. BMC Med Educ. 2005;5(1):1–12.

Tilson JK, Mickan S. Promoting physical therapists’ of research evidence to inform clinical practice: part 1-theoretical foundation, evidence, and description of the PEAK program. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14(1):1–8.

Latimer R, Kimbell J. Nursing research fellowship: building nursing research infrastructure in a hospital. J Nurs Adm. 2010;40(2):92–8.

Richardson A, Carrick-Sen D. Writing for publication made easy for nurses: an evaluation. Br J Nurs. 2011;20(12):756–9.

Mudderman J, Nelson-Brantley HV, Wilson-Sands CL, Brahn P, Graves KL. The effect of an evidence-based practice education and mentoring program on increasing knowledge, practice, and attitudes toward evidence-based practice in a rural critical access hospital. J Nurs Adm. 2020;50(5):281–6.

Tsujimoto H, Kataoka Y, Sato Y, Banno M, Tsujino-Tsujimoto E, Sumi Y, et al. A model six-month workshop for developing systematic review protocols at teaching hospitals: action research and scholarly productivity. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(1):1–8.

Adamsen L, Larsen K, Bjerregaard L, Madsen JK. Moving forward in a role as a researcher: the effect of a research method course on nurses' research activity. J Clin Nurs. 2003;12(3):442–50.

Demirdjian G, Rodriguez S, Vassallo JC, Irazola V, Rodriguez J. In-hospital capacity-building in research and management for pediatric professionals. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2017;115(1):58–64.

Holden L, Pager S, Golenko X, Ware RS, Weare R. Evaluating a team-based approach to research capacity building using a matched-pairs study design. BMC Fam Pract. 2012;13:16.

Wells N, Free M, Adams R. Nursing research internship: enhancing evidence-based practice among staff nurses. J Nurs Adm. 2007;37(3):135–43.

Friesen EL, Comino EJ, Reath J, Derrett A, Johnson M, Davies GP, et al. Building research capacity in south-west Sydney through a Primary and Community Health Research Unit. Aust J Prim Health. 2014;20(1):4–8.

Ghirotto L, De Panfilis L, Di Leo S. Health professionals learning qualitative research in their workplace: A focused ethnography. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1).

Mazzella Ebstein AM, Barton-Burke M, Fessele KL. A Model for Building Research Capacity and Infrastructure in Oncology: A Nursing Research Fellowship. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs. 2020;7(4):312–8.

Withington T, Alcorn N, Maybery D, Goodyear M. Building research capacity in clinical practice for social workers: A training and mentorship approach. Adv Ment Health. 2020;18(1):73–90.

Schmidt DD, Webster E, Duncanson K. Building research experience: Impact of a novice researcher development program for rural health workers. Aust J Rural Health. 2019;27(5):392–7.

Landeen J, Kirkpatrick H, Doyle W. The Hope Research Community of Practice: Building Advanced Practice Nurses' Research Capacity. Can J Nurs Res. 2017;49(3):127–36.

Duffy JR, Thompson D, Hobbs T, Niemeyer-Hackett NL, Elpers S. Evidence-based nursing leadership: evaluation of a joint academic-service journal club. J Nurs Adm. 2011;41(10):422–7.

Kajermo KN, Nordstrom G, Krusebrant A, Lutzen K. Nurses' experiences of research utilization within the framework of an educational programme. J Clin Nurs. 2001;10(5):671–81.

Black AT, Balneaves LG, Garossino C, Puyat JH, Qian H. Promoting evidence-based practice through a research training program for point-of-care clinicians. J Nurs Adm. 2015;45(1):14.

Turkel MC, Ferket K, Reidinger G, Beatty DE. Building a nursing research fellowship in a community hospital. Nurs Econ. 2008;26(1):26.

Jansen MW, Hoeijmakers M. A Masterclass to Teach Public Health Professionals to Conduct Practice-Based Research to Promote Evidence-Based Practice. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2013;19(1):83–92.

Mason B, Lambton J, Fernandes R. Supporting clinical nurses through a research fellowship. J Nurs Adm. 2017;47(11):529–31.

Schmidt DD, Kirby S. A modular approach to rural and remote research education: a project report. Rural Remote Health. 2016;16(1):1–9.

Warren JJ, Heermann JA. The research nurse intern program: a model for research dissemination and utilization. J Nurs Adm. 1998;28(11):39–45.

Coates D, Mickan S. The embedded researcher model in Australian healthcare settings: comparison by degree of “embeddedness”. Transl Res. 2020;218:29–42.

Department of Health and Human Services. Victorian allied health research framework. https://www2.health.vic.gov.au/-/media/health/files/collections/research-and-reports/a/allied-health-victorian-research-framework.pdf?la=en&hash=AFA09DBC506626C113AE2679B1AA7098C560BFE4: State of Victoria, Department of Health and Human Services; 2018.

Kolb DA. Experience as the source of learning and development. Upper Sadle River: Prentice Hall; 1984.

Yardley S, Teunissen PW, Dornan T. Experiential learning: AMEE guide No. 63. Med Teach. 2012;34(2):e102–e15.

Bandura A, Walters RH. Social learning theory. Englewood cliffs Prentice Hall. 1977.

Levin RF, Fineout-Overholt E, Melnyk BM, Barnes M, Vetter MJ. Fostering evidence-based practice to improve nurse and cost outcomes in a community health setting: a pilot test of the advancing research and clinical practice through close collaboration model. Nurs Adm Q. 2011;35(1):21–33.

Cooke J, Nancarrow S, Dyas J, Williams M. An evaluation of the 'Designated Research Team' approach to building research capacity in primary care. BMC Fam Pract. 2008;9:37.

Tilson JK, Mickan S, Sum JC, Zibell M, Dylla JM, Howard R. Promoting physical therapists’ use of research evidence to inform clinical practice: part 2-a mixed methods evaluation of the PEAK program. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14(1):1–13.

Taylor DC, Hamdy H. Adult learning theories: implications for learning and teaching in medical education: AMEE Guide No. 83. Med Teach. 2013;35(11):e1561–e72.

Wenke R, Weir, K. A., Noble, C., Mahoney, J., & Mickan, S. Not enough time for research? Use of supported funding to promote allied health research activity. J Multidiscip Healthc 2018;11:269–277.

Ajjawi R, Crampton PE, Rees CE. What really matters for successful research environments? A realist synthesis Med Educ. 2018;52(9):936–50.

Schmidt D, Robinson K, Webster E. Factors influencing attrition from a researcher training program. International Journal for Researcher Development. 2014.

Wenke R, Mickan S. The role and impact of research positions within health care settings in allied health: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16(a):355.

Webster E, Thomas M, Ong N, Cutler L. Rural research capacity building program: capacity building outcomes. Aust J Prim Health. 2011;17(1):107–13.

Jonker L, Fisher SJ, Dagnan D. Patients admitted to more research-active hospitals have more confidence in staff and are better informed about their condition and medication: results from a retrospective cross-sectional study. J Eval Clin Pract. 2020;26(1):203–8.

McKeon S. Strategic Review of Health and Medical Research in Australia: Final. Report. https://apo.org.au/node/33477. 2013.

Beks H, Binder MJ, Kourbelis C, Ewing G, Charles J, Paradies Y, et al. Geographical analysis of evaluated chronic disease programs for Aboriginal and Torres Strait islander people in the Australian primary health care setting: a systematic scoping review. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1–17.

Valaitis RK, Carter N, Lam A, Nicholl J, Feather J, Cleghorn L. Implementation and maintenance of patient navigation programs linking primary care with community-based health and social services: a scoping literature review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):1–14.

Allen LM, Palermo C, Armstrong E, Hay M. Categorising the broad impacts of continuing professional development: a scoping review. Med Educ. 2019;53(11):1087–99.

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):1–9.

Borkowski D, McKinstry C, Cotchett M, Williams C, Haines T. Research culture in allied health: a systematic review. Aust J Prim Health. 2016;22(4):294–303.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge and sincerely thank Sarah Hayman and Helen Skoglund, Research Librarians at Barwon Health for their invaluable contributions to developing the literature search strategy, conducting the scoping and initial literature searches and retrieval process. They also thank the expert panel for their invaluable contributions in shaping the review.

Authors’ information (optional)

Olivia King (PhD) is Manager of Research Capability Building for Western Alliance.

Emma West is a PhD scholarship holder and research assistant at Deakin University and Program Officer, Research Capability Building for Western Alliance.

Sarah Lee is a PhD candidate at the Monash Centre for Scholarship in Health Education at Monash University.

Kristen Glenister (PhD) is a Senior Research Fellow (Rural Chronic Ill Health) for the Department of Rural Health, University of Melbourne and funded by the Rural Health Multidisciplinary Training program (Australian Government).

Claire Quilliam (PhD) is a Rural Nursing and Allied Health Research Fellow at The University of Melbourne and funded by the Rural Health Multidisciplinary Training program (Australian Government).

Anna Wong Shee (PhD) is Associate Professor Allied Health at Grampians Health and Deakin University.

Hannah Beks (MPH) is an Associate Research Fellow with Deakin Rural Health and funded by the Rural Health Multidisciplinary Training program (Australian Government).

Funding

The authors thank Western Alliance for funding the initial stages of this review and co-funding the publication of this paper with Deakin Rural Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The first three authors (OK, EW, SL) conceived the research idea. Five authors (OK, EW, SL, AWS, and HB) contributed to the title and abstract screening, and review of full texts. Five authors (OK, EW, SL, KG and CQ) contributed to the extraction of data from papers. The first author (OK) drafted the manuscript. The last author (HB) provided methodological expertise and guidance. All authors contributed to the development of the manuscript, read, and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Barwon Health’s Research Ethics, Governance and Integrity Office conferred ethics approval for the engagement of the expert panel (Ref. 19/164). Written informed consent was obtained for all expert panel participants. All methods were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

King, O., West, E., Lee, S. et al. Research education and training for nurses and allied health professionals: a systematic scoping review. BMC Med Educ 22, 385 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-022-03406-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-022-03406-7