Abstract

Background

Accumulating evidence suggests that interventions to de-implement low-value services are urgently needed. While medical societies and educational campaigns such as Choosing Wisely have developed several guidelines and recommendations pertaining to low-value care, little is known about interventions that exist to de-implement low-value care in oncology settings. We conducted this review to summarize the literature on interventions to de-implement low-value care in oncology settings.

Methods

We systematically reviewed the published literature in PubMed, Embase, CINAHL Plus, and Scopus from 1 January 1990 to 4 March 2021. We screened the retrieved abstracts for eligibility against inclusion criteria and conducted a full-text review of all eligible studies on de-implementation interventions in cancer care delivery. We used the framework analysis approach to summarize included studies’ key characteristics including design, type of cancer, outcome(s), objective(s), de-implementation interventions description, and determinants of the de-implementation interventions. To extract the data, pairs of authors placed text from included articles into the appropriate cells within our framework. We analyzed extracted data from each cell to describe the studies and findings of de-implementation interventions aiming to reduce low-value cancer care.

Results

Out of 2794 studies, 12 met our inclusion criteria. The studies covered several cancer types, including prostate cancer (n = 5), gastrointestinal cancer (n = 3), lung cancer (n = 2), breast cancer (n = 2), and hematologic cancers (n = 1). Most of the interventions (n = 10) were multifaceted. Auditing and providing feedback, having a clinical champion, educating clinicians through developing and disseminating new guidelines, and developing a decision support tool are the common components of the de-implementation interventions. Six of the de-implementation interventions were effective in reducing low-value care, five studies reported mixed results, and one study showed no difference across intervention arms. Eleven studies aimed to de-implement low-value care by changing providers’ behavior, and 1 de-implementation intervention focused on changing the patients’ behavior. Three studies had little risk of bias, five had moderate, and four had a high risk of bias.

Conclusions

This review demonstrated a paucity of evidence in many areas of the de-implementation of low-value care including lack of studies in active de-implementation (i.e., healthcare organizations initiating de-implementation interventions purposefully aimed at reducing low-value care).

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The National Cancer Institute estimates that the cost of cancer-related medical services and prescription drugs will be over $246 billion by 2030 [1]. One method of controlling cancer care costs without reducing the quality of care is to de-implement low-value services. While there is no universally accepted definition of de-implementation, it is generally defined as reducing, replacing, or stopping (partially or completely) low-value services [2, 3]. The National Academy of Medicine defines a low-value service as one where the potential risk of harm outweighs the potential benefits, wastes patients’ time or money, and does not increase the value of care to the patient [4, 5]. For example, prostate-specific antigen (PSA) screening for average-risk men [6, 7], lung cancer screening for asymptomatic patients [8], and axillary staging and post-lumpectomy radiotherapy in women older than 70 years of age with clinically node-negative, hormone receptor + breast cancer [9] are considered low-value services in cancer care delivery. Given that there are known low-value services in cancer care [10, 11], this presents an important setting to systematically evaluate de-implementation efforts.

Medical societies have developed several guidelines and recommendations pertaining to low-value tests, treatments, and follow-up processes across the cancer care continuum [12,13,14]. However, recent reviews found that a considerable proportion of services that cancer patients receive could still be classified as low-value [15,16,17]. For example, both the American Society for Clinical Oncology and Choosing Wisely Canada [18, 19] recommend not to use imaging in early-stage breast cancer; despite these recommendations, about one-third of early-stage breast cancer patients underwent at least one advanced imaging exam (e.g., bone scan, positron-emission tomography) for staging [20, 21]. While studies were conducted to explore why so few low-value clinical practices are de-implemented [22, 23], available studies have primarily focused on changes in clinicians’ practice patterns over time in response to educational campaigns (e.g., Choosing Wisely [13]), guidelines (e.g., European Society of Medical Oncology guidelines), or dissemination of scientific publications. Additionally, while the impact of patient-level factors on interventions’ sustainability is well studied [24], little is known about how patient-level factors (e.g., preferences) may impact de-implementation interventions. Furthermore, our understanding of current de-implementation interventions in cancer care delivery and determinants (i.e., factors that influence outcomes [25]) of effective de-implementation efforts in cancer care is limited. Understanding current de-implementation efforts in cancer care delivery is important because it helps to scale up the use of de-implementation interventions and accelerate the reduction of low-value cancer care.

To our knowledge, there is no systematic review that explores the current landscape of de-implementation of low-value services in cancer care delivery. We conducted this systematic review to summarize the literature on interventions to de-implement low-value care in cancer care delivery. Specifically, we sought to identify the determinants of and assess the effectiveness of de-implementation interventions in cancer care. Findings from this study are expected to inform the literature about opportunities for additional work (i.e., identifying gaps) and define an agenda for future research.

Methods

We conducted a systematic literature review. We reported the results of the review according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines (Additional file 1) [26]. The study protocol was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) (registration number: CRD42021252482).

Study inclusion and exclusion criteria

To be included in the review, we required articles to focus on a purposeful effort or intervention to de-implement low-value cancer care. We excluded studies on quality improvement interventions without an active de-implementation component. De-implementation was defined as removing, replacing, reducing, and restricting a low-value service [27]. To identify low-value practices, we used recommendations developed by The American Society of Clinical Oncology and Choosing Wisely Canada [10, 11]. Cancer care delivery was defined as a focus on the diagnosis and treatment of cancer, supportive and survivorship care, and cancer prevention. Additionally, studies were required to be peer-reviewed and report the results of an empirical study. The detailed list of inclusion and exclusion criteria can be found in Table 1.

Information sources and search strategy

The literature search strategy was developed by the first author (AA) along with a professional medical research librarian (RC). The search was intentionally broad to minimize the risk of overlooking potentially relevant studies. The search strategy was developed for the concepts of cancer care delivery, low-value care, and de-implementation of cancer-related programs. The search strategies were created using a combination of subject headings and keywords and were used to search PubMed, Embase, CINAHL Plus, and Scopus from 1 January 1990 to 4 March 2021, when all searches were completed. We also manually scanned the citations of included studies for relevant articles in case they were missed during indexing. As we considered only peer-reviewed published studies, gray literature was not included. We applied the Cochrane human studies filter to exclude animal studies and added a systematic review keyword and publication type filter to exclude systematic review articles. The complete strategy for each of the searches can be found in Additional file 2.

Study selection process

Each title and abstract was screened against the eligibility criteria by two investigators. Discrepancies were resolved through discussions between members of each pair and, when necessary, a third team member reviewed the discrepancy until a consensus was reached. To ensure inter-rater reliability of reviews, three iterations of sample reviews were conducted with each person reviewing 50 articles until an average agreement of 83.38% was reached. The full-text articles were screened in the same manner.

Study quality assessment

Two independent authors assessed the quality of included studies using three risk of bias tools (based on studies’ methodology) including (1) National Institutes of Health (NIH) Quality Assessment Tool for the controlled intervention studies; (2) NIH Quality Assessment Tool for the before-after (pre–post) studies with no control group studies, and (3) NIH Quality Assessment Tool for the observational cohort and cross-sectional studies [28]. Disagreements in the risk of bias scoring were resolved by consensus or by discussion with a third author.

Data extraction and analysis

We did not conduct a meta-analysis due to heterogeneity in populations, interventions, and outcomes of the included studies. We used a framework analysis approach to summarize the evidence of de-implementation interventions aiming to reduce low-value cancer care [29]. The framework analysis approach included five stages (i.e., familiarization, framework selection, indexing, charting, and mapping and interpretation.) First, team members read included studies and familiarized themselves with the literature. Second, we identified conceptual frameworks that served as the codes for data abstraction [27, 30, 31]. To describe studies in which researchers have studied de-implementation interventions aiming to reduce low-value cancer care, we used a thematic framework that included publication year, design, outcome(s), type of cancer, objective(s), country, setting, type/name of low-value care, de-implementation intervention description (e.g., type, name), single or multifaceted de-implementation intervention strategy, any framework/conceptual or theoretical model used, barriers to de-implementation intervention use, the effectiveness of the de-implementation intervention, and assessment of patients’ priorities/perceptions when de-implementing the low-value care. Next, pairs of authors completed indexing and charting by placing selected text from included articles into the appropriate cells within our framework. Data from the included studies were extracted into a standardized data extraction form in Microsoft Excel (version 2016). Last, we analyzed extracted data from each cell to describe the studies and findings of de-implementation interventions aiming to reduce low-value cancer care.

Results

Study selection

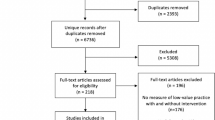

The searches in PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, and Scopus yielded 5290 citations. These citations were exported to Endnote (Version 20) and 2504 duplicates were removed using the Endnote deduplication feature. Additionally, eight records were identified through hand searching. This resulted in a total of 2794 unique citations found across all database searches. Titles and abstracts of the 2794 articles were screened; 52 were selected for full-text screening. Of the 52 studies, 40 were excluded at full-text screening or during extraction attempts with the consensus of two coauthors; 12 unique eligible studies were included [32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43] (Fig. 1).

Characteristics of included studies

The included studies were published between 2003 and 2020. Most included studies (n = 10) used either interrupted time series or pre–post-study designs [33,34,35, 37,38,39,40,41,42,43], one study was an observational cohort study [36], and one study was randomized clinical trials [32]. Most of the included studies (n = 8) were conducted in the USA [32, 33, 35, 36, 39, 40, 42, 43]. The remaining studies were conducted in England (n = 2) [37, 41], France (n = 1) [38], and Netherlands (n = 1) [34]. The studies covered several cancer types including prostate cancer (n = 5) [32, 35, 39, 40, 43], gastrointestinal cancer (n = 3) [32, 36, 38], lung cancer (n = 2) [36, 42], breast cancer (n = 2) [33, 36], and hematologic cancers (n = 1) [37]. Some of the included studies focused on more than one cancer type [32, 34, 36, 41]. Five studies focused on low-value screening services (e.g., inappropriate PSA-based prostate cancer screening among men aged 75 and over) [32, 35, 39, 40, 43], two studies focused on de-implementing low-value diagnostic tests (e.g., ordering of diagnostic markers) [33, 38], and five studies focused on de-implementing low-value treatment procedures (e.g., inappropriate use of peripheral intravenous and urinary catheters) [34, 36, 37, 41, 42]. Characteristics of included studies are shown in Table 2.

Quality assessment of studies

The overall quality of an included randomized clinical trial was good (assessed by NIH Quality Assessment Tool for the controlled intervention studies) [32]. The overall quality of an included observational cohort study was fair (assessed by NIH Quality Assessment Tool for the observational cohort and cross-sectional studies) [36]. The overall quality of four of the pre–post designs studies was poor [33, 39, 41, 43], the quality of four of them was fair [35, 37, 38, 42], and the quality of two of them was good (assessed by NIH Quality Assessment Tool for the before-after (pre–post) studies with no control group studies) [34, 40]. The details of the quality assessment of the included studies are shown in Additional file 3.

De-implementation interventions’ characteristics

All included studies described at least one de-implementation intervention. De-implementation interventions’ characteristics can be found in Table 3. From the four types of de-implementation action (i.e., removing, replacing, reducing, and restricting) [27], all of the actions in included studies aimed at reducing low-value care without offering a high-value care replacement. Most of the implemented interventions (n = 11) were multifaceted (i.e., interventions included two or more components) [33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43]. Developing a decision support tool (n = 11) (usually integrated within the electronic health record system to assist clinicians) [32,33,34,35,36,37,38, 40,41,42,43], auditing and providing feedback (n = 7) [33, 34, 37, 39, 41,42,43], educating clinicians through developing and disseminating new guidelines (n = 5) [33, 34, 41,42,43], and having a clinical champion (n = 3) [34, 39, 43] are the common components of many of the de-implementation interventions. Only one of the de-implementation interventions (i.e., one-page, written evidence-based decision support sheet to present benefits and harms information in reducing intentions for screening) focused on changing the patients’ behavior [32]. Other studies aimed at de-implementing low-value care by changing providers’ behavior.

De-implementation interventions’ determinants

While none of the included studies systematically assessed the determinants of de-implementing interventions, six of them mentioned some of the determinants such as clinicians’ lack of confidence and trust in the new evidence, bias inertia toward low-value care (i.e., status quo bias), and resource availability [33, 34, 36,37,38, 40, 41]. None of the included studies applied de-implementation theories, models, and frameworks to identify the determinants of the use of the de-implementation interventions. However, all the included studies developed their de-implementation interventions based on behavioral, communication, and economic theories or published guidelines (e.g., National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines for staging evaluations in men with early-stage prostate cancer).

De-implementation interventions’ effectiveness

The main objective of all included studies was to test the effectiveness of de-implementation interventions (e.g., examining the effectiveness of alternate formats for presenting benefits and harms information in reducing intentions for unnecessary prostate and colorectal cancer screening). Six of the de-implementation interventions were effective in reducing low-value care [35, 36, 38, 40, 42, 43], five studies reported mixed results (e.g., a multistep intervention including collaborative-wide data review and performance feedback significantly decreased the bone scan rate from 3.7 to 1.3% (P = 0.03), while it decreased computerized tomography from 5.2 to 3.2% in a non-significant way (P = 0.17)) [33, 34, 37, 39, 41], and in one study outcomes showed no difference across intervention arms [32]. The most effective component among interventions was integrating a decision support tool (e.g., a clinical computerized decision support tool that alerts clinicians of potentially inappropriate orders in real-time) within the electronic health record system [35, 36, 38, 40,41,42,43]. Gob et al. study showed among many interventions they have implemented to increase the proportion of one-unit red cell transfusion orders (vs. two units), modifying the transfusion orders templates was the only intervention that resulted in an immediate and sustained change to the system [41].

Discussion

This systematic review aimed to summarize existing de-implementation efforts in cancer care delivery, including what types of interventions were developed, their effectiveness, and factors that may affect the use of the de-implementation intervention. We found most of the studies were published in recent years (i.e., after 2015) and were conducted in the USA. We found that majority of de-implementation interventions were multi-faceted, and they were successful in reducing low-value care. Included studies covered over-utilization across the cancer care continuum (i.e., over-screening, over-diagnosis, and over-treatment) with a focus on over-screening (e.g., for prostate cancer). Most of the de-implementation interventions structured as multistep interventions followed the Plan-Do-Study-Act cycle. Generally, first, a multidisciplinary team led by a clinical champion audited the clinicians’ practice data, compared the data with evidence-based guidelines (e.g., National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines). Second, the baseline practice data and discrepancies with evidenced-based guidelines are presented to clinicians at each practice (i.e., feedback). This is an important step as a recent review finds providing feedback to clinicians is associated with reducing overuse of tests and treatments, and increasing guidelines adherence [44]. Additionally, providing clinicians with evidence-based interventions through educational programs can help them to substitute low-value care with high-value care. A systematic review on the effects of de-implementation interventions aimed at reducing low-value nursing procedures showed the majority of the studies with a positive significant effect used a de-implementation strategy with an educational component [45]. Many of included studies also mentioned developing a clinical decision support tool often integrated within the electronic health record system (e.g., a pop-up message to alert clinicians) to assist clinicians to reduce low-value care. Different studies showed guideline enforcement strategies (e.g., clinical decision support tools) are the most effective strategies to reduce low-value services [41, 46]. Our review also revealed a paucity of evidence in five key areas.

First, we found that very few interventions have been used to de-implement low-value cancer care practices. Lack of de-implementation interventions to reduce low-value care may explain why low-value cancer care persists, despite significant forces over the past decade to reduce low-value care [13, 14]. While educational campaigns and medical guidelines have shown some potential in raising awareness regarding low-value services in cancer care [47], recent studies demonstrate that, in many areas, those recommendations had a limited effect on reducing low-value care [48, 49]. For example, Encinosa et al. found while the odds of antiemetic overuse decreased significantly during the first 6 months after the dissemination of Choosing Wisely recommendations, the decrease however was temporary, and it increased again after 6 months [49]. De-implementation is a planned process that involves interaction between multilevel and multifaceted factors [50]. Therefore, simply diffusing evidence without active efforts to abandon a particular low-value practice is unlikely to lead to meaningful results. This finding highlights the need for moving from passive de-implementation (i.e., solely relying on disseminating evidence and expecting that clinicians will voluntarily follow new guidelines) to active de-implementation (i.e., implementing interventions purposefully aimed at reducing low-value care, such as workflow modification and systems facilitating change).

Second, the focus of all the included studies was to test the effectiveness of de-implementation interventions. Future studies should focus on other aspects of de-implementation interventions such as the relationship between de-implementation interventions and health disparities, and the unintended consequences of the de-implementing of an intervention [27]. Studying the relationship between de-implementation interventions and health disparities is needed to ensure that de-implementation efforts do not exacerbate existing inequities. Not all populations react to de-implementation efforts in the same way [51, 52]. For example, while prior research showed Black and Hispanic Americans are at higher risk of both overuse of low-value care and underuse of high-value care [53], they have been found to perceive de-implementation efforts as withholding potentially beneficial care [54]. Additionally, none of the included studies assessed the unintended consequences of the de-implementation interventions. This is an important gap because de-implementation interventions may have unintended consequences that affect patients, such as increased distrust of the health care system, questioning of underlying motives of de-implementation (e.g., patients may perceive de-implementation interventions as cost-cutting efforts), and undermining patient autonomy [55,56,57]. It is therefore imperative that the future evaluations of de-implementation interventions consider broader measures to assess the de-implementation interventions’ effects, both positive and negative.

Third, medical centers in included studies developed their de-implementation interventions based on behavioral, communication, and economic theories or published guidelines. However, none of the included studies used de-implementation theories, models, or frameworks to inform their conceptualization or to identify the determinants of using de-implementation interventions. Determinants of implementation and de-implementation may have many similarities (e.g., they both need leadership engagement); however, some elements may be unique to de-implementation [58]. For example, Helfrich et al. highlighted that de-implementation may require a process of unlearning to change knowledge, intentions, and beliefs about a low-value service [46]. Recent reviews identified some theories, models, or frameworks specifically developed for the de-implementation of low-value care [59, 60]. Using theoretical frameworks specifically developed for de-implementation of low-value care therefore may help researchers to better evaluate the de-implementation process, identify determinants of de-implementing low-valued care, and explore interactions among de-implementation determinants (e.g., peer pressure may moderate the influence of guidelines) [35].

Fourth, we found only a few of included studies mentioned the determinants of de-implementation of low-value care practices. This is an important gap, because similar to implementing a novel intervention or policy, de-implementation of a low-value practice is a complex process that is influenced by multi-level factors (i.e., individual-level and organizational level factors) [27, 61, 62]. Many individual-level factors (patient- and clinician-level) may contribute to the success of de-implementation interventions [63]. For example, patients’ perspectives and preferences [45], and trust in their clinicians [64] are key determinants of many practices in cancer care, and ignoring those factors in efforts to de-implement low-value care may jeopardize the de-implementation process. Prior research also showed that most patients overestimate the benefits and underestimate the harms of medical services [55, 56, 65]. Additionally, recent studies showed clinician-level factors such as knowledge, interpersonal skills, motivation, professional confidence, and beliefs about the consequences of practicing a low value explain why clinicians stop providing certain low-value care while not others [66, 67]. In addition to individual-level factors, many collective-level factors (e.g., organizational culture, leadership, resources, and financial status) also contribute to the utilization of low-value care [45]. In many cases, healthcare organizations intentionally decide to continue providing low-value care. For example, some hospitals, particularly those with financial difficulties, may resist de-implementing low-value practices (e.g., novel experimental technologies) if those services generate significant revenue or provide another relative advantage (e.g., competitive edge) over other hospitals [27, 48, 61]. Future research should consider the association between de-implementation interventions and both individual-level (e.g., perceptions of appropriate use and overuse of health services in oncology) and collective-level factors (e.g., community, organizational characteristics, and reimbursement policies). As previously mentioned, theories, models, and frameworks of determinants of de-implementation may aid in identifying these determinants.

Fifth, almost all the included studies focused on changing clinicians’ behaviors without considering patients’ role. This is an important gap as a systematic review on how low-value breast cancer surgery has been de-implemented in response to Choosing Wisely recommendations identified patient decision-making as a key determinant of de-implementation of low-value breast cancer surgery, suggesting that patients’ role should be included in other de-implementation studies [68]. Many studies showed involving patients in deciding a course of care (i.e., shared decision-making) is a powerful tool for reducing low-value care [22, 62, 69, 70]. However, none of the included studies used a shared decision-making process between the clinician and the patient regarding the use of a specific potentially low-value service. Besides, patients’ attitudes toward different parts of the cancer care continuum are different. For example, while patients are generally in favor of taking fewer medications, they also believe that more testing and screening lead to better outcomes [55]. Research is needed to explore the relationship between different categories of low-value cancer care (e.g., screening, testing, treatment) and de-implementation intervention effectiveness.

This review has some limitations. First, we limited our systematic reviews to English-only articles which could result in biased estimates of effect and reduce generalizability. Second, many practices such as inappropriate use of antibiotics to manage febrile neutropenia (e.g., administering empiric vancomycin) could be considered as low-value care [71]. However, we did not include studies on discontinuing such practices (e.g., antibiotic stewardship interventions) because they were not among Choosing Wisely recommendations. Finally, because of challenges in identifying low-value health care [72], it is possible that some organizations de-implemented interventions without labeling them as low-value care. Therefore, despite a comprehensive literature search, there remains a possibility that we may have missed relevant studies. Additionally, all the included studies were conducted in the USA or European countries; therefore, the findings may not be generalizable to other regions.

Conclusion

This review demonstrated a paucity of evidence in many key areas of the de-implementation of low-value care in cancer care delivery. First, the assumption that new evidence, guidelines, and reimbursement policies alone will change the way clinicians practice is likely misplaced. Relying on clinicians to change their practice in the absence of well-designed de-implementation interventions is unlikely to reduce low-value care. Second, future research should include a broader range of variables when studying de-implementation. Factors such as patients’ perspectives and preferences; patient satisfaction; and system-level factors such as organizational culture, leadership, and resources are understudied yet likely relevant de-implementation determinants. Finally, future studies should assess unintended effects of de-implementing low-value care, such as increased distrust of the health care system, and undermining patient autonomy.

Availability of data and materials

The data used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request and subject to IRB guidelines.

Abbreviations

- NIH:

-

National Institutes of Health

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses

- PSA:

-

Prostate-specific antigen

References

Mariotto AB, Enewold L, Zhao J, Zeruto CA, Yabroff KR. Medical care costs associated with cancer survivorship in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2020;29:1304–12 AACR.

Grimshaw JM, Patey AM, Kirkham KR, Hall A, Dowling SK, Rodondi N, et al. De-implementing wisely: developing the evidence base to reduce low-value care. BMJ Qual Saf. 2020;29:409–17 BMJ Publishing Group Ltd.

Prasad V, Ioannidis JP. Evidence-based de-implementation for contradicted, unproven, and aspiring healthcare practices. Implement Sci. 2014;9:1.

Maratt JK, Kerr EA, Klamerus ML, Lohman SE, Froehlich W, Bhatia RS, et al. Measures used to assess the impact of interventions to reduce low-value care: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(9):1857–64.

Baker A. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Vol. 323. No. 7322. British Medical Journal Publishing Group; 2001.

Andriole GL, Crawford ED, Grubb RL III, Buys SS, Chia D, Church TR, et al. Mortality results from a randomized prostate-cancer screening trial. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1310–9 Mass Medical Soc.

Schröder FH, Hugosson J, Roobol MJ, Tammela TL, Ciatto S, Nelen V, et al. Screening and prostate-cancer mortality in a randomized European study. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1320–8 Mass Medical Soc.

Saini V, Lin KW. Introducing Lown Right Care: reducing overuse and underuse. Am Fam Physician. 2018;98:560.

Boughey JC, Haffty BG, Habermann EB, Hoskin TL, Goetz MP. Has the time come to stop surgical staging of the axilla for all women age 70 years or older with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer? Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24:614–7 Springer.

Mitera G, Earle C, Latosinsky S, Booth C, Bezjak A, Desbiens C, et al. Choosing Wisely Canada cancer list: ten low-value or harmful practices that should be avoided in cancer care. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11:e296–303 American Society of Clinical Oncology Alexandria, VA.

Oncology AS of C. Ten things physicians and patients should question: Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation, American Society of Clinical Oncology, retrieved; 2014. p. 25.

Levinson W, Kallewaard M, Bhatia RS, Wolfson D, Shortt S, Kerr EA. ‘Choosing Wisely’: a growing international campaign. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;24:167–74 BMJ Publishing Group Ltd.

Cassel CK, Guest JA. Choosing wisely: helping physicians and patients make smart decisions about their care. JAMA. 2012;307:1801–2 American Medical Association.

Baskin AS, Wang T, Berlin NL, Skolarus TA, Dossett LA. Scope and characteristics of choosing wisely in cancer care recommendations by professional societies. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6:1463–5 American Medical Association.

Baxi SS, Kale M, Keyhani S, Roman BR, Yang A, Derosa A, et al. Overuse of health care services in the management of cancer: a systematic review. Med Care. 2017;55:723 NIH Public Access.

Rocque G, Blayney DW, Jahanzeb M, Knape A, Markham MJ, Pham T, et al. Choosing wisely in oncology: are we ready for value-based care? Journal of oncology practice. Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2017;13:e935–43.

Schleicher SM, Bach PB, Matsoukas K, Korenstein D. Medication overuse in oncology: current trends and future implications for patients and society. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:e200–8 Elsevier.

Khatcheressian JL, Hurley P, Bantug E, Esserman LJ, Grunfeld E, Halberg F, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology Breast cancer follow-up and management after primary treatment: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:961–5.

Cardoso F, Harbeck N, Fallowfield L, Kyriakides S, Senkus E, Group EGW. Locally recurrent or metastatic breast cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:vii11–9 Oxford University Press.

Enright K, Desai T, Sutradhar R, Gonzalez A, Powis M, Taback N, et al. Factors associated with imaging in patients with early breast cancer after initial treatment. Curr Oncol. 2018;25:126 Multimed Inc.

Simos D, Catley C, van Walraven C, Arnaout A, Booth CM, McInnes M, et al. Imaging for distant metastases in women with early-stage breast cancer: a population-based cohort study. CMAJ. 2015;187:E387–97.

Colla CH, Mainor AJ, Hargreaves C, Sequist T, Morden N. Interventions aimed at reducing use of low-value health services: a systematic review. Med Care Res Rev. 2017;74:507–50 SAGE Publications Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA.

Niven DJ, Mrklas KJ, Holodinsky JK, Straus SE, Hemmelgarn BR, Jeffs LP, et al. Towards understanding the de-adoption of low-value clinical practices: a scoping review. BMC Med. 2015;13:1–21 BioMed Central.

Hailemariam M, Bustos T, Montgomery B, Barajas R, Evans LB, Drahota A. Evidence-based intervention sustainability strategies: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2019;14:1–12 BioMed Central.

Nilsen P, Bernhardsson S. Context matters in implementation science: a scoping review of determinant frameworks that describe contextual determinants for implementation outcomes. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19:1–21 BioMed Central.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int J Surg. 2021;88:105906 Elsevier.

Norton WE, Chambers DA. Unpacking the complexities of de-implementing inappropriate health interventions. Implement Sci. 2020;15:1–7 Springer.

Study Quality Assessment Tools | NHLBI, NIH. Available from: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools. Cited 2021 Apr 12.

Ritchie J, Lewis J, Nicholls CM, Ormston R. Qualitative research practice: a guide for social science students and researchers. SAGE; 2013.

McKay VR, Morshed AB, Brownson RC, Proctor EK, Prusaczyk B. Letting go: conceptualizing intervention de-implementation in public health and social service settings. Am J Community Psychol. 2018;62:189–202 Wiley Online Library.

Morgan DJ, Leppin A, Smith CD, Korenstein D. A practical framework for understanding and reducing medical overuse: conceptualizing overuse through the patient-clinician interaction. J Hosp Med. 2017;12:346 NIH Public Access.

Sheridan SL, Sutkowi-Hemstreet A, Barclay C, Brewer NT, Dolor RJ, Gizlice Z, et al. A comparative effectiveness trial of alternate formats for presenting benefits and harms information for low-value screening services: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:31–41 American Medical Association.

Hill LA, Vang CA, Kennedy CR, Linebarger JH, Dietrich LL, Parsons BM, et al. A strategy for changing adherence to national guidelines for decreasing laboratory testing for early breast cancer patients. WMJ. 2018;117(2):68–72.

Laan BJ, Maaskant JM, Spijkerman IJ, Borgert MJ, Godfried MH, Pasmooij BC, et al. De-implementation strategy to reduce inappropriate use of intravenous and urinary catheters (RICAT): a multicentre, prospective, interrupted time-series and before and after study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:864–72 Elsevier.

Ciprut S, Sedlander E, Watts KL, Matulewicz RS, Stange KC, Sherman SE, et al. Designing a theory-based intervention to improve the guideline-concordant use of imaging to stage incident prostate cancer. Urol Oncol. 2018;36(5):246–51 Elsevier.

Hoque S, Chen BJ, Schoen MW, Carson KR, Keller J, Witherspoon BJ, et al. End of an era of administering erythropoiesis stimulating agents among Veterans Administration cancer patients with chemotherapy-induced anemia. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0234541 Public Library of Science San Francisco, CA USA.

Butler CE, Noel S, Hibbs SP, Miles D, Staves J, Mohaghegh P, et al. Implementation of a clinical decision support system improves compliance with restrictive transfusion policies in hematology patients. Transfusion. 2015;55:1964–71 Wiley Online Library.

Durieux P, Ravaud P, Porcher R, Fulla Y, Manet C-S, Chaussade S. Long-term impact of a restrictive laboratory test ordering form on tumor marker prescriptions. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2003;19:106–13 Cambridge University Press.

Ross I, Womble P, Ye J, Linsell S, Montie JE, Miller DC, et al. MUSIC: patterns of care in the radiographic staging of men with newly diagnosed low risk prostate cancer. J Urol. 2015;193:1159–62 Wolters Kluwer Philadelphia, PA.

Shelton JB, Ochotorena L, Bennett C, Shekelle P, Kwan L, Skolarus T, et al. Reducing PSA-based prostate cancer screening in men aged 75 years and older with the use of highly specific computerized clinical decision support. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30:1133–9 Springer.

Gob A, Bhalla A, Aseltine L, Chin-Yee I. Reducing two-unit red cell transfusions on the oncology ward: a choosing wisely initiative. BMJ Open Qual. 2019;8:e000521 British Medical Journal Publishing Group.

Martin Goodman L, Moeller MB, Azzouqa A-G, Guthrie AE, Dalby CK, Earl MA, et al. Reduction of inappropriate prophylactic pegylated granulocyte colony-stimulating factor use for patients with non–small-cell lung cancer who receive chemotherapy: an ASCO quality training program project of the Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Institute. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12:e101–7 American Society of Clinical Oncology Alexandria, VA.

Miller DC, Murtagh DS, Suh RS, Knapp PM, Schuster TG, Dunn RL, et al. Regional collaboration to improve radiographic staging practices among men with early stage prostate cancer. J Urol. 2011;186:844–9 Wolters Kluwer Philadelphia, PA.

Harrison R, Hinchcliff RA, Manias E, Mears S, Heslop D, Walton V, et al. Can feedback approaches reduce unwarranted clinical variation? A systematic rapid evidence synthesis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20:1–18 BioMed Central.

Augustsson H, Ingvarsson S, Nilsen P, von Thiele Schwarz U, Muli I, Dervish J, et al. Determinants for the use and de-implementation of low-value care in health care: a scoping review. Implement Sci Commun. 2021;2:1–17 Springer.

Helfrich CD, Rose AJ, Hartmann CW, van Bodegom-Vos L, Graham ID, Wood SJ, et al. How the dual process model of human cognition can inform efforts to de-implement ineffective and harmful clinical practices: a preliminary model of unlearning and substitution. J Eval Clin Pract. 2018;24:198–205 Wiley Online Library.

Howard DH, Tangka FK, Guy GP, Ekwueme DU, Lipscomb J. Prostate cancer screening in men ages 75 and older fell by 8 percentage points after Task Force recommendation. Health Aff. 2013;32:596–602.

Saletti P, Sanna P, Gabutti L, Ghielmini M. Choosing wisely in oncology: necessity and obstacles. Esmo Open. 2018;3:e000382 BMJ Publishing Group Limited.

Encinosa W, Davidoff AJ. Changes in antiemetic overuse in response to choosing wisely recommendations. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:320–6 American Medical Association.

Norton WE, McCaskill-Stevens W, Chambers DA, Stella PJ, Brawley OW, Kramer BS. Deimplementing ineffective and low-value clinical practices: research and practice opportunities in community oncology settings. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2021;5:pkab020 Oxford University Press.

Shelton RC, Brotzman LE, Johnson D, Erwin D. Trust and mistrust in shaping adaptation and de-implementation in the context of changing screening guidelines. Ethn Dis. 2021;31:119–32.

Helfrich CD, Hartmann CW, Parikh TJ, Au DH. Promoting health equity through de-implementation research. Ethn Dis. 2019;29:93 Ethnicity & Disease Inc.

Schpero WL, Morden NE, Sequist TD, Rosenthal MB, Gottlieb DJ, Colla CH. For selected services, blacks and Hispanics more likely to receive low-value care than whites. Health Aff. 2017;36:1065–9.

Webb Hooper M, Mitchell C, Marshall VJ, Cheatham C, Austin K, Sanders K, et al. Understanding multilevel factors related to urban community trust in healthcare and research. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:3280 Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute.

Schleifer D, Rothman DJ. “The ultimate decision is yours”: exploring patients’ attitudes about the overuse of medical interventions. PLoS One. 2012;7:e52552 Public Library of Science.

Carman KL, Maurer M, Yegian JM, Dardess P, McGee J, Evers M, et al. Evidence that consumers are skeptical about evidence-based health care. Health Aff. 2010;29:1400–6.

Hoffmann TC, Del Mar C. Patients’ expectations of the benefits and harms of treatments, screening, and tests: a systematic review. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:274–86.

Prusaczyk B, Swindle T, Curran G. Defining and conceptualizing outcomes for de-implementation: key distinctions from implementation outcomes. Implement Sci Commun. 2020;1:43.

Nilsen P, Ingvarsson S, Hasson H, von Thiele Schwarz U, Augustsson H. Theories, models, and frameworks for de-implementation of low-value care: a scoping review of the literature. Implement Res Pract. 2020;1:2633489520953762 SAGE Publications Sage UK: London, England.

Walsh-Bailey C, Tsai E, Tabak RG, Morshed AB, Norton WE, McKay VR, et al. A scoping review of de-implementation frameworks and models. Implement Sci. 2021;16:100.

Norton WE, Chambers DA, Kramer BS. Conceptualizing de-implementation in cancer care delivery. J Clin Oncol. 2018;37:93–6.

Tabriz AA, Neslund-Dudas C, Turner K, Rivera MP, Reuland DS, Lafata JE. How health-care organizations implement shared decision-making when it is required for reimbursement: the case of lung cancer screening. Chest. 2021;159:413–25 Elsevier.

Bierbaum M, Rapport F, Arnolda G, Nic Giolla Easpaig B, Lamprell K, Hutchinson K, et al. Clinicians’ attitudes and perceived barriers and facilitators to cancer treatment clinical practice guideline adherence: a systematic review of qualitative and quantitative literature. Implement Sci. 2020;15:1–24 Springer.

Wang T, Baskin A, Miller J, Metz A, Matusko N, Hughes T, et al. Trends in breast cancer treatment de-implementation in older patients with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer: a mixed methods study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2021;28:902–13 Springer.

Gogineni K, Shuman KL, Chinn D, Gabler NB, Emanuel EJ. Patient demands and requests for cancer tests and treatments. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:33–9 American Medical Association.

Smith ME, Vitous CA, Hughes TM, Shubeck SP, Jagsi R, Dossett LA. Barriers and facilitators to de-implementation of the Choosing Wisely® guidelines for low-value breast cancer surgery. Ann Surg Oncol. 2020:1–11. Springer.

Skolarus TA, Forman J, Sparks JB, Metreger T, Hawley ST, Caram MV, et al. Learning from the “tail end” of de-implementation: the case of chemical castration for localized prostate cancer. Implement Sci Commun. 2021;2:1–16 BioMed Central.

Wang T, Baskin AS, Dossett LA. Deimplementation of the Choosing Wisely recommendations for low-value breast cancer surgery: a systematic review. JAMA Surg. 2020;155:759–70 American Medical Association.

Thompson R, Muscat DM, Jansen J, Cox D, Zadro JR, Traeger AC, et al. Promise and perils of patient decision aids for reducing low-value care. BMJ Qual Saf. 2021;30:407–11 BMJ Publishing Group Ltd.

Veroff D, Marr A, Wennberg DE. Enhanced support for shared decision making reduced costs of care for patients with preference-sensitive conditions. Health Aff. 2013;32:285–93.

Pillinger KE, Bouchard J, Withers ST, Mediwala K, McGee EU, Gibson GM, et al. Inpatient antibiotic stewardship interventions in the adult oncology and hematopoietic stem cell transplant population: a review of the literature. Ann Pharmacother. 2020;54:594–610 SAGE Publications Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA.

Garner S, Docherty M, Somner J, Sharma T, Choudhury M, Clarke M, et al. Reducing ineffective practice: challenges in identifying low-value health care using Cochrane systematic reviews. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2013;18:6–12 SAGE Publications Sage UK: London, England.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors made significant contributions to the manuscript. AAT and SB conceived and designed the study. AAT and RC developed and tested the search strategy. RC deployed the search strategy. KT, AC, YH, GW, and ON reviewed all identified publications, identified those that met the inclusion criteria, as well as extracted and analyzed content from the relevant publications. RC and AAT supervised the conduct of the study and data collection. AAT, SB, KT, AC, and YH completed the search and reviewed the final manuscript file. AAT, KT, AC, YH, GW, and ON performed risk of bias and reviewed the final manuscript. AAT drafted the manuscript, and all authors contributed substantially to its revision. KT, AC, YH, and SB provided critical revisions to the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. AAT takes responsibility for the paper as a whole.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable. Registered in PROSPERO (registration number: CRD42021252482).

Consent for publication

Our manuscript does not contain any identifiable data in any form, either at the organizational level or individual level.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

PRISMA 2020 Checklist.

Additional file 2.

De-implementing Low-Value Care in Cancer Care Delivery Search Strategy.

Additional file 3.

Quality Assessment Tools Used for Assessing the Quality of included Studies.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Alishahi Tabriz, A., Turner, K., Clary, A. et al. De-implementing low-value care in cancer care delivery: a systematic review. Implementation Sci 17, 24 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-022-01197-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-022-01197-5