Abstract

Background

In the UK there are almost three times as many beds in care homes as in National Health Service (NHS) hospitals. Care homes rely on primary health care for access to medical care and specialist services. Repeated policy documents and government reviews register concern about how health care works with independent providers, and the need to increase the equity, continuity and quality of medical care for care homes. Despite multiple initiatives, it is not known if some approaches to service delivery are more effective in promoting integrated working between the NHS and care homes. This study aims to evaluate the different integrated approaches to health care services supporting older people in care homes, and identify barriers and facilitators to integrated working.

Methods

A systematic review was conducted using Medline (PubMed), CINAHL, BNI, EMBASE, PsycInfo, DH Data, Kings Fund, Web of Science (WoS incl. SCI, SSCI, HCI) and the Cochrane Library incl. DARE. Studies were included if they evaluated the effectiveness of integrated working between primary health care professionals and care homes, or identified barriers and facilitators to integrated working. Studies were quality assessed; data was extracted on health, service use, cost and process related outcomes. A modified narrative synthesis approach was used to compare and contrast integration using the principles of framework analysis.

Results

Seventeen studies were included; 10 quantitative studies, two process evaluations, one mixed methods study and four qualitative. The majority were carried out in nursing homes. They were characterised by heterogeneity of topic, interventions, methodology and outcomes. Most quantitative studies reported limited effects of the intervention; there was insufficient information to evaluate cost. Facilitators to integrated working included care home managers' support and protected time for staff training. Studies with the potential for integrated working were longer in duration.

Conclusions

Despite evidence about what inhibits and facilitates integrated working there was limited evidence about what the outcomes of different approaches to integrated care between health service and care homes might be. The majority of studies only achieved integrated working at the patient level of care and the focus on health service defined problems and outcome measures did not incorporate the priorities of residents or acknowledge the skills of care home staff. There is a need for more research to understand how integrated working is achieved and to test the effect of different approaches on cost, staff satisfaction and resident outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In the UK care homes are the major provider of long term and intermediate care for older people [1–3]. There are 18, 255 care homes providing 459, 448 beds, almost three times as many as the 167, 000 hospital beds available [4]. Although people living in care homes have complex needs and represent the oldest and most frail of the older population in the UK, research consistently demonstrates that they have erratic access to NHS services, particularly those that offer specialist expertise in areas such as dementia and end of life care [5–9].

Inappropriate and unplanned hospital admissions, recognition of unmet health needs, concerns about supporting patient dignity, end of life care and access to health services have triggered multiple care home specific policy initiatives and interventions [10, 11]. A consultation event that involved care home and health care representatives identified multiple examples of the NHS working with care homes to improve information exchange, palliative care, reduce falls, and unplanned admissions to hospital [12]. These interventions often involve the introduction of specialist health workers and teams or problem specific workers to achieve the desired outcomes [13, 14].

Primary health care services in England spend significant amounts of time providing care for older people resident in these settings [15, 16, 7, 8] (Goodman, C et al: Can clinical benchmarking improve bowel care in care homes for older people? Final report submitted to the DoH Nursing Quality Research Initiative PRP, Centre for Research in Primary and Community Care, University of Hertfordshire, 2007). However, relatively little is known about how health care services work with the (largely unqualified) workforce to provide care to a population that has complex physical and medication needs, experiences high level of cognitive impairment, depression and is in the last few years of life [17, 18]. The involvement of health care services in care home settings is often defined by what care home staff are not allowed to do rather than a clear understanding of how the two sectors complement each other, or work together [19]. In addition, it cannot be assumed that health service definitions of problems and services reflect how older people and care home staff define health needs and the types of health care they would like (Evans, C: The analysis of experiences and representations of older people's health in care homes to develop primary care nursing practice, unpublished PhD King's College London, 2008).

Initiatives that support continuity and integration of care for older people with complex needs across health and social care with public and private providers are increasingly recognised as important for continuity and quality of care [20, 21]. Integration of service provision can be defined as 'a single system of needs assessment, commissioning and/or service provision that aims to promote alignment and collaboration between the cure and care sectors [22]. There are different levels of integration between health care services [23]. In the context of integrated working with care homes, these can be summarised as:

Patient/Micro level

Close collaboration between different health care professionals and care home staff e.g for the benefit of individual patients.

Organisational/Meso level

Organisational or clinical structures and processes designed to enable teams and/or organisations to work collaboratively towards common goals (e.g. integrated health and social care teams).

Strategic/Macro level

Integration of structures and processes that link organisations and support shared strategic planning and development for example, when health care services jointly fund initiatives in care homes [24, 25].

To understand the evidence for the benefits of different approaches to health care services supporting older people in care homes, we conducted a systematic review to identify studies using integrated working between primary health care professionals and care homes for older people; evaluated their impact on the health and well being of older people in care homes, and identified barriers and facilitators to integrated working.

Methods

The review was conducted according to inclusion criteria and methods pre-specified in a protocol developed by the authors before the review began.

Inclusion criteria

We included interventions designed to develop, promote or facilitate integrated working between care home or nursing home staff and health care practitioners. Interventions that involved staff going in to provide education or training to care home/nursing home staff were included as long as there was some description of joint working or collaboration. We excluded studies where staff were employed specifically for the purpose of the research without consideration of how the findings might be integrated into ongoing practice (i.e. project staff introduced for a limited time to deliver a specific intervention). For a study to be included there had to be evidence of at least one of the following:

Clear evidence of joint working

Joint goals or care planning

Joint arrangements covering operational and strategic issues

Shared or single management arrangements

Joint commissioning at macro and micro levels

Studies also had to report at least one of the following outcomes:

Health and well being of older people (e.g. changes in health status, quality of life)

Service use (e.g. number of GP visits, hospital admissions)

Cost such as savings due to avoided hospitalisations

Process related outcomes (such as changes in quality of care, increased staff knowledge, uptake of training and education and professional satisfaction)

As the literature in this area is limited we included all studies that involved an element of evaluation. This included controlled and uncontrolled studies. However, because they are more susceptible to bias, studies without a control were used to describe and catalogue interventions rather than evaluate effectiveness. Process evaluations and qualitative studies including those using action research methodologies were included in order to identify facilitators and barriers to integrated working.

Identification of studies

The electronic search strategy was conducted in February 2009. We searched the following electronic databases: Medline (PubMed), CINAHL, BNI, EMBASE, PsycInfo, DH Data, Kings Fund, Web of Science (WoS incl. SCI, SSCI, HCI) and the Cochrane Library incl. DARE. In addition, we contacted care home related interest groups and used lateral search techniques, such as checking reference lists of relevant papers, and using the 'Cited by' option on WoS, Google Scholar and Scopus, and the 'Related articles' option on PubMed and WoS. We applied no restrictions by date or country but included English language papers only. Details of the search terms used can be seen in Table 1.

Data extraction and synthesis

Electronic search results were downloaded into EndNote bibliographic software. Two reviewers independently (SD, FB) screened all titles and abstracts of citations identified by the electronic search, applied the selection criteria to potentially relevant papers, and extracted data from included studies using a standardised form. Any disagreements concerning studies to be included were resolved by consensus or by discussion with a third reviewer (CG).

Due to substantial heterogeneity in study design, interventions, participants and outcomes we did not pool studies in a meta-analysis. Instead a narrative summary of findings is presented and where possible we have reported dichotomous outcomes as relative risks (RR) and continuous data as mean differences (MD) (with 95% confidence intervals). Data in the evidence tables is presented with an indication of whether the intervention had a positive effect (+), a negative effect (-), or no statistically significant effect (0). The qualitative studies were used to generate a list of potential barriers and facilitators to integrated working. Each paper was systematically read by two researchers (SD, CV) to highlight any factors that may have impacted on the process, both those that were explicitly referred to by the authors and those identified by the reviewers within the papers' narratives.

The quality of the included studies was assessed using design assessment checklists informed by the Cochrane Collaboration risk of bias tool [26] and Spencer et al's quality assessment checklist for qualitative studies [27]. The core quality-assessment domains are summarised in Table 2. As other non controlled studies were used to inform contextual understanding rather than evaluate effectiveness they were not formally quality assessed.

Data were extracted from each study on methodology, type of intervention, outcomes, participants, and location. In addition, an interpretive approach based on Kodner and Spreeuwenberg's (2002) work on integrated working, was used to compare and contrast the nature and level of integration across the studies using the principles of framework analysis [28]. Each study was categorised in terms of the degree of integration and the complexity classified as micro, meso and or macro. In addition, based on the assumption that care homes with a higher level of integration would show evidence of correspondingly greater levels of support and contact with health care professionals, each study was analysed to identify the amount of contact, support and training given by the health professionals involved in the study.

Results

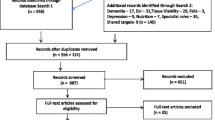

Figure 1 shows the flow of studies through the selection process. Seventeen studies (reported in 18 papers) met our inclusion criteria.

Description of studies

Ten studies were quantitative, (four of which were RCTs), one used mixed methods, two were process evaluations, three were qualitative and one was action research (see Table 3).

Nine were conducted in the UK, five in Australia, two in the USA and one in Sweden. Eleven (65%) studies were conducted in nursing homes, five in residential homes and one in a combination of both. Study participants included residents, relatives, care home staff both residential and nursing, and health professionals including general practitioners, district nurses, nurse specialists, pharmacists, psychiatrists and psychologists.

Seven studies were focused on individual care, for example, specific health care needs such as end of life [29–33] or wound care [34] and dementia [35]. Six studies focused on residents' needs as a group, such as detection and treatment of depression [36], bowel related problems (Goodman, C. et al: Can clinical benchmarking improve bowel care in care homes for older people? Final report submitted to the DoH Nursing Quality Research Initiative PRP, Centre for Research in Primary and Community Care, University of Hertfordshire, 2007.) and or supporting the care home staff interactions with residents through training [37] and improved prescribing [38–40]. A further four papers were service evaluations such as an in-reach team for care homes [41], a care home support team [42], and nurse practitioners [43, 44]. End of life care accounted for five papers [29–33], three of which focused on care pathways [30–32].

Risk of bias

There were seven controlled studies of which four were RCTs. Although the RCTs could be expected to be less susceptible to bias than the non randomised studies the potential for bias in both groups of studies appeared to be high (see Tables 4 and 5).

A number of the studies appeared underpowered and for many follow up was short. The qualitative studies employed a range of methodologies including action research, interviews, focus groups and questionnaires. As with the quantitative studies, the quality was low, only two out of four [30, 33] had a clearly defined purpose and design. With one exception [33] descriptions of the study sample, data collection and analysis were inadequate and evidence of their credibility and transferability was limited (see Table 6).

Effectiveness

The heterogeneity of outcomes and, in particular, the interventions meant that making comparisons between studies was problematic. Three studies looked at the effect on prescribing [38–40], three included mortality as an outcome [39, 40, 44] and two looked at disruptive behaviour [35, 39]. The remaining outcomes, only included in single studies, were depression [36], hospital admissions [40], functional status [40], wound healing [34], and bowel related problems (Goodman, C et al: Can clinical benchmarking improve bowel care in care homes for older people? Final report submitted to the DoH Nursing Quality Research Initiative PRP, Centre for Research in Primary and Community Care, University of Hertfordshire, 2007). Full details of the results can be seen in Table 7. Although there were some improvements in outcomes, the majority of studies showed that the intervention had either mixed effects (that is improvement in one outcome but no effect or negative effect in another outcome), or no effect when compared with the control group. Insufficient information was available to evaluate the cost of integrated working between care homes and primary health care professionals.

The nature of integrated working

There was a great deal of variation in how health care services and care homes worked together and the frequency of contact. For example, whilst some studies involved weekly multidisciplinary team meetings [43], monthly meetings were more common (Goodman, C et al: Can clinical benchmarking improve bowel care in care homes for older people? Final report submitted to the DoH Nursing Quality Research Initiative PRP, Centre for Research in Primary and Community Care, University of Hertfordshire, 2007)[30]. All the studies potentially increased care home staff access to health care professional's support and advice, with 15 out of 17 involving care home staff in multidisciplinary interventions or joint working. Care home staff were involved in multidisciplinary meetings and in some studies their opinions were sought [40], but they were led by health care professionals, with health care orientated and defined goals. Staff training was an integral part of all studies bar three; only a few studies consulted with care home staff on their perceived training needs [29, 33]. The range of training input varied from as little as three hours [31] to seven seminars [37] or continuous training and support [43, 44].

The level of integration for all studies and the degree of support and training provided by NHS staff for care home is reported in Table 8. The majority of studies showed micro integration at the clinical level involving close collaboration between care home staff and health care professionals to achieve specific outcomes (12 out of the 17) e.g. wound care techniques and wound healing. The remaining five studies were integrated at the clinical level but also showed greater complexity of integration in terms of funding and organisation or strategy, one at the meso level [42] and four at the macro level [31, 41, 43, 44]. In service delivery, four studies used dedicated multidisciplinary teams to support staff and residents in care homes [42], three of which achieved their remit of avoiding unnecessary hospitalisation [41, 43, 44]. Two UK studies also had health service funded beds within care homes, one for use by a specialist health care nursing team [41] the other to provide end of life care [31]. A distinguishing feature of four out of the five studies classified at higher levels of integration was that care home staff received support and or training which was ongoing, as opposed to being offered at discrete time periods during the intervention. For example, nursing home staff were facilitated to recognise and manage acute conditions [43], to improve residents' overall care [44].

A number of cross cutting themes that influenced the achievement of integrated working were identified (See Tables 9 and 10). These included, care home access to services and the different working cultures of care home staff and health care professionals that acted as barriers and facilitators. Care home staff identified a lack of support from health care professionals and a failure to recognise their knowledge and skills [29, 33, 42]. There were negative perceptions on both sides with care home staff feeling that health care professionals were sometimes acting in a 'policing' rather than an advisory capacity [29, 42] and health care professionals perceiving care home staff as lacking in knowledge and expertise, and unwilling to change their practice [30].

Whilst input and training from health care staff was valued, for care home staff to access it, dedicated time and finance from care home managers was necessary. Holding sessions within the care home and setting up a learning contract with the staff could facilitate training [32]. Examples of positive interactions included one care home support team described as acting as a link to 'the outside world' by the care home, and supporting clinical decision making across the multi disciplinary team [42]. Difficulty in maintaining levels of staff skills and knowledge were exacerbated by the high staff turnover experienced by care homes [29, 32, 33]. However, one study found a higher rate of staff turnover amongst the health care professionals involved in the intervention than the senior staff in the care homes (Goodman, C et al: Can clinical benchmarking improve bowel care in care homes for older people? Final report submitted to the DoH Nursing Quality Research Initiative PRP, Centre for Research in Primary and Community Care, University of Hertfordshire, 2007). Consistency of care home managers was identified as an important factor in building collaborative working with health care professionals [32].

Discussion

We found 17 studies, eight of which were controlled evaluations. Although some of the studies reported positive outcomes most interventions had mixed or no effects when compared with the control group. There was insufficient information available to evaluate the cost of integrated working between care homes and primary health care professionals. Some of the qualitative studies suggested that integrated working had the potential to improve the quality of life for older people in care homes through increased support for care home staff and increased access to health care services. A small number of studies which were integrated at the macro or meso level, involved care homes that were supported by dedicated health service teams and health service funded beds or managed care, showed more positive outcomes such as avoidance of hospitalisation. They also differed from the micro integrated studies in their capacity to give ongoing support and training for care home staff, which had the potential to address one of the main identified barriers to integrated working and ultimately improve resident's care. This indicates that for integrated working to be successful, formal structures may need to be in place for health service delivery and organisation of care for care homes.

Despite the lack of evidence on effectiveness, studies consistently demonstrated key issues that supported or militated against integrated working. These findings are significant for future research and the development of interventions that rely on integrated working between health care services and care home staff. Barriers to integrated working included a failure to acknowledge the expertise of care home staff, their lack of access to health care services, as well as high care home staff turnover and limited availability of training. Facilitators to integrated working were the care home manager's support for the intervention, protected time and the inclusion of all levels of care home staff for training and support by health care professionals.

A common feature of the interventions was the use of multidisciplinary teams to improve one or more aspect of older people's health care. However, all the studies were led and conducted by health care professionals. There was no evidence of care home staff being involved in the definition or focus of the studies and some evidence that care home staff felt that their knowledge and views were not valued. Seven studies employed external project staff in some capacity, which implies that integrated working may require some external facilitation.

Three studies used integrated care pathways as a means of improving the quality of end of life care for older people resident in care homes. Care pathways may increase integrated working for the individual older people who have them, but this will not necessarily extend to the care home residents as a whole. The use of a shared assessment and care framework and documentation itself can become a useful source of continuity in an environment where there is high staff turnover and shift working in both sectors (Goodman, C et al: Can clinical benchmarking improve bowel care in care homes for older people? Final report submitted to the DoH Nursing Quality Research Initiative PRP, Centre for Research in Primary and Community Care, University of Hertfordshire, 2007).

Limitations of existing evidence

Given the limited number of studies in the review, their heterogeneity, poor quality, small size, and low level of detail, the scope for discussion of integrated working between care homes and primary health care professionals is limited and firm conclusions cannot be reached. Only five studies were conducted in residential care homes which reinforced previous findings that the majority of research is carried out in nursing homes, even though this is not where most older people in long term care live [14]. The absence of older people's views and resident centred outcomes from the studies was notable.

Moreover the majority of studies were only integrated at the micro level that is, close collaboration between care home staff and professionals, so little information was available on the impact of integration at meso and macro levels. There was wide variation amongst the studies in terms of their level of care home staff support and training, and the involvement of older people. Care home staff training and support ranged between those studies where it was ongoing and those where it was provided only on one occasion. Where there was support and training of care home staff it was not clear if the ultimate aim was to train staff to a level of expertise so that health services could withdraw.

Implications for research

There is a need for more research that addresses how integrated working can best be achieved and that evaluates the effect of integrated working on the health and wellbeing of older people, service use and cost. Research with care homes should reflect the context and constraints of working across public and independent services, and involve care homes in the planning and design of interventions. Moreover as this population is known to have multiple co-morbidities that are often compounded by cognitive impairment there is a need for more studies to look at improving the quality of care for the care home population as a whole. Future evaluations should be large enough to detect a difference and outcomes need to be meaningful to care home staff and residents.

Strengths and limitations of the review

We used systematic and rigorous methods to synthesise the current evidence on integrated working between care homes and health care services and highlight areas for further research. There are, however, a number of methodological issues that could have a bearing on the validity of the results. Owing to a lack of evidence in this area we included all studies types including uncontrolled studies. Only four of our included studies were randomised controlled trials. Whilst uncontrolled studies might be more likely to be biased these broad inclusion criteria enabled us to investigate integrated working more widely and identify barriers and facilitators.

Although the studies reviewed were judged to have involved integrated working, it was not their main focus; only two studies referred to partnership working between care homes and health care services (Goodman, C et al: Can clinical benchmarking improve bowel care in care homes for older people? Final report submitted to the DoH Nursing Quality Research Initiative PRP, Centre for Research in Primary and Community Care, University of Hertfordshire, 2007.)[44]. The information on integrated working was based on how the intervention was described, who was involved and at what level. It is possible that how this was reported in the studies reviewed did not capture the extent of the integration achieved.

Conclusions

Integrated working aims to ensure continuity of care, reduce duplication and fragmentation of services and places the patient as the focus for service delivery. This review identified a limited number of studies where the intervention supported integrated working between care homes and primary health care professionals. The narrow focus and single issue orientation of the majority of the studies did not engage with the needs of care home population or the context and organisation of their care. Outcome measures reflected the priorities of health care professionals rather than residents and care home staff. In view of the growing demand for residential and nursing home care together with funding constraints, more effective working between the NHS and care home providers is essential. There is an urgent need to develop and test interventions that promote integrated working and address the persistent divide between health services and independent providers.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Institute for Health Research Service Delivery and Organisation programme (project number 08/1809/231).

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NIHR SDO programme or the Department of Health.

References

Department of Health: The Health Act, implemented in England and Wales in 2000. 1999, Department of Health

Department of Health: The Commissioning Framework for Health and Well-being. 2007, Department of Health

Laing and Buisson: Care of elderly people UK market survey 2009. 2009, London

Care Quality Commission: The quality and capacity of adult social care services: an overview of the adult social care market in England 2008/2009. 2009

Jacobs S, Alborz A, Glendinning C, Hann M: Health services for homes. A survey of access to NHS services in nursing and residential homes for older people in England. 2001, NPCRDC, University of Manchester

Glendinning C, Jacobs S, Alborz A, Hann M: A survey of access to medical services in nursing and residential homes in England. British Journal of General Practice. 2002, 52 (480): 545-549.

Goodman C, Woolley R, Knight D: District nurses' experiences of providing care in residential care home settings. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2003, 12: 67-76. 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2003.00678.x.

Goodman C, Robb N, Drennnan V, Woolley R: Partnership working by default district nurses and care home staff providing care for older people. Health Soc Care Community. 2005, 13 (6): 553-62. 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2005.00587.x.

Alzheimer's Society: Home from home: quality of care for people with dementia living in care homes. 2007, Alzheimer's Society London

Department of Health: Dignity in Care: Practice Guide. 2007, Department of Health

Department of Health: End of Life care strategy - promoting high quality care for all adults at the end of life. 2008, London. DoH

Owen , et al: Better partnership between care homes and the NHS: findings from the My Home Life programme. Journal of Care Services Management. 2008, 3 (1): 96-106.

Goodman C, Woolley R: Older people in care homes and the primary care nursing contribution: a review of relevant research. Primary Health Care Research and Development. 2004, 5: 179-187. 10.1191/1463423604pc199oa.

Joseph Rowntree Foundation: Providing nursing support within residential care homes. 2008, JRF ISSN 0958-3084. (Summary based on research from two interim reports. Wild D et al. The In-reach model described from the perspectives of stakeholders, home managers, care staff and the In-reach team. (May2007) University of West of England)

Kavanagh and Knapp: The impact on general practitioners of the changing balance of care for elderly people living in institutions. British Medical Journal. 1998, 317 (7154): 322-7. 10.1136/bmj.317.7154.322.

Royal College of Physicians, Royal College of Nursing and British Geriatrics Society: The health and care of older people in care homes - a comprehensive interdisciplinary approach. 2001, London: Royal College of Physicians of London

Kayser Jones J, Schell E, Lyons W, et al: Factors that influence end-of-life care in care homes: the physical environment, inadequate staffing, and lack of supervision. Gerontologist. 2003, 76-84. 2

Mozeley C, Sutcliffe C, Bagley H, et al: Towards Quality Care: outcomes for older people in care homes. 2004, PSSRU Ashgate, Aldershot

Perry M, Carpenter I, Challis D, Hope K: Understanding the roles of registered general nurses and care assistants in care homes. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2004, 42 (5): 497-505.

Ham C: 'The ten characteristics of the high-performing chronic care system'. Health Economics, Policy and Law. 2010, 5: 71-90. 10.1017/S1744133109990120.

Kings Fund: How to deliver high-quality, patient-centred, cost-effective care Consensus solutions from the voluntary sector. 2010, London Kings Fund

Rosen R, Ham C: Integrated Care: Lessons from Evidence and Experience. 2008, The Nuffield Trust for Research and Policy Studies in Health Services

Kodner DL, Spreeuwenberg C: Integrated care: meaning, logic, applications, and implications - a discussion paper. International journal of integrated care. 2002, 2 (1): 1-6.

Bond J, Gregson BA, Atkinson A: Measurement of Outcomes within a Multicentred Randomized Controlled Trial in the Evaluation of the Experimental NHS Nursing Homes. Age and Ageing. 1989, 18: 292-302. 10.1093/ageing/18.5.292.

British Geriatrics Society: The Teaching Care Home - an option for professional training. Proceedings of a Joint BGS and RSAS AgeCare Conference held in February 1999. 1999, accessed 080311, [http://www.bgs.org.uk/PDF%20Downloads/teaching_care_homes.pdf]

Higgins JPT, Green S, editors: Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions 5.0.0. [updated February 2008]

Spencer L, Ritchie J, Lewis J, Dillon L: Quality in Qualitative Evaluation: A Framework for Assessing Research Evidence. 2003, Government Chief Social Researcher's Office: London

Spencer, Richie : Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. Analysing qualitative data. Edited by: Bryman A, Burgess RG. 1994, London and New York Routledge, 172-194.

Avis M, Greening Jackson J, Cox K, Miskella C: Evaluation of a project providing palliative care support to nursing homes. Health and Social Care in the Community. 1999, 7 (1): 32-38. 10.1046/j.1365-2524.1999.00158.x.

Hockley J, Dewar B, Watson J: Promoting end-of-life care in nursing homes using an 'integrated care pathway for the last days of life'. Journal of Research in Nursing. 2005, 10 (2): 135-152. 10.1177/174498710501000209.

Mathews M, Finch J: Using the Liverpool Care Pathway in a nursing home. Nursing Times. 2006, 102 (37): 34-35.

Knight G, Jordan C: All-Wales integrated care pathway project for care homes: completing the audit cycle - retrospective baseline audit findings of documented care during the last days of life of residents who died in care homes and the re-audit findings following implementation of the ICP. Journal of integrated care pathways. 2007, 11: 112-119.

Hasson F, Kernohan G, Waldron M, Whittaker E, McLaughlin D: The palliative care link nurse role in nursing homes: barriers and facilitators. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2008, 233-242.

Vu T, Harris A, Duncan G, Sussman G: Cost-effectiveness of multidisciplinary wound care in nursing homes: a pseudo-randomized pragmatic cluster trial. Family Practice Advanced Access. 2007, 372-379.

Opie J, Doyle C, Connor DW: Challenging behaviours in nursing home residents with dementia: a randomized controlled trial of multidisciplinary interventions. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2002, 17: 6-13. 10.1002/gps.493.

Llewellyn-Jones RH, Baikie KA, Smithers H, Cohen J, Snowdon J, Tennant CC: Multifaceted shared care intervention for late life depression in residential care: randomised controlled trial. British Medical Journal. 1999, 319: 676-82. 10.1136/bmj.319.7211.676.

Proctor R, Stratton Powel H, Burns A, Tarrier N, Reeves D, Emerson E, Hatton C: An observational study to evaluate the impact of a specialist outreach team on the quality of care in nursing and residential homes. Aging and Mental Health. 1998, 2 (3): 232-238. 10.1080/13607869856713.

Schmidt I, Claesson CB, Westerholm B, Nilsson LG, Svarstad BL: The impact of Regular Multidisciplinary Team Interventions on Psychotropic Prescribing in Swedish Nursing Homes. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1998, 46: 77-82.

Crotty M, Halbert J, Rowett D, Giles L, Birks R, Williams H, Whitehead C: An outreach geriatric medication advisory service in residential aged care: a randomised controlled trial of case conferencing. Age and Ageing. 2004, 33: 612-617. 10.1093/ageing/afh213.

King M, Roberts MS: Multidisciplinary case conference reviews: improving outcomes for nursing home residents, carers and health professionals. Pharmacy World and Science. 2001, 23: 41-4. 10.1023/A:1011215008000.

Szczepura A, Nelson S, Wild D: In-reach specialist nursing teams for residential care homes: uptake of services, impact on care provision and cost-effectiveness. BMC Health Services Research. 2008, 8: 269-10.1186/1472-6963-8-269.

Doherty D, et al: Examining the impact of a specialist care homes support team. Nursing Standard. 2008, 23 (5): 35-41.

Joseph A, Boult C: Managed Primary Care of Nursing Home Residents. Journal of the American Geriatric Society. 1998, 46: 1152-1156.

Kane RL, Flood S, Bershadsky B, Keckhafer G: Effect of an Innovative Medicare Managed Care Program on the Quality of Care for Nursing Home Residents. The Gerontological Society of America. 2004, 44 (1): 95-103.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6963/11/320/prepub

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

All authors declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Authors' contributions

CG, FB, SI, KF designed the protocol, SD, FB, CG, CV, KF screened literature, reviewed papers for inclusion, extracted data and wrote the paper. All authors interpreted data, critically reviewed the paper and have approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Davies, S.L., Goodman, C., Bunn, F. et al. A systematic review of integrated working between care homes and health care services. BMC Health Serv Res 11, 320 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-11-320

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-11-320