Abstract

Background

Promoting cycling to school may benefit establishing a lifelong physical activity routine. This systematic review aimed to summarize the evidence on strategies and effects of school-based interventions focusing on increasing active school transport by bicycle.

Methods

A literature search based on “PICo” was conducted in eight electronic databases. Randomized and non-randomized controlled trials with primary/secondary school students of all ages were included that conducted pre-post measurements of a school-based intervention aimed at promoting active school travel by bicycle and were published in English between 2000 and 2019. The methodological quality was assessed using the “Effective Public Health Practice Project” tool for quantitative studies. Applied behavior change techniques were identified using the “BCT Taxonomy v1”. Two independent researchers undertook the screening, data extraction, appraisal of study quality, and behavior change techniques.

Results

Nine studies investigating seven unique interventions performed between 2012 and 2018 were included. All studies were rated as weak quality. The narrative synthesis identified 19 applied behavior change techniques clustered in eleven main groups according to their similarities and a variety of 35 different outcome variables classified into seven main groups. Most outcomes were related to active school travel and psychosocial factors, followed by physical fitness, physical activity levels, weight status, active travel and cycling skills. Four studies, examining in total nine different outcomes, found a significant effect in favor of the intervention group on bicycle trips to school (boys only), percentage of daily cycling trips to school, parental/child self-efficacy, parental outcome expectations, moderate-to-vigorous intensity physical activity (total, from cycling, before/after school), and total basic cycling skills. Seven of these outcomes were only examined in two studies conducting the same intervention in children, a voluntary bicycle train to/from school accompanied by adults, including the following clustered main groups of behavior change techniques: shaping knowledge, comparison of behavior, repetition and substitution as well as antecedents.

Conclusions

The applied strategies in a bicycle train intervention among children indicated great potential to increase cycling to school. Our findings provide relevant insights for the design and implementation of future school-based interventions targeting active school transport by bicycle.

Trial registration

This systematic review has been registered in the international prospective register of systematic reviews “PROSPERO” at (registration number: CRD42019125192).

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

There is increasing focus on identifying effective strategies to improve physical activity (PA) among children and adolescents [1]. Most young people in Europe do not achieve the recommended daily accumulation of 60 min (min) in moderate-to-vigorous intensity physical activity (MVPA) [2] of the World Health Organization (WHO) [3], in spite of the well-known health benefits [4]. Both PA-related health benefits, which can persist into adult life, and a variety of health problems in adulthood, including overweight or obesity [5], appear to have their origin in early life [5, 6]. Therefore, the low compliance with PA recommendations is alarming. Since PA habits are established early in life, promoting PA from an early age is required [7,8,9,10,11]. Active school travel (AST) is a source of habitual PA for students and therefore highly recommended [12]. AST is positively related to total daily PA [13,14,15,16], school day PA [14, 17] as well as PA before and after school [14, 15, 17]. Cycling is an important option for AST. In England, those who cycled for AST accumulated on average 1.4 h of cycling per week, which contributed 20% of recommended weekly PA [16]. As a result, a higher percentage of cyclists (36%) aged 5 to 15 years meet the weekly WHO recommendation of PA compared to walkers (25%) and those who did not walk or cycle to/from school (22%) [16]. In particular, adolescent girls, who have lower levels of PA [18] and perceive more barriers to PA (e.g., lack of energy) [19], may benefit more from participating in AST than adolescent boys [14]. Previous research showed that adolescent girls from New Zealand who participated in AST were more likely to meet the PA recommendations compared to passive travelers [14]. This was not the case for boys [14].

In addition, AST has been positively associated with body composition [15, 20], positive emotions [21], and cognitive performance (only in adolescent girls) [22]. Compared to walking, cycling is generally of higher intensity [23]. Thereby, AST by bicycle contributes to cardiovascular fitness [23] and may reduce the future risk of cardiovascular diseases. In addition, AST has been positively associated with environmental factors, such as reduction of traffic [24, 25] which contributes to a minimization of air pollution [23, 25] and enhancement of road safety [24]. Furthermore, adopting a daily AST routine including journeys to and from school [26] as early as possible may lead to a potentially lifelong habit of active transport (AT) [16] including journeys to any other destination. Moreover, a study in Ireland showed that AST by bicycle increases the mobility of adolescents living further away from school [27]. Bicycles are also the fastest means of transportation for distances less than 5 km in cities, especially when car traffic is congested [28].

Studies in Germany showed that most children and adolescents aged up to 17 years own a bicycle (57 to 98%) [29]. However, only 8% [30] to 22.2% [31] cycle to/from school daily or usually. Additionally, more boys (23.8%) than girls (20.6%) cycle to school in Germany [31]. In the Czech Republic, the percentages of boys (5.7, 3.2, 2.2%) and girls (2.3, 0.5, 2%) aged 11 to 15 years who cycled to/from school between 2006, 2010 and 2014 decreased over time [32]. According to these data from Germany and the Czech Republic, cycling is a less common form of AST, cycling habits differ by gender in favor of boys, and there might be a declining trend in some European countries.

Following this, researchers have increased interest in developing AST interventions in the last years [33]. A previous systematic review focused on the effects of AST interventions aiming to promote walking [24]. No previous systematic review dealt exclusively with the effectiveness of intervention strategies targeting cycling as means of AST, which is required for adequate policy decisions in this field [1]. Thus, the aims of this systematic review were to summarize the evidence on strategies and effects of (randomized) controlled interventions that promote cycling to school as a mode of AST among primary and/or secondary school students.

Methods

The methodological procedure of this systematic review is described in detail elsewhere [34]. For drafting this systematic review, the checklist “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement” [35] (see Additional file 1) was utilized.

Inclusion criteria

In this systematic review, (parallel-group or cluster-randomized) controlled trials (RCTs; CTs) were considered that described a school-based bicycle intervention fostering the use of bicycles in AST. Only samples that represented primary and/or secondary school students were included. The control group (CG) could be either active in terms of getting an alternative intervention program without strategies promoting AST or not receiving any kind of intervention. Only studies published in English and, due to current relevance, between 2000 and 2019 were included.

Search strategy

A comprehensive search formula with a combination of keywords in three different categories according to “PICo” (population, intervention, context) [36] was generated in collaboration with two specialists (see Additional file 2). The first literature search based on title and abstract was conducted on November 28th, 2018 and was updated on November 25th, 2019 in eight electronic databases (ERIC: EBSCO, PsycINFO: EBSCO, PSYNDEX: EBSCO, PubMed: NCBI, Scopus: ELSEVIER, SPORTDiscus: EBSCO, SURF: BISp, and Web of Science: Clarivate Analytics).

Study selection

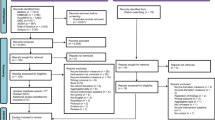

Records were imported into and further managed with EndNote X7.4. The identified articles were screened independently by DS and TA/AM based on title, abstract, and full text in terms of their relevance and depicted in a flow chart (see Fig. 1). Any disagreements between the reviewers during these three steps of the selection process were resolved by discussion.

Data extraction

Data regarding general study details, characteristics of participants, theoretical background, intervention description, outcome variables, measuring instruments, statistical analysis, and results were extracted using a previously piloted data extraction spreadsheet. Due to relevance, only intervention components that directly targeted AST were extracted. The authors of the included studies were contacted via e-mail with a maximum of two reminders if relevant data was missing or a clarification of descriptions was required. Therefore, the data extractors (DS and TA/AM) were not blinded to authors and journals while extracting study information. Two evaluators (DS and TA) independently coded the behavior change techniques (BCTs) applied to intervention components using the “BCT Taxonomy v1” [37]. Intervention components which could not be assigned to the 93 BCTs originally clustered in 16 main groups were classified into two newly added strategies/groups (i.e., knowledge transfer and parental involvement) by the authors according to a previously-used procedure [38]. Therefore, strategies were classified within a taxonomy of 95 BCTs clustered in 18 main groups. Any discrepancies were resolved by discussion.

Quality assessment

For the assessment of the methodological quality of included studies, the quality assessment tool for quantitative studies “Effective Public Health Practice Project” (EPHPP) [39] was used. Where an explicit reference to a joint, more detailed article (e.g., study protocol) was mentioned, this article was additionally used to complete the assessment of the study’s methodological quality. Otherwise, articles in which the same intervention was analyzed with regard to different outcomes were assessed independently. A critical judgment was made for all items within the following eight quality sections/components (see Additional file 3): (A) Selection bias (two items), (B) Study design (four items), (C) Confounders (three items), (D) Blinding (two items), (E) Data collection methods (depending on the number of collected variables), (F) Withdrawals/Drop-outs (two items), (G) Intervention integrity (three items), and (H) Analyses (four items). Each item within the eight sections was assessed as strong, moderate or weak. The methodological quality of each item was rated independently by DS and TA/AM. Discrepancies between the evaluators despite discussions were resolved by consulting another independent evaluator (YD).

The following modifications to the EPHPP dictionary were made: Regarding the section (C) “confounders”, eight potentially relevant variables were chosen (i.e., age, sex/gender, previous AST experiences at baseline level, weight status, migration background, bicycle ownership, socio-economic status, distance from home to school) based on the “Model of Childrenʼs Active Travel” (M-CAT) [40]. When studies included five to eight of these potentially relevant variables as confounders, this item was rated as strong. It was rated as moderate when only three to four of potentially relevant variables were included and it was rated as weak when less than two of potentially relevant variables were included. In a further item of this section C, the quality of confounders was rated. If relevant to the study, the consideration of “sex/gender” [32] and “migration background” [31] led to a strong rating, whereas including “age” [32, 41] and “previous AST experience at baseline level” [42, 43] in the analysis were rated as moderate (weak: the rest). In the section (G) “intervention integrity”, the (unclear) presence of any kind of co-intervention or contamination led to a weak rating (strong: no co-intervention/contamination). Within the section (H) “analyses”, the item “unit of allocation” was rated as strong for “school”, as moderate for “class”, and as weak for “individual” based on the randomization level. The “unit of analysis” was appropriate and determined as strong when analyses were adjusted according to the “unit of allocation”. This means, for example, that analyses of a study cluster-randomized at school level had to be adjusted for schools. Otherwise, the “unit of analysis” was not appropriate and rated as weak.

After rating the individual items, each of the eight EPHPP quality components were assessed as a) strong (no weak ratings and more strong than moderate ratings), b) moderate (one weak rating), and c) weak (at least two weak ratings). Finally, a global quality rating based on the eight EPHPP components in each study was performed according to a common procedure [38]. When five or more components were assessed as strong and no components were assessed as weak, the global quality of a study was rated as strong [38]. The global quality of a study was rated as moderate when at least four components were assessed as strong and no more than one component was assessed as weak [38]. A weak methodological quality was rated when two or more components were assessed as weak [38].

Data synthesis

All findings were summarized narratively by reporting effect sizes (ES), like Cohen’s d, Odds Ratio, partial Eta-squared (\( {\upeta}_{\mathrm{p}}^2 \)), and effect estimates, like confidence intervals (CI), or p-values (significant: p ≤ 0.05). The various outcome variables were grouped and studies were marked according to their effectiveness in terms of changing the related outcome(s). Results were sorted by age group (children up to the age of 12 years; adolescents from 13 years of age) [2]. If data allowed, gender effects were reported. Against our previous intention described in the published protocol [34], it was not possible to describe cultural dynamics based on regional differences. Given that only one outcome, i.e., body-mass-index (BMI), was considered in more than one intervention and measured/classified identically [44, 45], heterogeneity of variables across reviewed studies did not permit to carry out meta-analyses for intervention effects.

Results

In total, 1711 publications were found in the first search and another 208 publications in the updated search. After removal of 776 duplicates, 1143 articles were screened. Nine relevant studies evaluating seven unique interventions were included in this review [44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52].

Intervention characteristics and BCTs

The characteristics of the seven included interventions, evaluated in nine studies between 2012 and 2018, were heterogeneous (see Table 1). Interventions were carried out either in Europe (n = 5) or the USA (n = 2). Four interventions were designed as RCT. Only in three interventions, a sample size calculation was performed. Six out of seven interventions reported a sample size at baseline and indicated a range from 53 to 2401 participants. The number of recruited schools ranged from 1 to 25 (1 to 5 schools: n = 4; 14 schools: n = 1; 25 schools: n = 1). Primary schools and two grade levels were the most frequently chosen settings. The age of participants was up to 17 years (children: n = 4, children and adolescents: n = 3). Only five interventions reported the gender ratio of girls and boys. Interventions lasted between 4 weeks and 1 year and were classified into short-term (≤3 months: n = 3) or moderate-term (4 to 12 months: n = 2). Only one intervention included two different intervention arms (with/without parental involvement). Five interventions clearly stated that they did not deliver any kind of intervention to the CG. Three of these interventions, however, described either a provision of information (n = 1) or some kind of contamination in terms of minor interventions or similar conditions between the intervention group (IG) and CG (n = 2). Two interventions did not clearly report the conditions of the CG but mentioned contaminations, such as minor interventions, or delivery of informational letters. Three interventions reported that components were based on established theoretical frameworks, including the “Conceptual framework of AT in children”, the “Active Living by Design: 5P model” and the “Social Cognitive Theory”. One intervention was inspired by several correlates of cycling to school. In three interventions, no theoretical model was mentioned as a basis. The interventions included different components, such as a cycle training course or a bicycle train (i.e., adult-guided group of cycling children). Six interventions used a multicomponent approach with a combination of environmental, informational and behavioral (n = 2), environmental and informational (n = 1) or informational and behavioral (n = 3) components. One intervention was based on a behavioral approach only. Each intervention component was at least linked to one BCT. In total, 19 different applied BCTs were identified across the seven interventions.

These 19 different applied BCTs were clustered in a total of 11 out of 18 main groups (see Table 2), which varied in their popularity: (1) Shaping knowledge (n = 6), (2) Comparison of behavior (n = 5), (3) Repetition and substitution (n = 5), (4) Antecedents (n = 4), (5) Social support (n = 3), (6) Parental involvement (n = 3), (7) Natural consequences (n = 2), (8) Knowledge transfer (n = 2), (9) Feedback and monitoring (n = 1), (10) Reward and threat (n = 1), (11) Goals and planning (n = 1). The seven interventions used in average 4.7 main groups.

Study quality

All included studies were assessed as weak in the global rating but none of the nine studies had a weak rating in all eight sections (see Table 3).

Figure 2 gives an overview of the study quality for individual sections across all reviewed studies. Due to the inclusion of RCTs and CTs only, the section with the strongest methodological quality was “study design” rated as strong in all nine studies. Additional strong ratings were found in the sections “confounders”, “data collection methods”, “withdrawals/drop-outs”, and “analyses”. In the section “confounders”, only one study [48] did not report adjustments. The other eight studies [44,45,46,47, 49,50,51,52] reported adjustments for at least two up to eight out of ten different covariates (i.e., age, distance from home to school, sex/gender, AST, BMI, race, bike score, neighbourhood disorder, attendance, accelerometer wear time). However, group differences at baseline were only absent in two studies [44, 51]. In the section “data collection methods”, three studies were rated as weak [45, 46, 51], three as moderate [47, 48, 52], and three as strong [44, 49, 50]. Referring to the section “withdrawals/drop-outs”, six studies declared drop-outs [44, 46, 47, 50,51,52] and five studies had low retention rates [45, 48, 49, 51, 52]. The sections “selection bias” and “blinding” were never rated as strong. Apart from two studies [46, 48], seven studies did not report the representativeness of the sample. Six studies [45,46,47, 50,51,52] reached a high recruitment rate. All but one study [44] either did not report blinding at all or reported unblinded conditions. In the section “analyses” ratings were either strong [46, 49, 50, 52] or weak [44, 45, 47, 48, 51] with strengths in the unit of allocation [45,46,47, 49,50,51,52] as well as statistical methods (including ES) [44,45,46, 48,49,50, 52] and deficits in the unit of analyses [45, 47, 48, 51] as well as usage of intention-to-treat analysis [44, 45, 47, 48, 51].

The weakest section was “intervention integrity” rated as weak in all nine studies. Only one study [45] indicated the percentage of intervention delivery and measurement of consistency. Moreover, six out of nine studies [44,45,46, 48,49,50] described a potential contamination in the CG.

Intervention effects

Altogether, six studies reported proportionally more non-significant than significant intervention effects [44,45,46,47,48, 51]. One study found more adverse intervention effects in boys with larger improvements in the CG [52]. Only two studies – describing the same intervention in children: a “bicycle train” to actively travel to school – showed significant beneficial intervention effects in all their seven outcomes [49, 50] (see Tables 4 and 5).

In total, 35 different outcome variables were reported across the nine included studies. These 35 outcome variables were clustered in seven main outcome groups: (1) AST (n = 9), (2) Psychosocial factors targeting both parents or students (n = 9), (3) Physical fitness divided into cardiorespiratory/muscular fitness and speed agility (n = 8), (4) PA levels (n = 4), (5) Weight status (n = 3), (6) AT (n = 1), and (7) Cycling skills (n = 1).

A significant intervention effect was found on 13 different outcomes analyzed across five studies [45, 47, 49, 50, 52], whereas seven studies reported non-significant effects on 25 outcomes in total [44,45,46,47,48, 51, 52]. Within the outcome group “AST”, one study found a significant beneficial intervention effect on bicycle trips to school by boys [52] and another study on percentage of daily cycling trips to school (β = 44.9 [CI95: 26.8, 63.0]) [50]. One study, investigating psychosocial factors only, showed significant beneficial intervention effects on parental (β = 0.46 [CI95: 0.05, 0.86]) and child self-efficacy (β = 0.84 [CI95: 0.37, 1.31]) as well as parental outcome expectations (β = 0.47 [CI95: 0.17, 0.76]) [49]. Within the outcome group “physical fitness”, one study found a significant adverse intervention effect on aerobic capacity with an unfavorable development in the IG (β = − 1.45 [CI95: − 1.92, − 1.00]) [45]. Another study found significantly higher values in the CG for boys only on VO2max (group main effect: \( {\eta}_{\mathrm{p}}^2=0.01 \)), 20-m shuttle run test (group main effect: \( {\eta}_{\mathrm{p}}^2=0.04 \)), and handgrip strength [52]. Within the outcome group “PA levels”, one study reported positive intervention effects on total MVPA (β = 21.6 [CI95: 8.7, 34.6]), MVPA from cycling (β = 23.0 [CI95: 10.7, 35.4]) and MVPA before/after school (β = 12.8 [CI95: 8.5, 17.2]) [50]. One study found a significant intervention effect on total basic cycling skills in both intervention arms (with/without parental involvement), which were taken together in this analysis [47].

The sustainability of intervention effects were examined in only two studies at 5- [47] or 6-month follow-up [51]. After participating in a 4-week cycle training course, a significant intervention effect from pre to post to follow-up for both intervention arms (with/without parental involvement) was found on total basic cycling skills but neither on cycling to school (in min) nor on parental attitudes towards cycling [47]. Significant effects at 6-month follow-up were found on “mode of trips to school” in walking only and “frequency of active trips to school” (walking/cycling) even though non-significant intervention effects from pre to post after 6 months were shown on these variables [51].

Discussion

The aims of this systematic review were to provide an overview of existing school-based interventions focusing on the promotion of AST by bicycle in children and adolescents and their evidence on strategies and effects. Following our inclusion criterion for study designs, we only found a small number of (R)CTs in our literature search. This is consistent with the reported gap of strong study designs in this research field [53]. The included trials were predominantly not conducted in cycle-centric countries within Europe (exception: Belgium (n = 1) and Denmark (n = 2)) [54], showed a large variety of components and outcome measures, and were of weak quality. Three of the included trials did not differentiate between walking and cycling as two different types of AST in their analyses [46, 48, 51, 52]. Therefore, a final conclusion on cycling to school could not be drawn from these studies. Additionally, the reported interventions were designed for children only or both children and adolescents, implemented in primary schools. The lack of interventions for adolescents, implemented in secondary schools, is also in line with the current state of research [55]. In conclusion, the findings of our systematic review need to be interpreted with caution.

Promising intervention strategies

Overall, only one intervention using a single-component approach showed consistent positive effects on all measured outcome variables [49, 50] and provides first insights into an effective intervention strategy. For approximately 2 months, a voluntary and adult-guided bicycle train to/from school with pick up/drop off stops was provided for children on schooldays [49, 50] including the following main groups of BCTs: shaping knowledge, comparison of behavior, repetition and substitution as well as antecedents. The counterpart of a bicycle train, the “walking school bus” (WSB), is based on a similar approach for walking. In a previous review, the WSB was found to increase walking to school as well as general PA levels in children [24]. However, the bicycle train intervention effect on MVPA from cycling (23.0 min/day) was higher than the intervention effect on total MVPA (21.6 min/day) [50]. This accelerometer data might suggest a compensation in total MVPA due to the additional MVPA from AST by bicycle.

The only study that performed a sex/gender analysis reported increased bicycle trips to school in boys but not in girls [52]. As boys had higher levels of health-related fitness than girls despite comparable low cycling to school rates at baseline [52], poor fitness could be a barrier to uptake AST by bicycle in girls. More research on the existence and explanation of gender differences in intervention effects is warranted in future studies to draw final conclusions.

Strengths/limitations

The major strengths of this systematic review are the specific focus on school-based interventions that promote cycling to school and including only (R)CTs, which provide a higher evidence level than other study designs [56]. Two researchers independently conducted the process of selecting studies, extracting data, evaluating methodological quality and BCTs. Furthermore, authors of included studies were contacted in case of missing data to avoid an underestimation of the methodological quality. Finally, findings were interpreted separately from the methodological quality rating in order to provide transparency.

A limitation is that the defined criterion of including only (R)CTs could have led to a selection bias [53]. The same applies to the restriction of studies published in English. At study level, there are several reasons for a lack of effectiveness. One reason could be the complete absence of intervention periods longer than 13 months [57]. According to the “Transtheoretical Model of Behavior Change”, “individuals may need to go through a number of stages associated with the formulation and implementation of attitudes and beliefs before actually undertaking changes, and this whole process takes some time” [58] (p. 68). This is why a lack of immediate success in short- or moderate-term interventions might not necessarily indicate a failure of the intervention [59]. The adoption and integration of cycling to school into the daily routine could have happened after the observed period. Another reason for a lack of effectiveness could be that different local needs in terms of barriers to cycle to school were not sufficiently addressed in interventions [60]. In a previous study, barriers of AST in general were categorized according to the “Social-ecological model of the correlates of AT” [61]: intrapersonal/individual (i.e., child factors), interpersonal (e.g., parental factors), community (e.g., school policy), and environment (e.g., traffic) [62]. One multicomponent intervention among children was inspired by correlates of cycling to school considering such barriers (e.g., intrapersonal/individual including motivation by competitions and safety by cycle training, interpersonal including parental involvement, community including school policies, and environmental changes including traffic regulation) and used almost the same BCTs as the effective bicycle train intervention (apart from repetition and substitution including behavior substitution, habit formation, habit reversal) [45]. Despite this, this intervention was not effective on any outcome in favor of the IG [45]. Furthermore, the improvement of basic cycling skills in a cycle training program among children (examined in only one intervention) without practicing traffic-related skills in the natural environment may be insufficient to impact AST by bicycle [47]. Moreover, a cycle training program including parental assisted homework tasks (e.g., identification of the safest school cycling route and the most dangerous traffic spots close to the school) after each cycle training failed to find effective ways of involving parents as an intervention strategy [47]. The reason could be that the homework tasks insufficiently addressed or increased personal safety barriers in parents (e.g., fears, dangers, concerns about the child’s behavior in road traffic) [62]. This may have blocked behavior change in their child as the influence of parents on AST is higher among children than adolescents [40]. Therefore, adolescents may need different intervention strategies than children because all five studies that effectively influenced 13 of 24 examined outcomes included children only [45, 47, 49, 50, 52] and three of the four studies that were not effective in influencing any outcome included both children as well as adolescents [44, 46, 48]. To adequately tailor interventions to a specific population, we recommend following a systematic approach when developing interventions (e.g., the “Intervention Mapping Approach” including a comprehensive needs assessment and theoretical frameworks [63]). Moreover, we recommend conducting a process evaluation that provides insights into the implementation of the intervention (e.g., feedback on program and material, (dis)satisfaction). In addition, we recommend using a checklist when reporting the study. Adherence to the planned intervention (e.g., delivered intensity) was lacking in the majority of studies although “the dose of an intervention is a key predictor of behavior change” [58] (p. 68). Furthermore, contamination was quite common and could have caused an underestimation of effects. Finally, interpretations of findings could be biased due to group differences at baseline.

Conclusions

As a result of the heterogeneity and low methodological quality of included studies, we conclude that the evidence for the effectiveness of interventions promoting AST by bicycle is insufficient. Therewith, our findings confirm that this research field is still in an early development stage [57]. Nevertheless, there is an indication that a bicycle train to/from school among children in primary school, including four clustered main groups of BCTs (shaping knowledge, comparison of behavior, repetition and substitution as well as antecedents), is a promising intervention. More research is needed to better understand strategies and effects of school-based interventions promoting AST by bicycle, especially among adolescents in secondary school.

Based on the findings of this systematic review, there is a need for high-quality intervention studies in this research field. This is why future studies are recommended to evaluate theory-based interventions in longer-term (R)CTs using relevant, valid and reliable outcome measures. Additionally, more research is warranted to examine the moderating effect of gender in AST interventions by bicycle and to prove long-term maintenance of behavior change.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- AST:

-

Active school travel

- AT:

-

Active transport

- β:

-

Beta coefficient

- BCT(s):

-

Behavior change technique(s)

- BMI:

-

Body-mass-index

- CG:

-

Control group

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CT(s):

-

Controlled trial(s)

- e.g.:

-

For example

- EPHPP:

-

Effective Public Health Practice Project

- ES:

-

Effect size(s)

- h:

-

hour(s)

- i.e.:

-

That is

- IG:

-

Intervention group

- m:

-

Meter(s)

- M-CAT:

-

Model of Childrenʼs Active Travel

- min:

-

Minute(s)

- MVPA:

-

Moderate-to-vigorous intensity physical activity

- n:

-

Number(s)

- p:

-

Probability value

- PA:

-

Physical activity

- PICo:

-

Population, interest, context

- RCT(s):

-

Randomized controlled trial(s)

- VO2max:

-

Maximal oxygen uptake

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- WSB:

-

Walking school bus

References

Messing S, Rütten A, Abu-Omar K, Ungerer-Röhrich U, Goodwin L, Burlacu I, et al. How can physical activity be promoted among children and adolescents? A systematic review of reviews across settings. Front Public Health. 2019. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2019.00055.

Van Hecke L, Loyen A, Verloigne M, van der Ploeg HP, Lakerveld J, Brug J, et al. Variation in population levels of physical activity in European children and adolescents according to cross-European studies: a systematic literature review within DEDIPAC. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-016-0396-4.

World Health Organization (WHO). Global recommendations on physical activity for health. Geneva: WHO Press; 2010.

Poitras VJ, Gray CE, Borghese MM, Carson V, Chaput J-P, Janssen I, et al. Systematic review of the relationships between objectively measured physical activity and health indicators in school-aged children and youth. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1139/apnm-2015-0663.

Cavill N. Children and young people – the importance of physical activity. A paper published in the context of the European heart health initiative. Brussels: European Hearth Network; 2001.

Beneke R, Leithäuser RM. Körperliche Aktivität im Kindesalter – Messverfahren. Dtsch Z Sportmed. 2008;59:215–22.

Telama R, Leskinen E, Yang X. Stability of habitual physical activity and sport participation: a longitudinal tracking study. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 1996. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0838.1996.tb00109.x.

Telama R, Yang X, Viikari J, Välimäki I, Wanne O, Raitakari O. Physical activity from childhood to adulthood: a 21-year tracking study. Am J Prev Med. 2005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2004.12.003.

Telama R. Tracking of physical activity from childhood to adulthood: a review. Obes Facts. 2009. https://doi.org/10.1159/000222244.

Telama R, Yang X, Leskinen E, Kankaanpää A, Hirvensalo M, Tammelin T, et al. Tracking of physical activity from early childhood through youth into adulthood. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000000181.

Trudeau F, Laurencelle L, Shephard RJ. Tracking of physical activity from childhood to adulthood. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004. https://doi.org/10.1249/01.MSS.0000145525.29140.3B.

Institute of Medicine (IOM). Educating the student body: taking physical activity and physical education to school. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2013.

Faulkner GEJ, Buliung RN, Flora PK, Fusco C. Active school transport, physical activity levels and body weight of children and youth: a systematic review. Prev Med. 2009. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.10.017.

Kek CC, García Bengoechea E, Spence JC, Mandic S. The relationship between transport-to-school habits and physical activity in a sample of New Zealand adolescents. J Sport Health Sci. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2019.02.006.

Mendoza JA, Watson K, Nguyen N, Cerin E, Baranowski T, Nicklas TA. Active commuting to school and association with physical activity and adiposity among US youth. J Phys Act Health. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.8.4.488.

Roth MA, Millett CJ, Mindell JS. The contribution of active travel (walking and cycling) in children to overall physical activity levels: a national cross sectional study. Prev Med. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.12.004.

Sirard JR, Riner WF, McIver KL, Pate RR. Physical activity and active commuting to elementary school. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2005. https://doi.org/10.1249/01.mss.0000179102.17183.6b.

Guthold R, Stevens GA, Riley LM, Bull FC. Global trends in insufficient physical activity among adolescents: a pooled analysis of 298 population-based surveys with 1·6 million participants. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(19)30323-2.

Rosselli M, Ermini E, Tosi B, Boddi M, Stefani L, Toncelli L, et al. Gender differences in barriers to physical activity among adolescents. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.numecd.2020.05.005.

Lubans DR, Boreham CA, Kelly P, Foster CE. The relationship between active travel to school and health-related fitness in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-8-5.

Ramanathan S, O'Brien C, Faulkner G, Stone M. Happiness in motion: emotions, well-being, and active school travel. J Sch Health. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12172.

Martínez-Gómez D, Ruiz JR, Gómez-Martínez S, Chillón P, Rey-López JP, Díaz LE, et al. Active Commuting to School and Cognitive Performance in Adolescents. The AVENA Study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.244.

Larouche R, Saunders TJ, Faulkner GEJ, Colley R, Tremblay M. Associations between active school transport and physical activity, body composition, and cardiovascular fitness: a systematic review of 68 studies. J Phys Act Health. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.2011-0345.

Smith L, Norgate SH, Cherrett T, Davies N, Winstanley C, Harding M. Walking school buses as a form of active transportation for children – a review of the evidence. J Sch Health. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12239.

Thaller M, Schnabel F, Gollner E. Schoolwalker – eine Initiative zur gesundheits- und umweltbewussten Mobilität bei Kindern. Präv Gesundheitsf. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11553-013-0425-y.

Jones RA, Blackburn NE, Woods C, Byrne M, van Nassau F, Tully MA. Interventions promoting active transport to school in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev Med. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.03.030.

Nelson NM, Foley E, O'Gorman DJ, Moyna NM, Woods CB. Active commuting to school: how far is too far? Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2008. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-5-1.

Belter T, von Harten M, Sorof S. Working paper about costs and benefits of cycling. n.d. http://enercitee.eu/files/dokumente/Subprojects/SUSTRAMM/SustraMM_Costs_and_benefits_of_cycling.pdf. Accessed 10 Nov 2019.

Bundesministerium für Verkehr und digitale Infrastruktur (bmvi). Radverkehr in Deutschland – Zahlen, Daten, Fakten. Berlin: AZ Druck und Datentechnik; 2014.

Schöb A. Fahrradnutzung bei Stuttgarter Schülern. Erste Ergebnisse einer Schülerinnen- und Schülerbefragung an Stuttgarter Schulen 2005. Stat Inf. 2006;11:294–317.

Reimers AK, Jekauc D, Peterhans E, Wagner MO, Woll A. Prevalence and socio-demographic correlates of active commuting to school in a nationwide representative sample of German adolescents. Prev Med. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.11.011.

Pavelka J, Sigmundová D, Hamřík Z, Kalman M, Sigmund E, Mathisen F. Trends in active commuting to school among Czech schoolchildren from 2006 to 2014. Cent Eur J Public Health. 2017. https://doi.org/10.21101/cejph.a5095.

Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans Midcourse Report Subcommittee of the President’s Council on Fitness, Sports & Nutrition. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans Midcourse Report. Strategies to Increase Physical Activity Among Youth. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2012.

Schönbach DMI, Altenburg TM, Chinapaw MJM, Marques A, Demetriou Y. Strategies and effects of promising school-based interventions to promote active school transportation by bicycle among children and adolescents: protocol for a systematic review. Syst Rev. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-019-1216-0.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. The PRISMA Group Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed1000097.

Murdoch University: Systematic Reviews - Research Guide. Using PICO or PICo (2019). https://libguides.murdoch.edu.au/systematic/PICO. Accessed 10 Nov 2019.

Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, Abraham C, Francis J, Hardeman W, et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-013-9486-6.

Kornet-van der Aa DA, Altenburg TM, van Randeraard-van der Zee CH, Chinapaw MJM. The effectiveness and promising strategies of obesity prevention and treatment programmes among adolescents from disadvantaged backgrounds: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2017; doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12519.

Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP). Quality Assessment Tool For Quantitative Studies. 1998. https://merst.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/quality-assessment-tool_2010.pdf. Accessed 03 Apr 2019.

Pont K, Ziviani J, Wadley D, Abbott R. The model of Children's active travel (M-CAT): a conceptual framework for examining factors influencing children's active travel. Aust Occup Ther J. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1630.2010.00865.x.

Wong BY-M, Faulkner G, Buliung R, Irving H. Mode shifting in school travel mode: examining the prevalence and correlates of active school transport in Ontario, Canada. BMC Public Health. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-618.

Ginja S, Arnott B, Araujo-Soares V, Namdeo A, McColl E. Feasibility of an incentive scheme to promote active travel to school: a pilot cluster ranomised trial. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40814-017-0197-9.

Hinckson EA, Badland HM. School travel plans: preliminary evidence for changing school-related travel patterns in elementary school children. Am J Health Promot. 2011. https://doi.org/10.4278/ajhp.090706-ARB-217.

Børrestad LAB, Østergaard L, Andersen LB, Bere E. Experiences from a randomised, controlled trial on cycling to school: does cycling increase cardiorespiratory fitness? Scand J Public Health. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494812443606.

Østergaard L, Støckel JT, Andersen LB. Effectiveness and implementation of interventions to increase commuter cycling to school: a quasi-experimental study. BMC Public Health. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-2536-1.

Christiansen LB, Toftager M, Ersbøll AK, Troelsen J. Effects of a Danish multicomponent physical activity intervention on active school transport. J Transp Health. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jth.2014.05.002.

Ducheyne F, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Lenoir M, Cardon G. Effects of a cycle training course on children's cycling skills and levels of cycling to school. Accid Anal Prev. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2014.01.023.

Gutierrez CM, Slagle D, Figueras K, Anon A, Huggins AC, Hotz G. Crossing guard presence: impact on active transportation and injury prevention. J Transp Health. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jth.2014.01.005.

Huang C, Dannenberg AL, Haaland W, Mendoza JA. Changes in self-efficacy and outcome expectations from child participation in bicycle Trains for Commuting to and from school. Health Educ Behav. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198118769346.

Mendoza JA, Haaland W, Jacobs M, Abbey-Lambertz M, Miller J, Salls D, et al. Bicycle trains, cycling and physical activity: a pilot cluster RCT. Am J Prev Med. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2017.05.001.

Villa-González E, Ruiz JR, Ward DS, Chillón P. Effectiveness of an active commuting school-based intervention at 6-month follow-up. Eur J Pub Health. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckv208.

Villa-González E, Ruiz JR, Mendoza JA, Chillón P. Effects of a school-based intervention on active commuting to school and health-related fitness. BMC Public Health. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3934-8.

Cavill N, Davis A. Active travel & physical activity evidence review. 2019. https://www.sportengland.org/media/13943/active-travel-full-report-evidence-review.pdf. Accessed 10 Nov 2019.

Coya. Global Bicycle Cities Index 2019. n.d. https://www.coya.com/bike/index-2019. Accessed 13 Aug 2020.

Cardon GM, Van Acker R, Seghers J, De Martelaer K, Haerens LL, De Bourdeaudhuij IMM. Physical activity promotion in schools: which strategies do schools (not) implement and which socioecological factors are associated with implementation? Health Educ Res. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cys043.

Blümle A, Meerpohl JJ, Wolff R, Antes G. Evidenzbasierte Medizin und systematische Übersichtsarbeiten. Die Rolle der Cochrane Collaboration MKG-Chirurg. 2009. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12285-009-0081-6.

Yang Y, Diez-Roux AV. Using an agent-based model to simulate children's active travel to school. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-10-67.

Coombes E, Jones A. Gamification of active travel to school: a pilot evaluation of the beat the street physical activity intervention. Health Place. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2016.03.001.

Boarnet MG, Day K, Anderson C, McMillan T, Alfonzo M. California's Safe Routes to School Program. Impacts on Walking, Bicycling and Pedestrian Safety. J Am Plan Assoc. 2005. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944360508976700.

Di Pietro G, Hughes I. TravelSMART schools: there really is a better way to go! In: Marchettini N, Brebbia CA, Tiezzi E, Wadhwa LC, editors. The Sustainable City III. Ashurst: WIT Press; 2004. p. 653–62.

Larouche R, Ghekiere A. An ecological model of active transportation. In: Larouche R, editor. Children’s active transportation. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2018. p. 93–103.

Ahlport KN, Linnan L, Vaughn A, Evenson KR, Ward DS. Barriers to and facilitators of walking and bicycling to school: formative results from the non-motorized travel study. Health Educ Behav. 2008. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198106288794.

Bartholomew Eldredge LK, Markham CM, Ruiter RAC, Fernández ME, Kok G, Parcel GS. Planning health promotion programs. An intervention mapping approach. 4th ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2016.

Acknowledgements

We thank Hedwig Bäcker and Christian Pauls, University Library – Technical University of Munich, who helped to finalize the search strategy for this systematic review. Furthermore, the authors are thankful for the support of the ACTS-Consortium.

Funding

This systematic review was supported by a grant (2018–3291/001–001) from the Education, Audiovisual and Culture Executive Agency (EACEA) ERASMUS+ Sport Program. Moreover, this work was supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG) and the Technical University of Munich within the funding program Open Access Publishing. The funders had no role in preparing and conducting this systematic review, in interpreting and deciding to publish the results, or in drafting this manuscript. Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DS pretested, conducted and updated the literature search, was the first reviewer, conceptualized the data extraction sheet, extracted all data, evaluated intervention strategies, rated the methodological quality of each study, analyzed data, and drafted the manuscript. YD and DS contributed equally to developing the search strategy and the concept of the systematic review. In addition, both worked on designing the inclusion checklist. Moreover, YD was the third evaluator of the methodological quality assessment. TA was the second reviewer in 2018, involved in data extraction, evaluation of intervention strategies, and rating of the studies’ methodological quality as evaluator. AM helped to update the literature search as the second reviewer in 2019, performed data extraction as well as the methodological quality assessment of studies as evaluator. MCAP proposed the methods of the systematic review, in particular the methodological quality assessment, advised DS on handling study data and critically revised the manuscript to obtain final decisions. YD, TA, AM and MCAP provided comments as well as edits to the manuscript. The final manuscript was approved by all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement.

Additional file 2.

Search formula used in the eight electronic databases.

Additional file 3.

Sections, components and items of the quality assessment tool.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Schönbach, D.M.I., Altenburg, T.M., Marques, A. et al. Strategies and effects of school-based interventions to promote active school transportation by bicycle among children and adolescents: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 17, 138 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-020-01035-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-020-01035-1