Abstract

Background

Despite increasing numbers of cancer survivors and evidence that diet and physical activity improves the health of cancer survivors, most do not meet guidelines. Some social cognitive theory (SCT)-based interventions have increased physical activity behavior, however few have used objective physical activity measures. The Exercise and Nutrition Routine Improving Cancer Health (ENRICH) randomized controlled trial reported a significant intervention effect for the primary outcome of pedometer-assessed step counts at post-test (8-weeks) and follow-up (20-weeks). The aim of this study was to test whether the SCT constructs operationalized in the ENRICH intervention were mediators of physical activity behavior change.

Methods

Randomized controlled trial with 174 cancer survivors and carers assessed at baseline, post-test (8-weeks), and follow-up (20-weeks). Participants were randomized to the ENRICH six session face-to-face healthy lifestyle program, or to a wait-list control. Hypothesized SCT mediators of physical activity behavior change (self-efficacy, behavioral goal, outcome expectations, impediments, and social expectations) were assessed using valid and reliable scales. Mediation was assessed using the Preacher and Hayes SPSS INDIRECT macro.

Results

At eight weeks, there was a significant intervention effect on behavioral goal (A = 9.12, p = 0.031) and outcome expectations (A = 0.25, p = 0.042). At 20 weeks, the intervention had a significant effect on self-efficacy (A = 0.31, p = 0.049) and behavioral goal (A = 13.15, p = 0.011). Only changes in social support were significantly associated with changes in step counts at eight weeks (B = 633.81, p = 0.023). Behavioral goal was the only SCT construct that had a significant mediating effect on step counts, and explained 22 % of the intervention effect at 20 weeks (AB = 397.9, 95 % CI 81.5–1025.5).

Conclusions

SCT constructs had limited impact on objectively-assessed step counts in a multiple health behavior change intervention for cancer survivors and their carers. Behavioral goal measured post-intervention was a significant mediator of pedometer-assessed step counts at 3-months after intervention completion, and explained 22 % of the intervention effect. Future research should examine the separate impact of goals and planning, as well as examining mediators of behavior maintenance in physical activity interventions targeting cancer survivors.

Trial registration

Australian and New Zealand Clinical Trials registry ANZCTRN1260901086257.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The number of cancer survivors is increasing due to the aging population and improvements in early detection and cancer treatments [1]. There are an estimated 28 million people worldwide living with cancer who were diagnosed in the previous five years [2]. Cancer survivors are at-risk of secondary cancers, other co-morbidities (like diabetes and cardiovascular disease), and poor physical and psychosocial health [3]. Current guidelines for cancer survivors report that physical activity (PA) can be safely performed both during and after cancer treatment [4–6], and PA has been shown to improve survival, risk of recurrence and side-effects from cancer and its treatments [7–13]. Despite these benefits, it is estimated that only 28 to 47 % of cancer survivors meet PA guidelines [14–16]. To date, there have been a number of trials investigating the efficacy of PA in clinical settings. However, there have been fewer trials investigating how to promote long-term behavior change in cancer survivors. Most PA trials have targeted breast cancer survivors and have focussed on short-term outcomes (12 weeks) [17–19]. Few PA trials have used an objective PA measure, or assessed the impact of behavior change after the intervention [17–19]. Carers of cancer survivors share many of the same behavioral risk factors as survivors [20, 21], and also experience poor physical and psychosocial health [22], however they are rarely targeted in interventions.

Interventions that are based on theory have shown promise in promoting positive behavior change [23–25]. Theory-based interventions allow for an exploration of why an intervention worked, and what strategies were crucial to their success [26–28]. While many interventions claim to be theory-based, often their theoretical constructs are inadequately described, and the constructs rarely tested [25, 29–31]. Mediation analysis can be used to identify the most effective components of an intervention and help to explore the mechanisms of behavior change. A previous review of PA interventions in adult non-clinical populations reported that only half of reviewed studies showed evidence that the intervention changed PA and the proposed mediator of behavior change, and the outcomes of mediation were mixed [32]. Identifying the mechanisms of behavior change is important in refining existing theories, and developing new theories of behavior change.

Social cognitive theory (SCT) offers principles on how to predict and change health behavior [33]. Knowledge of health risks and benefits precede all the SCT constructs, with self-efficacy affecting behavior directly, and indirectly by the impact on goals, outcome expectations, and perceived facilitators and impediments [33]. The category of ‘goals’ is broad, and for the purpose of this paper, the term goal or behavioral goal may be defined as “detailed planning of what the person will do, including definition of the behavior specifying frequency, intensity or duration” [26], and includes both proximal and distal goals [34]. The outcome expectations are the perceived positive and negative effects of the behavior, which are directly influenced by self-efficacy [33, 35]. Self-efficacy includes confidence to overcome barriers to successful behavior change, as well as the ability to perform and assess behavior under a range of personal, social, and environmental conditions [33]. In a systematic review and meta-analysis (n = 12 trials) of SCT-based interventions for cancer survivors, SCT-based interventions were found to be effective at changing PA behavior with an effect size of 0.33 [25]. However, the studies were heterogeneous and there were no specific SCT constructs, or specific intervention delivery modes that were related to intervention efficacy, and results did not differ if the intervention targeted single or multiple health behavior interventions [25].

The Exercise and Nutrition Routine Improving Cancer Health (ENRICH) trial is a theoretically-based multiple health behavior change intervention for cancer survivors and carers. ENRICH was evaluated using a randomized controlled trial and reported significant intervention effects on mean daily step counts (as measured by 7 days of pedometry) at both 8- and 20-week follow-up [36]. The intervention, based on SCT [33] and a chronic disease self-management model [37], consisted of healthy eating knowledge and skill development, resistance training principles and exercises utilizing a Gymstick™ and a home-based walking program using a pedometer. The aim of the current study was to investigate whether the SCT constructs targeted in the intervention served as mediators of the intervention effect on pedometer-assessed step counts at 8- and 20-weeks.

Methods

Study design

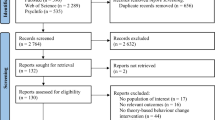

The methods and primary analysis have been described in detail elsewhere [36, 38]. In brief, people with a previous diagnosis of cancer and their carers were recruited from health professionals, cancer support groups, media, and support services of a cancer charity in Sydney, Australia, during 2010 to 2012. The reporting of the trial conformed to the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines for pragmatic RCTs [39]. The trial was registered with the Australian and New Zealand Clinical Trials registry (ANZCTRN1260901086257), and ethics approval was obtained from the University of Newcastle Human Research Ethics Committee (H-2009-0347).

Sample

Included participants were: 1) individual diagnosed with cancer who had completed all active cancer treatment (“cancer survivor”), or carer of cancer survivor; 2) no food or dietary restrictions as a result of surgery or treatment; 3) aged 18 years or older; 4) fluent in English; 5) signed medical clearance from their General Practitioner; and 6) with a functional performance score of two or less on the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group criteria (that is “at least ambulatory and capable of all self-care…or up and about more than 50 % of waking hours”) [40]. Participants provided informed consent.

Intervention

The ENRICH program involved six face-to-face group education and skill development sessions held over 8 weeks. Participants were provided with a workbook (which contained program notes, activities, and handouts), an open pedometer and a Gymstick™ (a lightweight graphite shaft, with elastic tubing and foot straps that provide resistance to exercise all major muscle groups) [41]. Each group-based session delivered simultaneous multiple health behavior content covering a home-based walking program (using a pedometer), home-based resistance training program (using a Gymstick™), and information about healthy eating (the Australian Guide to Healthy Eating, fruit and vegetables, maintaining a healthy weight, fats, meat, salt, dietary supplements, alcohol, and reading food labels). Sessions included a mix of didactic information delivery and practical activities. Each session was co-facilitated by a qualified exercise specialist (Accredited Exercise Physiologist or Physiotherapist) and an Accredited Practising Dietician. The content and delivery of sessions was operationalized using the principles of SCT [33] and a chronic disease self-management framework [37]. The specific theoretical constructs that were operationalized included knowledge, behavioral goals, self-efficacy, outcome expectations, impediments, and social support (see Table 1). Whilst ENRICH was a multiple health behavior change intervention targeting both PA (aerobic and resistance) and healthy eating, the focus of this paper is on the primary outcome of pedometer-assessed step counts. Mediators of dietary change were not assessed, due to the complexity and number of individual dietary behaviors that were targeted in the intervention (fruit, vegetables, fat, salt, meat consumption, energy, alcohol), and the lack of brief, validated measures. The specific intervention strategies, how they relate to each theoretical construct, and the specific behavior change techniques from the CALO-RE taxonomy [42] are detailed in Table 1.

Control: After completing 20-week study measures, control group participants (n = 58) attended the ENRICH program.

Assessments

Data were collected by written survey, wearing a sealed pedometer, and completing a concurrent log sheet, at baseline, eight weeks (intervention completion), and 20-weeks (3 months post-intervention, 5 months post-randomization).

The primary outcome was step counts, as measured by sealed pedometer (Yamax SW200) for seven days. Participants recorded time worn, and occasions of other activities (resistance training, swimming, water aerobics, cycling) not captured by pedometry. These activities were converted to sex-specific step counts using previously reported values [43] and were added to the total step count value.

A description and psychometric properties of each of the hypothesized mediators assessed by written survey is reported in Table 1. The hypothesized mediators included behavioral goal, self-efficacy, outcome expectations, impediments, and social support. An eight week time reference, and definition of ‘regular PA’ was provided for the hypothesized mediators. Consistent with PA guidelines, ‘regular physical activity’ was defined as “achieving at least 30 minutes of moderate or vigorous-intensity activity on most, preferably all, days of the week” [44].

Statistical analyses

Analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21 (IBM Corp, Armonk, New York, USA). Relevant items were reverse-coded, and a mean score for each construct was computed. Cronbach alphas for each construct, except for behavioral goal, are reported in Table 1. Mediation analyses were conducted using the INDIRECT macro developed by Preacher and Hayes [45]. The macro computes the following steps simultaneously: i) regression coefficients for the impact of the intervention on the potential mediators (pathway A or action theory); ii) the associations between changes in mediators and changes in pedometer-assessed step counts, independent of study group allocation (pathway B or conceptual theory); iii) the total effects (pathway C), direct effects (pathway C’), and indirect (pathway AB) intervention effects. The mediation pathways are illustrated in Fig. 1. Bias-corrected bootstrapped 95% asymmetrical confidence intervals were computed for the indirect effect [45]. Significant mediation was established if the confidence intervals did not include zero. The proportion of the intervention effect that was attributed to each mediator was computed by dividing the indirect effect (pathway AB) by the total effect (pathway C’ + pathway AB). Single mediator models were computed for pedometer-assessed step counts at 8- and 20-weeks, adjusting for baseline step count and mediator variables. Multiple mediator models were computed for step counts at 20-weeks, adjusted for baseline step count and mediator variables.

Mean scores of each SCT construct at eight weeks were used in all analyses. Mediation analysis was undertaken using a completers-only analysis, with sensitivity analysis to examine the impact of missing data. The estimation maximization algorithm in SPSS was used to impute missing outcome and mediator data. Pedometer-assessed data and Active Australia survey data were used to predict missing outcome data (pedometer-assessed step counts).

The result of Little’s Missing Completely At Random (MCAR) test confirmed that outcome data were missing completely at random (Chi-Square = 280.9, df = 282; p = 0.51). Missing mediator values were imputed for each individual item and the results of Little’s Missing Completely at Random (MCAR) test confirmed that mediator data were also missing completely at random. Results of the intention-to-treat mediation analysis were then compared to the completers-only analysis. Demographics of participants who completed the study (defined as not withdrawn at 20-weeks) were compared to those who dropped out of the study.

Results

Participants (n = 174) were randomized and 133 completed baseline data collection [36]. At 8-week data collection, 82 % (n = 109) of the sample were retained, and at 20-weeks, 71 % (n = 94) of the sample were retained. The majority of participants who withdrew, did so prior to attending any ENRICH sessions (n = 51). Study groups had similar baseline demographic characteristics (see Table 2). Three-quarters of the sample were female, with mean age of 57 years, and were cancer survivors. The majority of cancer survivors were diagnosed with breast cancer, and had been diagnosed three to four years previously. There were 24 carers in the sample and 12 participants who were both cancer survivors and carers.

A comparison of participants who dropped out, and those who completed the study is reported in Table 3. Compared to those who completed the study, people who dropped out of the study were significantly more likely to be in the intervention group (73 % vs 49 %; p = 0.009), and to report being diagnosed with arthritis (54 % vs 32 %; p = 0.028). Participants who dropped out of the study were also more likely to report co-morbidities (88 % vs 74 %), mental health problems (44 % vs 28 %), to report longer time since diagnosis (4.2 years vs 3.2 years), and were more likely to have received chemotherapy (83 % vs 71 %), however these differences did not reach statistical significance. However, there were no differences in the mediation results between the completers analysis and the intention-to-treat analysis. Therefore, the results of the completers analysis was reported as the primary mediation analysis with the intention-to-treat reported as a sensitivity analysis.

Intervention effects

Overall intervention effects have been reported elsewhere [36]. In summary, significant group-by-time effects were found for mean daily steps at 8-weeks (adjusted mean difference 2810 steps/day; 95 % CI 1238–4382) and at 20-weeks (adjusted mean difference 2782 steps/day, 95 % CI 818–4745) (P = 0.0009) (see Table 4). Mean values for mediators at all three time-points are also reported in Table 4.

Mediation effects

The results of the mediation analysis are reported in Table 5.

Action theory test

After controlling for baseline values, there were significant intervention effects for behavioral goal (A = 9.12, p = 0.031) and outcome expectations (A = 0.25, p = 0.042) at post-test (8-weeks). At 20-weeks, there were significant intervention effects for self-efficacy (A = 0.31, p = 0.049) and behavioral goal (A = 13.15, p = 0.011).

Conceptual theory test

At 8-weeks, changes in social support were significantly associated with changes in pedometer-assessed step counts (B = 633.81, p = 0.023). At 20-weeks, there were no significant relationships between changes in any SCT constructs and pedometer-assessed step counts.

Significance of mediated effect

Changes in behavioral goal satisfied the criteria for mediation and explained 22 % of the intervention effect on pedometer-assessed step counts at 20-weeks (AB = 397.88, 95 % CI 81.5–1025.5). No other constructs had a significant mediation effect at eight or 20-weeks.

In a multiple mediator model that examined intervention effects at 20-weeks, the individual construct behavioral goal had a significant mediating effect on step counts (AB = 464.74, 95 % CI 25.9–1548.87), and in the model containing all of the SCT constructs, this model explained 7 % of the intervention effect.

Sensitivity analysis using the estimation maximization algorithm was undertaken to assess the impact of missing data from those who did not complete the trial. There was no change in the main findings: behavioral goal remained a significant construct at 8- and 20-weeks, and explained 10 % of the intervention effect on step counts (AB = 186.2; 95 % CI 13.6–606.9).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to identify if constructs from SCT mediated changes in pedometer-assessed step counts in the ENRICH intervention for cancer survivors and carers. This study demonstrated that behavioral goal mediated the effect of the ENRICH intervention on step counts at 20-week follow-up, and accounted for 22 % of the intervention effect on step counts. No other constructs satisfied the criteria for mediation.

At post-test, the intervention was found to have a significant impact on behavioral goal and outcome expectations. There were no intervention effects for self-efficacy, impediments, or social support. At follow-up, the ENRICH intervention significantly improved self-efficacy and behavioral goal. However, behavioral goal was shown to have a significant mediating effect on pedometer-assessed step counts in both multiple and single mediator models, and explained between 7–22 % of the intervention effect. During the initial ENRICH session, participants set a goal to walk every day (at whatever time and distance was appropriate to their capability), and during subsequent sessions participants set step goals, monitored their steps using a pedometer and diary, reviewed and revised their goal each week. They were encouraged to write down SMART goals (specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, and with time-frames). Ninety-five percent of participants reported that ENRICH helped them to set reasonable goals that were within reach. This highlights the important role of goal setting and intentions in increasing PA behavior. Goal setting is a key element to many other behavior change theories, such as the Reasoned Action Approach [46] or Health Action Process Approach [47]. It may be that SCT is not the most appropriate behavior change theory for this target group and future research should examine the utility of other behavior change theories that hold goal setting as a central component. A meta-analysis of behavior change interventions has concluded that a medium-to-large change in intention leads to a small-to-medium change in behavior [48, 49]. Goals and intentions have been identified as a crucial part of behavior change and identified as a key part of theoretical frameworks, however there remains a gap between goal formation and behavior change. Recent literature has posited that planning is an important mediator between intentions and behavior [50, 51], and may help overcome the intention-behavior gap. The ENRICH trial did not assess the impact of goals and action planning separately, and future trials could incorporate goals and planning as distinct constructs, and test the causal pathway between goals, planning and behavior.

A review by Rhodes and colleagues examined the mediators of behavior change between selected SCT constructs and PA change and reported mixed results [32]. They also reported that, of the three trials that tested SCT constructs, none assessed or reported a conceptual theory link [32]; this is similar to the findings in this current analysis. However, in contrast to our results, other interventions based on SCT have reported that self-efficacy was the most commonly reported construct that influenced the results of the intervention [10, 52, 53]. Four studies reported improvements in self-efficacy were associated with increased PA [52–55]. However, mediation analyses in two trials identified that theoretical constructs only partially mediated intervention effects [56–58]. One SCT-based trial reported increased social support resulting from the intervention mediated the treatment effects on participants’ activity levels [54]. Similar to other studies, we found that outcome expectations and impediments were not mediators of PA [32, 54]. Ashford and colleagues reviewed 27 trials and found that half of the studies had included identification of PA barriers, and that this construct was significantly associated with lower self-efficacy [59]. There is limited support for SCT constructs as mediators of PA behavior change in this study and in other similar trials.

Response shift theory has been offered as an explanation for null findings in previous PA interventions targeting clinical populations [60, 61]. SCT posits that self-efficacy has direct influence on goals, outcome expectations, and impediments, as well as behavior [33]. Despite self-efficacy not being a significant mediator of change in this analysis, it may still have exerted important effects on other constructs, which are not accounted for in this analysis. Trials have supported links between self-regulatory efficacy and intentions [62]; self-efficacy and planning [50]; and intentions and barriers [48]. Behavior change techniques that prompt self-monitoring of behavioral outcomes and plan social support/social change have been associated with higher self-efficacy, and higher effect size for PA behavior change [63]. Measurement and analysis of the specific behavior change techniques was not undertaken in this study. Similar to other trials that used objective PA measures [54, 61, 64], changes in the SCT constructs explained a small amount of variance in PA. Alternatively, trials that have assessed PA by self-report have found that SCT constructs explain a greater amount of variance [65]. This is known as common method variance, and refers to the “variance that is attributable to the measurement method rather than to the constructs the measures are assumed to represent” [66]. Due to these differences, it is important to use objective measures of PA. As this was a highly motivated sample, it would be interesting to assess other constructs which may have been important, such as motivation, habit, or PA planning [32, 67, 68]. It could be that the constructs are different, depending on whether participants are trying to increase PA or maintain PA [67].

There were few differences between mediation analysis using the completers-only data or the intention-to-treat data. Using data from both eight and 20 weeks, the only construct shown to have a significant mediating relationship was behavioral goal which mediated the effect between the intervention and PA behavior change at 20 weeks, indicating that the completers-only analysis results are robust, despite the withdrawal rate.

Limitations of this study

There was little change in the PA mediators as a result of the intervention, which raises several issues. The mediators were assessed in relation to “regular PA”, however the ENRICH intervention specifically targeted walking and resistance training. The lack of specificity may have also been an issue in how SCT constructs were defined. Self-efficacy was examined as one category, rather than breaking it down into the more specific constructs of task or barrier self-efficacy. There may have been cross-over or contamination between the individual construct measures, and it may be difficult to separate the individual effects of self-efficacy and outcome expectations [69]. The measure used to assess goal setting in this analysis is a measure of likelihood of performing regular PA, which may be a measure of motivation or intention, and makes it difficult to tease out separate effects of these constructs.

In addition, the mediator questions may not have been sensitive enough to detect change over eight weeks, particularly as baseline values were relatively high. It is not surprising that baseline values were high, as participants for this trial self-selected and were likely to be highly motivated to want to change PA and diet behaviors. Mediators of dietary change were not assessed, due to the complexity and number of individual dietary behaviors that were targeted in the intervention (fruit, vegetables, fat, salt, meat consumption, energy, alcohol), and the lack of brief, validated measures.

Strengths of this study

The PA intervention was developed using SCT, with all PA constructs operationalized, and tested for their mediating effect. The rigorous application and testing of theoretical constructs is essential in moving theory forward and understanding the components crucial to intervention success. It is important to test for mediators in successful interventions to find out why they worked [70]. The ENRICH trial is a novel intervention that targeted survivors and carers of multiple cancer types, and focused on multiple lifestyle behaviors (PA/walking, resistance training, sitting, and a range of dietary behaviors). The inclusion of both cancer survivors and carers was expected to enhance social support. The lack of improvement in social support may have been due to the small number of carers who participated, or it could be that this strategy was not sufficient to improve participants’ perceived levels of social support. The success of the ENRICH intervention may be due to additional theoretical constructs (such as stage of change) or it may be related to specific behavior change techniques such as self-regulatory behaviors.

Future research

Future studies should use a taxonomy of behavior change techniques to develop the ‘active ingredients’ of an intervention [71, 72]. Theoretical constructs have so far, shown mixed results in mediation analyses. There is some consistent evidence for specific behavior change constructs (eg self-regulatory behaviors) [54, 73, 74], and these specific behavior change constructs offer a promising way to develop potential future models of behavior change that should be tested in RCTs. Measures may need to be developed or refined to evaluate the change in these constructs. Use of an objective measure of behavior change outcome should be used in trials with PA or weight as an outcome. Maintenance of behavior change is an area that requires further intervention. We know little about how to support cancer survivors and carers to sustain positive behavior change. Identifying differences in mediators of behavior change and maintenance are important areas for future research.

Conclusions

Behavioral goal was the only SCT construct to mediate the intervention effect on pedometer-assessed step counts at 20 week follow-up and accounted for 22 % of the intervention effect. The utility of behavioral goal for promoting PA was supported, however there was little evidence to support self-efficacy, outcome expectations, impediments, or social support for mediating the effect of PA behavior change. Future research should consider using the taxonomy of behavior change techniques to develop and evaluate interventions. It appears that the use of specific theoretical constructs and behavior change techniques offer the most promise for identifying the techniques critical to behavior change success.

Abbreviations

- BCT:

-

behavior change technique

- ENRICH:

-

Exercise and Nutrition Routine Improving Cancer Health

- PA:

-

physical activity

- RCT:

-

randomized controlled trial

- SCT:

-

social cognitive theory

References

de Moor JS, Mariotto AB, Parry C, Alfano CM, Padgett L, Kent EE, et al. Cancer survivors in the United States: prevalence across the survivorship trajectory and implications for care. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22:561–70.

Bray F, Ren J-S, Masuyer E, Ferlay J. Global cancer transitions according to the Human Development Index (2008–2030): a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:790–801.

Petrick JL, Foraker RE, Kucharska-Newton AM, Reeve BB, Platz EA, Stearns SC, et al. Trajectory of overall health from self-report and factors contributing to heath declines among cancer survivors. Cancer Causes Control. 2014;25:1179–86.

Campbell A, Stevinson C, Crank H. The BASES expert statement on exercise and cancer survivorship. J Sports Sci. 2012;30:949–52.

Hayes SC, Spence RR, Galvão DA, Newton RU. Australian Association for Exercise and Sport Science position stand: Optimising cancer outcomes through exercise. J Sci Med Sport. 2009;12:428–34.

Schmitz KH, Courneya KS, Matthews C, Demark-Wahnefried W, Galvao DA, Pinto BM, et al. American College of Sports Medicine roundtable on exercise guidelines for cancer survivors. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42:1409–26.

Ballard-Barbash R, Friedenreich CM, Courneya KS, Siddiqi SM, McTiernan A, Alfano CM. Physical activity, biomarkers, and disease outcomes in cancer survivors: a systematic review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104:1–26.

Focht BC, Clinton SK, Devor ST, Garver MJ, Lucas AR, Thomas-Ahner JM, et al. Resistance exercise interventions during and following cancer treatment: a systematic review. J Support Oncol. 2013;11:45–60.

Fong DYT, Ho JWC, Hui BPH, Lee AM, Macfarlane DJ, Leung SSK, et al. Physical activity for cancer survivors: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMJ. 2012;344:e70.

Ligibel J. Lifestyle factors in cancer survivorship. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3697–704.

Pekmezi DW, Demark-Wahnefried W. Updated evidence in support of diet and exercise interventions in cancer survivors. Acta Oncol. 2011;50:167–78.

Sabiston CM, Brunet J. Reviewing the benefits of physical activity during cancer survivorship. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2011;6:167–77.

Speck RR, Courneya KS, Masse LC, Duval S, Schmitz KH. An update of controlled physical activity trials in cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cancer Surviv. 2010;4:87–100.

Blanchard CM, Courneya KS, Stein K. Cancer survivors’ adherence to lifestyle behavior recommendations and associations with health-related quality of life: results from the American Cancer Society’s SCS-II. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2198–204.

Berry NM, Miller MD, Woodman RJ, Coveney J, Dollman J, Mackenzie CR, et al. Differences in chronic conditions and lifestyle behaviour between people with a history of cancer and matched controls. Med J Aust. 2014;201:96–100.

Eakin EG, Youlden DR, Baade PD, Lawler SP, Reeves MM, Heyworth JS, et al. Health behaviors of cancer survivors: data from an Australian population-based survey. Cancer Causes Control. 2007;18:881–94.

Kampshoff CS, Jansen F, van Mechelen W, May AM, Brug J, Chinapaw MJM, et al. Determinants of exercise adherence and maintenance among cancer survivors: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2014;11:80.

Short CE, James EL, Stacey F, Plotnikoff RC. A qualitative synthesis of trials promoting physical activity behaviour change among post-treatment breast cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7:570–81.

Spark LC, Reeves MM, Fjeldsoe BS, Eakin EG. Physical activity and/or dietary interventions in breast cancer survivors: a systematic review of the maintenance of outcomes. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;77:74–82.

Beesley VL, Price MA, Webb PM. Loss of lifestyle: health behavior and weight changes after becoming a caregiver of a family member diagnosed with ovarian cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2010;19:1949–56.

Kotronoulas G, Wengstrom Y, Kearney N. Informal carers: a focus on the real caregivers of people with cancer. Forum of Clinical Oncology. 2012;3:58–65.

Northouse L, Williams A-L, Given B, McCorkle R. Psychosocial care for family caregivers of patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1227–34.

Glanz K, Bishop DB. The role of behavioral science theory in development and implementation of public health interventions. Annu Rev Public Health. 2010;31:399–418.

Noar SM, Benac CN, Harris MS. Does tailoring matter? Meta-analytic review of tailored print health behavior change interventions. Psychol Bull. 2007;133:673–93.

Stacey FG, James EL, Chapman K, Courneya KS, Lubans DR. A systematic review and meta-analysis of social cognitive theory-based physical activity and/or nutrition behavior change interventions for cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2015;9:305–38.

Abraham C, Michie S. A taxonomy of behavior change techniques used in interventions. Health Psychol. 2008;27:379–87.

Lubans DR, Foster C, Biddle SJH. A review of mediators of behavior in interventions to promote physical activity among children and adolescents. Prev Med. 2008;47:463–70.

Nigg CR, Allegrante JP, Ory M. Theory-comparison and multiple-behavior research: common themes advancing health behavior research. Health Educ Res. 2002;17:670–9.

Avery KNL, Donovan JL, Horwood J, Lane JA. Behavior theory for dietary interventions for cancer prevention: a systematic review of utilization and effectiveness in creating behavior change. Cancer Causes Control. 2013;24:409–20.

Hutchison AJ, Breckon JD, Johnston LH. Physical activity behavior change interventions based on the Transtheoretical Model: a systematic review. Health Educ Behav. 2008;36:829–45.

Painter JE, Borba CPC, Hynes M, Mays D, Glanz K. The use of theory in health behavior research from 2000 to 2005: a systematic review. Ann Behav Med. 2008;35:358–62.

Rhodes RE, Pfaeffli LA. Mediators of physical activity behavior change among adult non-clinical populations: a review update. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2010;7:37.

Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31:143–64.

Bandura A. Health promotion from the perspective of social cognitive theory. Psychol Health. 1998;13:623–49.

Bandura A. Human agency in social cognitive theory. Am Psychol. 1989;44:1175–84.

James EL, Stacey FG, Chapman K, Boyes AW, Burrows T, Girgis A, et al. Impact of a nutrition and physical activity intervention (ENRICH: Exercise and Nutrition Routine Improving Cancer Health) on health behaviors of cancer survivors and carers: a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:710.

Lorig K. Chronic disease self-management. Am Behav Sci. 1996;39:676–83.

James EL, Stacey F, Chapman K, Lubans DR, Asprey G, Sundquist K, et al. Exercise and nutrition routine improving cancer health (ENRICH): The protocol for a randomized efficacy trial of a nutrition and physical activity program for adult cancer survivors and carers. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:236.

Zwarenstein M, Treweek S, Gagnier JJ, Altman DG, Tunis S, Haynes B, et al. Improving the reporting of pragmatic trials: an extension of the CONSORT statement. BMJ. 2008;337:a2390.

Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, Horton J, Davis TE, McFadden ET, et al. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol. 1982;5:649–55.

Lubans DR, Mundey CM, Lubans NJ, Lonsdale CC. Pilot randomized controlled trial: elastic-resistance-training and lifestyle-activity intervention for sedentary older adults. J Aging Phys Act. 2013;21:20–32.

Michie S, Ashford S, Sniehotta FF, Dombrowski SU, Bishop A, French DP. A refined taxonomy of behavior change techniques to help people change their physical activity and healthy eating behaviors: The CALO-RE taxonomy. Psychol Health. 2011;26:1479–98.

Miller R, Brown W, Tudor-Locke C. But what about swimming and cycling? How to “count” non-ambulatory actvity when using pedometers to assess physical activity. J Phys Act Health. 2006;3:257–66.

Australia’s Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior Guidelines. http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/content/health-pubhlth-strateg-phys-act-guidelines. Accessed 20 Oct 2015.

Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods. 2008;40:879–91.

Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Predicting and changing behavior: the reasoned action approach. New York: Taylor & Francis; 2010.

Scholz U, Schuz B, Ziegelmann JP, Lippke S, Schwarzer R. Beyond behavioral intentions: planning mediates between intentions and physical activity. Br J Health Psychol. 2008;13:479–94.

Belanger-Gravel A, Godin G, Armireault S. A meta-analytic review of the effect of implementation intentions on physical activity. Health Psychol Rev. 2013;7:23–54.

Webb TL, Sheeran P. Does changing behavioral intentions engender behavior change? A meta-analysis of the experimental evidence. Psychol Bull. 2006;132:249–68.

Koring M, Richert J, Parschau L, Ernsting A, Lippke S, Schwarzer R. A combined planning and self-efficacy intervention to promote physical activity: a multiple mediation analysis. Psychol Health Med. 2012;17:488–98.

Wiedemann AU, Schuz B, Sniehotta FF, Scholz U, Schwarzer R. Disentangling the relation between intentions, planning, and behavior: a moderated mediation analysis. Psychol Health. 2009;24:67–79.

Pinto BM. Home-based physical activity intervention for breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3577–87.

Wang Y-J, Boehmke M, Wu Y-WB, Dickerson SS, Fisher N. Effects of a 6-week walking program on taiwanese women newly diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2011;34:E1–E13.

Anderson ES, Winett RA, Wojcik JR, Williams DM. Social cognitive mediators of change in a group randomized nutrition and physical activity intervention: social support, self-efficacy, outcome expectations and self-regulation in the Guide-to-Health trial. J Health Psychol. 2010;15:21–32.

Ligibel JA, Meyerhardt J, Pierce JP, Najita J, Shockro L, Campbell N, et al. Impact of a telephone-based physical activity intervention upon exercise behaviors and fitness in cancer survivors enrolled in a cooperative group setting. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;132:205–13.

Demark-Wahnefried W, Clipp E, McBride C, Lobach D, Lipkus I, Peterson B, et al. Design of FRESH START: a randomized trial of exercise and diet among cancer survivors. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35:415–24.

Demark-Wahnefried W, Clipp EC, Lipkus IM, Lobach D, Snyder DC, Sloane R, et al. Main outcomes of the FRESH START trial: a sequentially tailored, diet and exercise mailed print intervention among breast and prostate cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2709–18.

Rogers LQ, Markwell S, Hopkins-Price P, Vicari S, Courneya K, Hoelzer K, et al. Reduced barriers mediated physical activity maintenance among breast cancer survivors. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2011;33:235–54.

Ashford S, Edmunds J, French DP. What is the best way to change self-efficacy to promote lifestyle and recreational physical activity? A systematic review with meta-analysis. Br J Health Psychol. 2010;15:265–88.

Lubans DR, Plotnikoff RC, Jung M, Eves N, Sigal R. Testing mediator variables in a resistance training intervention for obese adults with type 2 diabetes. Psychol Health. 2012;12:1388–404.

Plotnikoff RC, Lubans DR, Penfold CM, Courneya KS. Testing mediator variables in a physical activity intervention for women with type 2 diabetes. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2014;15:1–8.

Spink KS, Nickel D. Self-regulatory efficacy as a mediator between attributions and intention for health-related physical activity. J Health Psychol. 2010;15:75–84.

Olander EK, Fletcher H, Williams S, Atkinson L, Turner A, French DP. What are the most effective techniques in changing obese individuals’ physical activity self-efficacy and behavior: a systematic revew and meta-analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2013;10:29.

Lubans DR, Morgan PJ, Callister R, Collins CE, Plotnikoff RC. Exploring the mechanisms of physical activity and dietary behavior change in the program X intervention for adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2010;47:83–91.

Ayotte B, Margrett J, Hicks-Patrick J. Physical activity in middle-aged and young-old adults: the roles of self-efficacy, barriers, outcome expectancies, self-regulatory behaviors and social support. J Health Psychol. 2010;15:173–85.

Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee J-Y, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88:879–903.

Parschau L, Richert J, Koring M, Ernsting A, Lippke S, Schwarzer R. Changes in social-cognitive variables are associated with stage transitions in physical activity. Health Educ Res. 2012;27:129–40.

Teixeira PJ, Carraca EV, Markland D, Silva MN, Ryan RM. Exercise, physical activity, and self-determination theory: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012;9:78.

French DP. The role of self-efficacy in changing health-related behavior: cause, effect or spurious association? Br J Health Psychol. 2013;18:237–43.

Cerin E, Barnett A, Baranowski T. Testing theories of dietary behavior change in youth using the mediating variable model with intervention programs. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2009;41:309–18.

Michie S, Prestwich A. Are interventions theory-based? Development of a theory coding scheme. Health Psychol. 2010;29:1–8.

Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, Abraham C, Francis J, Hardeman W, et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2013;46:81–95.

Greaves CJ, Sheppard KE, Abraham C, Hardeman W, Roden M, Evans PH, et al. Systematic review of reviews of intervention components associated with increased effectiveness in dietary and physical activity interventions. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:119.

Michie S, Abraham C, Whittingham C, McAteer J, Gupta S. Effective techniques in healthy eating and physical activity interventions: a meta-regression. Health Psychol. 2009;28:690–701.

Courneya KS, Plotnikoff RC, Hotz SB, Birkett NJ. Social support and the theory of planned behavior in the exercise domain. Am J Health Behav. 2000;24:300–8.

Plotnikoff RC, Blanchard C, Hotz SB, Rhodes R. Validation of the decisional balance scales in the exercise domain from the transtheoretical model: a longitudinal test. Meas Phys Educ Exerc Sci. 2001;5:191–206.

Acknowledgements

The ENRICH study was supported by funding from the Australian Better Health Initiative: A joint Australian, State and Territory government initiative with additional funding and infrastructure support provided by the Cancer Council NSW and Hunter Medical Research Institute.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

EJ, KC conceptualized the ENRICH trial and obtained funding. EJ, KC, DL, FS provided detailed input into the methods. DL, FS conceptualized and undertook the analysis for this paper. FS drafted the manuscript. All authors assisted with interpretation of the findings. All authors read and approved of the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Stacey, F.G., James, E.L., Chapman, K. et al. Social cognitive theory mediators of physical activity in a lifestyle program for cancer survivors and carers: findings from the ENRICH randomized controlled trial. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 13, 49 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-016-0372-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-016-0372-z