Abstract

Purpose

This study aims to quantify trajectories of overall health pre- and post-diagnosis of cancer, trajectories of overall health among cancer-free individuals, and factors affecting overall health status.

Methods

Overall health status, derived from self-rated health report, of Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities cohort participants diagnosed with incident cancer [lung (n = 400), breast (n = 522), prostate (n = 615), colorectal (n = 303)], and cancer-free participants (n = 11,634) over 19 years was examined. Overall health was evaluated in two ways: (1) overall health was assessed until death or follow-up year 19 (survivorship model) and (2) same as survivorship model except that a self-rated health value of zero was used for assessments after death to follow-up year 19 (cohort model). Mean overall health at discrete times was used to generate overall health trajectories. Differences in repeated measures of overall health were assessed using linear growth models.

Results

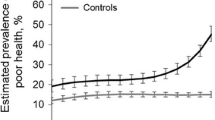

Overall health trajectories declined dramatically within one-year of cancer diagnosis. Lung, breast, and colorectal cancer were associated with a significant decreased overall health score (β) compared to the cancer-free group (survivorship model: lung—7.00, breast—3.97, colorectal—2.12; cohort model: lung—7.63, breast—5.07, colorectal—2.30). Other predictors of decreased overall health score included low education, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and age.

Conclusions

All incident cancer groups had declines in overall health during the first year post-diagnosis, which could be due to cancer diagnosis or intensive treatments. Targeting factors related to overall health declines could improve health outcomes for cancer patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Foraker RE, Rose KM, Chang PP et al (2011) Socioeconomic status and the trajectory of self-rated health. Age Ageing 40:706–711

Reeve BB, Potosky AL, Smith AW et al (2009) Impact of cancer on health-related quality of life of older Americans. J Natl Cancer Inst 101:860–868

Staren ED, Gupta D, Braun DP (2011) The prognostic role of quality of life assessment in breast cancer. Breast J 17:571–578

Osthus AA, Aarstad AK, Olofsson J, Aarstad HJ (2011) Health-related quality of life scores in long-term head and neck cancer survivors predict subsequent survival: a prospective cohort study. Clin Otolaryngol 36:361–368

Reeve BB, Stover AM, Jensen RE et al (2012) Impact of diagnosis and treatment of clinically localized prostate cancer on health-related quality of life for older Americans: a population-based study. Cancer 118:5679–5687

Gray NM, Hall SJ, Browne S et al (2011) Modifiable and fixed factors predicting quality of life in people with colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer 104:1697–1703

Singh-Manoux A, Dugravot A, Shipley MJ et al (2007) The association between self-rated health and mortality in different socioeconomic groups in the GAZEL cohort study. Int J Epidemiol 36:1222–1228

Wolinsky FD, Tierney WM (1998) Self-rated health and adverse health outcomes: an exploration and refinement of the trajectory hypothesis. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 53:S336–S340

Kennedy BS, Kasl SV, Vaccarino V (2001) Repeated hospitalizations and self-rated health among the elderly: a multivariate failure time analysis. Am J Epidemiol 153:232–241

Wolinsky FD, Miller TR, Malmstrom TK et al (2008) Self-rated health: changes, trajectories, and their antecedents among African Americans. J Aging Health 20:143–158

Idler EL, Benyamini Y (1997) Self-rated health and mortality: a review of twenty-seven community studies. J Health Soc Behav 38:21–37

The ARIC Investigators (1989) The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study: design and objectives. Am J Epidemiol 129:687–702

Diehr P, Patrick DL (2003) Trajectories of health for older adults over time: accounting fully for death. Ann Intern Med 139:416–420

Kucharska-Newton AM, Rosamond WD, Mink PJ, Alberg AJ, Shahar E, Folsom AR (2008) HDL-cholesterol and incidence of breast cancer in the ARIC cohort study. Ann Epidemiol 18:671–677

Diehr P, Williamson J, Patrick DL, Bild DE, Burke GL (2001) Patterns of self-rated health in older adults before and after sentinel health events. J Am Geriatr Soc 49:36–44

Baecke JA, Burema J, Frijters JE (1982) A short questionnaire for the measurement of habitual physical activity in epidemiological studies. Am J Clin Nutr 36:936–942

Rice NE, Lang IA, Henley W, Melzer D (2010) Baby boomers nearing retirement: the healthiest generation? Rejuvenation Res 13:105–114

Littell RC, Stroup WW, Freund RJ (2002) SAS for linear models, 4th edn. SAS Institute, Cary

Johnson M (2002) Individual growth analysis using PROC MIXED. SAS User Group International. 27

Latham K, Peek CW (2013) Self-rated health and morbidity onset among late midlife U.S. adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 68:107–116

Weaver DL, Rosenberg RD, Barlow WE et al (2006) Pathologic findings from the breast cancer surveillance consortium: population-based outcomes in women undergoing biopsy after screening mammography. Cancer 106:732–742

Howlader N NA, Krapcho M, Neyman N, Aminou R, Altekruse SF, Kosary CL, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Cho H, Mariotto A, Eisner MP, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Cronin KA (eds). SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2009 (Vintage 2009 Populations). National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD

Coyte A, Morrison DS, McLoone P (2014) Second primary cancer risk—the impact of applying different definitions of multiple primaries: results from a retrospective population-based cancer registry study. BMC Cancer 14:272

Brawley OW (2012) Prostate cancer epidemiology in the United States. World J Urol 30:195–200

Welch HG, Black WC (2010) Overdiagnosis in cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 102:605–613

Grutters JP, Joore MA, Wiegman EM et al (2010) Health-related quality of life in patients surviving non-small cell lung cancer. Thorax 65:903–907

Garrison CM, Overcash J, McMillan SC (2011) Predictors of quality of life in elderly hospice patients with cancer. J Hosp Palliat Nurs 13:288–297

Meropol NJ, Egleston BL, Buzaglo JS et al (2008) Cancer patient preferences for quality and length of life. Cancer 113:3459–3466

Silvestri G, Pritchard R, Welch HG (1998) Preferences for chemotherapy in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer: descriptive study based on scripted interviews. BMJ 317:771–775

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff and participants of the ARIC study for their important contributions and Dr. Christy Avery for her statistical expertise. Cancer incidence data have been provided by the Maryland Cancer Registry, Center for Cancer Surveillance and Control, Department of Mental Health and Hygiene, 201 W. Preston Street, Room 400, Baltimore, MD 21201. We acknowledge the State of Maryland, the Maryland Cigarette Restitution Fund, and the National Program of Cancer Registries (NPCR) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for the funds that helped support the availability of the cancer registry data. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study is carried out as a collaborative study supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute contracts (HHSN268201100005C, HHSN268201100006C, HHSN268201100007C, HHSN268201100008C, HHSN268201100009C, HHSN268201100010C, HHSN268201100011C, and HHSN268201100012C). Studies on cancer in ARIC are also supported by the National Cancer Institute (U01 CA164975-01). The content of this work is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Petrick, J.L., Foraker, R.E., Kucharska-Newton, A.M. et al. Trajectory of overall health from self-report and factors contributing to health declines among cancer survivors. Cancer Causes Control 25, 1179–1186 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-014-0421-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-014-0421-3