Abstract

Early detection of viral pathogens by DNA-sensors in clinical samples, contaminated foods, soil or water can dramatically improve clinical outcomes and reduce the socioeconomic impact of diseases such as COVID-19. Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR) and its associated protein Cas12a (previously known as CRISPR-Cpf1) technology is an innovative new-generation genomic engineering tool, also known as ‘genetic scissors’, that has demonstrated the accuracy and has recently been effectively applied as appropriate (E-CRISPR) DNA-sensor to detect the nucleic acid of interest. The CRISPR-Cas12a from Prevotella and Francisella 1 are guided by a short CRISPR RNA (gRNA). The unique simultaneous cis- and trans- DNA cleavage after target sequence recognition at the PAM site, sticky-end (5–7 bp) employment, and ssDNA/dsDNA hybrid cleavage strategies to manipulate the attractive nature of CRISPR–Cas12a are reviewed. DNA-sensors based on the CRISPR-Cas12a technology for rapid, robust, sensitive, inexpensive, and selective detection of virus DNA without additional sample purification, amplification, fluorescent-agent- and/or quencher-labeling are relevant and becoming increasingly important in industrial and medical applications. In addition, CRISPR-Cas12a system shows great potential in the field of E-CRISPR-based bioassay research technologies. Therefore, we are highlighting insights in this research direction.

Graphical Abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

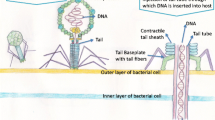

It is estimated that there are ten nonillions (1031) individual viruses on our planet, and more than 7000 viral genotypes have been extensively studied and described [1,2,3,4]. A virus is an infectious pathogen agent of a non-cellular structure that cannot reproduce outside the host cell. Replication of the viral genome occurs only inside the living (host) cells. They are infectious agents that can infect any cellular organism (prokaryotic, eukaryotic, and archaea) [5,6,7,8,9]. Furthermore, viruses are found in almost every ecosystem on the planet. However, viruses are smaller than bacteria, making them impossible to see under a light microscope, using only electron microscopes (cryo-electron microscopes, transmission electron microscopes) or X-rays to visualize them [10]. Moreover, the origin of the viruses has not been elucidated because they do not form fossils [11], but molecular technology has been most helpful in exploring their origin and creating a classification. However, since 1892 [12], the classification of viruses has changed several times. André Lwoff, Robert Horne, and Paul Tournier [13] were the first who develop a virus classification tool based on the Linnaean hierarchical system. In 1966 when the International Committee on Viral Taxonomy (ICTV) was established, the Baltimore [14] classification system began to be used as a traditional hierarchy of viruses. In most cases, viruses can be grouped according to their genetic material: DNA or RNA.

DNA viruses (herpes viruses, smallpox viruses, adenoviruses, human papillomaviruses, pararetro viruses, Etc.) are responsible for the most significant viral infections. The genome of DNA viruses is based on deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), and their replication, transcription, and immunization involve DNA-modifying enzymes (DNA polymerases, Reverse Transcriptase, CRISPR-Cas, Etc.) [15], initially can be present in the virus hosting cell and/or possessed by a virus [16,17,18]. Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) together with a CRISPR associated protein (Cas) and guided by short CRISPR RNA (gRNA) acts as an ‘immune’ and/or antiviral system of prokaryotic organisms such as bacteria and archaea [19]. However, DNA viruses are very often infecting both prokaryotic and eukaryotic microorganisms and, therefore, the genome of DNA viruses is diverse [18].

The genomes of DNA viruses, which can be single-stranded (ssDNA) or double-stranded (dsDNA), encode only a few genes (proteins) [20,21,22,23]. An infectious particle of a virus called a virion consists of a nucleic acid surrounded by a proactive layer of a capsid protein. Capsid (diameter of 20 to 300 nm) [24] is the protein envelope of the virus that encloses its genetic material. It consists of several oligomeric (repeating) structural units made from proteins called protomers. Protomers are made up of identical protein subunits called capsomeres. Viral genomes are circular, as in polar viruses, linear, and adenoviruses [25,26,27]. Most viruses control cellular mechanisms for macromolecular synthesis in the late phase of infection, directing it to synthesize large amounts of viral mRNAs and proteins rather than thousands of normal cellular macromolecules. Viruses often express proteins that modify host cell processes to maximize viral replication [28,29,30,31]. In many cases, the replication of the viral genome of most DNA viruses takes place in the cell nucleus, and here, viruses are completely dependent on host cell DNA synthesis processes. In other cases, DNA viruses from larger genomes can encode most of this cell mechanism by themselves [32]. In eukaryotes, the viral genome must pass through the cell nucleus membrane to reach these metabolic processes, and in bacteria, it must only enter the cell [33,34,35,36]. However, viruses use vital metabolic pathways in host cells for replication, making them challenging to eliminate from living organisms without drugs that typically cause toxicity to host cells. The most effective medical approaches to viral diseases are immune-to-infectious vaccines and antiviral drugs that selectively interfere with viral replication. Therefore, early detection of viral pathogens by sensitive bioassay methods in clinical samples, contaminated foods, soil, or water can significantly improve clinical outcomes and reduce the socioeconomic impact of viral diseases.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) [37], next-generation sequencing (NGS) [38, 39], enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) [40] are currently the most widely used “gold standard” methods, which are applied for the detection and identification of viral DNA in clinical practice [41,42,43]. Therefore, during the recent epidemic of COVID-19 [44, 45], it is especially relevant to develop a new method or to adapt/optimize other specific, sensitive, rapid, inexpensive, accurate, already applicable techniques for early detection of a nucleic acid of interest in specific and environmentally friendly methods.

Many of the applicable properties listed above are suitable for biosensors based on enzymatic reactions and electrochemical signal determination methods. Electrochemical response-based biosensing platforms are widely used due to their fast performance, affordable system, relatively simple sensing procedures, and direct determination of analytes [46]. One of the critical challenges for such a system is accuracy. However, the applicability of various enzymes combined with inorganic (silica [47], gold [48,49,50], carbon [51, 52]) nanoparticles for biosensor design has been successfully evaluated in many types of research [51, 53,54,55,56,57]. These studies have shown that biosensors combined with enzymes and gold-nanomaterials increase the bioassay system's accuracy, specificity, sensitivity, and selectivity [58, 59]. Hence, gold-based nanomaterials have demonstrated good performance in many applications and may be an attractive candidate for developing a CRISPR-Cas12a based system for several reasons. Gold nanoparticles are stable material, and it is easier to control particle size and composition by synthesis [60, 61]. The most advantageous property of the gold-based nanomaterial is their biocompatibility with various biomolecules [62]. Therefore, gold-based nanomaterials can be used the further developments of biosensors based on DNA- and RNA-modifying enzymes.

Some reviews on CRISPR-Cas diversity, classification, and evolution have been published over the last three years [63,64,65]. In 2017, to systematize the classification, all complex encoded effector proteins and representatives have been divided into two classes (class 1 and 2), types I-VI, and more than 30 subtypes. Typical class 1 CRISPR-Cas system members are based on a complex of 4–7 Cas proteins (several Cas proteins and crRNAs bind together and form a functional endonuclease). Members this class 1 are widespread in bacteria (including hyperthermophiles) and archaea. Members of the class 2 CRISPR-Cas system use a single multidomain effector protein (uses a single Cas protein with crRNA) and are widespread only in bacteria. Unlike other classes, candidates of the CRISPR-Cas class 2 system (Cas9, Cas12, Cas13) are the most common and best-studied and are described and named as the best candidates for the development of genome editing tools suitable for applications in vivo and in vitro [66].

This review purposely shows and discusses previous research of CRISPR-Cpf1 (Cas12a) and even provides possible ideas for further development. The study addresses the attractiveness of the CRISPR-Cas12a system for simultaneous cis-(target) and trans-(non-target) DNA cleavage, sticky-end (5–7 bp) employment for the development of potential versatile electrochemical biosensing platforms (E-CRISPR) as DNA-sensors for the verification of single-stranded and double-stranded DNA virus-induced infections and the discovery of any other DNA-targets.

Main

CRISPR-Cas action mechanism

The CRISPR [67] is a genomic region in the prokaryotic cell where genetic information about adaptive immunity is stored. The system was discovered in E. coli in 1987 [68]. More technically, the CRISPR system comprises regularly recurring palindromic sequence inserts in the genomic region (Fig. 1a). The palindromic repeats in the prokaryotic genomic region consist of about 21–40 bp, and regular DNA spacer repeats are about 20–58 bp in length [69]. In the prokaryotic cell CRISPR genomic region, Cas protein is responsible for preserving living cell genetic information [70,71,72]. In 2007 [73], several in vitro and in vivo studies have shown that the CRISPR-Cas complex acts as an antivirus system in a prokaryotic cell—it detects genetic information from foreign species (e.g., viruses) stores and destroys them in a particular and specific way. Astonishingly, in a prokaryotic cell, the mechanism of action of the antiviral system is efficient and straightforward. When the foreign species attacks the prokaryotic cell, these viruses' genome (RNA, DNA, or plasmids) is injected into the prokaryotic cell. Due to the CRISPR-Cas system, a short piece of foreign species genome information is taken and stored in the memory (locus) of prokaryotic cells, and later it can prevent the cell from repeated attacks by the same strain of viruses. Naturally, in the prokaryotic cell, protection from the foreign genome system is based on three stages of action: adaptation, expression, and interference (Fig. 1d) [74, 75].

Performance of basic CRISPR-Cas system: a Overview of schematic CRISPR definition; b Cas proteins are nucleases, endoribonucleases, helicases, or/and integrases: (1) single-strand DNA (break) by nuclease activity; (2) double-strand DNA (break) by nuclease activity; (3) double-strand DNA unwinding by helical activity; c Structure of Cas protein, guide RNA (crRNA) and target DNA complex; d Performance of four-part CRISPR-Cas action mechanism in the prokaryotic cell: 1. Stage—adaptation; 2–3. Stages—expression; 4. Stage—interference

The immunization and interference in prokaryotic cells

The primary mechanism of CRISPR-Cas action was defined by Brouns et al. [76], McGinn et al. [77], Yan et al. [78] and Siksnys et al. [79,80,81,82]. The Cas enzyme complex (which always requires Cas1 and Cas2) in the prokaryotic cell is involved in the natural metabolic process during the adaptation stage (Fig. 1d). Incredibly, in the Cas enzyme complex, Cas1 nuclease has integrase activity, and the Cas2 nuclease has endoribonuclease activity, which acts only together. This Cas complex recognizes short motifs (2–4 bp in length) adjacent to the protospacers [83,84,85]. Cas1 nuclease cleaves a piece of foreign species genome near the PAM and integrates it into the CRISPR locus, yielding a new spacer. In a prokaryotic cell, the CRISPR locus is the area where the peace of genetic information of infecting-foreign species is ‘preserved’ to protect cells from recurrent infections of the same infectious species), a CRISPR RNA is transcribed and processed into mature RNA (crRNA) [86, 87]. During the expression stage (Fig. 1d), a CRISPR RNA (crRNA) molecule is formed. One of the DNA strands with CRISPR locus is transcribed into mRNA (described in some references as pre-crRNA) [77, 88, 89]. mRNA becomes long and exactly complementary to DNA strand, containing repeats of many CRISPR complementary sequences and genomic sequences of foreign species. crRNA is formed from the transcribed mRNA. However, the final composition of crRNA also differs for different Cas types (I–III types). In the expression stage (type I), crRNA consists of one repeat of the CRISPR genome and one genome of a foreign species. Technically, each repetition of the CRISPR sequence forms a loop, but each repetition of the genome sequence of a foreign species does not form a loop, and subsequently, the Cas6e and Cas6f nucleases digest the crRNA. The transactivating CRISPR RNA (tracrRNA) molecule plays a crucial role in the type II process. Technically, the tracrRNA sequence is digested with Cas9 nuclease and RNase III. In the type III process, the Cas6 nuclease directly disrupts each repeat of the CRISPR sequence and the foreign species genome sequence (Fig. 1d) [78, 90]. In the interference stage (Fig. 1d), specially encoded crRNA (as a guide-RNA) is integrated into the Cas protein and forms the CRISPR-Cas complex [91]. In the combined system, the CRISPR-Cas complex contains genomic information from the foreign species recorded into crRNA that allows the foreign genome's identification, detection, and inactivation. This antiviral mechanism works in prokaryotic cells.

Following the present invention, bioengineered CRISPR-Cas systems have been implemented in industries that exploit bacterial cultures (dairy products, agriculture, Etc.) to establish the ability to protect a bacterial culture from virus attack [73, 92,93,94]. Later, in 2014, the CRISPR-Cas system was adjusted as a powerful tool for genomic research to silence and/or edit gene sequences with additional effectors in various organisms [85, 95,96,97]. Initial studies in bacterial cell lines [98, 99] and mammalian cells [100,101,102,103,104] have shown that the biologically engineered CRISPR-Cas technology has future potential for correcting gene mutations. Such as malaria blocking genes in mosquitoes [105,106,107,108,109,110], genome editing in zebrafish [111,112,113], removing HIV genes [64, 114,115,116], hepatitis C virus [117] or Parkinson’s disease [118]. However, this exciting progress may have unintended consequences and impacts due to ‘off-target’ effects, which recently are the main limitations of the CRISPR-Cas system because applied genetic corrections can have unpredictable results for future generations. Nevertheless, some developers of the CRISPR-Cas system (Emmanuelle Charpentier and Jennifer A. Doudna) have been awarded by Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2020 [119] and the CRISPR-Cas system has become a new generation of genomic engineering tools.

Furthermore, due to urgent need, chased by pandemics and pathogenic viruses has increased the demand for rapid, accurate, low-cost nucleic acid detection methods, and the studies have shown how the CRISPR-Cas (including Cas12a) combination in DNA Endonuclease-Targeted CRISPR Trans-Reporter (DETECTR) [120], one-Hour Low-cost Multipurpose highly Efficient System (HOLMES) [121] assays can be adapted to become an excellent biomedical diagnostics tool.

Potentials and limitation of CRISPR-Cas12a

A new potential for the Class 2 CRISPR-Cas system is the Cas12a member (CRISPR from Prevotella and Francisella 1), which consists of 1300 amino acid residues. This 151 kDa monomeric protein enhances the application of CRISPR systems to genomic engineering [122]. Recently, an opportunity came to follow the crystal structure variants of the Acidaminococcus sp. (AsCpf1), which was evaluated by McMahon et al. and Dong et al. [66, 123] and Lachnospiraceae bacterium (LbCpf1) evaluated by Safari et al. [124], Jiménez et al. [125] and Swarts et al. [126]. Structural and functional differences in Cas9 and Cas12a were reported [127]. However, the primary key points are that since other class 2 (Cas9, Cas13) candidates Cas12a can be reprogrammed to recognize the target dsDNA sites. A single crRNA guides Cas12a and for cleavage, no tracrRNA is required [128, 129]. Furthermore, Cas12a recognizes the T-rich PAM (5′-TTTV-3′) site by guided crRNA, and another essential distinguishing feature of Cas12a-crRNA is that it can also be directed to suboptimal PAMs (5′-TTV-3′, 5′-TCTV-3′, 5′-TCCV-3′, and 5′-CCCV-3′) sites (Fig. 2a). Moreover, due to these PAM benefits or limitations, Gao and co-authors [130,131,132,133,134,135] have shown that science can modify robust evolutionary theories and adapt to alternative PAM sequences to increase its targeting range for the CRISPR-Cas12a system, but of course, with a lower cleavage efficiency rate. After the identification of the PAM site, CRISPR-Cas12a cleaves (42–44 bp) target (cis-) double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) of the target at 37 °C temperature and generates sticky ends (5–7 bp) near the PAM target site—this is another essential attribute of Cas12a (Fig. 2a). Hence, the CRISPR-Cas12a is different from other CRISPR-Cas systems identified as additional non-target (trans-) cleavage activity (Fig. 2b), and the protein-based part CRISPR-Cas12a is smaller than that of Cas9. Therefore, the formation of the CRISPR-Cas12a complex with crRNA is remarkably more uncomplicated. The complex formed is smaller, and crRNA forms only one loop. Furthermore, Cas12a has a protospacer (24 bp) and is more specific because Cas12a has a lower intrinsic tolerance for crRNA-target DNA mismatches and requires higher complementarity. The RuvC domain (lysine residue) is responsible for target cleavage, but differently from some other Cas representatives, Cas12a lacks the detectable second endonuclease domains (HNH) [136,137,138].

CRISPR-Cas12a resembles the beak structure: the active center is suppressed in the closed position, and the active center is released—in the open position. The a N-terminal recognition (REC) region is divided into two [Rec1 (13 α helices) and Rec2 (10 α helices and 2 β strands)] alpha-helical domains that form an antiparallel sheet at the top of the structure. The C-terminal NUC lobe is divided into Wedge [WED (7 α helices and 2 β strands)], PAM-interacting [PI (7 α helices and β hairpin)] and an endonuclease domain involved in DNA repair RuvC (three motifs (RuvC I–III), which form active endonuclease center) and Nuc at the bottom of the structure. Modified bridge helix (BH consist of Arg951 and Arg955 which interact with the phosphate backbone of the target DNA strand) region is in the middle of NUC and REC lobes. The cleavage mechanism: a cis-cleavage in RuvC domain; b cis- and trans-cleavages in RuvC domain; c E-CRISPR biosensor prototype based on CRISPR-Cas12a system: C1—target dsDNA detection by cis- cleavage when target dsDNA is immobilized on AuNP as analyte. C2—target dsDNA detection by trans-cleavage when ssDNA is immobilized on AuNP and dsDNA is analyte. C3—target dsDNA detection by trans-cleavage when CRISPR-Cas12a is immobilized on AuNP and dsDNA is analyte. C4—dsDNA detection by trans-cleavage and additional effector when ssDNA is immobilized on AuNP and dsDNA as analyte. The CRISPR-Cas12a system can be fused with some newly designed enzymes like polymerases, other nucleases, or fluorescent proteins as additional effectors. Afterward, modified Cas protein in the CRISPR-Cas system can be used to transport those effectors to a specific DNA sequence for transcription, specific hydrolysis, visualization, or another practical purpose target. Together, through the examples detailed above, we have illustrated integrating CRISPR-Cas systems into different types in vivo biological sensing scenarios as well as emerging monitoring points compassionate and selective diagnostic programs determination of nucleic acids, proteins, and other small molecules

CRISPR-Cas12a based quantitative kinetics analysis consists of the following physical and chemical steps: PAM recognition, dsDNA-target binding, R-loop formation (0.1 s−1), rejection, cleavage (1.45 min−1), and release between crRNA and dsDNA assisting Cas12a already established by Li et al. [54], Swarts et al. [139], Singh et al. [140] and Chen et al. [141].

Direct comparison as mentioned above is unique in the way that the CRISPR-Cas12a system at the RuvC domain has additional nonspecific (trans-) single-stranded DNA cleavage activities dependent on Mg2+ and Ca2+ ions (Fig. 2b) [139, 142, 143]. Recent studies [144,145,146,147] have shown that the additional cleavage phenomenon is induced in rapid and complete cleavage of the ssDNA strand when the ssDNA sequence is not complementary to crRNA or other strand sequences. Furthermore, the cleavage doesn’t relate to the dsDNA specific sequence. Technically, no additional PAM sequence is required for self-cleavage activation. After target dsDNA unwinding and cleavage during the ordinary CRISPR-Cas12a action, the RuvC domain becomes accessible, and the non-target ssDNA cleavage occurs spontaneously (Fig. 2b). The spontaneous cleavage indicates that activation of nonspecific ssDNA cleavage has happened in the presence of CRISPR-Cas12a target sequence for dsDNA recognition and cleavage (Fig. 2) [122, 148]. Moreover, in 2020 Christopher W. Smith and co-authors [149] research proved that this CRISPR-Cas12a trans-cleavage is not limited to ssDNA substrates, and Cas12a-based diagnostics can be extended to ssDNA/dsDNA hybrid substrates. Several variables of NaCl (50–150 mM) concentration and fluorescently silent ssDNA/dsDNA (0–12 bp nicked) hybrid substrates were applied in the bioassays to monitor CRISPR-Cas12a cis-(target) and trans-(non-target) activities. These studies have proved that CRISPR-Cas12a activity significantly reduced the increase in NaCl concentration. This CRISPR-Cas12a trans-ssDNA-cleavage activity offers a new strategy to improve transcription and replication responses in vivo, label ssDNA, or develop faster, more sensitive and specific tools for the determination of specific DNA sequences.

In the studies by Gootenberg et al. [150], Kim et al. [151] and Doudna et al. [152], both Cpf1 orthologs (AsCpf1—from Acidaminococcus sp. and LbCpf1—from Lachnospiraceae bacterium) have been applied in both (i) genome editing in vivo and (ii) DNA assembly in vitro. AsCpf1 and LbCpf1 differences were reviewed in 2007 by Kim et. al. [153] and Verwaal et. al. [154]. However, gene-editing studies in combination with CRISPR-Cas12a have shown the potential for ‘self-processing’. The system can be assembled into a single and relatively simple plasmid suitable for transfection into selected cells to manipulate selected genes. Therefore, the CRISPR molecular tool can detect selected nucleic acid sequences, target gene editing, and a new protein detection strategy. These benefits and unique features increase the attractiveness of the CRISPR-Cas12a system to develop various biotechnological and bioassay research tools [155].

Analytical applications of CRISPR-Cas12a

CRISPR-Cas systems for nucleic acid detection have been critically discussed by Li et al. [54], Zhang et al. [156], Doudna et al. [141], Gallego et al. [157], Gootenberg et al. [158], Bonini et al. [159], Collins et al. [160], Wang et al. [161] and other authors [145, 162,163,164,165,166,167,168,169,170,171,172,173,174,175,176]. Here, we review the main powerful, sensitive analytical methods of CRISPR-Cas: (i) fluorescence in situ hybridization (DNA-FISH) assay based CRISPR-Cas9 technique for specific targeting with SYBR green I as a fluorescent probe (detection limit 10 CFU/ml); (ii) CRISPR-Cas triggered isothermal exponential amplification reaction (CAS-EXPAR) based CRISPR-Cas9 technique and isothermal exponential amplification with SYBR green as a fluorescent probe for a large number of DNA generation and target DNA detection at attomole (aM) sensitivity; (iii) CRISPR rolling circular amplification (CRISPR-RCA) assay based CRISPR-Cas9 technique and rolling circle amplification with SYBR green as a fluorescent probe for a large number of DNA generation, amplification; (iii) DNA endonuclease-targeted CRISPR trans-reporter (DETECTR) and one-hour low-cost multipurpose highly efficient system (HOLMES) based CRISPR-Cas12a technique and target nucleic (DNA or RNA) is amplified with isothermal amplification by RPA (recombinase polymerase amplification) or reverse transcription RPA, the target cleavage fluorescence response generated by ssDNA fluorophore-quencher reporter, detection at attomole (aM) sensitivity; (iv) specific high sensitivity enzymatic reporter unlocking (SHERLOCK) system based CRISPR-C2c2 technique for RNA detection by fluorophore-quencher reporter release and emits fluorescence by RPA; (v) SHERLOCKv2—for nucleic acid sequences detection to applied single reaction by using different Cas enzymes mix (C2c2, Cpf1, Csm6) [177,178,179,180]. However, the main challenges in these applications mentioned above are additional purification of the sample, expensive labeling of the target with fluorophores, application of other amplification steps with expensive techniques, and data analysis, which requires practice and knowledge.

E-CRISPR application

Schematic comparison of Cas proteins in their native forms is detailed in publication by Patrick Schindele et al. [181]. The CRISPR-Cas9 system mediates its function through a single effector Cas9 and two small RNAs, crRNA and tracrRNA. After hybridization, the crRNAR- tracrRNA complex binds to the Cas9 nuclease and binds to its recognition site before the PAM sequence. DNA binding is promoted by a 20 nucleotide reference sequence of crRNA. Cas9 nuclease causes a blunt-ended DSB 3 bp before the PAM sequence. The recognition of the crRNA-tracrRNA-target complex is promoted by the REC (recognition) section, the PI (PAM interacting) domain is responsible for recognizing the PAM. The DSB is mediated by the HNH and RuvC nuclease domains, with the HNH domain cleaving the target and the RuvC domain cleaving the non-target chain. The CRISPR-Cas13 system (Cas13a) mediates its function through a single effector Cas13 and a single crRNA. By combining Cas13 and crRNA, the complex binds to its recognition site on the target RNA mediated by the crRNA sequence. The catalytic site is outside the protein, directed to the surrounding solution, hence, the target RNA is cleaved away from the recognition site. The recognition of the crRNA-target complex is promoted by the REC (recognition) section, the cleavage of the target RNA is performed by the HEPN domain. The CRISPR-Cas12a system mediates its function through a single effector Cas12a and crRNA. By combining Cas12a and crRNA, the complex binds to its recognition site downstream of the PAM sequence. DNA binding is promoted by a 23 to 25 nucleotide reference sequence of crRNA. Cas12a nuclease induces a stepwise DSB distal to the PAM sequence. The recognition of the crRNA-target complex is mediated by the REC (recognition) section, the PI (PAM interacting) domain is responsible for identifying the PAM.

New revolutionary research by Lee et al. [182], Zhang et al. [155] and Dai et al. [183] demonstrates a universal and straightforward endonuclease activity monitoring method with the micro-fabricated gold-working electrode-based three-electrode system, where E-CRISPR modifies the gold-working electrode. In 2020, the invented E-CRISPR method is based on CRISPR-Cas12a-mediated interface and ssDNA reporter cleavage. The authors declared that the E-CRISPR system is suitable for detecting key categories (ssDNA, dsDNA) of biomolecules, providing the potential for implementation in the healthcare industry. Moreover, the unique trans- cleavage nuclease activity allows the use of any ssDNA sequence labeled by fluorescence signal reporter, this part of the E-CRISPR system can be easily replaced by another ssDNA with a signal reporter and applied for the determination of selected ssDNA, dsDNA, or ssRNA. Therefore, this aspect ‘to make E-CRISPR-Cas12a system reprogrammable’ is very attractive.

The evolution of the E-CRISPR system has been demonstrated by applying virus DNA (Human papillomavirus, Parvovirus, Dengue viruses) and proteins (Transforming Growth Factor b1 (TGF-b1) protein, Collagen, Aggrecan, and Bovine Serum Albumin) [92, 184,185,186]. Virus dsDNA and protein conjugated (immobilized) with DNA aptamer electrochemical (E-CRISPR) detection of methylene blue conjugated to gold nanoparticles (MBAuNP) have been successfully developed and performed by electrochemical signal detection. The above research demonstrated the specificity of the E-CRISPR-Cas12a system at sufficient limits of detection. However, the detected LODs depend on the length and structure of the non-target (trans-) ssDNA strand and applied detection method. Recently, higher efficiencies (of 96%, at 30 pM LOD) were achieved when the ssDNA (of 32 bp length) was constructed in the hair-pin structure. The system additionally contained an RNases inhibitor and was performed by EIS method with Fe(CN)63−/4− as a mediator. If compared, the linear structure of ssDNA (32 bp) under the same reaction condition efficiency reaches 56%. Studies confirmed that the linear non-target ssDNA (18–40 bp in length) was immobilized on the carrier. Target DNA detection efficiency was achieved 30% due to electrochemical current outputs a detection method without Rnases inhibitors or crRNA modifiers. However, when comparing other biosensors based on the CRISPR-Cas12a system, the invented E-CRISPR system showed lower sensitivity due to several following issues. The system should first be well prepared for working with RNA, as RNA is highly unstable in ribonucleases in vivo (by tissue) and in vitro (environment) to achieve sensitivity in the electrochemical response. To achieve a higher sensitivity in recording electrochemical response, the system should first be well prepared. The RNA is highly unstable in the presence of ribonucleases in vivo (by tissue) and in vitro (environment), and the chemical modification of crRNA using phosphorothioate (PS), 2′-O-Methyl (2′-O-Me), 2′-Fluoro (2′-F), S-constrained ethyl (cEt) substitutions at the terminal 5′ or 3′ ends, or internal positions [187], or additional components such as RNase inhibitors should be involved into analytical system. As it is essential to eliminate RNases contamination and significantly increase metabolic stability and expression (in vivo), affinity, extend half-live of the system, mediate high levels of gene editing, or effectively determine the limit of detection by determining CRISPR-Cas12a methods. The Wei et al. [188] declare that the detection limit and the dynamic detection range of the E-CRISPR sensor can be further improved. The authors conducted more detailed comparative studies with the Cas12a and Cas9 systems to evaluate the effect of improving E-CRISPR sensor performance. The principle of the E-CRISPR sensor is the target induced conformational change of the surface signaling probe (containing an electrochemical tag), leading to the variation of the electron transfer rate of the electrochemical tag. To better understand the –trans cleavage efficiency, the authors investigated the effect of divalent cation (Mg2+) concentration in an in vitro degradation solution, as the catalytic domain of RuvC is known to act on nuclease activity based on a bimetallic ion mechanism. Futhermore, enhancement of the detection signal was observed with increasing Cas12a reaction process up to 1 h. The specific and complementarity-dependent enzymatic activity of CRISPR is exploited beyond the detection limit of conventional electrochemical DNA sensors and, most importantly, the detection accuracy [182, 188, 189].

Firstly, gRNA should be designed to be complementary to the target following a correct PAM sequence. Secondly, the Cas protein with crRNA should be constructed appropriately to recognize the PAM sequence in target nucleic acid, and after target (cis-) cleavage, the non-target (trans-) cleavage is activated. Due to the detection method of E-CRISPR based on non-target cleavage, the different duration time of a non-specific target cleavage differs, and the differences were investigated by Dai et al. [155] and Zhang et al. [187]. At the latest publication, a photoactive methylene blue dye, and biotin [182], were used by several authors, but it is hypothesized that some other redox probes (phenothiazines, ferrocenes, porphyrins, Etc.) can be applied to electrochemical [190] signal registration [189, 190].

CRISPR-Cas biosensing systems are suitable for developing CRISPR-Cas12a point-of-care (POC) test devices with performance equivalent to or better than conventional diagnostics practices. Sensitive and rapid detection of nucleic acids with the naked eye is a new direction in analytical diagnostics. For on-site diagnostics, an ssDNA reporter labeled with a quenched green fluorescent molecule cleaved by Cas12a was introduced, and the resulting green fluorescence can be seen with the naked eye or in 485 nm light [193,194,195]. Point-of-care testing (POCT) is advantageous in terms of its ease of use, greater approachability on the user's friendly, more timely detection, and comparable accuracy and sensitivity, which could reduce the testing load on central hospitals [196, 197].

The CRISPR-Cas system is programmable, modular, and a specific biological tool for genomic or tissue engineering, bioelectronics, and diagnostics [198]. The CRISPR system is an accessible and powerful tool for regulating biological sensing strategies based on a highly selective sensing mechanism as a functional response. Combining Cas protein with a graphene-based field-effect transistor (FET) has been reported femtomole (1.7 fM) sensitivity of designed analytical system towards target sequence. This was achieved within 15 min lasting action of the sensing system because an increasing amount of formed DNA significantly reduces the conductivity of modified FET-gate. In addition, charged phosphate groups involved in DNA structure affect the gate, and therefore current passing through FET is changing [199]. Some other authors reported that CRISPR-Cas as the programmable and modular tool could be integrated into a set of biosensors, as a nucleic acid-based system for a stem-loop enhanced sensitivity and selectivity through degradation activities [204], moreover, such systems can be applied for detecting various targets, including bacteria, viruses, cancer mutations, and others. High CRISPR-Cas potential in biological sensing technologies is constantly inspiring new research activities to develop a new generation of nucleic acid detection platforms. However, the drawback of CRISPR-Cas-based systems is related to the relatively low sensitivity of Cas protein. However, most CRISPR-Cas bio-sensitization methods can directly detect nucleic acid targets, which is beneficial in combination with appropriate DNA-amplification methods. Therefore, the most currently used CRISPR-Cas biosensing systems rely on the target nucleic acid amplification, which improves sensitivity. Therefore, this additional amplification step can create some additional drawbacks and can make the system less robust. In addition, CRISPR biological sensing techniques can only be used for known DNA detection sequences that may limit their application in some specific cases [54]. It should be noted that during the development of ‘hands-on diagnostic systems’, the development of the suitable strategy to immobilize CRISPR-Cas systems on various interfaces is one of the most challenging key issues.

Conclusions and future perspectives

The evolution of bioassay methods based on E-CRISPR-Cas12a can be unambiguously extended without any amplification or purification-based steps. CRISPR-Cas12a is an attractive tool for detecting non-target (trans-) ssDNA cleavage in electrochemical signal-based systems. In addition, after the cis-cleavage sticky ends (5–7 bp) in dsDNA are formed, this effect can be efficiently exploited to evolve ultrasensitive biosensors for target DNA detection. CRISPR-Cas12a has successfully demonstrated the potential to be applied in susceptible systems suitable for determining exceptional resolution and time efficiency in conjunction with simple visual signal readings and quantitative determination. However, the CRISPR system has additional potential application, which is still not tapped within bio-electroanalytical methods. We also are predicting that in the very near future, DNA-modifying enzymes, including recently very famous CRISPR-Cas9 and CRISPR-Cas12a systems, which are recently finding many applications for various genome-editing related purposes, will find comprehensive application in the design of ‘programmable DNA- and RNA-sensors.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

References

Breitbart M, Rohwer F. Here a virus, there a virus, everywhere the same virus? Trends Microbiol. 2005;5:278–84.

Liu DJ, Day LA. Pf1 virus structure: Helical coat protein and DNA with paraxial phosphates. Science. 1994;265:671–4.

Day AG, Bejarano ER, Buck KW, Burrell M, Lichtenstein CP. Expression of an antisense viral gene in transgenic tobacco confers resistance to the DNA virus tomato golden mosaic virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:6721–5.

Bochkarev A, Barawell JA, Pfuetzner RA, Bochkareva E, Frappier L, Edwards AM. Crystal structure of the DNA-binding domain of the Epstein-Barr virus origin-binding protein, EBNA1, bound to DNA. Cell. 1996;84:791–800.

Koonin EV, Senkevich TG, Dolja VV. Biology Direct The ancient Virus World and evolution of cells. 2006; http://www.biology-direct.com/content/1/1/29

Lawrence CM, Menon S, Eilers BJ, Bothner B, Khayat R, Douglas T, et al. Structural and functional studies of archaeal viruses. J Biol Chem. 2009;8:12599–603.

Chisari FV, Ferrari C, Mondelli MU. Hepatitis B virus structure and biology. Microb Pathog. 1989;23:311–25.

Liu S, Knafels JD, Chang JS, Waszak GA, Baldwin ET, Deibel MR, et al. Crystal structure of the herpes simplex virus 1 DNA polymerase. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:18193–200.

Noueiry AO, Lucas WJ, Gilbertson RL. Two proteins of a plant DNA virus coordinate nuclear and plasmodesmal transport. Cell. 1994;76:925–32.

Baker TS, Olson NH, Fuller SD. Adding the third dimension to virus life cycles: three-dimensional reconstruction of icosahedral viruses from cryo-electron micrographs. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2000;64:237–237.

Iyer LM, Balaji S, Koonin EV, Aravind L. Evolutionary genomics of nucleo-cytoplasmic large DNA viruses. Virus Res. 2006;117:156–84.

Ivanovsky DI, Beijerinck MW. Bacteriol Rev. 1972;36:135–45.

Lwoff A, Horne R, Tournier P. A system of viruses. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1962;27:51–5.

Fauquet CM, Fargette D. International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses and the 3,142 unassigned species. Virol J. 2005;2:64. https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-422X-2-64.

Dronina J, Bubniene US, Ramanavicius A. The application of DNA polymerases and Cas9 as representative of DNA-modifying enzymes group in DNA sensor design (review). Biosens Bioelectron. 2020;45:112867.

Payne S. Introduction to DNA Viruses Viruses. 2017;97:231–6.

Jiang D. ssDNA Mycoviruses. Reference Module in Life Sciences. New York: Elsevier; 2020.

Sanjuán R, Pereira-Gómez M, Risso J. Genome Instability in DNA Viruses Genome Stability: From Virus to Human Application. New York: Elsevier Inc.; 2016. p. 37–47.

Bhaya D, Davison M, Barrangou R. CRISPR-cas systems in bacteria and archaea: Versatile small RNAs for adaptive defense and regulation. Annu Rev Genet. 2011;45:273–97.

Knobler CM, Gelbart WM. Physical Chemistry of DNA Viruses. 2009; www.annualreviews.org

Ng TFF, Manire C, Borrowman K, Langer T, Ehrhart L, Breitbart M. Discovery of a Novel Single-Stranded DNA Virus from a Sea Turtle Fibropapilloma by Using Viral Metagenomics. J Virol. 2009;83:2500–9.

Xie Q, Suárez-López P, Gutiérrez C. Identification and analysis of a retinoblastoma binding motif in the replication protein of a plant DNA virus: requirement for efficient viral DNA replication. EMBO J. 1995;14:4073–82. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00079.x.

Bamford DH, Grimes JM, Stuart DI. What does structure tell us about virus evolution? Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2005;9:655–63.

Tang L, Johnson JE. Structural biology of viruses by the combination of electron cryomicroscopy and x-ray crystallography. Biochemistry. 2002;9:11517–24.

Wynne SA, Crowther RA, Leslie AGW. The crystal structure of the human hepatitis B virus capsid. Mol Cell Cell Press. 1999;3:771–80.

Bronkhorst AW, van Cleef KWR, Vodovar N, Agah I, Ince H, Blanc H, et al. The DNA virus Invertebrate iridescent virus 6 is a target of the Drosophila RNAi machinery. PNAS. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1207213109.

Grünewald K, Desai P, Winkler DC, Heymann JB, Belnap DM, Baumeister W, et al. Three-dimensional structure of herpes simplex virus from cryo-electron tomography. Science. 2003;302:1396–8.

Lodish H, Berk A, Zipursky SL, Matsudaira P, Baltimore D, Darnell J. Molecular Cell Biology. 4th ed. W. H: Freeman; 2000.

Sun Y, Parker MH, Weigele P, Casjens S, Prevelige PE, Krishna NR. Structure of the coat protein-binding domain of the scaffolding protein from a double-stranded DNA virus. J Mol Biol. 2000;297:1195–202.

Maul GG. Nuclear domain 10, the site of DNA virus transcription and replication. BioEssays. 1998. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199808)20:8<660::AID-BIES9>3.0.CO;2-M

Kraberger S, Cook CN, Schmidlin K, Fontenele RS, Bautista J, Smith B, et al. Diverse single-stranded DNA viruses associated with honey bees (Apis mellifera). Infect Genet Evol. 2019;71:179–88.

Fay N, Panté N. Nuclear entry of DNA viruses. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:467.

Caspr DL, Klug A. Physical principles in the construction of regular viruses. Cold Spring Harbor Symposia Quant Biol. 1962;27:1–24.

Gompels UA, Nicholas J, Lawrence G, Jones M, Thomson BJ, Martin MED, et al. The DNA sequence of human herpesvirus-6: structure, coding content, and genome evolution. Virology. 1995;209:29–51.

Straus SE, Aulakh HS, Ruyechan WT, Hay J, Casey TA, vande Woude GF, et al. Structure of varicella-zoster virus DNA. J Virol. 1981;40:9.

Fukuchi K, Sudo M, Lee YS, Tanaka A, Nonoyama M. Structure of Marek’s disease virus DNA: detailed restriction enzyme map. J Virol. 1984;51:102–5.

Higuchi R, Fockler C, Dollinger G, Watson R. Kinetic PCR analysis: Real-time monitoring of DNA amplification reactions. Bio/Technology. 1993;11:1026–30.

Straiton J, Free T, Sawyer A, Martin J. From Sanger sequencing to genome databases and beyond. BioTechniques Future Science. 2019;66:60–3. https://doi.org/10.2144/btn-2019-0011.

Behjati S, Tarpey PS. What is next generation sequencing? Archives of Disease in Childhood: Education and Practice Edition. BMJ Publishing Group; 2013 [cited 2020 Nov 30];98:236–8. /pmc/articles/PMC3841808/?report=abstract

Engvall E, Perlmann P. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay. Elisa. J Immunol. 1972;109:8.

Cheng TY, Buckley A, van Geelen A, Lager K, Henao-Díaz A, Poonsuk K, et al. Detection of pseudorabies virus antibody in swine oral fluid using a serum whole-virus indirect ELISA. J Veter Diagn Invest. 2020;32:535–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/1040638720924386.

Johansson Ö, Ullman K, Lkhagvajav P, Wiseman M, Malmsten J, Leijon M. Detection and genetic characterization of viruses present in free-ranging snow leopards using next-generation sequencing. Front Veter Sci. 2020;7:645. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2020.00645/full.

van Boheemen S, van Rijn AL, Pappas N, Carbo EC, Vorderman RHP, Sidorov I, et al. Retrospective validation of a metagenomic sequencing protocol for combined detection of RNA and DNA viruses using respiratory samples from pediatric patients. J Mol Diagn. 2020;22:196–207.

Dhamad AE, Abdal Rhida MA. COVID-19: Molecular and serological detection methods. PeerJ. 2020;8:e10180.

Chakraborty I, Maity P. COVID-19 outbreak: Migration, effects on society, global environment and prevention. Sci Total Environ. 2020;728:138882.

Morkvenaite-Vilkonciene I, Ramanaviciene A, Kisieliute A, Bucinskas V, Ramanavicius A. Scanning electrochemical microscopy in the development of enzymatic sensors and immunosensors. Biosens Bioelectr. 2019;8:111411.

Gomes NO, Carrilho E, Machado SAS, Sgobbi LF. Bacterial cellulose-based electrochemical sensing platform: A smart material for miniaturized biosensors. Electrochim Acta. 2020;349:89.

Tarhan T, Ulu A, Sariçam M, Çulha M, Ates B. Maltose functionalized magnetic core/shell Fe 3 O 4 @Au nanoparticles for an efficient L-asparaginase immobilization. Immune. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.09.116.

Yong Y, Bai Y, Li YF, Lin L, Cui Y, Xia C. Preparation and application of polymer-grafted magnetic nanoparticles for lipase immobilization. J Magn Magn Mater. 2008;320:2350–5.

Popov A, Brasiunas B, Damaskaite A, Plikusiene I, Ramanavicius A, Ramanaviciene A. Electrodeposited Gold Nanostructures for the Enhancement of Electrochromic Properties of PANI–PEDOT Film Deposited on Transparent Electrode. Polymers. 2020;12:2778.

Zhang H, Hua SF, Li C, Zhang L, Fan YC, Duan P. Effect of graphene oxide with different morphological characteristics on properties of immobilized enzyme in the covalent method. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng. 2020;23:6.

Barkauskas J, Mikoliunaite L, Paklonskaite I, Genys P, Petroniene JJ, Morkvenaite-Vilkonciene I, et al. Single-walled carbon nanotube based coating modified with reduced graphene oxide for the design of amperometric biosensors. Mater Sci Eng. 2019;98:515–23.

German N, Popov A, Ramanaviciene A, Ramanavicius A. Enzymatic formation of polyaniline, polypyrrole, and polythiophene nanoparticles with embedded glucose oxidase. Nanomaterials. 2019;9:806.

Li Y, Li S, Wang J, Liu G. CRISPR/Cas Systems towards Next-Generation Biosensing. Trends Biotechnol. 2019;8:730–43.

Li Z, Sheng W, Liu Q, Li S, Shi Y, Zhang Y, et al. Development of a gold nanoparticle enhanced enzyme linked immunosorbent assay based on monoclonal antibodies for the detection of fumonisin B1, B2, and B3 in maize. Anal Methods. 2018;10:3506–13.

Li J, Li Y, Zhai X, Cao Y, Zhao J, Tang Y, et al. Sensitive electrochemical detection of hepatitis C virus subtype based on nucleotides assisted magnetic reduced graphene oxide-copper nano-composite. Electrochem Commun. 2020;110:8.

Kausaite-Minkstimiene A, Glumbokaite L, Ramanaviciene A, Dauksaite E, Ramanavicius A. An amperometric glucose biosensor based on poly (pyrrole-2-carboxylic acid)/glucose oxidase biocomposite. Electroanalysis. 2018;30:1642–52. https://doi.org/10.1002/elan.201800044.

Newman JD, Setford SJ. Enzymatic biosensors. Mol Biotechnol. 2006;989:249–68. https://doi.org/10.1385/MB:32:3:249.

Rapp BE, Gruhl FJ, Länge K. Biosensors with label-free detection designed for diagnostic applications. Analyt Bioanalyt Chem. 2010. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00216-010-3906-2.

Nishida H, Kajisa T, Miyazawa Y, Tabuse Y, Yoda T, Takeyama H, et al. Self-oriented immobilization of DNA polymerase tagged by titanium-binding peptide motif. Langmuir. 2015;31:732–40.

Pingarrón JM, Yáñez-Sedeño P, González-Cortés A. Gold nanoparticle-based electrochemical biosensors. Electrochim Acta. 2008;53:5848–66.

German N, Popov A, Ramanaviciene A, Ramanavicius A. Formation and electrochemical characterisation of enzyme-assisted formation of polypyrrole and polyaniline nanocomposites with embedded glucose oxidase and gold nanoparticles. J Electrochem Soc. 2020;167:165501. https://doi.org/10.1149/1945-7111/abc9dc.

Shmakov S, Smargon A, Scott D, Cox D, Pyzocha N, Yan W, et al. Diversity and evolution of class 2 CRISPR-Cas systems. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2017;15:169–82.

Burstein D, Harrington LB, Strutt SC, Probst AJ, Anantharaman K, Thomas BC, et al. New CRISPR-Cas systems from uncultivated microbes. Nature. 2017;542:237–41.

Murugan K, Babu K, Sundaresan R, Rajan R. Sashital DG. The Revolution Continues: Newly Discovered Systems Expand the CRISPR-Cas Toolkit. Molecular Cell. Cell Press; 2017. p. 15–25.

McMahon MA, Prakash TP, Cleveland DW, Bennett CF, Rahdar M. Chemically Modified Cpf1-CRISPR RNAs mediate efficient genome editing in mammalian cells. Mol Therapy. 2018;26:1228–40.

Jansen R, van Embden JDA, Gaastra W, Schouls LM. Identification of genes that are associated with DNA repeats in prokaryotes. Mol Microbiol. 2002;43:1565–75. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02839.x.

Ishino Y, Shinagawa H, Makino K, Amemura M, Nakatura A. Nucleotide sequence of the iap gene, responsible for alkaline phosphatase isoenzyme conversion in Escherichia coli, and identification of the gene product. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:5429–33.

Ishino Y, Krupovic M, Forterre P. History of CRISPR-Cas from encounter with a mysterious repeated sequence to genome editing technology. J Bacteriol. 2018;200:17.

Garcia-Doval C, Jinek M. Molecular architectures and mechanisms of Class 2 CRISPR-associated nucleases. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2017;7:157–66.

van der Oost J, Westra ER, Jackson RN, Wiedenheft B. Unravelling the structural and mechanistic basis of CRISPR-Cas systems. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2014;9:479–92.

Sorek R, Lawrence CM, Wiedenheft B. CRISPR-Mediated Adaptive Immune Systems in Bacteria and Archaea. Ann Rev Biochem. 2013;82:237–66. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-biochem-072911-172315.

Barrangou R, Fremaux C, Deveau H, Richards M, Boyaval P, Moineau S, et al. CRISPR provides acquired resistance against viruses in prokaryotes. Science. 2007;315:1709–12.

Mohanraju P, Makarova KS, Zetsche B, Zhang F, Koonin E v., van der Oost J. Diverse evolutionary roots and mechanistic variations of the CRISPR-Cas systems. Science. 2016. http://science.sciencemag.org/. Accessed 16 Nov 2020.

Shmakov S, Abudayyeh OO, Makarova KS, Wolf YI, Gootenberg JS, Semenova E, et al. Discovery and Functional Characterization of Diverse Class 2 CRISPR-Cas Systems. Mol Cell. 2015;60:385–97.

Brouns SJJ, Jore MM, Lundgren M, Westra ER, Slijkhuis RJH, Snijders APL, et al. Small CRISPR RNAs guide antiviral defense in prokaryotes. Science. 2008;321:960–4.

McGinn J, Marraffini LA. Molecular mechanisms of CRISPR–Cas spacer acquisition. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2019;16:7–12.

Yan F, Wang W, Zhang J. CRISPR-Cas12 and Cas13: the lesser known siblings of CRISPR-Cas9. Cell Biol Toxicol. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10565-019-09489-1.

Sasnauskas G, Siksnys V. CRISPR adaptation from a structural perspective. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2020;23:17–25.

Gasiunas G, Sinkunas T, Siksnys V. Molecular mechanisms of CRISPR-mediated microbial immunity. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-013-1438-6.

Sapranauskas R, Gasiunas G, Fremaux C, Barrangou R, Horvath P, Siksnys V. The Streptococcus thermophilus CRISPR/Cas system provides immunity in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:9275–82.

Wilkinson M, Drabavicius G, Silanskas A, Gasiunas G, Siksnys V, Wigley DB. Structure of the DNA-Bound Spacer Capture Complex of a Type II CRISPR-Cas System. Mol Cell. 2019;75:90-101.e5.

Faure G, Shmakov SA, Yan WX, Cheng DR, Scott DA, Peters JE, et al. CRISPR–Cas in mobile genetic elements: counter-defence and beyond. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2019;17:513–25.

Gasiunas G, Young JK, Karvelis T, Kazlauskas D, Urbaitis T, Jasnauskaite M, et al. A catalogue of biochemically diverse CRISPR-Cas9 orthologs. Nat Commun. 2020;11:5512.

Glemzaite M, Balciunaite E, Karvelis T, Gasiunas G, Grusyte M, Alzbutas G, et al. Targeted gene editing by transfection of in vitro reconstituted streptococcus thermophilus cas9 nuclease complex. RNA Biol. 2015;12:1–4. https://doi.org/10.1080/15476286.2015.1017209.

Makarova KS, Wolf YI, Alkhnbashi OS, Costa F, Shah SA, Saunders SJ, et al. An updated evolutionary classification of CRISPR-Cas systems. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2015;13:722–36.

Gasiunas G, Barrangou R, Horvath P, Siksnys V. Cas9-crRNA ribonucleoprotein complex mediates specific DNA cleavage for adaptive immunity in bacteria. Bacteria. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1208507109.

Müller M, Lee CM, Gasiunas G, Davis TH, Cradick TJ, Siksnys V, et al. Streptococcus thermophilus CRISPR-Cas9 systems enable specific editing of the human genome. Mol Ther. 2016;24:636–44.

Makarova KS, Wolf YI, Iranzo J, Shmakov SA, Alkhnbashi OS, Brouns SJJ, et al. Evolutionary classification of CRISPR–Cas systems: a burst of class 2 and derived variants. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2020;8:67–83.

Gasiunas G, Barrangou R, Horvath P, Siksnys V. Cas9-crRNA ribonucleoprotein complex mediates specific DNA cleavage for adaptive immunity in bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:E2579–86. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1208507109.

Schindele P, Wolter F, Puchta H. Transforming plant biology and breeding with CRISPR/Cas9, Cas12 and Cas13. FEBS Lett. 2018;592:1954–67. https://doi.org/10.1002/1873-3468.13073%4010.1002/%28ISSN%291873-3468.reviews.

McMahon MA, Rahdar M, Porteus M. Gene editing: Not just for translation anymore. Nat Methods. 2012. p. 28–31. https://www.nature.com/articles/nmeth.1811

Cong L, Ran FA, Cox D, Lin S, Barretto R, Habib N, et al. Multiplex Genome Engineering Using CRISPR/Cas Systems. Science. 2013;339:819–23.

Mali P, Yang L, Esvelt KM, Aach J, Guell M, DiCarlo JE, et al. RNA-Guided Human Genome Engineering via Cas9. Science. 2013;339:823–6.

Doudna JA, Charpentier E. The new frontier of genome engineering with CRISPR-Cas9. Science. 2014;346:89.

Louwen R, Staals RHJ, Endtz HP, van Baarlen P, van der Oost J. The Role of CRISPR-Cas systems in virulence of pathogenic bacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2014;78:74–88.

Zhang F, Wen Y, Guo X. CRISPR/Cas9 for genome editing: Progress, implications and challenges. Hum Mol Genetics. 2014;23:R40–6.

Sternberg SH, Doudna JA. Expanding the Biologist’s Toolkit with CRISPR-Cas9. Mol Cell. 2015;2:568–74.

Hsu PD, Lander ES, Zhang F. Development and applications of CRISPR-Cas9 for genome engineering. Cell. 2014;23:1262–78.

Hur JK, Kim K, Been KW, Baek G, Ye S, Hur JW, et al. Targeted mutagenesis in mice by electroporation of Cpf1 ribonucleoproteins. Nat Biotechnol. 2016;8:807–8.

Kim Y, Cheong SA, Lee JG, Lee SW, Lee MS, Baek IJ, et al. Generation of knockout mice by Cpf1-mediated gene targeting. Nat Biotechnol. 2016;8:808–10.

Platt RJ, Chen S, Zhou Y, Yim MJ, Swiech L, Kempton HR, et al. CRISPR-Cas9 knockin mice for genome editing and cancer modeling. Cell Cell Press. 2014;159:440–55.

Ran FA, Cong L, Yan WX, Scott DA, Gootenberg JS, Kriz AJ, et al. In vivo genome editing using Staphylococcus aureus Cas9. Nature. 2015;520:186–91.

Liang P, Xu Y, Zhang X, Ding C, Huang R, Zhang Z, et al. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing in human tripronuclear zygotes. Protein Cell. 2015;6:363–72.

Schmidt H, Collier TC, Hanemaaijer MJ, Houston PD, Lee Y, Lanzaro GC. Abundance of conserved CRISPR-Cas9 target sites within the highly polymorphic genomes of Anopheles and Aedes mosquitoes. Nat Commun. 2020;11:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-15204-0.

Macias VM, McKeand S, Chaverra-Rodriguez D, Hughes GL, Fazekas A, Pujhari S, et al. Cas9-Mediated Gene-Editing in the Malaria Mosquito Anopheles stephensi by ReMOT Control. G3 (Bethesda Md). 2020;10:1353–60. https://doi.org/10.1534/g3.120.401133.

Adelman ZN, Tu Z. Control of Mosquito-Borne Infectious Diseases: Sex and Gene Drive. Trends Parasitol. 2016;9:219–29.

Chaverra-Rodriguez D, Macias VM, Hughes GL, Pujhari S, Suzuki Y, Peterson DR, et al. Targeted delivery of CRISPR-Cas9 ribonucleoprotein into arthropod ovaries for heritable germline gene editing. Nat Commun. 2018;9:1–11.

Hegde S, Nilyanimit P, Kozlova E, Anderson ER, Narra HP, Sahni SK, et al. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene deletion of the ompA gene in symbiotic Cedecea neteri impairs biofilm formation and reduces gut colonization of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13:e0007883. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0007883.

Burstein D, Harrington LB, Strutt SC, Probst AJ, Anantharaman K, Thomas BC, et al. New CRISPR–Cas systems from uncultivated microbes. Nature. 2016;542:237–41.

Fernandez JP, Vejnar CE, Giraldez AJ, Rouet R, Moreno-Mateos MA. Optimized CRISPR-Cpf1 system for genome editing in zebrafish. Methods. 2018;150:11–8.

Vejnar CE, Moreno-Mateos MA, Cifuentes D, Bazzini AA, Giraldez AJ. Optimized CRISPR-Cas9 system for genome editing in zebrafish. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2016;2016:856–70.

Zhang Y, Qin W, Lu X, Xu J, Huang H, Bai H, et al. Programmable base editing of zebrafish genome using a modified CRISPR-Cas9 system. Nat Commun. 2017;8:1–5.

Liu Z, Chen S, Jin X, Wang Q, Yang K, Li C, et al. Genome editing of the HIV co-receptors CCR5 and CXCR4 by CRISPR-Cas9 protects CD4+ T cells from HIV-1 infection. Cell Bioscience. 2017;7:1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13578-017-0174-2.

Park RJ, Wang T, Koundakjian D, Hultquist JF, Lamothe-Molina P, Monel B, et al. A genome-wide CRISPR screen identifies a restricted set of HIV host dependency factors. Nat Genet. 2017;49:193–203.

Kaminski R, Chen Y, Fischer T, Tedaldi E, Napoli A, Zhang Y, et al. Elimination of HIV-1 Genomes from Human T-lymphoid Cells by CRISPR/Cas9 Gene Editing. Sci Rep. 2016;6:1–15.

Jamehdor S, Zaboli KA, Naserian S, Thekkiniath J, Omidy HA, Teimoori A, et al. An overview of applications of CRISPR-Cas technologies in biomedical engineering. Folia Histochem Cytobiol. 2020;8:163–73.

Chai N, Haney MS, Couthouis J, Morgens DW, Benjamin A, Wu K, et al. Genome-wide synthetic lethal CRISPR screen identifies FIS1 as a genetic interactor of ALS-linked C9ORF72. Brain Res. 2020;1728:146601.

Ledford H, Callaway E. Pioneers of revolutionary CRISPR gene editing win chemistry Nobel. Nature. 2020;8:346–7.

Barrangou R. The roles of CRISPR-Cas systems in adaptive immunity and beyond. Curr Opin Immunol. 2015;23:36–41.

Li SY, Cheng QX, Li XY, Zhang ZL, Gao S, Cao RB, et al. CRISPR-Cas12a-assisted nucleic acid detection. Cell Discovery: Nature Publishing Groups; 2018.

Yamano T, Nishimasu H, Zetsche B, Hirano H, Slaymaker IM, Li Y, et al. Crystal Structure of Cpf1 in Complex with Guide RNA and Target DNA. Cell. 2016;165:949–62.

Dong D, Ren K, Qiu X, Zheng J, Guo M, Guan X, et al. The crystal structure of Cpf1 in complex with CRISPR RNA. Nature. 2016;532:522–6.

Safari F, Zare K, Negahdaripour M, Barekati-Mowahed M, Ghasemi Y. CRISPR Cpf1 proteins: Structure, function and implications for genome editing. Cell Biosci. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13578-019-0298-7.

Jiménez A, Hoff B, Revuelta JL. Multiplex genome editing in Ashbya gossypii using CRISPR-Cpf1. New Biotechnol. 2020;57:29–33.

Swarts DC, Jinek M. Cas9 versus Cas12a/Cpf1: Structure-function comparisons and implications for genome editing. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2018;9:e1481. https://doi.org/10.1002/wrna.1481.

Wang J, Zhang C, Feng B. The rapidly advancing Class 2 CRISPR-Cas technologies: A customizable toolbox for molecular manipulations. J Cell Mol Med. 2020;24:3256–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcmm.15039.

Gao L, Cox T, Yan WX, Manteiga JC, Schneider MW, Yamano T, et al. Engineered Cpf1 variants with altered PAM specificities. Nature. 2017;35:8.

Tao D, Liu J, Nie X, Xu B, Tran-Thi TN, Niu L, et al. Application of CRISPR-Cas12a enhanced fluorescence assay coupled with nucleic acid amplification for the sensitive detection of african swine fever virus. ACS Synth Biol. 2020;9:2339–50. https://doi.org/10.1021/acssynbio.0c00057.

Gao P, Yang H, Rajashankar KR, Huang Z, Patel DJ. Type v CRISPR-Cas Cpf1 endonuclease employs a unique mechanism for crRNA-mediated target DNA recognition. Cell Res. 2016;26:901–13.

Hirano S, Nishimasu H, Ishitani R, Nureki O. Structural Basis for the Altered PAM Specificities of Engineered CRISPR-Cas9. Mol Cell. 2016;61:886–94.

Yamano T, Zetsche B, Ishitani R, Zhang F, Nishimasu H, Nureki O. Structural basis for the canonical and non-canonical PAM Recognition by CRISPR-Cpf1. Mol Cell. 2017;67:633-645.e3.

Tu M, Lin L, Cheng Y, He X, Sun H, Xie H, et al. A new lease of life’: FnCpf1 possesses DNA cleavage activity for genome editing in human cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:11295–304.

Fonfara I, Richter H, BratoviÄ M, le Rhun A, Charpentier E. The CRISPR-associated DNA-cleaving enzyme Cpf1 also processes precursor CRISPR RNA. Nature. 2016;532:517–21.

Zetsche B, Heidenreich M, Mohanraju P, Fedorova I, Kneppers J, Degennaro EM, et al. Multiplex gene editing by CRISPR-Cpf1 using a single crRNA array. Nat Biotechnol 2017. p. 31–4. https://www.nature.com/articles/nbt.3737

Strohkendl I, Saifuddin FA, Rybarski JR, Finkelstein IJ, Russell R. Kinetic Basis for DNA Target Specificity of CRISPR-Cas12a. Mol Cell. 2018;71:816-824.e3.

Kim HJ, Oh SY, Lee SJ. Single-base genome editing in Corynebacterium glutamicum with the help of negative selection by target-mismatched CRISPR/Cpf1. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2020;30:1583–91. https://doi.org/10.4014/jmb.2006.06036.

Li B, Liang S, Alariqi M, Wang F, Wang G, Wang Q, et al. The application of temperature sensitivity CRISPR/LbCpf1 (LbCas12a) mediated genome editing in allotetraploid cotton (G. hirsutum) and creation of nontransgenic, gossypol-free cotton. Plant Biotechnol J. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1111/pbi.13470.

Swarts DC. Making the cut(s): How Cas12a cleaves target and non-target DNA. Biochemical Society Transactions. Portland Press Ltd; 2019. p. 1499–510. /biochemsoctrans/article/47/5/1499/220695/Making-the-cut-s-how-Cas12a-cleaves-target-and-non

Singh D, Mallon J, Poddar A, Wang Y, Tippana R, Yang O, et al. Real-time observation of DNA target interrogation and product release by the RNA-guided endonuclease CRISPR Cpf1 (Cas12a). PNAS. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1718686115.

Chen JS, Ma E, Harrington LB, da Costa M, Tian X, Palefsky JM, et al. CRISPR-Cas12a target binding unleashes indiscriminate single-stranded DNase activity. Science. 2018;360:436–9.

Nguyen LT, Smith BM, Jain PK. Enhancement of trans-cleavage activity of Cas12a with engineered crRNA enables amplified nucleic acid detection. Nat Commun. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-18615-1.

Swarts DC, Jinek M. Mechanistic Insights into the cis- and trans-Acting DNase Activities of Cas12a. Mol Cell. 2019;73:589–600. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2018.11.021.

Li SY, Cheng QX, Liu JK, Nie XQ, Zhao GP, Wang J. CRISPR-Cas12a has both cis- and trans-cleavage activities on single-stranded DNA. Cell Res. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41422-018-.

Wang X, Chen X, Chu C, Deng Y, Yang M, Ji Z, et al. Four-stage signal amplification for trace ATP detection using allosteric probe-conjugated strand displacement and CRISPR/Cpf1 trans-cleavage (ASD-Cpf1). Sens Actuat Chem. 2020;323:128653.

Zhao N, Li L, Luo G, Xie S, Lin Y, Han S, et al. Multiplex gene editing and large DNA fragment deletion by the CRISPR/Cpf1-RecE/T system in Corynebacterium glutamicum. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2020;47:599–608. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10295-020-02304-5.

Hao W, Suo F, Lin Q, Chen Q, Zhou L, Liu Z, et al. Design and construction of portable CRISPR-Cpf1-mediated genome editing in bacillus subtilis 168 oriented toward multiple utilities. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2020;8:524676. https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2020.524676/full.

Hochstrasser ML, Doudna JA. Cutting it close: CRISPR-associated endoribonuclease structure and function. Trends Biochem Sci. 2015;8:58–66.

Smith CW, Nandu N, Kachwala MJ, Chen YS, Uyar TB, Yigit MV. Probing CRISPR-Cas12a nuclease activity using double-stranded DNA-templated fluorescent substrates. Biochemistry. 2020;59:1474–81.

Zetsche B, Gootenberg JS, Abudayyeh OO, Slaymaker IM, Makarova KS, Essletzbichler P, et al. Cpf1 Is a Single RNA-Guided Endonuclease of a Class 2 CRISPR-Cas System. Cell Cell Press. 2015;163:759–71.

Kim D, Kim J, Hur JK, Been KW, Yoon SH, Kim JS. Genome-wide analysis reveals specificities of Cpf1 endonucleases in human cells. Nature Biotechnology Nature Publishing Group. 2016;34:863–8.

Moreno-Mateos MA, Fernandez JP, Rouet R, Vejnar CE, Lane MA, Mis E, et al. CRISPR-Cpf1 mediates efficient homology-directed repair and temperature-controlled genome editing. Nat Commun. 2017;8:e20.

Kim HK, Song M, Lee J, Menon AV, Jung S, Kang YM, et al. In vivo high-throughput profiling of CRISPR-Cpf1 activity. Nat Methods. 2017;14:153–9.

Verwaal R, Buiting-Wiessenhaan N, Dalhuijsen S, Roubos JA. CRISPR/Cpf1 enables fast and simple genome editing of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. 2017.

Dai Y, Somoza RA, Wang L, Welter JF, Li Y, Caplan AI, et al. Exploring the Trans-Cleavage Activity of CRISPR-Cas12a (cpf1) for the development of a universal electrochemical biosensor. Angewandte Chemie Int Ed. 2019;58:17399–405. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201910772.

Zhang M, Ye J, He J, Zhang F, Ping J, Qian C, et al. Visual detection for nucleic acid-based techniques as potential on-site detection methods: A review. Anal Chimica Acta. 2020;8:1–15.

Gallego C, Gonçalves MAFV, Wijnholds J. Novel therapeutic approaches for the treatment of retinal degenerative diseases: focus on CRISPR/Cas-Based Gene Editing. Front Neurosci. 2020;9:89.

Gootenberg JS, Abudayyeh OO, Kellner MJ, Joung J, Collins JJ, Zhang F. Multiplexed and portable nucleic acid detection platform with Cas13, Cas12a, and Csm6. 2018. http://science.sciencemag.org/

Bonini A, Poma N, Vivaldi F, Kirchhain A, Salvo P, Bottai D, et al. Advances in biosensing: The CRISPR/Cas system as a new powerful tool for the detection of nucleic acids. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2021;192: 113645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpba.2020.113645.

de Puig H, Bosch I, Collins JJ, Gehrke L. Point-of-care devices to detect zika and other emerging viruses. Ann Rev Biomed Eng. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-bioeng-060418-.

Balan V, Wang J. The CRISPR System and Cancer Immunotherapy Biomarkers. Methods Mol Biol 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-9773-2_14

Chertow DS. SCIENCE sciencemag.org. 2018; http://stm.sciencemag.org/content/scitransmed/8/360/360ra134.full

Redman M, King A, Watson C, King D. What is CRISPR/Cas9? Arch Dis Childhood. 2016;101:213–5.

Yu W, Wu Z. Ocular delivery of CRISPR/Cas genome editing components for treatment of eye diseases. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2020;89:9.

Xiang X, Qian K, Zhang Z, Lin F, Xie Y, Liu Y, et al. CRISPR-cas systems based molecular diagnostic tool for infectious diseases and emerging 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pneumonia. J Drug Targeting. 2020;3:727–31.

Ji T, Liu Z, Wang GQ, Guo X, Akbar S, Lai C, et al. Detection of COVID-19: A review of the current literature and future perspectives. Biosens Bioelectron. 2020;166:e230.

Kostyusheva A, Brezgin S, Babin Y, Vasil’eva I, Kostyushev D, Chulanov V. CRISPR-Cas Systems for Diagnosing Infectious Diseases. 2020. www.preprints.org

Li J, Yang S, Zuo C, Dai L, Guo Y, Xie G. Applying CRISPR-Cas12a as a signal amplifier to construct biosensors for non-DNA targets in ultralow concentrations. ACS Sensors. 2020;5:970–7. https://doi.org/10.1021/acssensors.9b02305.

Zhu C, Liu C, Qiu X, Xie S, Li W, Zhu L, et al. Novel nucleic acid detection strategies based on CRISPR-Cas systems: From construction to application. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2020;117:2279–94. https://doi.org/10.1002/bit.27334.

van Dongen JE, Berendsen JTW, Steenbergen RDM, Wolthuis RMF, Eijkel JCT, Segerink LI. Point-of-care CRISPR/Cas nucleic acid detection: Recent advances, challenges and opportunities. Biosens Bioelectron. 2020;166:112445.

Wang M, Zhang R, Li J. CRISPR/cas systems redefine nucleic acid detection: Principles and methods. Biosens Bioelectron. 2020. p. 112430.

Wang X, Shang X, Huang X. Next-generation pathogen diagnosis with CRISPR/ Cas-based detection methods Next-generation pathogen diagnosis with CRISPR/Cas-based detection methods. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1080/22221751.2020.1793689.

Batista AC, Pacheco LGC. Detecting pathogens with Zinc-Finger, TALE and CRISPR- based programmable nucleic acid binding proteins. J Microbiol Methods. 2018;9:98–104.

Chaijarasphong T, Thammachai T, Itsathitphaisarn O, Sritunyalucksana K, Suebsing R. Potential application of CRISPR-Cas12a fluorescence assay coupled with rapid nucleic acid amplification for detection of white spot syndrome virus in shrimp. Aquaculture. 2019;512:734340.

Chen Y, Shi Y, Chen Y, Yang Z, Wu H, Zhou Z, et al. Contamination-free visual detection of SARS-CoV-2 with CRISPR/Cas12a: A promising method in the point-of-care detection. Science. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bios.2020.112642.

Xu H, Zhang X, Cai Z, Dong X, Chen G, Li Z, et al. An Isothermal Method for Sensitive Detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Complex Using Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats/Cas12a Cis and Trans Cleavage. J Mol Diagn. 2020;22:1020–9.

Wang Q, Alariqi M, Wang F, Li B, Ding X, Rui H, et al. The application of a heat-inducible CRISPR/Cas12b (C2c1) genome editing system in tetraploid cotton ( G hirsutum ) plants. Plant Biotechnol J. 2020;18:2436–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/pbi.13417.

Merker L, Schindele P, Huang T, Wolter F, Puchta H. Enhancing in planta gene targeting efficiencies in Arabidopsis using temperature-tolerant CRISPR/ Lb Cas12a. Plant Biotechnol J. 2020;18:2382–4. https://doi.org/10.1111/pbi.13426.

Dong Z, Qin Q, Hu Z, Zhang X, Miao J, Huang L, et al. CRISPR/Cas12a Mediated Genome Editing Enhances Bombyx mori Resistance to BmNPV. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2020;8:841. https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2020.00841/full.

Kellner MJ, Koob JG, Gootenberg JS, Abudayyeh OO, Zhang F. SHERLOCK: nucleic acid detection with CRISPR nucleases. Nature Protocols Nature Publishing Group. 2019;14:2986–3012.

Lee Y, Choi J, Han HK, Park S, Park SY, Park C, et al. Fabrication of ultrasensitive electrochemical biosensor for dengue fever viral RNA Based on CRISPR/Cpf1 reaction. Sens Actuat B: Chem. 2021;326:128677.

Zhang G, Zhang L, Tong J, Zhao X, Ren J. CRISPR-Cas12a enhanced rolling circle amplification method for ultrasensitive miRNA detection. Microchem J. 2020;158:89.

Palumbo CM, Gutierrez-Bujari JM, O’Geen H, Segal DJ, Beal PA. Versatile 3′ Functionalization of CRISPR Single Guide RNA. ChemBioChem. 2020;21:1633–40. https://doi.org/10.1002/cbic.201900736.

Jiang T, Henderson JM, Coote K, Cheng Y, Valley HC, Zhang XO, et al. Chemical modifications of adenine base editor mRNA and guide RNA expand its application scope. Nat Commun. 2020;11:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-15892-8.

Scott T, Soemardy C, Morris KV. Development of a facile approach for generating chemically modified CRISPR/Cas9 RNA. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2020;19:1176–85.

Zhang D, Yan Y, Que H, Yang T, Cheng X, Ding S, et al. CRISPR/Cas12a-Mediated Interfacial Cleaving of Hairpin DNA Reporter for Electrochemical Nucleic Acid Sensing. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1021/acssensors.9b02461.

Xu W, Jin T, Dai Y, Liu CC. Surpassing the detection limit and accuracy of the electrochemical DNA sensor through the application of CRISPR Cas systems. Biosens Bioelectron. 2020;155:112100.

Zhang D, Yan Y, Que H, Yang T, Cheng X, Ding S, et al. CRISPR/Cas12a-Mediated Interfacial Cleaving of Hairpin DNA Reporter for Electrochemical Nucleic Acid Sensing. ACS Sens. 2020;5:557–62. https://doi.org/10.1021/acssensors.9b02461.

Ramanaviciene A, German N, Kausaite-Minkstimiene A, Voronovic J, Kirlyte J, Ramanavicius A. Comparative study of surface plasmon resonance, electrochemical and electroassisted chemiluminescence methods based immunosensor for the determination of antibodies against human growth hormone. Biosens Bioelectron. 2012;36:48–55.

Ramanavicius A, Genys P, Ramanaviciene A. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy based evaluation of 1,10-phenanthroline-5,6-dione and glucose oxidase modified graphite electrode. Electrochim Acta. 2014;146:659–65.

Valiuniene A, Petroniene J, Morkvenaite-Vilkonciene I, Popkirov G, Ramanaviciene A, Ramanavicius A. Redox-probe-free scanning electrochemical microscopy combined with fast Fourier transform electrochemical impedance spectroscopy. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2019;21:9831–6.

Wang X, Zhong M, Liu Y, Ma P, Dang L, Meng Q, et al. Rapid and sensitive detection of COVID-19 using CRISPR/Cas12a-based detection with naked eye readout, CRISPR/Cas12a-NER. Sci Bull. 2020;65:1436–9.

Ma P, Meng Q, Sun B, Zhao B, Dang L, Zhong M, et al. MeCas12a, a Highly Sensitive and Specific System for COVID-19 Detection. Adv Sci. 2020;7:7536916.

Song Q, Sun X, Dai Z, Gao Y, Gong X, Zhou B, et al. Point-of-care testing detection methods for COVID-19. Lab Chip. 2021;21:1634–60.

Jolany Vangah S, Katalani C, Booneh HA, Hajizade A, Sijercic A, Ahmadian G. CRISPR-based diagnosis of infectious and noninfectious diseases. Biol Proc Online. 2020;8:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12575-020-00135-3.

Islam KU, Iqbal J. An Update on Molecular Diagnostics for COVID-19. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. 2020. p. 694. www.frontiersin.org

English MA, Soenksen LR, Gayet R v, de Puig H, Angenent-Mari NM, Mao AS, et al. Programmable CRISPR-responsive smart materials. http://science.sciencemag.org/

Hajian R, Balderston S, Tran T, deBoer T, Etienne J, Sandhu M, et al. Detection of unamplified target genes via CRISPR–Cas9 immobilized on a graphene field-effect transistor. Nat Biomed Eng. 2019;3:427–37.

Dai Y, Wu Y, Liu G, Gooding JJ. CRISPR mediated biosensing toward understanding cellular biology and point-of-care diagnosis. Angew Chem. 2020;132:20938–50. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.202005398.

Acknowledgements

Schematic illustrations and images were created using https://BioRender.com.

Funding

This research has received funding according to Agreement No S-LLT-21-3 with Research Council of Lithuania (LMTLT). BioRender.com was used to create the schematic illustrations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JD, USB, and AR contributed equally to the review of literature, organization, and writing of this review article. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Dronina, J., Samukaite-Bubniene, U. & Ramanavicius, A. Towards application of CRISPR-Cas12a in the design of modern viral DNA detection tools (Review). J Nanobiotechnol 20, 41 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12951-022-01246-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12951-022-01246-7